Chapter Eight-Six: The CSA Presidential Election of 1921

A photograph of excited Arkansas Democratic delegates, hoping to finally reclaim the Executive Branch

For the 21 years, the Liberty Party had managed to hold onto the executive branch of the Confederate government. Weathering the collapse of their coalition with the moderate Democrats, and winning two elections that were predicted to be Democratic years, it seemed that they were charmed in presidential elections. By 1921, however, they were a thoroughly weakened and exhausted party. By holding power for so long, they had managed to get much their agenda passed, and were struggling to develop new initiatives for their party to campaign on. Furthermore, they were finding it difficult to find a new face to rally behind. Until the 1915 election, every one of their presidential candidates had served as a general in the American Civil War, which by now was a bygone era. Without their traditional and preferred candidate to rally behind, they turned to the next best thing, a hero of another war, namely the Mexican Revolution. Secretary of War George H. Thomas Jr., however, declined to be a candidate just as he had done in 1915. With Underwood ineligible, and both Vice-President Duncan and Secretary of State Culberson unenthusiastic about running, the leaders of the current administration were out as well. Thus, the convention descended into madness.

Woodrow Wilson addressing a crowd at the convention. Despite being humiliated during the Cleburne administration, Wilson hoped his career would rebound, and attempted to bring this about at the 1921 Liberty National Convention

As it opened, the lack of a prominent figure seeking the nomination left a vacuum that would be filled by a plethora of minor candidates. Among them were first term senator Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas, former Vice-President and current Georgia senator M. Hoke Smith, Ambassador to the United States John W. Smith, Major General Duncan Hood (who had the endorsement of Thomas Jr.), Postmaster General Milford W. Howard, and Arizona Senator Marcus A. Smith. A minor, and largely ignored, candidate took the form of former Secretary of the Navy Woodrow Wilson. Currently out of favor with most of the party due to his conniving against Cleburne, he was unsurprised when his candidacy failed to gain much steam. Realizing that the only way he could regain power was to be in favor with the eventual nominee, Wilson began probing the bases of his rival candidates to attempt to predict who would receive the nomination. Meanwhile, the first ballot took place, with M. Hoke Smith leading, as he was the most favored by the party establishment. The rest of the candidates filled out the delegate count without any notable surprises. Knowing Smith was too close to the administration he tried to overthrow to be willing to take his support, Wilson would instead extend his backing to the runner-up, Ambassador John W. Smith. And as the ballots continued, and M. Hoke Smith began slowly bleeding support, many others within the convention came to the same result. Seeing the tide finally moving towards a nominee, President Underwood would endorse John W. Smith's candidacy. Following some politicking by Wilson within the Virginia delegation, Smith finally received enough delegates on the 34th ballot. By nominating a dark horse and relatively unknown candidate, the Liberty Party realized they would have trouble with fundraising for the campaign. This, alongside with wanting to solidify the base of the Southwestern states, can explain the selection of Chihuahua Governor Enrique "Henry Clay" Creel as Smith's running-mate, as he had a vast personal fortune from his business endeavors. Overall, many of the average party members found the ticket uninspiring, unexciting, and bland.

John Smith and Enrique Creel

The Democratic Nominating Convention, by comparison, was highly energized. Three promising candidates were presented in the form of Speaker of the House Carter Class of Virginia, South Carolina Senator Coleman L. Blease, and former North Carolina Senator Furnifold Simmons. Each was able to rally considerable support for their candidacies despite being from neighboring states, and each stood out from one another. Glass was seen as a moderate who wouldn't shake up the current, and quite prosperous, establishment and instead enact Democratic versions of the current programs. Blease, meanwhile, was the radical, calling for the repeal of the abolition amendment, the removal of Confederate Army troopers from African-American communities to allow the white vigilantes to once again become the rule of law, and the stepping back from relations with the United States, including possibly even annulling the greatest achievement of the Underwood administration, the Triple Alliance. Simmons, finally, represented a mixture of Glass and Blease. While supporting Glass' positions on adapting many of the current government policies to a Democratic version and maintaining the Triple Alliance, he also supported Blease's points on racial issues, including the amendment and army encampments. His effective hedging between the two camps provided Simmons with the early lead in the convention, but the three way race ensured no candidate secured the necessary delegate count. Hoping to undermine the Glass campaign and break the deadlock, Simmons would reach out to General-in-Chief of the Confederate States Thomas J. Jackson II, son of President Jackson. From the sidelines, Jackson II had been quieting watching the convention and pondering if he should announce himself as a candidate. When Simmons reached out to him, that was the last prodding he required. Jackson's entry shocked the convention floor. Further surprise was brought about when Glass dropped out and endorsed Jackson, which led many to suspect either he had been the one to convince him to enter the race, or that he had swiftly made a deal with the general. Ultimately, the latter was true, having been promised the State Department. Glass' delegates, combined with those he drew from Blease and Simmons, gave Jackson the support he needed for the nomination. Once nominated for the presidency, Jackson endorsed Simmons to be his running-mate to acknowledge the role he had played in bringing him into the convention. The convention quickly nominated him on the first ballot. Thus, the Democrats finally had their war hero, and they were certain of victory come November.

Thomas Jackson II and Furnifold Simmons

From the start, all signs seemed to point to a landslide Democratic victory. Even the candidates of the Liberty Party acknowledged this. Smith would rarely leave his home throughout the campaign, claiming he preferred front-porch addresses, but privately saying that the race wasn't even worth the train fares. Similarly, Creel would hold back much of the funding that he had been nominated for, and even at one point considering dropping himself from the ticket. Meanwhile, Jackson and his surrogates crisscrossed the nation, magnifying his achievements in the Mexican Revolution and appealing to the common man. Many newspapers of the day would point out that Jackson II had more in common with President Andrew Jackson than his father President Stonewall Jackson. When questioned why his political stances varied so widely from his father's, Jackson II would cite the time he had spent in the field. Unlike his father, he had risen through the ranks without a start at general, and he had fostered much closer relations with the common soldier. He also stated that the times had changed from the days of his father, and the best policies for the nation had changed with it. Ultimately, his campaign to connect with the common man succeed, and it seemed that in every state, even traditionally Liberty ones, banners of "Jackson for the Confederacy" or "Like Father, Like Son" were affixed in public places. When election night came, Jackson eagerly sat by the telephone with his friends and close advisers. Smith, meanwhile, slept through it in his mansion.

A photograph of Smith's mansion, where the few campaign rallies he did host were held

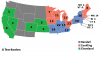

When the results came in, they were the crushing landslide everyone had expected. Jackson had stomped Smith, winning 130 electoral votes compared to 32. Jackson had carried South Carolina, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Virginia, Alabama, Sonora, Chihuahua, and Georgia. Smith had only won Maryland, Tennessee, Arizona, Baja California, and Verdigris. Jackson's crushing victory has often been attributed to his ability to not only rally Democrats out in droves, but also due to his appeal to traditional Liberty states. The most prominent examples of this were Sonora and Chihuahua. Although both were heavily Liberty, returning a fully Liberty congressional slate, they had gone, albeit narrowly for Jackson. This was likely to due to their memory of him being their defender during the Mexican Revolution, as well as the appeals to the common folk who populated the state. With an expanded majority in the House and a Senate flipped Democratic, Jackson and the Democratic Party seemed to have the mandate of the people to enact their policies.

/Russian_Troops-1917-57bf8eb35f9b5855e5525212.jpg)

/Russian_Troops-1917-57bf8eb35f9b5855e5525212.jpg)