Epilogue

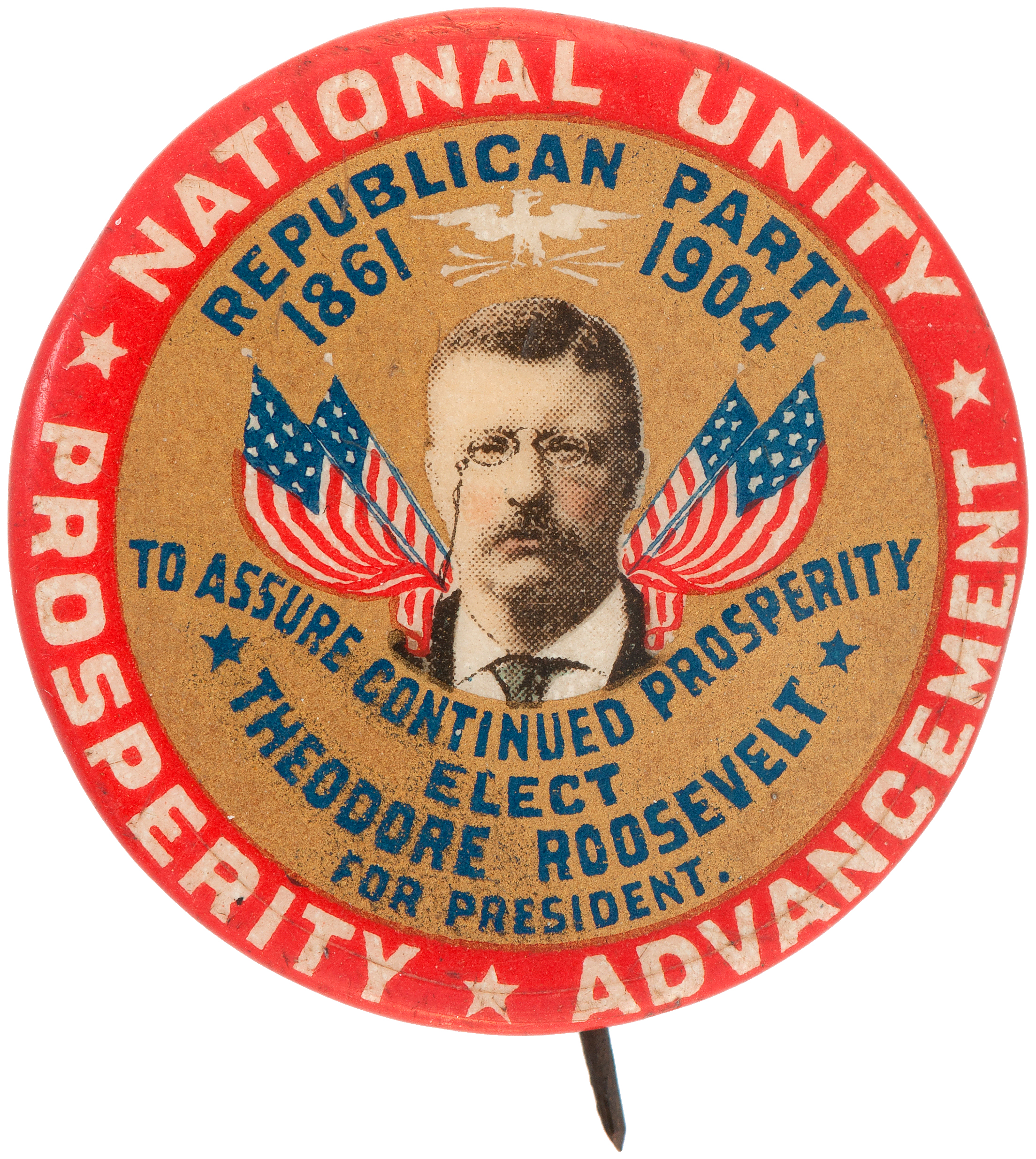

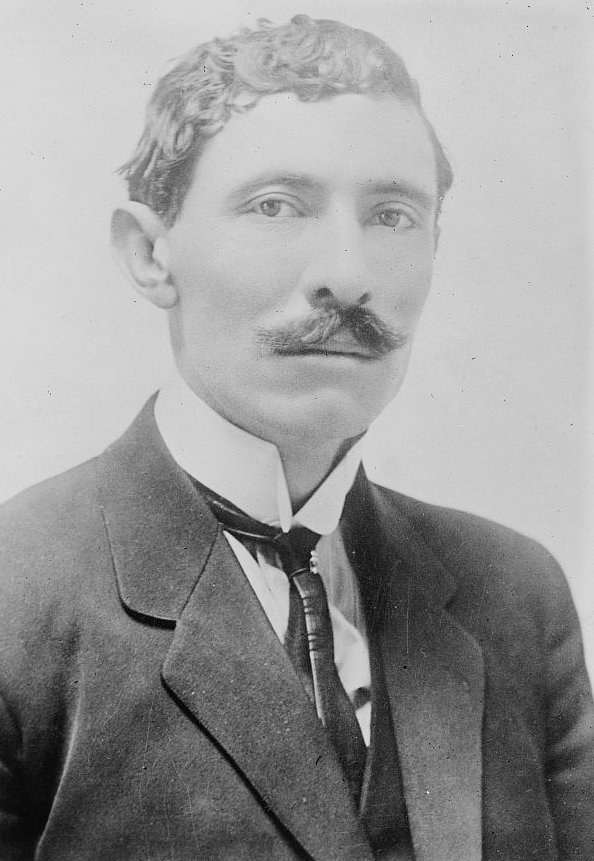

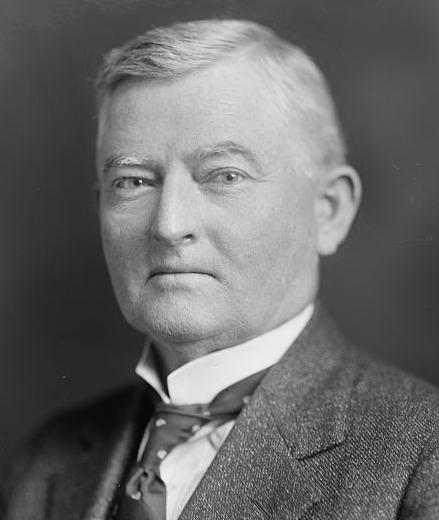

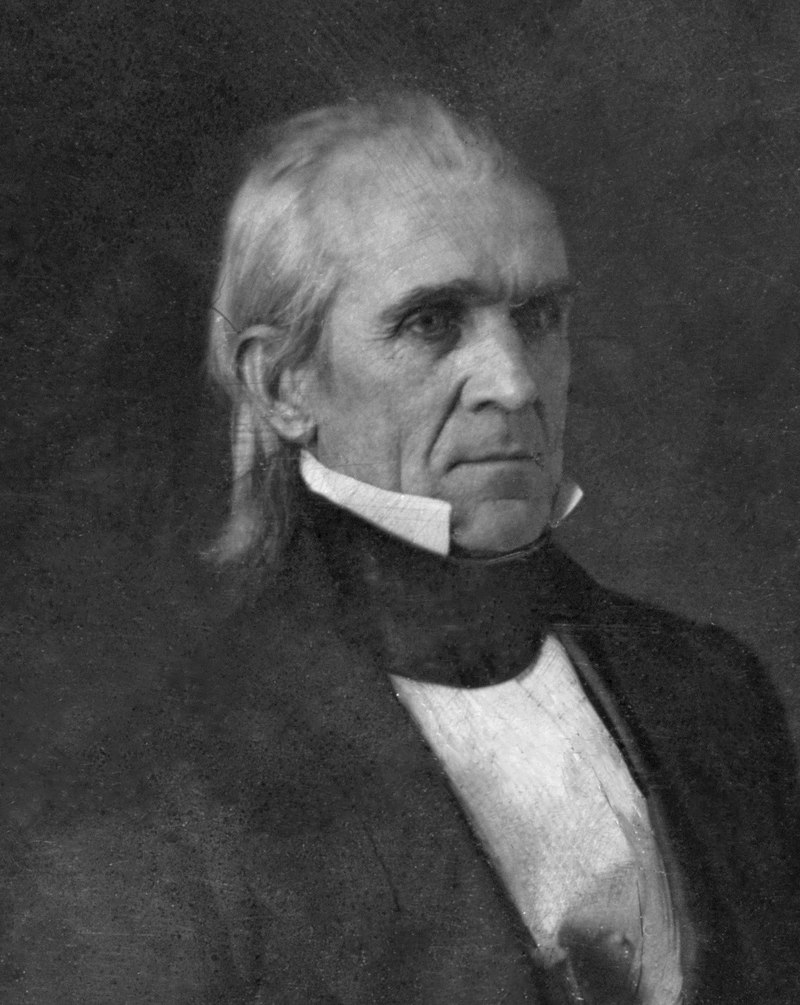

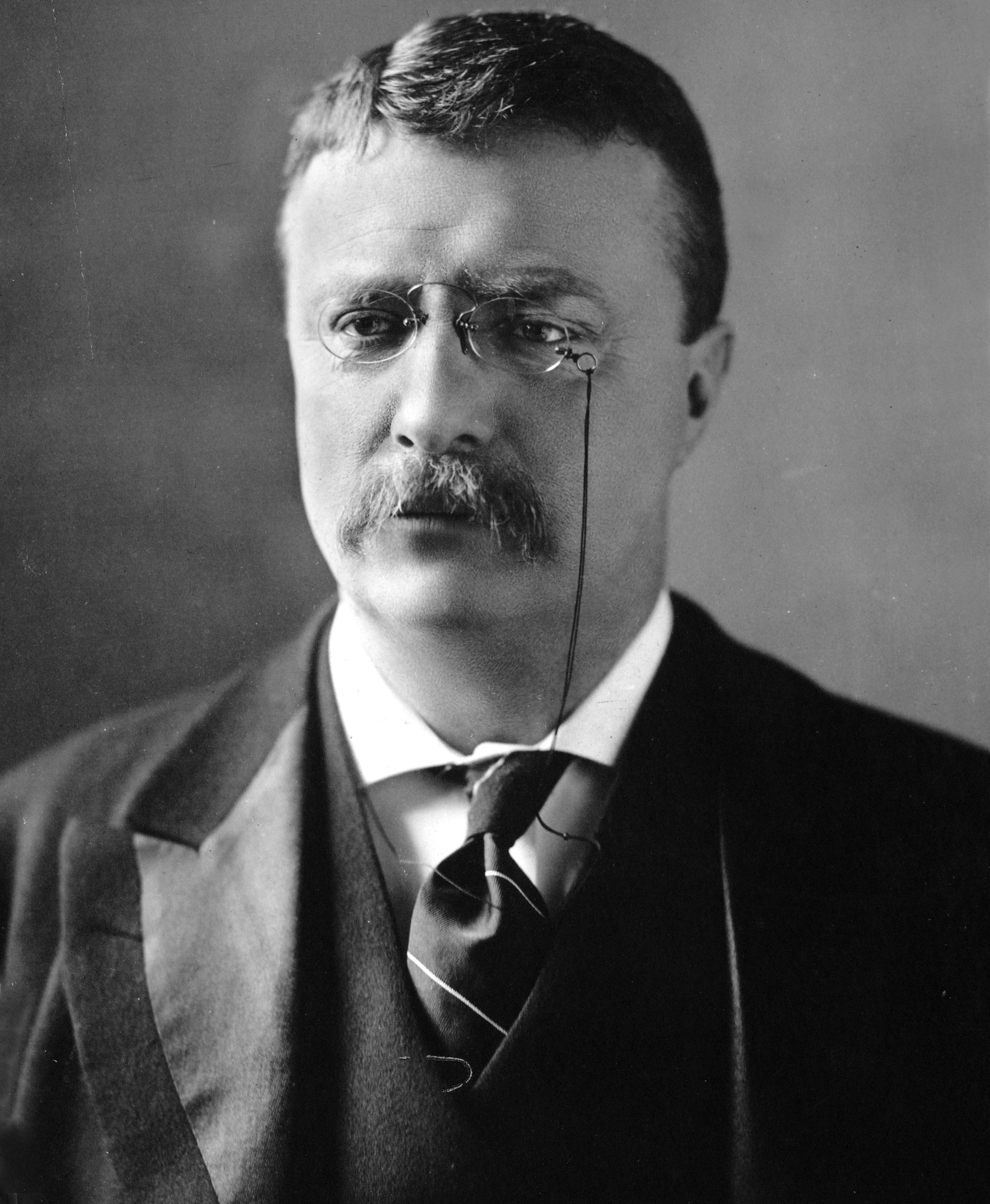

Theodore Roosevelt: After leaving office in 1909, Roosevelt still remained a force in U.S. politics. He was regularly consulted by his successor and friend, Henry C. Lodge, as well as Lodge’s successor, Charles E. Hughes. Ultimately, Roosevelt would live on until 1921, with him going down in history as the greatest American president since Garfield, and rivaling even the Founders as the greatest American in history.

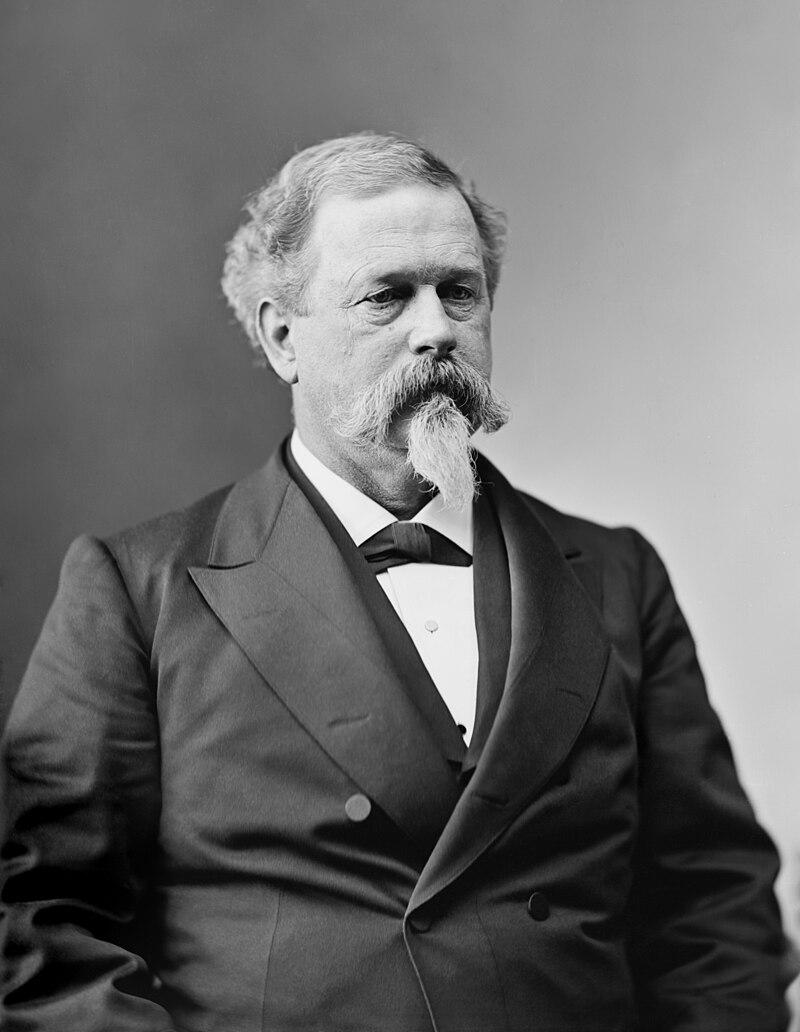

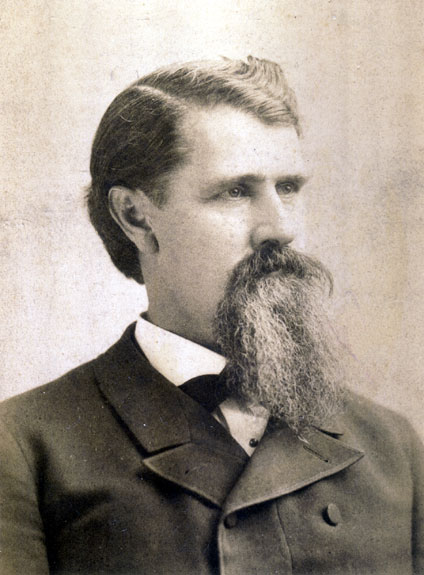

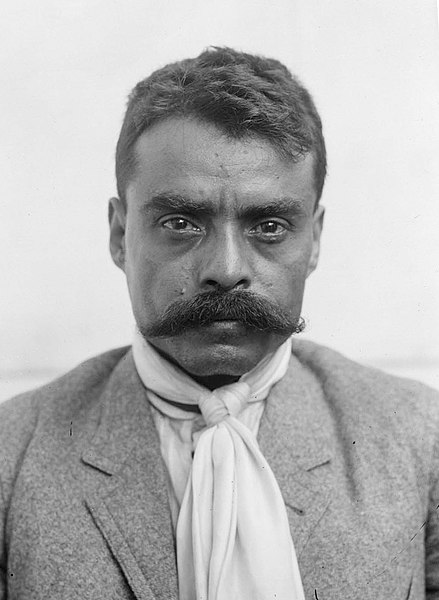

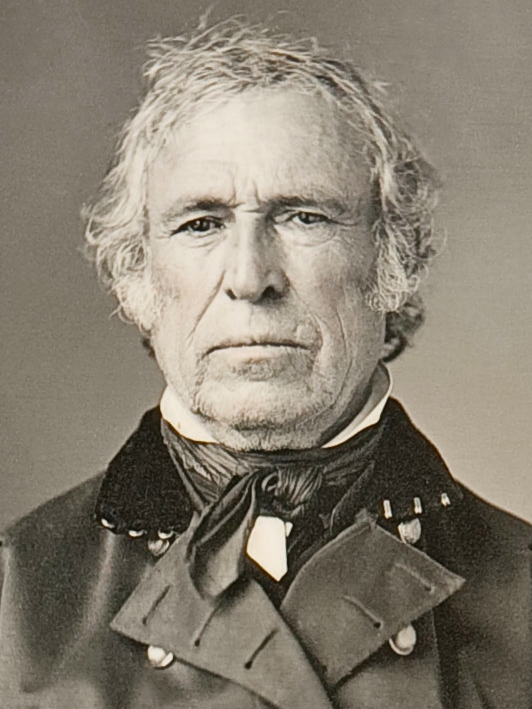

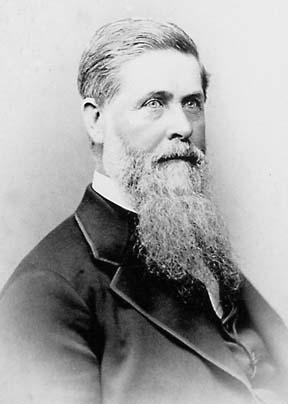

Simon B. Buckner: It was in Buckner’s term that the last five CSA states with slavery sucessfully approved gradual emancipation plans. With the closure of his term in office, Buckner would return to his home state of Arizona. From there, he would live out the rest of his days in peace, eventually passing away in 1914.

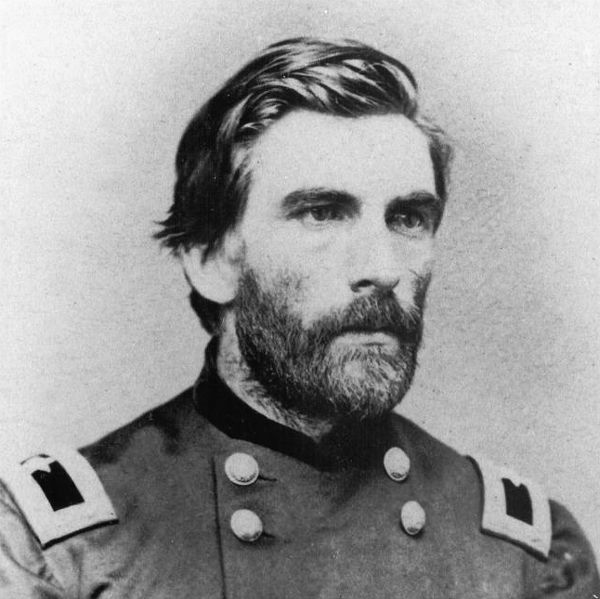

George H. Thomas Jr: Thomas would continue his service in the army until 1914, resigning at the rank of full General. He would return to the public eye, however, by becoming Secretary of War under President Underwood. In this position, he would support Underwood in his efforts to quash the small pockets of slavery remaining in the country even after the passage of the abolition amendment, even going so far as to send in small detachments of troops to quash riots and hate groups that cropped up in the South as a result of the final emancipation. He would request of President Jackson II to stay on as his Secretary of War to properly finish these goals despite their differing political parties. This request would be denied, with many attributing this as Jackson’s getting his revenge for his plans being rejected during the Mexican Revolution. This would result in those his objectives dying after with his leaving of office and the pulling out of the troops he sent in. To his dying day, Thomas would always regret the lives lost as a result of the pull out, with his last words in 1942 being “How many lives have been lost as a result of me?”

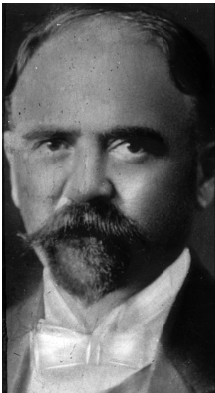

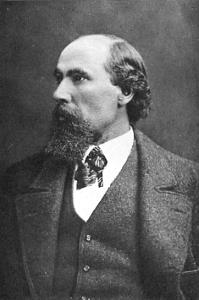

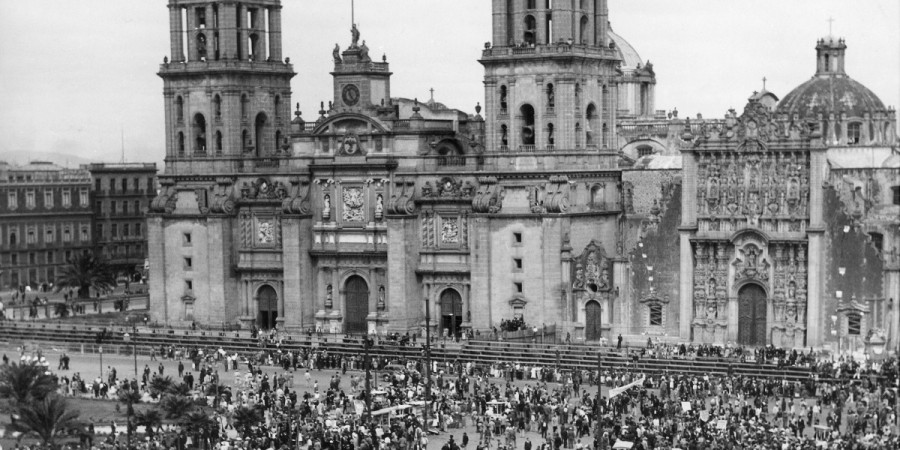

Patrick Cleburne: Buckner’s Secretary of State would also prove to be his successor to the office of the presidency, with elected with M. Hoke Smith as Vice President. From there, Cleburne would effectively end his political career as well as the moderate Democratic-Liberty Party coalition created by Bate and continued by Buckner with his support of an abolition amendment that put a permanent end to slavery in the CSA, despite all of the states already having finished their gradual emancipation programs by the time of its passage. Although Cleburne would manage to see to the amendment's successful approval, he would be hated in his time for it, and an effort to remove and besmirch him in Confederate memory began. In the modern day, however, he is remembered for what he was, among the greatest of the CSA’s generals from the American Civil War and Confederate-American War, as well as one of their bravest presidents. He was also noted for bringing in the last piece of the CSA's original territory, the Indian Territory, into the Confederacy as the state of Verdigris, a name chosen by a committee consisting of both citizens of the CSA and U.S. in recognition of their growing cooperation, after the Verdigris River which flowed through the state. This decision would come under fire from many of the Native Americans living there, as they had been left out of the process, but Cleburne would sooth their pain with an increase in Native's rights that he had long been planning.

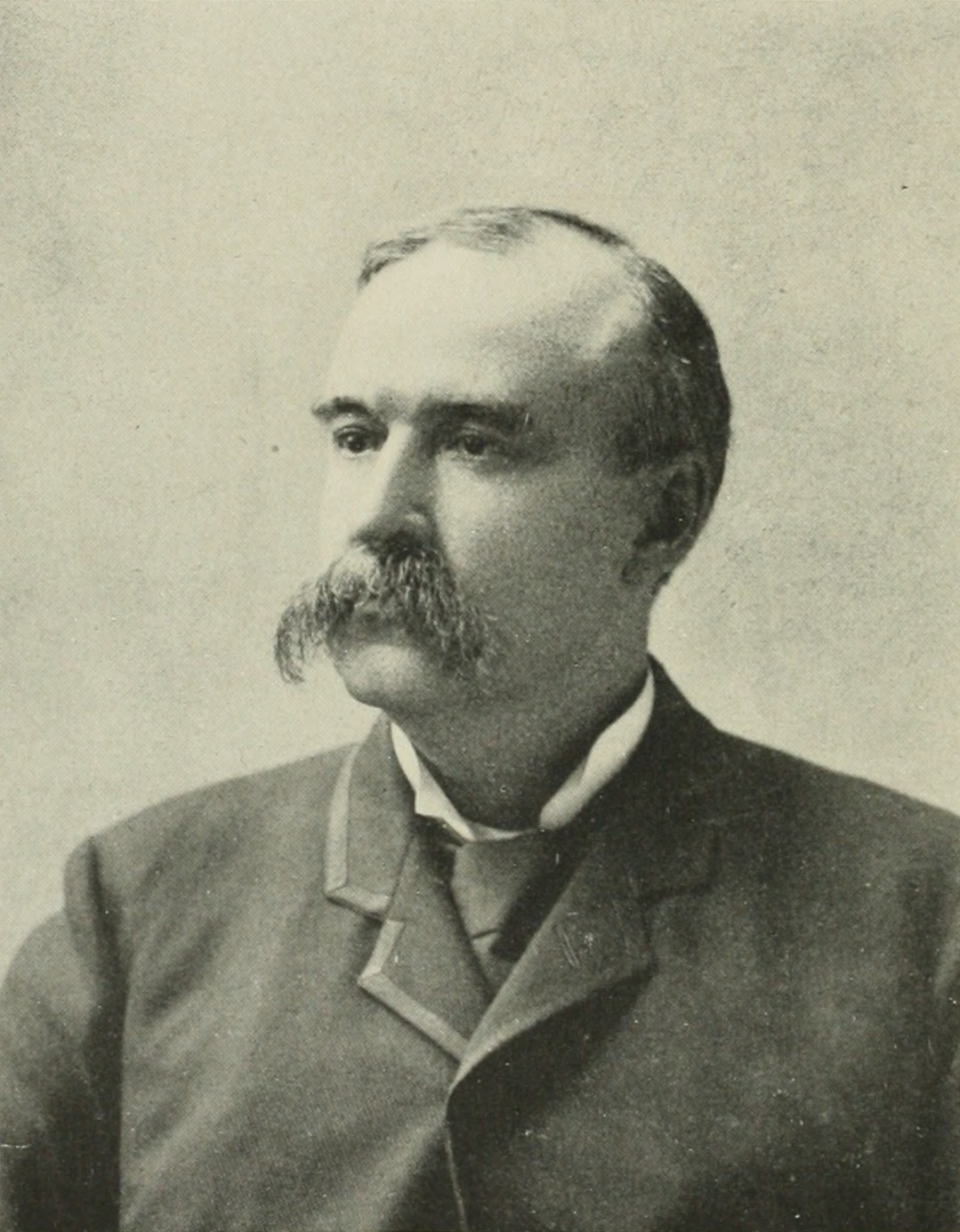

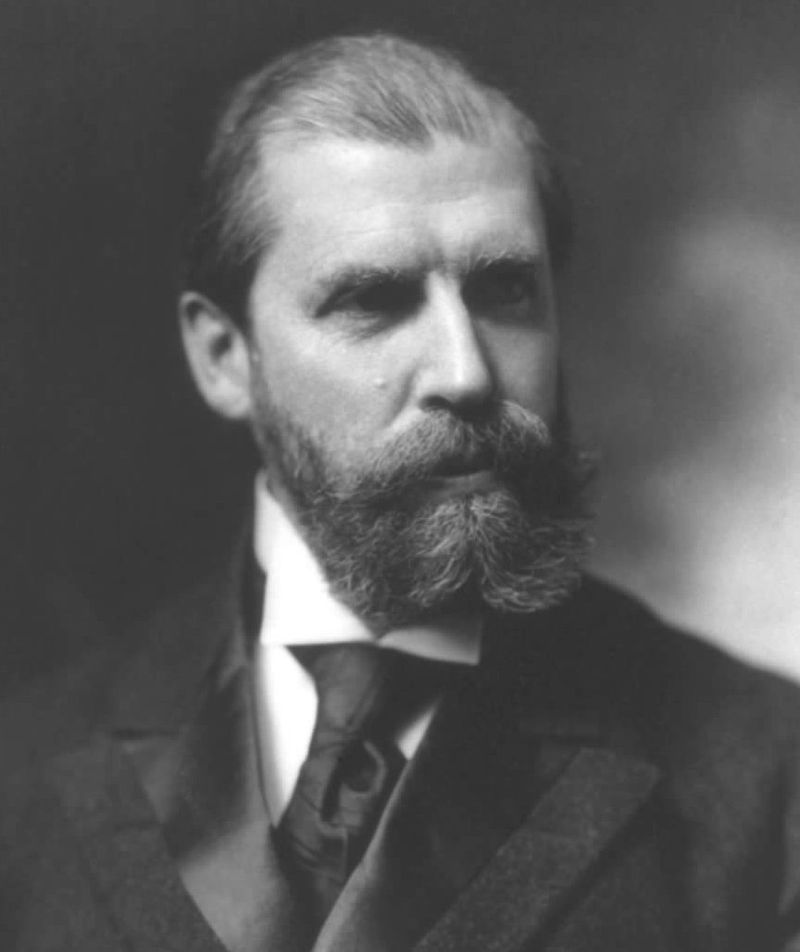

Henry C. Lodge: Roosevelt’s Secretary of State would also reach the executive branch. Lodge would become famous for his desire to enter the Great War on the side of the Allied Powers, although he would never do it in response to public opinion being against it. Still wanting to support them, he would implement a policy of making the U.S. effectively an arms dealer to the Allies, with him eventually and begrudgingly extending this policy to the Central Powers to make clear that America was neutral. Many European historian point to Lodge’s refusal to ignore the voice of the people as the reason for the Allied defeat, if it could be called that, in the Great War, as they speculate that the addition of U.S. forces to the Allied trench lines might have been all that was needed to break through the Central trench lines before French morale finally gave out, bringing the war to a close, although the fall of the allies would occur during the term of his successor.

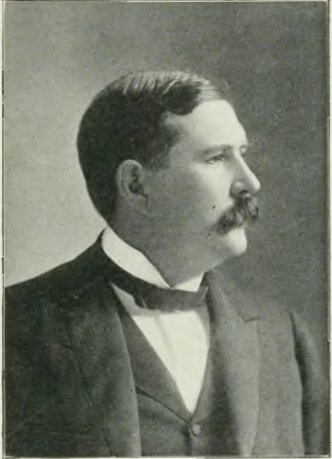

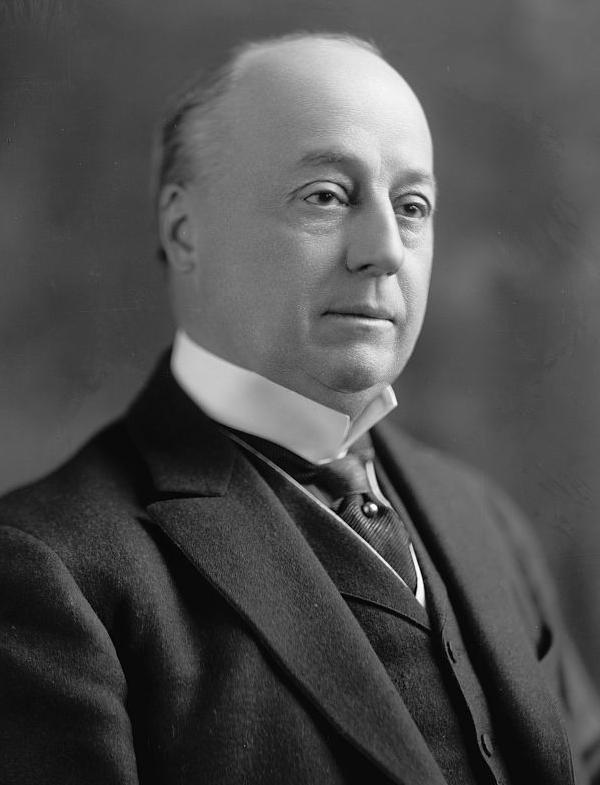

Oscar Underwood: Underwood would ultimately be elected to succeed Cleburne, albeit narrowly, after serving as serving as his Secretary of State. His victory over Claude Kitchin can largely be attributed to the fact that he presented himself as the anti-war candidate, and made Kitchin appear to be a violent warmonger, even though he was as much of a dove as Underwood. While in office, Underwood continued the policy of strengthening U.S.-CSA relations as begun by Roosevelt and Buckner. He and Hughes would sign a defensive pact guaranteeing the support of the other nation in the scenario that one of them is attacked and forced into the war. Underwood’s term in office was focused on internal improvement, as making sure that by 1920 all slavery had been eliminated from the CSA.

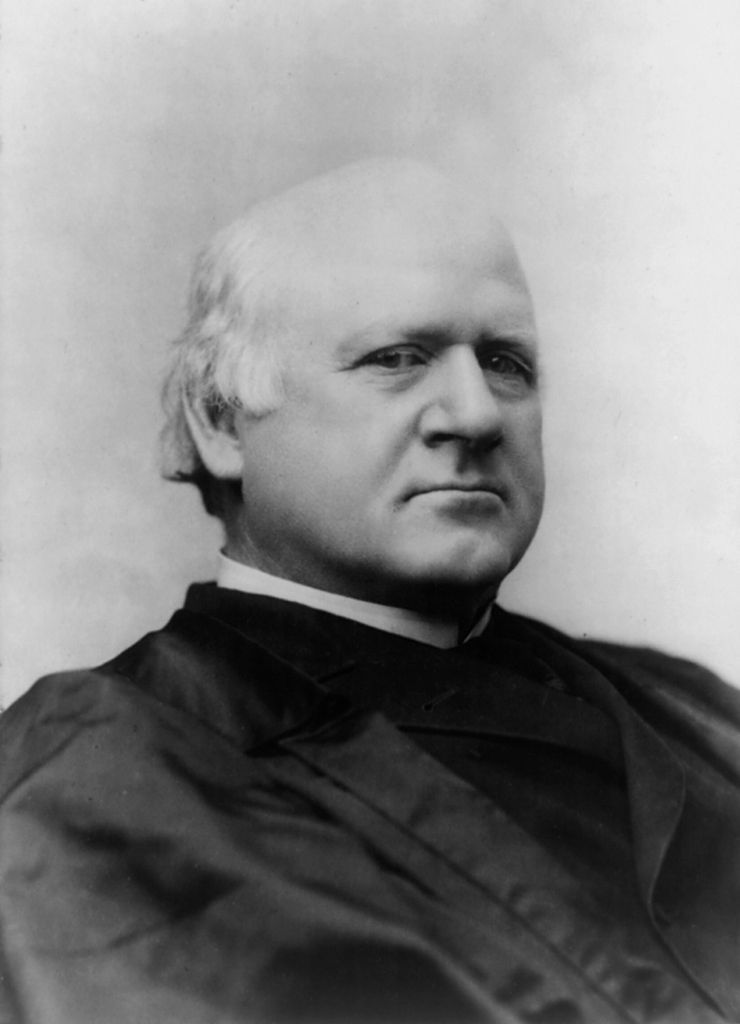

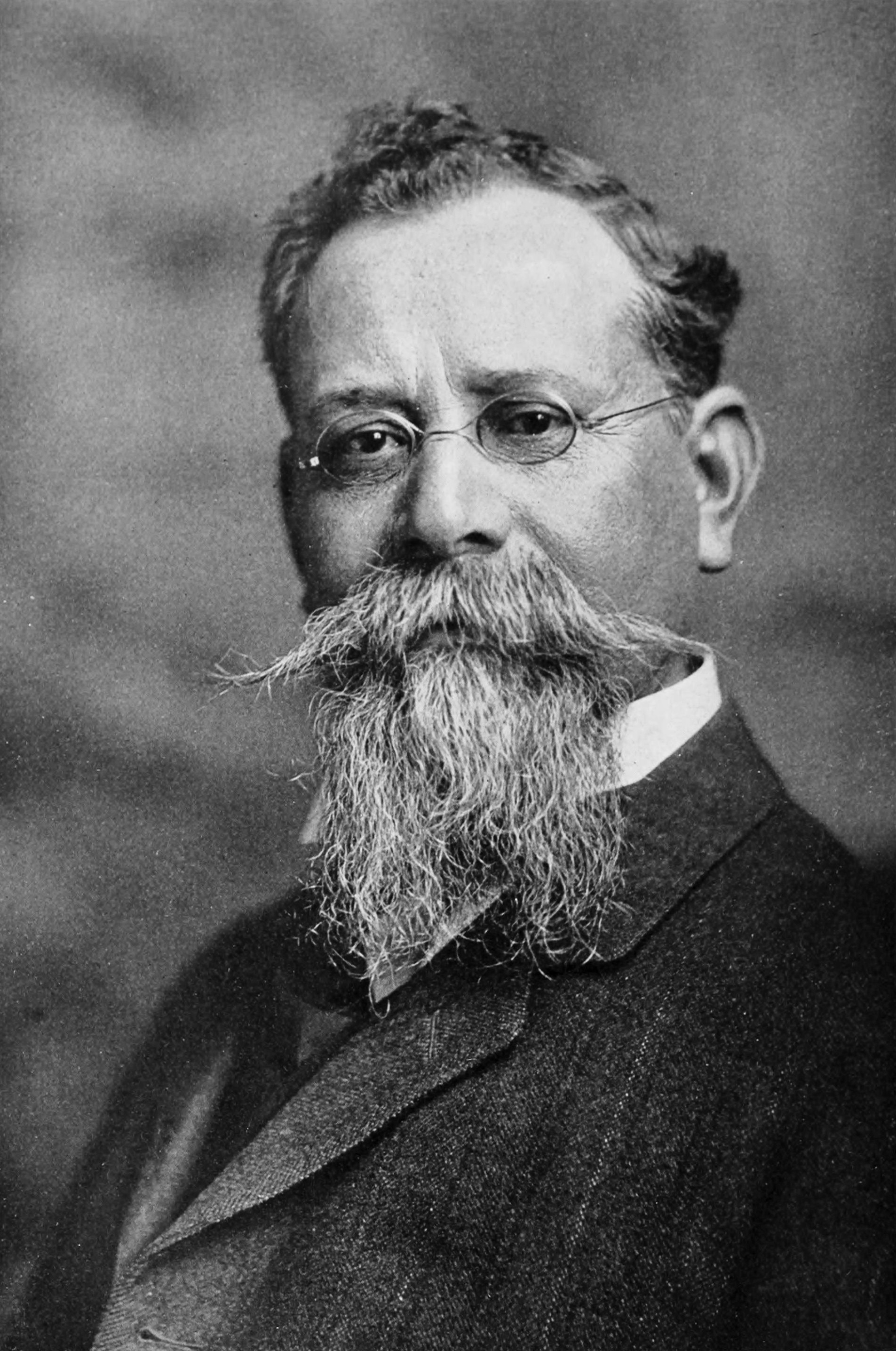

Philander C. Knox: Roosevelt’s Attorney General would go on to become Lodge’s Secretary of State after being considered for the vice-presidency. When the Chief Justiceship of the Supreme Court opened with the death of John M. Harlan, Knox would eagerly seek the position, but faced stiff competition from Ohio Governor William Howard Taft, his chief rival for the nomination. Both men desperately wanted the position, with Lodge ultimately giving it to Knox, whose views better aligned with his. Knox would be succeeded by James E. Watson as Secretary of State. From his new position, Knox would often come into conflict with the more progressive judges of his court, particularly Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, a Roosevelt appointment, and Harlan F. Stone, a Hughes appointee. He was not despised by either of these men, however, and both agreed that Knox ruled by what he thought was the correct way under U.S. law, not by his political alignment. His court’s most famous case would come with Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, in which Henry M. Flagler’s expansive oil monopoly was brought to court for violating the Dolliver Anti-Trust Act. The court’s ruling against Standard Oil would break up the largest monopoly in history with the slam of a gavel. Knox would continue in his role as Chief Justice until his death in 1921.

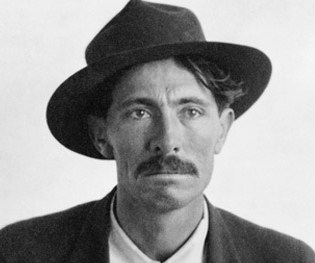

Thomas J. Jackson II: With his gallant service in the Second Mexican War, Jackson had brought himself into the national spotlight. During the Cleburne and Underwood administrations, he stayed out of politics, and kept his political opinions to himself. For the 1921 CSA election, however, he would reveal his Democratic leanings, which he had gained from service under General Forrest. He entered the convention, hoping to bring attention to himself and promote himself as a good candidate for Secretary of War, a position he desired to push for military reform, especially implementing planes and tanks better into the CSA Army. A deadlocked convention, however, would ultimately choose him to be their presidential candidate. His campaign would attack the Liberty Party for ending slavery, as well as for allowing the CSA to remain only a power in the Americas, where entry into the Great War could have made them an international power. Ultimately, Jackson would win the presidency. His term in office would generally be seen as a backslide in terms of civil rights, doing nothing to persecute hate groups attacking the freed slaves in the South. His term would bring about the start of the CSA tank corps, with him placing his former aide-de-camp Colonel George S. Patton Jr. in command of it, and also expanding and innovating the CSA Air Force. When Jackson II left office, he was considered by many to be the antithesis of his father in politics, but near, if not his equal in the field of battle.

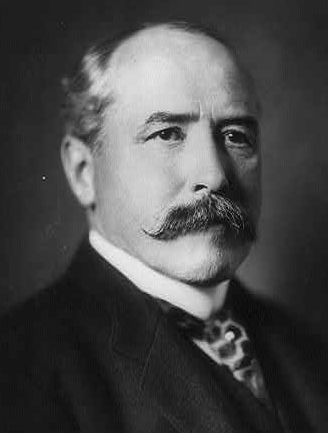

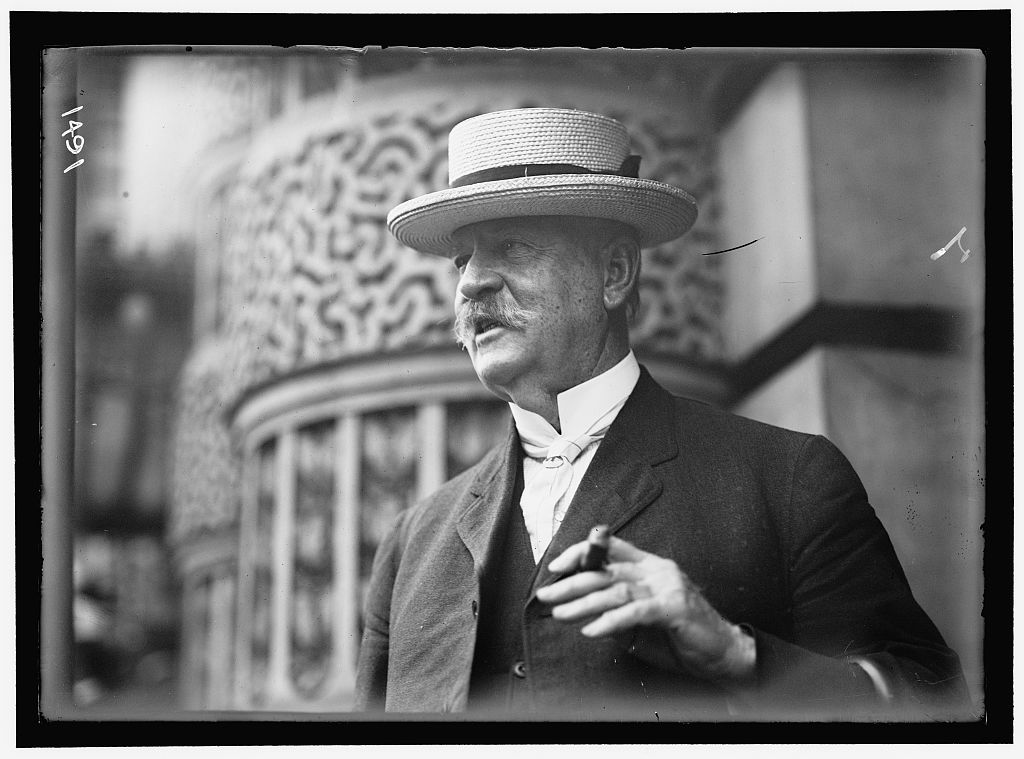

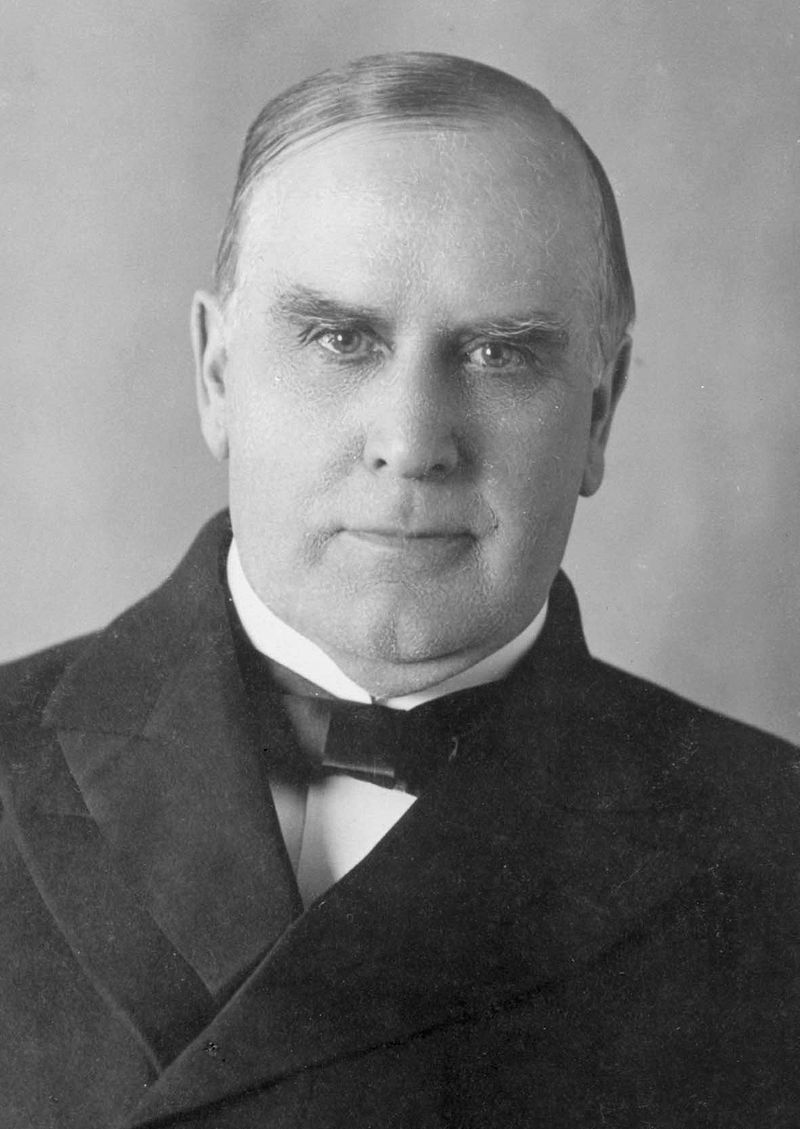

Charles E. Hughes: Among Roosevelt’s most ardent supporters, Hughes would continue in his seat as New York Governor until his appointment to the Supreme Court as an Associate Justice by Henry C. Lodge. He would be approached by the Republicans to be their candidate for the 1916 election, knowing he was a moderate who could appeal to both wings of the Republican Party, especially after the bitter division of the party in the 1912 election. Following this, Hughes would go to defeat Democratic candidate Delaware Senator Willard Saulsbury Jr. in the 1916 president election. Hughes would continue the policy of neutrality established by his predecessor, which he actually supported as he had no interest in entering the Great War. Hughes’ presidency would be a time of prosperity and economic growth, although Hughes was said to have wanted to return to the judiciary branch. He would make this clear by declining a second term, clearing the way for Calvin Coolidge’s nomination and ultimately his two terms in office. Many believe this helps explain Coolidge’s choice to nominate him to the Supreme Court as Chief Justice following the death of Philander Knox. Hughes would accept the post, and serve in it until his death in 1941.

John N. Garner: Buckner’s Secretary of the Interior would go on to achieve great things. First, he managed to be elected House Speaker in 1926, followed two years later by the Liberty Party nomination for the presidency, in which he won a narrow election against Theodore Bilbo. In office, he would take the first steps in what became the CSA Civil Rights Movement, although he certainly would not have realized it or claimed it as an achievement. He did this by sending in troops to, in his words, “keep order”, with the effect of protecting African-Americans who were being targeted because they held factory and other non-agricultural jobs, and were establishing churches, schools, and stores, which some citizens, including even his rival Bilbo, did not believe in and wanted to stop it via violence. This all was sparked by the CSA going through the effects of the Great Depression, although it was not hurt too badly, especially in comparison to Europe. Nonetheless, Garner would help guide his country through what ultimately became known in the CSA as the Panic of 1929, with most of his presidency focused on restoring the CSA’s industry. Ultimately, when his term concluded, industry was back on the rise, and he had a high approval rating.

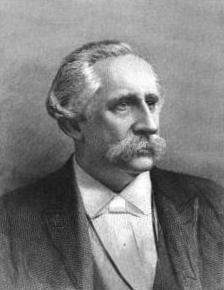

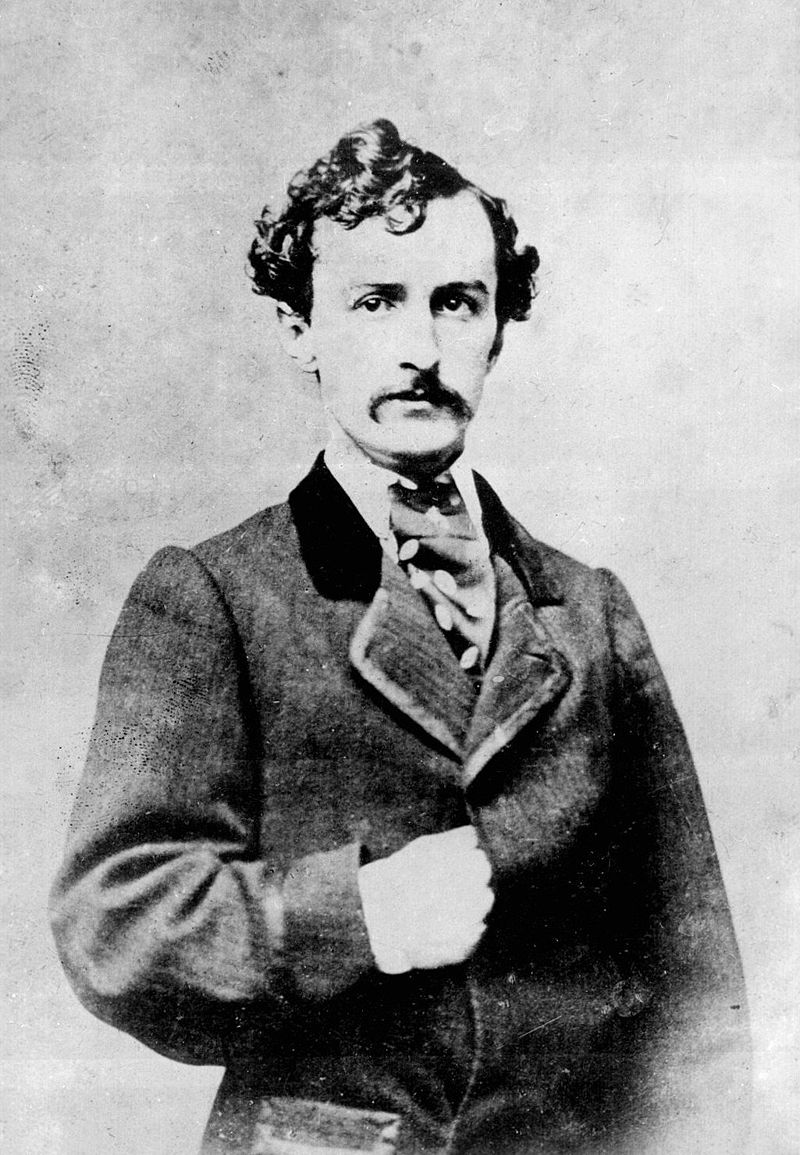

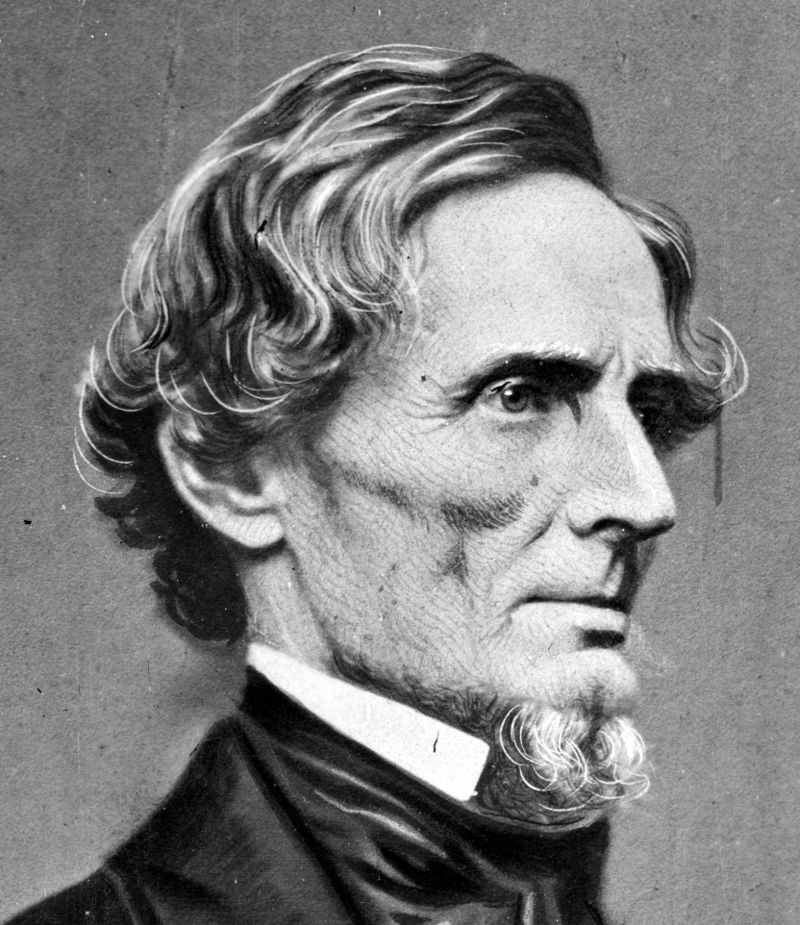

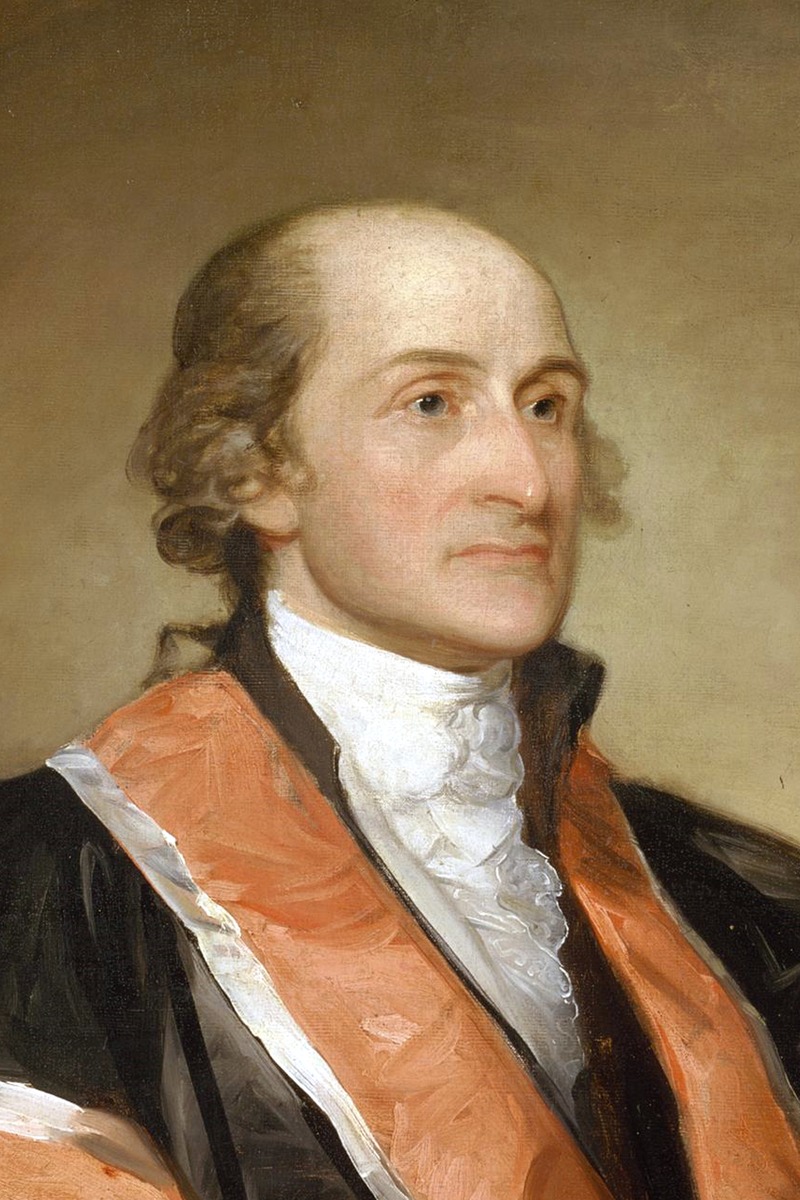

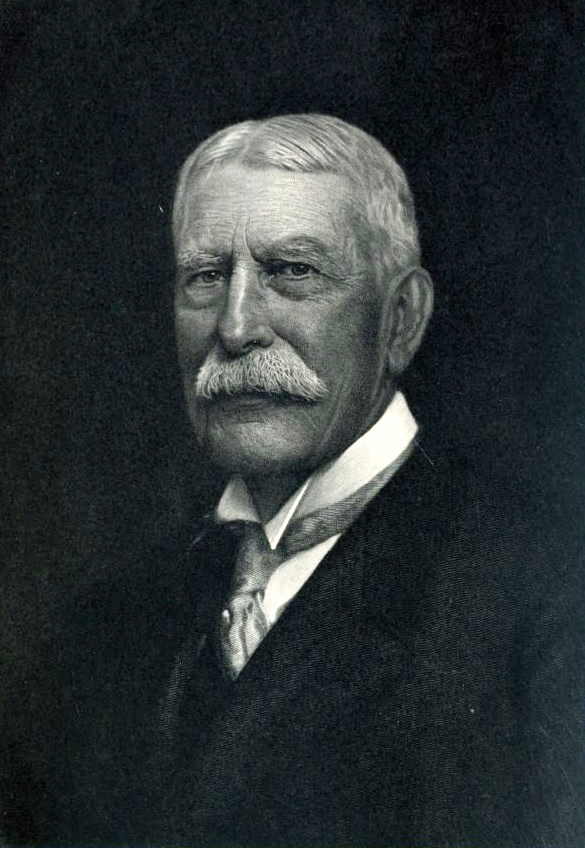

Grover Cleveland: Following the death of the Reform Party, Cleveland would say the following in 1907 about the party he once led, “It was a most interesting experiment. It attempted to force itself into the national eye, and it succeeded in doing so. It was a representation of what could occur when the American people banded together, and it nearly came to power. It is my firm belief that if Bryan had not been assassinated, people would be speaking of the Republican and Reform Parties, rather than the Republicans and Democrats. Even though the party ultimately abandoned me, and I ultimately abandoned the party, I still believe in the dream it stood for.” Cleveland would die two years later.

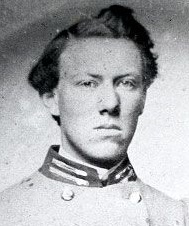

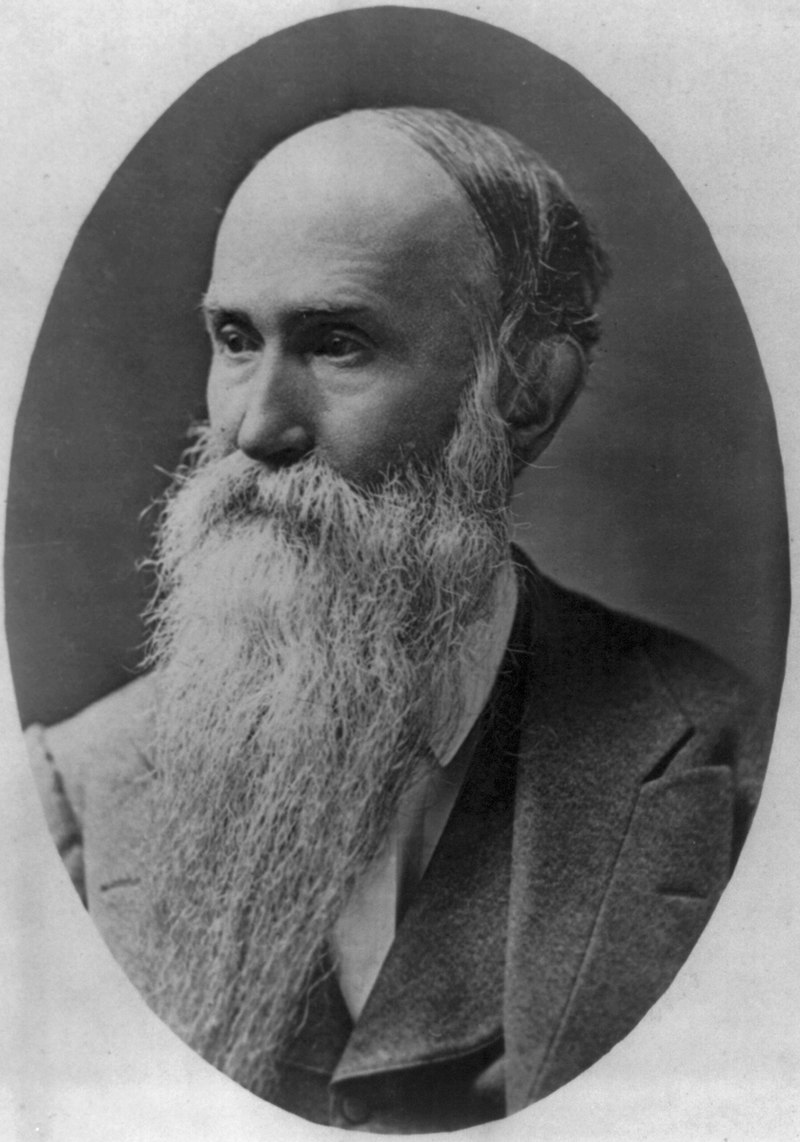

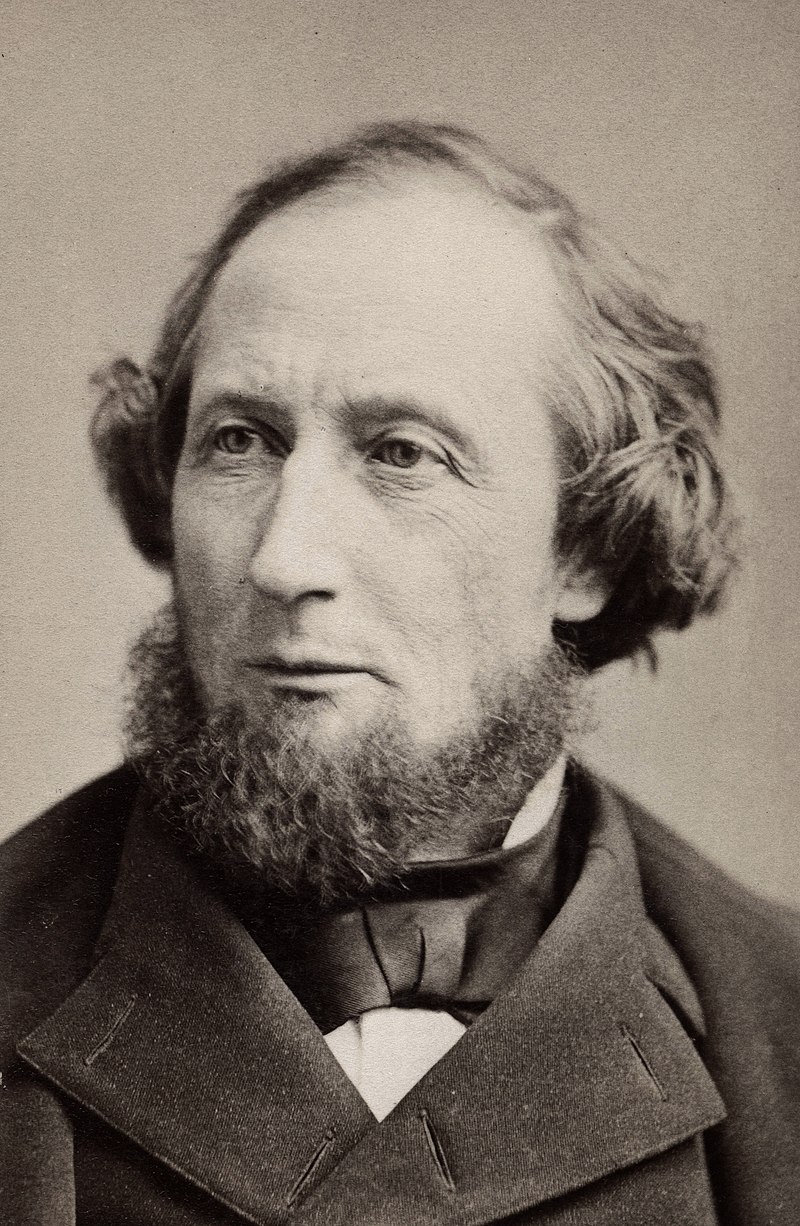

Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton: The man who was as close to Jackson as anyone else, and knew him as few others did would retire from politics a year after his now famous quip. In the 1916 and 1922 elections, efforts were made by the Liberty Party to attempt to convince him to agree to be their candidate for president. Pendleton, firmly in his retirement, would refuse all of these advances, and instead focus on his memoirs, as well as writing biographies of Jackson, Lee, Thomas, Longstreet, Stuart, D.H. Hill, A.P. Hill, and Ewell based on his wartime experiences. It was in the midst of writing his biography on Jackson that he had a stroke while writing about Jackson’s service in the Battle of Chancellorsville, causing him to redouble his efforts on his series on the Army of Northern Virginia’s top generals. It was in 1927 on the last book he intended on writing, his biography on Ewell, that his fatal stroke would occur, killing him in the midst of writing about Ewell’s service in the Shenandoah Valley. Pendleton would be referred to by subsequent historians as “The Last of the Romans”, representing one of the last members of the group of people who had actively served in the Civil War.