Sheba's Sons - Haile Selassie goes to Tokyo

Emperor Mikael Imru's decision to resurrect the likeness of His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I, as a statue at the African Union's headquarters in Addis Ababa has been a controversial one, especially on the sixty-first anniversary of Haile Selassie's death in 1945. The rising tide of anti-Western sentiment and ultranationalism in Ethiopia has seen a wave of revisionism sweep the country as well, placing those Axis collaborators - such as HS himself, Araya Abebe, Afawarq Gebre Iyasus, etc. - on a pedestal for attempting to better their countries in spite of the means they went about doing it. This includes the creation of the Imperial Ethiopian Army from Ethiopian refugees fleeing Italian-occupied Ethiopia and its subsequent fighting under Japanese command, adopting tenets from Shōwa Statism and National Socialism in the Provisional Government of Free Ethiopia that was established by the Emperor in exile in 1937 with the assistance of the Ikki Kita government.

Emperor Haile Selassie I was a reformist ruler who'd spent much of his Regency - since 1916 - centralizing power in his hands, subverting Empress Zewditu and her reactionary supporters in the Imperial Court who were fervently opposed to Ras Tafari Makonnen's proposals on modernization on the basis that it would compromise Ethiopian independence. In spite of the challenges he faced, the close of the 1920s had left him in a dominant position in the Imperial government with the death of Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis in 1927 and Zewditu's deteoriating health that ended with her death in 1930. Eventually, he acceded to the throne as Haile Selassie I in early November and vigorously continued his centralization initiatives that were being complemented by the introduction of reforms intended to restructure the Empire into a modern state on the Japanese model. By 1935, the Emperor directly controlled almost all of Ethiopia (sans Tigray) and was dedicating himself to its modernization with the cooperation of the intelligentsia - however, its course was put to a screeching halt with Mussolini's invasion in early October and Ethiopia's subsequent struggle for independence in vain.

Despite some successes and even reverses in the Christmas Offensive in December-January, there was no doubt in the outcome - that the sheer manpower and firepower of Fascist Italy was to overwhelm the poorly-trained and ill-equipped armies of Africa's last Empire. Despite a successful counterattack by the Imperial Bodyguard at Maichew [1] that left Italian forces reeling, the northern front collapsed with the Ethiopian armies there disintegrating or multiple units reinventing themselves as guerrillas under men like Lij Haile Mariam Mammo in the mountainous terrain's safety. It allowed Haile Selassie to contact the Japanese over the possibility of seeking asylum in Tokyo, the Japanese government initially hesitant to grant him such. Tokyo was eventually convinced to in the face of massive pro-Ethiopia protests that were enraged at the Italians' invasion and even led Hirohito to personally intervene in order to sanction giving the Ethiopian Emperor and his Ministers asylum in the Empire of Japan.

It was in Tokyo that the Ethiopian intellectuals accompanying Haile Selassie, most notably Heruy Wolde Selassie and Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariam, begun to absorb ideas from figures on the Japanese far-right, such as Ikki Kita and Seigo Nakano, and made contact with organizations like the Black Dragon Society. Considering the increasingly autocratic and militant nationalist stance the Ethiopian intellectuals had been gravitating toward, it is not exactly surprising to see them go even further right-wing but interestingly enough, contacts with Black nationalists through Japan's support for the former influenced them as well. It was through Malaku Bayan that the Ethiopian government-in-exile made contact with Marcus Garvey in Liberia [2] and Carlos Cooks in the United States, not to mention organizations like the Ethiopian Pacific Movement.

It was on this unfortunate path, in combination with the series of events that occurred from the Italian invasion and occupation, that led Haile Selassie and other Ethiopians on the path to collaboration with the Axis alliance through Ethiopian links with Japan that had evolved out of the marriage between Araya Abebe and Kuroda Masako [3] in 1936-37. With the outbreak of war with Europe in 1940, Haile Selassie had aligned himself firmly with his Japanese comrades and presided over the inauguration of the Imperial Ethiopian Army in 1941, a force of 40,000 Ethiopian soldiers gathered from the sizable Ethiopian community that had been settled throughout the Japanese Empire. It gained the unofficial name of "Sheba's Legion" when it was dubbed so by Marcus Garvey in 1941. It fought alongside the Indian National Army under Rash Behari Bose and then Subhas Chandra Bose under Japanese command in the Burma campaign where it managed to acquire a string of victories throughout 1942-43 before it was mauled in the attempted Japanese invasion of India and Allied reclamation of Burma.

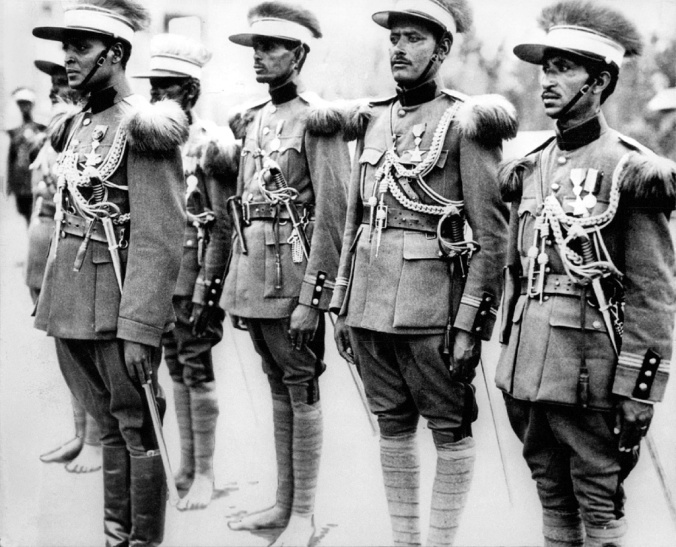

Sheba's Legion - or Sheba's Sons, as His Imperial Majesty fondly referred to them - stands at attention in Tokyo, 1941.

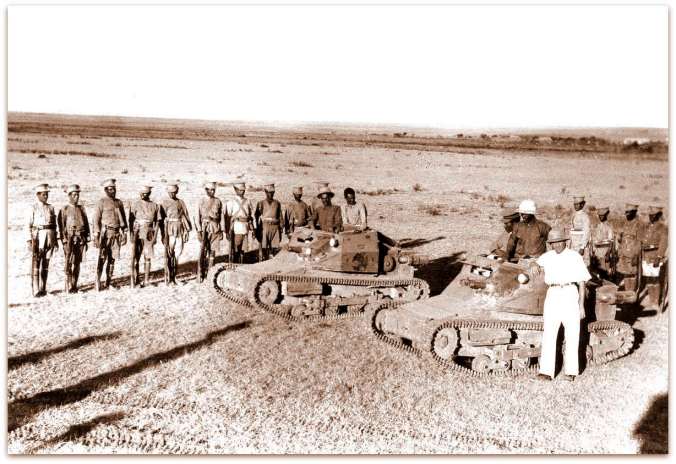

Ethiopian tankers equipped with Japanese tanks stroll through Japanese-occupied Burma, 1942-43.

----

[2] Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association is able to establish themselves in Liberia in 1927, not suffering the same financial troubles and deportation of Garvey as they did IOTL.

[3] I have plans for the planned marriage ITTL.

Last edited:

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-129092127-5a6f6a5ac064710037f0efe9.jpg)