I think the point @Duke of Orlando is making is not that Russia isn't going to see the utility of a railroad or rifles, but that they'll look at their debt following this war and their success in it and say, "Are these the things we need to spend money on right now?" And every investment not made now slows down future developments. Yes they can and will advance and might catch up or get ahead at some time in the future, but there's a solid chance that their evaluation of current events means that that time won't be now.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueThank you for saying more clearly the idea that I was trying to convey.I think the point @Duke of Orlando is making is not that Russia isn't going to see the utility of a railroad or rifles, but that they'll look at their debt following this war and their success in it and say, "Are these the things we need to spend money on right now?" And every investment not made now slows down future developments. Yes they can and will advance and might catch up or get ahead at some time in the future, but there's a solid chance that their evaluation of current events means that that time won't be now.

Hi, I'm new here, I don't know English at all other than a few simple sentences, but before the translator exists, I just want to give the opinion that this is the best story I've read and I hope you continue with this good content. next chapter.

Merry Christmas everyone!

Based on your depiction, a conspiracy or coup of some sorts against Aleksandr will probably still happen. What happens after that is where things might get a little more interesting.

Russian "Backwardness":

In my opinion this whole Imperial Russian Military backwardness tropic is a bit of a misnomer as they certainly weren't opposed to innovation in OTL in certain circumstances. In OTL, the Russians supported the construction of railroads and were among the first states in Europe to construct a railroad, building an 18 mile track from St. Petersburg to Tsarskeyo Selo in 1837 (only 2 years after the first German railroad, 9 years after the French, and 12 years after the British). By 1855, they had over 570 miles of track spanning the countryside.

They also invested heavily in Paixhans guns, using them to great effect in the OTL Battle of Sinop and they used the Jacobi naval mines extensively in the Gulf of Finland, deterring Anglo-French attacks on Kronstadt and St. Petersburg. They weren't strangers to rifles either with nearly 2 percent of their troops wielding German made rifles, but these were usually allocated to the Guards Divisions which were normally stationed far from the front lines. Russia's real issues were largely overconfidence, an outdated military doctrine, and supply limitations not an aversion to military modernization or innovation.

First and foremost, Russia had been incredibly successful militarily in the first half of the 19th Century. Although they suffered a few humiliating defeats early on to Napoleon in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Coalition Wars; they repaid these defeats in kind with their great victories in 1812, 1813, and 1814 respectively. Moreover, Russia had been incredibly successful fighting against the Ottomans and the Persians in the intervening years, making great gains at relatively little expense. While they certainly had reason to be proud of their earlier triumphs, this made them incredibly arrogant and prone to mistakes.

This carried over to their military doctrine which wrongly believed that massed ranks of soldiers wielding muskets and bayonet charges could still carry them to victory, even though the times had clearly begun to change. This was largely a result of Tsar Nicholas' love for Military drill. He really enjoyed the pomp and pageantry of soldiers marching in parades, wearing impeccable uniforms, and brandishing their polished muskets with bayonets fixed. This carried over to the Russian training manual which required soldiers to maintain proper decorum and discipline even in the thick of battle so as to not disrupt the cohesion of their formation. If they failed to do so, they would be punished severely, with many receiving lashes for the slightest offense. While this might have been successful in early conflicts, it was no longer relevant by the 1850's. Ironically, the Russians would realize some of these mistakes in the Crimean War and began addressing some of them (they attempted to produce their own rifles to counter the Minie Rifle in 1855), but by that point it was too late to make a decisive difference in the war.

This was made worse by the fact that most of the Russian soldiers were illiterate serfs who likely didn't know how to fire their weapons. During peacetime, they received about 10 rounds a year to practice their shooting. Depending on their post, they may receive more or they may receive less, they usually received less. This wasn't helped by the vainglorious officer corps of the Russian Army which had no qualms about throwing away hundreds or thousands of lives if it brought them personal honor and accolades.

Finally, the Russians suffered from severe supply issues throughout the Crimean War. This was nothing new for Russia and their defeat in the Crimean War would do little to resolve this issue as they would still suffer from shortages well into the 20th Century. A large part of this problem was the appalling lack of industry in Russia, but another issue was lack of funding. Despite its great size, the Russian Army was chronically underfunded, to the point where the average soldier was constantly in arrears. As a result, the soldiers had to take care of themselves as the government either didn't have the capability or interest to do so. Fortunately, many of them were skilled tailors, bakers, carpenters or hunters who could provide some limited care to their compatriots. Nevertheless, the Russian Army suffered extensively from disease and malnutrion throughout the entire OTL Crimean War, sapping its fighting ability considerably.

I will definitely continue this story, in fact the next chapter will be ready very, very soon.

This is an incredibly thorough analysis, thank you Damian!I personally don't think it would, honestly. We're dealing less with issues of governance (which is still important, mind you), and more with issues of people and personalities. Heck, a victorious Russia could make things worse, given how among the influential in Serbia we have Francophiles, Russophiles, Austrophiles, etc. However, there is one aspect that could possibly shift things significantly. Following the Crimean War OTL, at the 1856 Treaty of Paris, the Russian protectorate (read: protection of its rights and neutrality) over the country was expanded over the other signers, those of course being Britain, France, Austria, Prussia and Sardinia. Alongside that, the guarantee of freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube was also important.

When the Tenka Conspiracy occurred in the fall of 1857, and failed, the Prince took the opportunity to strike against his Privy Council (of whom all but three were against the Prince, and some partook in the conspiracy) by making them resign due to being compromised (and if they didn't resign, they'd be arrested), despite not being involved. Six were specifically named to resign, those being Lazar Arsenijević, Stevan Magazinović, Jovan Veljković, Stojan Jovanović Lešjanin, Živko Davidović and Gavrilo Jeremić, which they did, while three more were considered compromised (including Aleksa Simić and Ilija Garašanin). Only four council members were considered safe, and we needn't mention the actual conspirators who were swiftly arrested and sentenced to life (originally death, until the Porte's intervention) upon the discovery of the conspiracy, leading them to Gurgusovac Tower in Knjaževac, where public opinion shifted on the convicted, going from loathing for what they had done (especially given a high-ranking official was at the head of the conspiracy), to sorrow for the cruel treatment they received in the tower's dungeon (to the point one of them died). With spots empty in the Privy Council, the Prince filled them all with loyalists.

The Prince had the opportunity to confirm his new power he had gained through law, but before he could, the trans-council opposition decided to appeal to the Great Powers and point to the fact that the Prince had carried out a coup d'état. OTL this resulted in France approaching Russia, interested in helping the Russians suppress Austrian influence in Serbia, as the prince's policies were Austrophilic. The two demanded the intervention of the Porte, in the same fashion they had done back in 1838 with Miloš and the Turkish Constitution. The Porte appointed Etem Pasha as commissioner to go and investigate, with the hope that they can be the ones to judge the situation, and avoid the Europeans sending one instead. Etem Pasha would go as far to threaten the Prince with his replacement, and thus, the Prince was forced to not only pardon the conspirators and hand them to Etem Pasha, but to also allow the deposed council members to return to the Privy Council. With momentum high, the opposition organized itself enough to convene the Saint Andrew Assembly, and finally replaced the Prince.

I'll say, first things first, I don't think there is a chance the conspiracy can succeed if it follows per OTL. They literally just hired some peasant from the Kragujevac area, Milosav Petrović, and just gave him what he needed to kill the Prince, but the man instead just went to Belgrade and began blackmailing the conspirators, taking upwards of 1000 ducats from them. And soon after, Milosav's brother-in-law found out and reported this situation to the authorities, leading to their imprisonment. The Porte's word might mean less now that their garrisons are out of the country TTL, but I imagine they'd still intervene to prevent the executions of the conspirators, thus leading to the same sort of shift of opinion that we saw OTL when they were sent to Gurgusovac Tower (which would just add further to the general dissatisfaction regarding the King, and further support for the return of Obrenović, whom unbeknownst to the populace had financed the conspiracy, while everyone else just thought Tenka wanted to establish a noble republic with him as its head). But the big change would be what would happen after the Prince decides to take advantage of the situation and fill the Privy Council with loyalists, since I imagine the other European powers not wanting Russia to decide alone (especially given the war just now), and while Austria may still have interests in Italy, I don't know if that would be enough to push France to get involved. And again, the Porte's slightly lessened influence due to the garrisons being out might embolden the Prince to stick it out, though dynamics may or may not influence what the opposition might do.

Given the circumstances, I still think it is inevitable that Aleksandar will be deposed, it's just that the process to it might now look a bit different. The writing was on the wall, so to say, you just need someone to interpret it because it reads like chicken scratchings.

Based on your depiction, a conspiracy or coup of some sorts against Aleksandr will probably still happen. What happens after that is where things might get a little more interesting.

Russian "Backwardness":

In my opinion this whole Imperial Russian Military backwardness tropic is a bit of a misnomer as they certainly weren't opposed to innovation in OTL in certain circumstances. In OTL, the Russians supported the construction of railroads and were among the first states in Europe to construct a railroad, building an 18 mile track from St. Petersburg to Tsarskeyo Selo in 1837 (only 2 years after the first German railroad, 9 years after the French, and 12 years after the British). By 1855, they had over 570 miles of track spanning the countryside.

They also invested heavily in Paixhans guns, using them to great effect in the OTL Battle of Sinop and they used the Jacobi naval mines extensively in the Gulf of Finland, deterring Anglo-French attacks on Kronstadt and St. Petersburg. They weren't strangers to rifles either with nearly 2 percent of their troops wielding German made rifles, but these were usually allocated to the Guards Divisions which were normally stationed far from the front lines. Russia's real issues were largely overconfidence, an outdated military doctrine, and supply limitations not an aversion to military modernization or innovation.

First and foremost, Russia had been incredibly successful militarily in the first half of the 19th Century. Although they suffered a few humiliating defeats early on to Napoleon in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Coalition Wars; they repaid these defeats in kind with their great victories in 1812, 1813, and 1814 respectively. Moreover, Russia had been incredibly successful fighting against the Ottomans and the Persians in the intervening years, making great gains at relatively little expense. While they certainly had reason to be proud of their earlier triumphs, this made them incredibly arrogant and prone to mistakes.

This carried over to their military doctrine which wrongly believed that massed ranks of soldiers wielding muskets and bayonet charges could still carry them to victory, even though the times had clearly begun to change. This was largely a result of Tsar Nicholas' love for Military drill. He really enjoyed the pomp and pageantry of soldiers marching in parades, wearing impeccable uniforms, and brandishing their polished muskets with bayonets fixed. This carried over to the Russian training manual which required soldiers to maintain proper decorum and discipline even in the thick of battle so as to not disrupt the cohesion of their formation. If they failed to do so, they would be punished severely, with many receiving lashes for the slightest offense. While this might have been successful in early conflicts, it was no longer relevant by the 1850's. Ironically, the Russians would realize some of these mistakes in the Crimean War and began addressing some of them (they attempted to produce their own rifles to counter the Minie Rifle in 1855), but by that point it was too late to make a decisive difference in the war.

This was made worse by the fact that most of the Russian soldiers were illiterate serfs who likely didn't know how to fire their weapons. During peacetime, they received about 10 rounds a year to practice their shooting. Depending on their post, they may receive more or they may receive less, they usually received less. This wasn't helped by the vainglorious officer corps of the Russian Army which had no qualms about throwing away hundreds or thousands of lives if it brought them personal honor and accolades.

Finally, the Russians suffered from severe supply issues throughout the Crimean War. This was nothing new for Russia and their defeat in the Crimean War would do little to resolve this issue as they would still suffer from shortages well into the 20th Century. A large part of this problem was the appalling lack of industry in Russia, but another issue was lack of funding. Despite its great size, the Russian Army was chronically underfunded, to the point where the average soldier was constantly in arrears. As a result, the soldiers had to take care of themselves as the government either didn't have the capability or interest to do so. Fortunately, many of them were skilled tailors, bakers, carpenters or hunters who could provide some limited care to their compatriots. Nevertheless, the Russian Army suffered extensively from disease and malnutrion throughout the entire OTL Crimean War, sapping its fighting ability considerably.

They'll certainly try, but whether they succeed or not is for me to know and you all to find out.Do the Greeks get Constantinople at the end?

Thank you very much, I'm incredibly flattered by your kind words!Hi, I'm new here, I don't know English at all other than a few simple sentences, but before the translator exists, I just want to give the opinion that this is the best story I've read and I hope you continue with this good content. next chapter.

I will definitely continue this story, in fact the next chapter will be ready very, very soon.

Wonderful news to see your come back and joyeux Noël !Merry Christmas everyone!

This is an incredibly thorough analysis, thank you Damian!

Based on your depiction, a conspiracy or coup of some sorts against Aleksandr will probably still happen. What happens after that is where things might get a little more interesting.

Russian "Backwardness":

In my opinion this whole Imperial Russian Military backwardness tropic is a bit of a misnomer as they certainly weren't opposed to innovation in OTL in certain circumstances. In OTL, the Russians supported the construction of railroads and were among the first states in Europe to construct a railroad, building an 18 mile track from St. Petersburg to Tsarskeyo Selo in 1837 (only 2 years after the first German railroad, 9 years after the French, and 12 years after the British). By 1855, they had over 570 miles of track spanning the countryside.

They also invested heavily in Paixhans guns, using them to great effect in the OTL Battle of Sinop and they used the Jacobi naval mines extensively in the Gulf of Finland, deterring Anglo-French attacks on Kronstadt and St. Petersburg. They weren't strangers to rifles either with nearly 2 percent of their troops wielding German made rifles, but these were usually allocated to the Guards Divisions which were normally stationed far from the front lines. Russia's real issues were largely overconfidence, an outdated military doctrine, and supply limitations not an aversion to military modernization or innovation.

First and foremost, Russia had been incredibly successful militarily in the first half of the 19th Century. Although they suffered a few humiliating defeats early on to Napoleon in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Coalition Wars; they repaid these defeats in kind with their great victories in 1812, 1813, and 1814 respectively. Moreover, Russia had been incredibly successful fighting against the Ottomans and the Persians in the intervening years, making great gains at relatively little expense. While they certainly had reason to be proud of their earlier triumphs, this made them incredibly arrogant and prone to mistakes.

This carried over to their military doctrine which wrongly believed that massed ranks of soldiers wielding muskets and bayonet charges could still carry them to victory, even though the times had clearly begun to change. This was largely a result of Tsar Nicholas' love for Military drill. He really enjoyed the pomp and pageantry of soldiers marching in parades, wearing impeccable uniforms, and brandishing their polished muskets with bayonets fixed. This carried over to the Russian training manual which required soldiers to maintain proper decorum and discipline even in the thick of battle so as to not disrupt the cohesion of their formation. If they failed to do so, they would be punished severely, with many receiving lashes for the slightest offense. While this might have been successful in early conflicts, it was no longer relevant by the 1850's. Ironically, the Russians would realize some of these mistakes in the Crimean War and began addressing some of them (they attempted to produce their own rifles to counter the Minie Rifle in 1855), but by that point it was too late to make a decisive difference in the war.

This was made worse by the fact that most of the Russian soldiers were illiterate serfs who likely didn't know how to fire their weapons. During peacetime, they received about 10 rounds a year to practice their shooting. Depending on their post, they may receive more or they may receive less, they usually received less. This wasn't helped by the vainglorious officer corps of the Russian Army which had no qualms about throwing away hundreds or thousands of lives if it brought them personal honor and accolades.

Finally, the Russians suffered from severe supply issues throughout the Crimean War. This was nothing new for Russia and their defeat in the Crimean War would do little to resolve this issue as they would still suffer from shortages well into the 20th Century. A large part of this problem was the appalling lack of industry in Russia, but another issue was lack of funding. Despite its great size, the Russian Army was chronically underfunded, to the point where the average soldier was constantly in arrears. As a result, the soldiers had to take care of themselves as the government either didn't have the capability or interest to do so. Fortunately, many of them were skilled tailors, bakers, carpenters or hunters who could provide some limited care to their compatriots. Nevertheless, the Russian Army suffered extensively from disease and malnutrion throughout the entire OTL Crimean War, sapping its fighting ability considerably.

They'll certainly try, but whether they succeed or not is for me to know and you all to find out.

Thank you very much, I'm incredibly flattered by your kind words!

I will definitely continue this story, in fact the next chapter will be ready very, very soon.

Chapter 84: Breaking Point

Chapter 84: Breaking Point

Russian Cavalrymen Pursue Fleeing Ottoman Soldiers

The start of the 1856 campaigning season would begin a little later than the previous year. Having already fulfilled most of his objectives, and much more, General Nikolay Muravyov would instead allow his exhausted soldiers time to rest and recuperate after a year and a half of almost constant fighting and marching in extremely difficult terrain and weather. Beyond this, however, his dreadfully long supply lines simply made it impossible to keep pushing westward at the rate he had in 1855. Instead, the Russian Army of the Caucasus would be refocused outwards once Spring arrived in Anatolia, expanding its narrow salient to both the North and the South.

In the south, a portion of the Russian Army under Prince Vasily Osipovich Bebutov would successfully reduce the Beyazit salient by the end of May. Resistance in the area had been rather sporadic as the Ottomans had largely evacuated their remaining troops from the region over the Winter. After Beyazit’s fall on the 15th of April, Bebutov was instructed to begin pushing southwards toward Lake Van and then onward to the cities of Mush and Van if possible. However, his offensive here would run into increasing trouble, more so from the rugged terrain and local Kurdish bandits than any official Ottoman resistance. Prince Bebutov’s detachment would eventually reach the northeastern corner of Lake Van by the end of June, near the submerged town of Ercis.[1] However, rather than press onward as originally instructed, Bebutov would receive new orders from St. Petersburg to halt his advance in place and began digging in.

Another Russian detachment under Prince Ivan Andronikashvili would press against Reshid Pasha’s forces stationed in the hills west of Erzincan. His efforts were largely focused on tying down Turkish forces in the region, rather than making a concerted push in any particular direction. Despite this, the general weakness of the Ottoman defenders enabled relatively modest gains for the Russians along this front. Their largest drawbacks were constant supply shortages, which gave the Ottomans a slight advantage in firepower, but overall, the Russians still maintained the edge here. By the end of June, Prince Andronikashvili had managed to reach the outskirts of Gercanis, roughly 18 miles West from where he first started his campaign in April. Even still, he had succeeded in his primary objective, as Reshid Pasha and Selim Pasha were unable to send any significant reinforcements to assist in the defense of the Lazistan or the Van Eyalets.

The main Russian objective of the Anatolian front in 1856 was the Pontic coast, however, with the port of Trabzon being of particular importance to St. Petersburg given its status as a prominent commercial hub. As the Porte’s premier Black Seas port, it would provide Russia with great wealth and influence over all trade in the region if captured. The Ottoman commanders in the region recognized Russia’s interest in the port and had used the extended lull in the fighting to fortify the passes through the Pontic Mountains against the coming Russian offensive. But with their shattered armies and dreadful morale, there was little the beleaguered Ottomans could do in the face of the impending Russian juggernaut.

Beginning on the 10th of April, General Muravyov took 54,000 men northward and began his assault on the Pontic Coast. Despite significant support from the British Royal Navy and the Ottoman Black Seas Fleet, the port of Batumi would fall within a month’s time. The nearby town of Rize would also come under considerable pressure soon after. Like Batumi before it, Rize would surrender to the Russians after a month-long siege at the end of May. Muravyov’s attempts to take Trabzon, however, would encounter more resistance as the last battered remnants of Mehmed Pasha’s Army along with various British marines and sailors, and a number of Circassian, Crimean, Dagestani, and Lazi irregulars stood against them.

Moreover, the British Royal Navy and Ottoman Black Seas Fleet would position several ships off the coast of Trabzon. Despite the risk from Russian guns on land, the allied ships frequently bombarded the approaching Russian Army, effectively deterring any concentrated attempts to take the city by storm. Similarly, a constant stream of supply ships into and out of Trabzon’s harbor ensured that the city was well provisioned, mitigating the risk of it falling to starvation. Nevertheless, Muravyov was a tenacious general and continued the siege, steadily moving his lines forward, inch by inch over the course of several weeks. By mid-June, the threat to Trabzon was real enough that the British dispatched several regiments from the Balkans to help defend the city despite the perilous situation in Rumelia.

The arrival of these British soldiers in Trabzon would ironically coincide with a decisive shift in priorities by the Russian Government away from the Caucasus and Anatolia. Men and resources previously allocated to the Caucasus Front were now being drawn off to fight in other areas, with entire divisions now being recalled for service in the Balkans, the Baltic and Central Asia. Even General Muravyov was ordered northward to lead the upcoming Fall campaign against the Caucasian Imamate and the Circassian Confederacy. His departing address to his soldiers was brief and blunt, but still a highly emotional event for his soldiers who had come to respect and admire the Old Bear, General Muravyov.

Despite the great success for the Russians on the Anatolian front, it came to a quiet end in early July 1856. Barring Trabzon, all of Russia’s pre-war objectives for this front had been fulfilled and then some after two years of bitter fighting. As such few, if any, in St. Petersburg had the will or the interest to continue investing desperately needed resources into this theater, beyond what was necessary to hold their new gains. Tsar Nicholas was personally against a continued offensive into the increasingly Muslim countryside of Central Anatolia especially when more vital fronts like the Balkans needed further support. In truth, this decision had been made over the Winter; the continued success by Muravyov’s men in the Spring and Summer only quickened this process.

The Anatolian Front in the Summer of 1856

As a result of this, Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov’s Army of the Danube would receive the bulk of Russia’s remaining resources in 1856. Reinforced with four newly raised Reserve Divisions, Gorchakov’s army was boosted well above three hundred thousand soldiers by the start of Spring Campaigning season. It would also receive priority over the other field armies for munitions and equipment, helping to sure up their lacking stockpiles of musket balls, cannon balls, powder, food, clothing, shoes and other commodities. A few of its units would even receive the newly minted Model 1856 Six Line Rifle-Muskets which had been rushed out of development to counter the British Enfields. Finally, Gorchakov was given free rein to expand the front to the entire stretch of the Danube from Silistra to the Iron Gates. With his army reinforced, resupplied, and redirected, Prince Gorchakov readied his men for the fight of their lives in late mid-April.

This year’s offensive in the Balkans would begin with another Russian assault on Silistra’s defenses by Count Alexander von Lüders’ Army of Moldavia, supported by General Karl Schilder’s extensive Corps of Artillery. Boasting over 400 cannons (mostly smaller calibers and older vintage guns), the Russian bombardment peppered the Allied lines with fire and iron in preparation for the Russian offensive. The ensuing attack on the 24th of April would be directed against the entirety of the Anglo-Ottoman line, probing it for vulnerabilities and searching for any openings. However, unlike the foolhardy attacks of the year prior, this onslaught would be a meticulous campaign meant to wear down the resolve and the strength of the Allied defenders over time. Although it would cost them a tremendous amount in blood, the Russians had blood enough to spare.

They need not try too hard, however, as the British rank and file were in dismal spirits by the start of 1856. Many of their comrades had died of cholera and typhus over the last year, while many more were sent to Scutari to recuperate or invalidated home before being unceremoniously discharged from the service. Several leading officers would abandon the Army under the guise of illness or injury, while others like the Duke of Cambridge were recalled for political reasons further weakening British morale and discipline.[2] The continuous skirmishing with the Russians over the Winter didn’t help either. Were it not for the stalwart leadership of General Brown, many of his men would have likely mutinied or deserted in the face of the looming Russian attack.

British Soldiers “Celebrating” Another Year in Silistra

Defeatism was also quite rampant in the Turkish ranks as the continuous stream of bad news from Eastern Anatolia poured in over the Fall and Winter, destroying the already fragile Ottoman morale. Similarly, relations with London had soured immensely after they had coerced the Sublime Porte into ceding territory to the Kingdom of Greece. Although, the influx of additional British coin and weapons into the Ottoman Empire would help soothe the ruffled feathers in Constantinople, many of the Ottoman troops along the Danube were now distrustful of their British allies, whom they considered fair weather friends and opportunists. Despite this, many troops in the Ottoman Army remained committed to the war effort if for no other reason to defend their homes and their families. Some were motivated purely by spite, with the Poles largely fighting to injure the Russians after decades of oppression and persecution.

Fortunately, the Allies would receive a desperately needed boost in late April/early May with the arrival of the British 6th Infantry Division - the “Irish Division” - and the British Foreign Legions which would help restore the British Army’s flagging morale and strength. The British Army in the Balkans would in fact top 100,000 soldiers briefly before attrition and redeployments to India reduced it to around 68,000 men. Most of the British reinforcements would be stationed along the Danube front, with most being allocated to the defense of Silistra. A handful of regiments were sent to fortify the ports of Varna and Burgas, and the fortress of Shumen, while a brigade was sent to help defend the river crossings further west. The collapse of the Anatolian front the year prior, would also force General Brown to dispatch a few brigades of the British Foreign Legion eastwards to aid in the defense of Trabzon.

The Ottomans would also call up the garrisons of Thessaly, Epirus, and Serbia for field duty after the recent treaties with Serbia and Greece. Unfortunately, while these men were trained fighters, they were generally second-rate troops who had been relegated to guard duty and police work. They would also receive another 11,000 volunteers from Albania, Bosnia, North Africa, and the Levant, but nearly two thirds were directed to the Anatolian front, providing little assistance to Omar Pasha. Moreover, these men were Bashi-bazouks, undisciplined mobs more interested in plunder and personal glory than victory or strategic gains. Despite their rowdiness, the Porte could not turn these men away when it desperately needed bodies to hold the line against Russia.

Through some miracle, the Anglo-Ottoman lines outside Silistra held against Count Lüders’ attack as they rushed these new arrivals into the fray. In doing so, however, they had fallen for Prince Gorchakov’s trap as Lüders’ offensive was merely the anvil to Gorchakov’s hammer. As this offensive was taking place, Prince Gorchakov dispatched the Russian Army of Wallachia under General Fyodor Sergeevich Panyutin to force additional crossings upriver. General Dannenberg and the Russian 4th Corps would resume their offensive from last year, marching on Silistra from the village of Tutrakan. Simultaneously, the 2nd Reserve Division under General Alexander Adlberberg and the 3rd Reserve Division under General General Wilhelm Bussau would move against the cities of Vidin and Oryakhana respectively. However, General Panyutin’s true hammer blow would fall on the fortress city of Ruse.[3]

The City of Ruse in the early 19th Century

The city of Ruse was a major port along the Danube river, serving as both a prominent trade hub in the region and a crossroads for all traffic going up and down and across the Danube. Most importantly it sat on the road between Bucharest and Constantinople, giving it incredible value to both sides. As a result of its strategic location; Romans/Byzantines, Bulgarians, and Ottomans alike would all invest much into securing this region against any northern aggressors. Under the Ottomans, Ruse developed a thriving shipbuilding industry and quickly became their chief administrative center along the lower stretch of the Danube.

Like Silistra, Varna and Shumen, it had been heavily fortified during the 1830’s and early 1840’s seeing the construction of several polygonal fortresses outside the city’s medieval walls, which were themselves updated and expanded as well. It also boasted a sizeable garrison prior to the war, with two regiments of infantry and a regiment of artillery for a total of 8,000 soldiers. However, the War would see the infantry regiments drawn away to aid in the defense of Silistra, reducing Ruse’s garrison by more than two thirds. Fortunately, the garrison would be reinforced with the arrival of troopers from Thessaly and Serbia along with volunteers from Macedonia and Albania boosting their number well above 5,000 just in time for Russian General Stepan Khrulev’s attack on the 1st of May.

The attack by General Khrulev’s Russian 2nd Corps would meet with some moderate success initially as the Russians quickly reclaimed the Wallachian island of Ciobanu which had been had captured by Omar Pasha at the very start of this War. However, their efforts to reach the walls of Ruse would be repelled after a fierce firefight as the Ottoman garrison released a small fleet of boats and barges to disrupt the Russian crossing here. Eventually, the Russians would cross the river, but here they fell into an Ottoman trap as Ruse's riverside defenses were especially strong, with dozens of cannons and carefully prepared kill-zones which cut the Russian vanguard to ribbons. Unable to make much progress against Ruse, General Khrulev dispatched the 1st Infantry and 2nd Grenadier Divisions to force another crossing further West near the port of Sistova (Svishtov).

Unlike at Ruse, the Russian crossing at Sistova would meet with much more success as the town was only protected by a company of Turkish soldiers stationed at old Tsarnevets castle. As was the case in 1810 and 1829, the Russian soldiers quickly stormed the castle’s medieval walls, brushing aside the undermanned and unprepared Ottoman garrison with relative ease. With a firm beachhead across the Danube now secured, Khrulev released the 1st Uhlan Division to fan out across the countryside, searching for any Turkish pickets on the road to Ruse. When they returned with no such news, Khrulev ordered his Corps across the Danube, leaving the 4th Division behind to screen Ruse from the North. Seven days later on the 15th of May, Khrulev’s Corps would reconverge outside the southern outskirts of Ruse, effectively surrounding it from all sides.

Russian Soldiers crossing the Danube near Ruse

Whilst Ruse’s defenses were quite robust, aided as they were by the swift Danube currents and months of preparation; the city’s garrison was still quite undermanned, numbering only 5,671 men at this point, compared to the nearly 68,000 Russians gathered outside their walls. In spite of these tremendous odds, the Ottoman garrison was able to resist the Russian onslaught for several days. Moreover, Khrulev’s siege lines were not air tight during the first few days of the siege, enabling Ottoman messengers to escape to Silistra.

Word about Ruse’s plight would soon reach the ears of Omar Pasha and General Brown, but given their own dire situation at Silistra, there was little the Allied Commanders could do. They simply lacked the resources to counteract Lüders’ ongoing offensive from the East, Dannenberg’s continued push from the West, and now this maneuver by Khrulev against Ruse. Nevertheless, they endeavored to send whatever help they could to Ruse, but their effort would come too late. With Ruse surrounded, Khrulev steadily chipped away at the Ottoman defenses, until finally, on the 5th of June he released his entire Corps upon the city of Ruse. The defenders fought desperately, but eventually succumbed to the insatiable tide of the Russians, leading to their surrender.

With Ruse’s fall, the Russians had gained a major junction across the Danube, albeit one that was further West than they would have preferred. Nevertheless, its capture provided an alternative to Silistra, enabling the Russians to ferry over large quantities of men and munitions unhindered. It also forced the already beleaguered British and Ottomans to stretch their forces even further to defend their now dangerously exposed western flank, lest Panyutin's Army march on Constantinople unopposed. After a week’s pause to rest his forces, General Khrulev directed his cavalry southward towards Tarnovo and westward against Pleven, inciting the local Bulgarians to revolt as they went.

Several days later, General Panyutin would send word to Khrulev instructing him to travel eastward with his Corps and link up with General Dannenberg’s 4th Corps. Thereafter, they would converge on Silistra from both the West and South, cut its supply lines, and finally surround the city. Unfortunately for Panyutin, a deserter from the Russian camp, believed to be a Polish officer, leaked much of this battleplan to Omar Pasha and General Brown. Although the exact extent of the Russian operation was unknown to them, they recognized that they would be doomed if Panyutin’s Army was allowed to reach Silistra uncontested. Despite the risk, they knew that this was their last chance to force the Russians back. Pinning everything on this next campaign, both Omar Pasha and General Brown opted to march out of Silistra and face the Russians head on.

Ottoman Soldiers Receive their New Orders

The Ottoman Army of Rumelia, under Omar Pasha would sally out against Count Lüders’ Host, holding it in place whilst General Brown’s Balkan Expeditionary Force would march against General Dannenberg’s 4th Corps - which was dangerously exposed - and destroy it before it could rejoin with the rest of Panyutin’s army. Setting out on the 9th of June, Brown’s Army would catch Dannenberg by surprise outside the village of Vitren. In the ensuing battle, the Russian 4th Corps would be thoroughly defeated by the British, but in spite of its extensive losses - losing over a quarter of its men to death, desertion, or capture – Dannenberg’s Corps would manage to retreat in relatively good order. Opting to pursue it, General Brown and the British Army would chase the fleeing 4th Corps for the next four days, fighting a series of skirmishes and minor engagements with the Russian rearguard before finally catching them near the hamlet of Ryakhovo located on the banks of the Danube.

With Dannenberg’s men now trapped between the British Army and the Danube, General Brown hoped to smash them to pieces and then turn his attention to Khrulev’s 2nd Corps. Unfortunately, much of his own army had become strung out across the countryside over the last few days, leaving him with three divisions (1st, 4th, and 6th) to fight against four weakened Russian divisions. Whilst he initially contemplated waiting for the rest of his army to catch up, time was now against him as his scouts reported that Panyutin’s Army of Wallachia had left Ruse and was now marching to Dannenberg’s aid. Spurred on to crush Dannenberg’s weakened Corps before the rest of the Russian Army arrived, General Brown ordered an immediate attack on the Russian position.

Despite their dire predicament, the Russians were in relatively good spirits, and held their ground against the advancing British for several hours. As the day progressed, the fighting grew more desperate as the veteran Highlander Brigade smashed through the thin Russian line in multiple places. While it seemed as if the battle was lost for the Russians, a steady stream of reinforcements began arriving on scene, jumping straight into the battle to aid their embattled comrades. After force marching for eight hours straight, General Panyutin and the vanguard of the Army of Wallachia had arrived at Ryakhovo.

By this time, most of the British Army had also converged on Ryakhovo, bringing the two forces to a rough parity once again as much of the Russian 2nd Corps was still absent from the battlefield. With the half of the Russian Army still away from the battlefield, General Brown remained committed to the fight and pressed his men to keep pushing as dusk began to settle over the bloody plain. The fighting would only end as the thick darkness of night descended on the battlefield, resulting in several incidents of friendly fire on both sides. Although total victory had eluded Brown, the possibility still remained for the British to inflict a great blow upon the Russians and drive them from Rumelia.

When dawn broke the following morning, it was Brown and the British who took the offensive yet again, hoping to break through the Russian line before their reinforcements arrived. The battle that followed would be relatively even for much of the day, with a slight edge given to the British owing to their superior rifles and cannons. However, once again Russian reinforcements continued to arrive as the day wore on, turning the tide against the British. No matter their personal valor, nor their great weapons of war, the British were simply being overwhelmed by the sheer number of Russian soldiers facing off against them. No matter how many men they shot down, another would eventually emerge to take their place. Eventually, the unending waves of Russian men began to exhaust the thin red line. As dusk began to fall over the battlefield, General Brown recalled his men and made preparations for a third day of fighting.

The British Advance against the Russians at Ryakhovo

By the end of the second day of Ryakhovo, almost all of the Russian Army of Wallachia had assembled opposite the British, bringing their total strength to nearly 142,000 soldiers. All told, Brown’s Army of 64,000 men was outnumbered by more than 2 to 1. With his opportunity of victory lost, Brown elected to take the defensive on the third day at Ryakhovo; his men would make the Russians pay for every inch of dirt they took. General Panyutin was more than willing to oblige him, ordering a dawn offensive against the weakening British.

As the Russian soldiers approached the British line, the British artillery released a cannonade of grapeshot upon the advancing Russians, ripping their advance echelons to shreds. Entire units were wiped out, while regiments were decimated as mounds of bodies began to litter the battlefield. Within a few brief moments, over 4,000 Russians had fallen to the British artillery and rifle fire. It wasn’t enough as the Russians kept advancing. Eventually, the Russian infantry reached the thin British line and began to inflict their revenge upon their oppressors. The vicious melee that followed would see both sides suffer extensively, but outnumbered as they were, the British were gradually losing ground. At around noon, after five hours of bitter fighting, the Russians finally punched through the British center, forcing General Brown to order a retreat.

General Panyutin was not inclined to let the British flee unmolested, however, and immediately ordered his cavalry to pursue them. As the 1st Uhlan Division and a division of Don Cossacks came into sight, all remaining discipline within the British Army collapsed, leading to a general rout. The Russian horsemen gazed upon the terrified Britons with devilish delight and whipped their ponies into a hellish frenzy. Cutting down stragglers and foolhardy heroes as they went, their trot quickly turned into an all-out charge as they chased the fleeing British soldiers. Desperate to escape the coming cavalry, many Englishmen threw themselves into the Danube, choosing a watery grave to a Cossack's torture.

They are only spared from total annihilation by the sacrifice of the British Heavy Brigade which counter charged the approaching Russian cavalry with a thunderous roar, blunting its attack with a great and awesome fury. For the better part of an hour, the Heavy Brigade fought a bitter war of attrition with the Russian horsemen. Aided by their thick wool coats, their large chargers, and the rather dull weapons and small ponies of their Russian adversaries, the British cavalrymen suffered relatively few casualties initially, while they in turn inflicted gruesome losses on their opponents. It was only when General Panyutin ordered his infantry into the fray that the British cavalry were decimated. With bayonets fixed, the Russian soldiers speared the poor British horses, killing them from underneath their riders and without their steeds, the men of the Heavy Brigade were quickly cut down, bringing an end to the Battle of Ryakhovo.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade

Overall, the battle of Ryakhovo was a decisive Russian victory as the British Army was effectively broken as a threat, losing over a third of its men in the battle with most of their losses coming on the third day of battle. However, this victory had only been won at an enormous cost for the Russians. Over the three days of fighting, nearly 17,800 Russians lay dead or dying, another 41,300 were wounded, and nearly 11,000 were captured or missing. Moreover, the Army of Wallachia’s Cavalry contingent was utterly gutted after their prolonged fight with the British Heavy Brigade, losing more than half their number in the scuffle. Nevertheless, with the British Army finally defeated, the road to Silistra was thrown open and after two days of rest, Panyutin’s Army set out in pursuit late on the 19th of June.

Back in Silistra, the Ottomans met with some moderate success, holding their ground against Count Luder’s Army of Moldavia and even driving it back in some places. However, with the defeat of the British at Ryakhovo, the situation in Silistra was now untenable. Racing ahead of his army, General Brown would meet with Omar Pasha, informing him of his defeat and advising him to immediately abandon Silistra before the Russians surrounded them. Despite his great reluctance to do so, Omar Pasha agreed with the merits of Brown’s suggestion and ordered the evacuation of Silistra. Anything of value in the city was to be destroyed, buried, or carted off by the retreating Anglo-Ottoman Army; they would leave nothing of value to the Russians.

When the British Army finally arrives at Silistra later that evening, they are immediately ordered to destroy their precious railroad, spike their heavier siege guns, and set out for the Balkan Mountains as fast as they were able, from where they would establish a new defensive front. For the next few hours, a great dread hovers over Silistra as the Anglo-Ottoman Army desperately scrambled to vacate the city before the Russians arrived. Fortunately for the Allies, news of Panyutin’s victory over the British at Ryakhovo would prompt excessive celebration within Lüders’ camp. Soldiers and officers alike ate, drank, and sang well into the night, reveling in their comrades’ great victory. They would only awaken late in the morning of the 21st, by which time most of the Allied host had already evacuated Silistra. When the Russian Army finally stirred from its trenches and began moving into Silistra around mid-afternoon, it would discover an abandoned city.

The Fall of Silistra and Ruse would mark the effective end to any remaining Ottoman interest in this terrible war. In their eyes, the war was now completely lost. Their northern and eastern defenses had been captured and their armies had been smashed to pieces. Further resistance at this point would only result in further losses now and further concessions in the ensuing peace treaty. Despite British pleas to continue fighting, no amount of British coin or shipments of British weapons would convince them otherwise. On the 13th of July, Ottoman envoys arrived in the Russian camp outside Silistra requesting a ceasefire, but to their horror, they would learn from Prince Gorchakov that his eminence, Tsar Nicholas was not yet interested in peace. The war would continue.

Next Time: Coalition

[1] The old city of Ercis was steadily submerged by the rising waters of Lake Van over the course of the 18th Century, until it was completely submerged by the middle of the 19th Century.

[2] In OTL, nearly all the original British Division commanders and many of their deputies left the army for home. Some were genuinely sick or wounded like Sir George de Lacy Evans and the Duke of Cambridge, but many simply made-up excuses to leave the Crimea.

[3] The city of Ruse formed a part of the Ottoman Quadrangle, a series of fortress cities comprised of Ruse, Silistra, Shumen and Varna. These fortifications were made at the suggestion of Helmuth von Moltke in OTL and were largely built by local Bulgarians laborers. They were incredibly strong fortifications that even managed to repel the Russians in 1877 for several months, despite being severely outdated by that time.

Russian Cavalrymen Pursue Fleeing Ottoman Soldiers

The start of the 1856 campaigning season would begin a little later than the previous year. Having already fulfilled most of his objectives, and much more, General Nikolay Muravyov would instead allow his exhausted soldiers time to rest and recuperate after a year and a half of almost constant fighting and marching in extremely difficult terrain and weather. Beyond this, however, his dreadfully long supply lines simply made it impossible to keep pushing westward at the rate he had in 1855. Instead, the Russian Army of the Caucasus would be refocused outwards once Spring arrived in Anatolia, expanding its narrow salient to both the North and the South.

In the south, a portion of the Russian Army under Prince Vasily Osipovich Bebutov would successfully reduce the Beyazit salient by the end of May. Resistance in the area had been rather sporadic as the Ottomans had largely evacuated their remaining troops from the region over the Winter. After Beyazit’s fall on the 15th of April, Bebutov was instructed to begin pushing southwards toward Lake Van and then onward to the cities of Mush and Van if possible. However, his offensive here would run into increasing trouble, more so from the rugged terrain and local Kurdish bandits than any official Ottoman resistance. Prince Bebutov’s detachment would eventually reach the northeastern corner of Lake Van by the end of June, near the submerged town of Ercis.[1] However, rather than press onward as originally instructed, Bebutov would receive new orders from St. Petersburg to halt his advance in place and began digging in.

Another Russian detachment under Prince Ivan Andronikashvili would press against Reshid Pasha’s forces stationed in the hills west of Erzincan. His efforts were largely focused on tying down Turkish forces in the region, rather than making a concerted push in any particular direction. Despite this, the general weakness of the Ottoman defenders enabled relatively modest gains for the Russians along this front. Their largest drawbacks were constant supply shortages, which gave the Ottomans a slight advantage in firepower, but overall, the Russians still maintained the edge here. By the end of June, Prince Andronikashvili had managed to reach the outskirts of Gercanis, roughly 18 miles West from where he first started his campaign in April. Even still, he had succeeded in his primary objective, as Reshid Pasha and Selim Pasha were unable to send any significant reinforcements to assist in the defense of the Lazistan or the Van Eyalets.

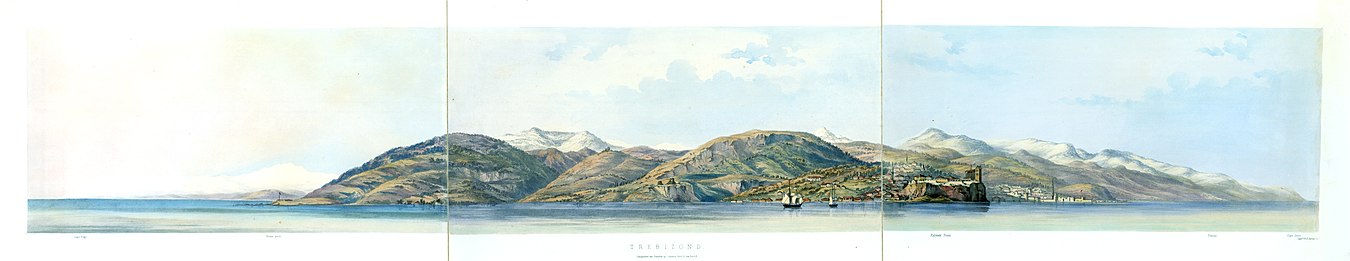

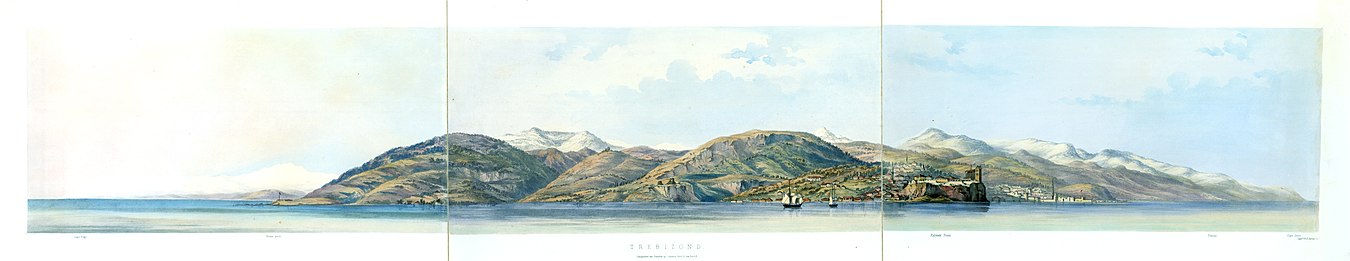

The main Russian objective of the Anatolian front in 1856 was the Pontic coast, however, with the port of Trabzon being of particular importance to St. Petersburg given its status as a prominent commercial hub. As the Porte’s premier Black Seas port, it would provide Russia with great wealth and influence over all trade in the region if captured. The Ottoman commanders in the region recognized Russia’s interest in the port and had used the extended lull in the fighting to fortify the passes through the Pontic Mountains against the coming Russian offensive. But with their shattered armies and dreadful morale, there was little the beleaguered Ottomans could do in the face of the impending Russian juggernaut.

The Port City of Trabzon

Beginning on the 10th of April, General Muravyov took 54,000 men northward and began his assault on the Pontic Coast. Despite significant support from the British Royal Navy and the Ottoman Black Seas Fleet, the port of Batumi would fall within a month’s time. The nearby town of Rize would also come under considerable pressure soon after. Like Batumi before it, Rize would surrender to the Russians after a month-long siege at the end of May. Muravyov’s attempts to take Trabzon, however, would encounter more resistance as the last battered remnants of Mehmed Pasha’s Army along with various British marines and sailors, and a number of Circassian, Crimean, Dagestani, and Lazi irregulars stood against them.

Moreover, the British Royal Navy and Ottoman Black Seas Fleet would position several ships off the coast of Trabzon. Despite the risk from Russian guns on land, the allied ships frequently bombarded the approaching Russian Army, effectively deterring any concentrated attempts to take the city by storm. Similarly, a constant stream of supply ships into and out of Trabzon’s harbor ensured that the city was well provisioned, mitigating the risk of it falling to starvation. Nevertheless, Muravyov was a tenacious general and continued the siege, steadily moving his lines forward, inch by inch over the course of several weeks. By mid-June, the threat to Trabzon was real enough that the British dispatched several regiments from the Balkans to help defend the city despite the perilous situation in Rumelia.

The arrival of these British soldiers in Trabzon would ironically coincide with a decisive shift in priorities by the Russian Government away from the Caucasus and Anatolia. Men and resources previously allocated to the Caucasus Front were now being drawn off to fight in other areas, with entire divisions now being recalled for service in the Balkans, the Baltic and Central Asia. Even General Muravyov was ordered northward to lead the upcoming Fall campaign against the Caucasian Imamate and the Circassian Confederacy. His departing address to his soldiers was brief and blunt, but still a highly emotional event for his soldiers who had come to respect and admire the Old Bear, General Muravyov.

Despite the great success for the Russians on the Anatolian front, it came to a quiet end in early July 1856. Barring Trabzon, all of Russia’s pre-war objectives for this front had been fulfilled and then some after two years of bitter fighting. As such few, if any, in St. Petersburg had the will or the interest to continue investing desperately needed resources into this theater, beyond what was necessary to hold their new gains. Tsar Nicholas was personally against a continued offensive into the increasingly Muslim countryside of Central Anatolia especially when more vital fronts like the Balkans needed further support. In truth, this decision had been made over the Winter; the continued success by Muravyov’s men in the Spring and Summer only quickened this process.

The Anatolian Front in the Summer of 1856

This year’s offensive in the Balkans would begin with another Russian assault on Silistra’s defenses by Count Alexander von Lüders’ Army of Moldavia, supported by General Karl Schilder’s extensive Corps of Artillery. Boasting over 400 cannons (mostly smaller calibers and older vintage guns), the Russian bombardment peppered the Allied lines with fire and iron in preparation for the Russian offensive. The ensuing attack on the 24th of April would be directed against the entirety of the Anglo-Ottoman line, probing it for vulnerabilities and searching for any openings. However, unlike the foolhardy attacks of the year prior, this onslaught would be a meticulous campaign meant to wear down the resolve and the strength of the Allied defenders over time. Although it would cost them a tremendous amount in blood, the Russians had blood enough to spare.

They need not try too hard, however, as the British rank and file were in dismal spirits by the start of 1856. Many of their comrades had died of cholera and typhus over the last year, while many more were sent to Scutari to recuperate or invalidated home before being unceremoniously discharged from the service. Several leading officers would abandon the Army under the guise of illness or injury, while others like the Duke of Cambridge were recalled for political reasons further weakening British morale and discipline.[2] The continuous skirmishing with the Russians over the Winter didn’t help either. Were it not for the stalwart leadership of General Brown, many of his men would have likely mutinied or deserted in the face of the looming Russian attack.

British Soldiers “Celebrating” Another Year in Silistra

Defeatism was also quite rampant in the Turkish ranks as the continuous stream of bad news from Eastern Anatolia poured in over the Fall and Winter, destroying the already fragile Ottoman morale. Similarly, relations with London had soured immensely after they had coerced the Sublime Porte into ceding territory to the Kingdom of Greece. Although, the influx of additional British coin and weapons into the Ottoman Empire would help soothe the ruffled feathers in Constantinople, many of the Ottoman troops along the Danube were now distrustful of their British allies, whom they considered fair weather friends and opportunists. Despite this, many troops in the Ottoman Army remained committed to the war effort if for no other reason to defend their homes and their families. Some were motivated purely by spite, with the Poles largely fighting to injure the Russians after decades of oppression and persecution.

Fortunately, the Allies would receive a desperately needed boost in late April/early May with the arrival of the British 6th Infantry Division - the “Irish Division” - and the British Foreign Legions which would help restore the British Army’s flagging morale and strength. The British Army in the Balkans would in fact top 100,000 soldiers briefly before attrition and redeployments to India reduced it to around 68,000 men. Most of the British reinforcements would be stationed along the Danube front, with most being allocated to the defense of Silistra. A handful of regiments were sent to fortify the ports of Varna and Burgas, and the fortress of Shumen, while a brigade was sent to help defend the river crossings further west. The collapse of the Anatolian front the year prior, would also force General Brown to dispatch a few brigades of the British Foreign Legion eastwards to aid in the defense of Trabzon.

The Ottomans would also call up the garrisons of Thessaly, Epirus, and Serbia for field duty after the recent treaties with Serbia and Greece. Unfortunately, while these men were trained fighters, they were generally second-rate troops who had been relegated to guard duty and police work. They would also receive another 11,000 volunteers from Albania, Bosnia, North Africa, and the Levant, but nearly two thirds were directed to the Anatolian front, providing little assistance to Omar Pasha. Moreover, these men were Bashi-bazouks, undisciplined mobs more interested in plunder and personal glory than victory or strategic gains. Despite their rowdiness, the Porte could not turn these men away when it desperately needed bodies to hold the line against Russia.

Through some miracle, the Anglo-Ottoman lines outside Silistra held against Count Lüders’ attack as they rushed these new arrivals into the fray. In doing so, however, they had fallen for Prince Gorchakov’s trap as Lüders’ offensive was merely the anvil to Gorchakov’s hammer. As this offensive was taking place, Prince Gorchakov dispatched the Russian Army of Wallachia under General Fyodor Sergeevich Panyutin to force additional crossings upriver. General Dannenberg and the Russian 4th Corps would resume their offensive from last year, marching on Silistra from the village of Tutrakan. Simultaneously, the 2nd Reserve Division under General Alexander Adlberberg and the 3rd Reserve Division under General General Wilhelm Bussau would move against the cities of Vidin and Oryakhana respectively. However, General Panyutin’s true hammer blow would fall on the fortress city of Ruse.[3]

The City of Ruse in the early 19th Century

The city of Ruse was a major port along the Danube river, serving as both a prominent trade hub in the region and a crossroads for all traffic going up and down and across the Danube. Most importantly it sat on the road between Bucharest and Constantinople, giving it incredible value to both sides. As a result of its strategic location; Romans/Byzantines, Bulgarians, and Ottomans alike would all invest much into securing this region against any northern aggressors. Under the Ottomans, Ruse developed a thriving shipbuilding industry and quickly became their chief administrative center along the lower stretch of the Danube.

Like Silistra, Varna and Shumen, it had been heavily fortified during the 1830’s and early 1840’s seeing the construction of several polygonal fortresses outside the city’s medieval walls, which were themselves updated and expanded as well. It also boasted a sizeable garrison prior to the war, with two regiments of infantry and a regiment of artillery for a total of 8,000 soldiers. However, the War would see the infantry regiments drawn away to aid in the defense of Silistra, reducing Ruse’s garrison by more than two thirds. Fortunately, the garrison would be reinforced with the arrival of troopers from Thessaly and Serbia along with volunteers from Macedonia and Albania boosting their number well above 5,000 just in time for Russian General Stepan Khrulev’s attack on the 1st of May.

The attack by General Khrulev’s Russian 2nd Corps would meet with some moderate success initially as the Russians quickly reclaimed the Wallachian island of Ciobanu which had been had captured by Omar Pasha at the very start of this War. However, their efforts to reach the walls of Ruse would be repelled after a fierce firefight as the Ottoman garrison released a small fleet of boats and barges to disrupt the Russian crossing here. Eventually, the Russians would cross the river, but here they fell into an Ottoman trap as Ruse's riverside defenses were especially strong, with dozens of cannons and carefully prepared kill-zones which cut the Russian vanguard to ribbons. Unable to make much progress against Ruse, General Khrulev dispatched the 1st Infantry and 2nd Grenadier Divisions to force another crossing further West near the port of Sistova (Svishtov).

Unlike at Ruse, the Russian crossing at Sistova would meet with much more success as the town was only protected by a company of Turkish soldiers stationed at old Tsarnevets castle. As was the case in 1810 and 1829, the Russian soldiers quickly stormed the castle’s medieval walls, brushing aside the undermanned and unprepared Ottoman garrison with relative ease. With a firm beachhead across the Danube now secured, Khrulev released the 1st Uhlan Division to fan out across the countryside, searching for any Turkish pickets on the road to Ruse. When they returned with no such news, Khrulev ordered his Corps across the Danube, leaving the 4th Division behind to screen Ruse from the North. Seven days later on the 15th of May, Khrulev’s Corps would reconverge outside the southern outskirts of Ruse, effectively surrounding it from all sides.

Russian Soldiers crossing the Danube near Ruse

Whilst Ruse’s defenses were quite robust, aided as they were by the swift Danube currents and months of preparation; the city’s garrison was still quite undermanned, numbering only 5,671 men at this point, compared to the nearly 68,000 Russians gathered outside their walls. In spite of these tremendous odds, the Ottoman garrison was able to resist the Russian onslaught for several days. Moreover, Khrulev’s siege lines were not air tight during the first few days of the siege, enabling Ottoman messengers to escape to Silistra.

Word about Ruse’s plight would soon reach the ears of Omar Pasha and General Brown, but given their own dire situation at Silistra, there was little the Allied Commanders could do. They simply lacked the resources to counteract Lüders’ ongoing offensive from the East, Dannenberg’s continued push from the West, and now this maneuver by Khrulev against Ruse. Nevertheless, they endeavored to send whatever help they could to Ruse, but their effort would come too late. With Ruse surrounded, Khrulev steadily chipped away at the Ottoman defenses, until finally, on the 5th of June he released his entire Corps upon the city of Ruse. The defenders fought desperately, but eventually succumbed to the insatiable tide of the Russians, leading to their surrender.

With Ruse’s fall, the Russians had gained a major junction across the Danube, albeit one that was further West than they would have preferred. Nevertheless, its capture provided an alternative to Silistra, enabling the Russians to ferry over large quantities of men and munitions unhindered. It also forced the already beleaguered British and Ottomans to stretch their forces even further to defend their now dangerously exposed western flank, lest Panyutin's Army march on Constantinople unopposed. After a week’s pause to rest his forces, General Khrulev directed his cavalry southward towards Tarnovo and westward against Pleven, inciting the local Bulgarians to revolt as they went.

Several days later, General Panyutin would send word to Khrulev instructing him to travel eastward with his Corps and link up with General Dannenberg’s 4th Corps. Thereafter, they would converge on Silistra from both the West and South, cut its supply lines, and finally surround the city. Unfortunately for Panyutin, a deserter from the Russian camp, believed to be a Polish officer, leaked much of this battleplan to Omar Pasha and General Brown. Although the exact extent of the Russian operation was unknown to them, they recognized that they would be doomed if Panyutin’s Army was allowed to reach Silistra uncontested. Despite the risk, they knew that this was their last chance to force the Russians back. Pinning everything on this next campaign, both Omar Pasha and General Brown opted to march out of Silistra and face the Russians head on.

Ottoman Soldiers Receive their New Orders

The Ottoman Army of Rumelia, under Omar Pasha would sally out against Count Lüders’ Host, holding it in place whilst General Brown’s Balkan Expeditionary Force would march against General Dannenberg’s 4th Corps - which was dangerously exposed - and destroy it before it could rejoin with the rest of Panyutin’s army. Setting out on the 9th of June, Brown’s Army would catch Dannenberg by surprise outside the village of Vitren. In the ensuing battle, the Russian 4th Corps would be thoroughly defeated by the British, but in spite of its extensive losses - losing over a quarter of its men to death, desertion, or capture – Dannenberg’s Corps would manage to retreat in relatively good order. Opting to pursue it, General Brown and the British Army would chase the fleeing 4th Corps for the next four days, fighting a series of skirmishes and minor engagements with the Russian rearguard before finally catching them near the hamlet of Ryakhovo located on the banks of the Danube.

With Dannenberg’s men now trapped between the British Army and the Danube, General Brown hoped to smash them to pieces and then turn his attention to Khrulev’s 2nd Corps. Unfortunately, much of his own army had become strung out across the countryside over the last few days, leaving him with three divisions (1st, 4th, and 6th) to fight against four weakened Russian divisions. Whilst he initially contemplated waiting for the rest of his army to catch up, time was now against him as his scouts reported that Panyutin’s Army of Wallachia had left Ruse and was now marching to Dannenberg’s aid. Spurred on to crush Dannenberg’s weakened Corps before the rest of the Russian Army arrived, General Brown ordered an immediate attack on the Russian position.

Despite their dire predicament, the Russians were in relatively good spirits, and held their ground against the advancing British for several hours. As the day progressed, the fighting grew more desperate as the veteran Highlander Brigade smashed through the thin Russian line in multiple places. While it seemed as if the battle was lost for the Russians, a steady stream of reinforcements began arriving on scene, jumping straight into the battle to aid their embattled comrades. After force marching for eight hours straight, General Panyutin and the vanguard of the Army of Wallachia had arrived at Ryakhovo.

By this time, most of the British Army had also converged on Ryakhovo, bringing the two forces to a rough parity once again as much of the Russian 2nd Corps was still absent from the battlefield. With the half of the Russian Army still away from the battlefield, General Brown remained committed to the fight and pressed his men to keep pushing as dusk began to settle over the bloody plain. The fighting would only end as the thick darkness of night descended on the battlefield, resulting in several incidents of friendly fire on both sides. Although total victory had eluded Brown, the possibility still remained for the British to inflict a great blow upon the Russians and drive them from Rumelia.

When dawn broke the following morning, it was Brown and the British who took the offensive yet again, hoping to break through the Russian line before their reinforcements arrived. The battle that followed would be relatively even for much of the day, with a slight edge given to the British owing to their superior rifles and cannons. However, once again Russian reinforcements continued to arrive as the day wore on, turning the tide against the British. No matter their personal valor, nor their great weapons of war, the British were simply being overwhelmed by the sheer number of Russian soldiers facing off against them. No matter how many men they shot down, another would eventually emerge to take their place. Eventually, the unending waves of Russian men began to exhaust the thin red line. As dusk began to fall over the battlefield, General Brown recalled his men and made preparations for a third day of fighting.

The British Advance against the Russians at Ryakhovo

By the end of the second day of Ryakhovo, almost all of the Russian Army of Wallachia had assembled opposite the British, bringing their total strength to nearly 142,000 soldiers. All told, Brown’s Army of 64,000 men was outnumbered by more than 2 to 1. With his opportunity of victory lost, Brown elected to take the defensive on the third day at Ryakhovo; his men would make the Russians pay for every inch of dirt they took. General Panyutin was more than willing to oblige him, ordering a dawn offensive against the weakening British.

As the Russian soldiers approached the British line, the British artillery released a cannonade of grapeshot upon the advancing Russians, ripping their advance echelons to shreds. Entire units were wiped out, while regiments were decimated as mounds of bodies began to litter the battlefield. Within a few brief moments, over 4,000 Russians had fallen to the British artillery and rifle fire. It wasn’t enough as the Russians kept advancing. Eventually, the Russian infantry reached the thin British line and began to inflict their revenge upon their oppressors. The vicious melee that followed would see both sides suffer extensively, but outnumbered as they were, the British were gradually losing ground. At around noon, after five hours of bitter fighting, the Russians finally punched through the British center, forcing General Brown to order a retreat.

General Panyutin was not inclined to let the British flee unmolested, however, and immediately ordered his cavalry to pursue them. As the 1st Uhlan Division and a division of Don Cossacks came into sight, all remaining discipline within the British Army collapsed, leading to a general rout. The Russian horsemen gazed upon the terrified Britons with devilish delight and whipped their ponies into a hellish frenzy. Cutting down stragglers and foolhardy heroes as they went, their trot quickly turned into an all-out charge as they chased the fleeing British soldiers. Desperate to escape the coming cavalry, many Englishmen threw themselves into the Danube, choosing a watery grave to a Cossack's torture.

They are only spared from total annihilation by the sacrifice of the British Heavy Brigade which counter charged the approaching Russian cavalry with a thunderous roar, blunting its attack with a great and awesome fury. For the better part of an hour, the Heavy Brigade fought a bitter war of attrition with the Russian horsemen. Aided by their thick wool coats, their large chargers, and the rather dull weapons and small ponies of their Russian adversaries, the British cavalrymen suffered relatively few casualties initially, while they in turn inflicted gruesome losses on their opponents. It was only when General Panyutin ordered his infantry into the fray that the British cavalry were decimated. With bayonets fixed, the Russian soldiers speared the poor British horses, killing them from underneath their riders and without their steeds, the men of the Heavy Brigade were quickly cut down, bringing an end to the Battle of Ryakhovo.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade

Overall, the battle of Ryakhovo was a decisive Russian victory as the British Army was effectively broken as a threat, losing over a third of its men in the battle with most of their losses coming on the third day of battle. However, this victory had only been won at an enormous cost for the Russians. Over the three days of fighting, nearly 17,800 Russians lay dead or dying, another 41,300 were wounded, and nearly 11,000 were captured or missing. Moreover, the Army of Wallachia’s Cavalry contingent was utterly gutted after their prolonged fight with the British Heavy Brigade, losing more than half their number in the scuffle. Nevertheless, with the British Army finally defeated, the road to Silistra was thrown open and after two days of rest, Panyutin’s Army set out in pursuit late on the 19th of June.

Back in Silistra, the Ottomans met with some moderate success, holding their ground against Count Luder’s Army of Moldavia and even driving it back in some places. However, with the defeat of the British at Ryakhovo, the situation in Silistra was now untenable. Racing ahead of his army, General Brown would meet with Omar Pasha, informing him of his defeat and advising him to immediately abandon Silistra before the Russians surrounded them. Despite his great reluctance to do so, Omar Pasha agreed with the merits of Brown’s suggestion and ordered the evacuation of Silistra. Anything of value in the city was to be destroyed, buried, or carted off by the retreating Anglo-Ottoman Army; they would leave nothing of value to the Russians.

When the British Army finally arrives at Silistra later that evening, they are immediately ordered to destroy their precious railroad, spike their heavier siege guns, and set out for the Balkan Mountains as fast as they were able, from where they would establish a new defensive front. For the next few hours, a great dread hovers over Silistra as the Anglo-Ottoman Army desperately scrambled to vacate the city before the Russians arrived. Fortunately for the Allies, news of Panyutin’s victory over the British at Ryakhovo would prompt excessive celebration within Lüders’ camp. Soldiers and officers alike ate, drank, and sang well into the night, reveling in their comrades’ great victory. They would only awaken late in the morning of the 21st, by which time most of the Allied host had already evacuated Silistra. When the Russian Army finally stirred from its trenches and began moving into Silistra around mid-afternoon, it would discover an abandoned city.