You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Light at the End of the Tunnel: A TL of the American Railroad

- Thread starter Duke Andrew of Dank

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

ATSF's Plan B: The Rock Island Cut-up ALCO DSL-30: The Passenger Train of the Future Milwaukee Road: The Electric Avenue Passenger Rail in the Barkley Act Russel's Grand Plan Top 5 Passenger Trains in America: 1949 New York Times poll The Trailer Train Makes Its Start; 1949 The Walt Disney SurvivorsJust for the record, any rail-related thing I don't mention ITTL yet can be assumed to be the same as OTL unless I retcon it latter.

I just fixed that.The SP's original route as people point out was one that looped all the way around, and if that can be fixed through new construction that's a benefit not only to the major cities but also to Anaheim, Long Beach, Orange County and all the communities along the coast.

Any ideas for improvements to past posts or future posts?

Just remember that there has not been much in regards to merging railroads yet. That won't come for a while still.

Just remember that there has not been much in regards to merging railroads yet. That won't come for a while still.

The Northeast to Norfolk: Thanks to the Keystone

Under William W. Atterbury, the Pennsylvania Railroad had been working hard to fight the NYC. Aside from a brief illness Atterbury quickly got over in 1935, the Pennsy was working its best to continue its constant contest with the Central. As part of his grand strategy, Atterbury expanded the PRR's ties with the Norfolk & Western, a long-time subsidiary that linked it to Ports and Coal Fields of the Virginias. In addition, the two roads purchased a 35% stake in the Richmond, Fredricksburg, and Potomac, totaling it to 70%. When other stakeholders in the time protested, the two roads responded by expressing a desire for a stronger mainline connection in the east. As well as pointing out the bottleneck that was Potomac Yard in Washington DC.

To the latter end of mitigating the "Potomac Problems", the PRR also proposed extending the RF&P to Norfolk via Chesapeake Bay and Newport News. But this was determined to be too expensive so in August 1936, the RF&P and N&W decided to link themselves better by building a line of their own from Richmond to Petersburg, which would be considered part of the N&W. The PRR also proposed a deal with both the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line to have Richmond be the new interchange point for traffic going to the Northeast. The two southern roads agreed, and it was decided to expand the Acca yard in Richmond tenfold. This worked fruitfully as the yard found itself picking up much of the slack from Potomac Yard, in addition to the N&W becoming a major player in the small, but important role of connecting Norfolk to the Northeast.

Meanwhile, the Norfolk & Western also made an agreement with the Southern Railroad in regards to shuffling various lines around as they were already close through their work with the latter's DC-Tennessee trains. Under the final deal, the Southern helped N&W build a line parallel to theirs from Farmville to Richmond, and sold them the branch to West Point, VA. While in exchange, the Southern's trackage rights over the N&W from Lynchburg to Bristol, TN were expanded to allow the movement of freight to Tennessee. Both the Farmville-Richmond and Richmond-Petersburg lines were finished by August 1938, and was celebrated by a Norfolk-Richmond-Lynchburg-Roanoke excursion. Though the original line to Petersburg was kept for freight movements.

The new trackage would permit the N&W's passenger service to link all three of the major cities in the state of Virginia's southern half: Roanoke, Richmond, and Norfolk. As such, the N&W worked with the PRR to revise the Powhatan Arrow, Cavalier, and other trains to run via Richmond and Petersburg. Then run west on PRR metal to either Chicago or Detroit. This arrangement would continue for the entirety of the pre-Amtrak era of American rail travel. Whereas the Norfolk lines remained longer until Amtrak Northeast built the the bridge-tunnel across Chesapeake Bay.

In celebration of the successes, the PRR and N&W opted to extend the Colonial service, operated jointly with the New York, New Haven, & Hartford, further South. Under this arrangement, an RF&P engine would take over the train from Washington DC to Richmond, with the N&W having an engine take it the rest of the way to Norfolk. To that end, the N&W would go on to streamline several of the K2 class 4-8-2s ubiquitous to their passenger trains at the time. Though these engines would prove good enough to take the northbound train up to Washington at times while RF&P 4-8-4s sometimes hauled the southbound equivalents all the way to Norfolk. In either case, most of the K Series engines were eventually being replaced by the bigger and better J Class 4-8-4s by the Second World War.

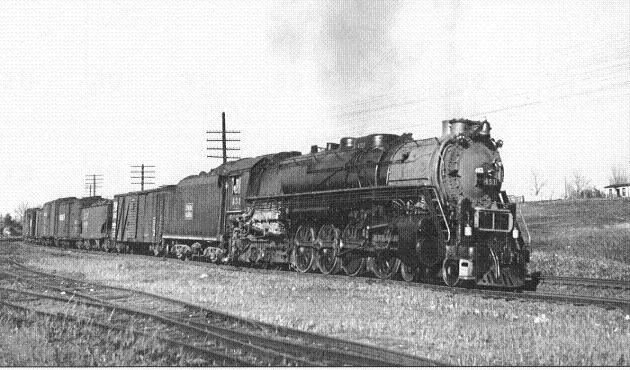

Shortly after the extension of the Northeast Corridor into Virginia in 1938, N&W K2 Mountain #123 is waiting to lead the southbound version of The Colonial from Richmond the rest of the way to Norfolk via Petersburg. Today, its sister #126 is among the engines operated out of the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke.

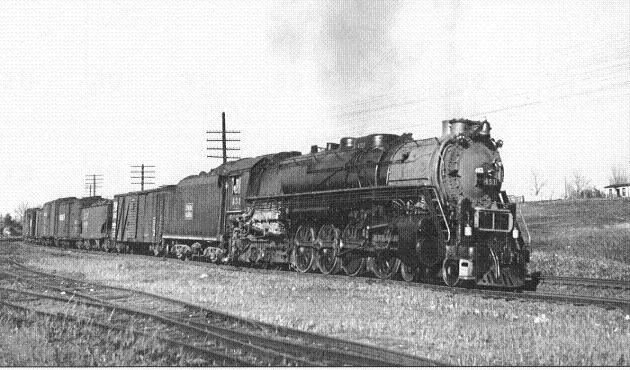

One of the RF&P's War-time Berkshires leads a southbound freight train that was handed over to her at Acca Yard. This freight was most likely picked up from the ACL or SAL, as traffic from N&W would usually go behind one of their own A Class 2-6-6-4 Mallets.

OOC: Special thanks to @TheMann for helping with the brainstorm session for this part of the TL.

To the latter end of mitigating the "Potomac Problems", the PRR also proposed extending the RF&P to Norfolk via Chesapeake Bay and Newport News. But this was determined to be too expensive so in August 1936, the RF&P and N&W decided to link themselves better by building a line of their own from Richmond to Petersburg, which would be considered part of the N&W. The PRR also proposed a deal with both the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line to have Richmond be the new interchange point for traffic going to the Northeast. The two southern roads agreed, and it was decided to expand the Acca yard in Richmond tenfold. This worked fruitfully as the yard found itself picking up much of the slack from Potomac Yard, in addition to the N&W becoming a major player in the small, but important role of connecting Norfolk to the Northeast.

Meanwhile, the Norfolk & Western also made an agreement with the Southern Railroad in regards to shuffling various lines around as they were already close through their work with the latter's DC-Tennessee trains. Under the final deal, the Southern helped N&W build a line parallel to theirs from Farmville to Richmond, and sold them the branch to West Point, VA. While in exchange, the Southern's trackage rights over the N&W from Lynchburg to Bristol, TN were expanded to allow the movement of freight to Tennessee. Both the Farmville-Richmond and Richmond-Petersburg lines were finished by August 1938, and was celebrated by a Norfolk-Richmond-Lynchburg-Roanoke excursion. Though the original line to Petersburg was kept for freight movements.

The new trackage would permit the N&W's passenger service to link all three of the major cities in the state of Virginia's southern half: Roanoke, Richmond, and Norfolk. As such, the N&W worked with the PRR to revise the Powhatan Arrow, Cavalier, and other trains to run via Richmond and Petersburg. Then run west on PRR metal to either Chicago or Detroit. This arrangement would continue for the entirety of the pre-Amtrak era of American rail travel. Whereas the Norfolk lines remained longer until Amtrak Northeast built the the bridge-tunnel across Chesapeake Bay.

In celebration of the successes, the PRR and N&W opted to extend the Colonial service, operated jointly with the New York, New Haven, & Hartford, further South. Under this arrangement, an RF&P engine would take over the train from Washington DC to Richmond, with the N&W having an engine take it the rest of the way to Norfolk. To that end, the N&W would go on to streamline several of the K2 class 4-8-2s ubiquitous to their passenger trains at the time. Though these engines would prove good enough to take the northbound train up to Washington at times while RF&P 4-8-4s sometimes hauled the southbound equivalents all the way to Norfolk. In either case, most of the K Series engines were eventually being replaced by the bigger and better J Class 4-8-4s by the Second World War.

Shortly after the extension of the Northeast Corridor into Virginia in 1938, N&W K2 Mountain #123 is waiting to lead the southbound version of The Colonial from Richmond the rest of the way to Norfolk via Petersburg. Today, its sister #126 is among the engines operated out of the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke.

One of the RF&P's War-time Berkshires leads a southbound freight train that was handed over to her at Acca Yard. This freight was most likely picked up from the ACL or SAL, as traffic from N&W would usually go behind one of their own A Class 2-6-6-4 Mallets.

OOC: Special thanks to @TheMann for helping with the brainstorm session for this part of the TL.

Last edited:

The Streetcar Strikes Again: Pacific Electric's Return to Grace

The Pacific Electric Interurban had long served Los Angeles until the late 1920s, when the railroad became a victim of competition from the automobile. In response, the PE System went to work with the Los Angeles City Council to get subsidies and plans for improvements. Under this proposition, the system would be heavily upgraded to remove street running and get better rolling stock. Then it would try to at least break even with local government help. But instead, the local government voted to take over the line for all this.

In 1930, the plan to restore the system was approved, and the trollies were taken off the streets then run via a series of mainly bridges to the major terminals nearby like near the planned LA Union Station. Much of this was completed by March 1935, and work on many of the principal mainlines would just get their improvements from there. The first actual mainline to be converted such a way was the line from Downtown to Long Beach. This would be achieved more easily then the other lines since it was their first true mainline and did not need as much change. This was around the same time Southern Pacific had begun work on their own line to San Diego. So Pacific Electric made an agreement with said railroad to have their newly grade separated line parallel it for the most part. This part of the line would be completed by Spring 1936. While the SP was working further south to San Diego along the coast on a line parralel to the PE line to Balboa via Huntington Beach, they revised that line in co-operation with SP, and with their financial aid got that job done by October 1936. When the improved line was completed, it ran on 600v and also had received several locomotives for use on the movement of freight cars.

Meanwhile, the American Car Company in St. Louis began to work on a standard type of EMUs for newly built subways or upgrades of streetcars. These would evolve into the new Metro Type Series. By 1934, Pacific Electric purchased more than 250 units for what came the Metro Type I, based loosely on a modified design for the units used on NYC Subway, but with design for wires instead of 3-rail and a more streamlined look. These trains consisted of 4 cars that could coupled up depending on the size of trains. In addition, Pacific Electric took order of the first PCC Streetcars and put them to work on slower services like on places where the ROW hadn't been grade separated yet. These streetcars were proven very useful and soon sent to other interurban companies.

The second part of the big plans would be to separate the Northern Division lines. Again, this was mostly through the use of bridges. But then as they reached areas that were not as populated, there would be parts where the line ran on the ground but was still separated from the road. The line to Burbank was the first to be upgraded in this matter, and was finished by June 1938. Shortly after that, the PE system revised the lines to Beverly Hills via Vineyard with the branch to Hollywood and Lankershim being finished in late 1939. Further work would focus on the Northern Division since it was smaller and there fore less expensive. The initial grade separations were made using a series of tunnels from Downtown to Vineyard, where the line went back to above round and went to either Santa Monica via Beverly Hills or Venice via Culver City. Last for this part of time was the northern division to Al Monte, Azusa, and Pasadena. The upgrades to all three of those places finished in the nick of time as Pearl Harbor happened. So when the fuel was rationed alongside rubber and metal, they were quick to provide service.

Pacific Electric may not have been done at the time, but they still had many tricks up their sleeves as the suburbs grew and the change to upgrade the rest of the system did too. The influence on other major streetcar systems across the nation beginning in 1936 was also profound, and many began or at least drew up plans to make similar improvements. Though relations with Imperial Japan going south, many systems would not get to work on their own upgrades until after the war. Nonetheless, it was clear that even with cars becoming a normal part of American life, the streetcar would prevail.

Sprite Art of one of the Metro Type I trainsets, which were modernized designs for the cars on the New York subway. Pacific Electric bought 250 of the type while improvements were still being finalized, and would serve the company well into the Imperial Electric era of the 1970s.

Sprite Art of one of the Metro Type II trainsets Pacific Electric bought 300 of for their new lines.

Sprite Art of the boxcabs Pacific Electric bought for use on the improved mainlines to shuttle freight cars across the city. Shown here are their forms in the Imperial Electric era from 1947 until their retirement in 1955.

OOC: Special thanks to @isayyo2 and @Lucas for their help, and @TheMann for inspiring some of the content. Lucas especially for the artwork.

In 1930, the plan to restore the system was approved, and the trollies were taken off the streets then run via a series of mainly bridges to the major terminals nearby like near the planned LA Union Station. Much of this was completed by March 1935, and work on many of the principal mainlines would just get their improvements from there. The first actual mainline to be converted such a way was the line from Downtown to Long Beach. This would be achieved more easily then the other lines since it was their first true mainline and did not need as much change. This was around the same time Southern Pacific had begun work on their own line to San Diego. So Pacific Electric made an agreement with said railroad to have their newly grade separated line parallel it for the most part. This part of the line would be completed by Spring 1936. While the SP was working further south to San Diego along the coast on a line parralel to the PE line to Balboa via Huntington Beach, they revised that line in co-operation with SP, and with their financial aid got that job done by October 1936. When the improved line was completed, it ran on 600v and also had received several locomotives for use on the movement of freight cars.

Meanwhile, the American Car Company in St. Louis began to work on a standard type of EMUs for newly built subways or upgrades of streetcars. These would evolve into the new Metro Type Series. By 1934, Pacific Electric purchased more than 250 units for what came the Metro Type I, based loosely on a modified design for the units used on NYC Subway, but with design for wires instead of 3-rail and a more streamlined look. These trains consisted of 4 cars that could coupled up depending on the size of trains. In addition, Pacific Electric took order of the first PCC Streetcars and put them to work on slower services like on places where the ROW hadn't been grade separated yet. These streetcars were proven very useful and soon sent to other interurban companies.

The second part of the big plans would be to separate the Northern Division lines. Again, this was mostly through the use of bridges. But then as they reached areas that were not as populated, there would be parts where the line ran on the ground but was still separated from the road. The line to Burbank was the first to be upgraded in this matter, and was finished by June 1938. Shortly after that, the PE system revised the lines to Beverly Hills via Vineyard with the branch to Hollywood and Lankershim being finished in late 1939. Further work would focus on the Northern Division since it was smaller and there fore less expensive. The initial grade separations were made using a series of tunnels from Downtown to Vineyard, where the line went back to above round and went to either Santa Monica via Beverly Hills or Venice via Culver City. Last for this part of time was the northern division to Al Monte, Azusa, and Pasadena. The upgrades to all three of those places finished in the nick of time as Pearl Harbor happened. So when the fuel was rationed alongside rubber and metal, they were quick to provide service.

Pacific Electric may not have been done at the time, but they still had many tricks up their sleeves as the suburbs grew and the change to upgrade the rest of the system did too. The influence on other major streetcar systems across the nation beginning in 1936 was also profound, and many began or at least drew up plans to make similar improvements. Though relations with Imperial Japan going south, many systems would not get to work on their own upgrades until after the war. Nonetheless, it was clear that even with cars becoming a normal part of American life, the streetcar would prevail.

Sprite Art of one of the Metro Type I trainsets, which were modernized designs for the cars on the New York subway. Pacific Electric bought 250 of the type while improvements were still being finalized, and would serve the company well into the Imperial Electric era of the 1970s.

Sprite Art of one of the Metro Type II trainsets Pacific Electric bought 300 of for their new lines.

Sprite Art of the boxcabs Pacific Electric bought for use on the improved mainlines to shuttle freight cars across the city. Shown here are their forms in the Imperial Electric era from 1947 until their retirement in 1955.

OOC: Special thanks to @isayyo2 and @Lucas for their help, and @TheMann for inspiring some of the content. Lucas especially for the artwork.

Last edited:

The Lake Shore Line: The Chicago Bypass

While Pacific Electric was beginning to prove to Los Angeles that I could and would endure, the interurbans of Chicago made their own plans to stay afloat and even return to service in the case of those abandoned. Three interurbans would take part: The Chicago, Aurora, and Elgin; The South Shore; and the North Shore. Together in 1930, these three interurbans chose to merge their operations into one large mega network to serve the greater Chicago area. With lines spurring out to Aurora to the West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin to the North, and South Bend, Indiana to the east.

But during discussions, the subject of expanding their scope beyond the current lines came to be. There were many interurban lines in the Chicago area that had been abandoned in the past few years. The Chicago & Illinois Valley Railroad was especially eyed for its link to Joliet and other points west. Whereas the Chicago & Interurban Traction Company became a prime target for absorption as a way to serve Kankakee. The plan was all but unanimously approved by the city of Chicago. So it was planned to connect all three of the lines to the Chicago Loop via a four-track mainline running on mostly bridges. Contrary to the tradition of Chicago being where trains terminated, this city would be where they passed through for their further destinations.

This project was completed by October 1935. With the star attraction being Millennium Station, which was once an Illinois Central terminal only. Further east in 1933, work had begun to replace the street running in Michigan City, IN with a bridge or some other improvement. But this was not deemed viable, and so they simply create a strong fence and series of railroad crossings. The final creation of this new South Bend- Milwaukee line was commenced with the introduction of the Michigan Shore. An interurban express from South Bend, Chicago, Milwaukee, and all the major cities in-between.

Then, another idea came up while the board was observing all the major lines they just took up and planned to rebuilt. The Gary Railways Int. had been rebuilt as a second trunk route for South Shore, and expanded until Chicago Heights. While in the north, the North Shore had been expanded from Mundelen in totally new route Carpentensville, and using the new trunk from South Shore, this would be serve like a circular route around Loop and serve the urban sprawl of Chicago metro. That, and it could be possibly let trains from Milwaukee be rerouteed to avoid congestion in downtown.

All the currently planned lines in the Chicago area itself were completed by March 1937. But while observing their new territory, the Lake Shore executives and City of Chicago realized that the Lake Shore could attract heavy freight traffic if they took freight from the western roads like Santa Fe for the Burlington, then took them on a route circumventing the Metro area to places in Indiana where eastern roads like the PRR or Erie would take them further east. The first railroad to give them this chance was the Rock Island. Who agreed to transfer freight to Joliet to take the freight to Valparaiso, Indiana. Which was where Nickel Plate trains often waited to take the freight further east.

In order to serve the planned freight lines, the Lake Shore purchased many of the similar boxcabs to those on the Pacific electric interurban. Whereas the then new Lake Michigan train would be hauled by the Metro Type III train sets. That said, the lack of strong enough freight power for some of the freights did lead to them letting the big roads run the smaller steam engines over a few miles for them to pick up the freight. But then, General Electric came with a better idea. In order to serve the planned freight lines, the Lake Shore purchased many of the similar boxcabs to those on the Pacific electric interurban.

Under this plan, Genera Electric would go on to create the ESV-1000. A medium sized, Bo-Bo electric for lighter freight operations on the mainlines and in the Chicago area and services in the various yards around both there and northwestern Indiana. For passenger service, the Lake Shore introduced the new Lake Shore Liner series of passenger trains. These were powered by the new Metroliner series of passenger EMUs, and could whisk people about anywhere between two major places on the system. Though their main scope was alway the Lake Michigander. A fast service which linked all the major cities between South Bend and Milwaukee in the morning, noon, and evening.

With a few government subsidies and good deals with major roads to bypass the congested terminals in Chicago, the Lake Shore was bound for success. Indeed, by mid 1941 it was one of the busiest lines in the area. What also helped was it lucrative deal with the Belt Railway of Chicago to take freight from their own yards to lighter ones further out.

ESV-1000 was first used for light freight and switching work on the Lake Shore line.

The Milwaukee Road EP-3 was successfully appropriated and improved for many of the larger freights on the Lake Shore.

The Metroliners were fast, reliable, and proud. Making them perfect for the Lake Shore's South Bend-Milwaukee expresses.

OOC: Special thanks to @isayyo2 and @Lucas for their ideas and art.

But during discussions, the subject of expanding their scope beyond the current lines came to be. There were many interurban lines in the Chicago area that had been abandoned in the past few years. The Chicago & Illinois Valley Railroad was especially eyed for its link to Joliet and other points west. Whereas the Chicago & Interurban Traction Company became a prime target for absorption as a way to serve Kankakee. The plan was all but unanimously approved by the city of Chicago. So it was planned to connect all three of the lines to the Chicago Loop via a four-track mainline running on mostly bridges. Contrary to the tradition of Chicago being where trains terminated, this city would be where they passed through for their further destinations.

This project was completed by October 1935. With the star attraction being Millennium Station, which was once an Illinois Central terminal only. Further east in 1933, work had begun to replace the street running in Michigan City, IN with a bridge or some other improvement. But this was not deemed viable, and so they simply create a strong fence and series of railroad crossings. The final creation of this new South Bend- Milwaukee line was commenced with the introduction of the Michigan Shore. An interurban express from South Bend, Chicago, Milwaukee, and all the major cities in-between.

Then, another idea came up while the board was observing all the major lines they just took up and planned to rebuilt. The Gary Railways Int. had been rebuilt as a second trunk route for South Shore, and expanded until Chicago Heights. While in the north, the North Shore had been expanded from Mundelen in totally new route Carpentensville, and using the new trunk from South Shore, this would be serve like a circular route around Loop and serve the urban sprawl of Chicago metro. That, and it could be possibly let trains from Milwaukee be rerouteed to avoid congestion in downtown.

All the currently planned lines in the Chicago area itself were completed by March 1937. But while observing their new territory, the Lake Shore executives and City of Chicago realized that the Lake Shore could attract heavy freight traffic if they took freight from the western roads like Santa Fe for the Burlington, then took them on a route circumventing the Metro area to places in Indiana where eastern roads like the PRR or Erie would take them further east. The first railroad to give them this chance was the Rock Island. Who agreed to transfer freight to Joliet to take the freight to Valparaiso, Indiana. Which was where Nickel Plate trains often waited to take the freight further east.

In order to serve the planned freight lines, the Lake Shore purchased many of the similar boxcabs to those on the Pacific electric interurban. Whereas the then new Lake Michigan train would be hauled by the Metro Type III train sets. That said, the lack of strong enough freight power for some of the freights did lead to them letting the big roads run the smaller steam engines over a few miles for them to pick up the freight. But then, General Electric came with a better idea. In order to serve the planned freight lines, the Lake Shore purchased many of the similar boxcabs to those on the Pacific electric interurban.

Under this plan, Genera Electric would go on to create the ESV-1000. A medium sized, Bo-Bo electric for lighter freight operations on the mainlines and in the Chicago area and services in the various yards around both there and northwestern Indiana. For passenger service, the Lake Shore introduced the new Lake Shore Liner series of passenger trains. These were powered by the new Metroliner series of passenger EMUs, and could whisk people about anywhere between two major places on the system. Though their main scope was alway the Lake Michigander. A fast service which linked all the major cities between South Bend and Milwaukee in the morning, noon, and evening.

With a few government subsidies and good deals with major roads to bypass the congested terminals in Chicago, the Lake Shore was bound for success. Indeed, by mid 1941 it was one of the busiest lines in the area. What also helped was it lucrative deal with the Belt Railway of Chicago to take freight from their own yards to lighter ones further out.

ESV-1000 was first used for light freight and switching work on the Lake Shore line.

The Milwaukee Road EP-3 was successfully appropriated and improved for many of the larger freights on the Lake Shore.

The Metroliners were fast, reliable, and proud. Making them perfect for the Lake Shore's South Bend-Milwaukee expresses.

OOC: Special thanks to @isayyo2 and @Lucas for their ideas and art.

Last edited:

And for better visualization, this is the Lake Shore network by 30s. @Andrew Boyd @isayyo2

Attachments

In the 6th paragraph there's a sentence or two that come twice.

Great to see a map

Consolidating all the interurban in a region like that and building some missing links to create a better whole is a great idea. By the 21st century that could have changed the way the city works fundamentally, if zoning allows it.

Great to see a map

Consolidating all the interurban in a region like that and building some missing links to create a better whole is a great idea. By the 21st century that could have changed the way the city works fundamentally, if zoning allows it.

Will the Electric Railroads Presidents Conference still convene a Committee and develop the Presidents' Conference Committee (PCC) Steetcar?

For those unfamiliar, it was a standard design that was incredibly adaptable. The ERPCC collected royalties on the cars that St. Louis Car Co., Pullman-Standard and Canadian Car and Foundry built. Changes from previous orders from the major car builders led to a block of changes between pre and postwar cars: different windows and windshields with a 12° slant changing to 30°, change from electropneumatic doors and to straight electric. Most postwar cars have 2 rows of windows, an easy way to spot them.

There are so many variations that there was no truly zero-option standard cars, but the base configuration was 46' long x 8'6" wide, drivers' position at one end, double width front and centre doors.

Some cars had minor differences, others major- Cincinnati cars had two trolley poles side-by-side, Kansas City postwar cars had prewar windows, and other minor changes.

Here are some examples:

Philadelphia (standard):

Toronto (couplers and wired for multiple unit operation on some examples; followed by a secondhand Cleveland car which also had a forced-draft ventilation system):

Washington DC (shortened):

Chicago (lengthened, extra triple rear door):

Pacific Electric (Los Angeles) (lengthened, MU-able, double ended):

Newark (ex-Twin Cities) (widened, retrofitted with pantograph):

Boston (Standard length, MU-able, left hand side doors for high centre platforms):

Shaker Heights (Cleveland suburb) (Lengthened, widened, MU-capable, left hand side doors for ground level centre platforms):

For those unfamiliar, it was a standard design that was incredibly adaptable. The ERPCC collected royalties on the cars that St. Louis Car Co., Pullman-Standard and Canadian Car and Foundry built. Changes from previous orders from the major car builders led to a block of changes between pre and postwar cars: different windows and windshields with a 12° slant changing to 30°, change from electropneumatic doors and to straight electric. Most postwar cars have 2 rows of windows, an easy way to spot them.

There are so many variations that there was no truly zero-option standard cars, but the base configuration was 46' long x 8'6" wide, drivers' position at one end, double width front and centre doors.

Some cars had minor differences, others major- Cincinnati cars had two trolley poles side-by-side, Kansas City postwar cars had prewar windows, and other minor changes.

Here are some examples:

Philadelphia (standard):

Toronto (couplers and wired for multiple unit operation on some examples; followed by a secondhand Cleveland car which also had a forced-draft ventilation system):

Washington DC (shortened):

Chicago (lengthened, extra triple rear door):

Pacific Electric (Los Angeles) (lengthened, MU-able, double ended):

Newark (ex-Twin Cities) (widened, retrofitted with pantograph):

Boston (Standard length, MU-able, left hand side doors for high centre platforms):

Shaker Heights (Cleveland suburb) (Lengthened, widened, MU-capable, left hand side doors for ground level centre platforms):

Last edited:

That's not to say it won't be in the future.First thought was, that new Penn Station wasn't canon? #@&$+

Just added that in passing to TTL's Pacific Electric.Will the Electric Railroads Presidents Conference still convene a Committee and develop the Presidents' Conference Committee (PCC) Steetcar?

A Day of Infamy: December 7, 1941

A moment of silence for the fallen and a stark reminder:

Freedom is not free.

The Last of the Pre-War steamers

1942 was the last year the railroads were allowed to design steam engines from scratch, as restriction used to conserve time mandated using pre-existing designs 1943 onwards. As well as the onslaught of Lima's fleet of Standardized designs railroads could easily buy from. To distinguish them from those built after the mandate, these engines were known as Late Bloomers, while those built in the war were called War Babies.

The CP Royal Hudson, which the FSF-1 basically was, albeit with new paint and smoke deflectors.

Union Pacific FSF-1 Class 4-6-4

- Built by ALCO

- Numbered 700-743

- Built from design for Canadian Pacific Royal Hudsons.

- Painted in scheme based on that of Challenger Streamliner.

- Operated in the Northwest of the UP system.

Union Pacific 4884-1 Class 4-8-8-4

- Built by ALCO

- Numbered 4000-4024

- Better known as the "Big Boy"

- Built for heavy freight through the Wasatch Mountains.

- #4014 still operated by UP on excursions.

Chesapeake & Ohio L-2 Class 4-6-4

- Built by Baldwin

- Numbered 300-307, 310-314

- Operated on level ground with passenger trains.

- One, #312, on display at the Lima Locomotive Works Museum.

Louisville & Nashville M-1 Class 2-8-4

- Built by Baldwin and Lima

- Numbered 1950-1991

- Called "Big Emmas"

- The designers included every improvement and feature known to the steam locomotive builder's craft.

- Built for freight service.

- Two survive, #1966 in the Southeastern Railway Museum in Duluth, GA; and #1985 at the Kentucky Railway Museum in New Haven, KY.

The RF&P 4-8-4s were used as the basis of the L&N N-1 due to being smaller than the ACL R-1s.

Louisville & Nashville N-1 Class 4-8-4

- Built by Baldwin and Lima

- Numbered 2000-2025

- Called "Big Nellies"

- Designed from the 4-8-4s of the RF&P, but with elements of the M-1

- Built for passenger service on the improved mainline from New Orleans to either Cincinnati or Chicago via the C&EI.

- One survives, #2010 at Evansville, IN, under restoration.

Southern Pacific GS-4/GS-5 Class 4-8-4

- Built by Lima

- Numbered 4430-4457; 4458, 4459

- Built for the Daylight trains and other major SP services.

- One survives, #4449 on excursions for SP. #4458 on display at Golden Gate Railroad Museum.

Southern Pacific AC-10/AC-11 Class 4-8-8-2

- Built by Baldwin

- Numbered 4205–4244; 4245–4274

- Built for heavy freights especially in the Sierra Nevada.

- #4274 on display in Los Angeles.

The Chesapeake & Ohio T-1 Texas type was one of the two main inspirations for the J1. With the other being the R3 class 4-8-4, which it shared many parts with.

Pennsylvania Railroad J1 Class 2-10-4

- Built by Lima, Baldwin, and Juniata

- Numbered 6150–6174, 6401–6500

- Built as a freight equivalent of the R3 4-8-4 "Keystone", and shared many components like the boilers.

- #6150 survives as one of the many PRR engines in the RR Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg.

OOC: Special Thanks to @TheMann for letting me use the UP 4-6-4 idea.

The CP Royal Hudson, which the FSF-1 basically was, albeit with new paint and smoke deflectors.

Union Pacific FSF-1 Class 4-6-4

- Built by ALCO

- Numbered 700-743

- Built from design for Canadian Pacific Royal Hudsons.

- Painted in scheme based on that of Challenger Streamliner.

- Operated in the Northwest of the UP system.

Union Pacific 4884-1 Class 4-8-8-4

- Built by ALCO

- Numbered 4000-4024

- Better known as the "Big Boy"

- Built for heavy freight through the Wasatch Mountains.

- #4014 still operated by UP on excursions.

Chesapeake & Ohio L-2 Class 4-6-4

- Built by Baldwin

- Numbered 300-307, 310-314

- Operated on level ground with passenger trains.

- One, #312, on display at the Lima Locomotive Works Museum.

Louisville & Nashville M-1 Class 2-8-4

- Built by Baldwin and Lima

- Numbered 1950-1991

- Called "Big Emmas"

- The designers included every improvement and feature known to the steam locomotive builder's craft.

- Built for freight service.

- Two survive, #1966 in the Southeastern Railway Museum in Duluth, GA; and #1985 at the Kentucky Railway Museum in New Haven, KY.

The RF&P 4-8-4s were used as the basis of the L&N N-1 due to being smaller than the ACL R-1s.

Louisville & Nashville N-1 Class 4-8-4

- Built by Baldwin and Lima

- Numbered 2000-2025

- Called "Big Nellies"

- Designed from the 4-8-4s of the RF&P, but with elements of the M-1

- Built for passenger service on the improved mainline from New Orleans to either Cincinnati or Chicago via the C&EI.

- One survives, #2010 at Evansville, IN, under restoration.

Southern Pacific GS-4/GS-5 Class 4-8-4

- Built by Lima

- Numbered 4430-4457; 4458, 4459

- Built for the Daylight trains and other major SP services.

- One survives, #4449 on excursions for SP. #4458 on display at Golden Gate Railroad Museum.

Southern Pacific AC-10/AC-11 Class 4-8-8-2

- Built by Baldwin

- Numbered 4205–4244; 4245–4274

- Built for heavy freights especially in the Sierra Nevada.

- #4274 on display in Los Angeles.

The Chesapeake & Ohio T-1 Texas type was one of the two main inspirations for the J1. With the other being the R3 class 4-8-4, which it shared many parts with.

Pennsylvania Railroad J1 Class 2-10-4

- Built by Lima, Baldwin, and Juniata

- Numbered 6150–6174, 6401–6500

- Built as a freight equivalent of the R3 4-8-4 "Keystone", and shared many components like the boilers.

- #6150 survives as one of the many PRR engines in the RR Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg.

OOC: Special Thanks to @TheMann for letting me use the UP 4-6-4 idea.

Last edited:

The beginning of long distance electrification.What do you guys want to see next?

The beginning of long distance electrification.

This alongside universal agreement of high speed signaling equipment and track improvements either in the New Deal era or Mann's Transport America program.

Plus early containerization if possible.

I'm afraid that the war already began, so I'll have that in mind for after VJ day.The beginning of long distance electrification.

Steamin' It Up: The First and Most Famous of The Lima Standards

As the diesel locomotive began to emerge as a major force in modern railroad power, the Lima Locomotive Works decided that they had best work on trying to stay relevant. In a study conducted, it was decided that Lima should standardize their locomotive designs as far as they could. What helped at the time was that when it became clear the US may enter the Second World War as an Allied Power, most railroads were faced with the need to flog whatever equipment they had on them to the upmost limit. Many soon realized that this would call for whatever new engines they could get their hands on.

Then, a major game changer came in the form of French designer Andre Chapelon. Having come from his home country early in the Nazi occupation, he saw America as an excellent place to try his hand at applying his ideas. Lima agreed to interviewed him, and were impressed with his ideas for widely using roller bearings, Kylchap exhaust system, enlarged steam passages, enclosed cabs, mechanical stoker or oil burning, and 300 psi boiler. Lima was impressed with many of his ideas, though they did remind him that other than the need to use pre-existing designs for the engines, his ideas would mostly be accepted. Chapelon didn't mind too much, and quickly set to work. In the end, he decided on modeling the engines after various USRA designs. As well as Lima's own designs for the Chesapeake & Ohio. That said, he was able to create relatively new design or two under his rule. Though the restrictions of the time prevented his addition of Belpaire Fireboxes on many engines as he would have liked.

In addition, the idea was that these engines could be fitted with certain kinds of tenders depending on the fuel needs of the railroads. Including 12-wheel ones like those for Western Maryland 2-8-0s and 2-10-0s, and the largest being 16-wheel ones based on the tenders used by the Pennsylvania Railroad R3 4-8-4s and J1 2-10-4s.

MK-F Class 2-8-2s

An HO Scale model of a Western Maryland MK-F, classified as the "N" Class. Admittedly, it's rather inaccurate due to mostly using the toolings of a normal USRA Light Mikado, not to mention the tender not being the WM 12-wheelers.

The first engine to be built was MK-F #001, which was designed off the USRA Mikado with several modifications by Chapelon. Such as roller bearings, Kylchap exhaust system, and mechanical stokers. At first, the engine was tested on various railroads but was not widely accepted. However the engine was eventually tested on the Western Maryland, who almost immediately took a liking to the engine. Eventually ordering 25 of the type for fast freight from Connelsville, PA to Baltimore and classified them as the "N" Class. The success of the MK-F on the "Wild Mary" was eventually recognized by the Norfolk & Western who ordered several of them for use in Ohio on local freight work, referring to them as the "T" Class engines.

BK-F Class 2-8-4s

Nickel Plate #765, today one of the nation's most iconic steam excursion stars, was built as a variant of one of the Lima Wartime BK-Fs.

However, Lima soon saw that most railroads were looking for large engines to haul the war loads. This was especially true in the eastern part of the rail network, where before the largest common engine was the 4-8-2 Mountain type. As was exemplified by the Baltimore & Ohio T-3s, Pennsylvania M1s, and others. However, the War Board demanded that these engines be used primarily for freight. So Lima selected the Nickel Plate S-1 Berkshire as the engine to use for this purpose, and using Chapelon's Exhaust system, built many for all the major Van Seringen roads like NKP, C&O, and the Erie. However, many also went to the Baltimore & Ohio, where they were used to shuttle freight through the Alleghannies and across the Midwest; typically in places to big for engines like the later EM-1 Yellowstones. In addition, a version with Belpaire Fireboxes were built of Canadian National and the Pennsylvania, the former of whom had previously worked with Lima on rebuilding several 2-8-0s into Berkshires in the 1930s.

NT-D Class 4-8-4s

Central of Georgia's NT-Ds were called the K Class of "Big Apples" and were known for the eight-wheeled tenders. The class leader, #451, is today in operational service and is based out of Macon, Georgia.

Eventually, mixed-traffic engines were determined to be planned for possible requests. With the first of these being the NT-D 4-8-4; a mixed-traffic machine designed from the Southern Pacific GS-2s. The first engine to request these was the Central of Georgia Railroad, which had found itself in need of a larger passenger engine. Soon, they could be seen plying all across the Peach State with both freight and passenger trains. These engines were so successful that further examples were ordered by the CofG's parent company Illinois Central for use on their secondary Chicago - New Orleans trains. While another 10 were bought up by the Erie Railroad for their Erie Limited. However, the use of them as mere mixed-traffic engines meant that railroads further west generally did not see much use for them; not even Southern Pacific saw a need for them to be built.

CS-F Class 2-8-0s and DC-F Class 2-10-0s

Only one USATC S160 stayed in the UK after 1944, and it was never painted in a BR livery. Not that it ever stopped the preservationists.

One of the USATC S250s, which was sent to Poland where it was classified the TyK246. The biggest differences from the original DC-F and original S250s, beyond the bufferbeam and headlight, are designs for the tender and the cab.

Two of the most famous Lima Santadards however would be the CS-F Class 2-8-0 and DC-F Class 2-10-0. These engines were initially built by Lima for use by the Chicago, Indianapolis, & Louisville for fast, heavy freight service on their main line, and were also planned to be ordered by the Louisville & Nashville and Burlington Route. However, the design would eventually explode in fame when the US Army Transportation Corps requested several engines for use as war machines. Eventually classified the S160 and S250, these two engines would find themselves in various nations on the European Continent after the war. As well as running in other nations like China, Korea, and Southern Africa [2].

Other projects

In addition to all these engines, Lima also allowed various railroads to send their steamers to be upgraded with the Kylchap Exhuast System. Eventually virtually all the Pennsylvania Railroad's engines were fitted with this system, as were many of the larger steam engines on the Union Pacific's roster such as the FEF series 4-8-4s and the FSF Hudsons designed from Canadian Pacific Royal Hudsons. The system would eventually be applied again with the Union Pacific's FEF-4 series built jointly between by ALCO and Lima.

[1] Thanks to @TheMann for letting me use his CN 2-8-4 idea.

[2] ITTL, railroads in Southern Africa are 4ft 8.5 in gauge, as opposed to OTL's 3ft 6in gauge.

Then, a major game changer came in the form of French designer Andre Chapelon. Having come from his home country early in the Nazi occupation, he saw America as an excellent place to try his hand at applying his ideas. Lima agreed to interviewed him, and were impressed with his ideas for widely using roller bearings, Kylchap exhaust system, enlarged steam passages, enclosed cabs, mechanical stoker or oil burning, and 300 psi boiler. Lima was impressed with many of his ideas, though they did remind him that other than the need to use pre-existing designs for the engines, his ideas would mostly be accepted. Chapelon didn't mind too much, and quickly set to work. In the end, he decided on modeling the engines after various USRA designs. As well as Lima's own designs for the Chesapeake & Ohio. That said, he was able to create relatively new design or two under his rule. Though the restrictions of the time prevented his addition of Belpaire Fireboxes on many engines as he would have liked.

In addition, the idea was that these engines could be fitted with certain kinds of tenders depending on the fuel needs of the railroads. Including 12-wheel ones like those for Western Maryland 2-8-0s and 2-10-0s, and the largest being 16-wheel ones based on the tenders used by the Pennsylvania Railroad R3 4-8-4s and J1 2-10-4s.

MK-F Class 2-8-2s

An HO Scale model of a Western Maryland MK-F, classified as the "N" Class. Admittedly, it's rather inaccurate due to mostly using the toolings of a normal USRA Light Mikado, not to mention the tender not being the WM 12-wheelers.

The first engine to be built was MK-F #001, which was designed off the USRA Mikado with several modifications by Chapelon. Such as roller bearings, Kylchap exhaust system, and mechanical stokers. At first, the engine was tested on various railroads but was not widely accepted. However the engine was eventually tested on the Western Maryland, who almost immediately took a liking to the engine. Eventually ordering 25 of the type for fast freight from Connelsville, PA to Baltimore and classified them as the "N" Class. The success of the MK-F on the "Wild Mary" was eventually recognized by the Norfolk & Western who ordered several of them for use in Ohio on local freight work, referring to them as the "T" Class engines.

BK-F Class 2-8-4s

Nickel Plate #765, today one of the nation's most iconic steam excursion stars, was built as a variant of one of the Lima Wartime BK-Fs.

However, Lima soon saw that most railroads were looking for large engines to haul the war loads. This was especially true in the eastern part of the rail network, where before the largest common engine was the 4-8-2 Mountain type. As was exemplified by the Baltimore & Ohio T-3s, Pennsylvania M1s, and others. However, the War Board demanded that these engines be used primarily for freight. So Lima selected the Nickel Plate S-1 Berkshire as the engine to use for this purpose, and using Chapelon's Exhaust system, built many for all the major Van Seringen roads like NKP, C&O, and the Erie. However, many also went to the Baltimore & Ohio, where they were used to shuttle freight through the Alleghannies and across the Midwest; typically in places to big for engines like the later EM-1 Yellowstones. In addition, a version with Belpaire Fireboxes were built of Canadian National and the Pennsylvania, the former of whom had previously worked with Lima on rebuilding several 2-8-0s into Berkshires in the 1930s.

NT-D Class 4-8-4s

Central of Georgia's NT-Ds were called the K Class of "Big Apples" and were known for the eight-wheeled tenders. The class leader, #451, is today in operational service and is based out of Macon, Georgia.

Eventually, mixed-traffic engines were determined to be planned for possible requests. With the first of these being the NT-D 4-8-4; a mixed-traffic machine designed from the Southern Pacific GS-2s. The first engine to request these was the Central of Georgia Railroad, which had found itself in need of a larger passenger engine. Soon, they could be seen plying all across the Peach State with both freight and passenger trains. These engines were so successful that further examples were ordered by the CofG's parent company Illinois Central for use on their secondary Chicago - New Orleans trains. While another 10 were bought up by the Erie Railroad for their Erie Limited. However, the use of them as mere mixed-traffic engines meant that railroads further west generally did not see much use for them; not even Southern Pacific saw a need for them to be built.

CS-F Class 2-8-0s and DC-F Class 2-10-0s

Only one USATC S160 stayed in the UK after 1944, and it was never painted in a BR livery. Not that it ever stopped the preservationists.

One of the USATC S250s, which was sent to Poland where it was classified the TyK246. The biggest differences from the original DC-F and original S250s, beyond the bufferbeam and headlight, are designs for the tender and the cab.

Two of the most famous Lima Santadards however would be the CS-F Class 2-8-0 and DC-F Class 2-10-0. These engines were initially built by Lima for use by the Chicago, Indianapolis, & Louisville for fast, heavy freight service on their main line, and were also planned to be ordered by the Louisville & Nashville and Burlington Route. However, the design would eventually explode in fame when the US Army Transportation Corps requested several engines for use as war machines. Eventually classified the S160 and S250, these two engines would find themselves in various nations on the European Continent after the war. As well as running in other nations like China, Korea, and Southern Africa [2].

Other projects

In addition to all these engines, Lima also allowed various railroads to send their steamers to be upgraded with the Kylchap Exhuast System. Eventually virtually all the Pennsylvania Railroad's engines were fitted with this system, as were many of the larger steam engines on the Union Pacific's roster such as the FEF series 4-8-4s and the FSF Hudsons designed from Canadian Pacific Royal Hudsons. The system would eventually be applied again with the Union Pacific's FEF-4 series built jointly between by ALCO and Lima.

[1] Thanks to @TheMann for letting me use his CN 2-8-4 idea.

[2] ITTL, railroads in Southern Africa are 4ft 8.5 in gauge, as opposed to OTL's 3ft 6in gauge.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

ATSF's Plan B: The Rock Island Cut-up ALCO DSL-30: The Passenger Train of the Future Milwaukee Road: The Electric Avenue Passenger Rail in the Barkley Act Russel's Grand Plan Top 5 Passenger Trains in America: 1949 New York Times poll The Trailer Train Makes Its Start; 1949 The Walt Disney Survivors

Share: