Lands of Red and Gold #79: Burning Mouth, Burning Rocks

“This is a land of burning ground. The people dig up rocks and burn them. Even what grows from the ground burns your mouth.”

- From a Yigutji traveller’s account, after visiting the Kuyal [Hunter Valley, NSW] during the fourteenth century.

* * *

History may be written by the victors, but only if they have a tradition of writing history in the first place.

The art of writing history is not an advanced practice in Aururia. In so far as it has developed, it is practised most frequently by the peoples of the Five Rivers [Murray-Darling basin], the ancient heart of Aururian agriculture and still overall the most economically productive part of the continent.

Before their contact with the Raw Men from beyond the known world, historians of the Five Rivers – and their peoples generally – viewed only four political entities as being properly civilized. These were the “four states” [1]: the three kingdoms of the Five Rivers themselves, namely Tjibarr, Gutjanal and Yigutji, and the Yadji Empire.

The Five Rivers historians regarded every other people on the continent as being primitive, barbaric, or disorganised, or some combination of the three. The Atjuntja of the far west were viewed as barbaric, the Nangu of the Island were regarded as too disorganised to count as a state, while the Kurnawal kingdom of the Cider Isle [Tasmania] was regarded as primitive.

In their categorisation of the rest of the continent, Five Rivers historians held particularly low opinions of the eastern coast. They viewed the cultures there as having achieved the trifecta of primitivism, barbarism and disorganisation.

Of course, Five Rivers historiography, such as it was, took no account of geography or biogeography. Farming did not develop on the eastern coast; all of the founding crops for Aururian agriculture were found west of the continental divide, in the Five Rivers. In addition to the great ranges of the continental divide acting as a barrier to the first farmers, the terrain on the eastern seaboard is generally more rugged, divided into a few farmable areas which are also difficult to travel between even when moving north and south. The rivers of the eastern coast are short and usually unnavigable, in stark contrast to the rivers which supported early transportation and commerce in the west.

Together, these factors meant that agriculture was slower to get established in the east, and that societies there were more fragmented, with a much lower population density. There were more distinct languages spoken amongst east coast farmers than in all of the other agricultural peoples combined, despite the lower population.

With no beasts of burden other than the dog, and the general geographical barriers, there was only slow transmission of ideas and innovations across the mountains or even between eastern cultures. Writing spread only slowly to the eastern coast, and while there were a few instances of traded iron tools, no eastern culture had adopted meaningful iron working in the pre-Houtmanian era.

Regardless of these reasons, the Five Rivers peoples held a low view of easterners. “

If not for spices, there would be nothing worthwhile in coming to the sunrise lands,” as one traveller wrote, epitomising westerners’ view of the eastern peoples.

Spices, of course, were a very big exception. All Aururian farming societies used spices to some degree, and in many cases those spices could be grown locally. The Five Rivers states cultivated a great variety of herbs and spices, including some such as white ginger and sweet sarsaparilla which were originally native to the eastern seaboard.

The most valuable spices, though, were grown only on the eastern coast. Indeed, their value was high

because they only could be grown in the east, particularly in the more northerly parts of the eastern coast. The higher rainfall, the lack of frost for some frost-sensitive species, and in some cases just natural rarity, limited those spices to the eastern fringes of the continent.

Six main spices grown on the eastern coast commanded interest from westerners. This includes the aromatic leaves of four related trees which another history would call myrtles, but which allohistorical Europeans would name verbenas: lemon, cinnamon, aniseed and curry verbenas. Some of the verbenas had restricted natural ranges, but their value as spices saw them spread along much of the eastern coast, even when they could not be grown inland.

The fifth spice was strawberry gum, another leaf spice [2] whose flavours were used to improve food or

ganyu (yam wine). The sixth eastern coast spice was one which later Europeans would call purple (sweet) peppers, because of the colour of their fruit. While other kinds of sweet peppers were ubiquitous across the farming regions of Aururia, purple peppers were more drought-sensitive and very restricted in their natural range. They were still sought out as trade goods because purple peppers provided the most intense flavour of any Aururian peppers [3].

While spices were cultivated in most eastern coast societies where the climate was warm enough, two regions were particularly prominent for their spices. One was the kingdom of Daluming [around Coffs Harbour], which was close to the ancient sources of tin, and had long been connected to those old trade routes, so forming one of the eastern ends of the Spice Road.

The other region was the River Kuyal [Hunter River]. The Kuyal is one of the longer rivers on the east coast, and its valley has some of the most fertile soils on the continent. The river itself is suitable for transportation along much of its length, although the river mouth has treacherous sandbars which make access difficult for oceangoing vessels. The Kuyal Valley has a decently well-watered climate by Aururian standards, and is the southernmost region that is warm enough to grow the eastern spices. Around the headwaters of the Kuyal, the western mountains are low and easily crossed in several places, which permitted easier trade with the west than for most other eastern coast societies.

These qualities made the Kuyal Valley the other main eastern end of the Spice Road.

* * *

The history of agriculture in the Kuyal began around 500 BC. In that era, the time of the Great Migrations, Gunnagalic-speaking [4] farmers originally from the Nyalananga [Murray] basin were expanding across the continent, driven by drought and warfare to seek out new lands.

Thanks to the ease of crossing the mountains, the Kuyal Valley was one of the first eastern coast regions to be settled by the migrating farmers. The rich soils of the Kuyal were well-suited to the farmers’ crops, and their population expanded rapidly after they established themselves. The previous hunter-gatherer inhabitants were absorbed, leaving only a small genetic contribution to the later inhabitants, providing a few new words to the farmers’ language, mostly place names, and a predilection for gathering certain wild plants, particularly sweet peppers.

The people who inhabited the Kuyal Valley came to call themselves the Patjimunra. As with all the other migrants, they inherited much from their Gunnagalic forebears: a complex system of perennial agriculture, the social system of kinship groups called

kitjigal, and common heritage of religion with deities and associated myths. And in common with the other migrants, that legacy developed in its own direction in the new lands the Patjimunra had occupied.

Unlike other eastern coast peoples, however, the Patjimunra were less isolated from the westerners. The ease of crossing the mountains at the head of their valley, together with the desire for the spices which they had long traded west, made the Patjimunra a target for conquest during the days when the western societies were united into one empire. One of the most ambitious and successful imperial generals, named Weemiraga, conducted his great March to the Sea in 821-822 AD, conquering what were then the Patjimunra city-states. They were the only eastern coast people to be formal tributaries of the Watjubaga Empire.

As per normal practice for tributaries, imperial rule over the Patjimunra largely consisted of demanding tribute from the Patjimunra city-states, and maintaining the peace between them. The Empire maintained two garrisons, whose role was largely to collect the tribute and be a deterrent for potential revolt or warfare between city-states. Governance was largely left to the city-states themselves, with only occasional “advice” from the military governors. Tribute was mostly paid in spices sent back to the imperial heartland.

True imperial rule over the Patjimunra endured for barely half a century. In 872 the Kuyal flooded prodigiously, devastating crops over a wide region, and the city-kings pled poverty rather than pay tribute that year. They used the same excuse the following year, with less credibility, but this too was largely accepted. From that time on, the Patjimunra mainly sent excuses rather than tribute. Imperial rule had been weakened by a devastating civil war in the 850s and a failed conquest of the Kurnawal [in Gippsland, Victoria] in the 860s, so there was little imperial interest in stirring up a fresh revolt.

The already-vague imperial authority was further weakened by another failed conquest in the 880s, when an attempted second march to the sea to conquer the Bungudjimay was defeated, and then by a disputed imperial succession in the 890s. Emboldened by this, and after two and a half decades of paying little tribute, the Patjimunra states issued a joint declaration in 899 that they would no longer pay any tribute. The Empire was in no condition to reassert its authority, and withdrew its garrisons. With other pressing military problems, and since the Patjimunra were perfectly willing to sell spices at reasonable prices, the Empire never attempted a reconquest.

From this point on, the Patjimunra developed largely on their own.

* * *

In the early Gunnagalic farmers, the elaborate social system of the

kitjigal, or skin groups, dominated interpersonal relationships. The ancestral Gunnagal divided themselves into eight kinship groupings (

kitjigal), with all members of the same

kitjigal being considered related. Membership of a

kitjigal changed over the generations in a complex pattern. Elaborate rules covered marriage, inheritance, and other individual and political relationships, based on the

kitjigal. Each of the eight

kitjigal had their own associated colours and totem animals [5].

The Patjimunra inherited the system of

kitjigal, but it evolved a new name and new functions in their land. The old pattern of the

kitjigal was based on a sense of interrelatedness because of the generational change in membership, and it was egalitarian in that no

kitjigal was considered innately superior to any other.

During the settlement of the Kuyal Valley, and the absorption of the previous inhabitants, a new pattern emerged for the

kitjigal. They became gradually linked to occupations, more than interpersonal relationships. In this new system, the pattern of generational change became unacceptable, because the more common expectation was that children would take up the occupations of their parents.

So the old system changed into an occupational-based code. This still dictated rules of intermarriage and inheritance, but now intermarriage was expected to be within a

kitjigal, rather than requiring intermarriage with other groups. Inheritance also followed within the same group. The old code had dictated rules of social interaction where members of certain

kitjigal would avoid certain others; in the new Patjimunra occupational-based code, this morphed into a hierarchy of groups where those which were ranked too far apart would not interact with each other.

The code which developed amongst the Patjimunra originally had some flexibility in moving between groups, but it gradually became more rigid. By the post-imperial era, the code had settled into what future anthropologists would call its “mature form”: a rigid social structure which defined all interactions between people in Patjimunra society.

In the mature form, Patjimunra society was divided into five

ginihi –a word which literally means “skin”, but which will usually be translated as “caste”. Future students of Gunnagalic studies will find the

ginhi to be invaluable when seeking to reconstruct the ancient system of the

kitjigal. The name itself is a linguistic descendant of the Proto-Gunnagalic word for skin. The names of the

ginhi are equally instructive: in three cases, the names are clearly linguistic descendants of the proto-Gunnagalic words for colours (green, gold and blue), while the Patjimunra dialects have adopted unrelated words to replace those missing colours. The names from the remaining two

ginhi are likewise descended from the proto-Gunnagalic words for kinds of animals (brusthtail possums and gray kangaroos) which were totems for two other

kitjigal (red and gray, respectively), and again the Patjimunra words for those two animals are unrelated to proto-Gunnagalic roots. The three remaining

kitjigal have vanished, presumably lost during the migrations or integrated into other ginhi over the centuries.

The five

ginhi are:

(i)

Dhanbang [Greens]. This is the “noble” caste of rulers, warriors, administrators, and secular teachers. They believe they are the highest caste.

(ii)

Warraghang [Golds]. This is the “spiritual” caste. This is the smallest caste and mostly involves priests, spiritual teachers, doctors and advocates, plus a few smaller occupations which are considered spiritually related, e.g. hunting big animals (but not trapping or fishing) and raising ducks (which are considered sacred). They also believe they are the highest caste.

(iii)

Baluga [Blues]. This is the “agricultural” caste. This involves farmers, hunters and trappers of small game, and those who wild-gather some foods (such as berries, other fruits, and spices) or manage woodlands (e.g. when coppicing wood, or loggers). It also involves a few related urban pursuits such as selling “unprepared” food (e.g. eggs, fruit). This is generally viewed as the lowest caste.

(iv)

Paabay [Grays / gray kangaroo]. This is the “service providers / common craftsman” caste. This involves most labourers and town dwellers, house workers and servants, anyone who digs for a living (except coal miners), fishers and sellers of fish, boat-builders, making and selling prepared foods (e.g. bakers), leather workers, millers, and other occupations which are considered common crafts. It also includes a couple of distinctive subcastes: merchants, which to the Patjimunra means anyone who travels to trade; and a group of transient workers / rural labourers who follow seasonal work (e.g. fruit picking, pruning) or short-term urban labouring duties, but who do not permanently own agricultural land. This is generally viewed as the second lowest caste, although sometimes the transient worker subcaste is viewed as lower than the agricultural caste.

(v)

Gidhay [Reds / brushtail possum]. This is the “higher craftsman / non-physical worker” caste. This is a smaller caste which pursues a range of occupations which are seen as higher status than common crafts. It includes scribes and related occupations that require literacy but are not performed by nobles or priests. It includes bronzesmiths, jewellers and any other workers with metal, carpenters, stone masons, and a few other specialty occupations. It also includes anyone who works with coal, including mining and transportation. This is generally believed to be ranked third highest (or third lowest) among the castes.

Movement between

ginhi, including intermarriage, was theoretically forbidden in the post-imperial Patjimunra society. In practice the

ginhi were never completely closed, with a few people managing to move between castes, or more commonly between subcastes, but this became increasingly rare. The Warraghang (priests) were the most strictly concerned with social movement, and cases of people moving into or out of that caste were almost unknown. The most flexibility was between the so-called lower castes of Baluga (agriculturalists) and Paabay (service providers), where intermarriage or even just a new job opportunity would sometimes allow movement.

Patjimunra customs imposed a wide range of requirements and prohibitions on the various

ginhi. For instance, literacy was notionally required for the two upper castes, permitted for the Gidhay (higher craftsmen), and prohibited for the lower two castes. In practice this was sometimes circumvented by the lower castes, especially merchants, while plenty of warrior Dhanbang would struggle to recognise more than their own name in writing.

Bearing arms was something which was permitted only to nobles and priests. This rule was somewhat more strictly enforced, although in practice a weapon was defined as being a metal weapon. So swords, long knives and metal-headed spears were forbidden to the lower three castes. Wooden weapons such as staves were not affected by the prohibition, and even bows were known among the lower castes.

The rules for

ginhi also regulated contact between the different social classes. In general, this meant that contact between the different castes was more restricted with greater distance between them in the hierarchy, and that any interaction which did take place would be within the strictures of the system. For example, contact between the Warraghang (priests) and the three lower castes was acceptable in the context of visiting a temple during services or festivals, or for the Plirite minority when they were visiting for spiritual counsel, but social contact outside of those prescribed roles was not acceptable. The priests and nobles generally had the most interaction of any two castes, due to their mutual belief that they are of the highest rank, but even then social contact was usually limited.

Similarly, the strictures of

ginhi also imposed physical separation between the castes. They generally lived within different districts within the cities, and for the Baluga (agriculturalists) even living within a city was discouraged, except for those subcastes which had urban occupations. Even when some lower castes were required to live in the same dwellings as the higher castes, such as servants, there were strictly demarcated areas within dwellings that the servants lived in during their (usually very limited) non-working time.

The complex rules of

ginhi also affected how they viewed outsiders. Anyone who was not a Patjimunra was viewed as

gwiginhi (skinless) and outside of the proper social system. The usual Patjimunra practice was to deal with outsiders when required, such as merchants trading for spices or warriors conducting raids, but otherwise to have limited engagement with them. Social interaction with the skinless was not forbidden, but largely discouraged outside of the usual hospitality offered to guests. Intermarriage was strictly forbidden, and while it sometimes happened despite this, this almost always meant a Patjimunra who left their lands for the marriage. Having outsiders marry into the local

ginhi was forbidden, and any illegitimate children produced were spurned.

This view of outsiders led to the near-legendary insularity that they displayed when they came into contact with other societies. The Patjimunra happily traded their spices to anyone who came to buy them. In exchange, their most preferred commodity was

kunduri from the Five Rivers, and tin or bronze from both the Cider Isle and the northern highlands [6]. They also valued the dyes, perfumes and resins of the Five Rivers, and the gold of the Yadji and Cider Isle. But while they took these commodities, they remained an inward-looking people who cared little for what happened beyond their borders.

Despite this thriving spice trade with the westerners that had been ongoing for many centuries, and more recent seaborne trade with the Nangu and Maori, the Patjimunra remained resolutely uninterested in the wider world. Very few non-merchants ventured out of their homeland, and rarely did the Patjimunra adopt any new technology or other learning from outside. Matters among the skinless simply held little interest for them. For instance, they remained bronze workers and had never acquainted themselves with iron working. The Nangu, more persistent than most, had some success in spreading their Plirite faith, but even there the Patjimunra adapted it to their own society.

* * *

As with their social structure, the Patjimunra religion developed from their ancient Gunnagalic heritage, but it has been adapted to their new homeland. The old Gunnagalic mythology included a considerable number of beings of power and associated tales about them. The Patjimunra have translated this into a celestial pantheon of twelve deities, the six greater and six lesser gods, each of whom has their representatives among the priestly caste.

The Patjimunra deities are viewed as paired; each greater god has their counterpart among the lesser. Broadly speaking, the greater gods are seen as more distant and forces of nature, with the lesser gods being more concerned with the affairs of men [7].

The twelve deities are:

(I) Water Mother (greater). In ancient Gunnagalic mythology this referred to the deity who was the Nyalananga (River Murray). Among the Patjimunra, this name has been transferred to a goddess who dwells within the waters of the Kuyal and its tributaries. With the frequent, prodigious flooding of this river system, the Water Mother is seen as powerful and often detached from human affairs: her waters bring both life and death with equal indifference.

(i) Crow / The Winged God (lesser). This god is seen as the most cunning and unpredictable of all deities. He is mercurial in his moods, rarely dwelling in one place for long, and often meddling with human affairs. Fickle in his attention, he often plays tricks on people, though sometimes he rewards them too. Many of Crow’s associated tales describe him playing tricks on those who are seen as lacking in virtue, particularly those who are too proud or lack generosity. Some tales say that it was the Winged God who first stole the secret of fire from the Fire Brothers and taught it to men [8], although other tales credit the Sisters of Hearth and Home for the same feat.

(II(a) and II(b)) Fire Brothers (greater). The Fire Brothers are twin gods which represent the creative and destructive aspects of fire: destruction from what is fed to fire, and creation from the regrowth after fires have passed. The Patjimunra view these as two halves of the one whole deity.

(ii(a) and ii(b)) Sisters of Hearth and Home (lesser). These goddesses are viewed as maintaining the fires which are used for cooking and heat, and by extension for all aspects of life within houses. The names of the sisters are descended from two unrelated beings in traditional Gunnagalic mythology, but they have been twinned together in the Patjimunra religion, perhaps to balance the Fire Brothers.

(III) Green Lady (greater). The wandering creator of life from the soil. She is viewed as responsible for the vitality of all plant life, and in a land where even the best-watered lands can experience drought or soil infertility, she is pictured as a wanderer who moves where she wills regardless of human concerns.

(iii) Man of Bark (lesser). The personification of trees, the source of all the goodness that comes from in wattleseeds, wattle gum, the soil replenishing characteristics of wattle farming, and more broadly associated with all forms of timber and nuts. The patron of construction and of transportation; the latter is because of his association with the development of timber boats and travois which are used to move goods.

(IV) Lord of Lightning (greater). The ruler of storms, bringer of thunder and (obviously) lightning. This god is seen as a distant force whose storms can wreak havoc, and who follows his own whims in how he brings them. He is also, more paradoxically, seen as the patron deity of coal, which the Patjimunra believe to be lightning which has been trapped within the earth.

(iv) Windy (lesser). The goddess of wind and (non-stormy) rain. She is viewed as more benevolent than the Lord of Lightning, bringing nourishing rain to the land, but also capable of being angered and withholding rains or sending punishing winds, particularly those that fan bushfires.

(V) Nameless Queen (greater). She who must not be named, lest speaking her name invoke her presence. The collector of souls. The queen of death.

(v) The Weaver (lesser). The judge of the dead, the arbiter of fate. This god is also known by the euphemism of the White God, a name which developed because of the association of a white (blank) tapestry before he wove the fates of men into it in colour. This deity is also more generally associated with law and justice; advocates swear to be faithful to the White God.

(VI) Rainbow Serpent (greater). The shaper of the earth, driver up of mountains, carver of gullies, punisher of wrongdoers, and patron of healing. He is sometimes described as the creator of all. In ancient Gunnagalic mythology, the Rainbow Serpent was also associated with bringing rain, but in the Patjimunra pantheon that role has been taken by other deities.

(vi) Eagle (lesser). The Eagle is seen as watching over all the world, seeing all and knowing all. This is symbolised (naturally) by the wedge-tailed eagle (

Aquila audax) which flies everywhere; while most of the ancient totemic connections to animals have been lost among the Patjimunra, they still see eagles as sacred. Travellers often invoke the Eagle for her guidance and protection on their journey (sometimes together with the Man of Bark). Scholars and teachers also see themselves as guided by the Eagle.

Each of the twelve deities has their own associated myths, practices, and duties for their priests to perform. In most cases, there are also festivals and other services held in the deity’s honour, which the people are expected to attend. Apart from priests (and advocates, who are also of the priestly caste), most Patjimunra do not regard a particular deity as their patron, and will attend ceremonies for most deities, as time permits.

Religion in Patjimunra society is being slowly changed by the spread of Plirism. This new faith has been spread by the Islanders who come in trade, speaking of their religion as they visit. So far only a small number (less than 10%) of the population has converted, and further growth is slow.

Most converts do not abandon their old faith entirely; rather, they integrate Plirism into their existing religious practices. They still view themselves as members of the same castes, and usually attend many of the same celebrations and ceremonies as their old religion. The converts tend to identify their old gods with the related figures in the Islanders’ Plirite traditions. A few Warraghang (priests) have adopted Plirism, and they provide the counselling and guidance that other Plirite priests do in other societies.

The spread of Plirism, and to a lesser degree the increasing contact with outsiders, has brought some minor change to Patjimunra society. Some converts are discontent with the old religion and its strictures, and have advocated more substantial change. So far, this has mostly been manifested in more Patjimunra trying to change occupations, and occasionally being successful, together with some other Patjimunra who have left on Islander ships or over the western mountains.

* * *

The Kuyal Valley has more natural resources than just fertile soils. Beneath the ground, and sometimes right at the surface, is an abundance of what the Patjimunra call “the black rock that burns.” Coal was so abundant and prominent in the valley that the first Europeans to visit the land in another history would name it the Coal River [9].

Somewhere back in the lost mists of prehistory, some early Patjimunra discovered the flammable properties of the black rock. Perhaps they were trying to use the traditional “hot rocks” method of cooking, and discovered that the black rocks got rather hotter than expected.

However they managed it, the early Patjimunra learned the flammable qualities of coal. At first, they held it to be a sacred rock. The earliest archaeological traces of coal usage will be associated with funeral pyres; high-ranking Patjimunra nobles were cremated on fires fuelled (at least in part) by coal. The practice became more widespread amongst members of the nobles and priestly castes, until it was the norm for them to be cremated. The lower castes continued to be buried rather than burned.

Over the centuries, the practice of cremating the dead was abandoned. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, coal became used for other purposes. Bronze workers used coal to fuel their forges, while the wealthy used coal to heat their homes in winter. While timber and charcoal could be used for these purposes, coal was better-suited for metallurgy, and required less use of valuable land than the production of charcoal. Other Aururian civilizations used elaborate systems of coppicing and charcoal production to provide sufficient quantities of fuel, but the Patjimunra used their timber for construction instead, and increasingly relied on coal for fuel.

The first workers of coal were able simply to pick the coal from the ground, thanks to the suitable surface desposits. Because it did not require digging (a lower-caste occupation), and because the black rock was sacred, working with coal came to be considered a higher-caste occupation. The distinction remains, with coal miners and workers being viewed as Gidhay (higher craftsmen), even though the work now involves digging for coal.

When the surface deposits of coal were largely exhausted, the Patjimunra turned to mining. Their mining techniques were not particularly advanced. The Patjimunra mostly used drift mining where they followed surface seams of coal horizontally further into the rock, or some small-scale shaft mining where they dug downward for coal. The main problem was drainage, since they had only very basic pumping methods to remove water. Patjimunra coal mining was thus limited to those locations where the water table was low, or conducting the mining during times of drought. Flooding of mines required long periods of pumping and waiting for the water to subside before they could resume extracting coal.

Despite the limits of their mining technology, coal is abundant enough in the Kuyal Valley that the Patjimunra now use it in considerable quantities for heating and fuel, particularly in metallurgy.

* * *

Agriculture in the Kuyal Valley involves many of the ancestral crops developed by westerners, but some of their cuisine now features some other distinctive crops, either native to their own region or imported from elsewhere than the Five Rivers.

On the east coast, the annual rainfall was much higher than in the natural homeland for their ancestral crops, and the soils were often less well-drained. This sometimes created difficulties when cultivating the traditional staple root crops, such as red yams and murnong, which could rot or yield more poorly in imperfectly-drained soils. Such problems did not occur every year or in every place, but they were frequent enough in some regions that the early Patjimunra adopted additional crops.

In the lower reaches of the Kuyal, flooding was particularly frequent and severe, and many soils remained waterlogged afterward. In these conditions, the earliest Patjimunra farmers often turned to gathering some plants, usually ones which they had been taught about by the previous hunter-gatherer inhabitants. For the best of these plants, they continued to gather them in later years, especially during flood years.

The result was the adoption of the only native Aururian domesticated cereal: a plant which they called weeping grass, and which another history would call weeping rice (

Microlaena stipoides). Weeping grass is a perennial cereal which provides a reasonable grain yield over a wide range of conditions, and is much more tolerant of waterlogged soils than root crops, although it requires more water [10].

The Patjimunra cultivate weeping grass in the most flood-prone and poorly-drained soils, particularly in the lower reaches of the Kuyal. It is only rarely grown elsewhere, since away from waterways the soil usually drains well enough for the higher-yielding red yams to be cultivated. The rainfall is also lower in the upper reaches of the Kuyal, and so the plant is only rarely grown there. Weeping grass has spread to some neighbouring areas of the east coast, but its cultivation has not spread further west.

The Patjimunra are also starting to make more extensive use of a plant which they know as kumara (sweet potato), which they adopted from the Maori. Kumara requires much more rainfall than the red yam, but it also yields highly, so use of this crop is still expanding in the Patjimunra lands.

The Kuyal valley was also the site of another key domestication: the plant which the Patjimunra named jeeree [11]. This is a small tree whose leaves can be used to make a lemony tea. The Patjimunra long ago acquired a taste for this hot drink, which they considered calming (it has a very mild sedative effect), and it has been integrated into their culture. The practice of drinking jeeree spread along much of the east coast, and even to a couple of peoples in southern Aururia, but it has never become commonplace in the Five Rivers, whose inhabitants prefer other beverages such as

ganyu (spiced yam wine). However, the first English visitor to Patjimunra lands, William Baffin, was effusive in his praises of jeeree.

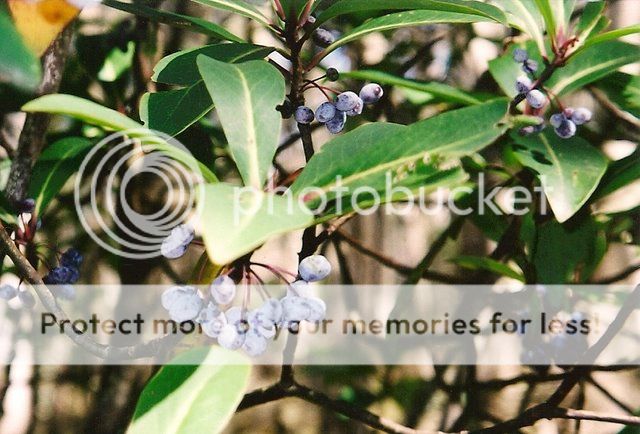

Of all the plants which the Patjimunra cultivate, though, none is more distinctive to their cuisine than this plant:

Europeans will come to call this plant purple sweet pepper. Historically called purple pepperbush or broad-leaved pepperbush (

Tasmannia purpurascens), this plant has the most intense flavour of any Aururian sweet pepper.

In its native range, the purple sweet pepper is found only in two small subalpine areas in the upper reaches of the Kuyal Valley. These areas are both relatively cool (being subalpine), and extremely well-watered. Cultivation of the purple sweet pepper was more difficult than other sweet peppers because of its extremely high water requirements. To the Patjimunra, though, the heat and flavour provided by this plant were highly desirable; enough to make it worth obtaining despite the difficulties.

Early Patjimunra settlers wild-harvested the purple sweet pepper, a practice they adopted from their hunter-gatherer predecessors. In time, they mastered the practice of cultivating it using collected rainwater or irrigation systems. While it remains a finicky plant, the Patjimunra make extensive use of both its stronger berries and milder leaves in their cuisine, which has a reputation for being the hottest in the known world [12]. The dried berries of the purple sweet pepper also make for of their more valuable export spices.

* * *

The Patjimunra live almost exclusively in the Kuyal Valley [Hunter Valley], together with the neighbouring coastal regions. Their largest city is Gogarra [Newcastle, NSW], at the mouth of the Kuyal; the city is the largest simply because their relatively primitive nautical technology makes it much easier to bring food and trade goods downriver rather than upriver, and so that city benefits the most. The largest other cities along the Kuyal are Wonnhuar [Raymond Terrace], Kinhung [Maitland], and Awaki [Whittingham]. Guringi [Denman] is the westernmost town of any size, and is the start of the main overland trade roads with the Five Rivers. All of the cities and towns along the Kuyal have strong city walls, which are used as much for flood control as for defence.

The Patjimunra have also settled some of the neighbouring coast both north and south of their riverine homeland. To the north, their territory stretches to a northerly harbour which they call Torimi [Port Stephens, NSW], although they also use this name for the main city built on the shores of the harbour [Corlette / Salamander Bay]. To the south, they have settled around most of the northern shore of the great saltwater lake that they call the Flat Sea [Lake Macquarie]; their largest city there is Enabba [Toronto]. The Patjimunra previously lived around more of the lake, but their southernmost outpost at Ghulimba [Morriset / Dora Creek] has recently been settled by the Malarri people from further south.

In their political organisation, the Patjimunra were long a people of competing chiefdoms and city-states. They remained in that condition until the imperial conquest in the early ninth century AD. The example of centralised imperial rule offered some inspiration to the more ambitious Patjimunra kings, and following the expulsion of imperial forces in 899, several monarchs sought to unify the Patjimunra. These initial efforts largely failed, but more ambitious monarchs did not stop trying.

Eventually the first unified monarchy was proclaimed under Yapupara, King of the Skin. He claimed all of Patjimunra-settled territory, and even a little beyond in some regions around the Flat Sea. During his lifetime, he even exercised power over those regions.

Unfortunately, the successors to the King of the Skin were often unable to impose similar authority. The Kings of the Skin have continued to rule from Gogarra, but the amount of power they exercise has waxed and waned over the centuries. War, revolution, or a series of natural disasters (floods or earthquakes) is often enough to break the people’s trust in the ruler, and to claim independence. The priestly caste is particularly prone to decrying the authority of a King of the Skin of whom they disapprove, and this sometimes leads to rebellion.

In 1635, on the eve of their first contact with Europeans, most of the Patjimunra were united once more under the rule of the King of the Skin. This included all of the Patjimunra living along the Kuyal itself. Three traditional Patjimunra territories remained outside of the rule of the king at Gogarra. The wealthy city-state of Torimi in the north had maintained independence since 1582. The upland city-state of Gwalimbal [Wollombi] had been independent for even longer, since 1557. What had been the traditional Patjimunra city-state of Ghulimba had been independent of the King of the Skin’s rule since 1602. However, the swelling-fever (mumps) epidemic which swept through the eastern coast during the late 1620s caused much disruption and in some cases movements of people who had abandoned their own lands. One such displaced group of people, the Malarri, invaded Ghulimba in 1630 and claimed rulership of it. The town is now nearly half non-Patjimunra.

In their relations with the wider world, the Patjimunra remain inward-looking. They have traded with the skinless for many centuries, but are still uninterested in the wider world. They trade with the Maori, the Nangu and the Five Rivers, and will be equally accepting of Europeans who come to trade. But they care nothing for what those peoples do in their own lands, except for any territorial disputes with their immediate neighbours.

Of course, no matter how much the Patjimunra refuse to look outward, that will not stop other people looking at them.

* * *

“These pepper trees grow so well, and their sweet peppers sell so well. It is as if we are planting money!”

- Anonymous Breton farmer, 1702

* * *

[1] The Gunnagal phrase which is usually translated as “four states” may also, depending on the ideological views of the author, be translated as “four nations”.

[2] In modern culinary usage, “herb” refers to using the leaves of plants for flavouring, while “spice” refers to any other part of plants, such as seeds, fruit, roots or bark. In allohistorical usage, this distinction is confused because many of the Aururian spices made from leaves resemble flavours that in other parts of the world come from spices, such as cinnamon, aniseed, and pepper. The Aururian products will still be classified as spices.

[3] This represents a small retcon in that the purple pepperbush (

Tasmannia purpurascens) had previously been referred to as having been spread west via trade. After further review of its extremely high moisture requirements and very limited natural range, this has now been changed to having purple pepperbush cultivated only within the *Hunter Valley.

[4] Gunnagalic is the term which allohistorical linguists use for the whole language family descended from that spoken by the first agriculturalists along the Nyalananga; the reconstructed founding language is called Proto-Gunnagal. The name is actually taken from the most commonly-spoken language (Gunnagal) along the Nyalananga at the time of European contact in the seventeenth century, but applied to the whole linguistic family.

[5] See

post #5 for more information about the

kitjigal.

[6] The northern highlands, historically called the Northern Tablelands or New England tableland, is a large highland area in historical north-eastern New South Wales. In Aururia, this was the main ancient source of tin, and a small-scale producer of gold, diamonds and sapphires. The gold and gems are now mostly worked out, although it remains a significant tin-producing region. The northern highlands are mostly divided into warring chiefdoms and city-states, although the Daluming kingdom has recently conquered part of the south-eastern area around *Armidale.

[7] The original Patjimunra words which are translated as “greater” and “lesser”, or alternatively “elder” and “younger”, do not have a connotation of different

power among the deities, or of any hierarchy, but of differences in

focus. The greater gods are those that look at a broader range of things, and so do not look so much at humans in particular, while the lesser gods are those who look more closely at humans but do not do as much for the broader natural world.

[8] Variants of this tale about Crow bringing fire are widespread among various historical Aboriginal peoples.

[9] Much as a prominent rocky headland was called Circular Head, and towns in gem-mining areas were named Emerald, Sapphire, and Rubyvale. Depending on your perspective, this shows either a strong practical bent when naming locations, or just a profound lack of imagination.

[10] Weeping grass is a cereal which has been recently domesticated in modern Australia, where it is marketed as “alpine rice”. Despite the name, it occurs naturally in a wide range of conditions, in both highlands and lowlands. In modern Australia, it also serves a dual purpose because once the grains have been harvested, the plant can be used as a grazing crop. The natural range requires rainfall of about 600mm or higher.

[11] Jeeree, historically known as lemon-scented tea tree (

Leptospermum petersonii), has a flavour which is reminiscent of lemon, but lacks the tartness.

[12] And, if anything, more heat would be welcomed. When the Patjimunra come into contact with the chilli pepper, they will become it as much as rifle-carrying soldiers welcomed the machine gun [13].

[13] Provided those soldiers were behind the machine gun, and not in front of it.

* * *

Thoughts?