Chapter XXI - Jackson Consolidates Power. The Period of National Reorganization

“It gives me great displeasure to announce to the loyal parts of this Congress that the American experiment has, to this day, been set back through failure by failure, which have undone all which the few great founding fathers of this country seeked to accomplish when drafting the initial Constitution three score ago. Nowhere has any consummation of lofty ideals been able to be accomplished, due to the abomination that is our current Constitution.

The consequences of this period of chaos and anarchy has brought great peril to our great State. All pecuniary advantages possibly achieved during this period have been lost to the States, which used their misgranted freedoms to rebel against our legitimate rule. The danger I have so warned before, of cultural conflict and strife between good folk and Indians and freed slaves has come to fruition, on a war that has laid waste to our land and our people. Rapidly, our population, wealth and power has dwindled to nothingness; it is a sad fact that today many hope to leave our land and go south, to lands that are under the domain of Papists and Indians. This is but logical, after so many years of misrule - what good man would prefer the current country of the Whig and the Indian, one covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages, only relieved by a half dozen cities, crowded and filled with foreign men with foreign tongues? When have we lost the goal of our noble Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by happy white families, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?

This is why the current status quo must come to an end. We must devise a new method of governance - one not encumbered by the Southron wish of rebellion or the Yankee wish of amassing wealth, one not encumbered by a misguided ploy of making equals out of unequals.

I announce that, as of today, the country must enter a Period of National Reorganization. The current Constitution is null and void; I shall rule with temporary decrees until order is reestablished under our proper, God-mandated system. The Congress, infiltrated with traitors and thieves, must be shuttered until new elections can be administered; the States must be purged of all traitorous elements.”

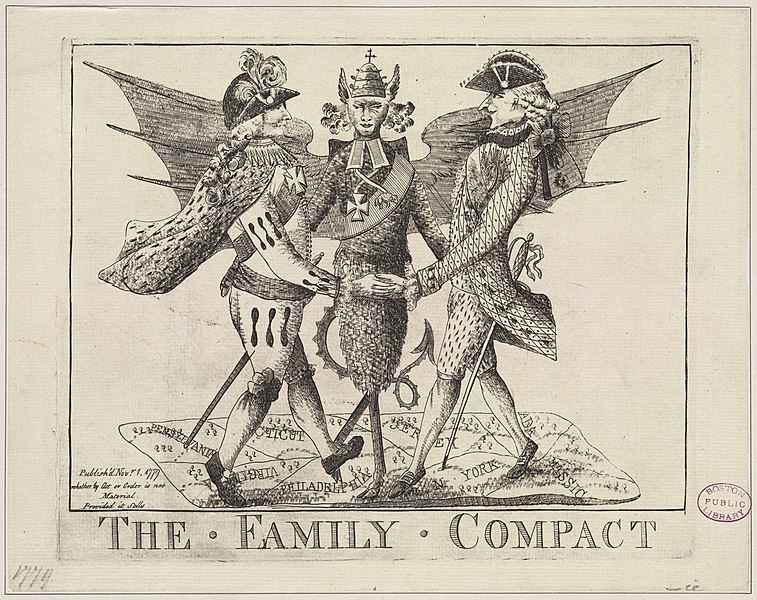

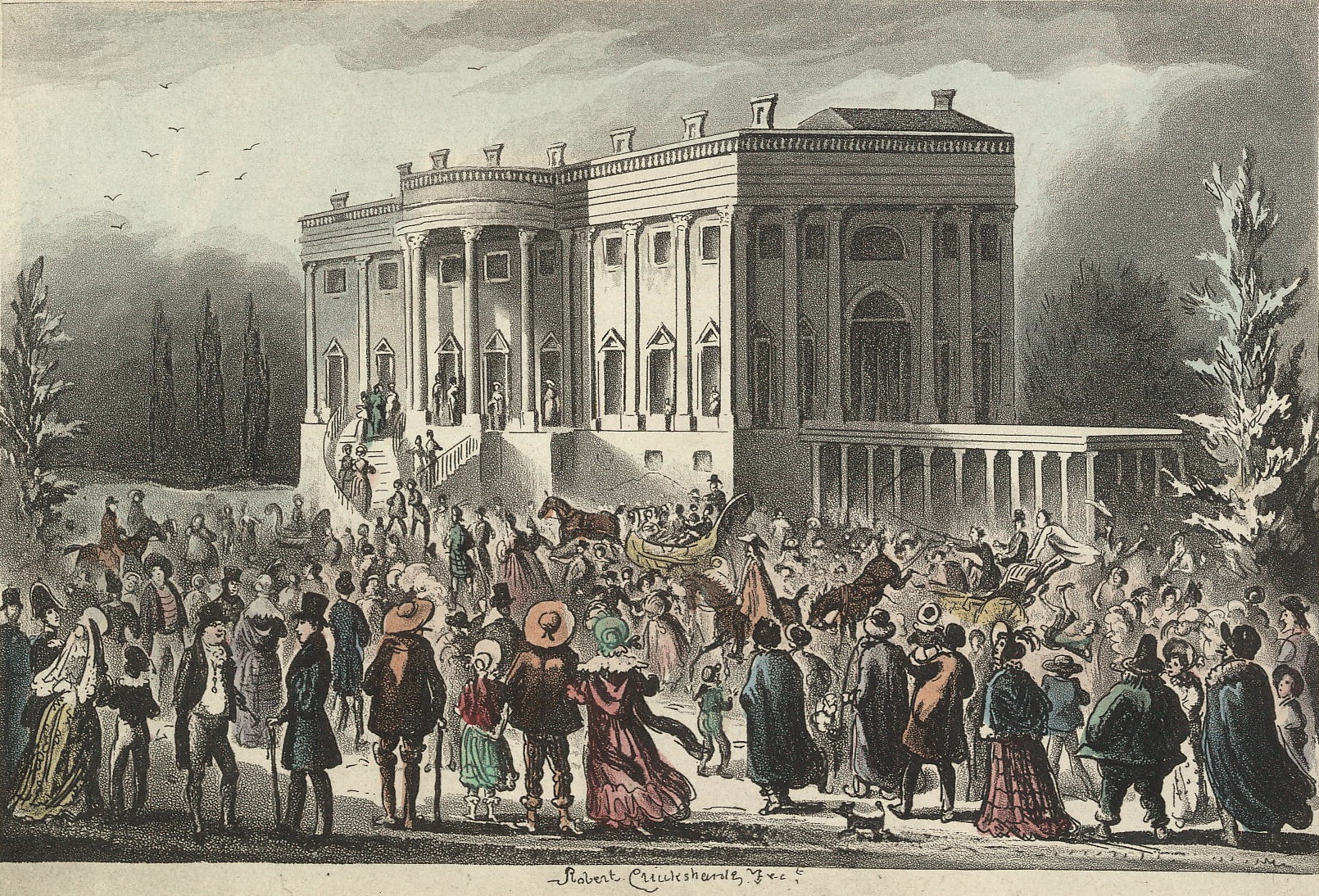

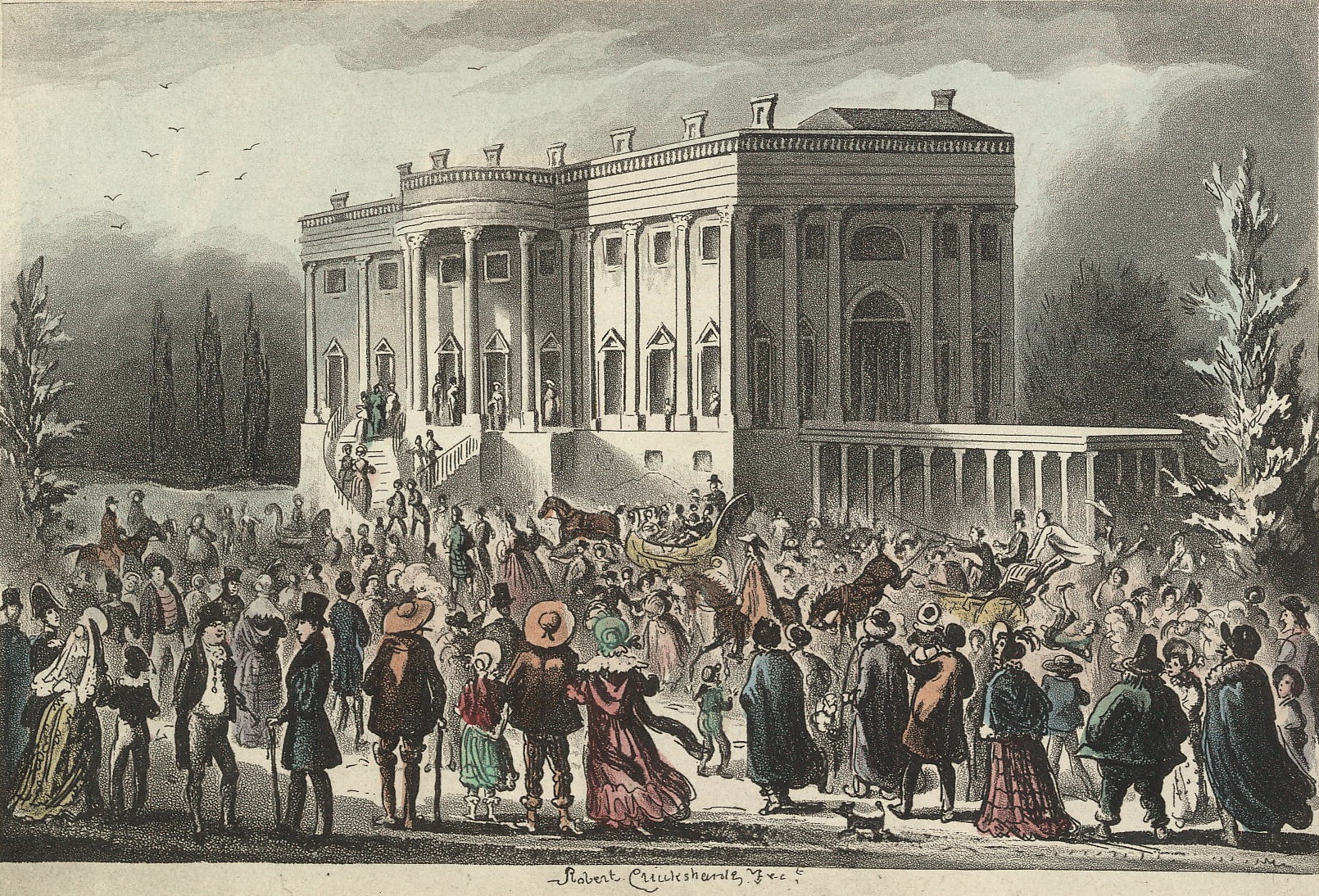

Despite the fact that Jackson had effectively announced the end of American democracy for the time being, the mood in Washington was not sombre while he did so. Jackson famously liked throwing parties for the "common people" of Washington - these "common people", naturally, were Republican Party lackeys and local slaveowners. The Party of National Reorganization, held after the speech and depicted here, was famously large; and while Jacksonian propaganda reported how enjoyable the party was, it famously ended on two accidental defenestrations and one trampling.

The end of the American civil war would prove to be a momentous moment in American history, as Jackson, thinking his position would only continue to stand under a different political system that the one currently in place during the Compromise Constitution (one that explicitly tried to disperse power amongst as many people as possible, and gave both states and the judiciary large possibilities of stopping any reform that the Executive would think of as necessary or desirable). Especially concerned after the defeat of the Whig rebels, he immediately decided that the current Constitution would not do, and, in a particularly momentous decision to the young United States, decided to do away with democratic state government altogether, justified in the fact that all States had had at least some members of government that supported either Clay, the Burrites or Calhoun in the War of the Supremes.

The new Government of National Reorganization, ran by Jackson with almost absolute power, to him was styled in a way reminiscent of Julius Caesar. To many, especially those who had appreciated the similarities between Burr and Sulla, the perception of Jackson as “America’s Caesar” became especially ominous as State liberties were increasingly rolled back, and the American Republic was set to follow Rome into becoming an Empire.

Caesarian imagery was not lost to the Jackson régime, who commonly harkened back to Roman myths to justify the government. Particularly, Caesar and Octavian were idolized. "Fair Columbia's founding" (left), a painting attributed to the Jacksonian epoch, particularly reflects this. Statutes of Caesar, Octavian and Jackson (right two, as an example) were erected throughout the country

While this was not precisely the case, this does not mean that the Period of National Reorganization was minor; in fact, it was one of America’s most tyrannical periods, one recalled to even to this day (by some) as a dark day for American democracy. For the first time in history, America toyed with a unitary government, changing its territorial ordinance; no longer would it be a nation of States, but one of Provinces; territories stripped even of their names and organized only numerically. Fundamental rights were greatly stripped back, even as Jackson provided basically every white man over 18 the status of American citizen. A particularly contentious amendment to the Constitution was the reinstatement of slavery at a national level - as Provinces no longer had the right to legislate independently of the National Government, laws imposed by Jackson’s decrees were applied the same way throughout the entire country. Soon, the Upper Mississippi was largely filled with slave owners which bought extremely cheap land expropriated from former native or rebel landowners, importing hundreds of slaves even in lands not traditionally suited to cotton farming. This brought great opposition from many Americans, especially in the north, where the abolitionist movement had greatly grown in the past years; however, considering the fact rebel militias had been absolutely crushed by Jacksonian forces, little could be done.

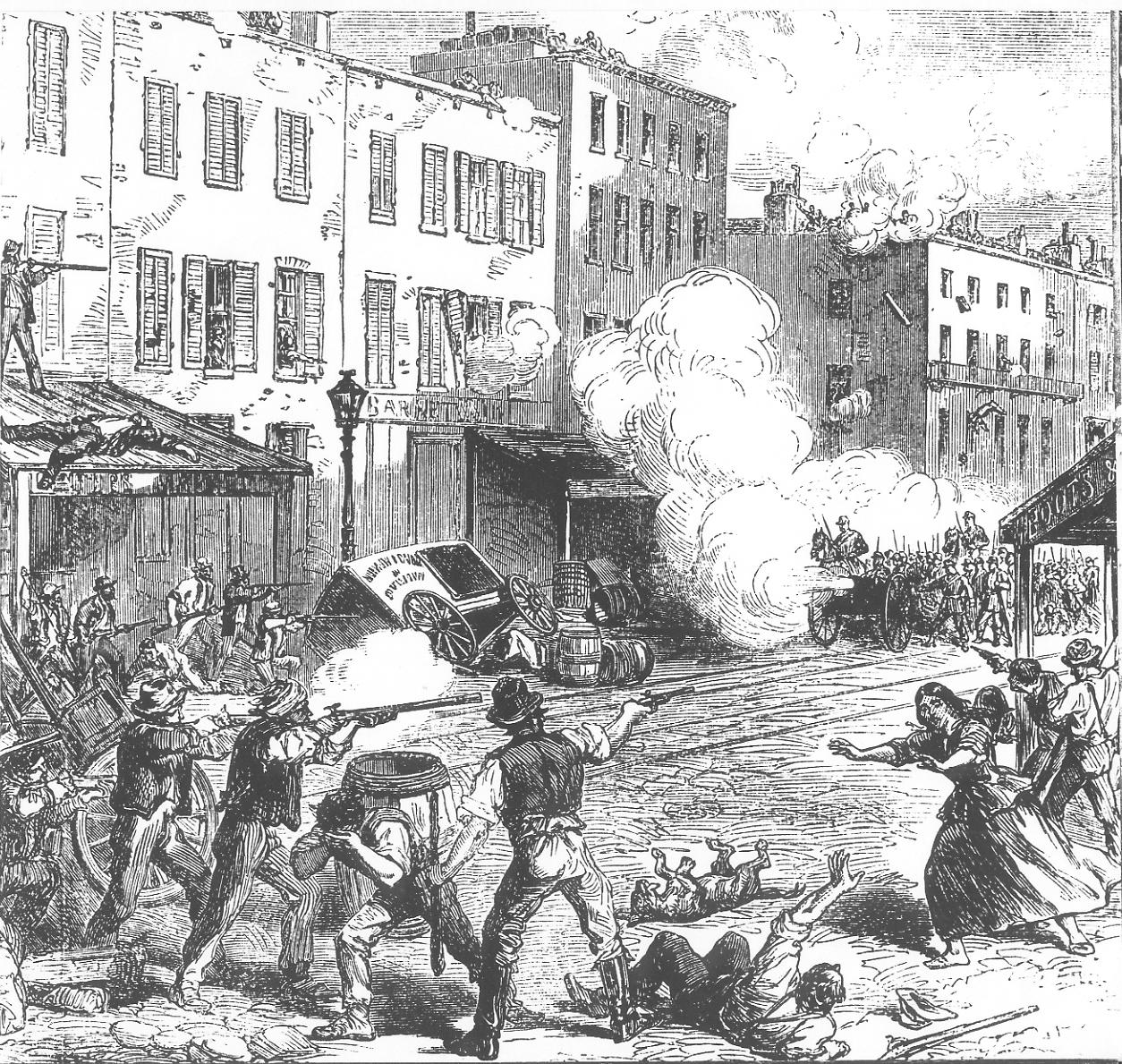

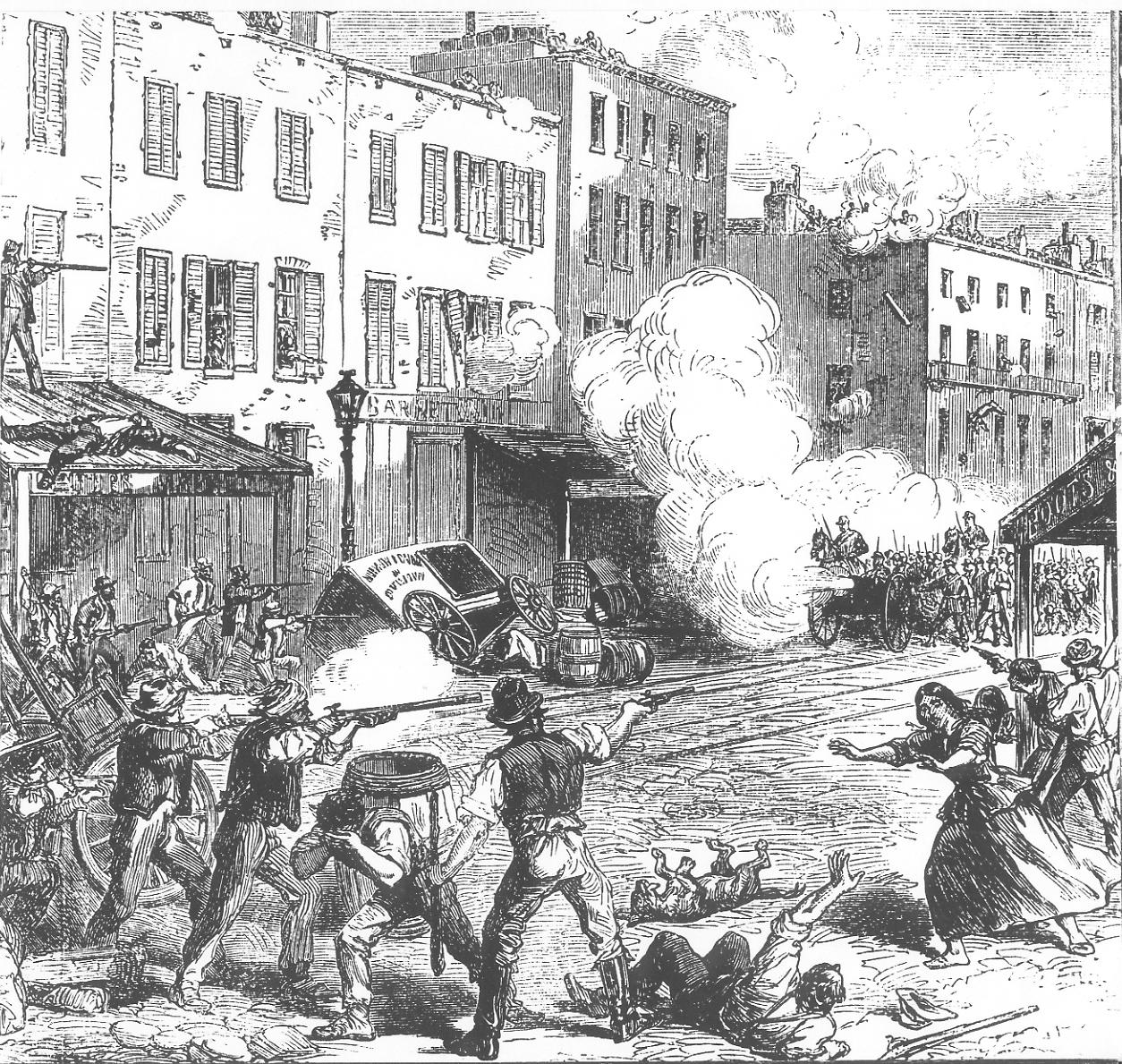

Bloody riots in Boston and New York over the arrival of hundreds of wealthy slave owners, who decided they wanted to live in formerly free states and supervise their plantations from afar, while bringing dozens of chattel slaves with them to the cities, soon began. Despite the fact Jacksonianism didn’t particularly care about popular opposition to slavery in the urban North, considering that the issue could be sidestepped now that most Provinces had areas at least somewhat dependent on newly homesteaded slave plantations, these riots soon began to be perceived as a new threat to public order, especially considering the fact that important opposition leaders like Henry Clay, John Pierre Burr and the Hamilton family had not been captured, but rather fled to Canada or the British Antilles. The increasingly paranoid Jacksonian administration soon began to crack down on protests, leading to the death of 30 Bostonians in the Bloody Sunday protests of 1837.

Bloody Sunday, 1837, or the Second Boston Massacre, was a fundamental event for Boston's history.

It is interesting to note that one of Andrew Jackson’s most influential policies in the long-term was the destruction of the National Bank, one of the few federal institutions that had survived the Compromises of America’s previous civil wars and that harked back to the Washington Administration, now considered a golden age in the history of the nation, without any civil wars or democratic decline which would so often plague the American system throughout the nineteenth century. Jackson had long had an opposition to the back, something which he had inherited from the Jeffersonian Republican Party. Jackson had had to deal with many different issues during his constitutional presidency and had not achieved the political capital necessary for the overhaul of something which, by 1830, was a veritable American tradition - however, with absolute power achieved after the War of the Supremes, one of his first actions was to destroy the bank, even ordering the demolition of the buildings it had occupied in Philadelphia. From now on and until nearly the start of the XX Century, the financial system in the United States was extremely deregulated, which led to an extremely large number of banks operating independently within the United States; over 1000 were registered by the Jacksonian government by 1845. The liberalization of a banking system, and the weakening of the gold standard as Colombian and British exports to the United States dried up, meant that the banking system would lead to periods of extreme runaway inflation in large cities, where the supply of money constantly ebbed and flowed without central controls.

Hunger and starvation, banished from the US urban areas after the Year Without A Sun, returned in 1837, not because of meteorological conditions but because of runaway inflation. Both poor and rich suffered: in New York City, records show that three months' rent in 1836 would afford five loafs of bread in 1837. A radical process of deflation as most II Province banks shut down in late 1837 would only make things worse.

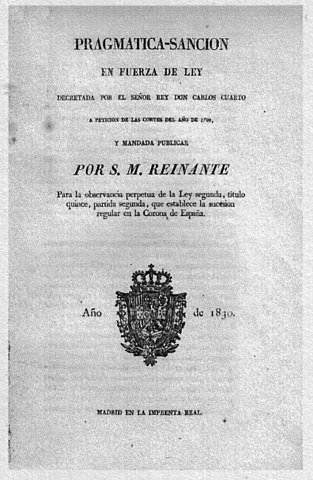

The Period of National Reorganization finally came to an end in 1839, with the expedition of the Third Constitution of the United States, signed by a sham Congress and Jackson in Dover, a city located in the fourth region of the United States and which would serve as the capital of the Union for the rest of the Jacksonian period (Philadelphia was too much of a hotbed of both anti-Jacksonian and abolitionist activity, while Washington had slowly been depopulated by constant changes in the civil service). The new Constitution, while formally still trapped in the clothing of democracy, left ample powers to the Executive (including removing any checks and balances on his actions, determining that re-election was direct, through all voters enfranchised, and not through the Electoral College, and allowing the President to dissolve Congress at any point), eliminated the federal system of the United States (notably, legalizing slavery throughout) and named Jackson as president-for-life (subject to the possibility of popular recall, in theory; anyone advocating for this would be imprisoned, in practice, under a resurrection of John Adams’ Sedition Act). With white militias deep under the control of Jackson, and all political opposition deeply quieted by either inclusion into Jackson’s inner circle (as can be seen through the Carolinians) or exile, imprisonment, or execution, it was clear that nothing would stop Jackson’s powers.”

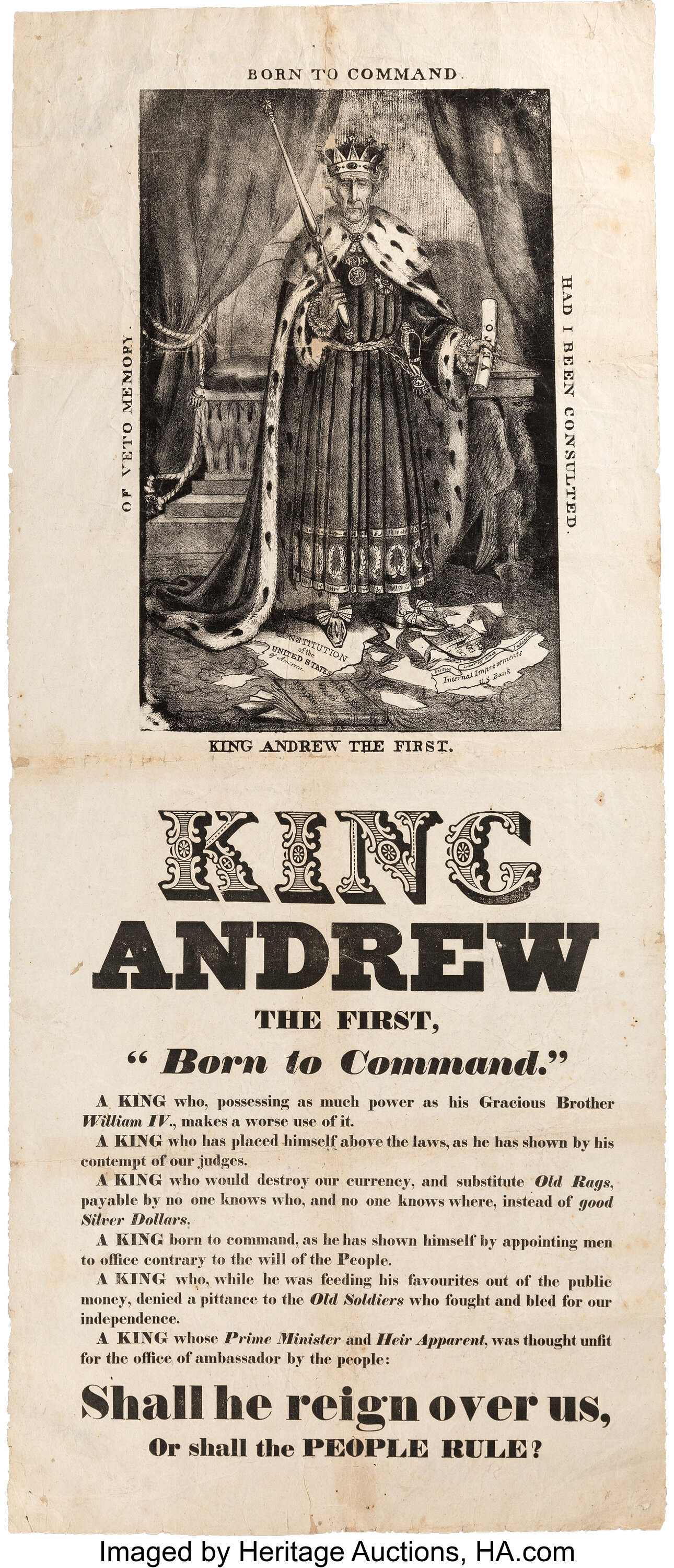

"King Andrew" propaganda was common throughout the Trenton System. The Dover System being born, eliminating the Federal structure of the United States and mostly removing the rule of law from America, seemed to validate opposition propaganda from before.

The consequences of this period of chaos and anarchy has brought great peril to our great State. All pecuniary advantages possibly achieved during this period have been lost to the States, which used their misgranted freedoms to rebel against our legitimate rule. The danger I have so warned before, of cultural conflict and strife between good folk and Indians and freed slaves has come to fruition, on a war that has laid waste to our land and our people. Rapidly, our population, wealth and power has dwindled to nothingness; it is a sad fact that today many hope to leave our land and go south, to lands that are under the domain of Papists and Indians. This is but logical, after so many years of misrule - what good man would prefer the current country of the Whig and the Indian, one covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages, only relieved by a half dozen cities, crowded and filled with foreign men with foreign tongues? When have we lost the goal of our noble Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by happy white families, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?

This is why the current status quo must come to an end. We must devise a new method of governance - one not encumbered by the Southron wish of rebellion or the Yankee wish of amassing wealth, one not encumbered by a misguided ploy of making equals out of unequals.

I announce that, as of today, the country must enter a Period of National Reorganization. The current Constitution is null and void; I shall rule with temporary decrees until order is reestablished under our proper, God-mandated system. The Congress, infiltrated with traitors and thieves, must be shuttered until new elections can be administered; the States must be purged of all traitorous elements.”

Despite the fact that Jackson had effectively announced the end of American democracy for the time being, the mood in Washington was not sombre while he did so. Jackson famously liked throwing parties for the "common people" of Washington - these "common people", naturally, were Republican Party lackeys and local slaveowners. The Party of National Reorganization, held after the speech and depicted here, was famously large; and while Jacksonian propaganda reported how enjoyable the party was, it famously ended on two accidental defenestrations and one trampling.

The end of the American civil war would prove to be a momentous moment in American history, as Jackson, thinking his position would only continue to stand under a different political system that the one currently in place during the Compromise Constitution (one that explicitly tried to disperse power amongst as many people as possible, and gave both states and the judiciary large possibilities of stopping any reform that the Executive would think of as necessary or desirable). Especially concerned after the defeat of the Whig rebels, he immediately decided that the current Constitution would not do, and, in a particularly momentous decision to the young United States, decided to do away with democratic state government altogether, justified in the fact that all States had had at least some members of government that supported either Clay, the Burrites or Calhoun in the War of the Supremes.

The new Government of National Reorganization, ran by Jackson with almost absolute power, to him was styled in a way reminiscent of Julius Caesar. To many, especially those who had appreciated the similarities between Burr and Sulla, the perception of Jackson as “America’s Caesar” became especially ominous as State liberties were increasingly rolled back, and the American Republic was set to follow Rome into becoming an Empire.

Caesarian imagery was not lost to the Jackson régime, who commonly harkened back to Roman myths to justify the government. Particularly, Caesar and Octavian were idolized. "Fair Columbia's founding" (left), a painting attributed to the Jacksonian epoch, particularly reflects this. Statutes of Caesar, Octavian and Jackson (right two, as an example) were erected throughout the country

While this was not precisely the case, this does not mean that the Period of National Reorganization was minor; in fact, it was one of America’s most tyrannical periods, one recalled to even to this day (by some) as a dark day for American democracy. For the first time in history, America toyed with a unitary government, changing its territorial ordinance; no longer would it be a nation of States, but one of Provinces; territories stripped even of their names and organized only numerically. Fundamental rights were greatly stripped back, even as Jackson provided basically every white man over 18 the status of American citizen. A particularly contentious amendment to the Constitution was the reinstatement of slavery at a national level - as Provinces no longer had the right to legislate independently of the National Government, laws imposed by Jackson’s decrees were applied the same way throughout the entire country. Soon, the Upper Mississippi was largely filled with slave owners which bought extremely cheap land expropriated from former native or rebel landowners, importing hundreds of slaves even in lands not traditionally suited to cotton farming. This brought great opposition from many Americans, especially in the north, where the abolitionist movement had greatly grown in the past years; however, considering the fact rebel militias had been absolutely crushed by Jacksonian forces, little could be done.

Bloody riots in Boston and New York over the arrival of hundreds of wealthy slave owners, who decided they wanted to live in formerly free states and supervise their plantations from afar, while bringing dozens of chattel slaves with them to the cities, soon began. Despite the fact Jacksonianism didn’t particularly care about popular opposition to slavery in the urban North, considering that the issue could be sidestepped now that most Provinces had areas at least somewhat dependent on newly homesteaded slave plantations, these riots soon began to be perceived as a new threat to public order, especially considering the fact that important opposition leaders like Henry Clay, John Pierre Burr and the Hamilton family had not been captured, but rather fled to Canada or the British Antilles. The increasingly paranoid Jacksonian administration soon began to crack down on protests, leading to the death of 30 Bostonians in the Bloody Sunday protests of 1837.

Bloody Sunday, 1837, or the Second Boston Massacre, was a fundamental event for Boston's history.

It is interesting to note that one of Andrew Jackson’s most influential policies in the long-term was the destruction of the National Bank, one of the few federal institutions that had survived the Compromises of America’s previous civil wars and that harked back to the Washington Administration, now considered a golden age in the history of the nation, without any civil wars or democratic decline which would so often plague the American system throughout the nineteenth century. Jackson had long had an opposition to the back, something which he had inherited from the Jeffersonian Republican Party. Jackson had had to deal with many different issues during his constitutional presidency and had not achieved the political capital necessary for the overhaul of something which, by 1830, was a veritable American tradition - however, with absolute power achieved after the War of the Supremes, one of his first actions was to destroy the bank, even ordering the demolition of the buildings it had occupied in Philadelphia. From now on and until nearly the start of the XX Century, the financial system in the United States was extremely deregulated, which led to an extremely large number of banks operating independently within the United States; over 1000 were registered by the Jacksonian government by 1845. The liberalization of a banking system, and the weakening of the gold standard as Colombian and British exports to the United States dried up, meant that the banking system would lead to periods of extreme runaway inflation in large cities, where the supply of money constantly ebbed and flowed without central controls.

Hunger and starvation, banished from the US urban areas after the Year Without A Sun, returned in 1837, not because of meteorological conditions but because of runaway inflation. Both poor and rich suffered: in New York City, records show that three months' rent in 1836 would afford five loafs of bread in 1837. A radical process of deflation as most II Province banks shut down in late 1837 would only make things worse.

The Period of National Reorganization finally came to an end in 1839, with the expedition of the Third Constitution of the United States, signed by a sham Congress and Jackson in Dover, a city located in the fourth region of the United States and which would serve as the capital of the Union for the rest of the Jacksonian period (Philadelphia was too much of a hotbed of both anti-Jacksonian and abolitionist activity, while Washington had slowly been depopulated by constant changes in the civil service). The new Constitution, while formally still trapped in the clothing of democracy, left ample powers to the Executive (including removing any checks and balances on his actions, determining that re-election was direct, through all voters enfranchised, and not through the Electoral College, and allowing the President to dissolve Congress at any point), eliminated the federal system of the United States (notably, legalizing slavery throughout) and named Jackson as president-for-life (subject to the possibility of popular recall, in theory; anyone advocating for this would be imprisoned, in practice, under a resurrection of John Adams’ Sedition Act). With white militias deep under the control of Jackson, and all political opposition deeply quieted by either inclusion into Jackson’s inner circle (as can be seen through the Carolinians) or exile, imprisonment, or execution, it was clear that nothing would stop Jackson’s powers.”

"King Andrew" propaganda was common throughout the Trenton System. The Dover System being born, eliminating the Federal structure of the United States and mostly removing the rule of law from America, seemed to validate opposition propaganda from before.