What an update. Hopefully Colombia gets Cuba, Santo Dominico, and Puerto Rico.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

If You Can Keep It: A Revolutionary Timeline

- Thread starter Fed

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 33 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXIV - "My Crown for the Paraná". The Election of 1838 Chapter XXV - En un coche de agua negra.... Chapter XXVI - ... Iré a Santiago. Chapter XXVI.5 - Blackness in Colombia Chapter XXVII - No Continent for Enslaved Men Chapter XXVIII - Francia, Domestic Edition Chapter XXIX - The Last Emperor Chapter XXX - The Mandate Shifts - Southern China in the Qing Collapse.Getting Philippines isn't a feasible option for Colombians but let alone an independent republic or maybe or possibly a British colony.What an update. Hopefully Colombia gets Cuba, Santo Dominico, and Puerto Rico.

Unless the Spanish want a British invasion, that's a very big no no. Especially since from 1815 Britain controlled Spain's military trade, and Spain's military training was based off on British tactics in the Napoleonic Wars, to which the British knew the counters off to a great deal.Maybe Spain would turn to the idea of conquering Portugal as a consolation prize for losing America?

Yeah, the Philippines are way too far away from any source of power in Colombia for Colombia to impose any sort of power.Getting Philippines isn't a feasible option for Colombians but let alone an independent republic or maybe or possibly a British colony.

Yeah, the Brits definitely wouldn't like that. Plus, it's not like Spain had strong territorial ambitions towards Portugal at this point in history - they didn't attempt a conquest iOTL with essentially the same loss of land.Unless the Spanish want a British invasion, that's a very big no no. Especially since from 1815 Britain controlled Spain's military trade, and Spain's military training was based off on British tactics in the Napoleonic Wars, to which the British knew the counters off to a great deal.

@Fed What's going to happen with the Ragamuffin war? Will Colombia act against Brazil to guarantee Rio Grande do Sul's independence? Will they try to annex it?

Ooooh. Nice catch! We’ll get there soon, but yup, Colombia will get involved in the Ragamuffin War.@Fed What's going to happen with the Ragamuffin war? Will Colombia act against Brazil to guarantee Rio Grande do Sul's independence? Will they try to annex it?

Chapter XXVI - ... Iré a Santiago.

¡Oh Cuba!

¡Oh ritmo de semillas secas!

Iré a Santiago.

¡Oh cintura caliente y gota de madera!

Iré a Santiago.

¡Arpa de troncos vivos, caimán, flor de tabaco!

Iré a Santiago. Siempre he dicho que yo iría a Santiago

en un coche de agua negra.

Iré a Santiago.

Brisa y alcohol en las ruedas, iré a Santiago.

Mi coral en la tiniebla, iré a Santiago.

El mar ahogado en la arena, iré a Santiago,

calor blanco, fruta muerta, iré a Santiago.

¡Oh bovino frescor de calaveras!

¡Oh Cuba!

¡Oh curva de suspiro y barro!

Iré a Santiago.

¡Oh ritmo de semillas secas!

Iré a Santiago.

¡Oh cintura caliente y gota de madera!

Iré a Santiago.

¡Arpa de troncos vivos, caimán, flor de tabaco!

Iré a Santiago. Siempre he dicho que yo iría a Santiago

en un coche de agua negra.

Iré a Santiago.

Brisa y alcohol en las ruedas, iré a Santiago.

Mi coral en la tiniebla, iré a Santiago.

El mar ahogado en la arena, iré a Santiago,

calor blanco, fruta muerta, iré a Santiago.

¡Oh bovino frescor de calaveras!

¡Oh Cuba!

¡Oh curva de suspiro y barro!

Iré a Santiago.

Abel Martí’s Speech to the Colombian Parliament, December 7, 1939

It’s a hundred years today since the most noble start of the liberation of Cuba. A hundred years since the first attempt by our American brothers and sisters to free our most noble isle from the yoke of slavery to a foreign power far away from our land, with no regards to Our America. The caged tiger of freedom had not yet roared in Cuba, just meekly whimpered as any resistance by our noble people was crushed by the heavy boot of the Spanish invader.

Yet in Cuba’s time of need, the Expedition was created. As you know, Colombia’s finest, led by Commander Sucre himself, sailed off from Cartagena in November 12; the day after a contingent left Nueva Orléans. Five frigates and ten brigantines reached the coasts of Mariel; and three frigates and five brigantines were sunk by Spanish forces.

Even with the navy mostly lost and no reinforcements in sight Sucre decided to brave the shores and land in Mariel. They faced General Barradas in Mariel and soundly defeated him. However, the walls of Havana were too great for even Sucre, and he died outside that great city, a martyr to the Cuban cause.

Cuba would not yet be free and part of this Perfect Union. But the noble Colombians who sacrificed their lives for its freedom will forever be remembered as eternal heroes for our noble Isle and our noble Union.”

The famous walls of Havana have mostly been torn down by a city anxious to grow. Havana, Colombia's second largest trade hub, boasts a population of over 5 million and has long since spread outside the city walls. However, historic portions remain; in this part, a plaque has been placed over a hole left behind by Colombian bombardment during the Mariel Expedition.

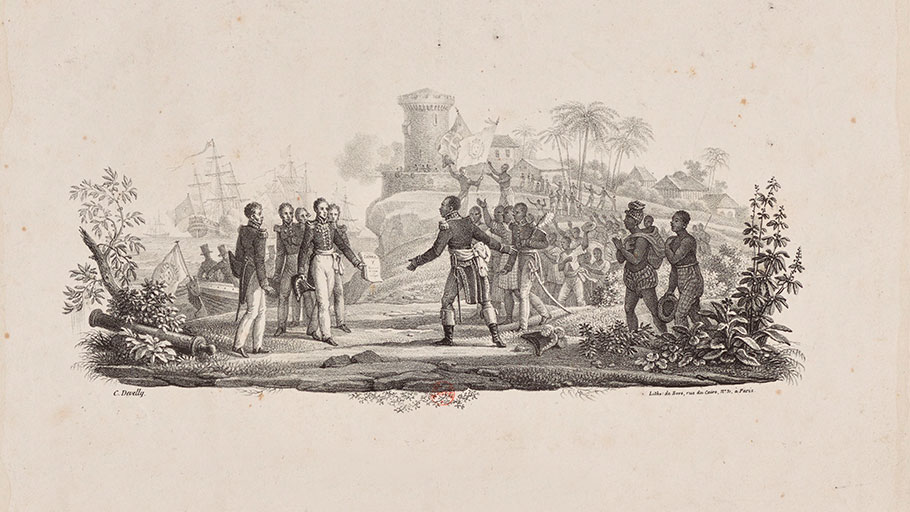

The 1841 painting that 'depicts' the death of Antonio José de Sucre, one of Colombia's greatest independence heroes, is today displayed at the Pantheon in Las Casas. However, the painting does not represent Sucre. The propaganda painting, which was actually started shortly before news of Sucre's death reached Las Casas, initially meant to honor Neogranadine hero Antonio Ricaurte, who was murdered at a Spanish arsenal in the 1810s. However, Congress repurposed the painting after news of the Mariel expedition reached coast.

In death, with Imperial ambitions profoundly dashed, Antonio José de Sucre truly joined the pantheon of great American liberators, together with Iturbide, Belgrano and Bolívar, and much more than other figures that would continue to participate in politics throughout the 1840s, like San Martín or Santander. The "Myth of Sucre", according to some, would give Colombia a taste for young populists.“While Sucre’s attempt to conquer Cuba ended in tragedy, there was another isle where the Colombians were far more successful; nearby Hispaniola, where the eastern half, dominated previously by white Spanish-speaking aristocrats, was being occupied by the Haitian state since 1822.

The remnants of the Colombian fleet withdrew from the failed Mariel expedition after Sucre’s death, and returned to Maracaibo expecting to disband, but instead they found express orders from Parliament to meet a group of Santo Domingo politicians and soldiers, led by José Núñez de Cáceres, to help with the anti-Haitian insurgency in Santo Domingo, led by Juan Pablo Duarte. The ships once again embarked in January 20 of 1840; a day before an express order from newly elect Emperor Francia decreed that Haiti was to be left to its devices. Too late, however, to stop the Dominican expedition.

Núñez and the Colombian troops laid siege to Santo Domingo and soon took over the town, faced only by token Haitian resistance as the majority of the army had left west to fight an uprising that threatened with taking Port-au-Prince. Indeed, within a few months all of Santo Domingo had been freed from Haitian intervention, and a treaty was signed with President Boyer of Haiti, which determined several provisions for Santo Domingo:

- The independence of the State of Santo Domingo, which was to be affiliated to the Colombian Empire,

- Colombia paying half of the indemnity Haiti owed to France, and giving land to the exiled whites who survived the Haitian Revolution in Santo Domingo,

- Colombia declaring itself in a state of “alliance and friendship with the Haitian State”, agreeing to help its government when help was required, and

- The institution of slavery being outlawed in Colombia (eventual abolition was already under place due to the Constitution’s ban on slavery, but the deal with Haiti eliminated the recognition of the institution under any sort, with any black citizen of Colombia that wished to leave the Empire being welcome in Haiti.

-Excerpt from El Nacimiento de una Nación by Juan Daniel Franco Mosquera, published by the Rosary University and the Xavierian University, Santafé de Bogotá, April 12, 1998. Translated to English in the University of Florida, Móbil, 2002.

Colombian troops meet with Haitians off Port-au-Prince, primed for negotiation. This painting, part of a series on the history of Colombia is clearly of pro-European nature and paints the Haitians as semi-civilized savages. This racist perception of the Colombian Empire towards Haitians would persist, which would lead to an overprotective attitude by the giant of the Americas to its smallest neighbor.

Law 13 of 1840

The Congress and the People of Colombia, in the name of His Majesty the Emperor,

Considering the triumphant triumph of the Emperor's forces in Puerto Príncipe, and the martyrdom of the Hero of Ayacucho, Antonio José de Sucre, against oppressive foes in the Island of Cuba, declares:

1. The Isle formerly named Hispaniola, will be now known as the Isla Libre,

2. General José Núñez de Cáceres will be named Governor-President of the State of Santo Domingo, until a State Constitution can be drafted and the Colombian Constitution is amended;

3. The Colombian Empire shall send a delegate to the government of Haiti, led by José María Córdova and the Dame of the Sun.

This, signed the 15th of March of 1840, in the name of His Honorable President of Government, José María Córdova, and the Emperor of the Republic, Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia.

"Alza la bandera, la bandera dominicana!

Alza la bandera, la bandera de la Wajira.

Alza la bandera, la bandera cubana!

Alza la bandera, la bandera puertorriqueña.

Esa bonita bandera contiene mi alma entera!

Y cuando yo me muera, entiérrame en mi tierra."

-Carnaval del Barrio, one of Luis Miguel Moro's showstoppers from the hit musical, Guajira Guantanamera.

The 'Eyesores of La Isla Libre', the first flag of the Dominican State, were flown between 1840 and 1847 (left) and 1848 and 1851 (center). Following the establishment of the Dominican Republic as a State of the Union in 1852, the flag would be modified to fit the current Dominican mold (right).

"The addition of Santo Domingo to the Union posed an interesting judicial question to the Colombian Empire, which had never changed its constitution before 1840 and now was faced with a situation on the ground that manifestly opposed the Constitution of 1820. Santo Domingo was very emphatically not a State invited to the original Anfictionic Council or to the Angostura and Cúcuta Congresses, which meant that there was no reference to the small island in Colombian law. It had been the wish of the Dominicans, however, not to be reabsorbed into the 'State of the Indies', as they believed the fall of Carlist Spain to the Colombians was inevitable, and did not want to be brought into union with the larger population of neighboring Cuba. Therefore, a complex quandary arose.

That being said, although the question was oft-discussed in the Faculties of Jurisprudence at the time, the situation had been resolved two years earlier with the integration of Paraguay into the Union. At that point, it had become clear Colombia was open to expansion, and the creation of new States (even though Paraguay, which had been invited to the Anfictionic Congress, was nominally still in the Colombian constitution from the outset). Therefore, it was not controversial when the Supreme Court authorised the modification of the Constitution by Parliament in its "Santo Domingo Ruling".

However, what did become extremely important for later legislation was the fact that the Supreme Court recognized both the legal nature of the inclusion of Santo Domingo and the process necessary for it to come into effect. Since Colombia considered itself the heir of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, and therefore laid claim to all the former Viceroyalties, the Court argued that this was not the admission of a new territory, but rather the secession of a piece of territory from the State of the Indies, much like the Indies had been created from territory nominally held by New Spain before.

Due to this particular legal nature, the Court was primed to recognize the necessity for the State government to authorize secession. The clear roadblock emerged, however; Cuba was not under Spanish control, and therefore, the State of the Antilles did not exist. Thus, it was necessary to ensure that the creation of a new State would be exclusively authorised by the Colombian Congress; of course, with extremely steep requirements, specifically approval by at least 70% of all three Chambers. Thus, Colombia asserted one more Federal right over the States; the capacity to divide them at will."

-Colombian territorial organization and autonomy, by Hernán Moreno Moro. Published in the National Autonomous University of Mexico, 1991.

An image of Boyer, Haiti's President, shortly after the Colombian War. While initially he was seen as a sellout, his cession of Haitian debt to Colombia would eventually make him into a revered figure.

“Boyer was greatly discredited by the peace treaty with the Colombian Empire, which essentially, in many citizens’ eyes, meant that Haiti became little more than a vassal of Colombia. This, combined with bad harvests, meant that by 1841 his position seemed untenable, and indeed, soon enough a serf rebellion led by former slave Faustin Soulouque began. Boyer himself realised that this was probably the end of him, and while frantically corresponding to both Francia in Las Casas and Núñez de Cáceres in Santo Domingo prepared to escape Port au Prince.

This wouldn’t prove to be necessary, as Francia, angry at the invasion of Santo Domingo going forward, readily agreed to uphold Haitian stability and its existing economic system. Remaining Colombian troops in Santo Domingo moved west, helping put down the serf rebellion with the aid of the Haitian military.

While an afterthought to Francia, seeking to uphold a treaty and punish the soldiers he saw as filibusters, his pressure to Cáceres so he would support Boyer in Haitian conflicts had tremendous implications in regards to Haitian history. First of all, it assured limited cooperation from Colombia - of course, nothing so strong under any non-Francista rulers (as those that didn’t support Francia’s ideas of ethnic integration would balk at treating a black state as an equal) but still, a far step up from the previous status of Haiti as a rogue state in international relations. Trade with Colombia would soon bring much wealth into the State.

Furthermore, Francia’s decision would also mean that security in Haiti would, to a degree, become a duty of Colombia’s Caribbean fleet. While the fleet wasn’t truly developed at the time (it wasn’t until the San Martín years that a united and strong fleet existed for Colombia), that meant that the Empire and its successors would have the responsibility of upholding Haitian stability, both due to a binding agreement and due to the fact that any Haitian upheaval would lead to over a million angry freedmen seeking to move east. Thirdly, Boyer remaining in power meant that the system of plantations so many Haitians had balked at would remain - while eventually it would be abolished, the plantation system meant Haiti remained a formidable producer of sugar and coffee - one that, until the twentieth century, competed with Colombia itself, and which permitted for a great degree of funds to go into industrialisation in the cities rapidly growing due to immigration of freed slaves from the rest of America. Last, but definitely not least, it assured France that Colombia would assume most of Haiti’s debt - and, concerned at the issues that might create in regards to trade with one of the largest markets in the nineteenth century, decided to slowly eliminate the Haitian debt altogether.

These moves assured that, while initially hated and controversial, today Boyer and Francia are praised with L’Ouverture as heroes of the Haitian fatherland.”

-Excerpt from “Francia and International Law”, by Juan Perón and Jean-Jacques Moïse.

Last edited:

Puerto Rico is next, right?

In the list of the Colombian elite, probably. But have in mind the island's fortifications were so daunting even the British failed to take San Juan in 1797. So maybe they'll have to look somewhere else....

That's also very true. The independentista movement of Latin American creoles did get to Puerto Rico (Antonio Valero de Bernabé was an important libertador who came from Puerto Rico) but it was far more muted than in the mainland or even Perú and Cuba. All very good reasons why Colombian expansion is going to find major roadblocks in the future!Puerto Rico was also really loyalist from what I read so winning the populace over might be a tad difficult.

Chapter XXVI.5 - Blackness in Colombia

(This one is just a small tidbit about Colombian race relations and the effects of the Haiti war. The article is based off this amazing BBC one iOTL.)

Last edited:

Deleted member 77383

So if America is similar to Colombia, what wars had occurred there? And what is civil unrest and domestic terrorism like there? And for the Cold War, what proxy wars occurred?

Thank you so much! These are very kind words.Incredible, incredible work.

We’re getting there eventually. That being said, as a preview: one of the big criticisms in internal policy towards Colombia is that it has “navel syndrome”; it almost never discusses international politics. The few times in history that Colombia has focused on diplomacy, it has punched far above its weight, but the country does not like doing so.So if America is similar to Colombia, what wars had occurred there? And what is civil unrest and domestic terrorism like there? And for the Cold War, what proxy wars occurred?

Chapter XXVII - No Continent for Enslaved Men

(The following chapter contains instances of overt white supremacism, slavery, the slave trade and mistreatment of slaves, which, just to make it clear to absolutely everyone, are absolutely vile things to do)

America

“It was thought, at the time of the drafting of the Philadelphia Constitution, that the biggest issue of the nascent United States would be slavery. To these effects, provisions relating to slavery, such as the Three-Fifths Compromise and the ban of the slave trade starting in 1808, were placed on the Constitution with the intent to ensure that all States would be reasonably happy with the status of slavery within each state, while agreeing to some basic elements in relation to international slavery and the establishment of a phasing-out system of slavery in the United States.

This was possible, most importantly, because of the generalized decline of the Southern economy, due to the fact that the South’s economy required very intensive labor due to the difficulty of the slave trade, and could not compete with the larger populations of the Nile River and the Indian subcontinent. Therefore, slavery in the early 1800s seemed far weaker than it would later in the United States; the Southern economy, further devastated by constant occupation, war and slave uprisings, led to the fact that the United States South’s cotton output decreased consistently every year, both in general terms as well as proportional to other cotton exporters, between 1790 and 1830. However, after the end of the War of the Supremes, this started to turn around sharply. The Carolinian Confederacy had started heavily subsidizing plantation farms, ensuring that those in the three Southern states would not suffer the devastation of the Whig West or Virginia. Once the country was mostly pacified and the Jackson Government was firmly in place, the Jacksonian government built on the previous subsidies of the Carolinian population, looking to grow the plantation system throughout the United States.

The cotton gin, however, did not act alone, and the development of slavery did not have an exclusively economic development. As economic development came to the forefront of the Jacksonian agenda at the end of the War of the Supremes, many feared the marginalization of slavers that had been present under the previous Federalist administrations would continue under Jackson. Thus, Finis Davis and other important Southern politicians (including the “disgraced” John C. Calhoun) would often look for private audiences with Jackson to lobby for the cause of slavery. However, it is still puzzling why these politicians were so concerned about the future of slavery. Had they only stared outside the windows of their carriages while strolling into the Hermitage, Jackson’s private plantation which doubled as the winter residency of the President of America during the Jacksonian epoch, would reveal that Jackson would not have the slightest interest in emancipating over two hundred of his own slaves. At the bottom of his heart, Jackson was a slaver through and through; and thus, he acted, in his own economic interests as well as what he saw were the best for the United States’ development as an agrarian (slaver) superpower.

These plantations were especially useful for the adaptation of the cotton gin into most American plantations. Although forms of the cotton gin had existed in India and the Far East since the V Century BCE, and the modern version had been invented in the 1790s by Eli Whitney, there was no widespread application of the cotton gin before the Jacksonian dictatorship in the United States, due to the general disrepair and instability of the American south, which prevented any sort of large-scale investment into the economic infrastructure of the country. However, the cotton gin was a gamechanger. Soon, productivity for each individual slave could shoot up, which entailed a great benefit to plantation farmers. With the system of plantation economy growing rapidly and heavily subsidized by the United States central government, it was no wonder that demand on slavery would increase.

The slave trade (although, inexplicably, not slavery itself) was by this point seen as a blight on nature by all European powers, including the United States. However, economic pressure would soon move the United States to change its perception of it, and the Jackson dictatorship ensured that all prohibition of the slave trade was repealed (without passing substitute laws that would legalize it, thus invoking the ire of the British and the French). The message, despite being more or less hidden under a veneer of plausible deniability, couldn’t be clearer. Scuttles of ships soon moved into the United States smuggling slaves, both from Latin America as well as from the rest of the world; most importantly, from Africa, where slave raiders began to act under a (somewhat) legal veneer for the first time in almost 20 years.

A membership card of the American Colonization Society.

The American Colonization Society’s founding of the town of Jackson, in the island of Sherbro, as an “observation outpost” supposed to oversee the nearby African coastline to found a city to take African freedmen. However, its true intention was much darker; instead it soon became a hub of the underground slave trade, kidnapping thousands of Africans from the nearby shorelines as well as from the island to bring them back to the United States. Particularly disturbing was the fact that many of those captured were former slaves taken by the British to the nearby city of Freetown in Sierra Leone. Soon, the floodgates of American importation meant the Atlantic trade would once again begin; heavily suppressed by British ships, of course, but nonetheless rather successful in bringing thousands of Africans to the United States where they would be subject to torturous slavery.

An unlikely ally of the United States in this period was the Brazilian Empire, which, unlike Colombia, which had already declared manumission of all slaves, retained the slave trade until far later in history. The Brazilians soon began openly trading with the United States in terms of slaves, exporting slaves in exchange for foreign investment, arms and other goods. In fact it is often said that the conflict between Colombia and the Brazilian Empire in 1846 was mostly a way to directly confront the relationship forming between the Brazilian Empire and the United States, although this seems as a particularly unlikely and Amerocentric view of Latin American relationships which doesn’t really hold up when considering that the Riograndese War was only intervened by the San Martín Government after the end of the Jacksonian regime. This probably is another in a long list of conspiracy theories that show Colombia as a foil to the United States and not as a country in its own right, popular in discussion groups amongst the “Papist Department Studies” in the United States and really nowhere else.

A map of Africa, 1836. Traditionally depleted areas of African territory which had been particularly raided by previous slave drives were hit particularly hard by the American and Brazilian unilateral (and mostly illegal) reopening of the slave trade. In particular, the settlement-rich area west of the Gulf of Guinea was affected by American private "filibusters", who ensured the impunity of the American government when other countries argued they were acting against international law; Brazil's naval Divisão Naval do Leste, in Cabinda, was particularly heinous, as, supposedly protecting the kingdoms of Kongo and Loango against the slave trade, they also subreptitiously brought many slaves back to the Brazilian Empire and America.

As important as the renovation of an international slave trade was, the most important element of the Jacksonian slave policy was internal. The elimination of independent State legislation after the end of the War of the Supremes had the unfortunate effect of legalizing slavery throughout the country, leading to the infamous effects of slaves moving into large Northern cities, which they thought would have both the benefits of living in a large mercantile city as well as providing a way out of the risk that being a slaver in the civil war South provided (few slavers survived the slave revolts that took over their plantations). However, the effect of the legalization of slavery was far more insidious, as it entailed that everyone born a slave would always be a slave, save express manumission, throughout the entire country. This meant the re-enslavement of thousands of freedmen who had rebelled against their slavers, fled to the North, who had been freed but were unable to prove this status in court, or simply free blacks who were born free. Black men and women throughout the North were bonded and taken to auction (children’s rights were, more or less, more tolerated in Jacksonian law enforcement; probably because children were easily to keep tabs on, which meant that once they were old enough they would be captured and auctioned off).

Furthermore, the Jackson government had authorized massive expropriations from rebels, which meant, especially to Native rebels in Muscogee (the State was notably a slave state, and therefore had a large Black population enslaved by the Civilized Tribes) and to Whigs in the West (especially in the State of Kentucky) meant that new slaves rushed into the internal market, ensuring that the high rise in demand would be met by a corresponding rise in supply (although the difficulties of kidnapping and forcing slaves into the markets entailed that prices still were very high). The arrival of new slaves from Brazil and Africa meant a rapid upswing in the slave populations. Thus, the black population of the United States rose from 18.1% in 1830 to 25.7% in 1850 (slaves, much like Natives, were not counted in the US Census, as they were not counted as people by a dreadfully supremacist Jackson government).

Native people being forced from their lands by American troops in a period of Native expropriation. Most Indians were not enslaved, but their slaves were taken and redistributed to white landowners.

It is interesting to note that Natives were enslaved throughout the Jackson government, but most of them were not exposed to the suffering of forced kidnapping and slavery, but instead carted off to the West in their own Trail of Tears. This is an interesting phenomenon, and one that has not been fully explained by historians. It is thought that a perception that Natives were too savage for hard work common amongst Americans at the time, and the low population base of Natives in comparison to plentiful Brazilian slavery, explains this. However, this does not recognize the fact that enslaving Natives would probably have been far cheaper than the risky international trade, which faced high costs per se as well as the high risks provided by the probability of a British, French, or Colombian intervention.

In any case, in the long term, the growth of slavery during the Jackson administration cannot be understated. Plantations grew throughout the United States throughout the period, settling the entire South, and the Mississippi Valley, where cheap homesteads ensured the rapid growth of plantation economies even in territories that were not apt for cotton growing, where large plantations of grain became the north. Even in the northern X Province, where the Red River acted as the Trenton Government’s claimed border with the United Kingdom (and which actually was at the time mostly under British control), several timber plantations were created. This would leave a double mark on American history; the stain of slavery would mean it was no longer considered a purely Southern sin (although this perception of slavery as a Southern artifact started to fade even earlier, as, even before the war of the Supremes, William Henry Harrison, Wabash’s second governor, implicitly legalized slavery in his state), but also, it brought Black people to occupy every major waterway and Province within the United States, thus making the African diaspora fundamental in making America the country it is today.

Slavery covered the North, as well as the South, during the Jacksonian dictatorship. In Wabash and Mississippi, among other States in the North and West, slaves were used for a variety of jobs, such as grain farming in large plantations across the Mississippi, lumbering and the clearing of land. To this day, the coastlines of the Mississippi remain majority black as far north as the Minnesota River. Slavery would no longer become a purely Southern phenomenon.

Now, the Jacksonian policy on slavery was not an unmitigated success, even for slavers (and was definitely a blatant failure in all regards for the moral soul of the United States); in fact, in the long term, the policy probably did the institution more harm than it benefitted it in the long term. Bringing slavery to the North did not make the North “complicit in slavery, and thus force them to abandon their outlandish ideas that slavery is an evil and not a positive good”, as Finis Davis, Jackson’s Vice-President, would write; instead, it emboldened abolitionists, who now saw slavery spread up into formerly Free territories. It also galvanized the North into confronting slavery, which had been ignored as a necessary evil to maintain the unity of the country by many Northerners when it was limited to the seven (eight) southernmost States. The abolitionist movement was greatly emboldened during the Jackson administration, where its most prominent leaders engaged in direct action against slavers; John Brown, today considered the father of abolitionism, started becoming important in raiding slave plantations throughout the Mississippi, bringing freed slaves to the underground resistance that still managed a low-grade insurgency against the Jackson government in the former State of Mississippi.”

-Slavery in the United States: A Brief History, an article to Times and Changes Magazine, Harvard Department of History.

---

Colombia

Because of the general manumission law passed by the Colombian Empire in its founding, the number of slaves in Colombia had gradually dwindled through time. It was true that slaves were still allowed in the country (and would continue to be, albeit indirectly, until the 1850s); however, by 1840 the youngest slaves were no longer newborn, but were perhaps 17 or 18, thanks to Colombia’s Free Wombs Law, which entailed that any person born in Colombian territory was free. Therefore, by the time of Francista war against Haiti, it was estimated that the population of enslaved Colombians had shrunk by as much as 30% from its height just before independence, until a spike of nearly 60% after the Peace of Port-au-Prince (widely thought to be caused by slaveowners reporting more slaves than they actually had in order to get higher compensation rate for their freed slaves).

I propose that the reduction of slavery was not as large as posited by traditional Colombian historiography. While the Law of Free Wombs did help many young Colombians achieve freedom, many were unfairly stripped of their right to freedom through modification of their birth certificates, through denial of their existance, or through other subterfuge means. Meanwhile, the reduction in slave population that did occur was caused through death due to wide-spread abuse of Black Africans (especially those in places like Peru and New Granada that were mostly employed in mining), as well as by a large Maroon population that would subsist throughout rural territories in Colombia.

However, the motives for Francia’s agreement with the Haitians seem much darker, considering its consequences. The liberation of the slaves was unambiguously a good thing which caused the end of an oppressive system in the Americas; however, it is also true that it was used by the Colombian Federal Government, as well as by State Governments, to gather data on Black Colombians for later deportation. An especially prescient case is that of the Deportation of the Palenque de San Basilio.

San Basilio had long been a thorn in the side of Creole authorities, both Spanish and independent. Located in the western part of the Canal del Dique, an alternate connection between the Magdalena River and the large port city of Cartagena, San Basilio had been an independent Black township since the rebellion led by Benkos Biohó in 1691. Creoles had called the palenque a barbarous town, or a rallying cry for slaves, ever since; and had long since tried to get rid of the small free territory that so irked white Cartagenians. However, the Maroon population of the city had stood strong against Spanish and independence-minded incursions and had mostly been forgotten and ignored, as an uncomfortable afterthought of a successful slave rebellion.

The Colombo-Haitian community remains large and connected to their territorial roots. Here, about 500 descendants from the San Basilio settlement meet in the Statue of Benkos Biohó, in Port-au-Prince, for the Day of Remembrance, which recalls their forced displacement from northern New Granada. To this day, these people have not received redress or compensation, although in the Falklands Case of 2019 the Supreme Court of Colombia opened the gate for reparations to exiled freedmen's descendants.

Santander, supreme leader of New Granada, resolved to fix this and saw Francia (who he deeply and strongly disliked, but often made common cause with as to avoid the repositioning of military-minded Bolivarians in the Colombian throne)’s deal with Boyer as a golden opportunity. He pressured the Neogranadine Parliament into passing a new law that would approve general amnesty for all “Maroons or runaway slaves”, and reintegration into ordinary Colombian life, with the granting of deeds of land on the table. This enticed the large population of Maroons that lived off the land but were interested in actually becoming their legal owners in the Colombian perception, and nearly the entire town’s male population registered on the system.

Santander had arranged for new plots of land to be given to them; plots of land that just happened to be located in the mostly barren Île de la Gonâve, in Haiti. Deportation swiftly proceeded. Similar events occurred throughout other known Maroon settlements throughout New Granada, such as around Quibdó and in Ipiales.

Fortunately, the white supremacist ambitions of the Colombian Empire were not realised, and a large black population remains in the country. Furthermore, those that were forced out, after initial decades of struggle and difficulty, managed to become citizens of a state that would become rather wealthy, even in comparison with its neighbor powers. However, it must not be ignored that this was an act of ethnic cleansing realised by the Neogranadine government. Similar acts occurred throughout the Colombian Empire, often cleansing entire regions of their black populations.

The Colombian Empire, after declaring peace with Haiti, arranged to abolish slavery “immediately”. In order to avoid strong conservative backlash from their decision, the country agreed to give an indemnization value of 300 Spanish dollars per slave to their owners (notably, while refusing to give any money to the freed slaves so that they started their own free lives, only paying for those who left for Haiti). Historical studies (Lamarck et. al.) have noticed that the grants of indemnity to slaveowners were considered one of the largest forms of upward concentration of wealth in history, as large amounts of State money was very rapidly given to what already was the wealthiest percentile of Colombia’s population.

In fact, it’s interesting to note that many current Colombian capitalist families – the Santamarías, the Quinteros, the Echeverris, the De Sotos, and many other names among them – initially transferred their funds from the previously lucrative slave mining and planting businesses to industry during the 1840s and 1850s. Historically, this has been attributed to the Colombian State (especially after the 1848 Revolution) became stronger and started supporting capitalism within the country. However, Lamarck (2011) argues that the main reason for this was a large influx of mobile capital achieved through the rapid liquidation of assets caused by manumission, which permitted the traditional owners of the means of production in a traditionally feudal society to transition to capitalism. (Footnote: it must be noted that Lamarck’s analysis is clearly very steeply based on the Marxist school of economics). Zhang (2009) and George (2017), in the style of the latter’s great-grandfather, argue that the main reason behind the growth of Colombian capitalism was the redistribution of land during the 1840s, which mostly benefitted people who were already landowners before, such as in the estancia system and the legalization of White coffeemakers in New Granada, while Native and Black traditional owners of land were deported or, especially after 1848, punished for their land-use.

-"Land, Wealth and Dominance - A Critical Approach at the Colombian Miracle, 1830-1850", by Juan José Mosquera, published at Quibdó University, 1971.

---

Brazil

Brazil is often ignored, even by race-critical theorists, when talking about the great upheaval of race relations in the American continent in the 1830s and 1840s. Focus comes exclusively into Colombian ethnic cleansing or American worsening of slavery. However, just as the Americans were starting to greatly worsen their race relations, a series of events came into being in Brazil that would provide a similar effect for the third big area in the American continent. This is because, while political issues shaped the changes in racial relations in Colombia and America, Brazil's approach was subtler, and based on the economics of the greatest slave-dependent economy of the world at the time. Although a great agricultural powerhouse, the country had fallen into hard times due to the instability of the regency era of the country, and its exportations of cotton and grain had fallen well below America's and, by 1832, even Colombia's. This greatly destabilized the Brazilian Empire, which, in and by itself, was also suffering from growing pains after Pedro I left the country and left his young son in charge. The Liberal regency had pretended to show that Republican government was viable in the country through a successful regency, but the opposite had happened. Massive revolts by Conservatives, who wished to be ruled by the Portuguese monarch, popped up in the northeast, while poor people in Grão-Pará and Maranhão rebelled against increasingly worse economic situations.

Contemporary paintings of the Sabinada (left) in Bahia, the Balaiada (centre) in Maranhão and the Cabanagem (right) in Grão-Pará. These massive rebellions were put down extremely brutally by Brazilian authorities and would forever become part of Northern Brazilian identity; for instance, "Balaiada: A Guerra do Maranhão" (title screen below) is currently the most watched animated series in Maranhão and much of Latin America, and has been praised for its excellent character-building and storyline.

Respite seemed to come to the Brazilians, as they rapidly became the last slave power in the continent, after the War of the Supremes. America had for over a decade been, at best, agnostic towards the continuation of slavery; both Burrites and Federalists disliked the practice and would prefer to see it phased out, and America's ambiguous support for the continuation of the slave trade which had been posited at the very start of the XIX century had all but disappeared during the Trenton System. Yet the Jacksonian government seemed to completely change this situation as, unofficially, but known to pretty much everyone, the slave trade once again began in the country. This emboldened Brazilians, who could now count on an ally to support their "endeavors" in the African continent. The Naval Division of the East, headquartered in Cabinda, in paper continued to "fight against the slave trade", as the British recognition of Brazilian independence rested upon this; in fact, instructions were given to keep a blind eye, and some particularly corrupt naval officers even participated in the slave trade by themselves.

With the reopening of a semi-legal slave trade from Africa, the Brazilian Empire suddenly had no need to take even the slightest of precautions when putting down slave revolts. Thus, the Sabinada, the Cabinada and the Cabinagem, large slave rebellions that had appeared in northern Brazil during the 1830s, were put down with undue ferocity, with the intent of "teaching the slaves a lesson". Thousands, up to 40% of the population of Maranhão, were murdered by Brazilian forces, as well as sickness and hunger resulting from the war. Even large amounts of revenge killings were meted out to the families of enslaved people, or those within the same plantation, as to leave a sense of fear and disconnect the rebel slave populations from any possible instigation.

While this revolt and improving economic conditions mostly put down all revolts in Maranhão, this violent attack on slaves of course had the opposite effect, as hatred towards what was seen as corrupt and violent Brazilian authorities continued to strengthen. The weak court had no choice but to continue attempting its plan of opposition to revolt, and throw more troops at the problem hoping that eventually slaves would not rebel anymore.

Of course, this left the Brazilian government blindsided when, in the south, the white, wealthy Riograndeses decided to rebel as well.

America

“It was thought, at the time of the drafting of the Philadelphia Constitution, that the biggest issue of the nascent United States would be slavery. To these effects, provisions relating to slavery, such as the Three-Fifths Compromise and the ban of the slave trade starting in 1808, were placed on the Constitution with the intent to ensure that all States would be reasonably happy with the status of slavery within each state, while agreeing to some basic elements in relation to international slavery and the establishment of a phasing-out system of slavery in the United States.

This was possible, most importantly, because of the generalized decline of the Southern economy, due to the fact that the South’s economy required very intensive labor due to the difficulty of the slave trade, and could not compete with the larger populations of the Nile River and the Indian subcontinent. Therefore, slavery in the early 1800s seemed far weaker than it would later in the United States; the Southern economy, further devastated by constant occupation, war and slave uprisings, led to the fact that the United States South’s cotton output decreased consistently every year, both in general terms as well as proportional to other cotton exporters, between 1790 and 1830. However, after the end of the War of the Supremes, this started to turn around sharply. The Carolinian Confederacy had started heavily subsidizing plantation farms, ensuring that those in the three Southern states would not suffer the devastation of the Whig West or Virginia. Once the country was mostly pacified and the Jackson Government was firmly in place, the Jacksonian government built on the previous subsidies of the Carolinian population, looking to grow the plantation system throughout the United States.

The cotton gin, however, did not act alone, and the development of slavery did not have an exclusively economic development. As economic development came to the forefront of the Jacksonian agenda at the end of the War of the Supremes, many feared the marginalization of slavers that had been present under the previous Federalist administrations would continue under Jackson. Thus, Finis Davis and other important Southern politicians (including the “disgraced” John C. Calhoun) would often look for private audiences with Jackson to lobby for the cause of slavery. However, it is still puzzling why these politicians were so concerned about the future of slavery. Had they only stared outside the windows of their carriages while strolling into the Hermitage, Jackson’s private plantation which doubled as the winter residency of the President of America during the Jacksonian epoch, would reveal that Jackson would not have the slightest interest in emancipating over two hundred of his own slaves. At the bottom of his heart, Jackson was a slaver through and through; and thus, he acted, in his own economic interests as well as what he saw were the best for the United States’ development as an agrarian (slaver) superpower.

These plantations were especially useful for the adaptation of the cotton gin into most American plantations. Although forms of the cotton gin had existed in India and the Far East since the V Century BCE, and the modern version had been invented in the 1790s by Eli Whitney, there was no widespread application of the cotton gin before the Jacksonian dictatorship in the United States, due to the general disrepair and instability of the American south, which prevented any sort of large-scale investment into the economic infrastructure of the country. However, the cotton gin was a gamechanger. Soon, productivity for each individual slave could shoot up, which entailed a great benefit to plantation farmers. With the system of plantation economy growing rapidly and heavily subsidized by the United States central government, it was no wonder that demand on slavery would increase.

The slave trade (although, inexplicably, not slavery itself) was by this point seen as a blight on nature by all European powers, including the United States. However, economic pressure would soon move the United States to change its perception of it, and the Jackson dictatorship ensured that all prohibition of the slave trade was repealed (without passing substitute laws that would legalize it, thus invoking the ire of the British and the French). The message, despite being more or less hidden under a veneer of plausible deniability, couldn’t be clearer. Scuttles of ships soon moved into the United States smuggling slaves, both from Latin America as well as from the rest of the world; most importantly, from Africa, where slave raiders began to act under a (somewhat) legal veneer for the first time in almost 20 years.

A membership card of the American Colonization Society.

The American Colonization Society’s founding of the town of Jackson, in the island of Sherbro, as an “observation outpost” supposed to oversee the nearby African coastline to found a city to take African freedmen. However, its true intention was much darker; instead it soon became a hub of the underground slave trade, kidnapping thousands of Africans from the nearby shorelines as well as from the island to bring them back to the United States. Particularly disturbing was the fact that many of those captured were former slaves taken by the British to the nearby city of Freetown in Sierra Leone. Soon, the floodgates of American importation meant the Atlantic trade would once again begin; heavily suppressed by British ships, of course, but nonetheless rather successful in bringing thousands of Africans to the United States where they would be subject to torturous slavery.

An unlikely ally of the United States in this period was the Brazilian Empire, which, unlike Colombia, which had already declared manumission of all slaves, retained the slave trade until far later in history. The Brazilians soon began openly trading with the United States in terms of slaves, exporting slaves in exchange for foreign investment, arms and other goods. In fact it is often said that the conflict between Colombia and the Brazilian Empire in 1846 was mostly a way to directly confront the relationship forming between the Brazilian Empire and the United States, although this seems as a particularly unlikely and Amerocentric view of Latin American relationships which doesn’t really hold up when considering that the Riograndese War was only intervened by the San Martín Government after the end of the Jacksonian regime. This probably is another in a long list of conspiracy theories that show Colombia as a foil to the United States and not as a country in its own right, popular in discussion groups amongst the “Papist Department Studies” in the United States and really nowhere else.

A map of Africa, 1836. Traditionally depleted areas of African territory which had been particularly raided by previous slave drives were hit particularly hard by the American and Brazilian unilateral (and mostly illegal) reopening of the slave trade. In particular, the settlement-rich area west of the Gulf of Guinea was affected by American private "filibusters", who ensured the impunity of the American government when other countries argued they were acting against international law; Brazil's naval Divisão Naval do Leste, in Cabinda, was particularly heinous, as, supposedly protecting the kingdoms of Kongo and Loango against the slave trade, they also subreptitiously brought many slaves back to the Brazilian Empire and America.

As important as the renovation of an international slave trade was, the most important element of the Jacksonian slave policy was internal. The elimination of independent State legislation after the end of the War of the Supremes had the unfortunate effect of legalizing slavery throughout the country, leading to the infamous effects of slaves moving into large Northern cities, which they thought would have both the benefits of living in a large mercantile city as well as providing a way out of the risk that being a slaver in the civil war South provided (few slavers survived the slave revolts that took over their plantations). However, the effect of the legalization of slavery was far more insidious, as it entailed that everyone born a slave would always be a slave, save express manumission, throughout the entire country. This meant the re-enslavement of thousands of freedmen who had rebelled against their slavers, fled to the North, who had been freed but were unable to prove this status in court, or simply free blacks who were born free. Black men and women throughout the North were bonded and taken to auction (children’s rights were, more or less, more tolerated in Jacksonian law enforcement; probably because children were easily to keep tabs on, which meant that once they were old enough they would be captured and auctioned off).

Furthermore, the Jackson government had authorized massive expropriations from rebels, which meant, especially to Native rebels in Muscogee (the State was notably a slave state, and therefore had a large Black population enslaved by the Civilized Tribes) and to Whigs in the West (especially in the State of Kentucky) meant that new slaves rushed into the internal market, ensuring that the high rise in demand would be met by a corresponding rise in supply (although the difficulties of kidnapping and forcing slaves into the markets entailed that prices still were very high). The arrival of new slaves from Brazil and Africa meant a rapid upswing in the slave populations. Thus, the black population of the United States rose from 18.1% in 1830 to 25.7% in 1850 (slaves, much like Natives, were not counted in the US Census, as they were not counted as people by a dreadfully supremacist Jackson government).

Native people being forced from their lands by American troops in a period of Native expropriation. Most Indians were not enslaved, but their slaves were taken and redistributed to white landowners.

It is interesting to note that Natives were enslaved throughout the Jackson government, but most of them were not exposed to the suffering of forced kidnapping and slavery, but instead carted off to the West in their own Trail of Tears. This is an interesting phenomenon, and one that has not been fully explained by historians. It is thought that a perception that Natives were too savage for hard work common amongst Americans at the time, and the low population base of Natives in comparison to plentiful Brazilian slavery, explains this. However, this does not recognize the fact that enslaving Natives would probably have been far cheaper than the risky international trade, which faced high costs per se as well as the high risks provided by the probability of a British, French, or Colombian intervention.

In any case, in the long term, the growth of slavery during the Jackson administration cannot be understated. Plantations grew throughout the United States throughout the period, settling the entire South, and the Mississippi Valley, where cheap homesteads ensured the rapid growth of plantation economies even in territories that were not apt for cotton growing, where large plantations of grain became the north. Even in the northern X Province, where the Red River acted as the Trenton Government’s claimed border with the United Kingdom (and which actually was at the time mostly under British control), several timber plantations were created. This would leave a double mark on American history; the stain of slavery would mean it was no longer considered a purely Southern sin (although this perception of slavery as a Southern artifact started to fade even earlier, as, even before the war of the Supremes, William Henry Harrison, Wabash’s second governor, implicitly legalized slavery in his state), but also, it brought Black people to occupy every major waterway and Province within the United States, thus making the African diaspora fundamental in making America the country it is today.

Slavery covered the North, as well as the South, during the Jacksonian dictatorship. In Wabash and Mississippi, among other States in the North and West, slaves were used for a variety of jobs, such as grain farming in large plantations across the Mississippi, lumbering and the clearing of land. To this day, the coastlines of the Mississippi remain majority black as far north as the Minnesota River. Slavery would no longer become a purely Southern phenomenon.

Now, the Jacksonian policy on slavery was not an unmitigated success, even for slavers (and was definitely a blatant failure in all regards for the moral soul of the United States); in fact, in the long term, the policy probably did the institution more harm than it benefitted it in the long term. Bringing slavery to the North did not make the North “complicit in slavery, and thus force them to abandon their outlandish ideas that slavery is an evil and not a positive good”, as Finis Davis, Jackson’s Vice-President, would write; instead, it emboldened abolitionists, who now saw slavery spread up into formerly Free territories. It also galvanized the North into confronting slavery, which had been ignored as a necessary evil to maintain the unity of the country by many Northerners when it was limited to the seven (eight) southernmost States. The abolitionist movement was greatly emboldened during the Jackson administration, where its most prominent leaders engaged in direct action against slavers; John Brown, today considered the father of abolitionism, started becoming important in raiding slave plantations throughout the Mississippi, bringing freed slaves to the underground resistance that still managed a low-grade insurgency against the Jackson government in the former State of Mississippi.”

-Slavery in the United States: A Brief History, an article to Times and Changes Magazine, Harvard Department of History.

---

Colombia

Because of the general manumission law passed by the Colombian Empire in its founding, the number of slaves in Colombia had gradually dwindled through time. It was true that slaves were still allowed in the country (and would continue to be, albeit indirectly, until the 1850s); however, by 1840 the youngest slaves were no longer newborn, but were perhaps 17 or 18, thanks to Colombia’s Free Wombs Law, which entailed that any person born in Colombian territory was free. Therefore, by the time of Francista war against Haiti, it was estimated that the population of enslaved Colombians had shrunk by as much as 30% from its height just before independence, until a spike of nearly 60% after the Peace of Port-au-Prince (widely thought to be caused by slaveowners reporting more slaves than they actually had in order to get higher compensation rate for their freed slaves).

I propose that the reduction of slavery was not as large as posited by traditional Colombian historiography. While the Law of Free Wombs did help many young Colombians achieve freedom, many were unfairly stripped of their right to freedom through modification of their birth certificates, through denial of their existance, or through other subterfuge means. Meanwhile, the reduction in slave population that did occur was caused through death due to wide-spread abuse of Black Africans (especially those in places like Peru and New Granada that were mostly employed in mining), as well as by a large Maroon population that would subsist throughout rural territories in Colombia.

However, the motives for Francia’s agreement with the Haitians seem much darker, considering its consequences. The liberation of the slaves was unambiguously a good thing which caused the end of an oppressive system in the Americas; however, it is also true that it was used by the Colombian Federal Government, as well as by State Governments, to gather data on Black Colombians for later deportation. An especially prescient case is that of the Deportation of the Palenque de San Basilio.

San Basilio had long been a thorn in the side of Creole authorities, both Spanish and independent. Located in the western part of the Canal del Dique, an alternate connection between the Magdalena River and the large port city of Cartagena, San Basilio had been an independent Black township since the rebellion led by Benkos Biohó in 1691. Creoles had called the palenque a barbarous town, or a rallying cry for slaves, ever since; and had long since tried to get rid of the small free territory that so irked white Cartagenians. However, the Maroon population of the city had stood strong against Spanish and independence-minded incursions and had mostly been forgotten and ignored, as an uncomfortable afterthought of a successful slave rebellion.

The Colombo-Haitian community remains large and connected to their territorial roots. Here, about 500 descendants from the San Basilio settlement meet in the Statue of Benkos Biohó, in Port-au-Prince, for the Day of Remembrance, which recalls their forced displacement from northern New Granada. To this day, these people have not received redress or compensation, although in the Falklands Case of 2019 the Supreme Court of Colombia opened the gate for reparations to exiled freedmen's descendants.

Santander, supreme leader of New Granada, resolved to fix this and saw Francia (who he deeply and strongly disliked, but often made common cause with as to avoid the repositioning of military-minded Bolivarians in the Colombian throne)’s deal with Boyer as a golden opportunity. He pressured the Neogranadine Parliament into passing a new law that would approve general amnesty for all “Maroons or runaway slaves”, and reintegration into ordinary Colombian life, with the granting of deeds of land on the table. This enticed the large population of Maroons that lived off the land but were interested in actually becoming their legal owners in the Colombian perception, and nearly the entire town’s male population registered on the system.

Santander had arranged for new plots of land to be given to them; plots of land that just happened to be located in the mostly barren Île de la Gonâve, in Haiti. Deportation swiftly proceeded. Similar events occurred throughout other known Maroon settlements throughout New Granada, such as around Quibdó and in Ipiales.

Fortunately, the white supremacist ambitions of the Colombian Empire were not realised, and a large black population remains in the country. Furthermore, those that were forced out, after initial decades of struggle and difficulty, managed to become citizens of a state that would become rather wealthy, even in comparison with its neighbor powers. However, it must not be ignored that this was an act of ethnic cleansing realised by the Neogranadine government. Similar acts occurred throughout the Colombian Empire, often cleansing entire regions of their black populations.

The Colombian Empire, after declaring peace with Haiti, arranged to abolish slavery “immediately”. In order to avoid strong conservative backlash from their decision, the country agreed to give an indemnization value of 300 Spanish dollars per slave to their owners (notably, while refusing to give any money to the freed slaves so that they started their own free lives, only paying for those who left for Haiti). Historical studies (Lamarck et. al.) have noticed that the grants of indemnity to slaveowners were considered one of the largest forms of upward concentration of wealth in history, as large amounts of State money was very rapidly given to what already was the wealthiest percentile of Colombia’s population.

In fact, it’s interesting to note that many current Colombian capitalist families – the Santamarías, the Quinteros, the Echeverris, the De Sotos, and many other names among them – initially transferred their funds from the previously lucrative slave mining and planting businesses to industry during the 1840s and 1850s. Historically, this has been attributed to the Colombian State (especially after the 1848 Revolution) became stronger and started supporting capitalism within the country. However, Lamarck (2011) argues that the main reason for this was a large influx of mobile capital achieved through the rapid liquidation of assets caused by manumission, which permitted the traditional owners of the means of production in a traditionally feudal society to transition to capitalism. (Footnote: it must be noted that Lamarck’s analysis is clearly very steeply based on the Marxist school of economics). Zhang (2009) and George (2017), in the style of the latter’s great-grandfather, argue that the main reason behind the growth of Colombian capitalism was the redistribution of land during the 1840s, which mostly benefitted people who were already landowners before, such as in the estancia system and the legalization of White coffeemakers in New Granada, while Native and Black traditional owners of land were deported or, especially after 1848, punished for their land-use.

-"Land, Wealth and Dominance - A Critical Approach at the Colombian Miracle, 1830-1850", by Juan José Mosquera, published at Quibdó University, 1971.

---

Brazil

Brazil is often ignored, even by race-critical theorists, when talking about the great upheaval of race relations in the American continent in the 1830s and 1840s. Focus comes exclusively into Colombian ethnic cleansing or American worsening of slavery. However, just as the Americans were starting to greatly worsen their race relations, a series of events came into being in Brazil that would provide a similar effect for the third big area in the American continent. This is because, while political issues shaped the changes in racial relations in Colombia and America, Brazil's approach was subtler, and based on the economics of the greatest slave-dependent economy of the world at the time. Although a great agricultural powerhouse, the country had fallen into hard times due to the instability of the regency era of the country, and its exportations of cotton and grain had fallen well below America's and, by 1832, even Colombia's. This greatly destabilized the Brazilian Empire, which, in and by itself, was also suffering from growing pains after Pedro I left the country and left his young son in charge. The Liberal regency had pretended to show that Republican government was viable in the country through a successful regency, but the opposite had happened. Massive revolts by Conservatives, who wished to be ruled by the Portuguese monarch, popped up in the northeast, while poor people in Grão-Pará and Maranhão rebelled against increasingly worse economic situations.

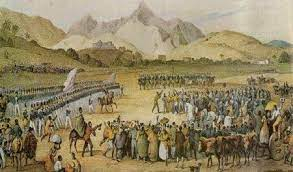

Contemporary paintings of the Sabinada (left) in Bahia, the Balaiada (centre) in Maranhão and the Cabanagem (right) in Grão-Pará. These massive rebellions were put down extremely brutally by Brazilian authorities and would forever become part of Northern Brazilian identity; for instance, "Balaiada: A Guerra do Maranhão" (title screen below) is currently the most watched animated series in Maranhão and much of Latin America, and has been praised for its excellent character-building and storyline.

Respite seemed to come to the Brazilians, as they rapidly became the last slave power in the continent, after the War of the Supremes. America had for over a decade been, at best, agnostic towards the continuation of slavery; both Burrites and Federalists disliked the practice and would prefer to see it phased out, and America's ambiguous support for the continuation of the slave trade which had been posited at the very start of the XIX century had all but disappeared during the Trenton System. Yet the Jacksonian government seemed to completely change this situation as, unofficially, but known to pretty much everyone, the slave trade once again began in the country. This emboldened Brazilians, who could now count on an ally to support their "endeavors" in the African continent. The Naval Division of the East, headquartered in Cabinda, in paper continued to "fight against the slave trade", as the British recognition of Brazilian independence rested upon this; in fact, instructions were given to keep a blind eye, and some particularly corrupt naval officers even participated in the slave trade by themselves.

With the reopening of a semi-legal slave trade from Africa, the Brazilian Empire suddenly had no need to take even the slightest of precautions when putting down slave revolts. Thus, the Sabinada, the Cabinada and the Cabinagem, large slave rebellions that had appeared in northern Brazil during the 1830s, were put down with undue ferocity, with the intent of "teaching the slaves a lesson". Thousands, up to 40% of the population of Maranhão, were murdered by Brazilian forces, as well as sickness and hunger resulting from the war. Even large amounts of revenge killings were meted out to the families of enslaved people, or those within the same plantation, as to leave a sense of fear and disconnect the rebel slave populations from any possible instigation.

While this revolt and improving economic conditions mostly put down all revolts in Maranhão, this violent attack on slaves of course had the opposite effect, as hatred towards what was seen as corrupt and violent Brazilian authorities continued to strengthen. The weak court had no choice but to continue attempting its plan of opposition to revolt, and throw more troops at the problem hoping that eventually slaves would not rebel anymore.

Of course, this left the Brazilian government blindsided when, in the south, the white, wealthy Riograndeses decided to rebel as well.

Last edited:

@Fed first time posting here, but I gotta say I'm intrigued by your latest update. Not that there's anything wrong with it; on the contrary, as gut-wrenching as it is for me seeing slavery becoming normalized in the U.S. (even if by Presidential-cum-dictatorial fiat), it nonetheless sets up an interesting allohistory for the future of the United States. Furthermore, I appreciate how you address and confront the canard of Latin American 'tolerance' in a pretty concise but detailed and refreshingly honest way.

The fact that it also takes place in a well-written timeline overall regarding a country that IMO had so much going against it in terms of remaining unified and stable (that it defies belief seeing it succeed without a very early POD*) only makes reading this all the more enjoyable. Keep up the good work!

*However, given you yourself intimate as much on the first page, this is by no means meant as a knock against this TL.

The fact that it also takes place in a well-written timeline overall regarding a country that IMO had so much going against it in terms of remaining unified and stable (that it defies belief seeing it succeed without a very early POD*) only makes reading this all the more enjoyable. Keep up the good work!

*However, given you yourself intimate as much on the first page, this is by no means meant as a knock against this TL.

Last edited:

El_Fodedor

Banned

Colombia has the potential to take Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná, considering the Gaúchos alone managed to take Santa Catarina and declare the Julian Republic, even if briefly.

Chapter XXVIII - Francia, Domestic Edition

“Francia’s rule, both to his supporters and his detractors, is undeniably radical. While opposed at every turn by the liberal, less militaristic factions of Parliament under the ever-powerful Santander, he did manage to pass many radical reforms through Senate decisions, as he packed the Senate with people who supported him and the Senate very often decided to mediate in Francia’s favour.

In regards to economic issues, Francia is most radically known for nationalising all unused land and giving it to military veterans from the Independence wars. Large estancias were created throughout the Empire, especially in Paraguay and La Plata, but also in large sectors of Venezuela and New Granada. These estancias were mostly given to local aristocracy, and employed by small farmers which produced extremely high quantities of horses, cattle and other livestock. The production of meat in the Colombian Empire skyrocketed. Small agricultural owners were benefited more in more mountainous areas that were too rugged to create large scale estancias. This was especially the case in the Andean region, where small farmers were given small tracts of land through a process of homesteading in many uncolonised regions.

However, it is this author’s opinion, as well as that of many other experts on the field (Rincón, 1998; O’Leary, 2003; Rausch, 2007; Alandete, 2009) that the greatest decision of economic impact in the Francia monarchy was one far less shiny than that of the homesteading in the west, but instead, the unification of the disparate postal organizations created by different State and provincial governments throughout the last decades of state building. The creation of the Colombian Post Office, as well as the granting of the title of Postmaster General (at the point, being considered a position of lesser import and, therefore, one that could be given out as a political prize without great problem) to the Mexican general Guadalupe Victoria would entail a massive change in inter-state politics.

Victoria, initially, looked to use the Post Office as a springboard for further political gain; it was well known, even at the time, that his ultimate goal was the Anfictionic Throne in Panama. The way forward, in his eyes, was simple; he was in control of a novel agency, whose results would be seen as essential to all politicians, and which would be the first true force outside of the army and the navy that could impose its presence throughout the different States of the Union. To ensure that the true weight of the Post Office was felt throughout the country, Santa Anna used an initially ample budget to manage several different aspects that were necessary for management; the first, a complex series of roads were co-financed, together with different State governments, unifying major hubs and ports (starting with an expansion of the roads between Mexico and Veracruz); and secondly, a truly veritable army of hired postmen, as well as a relatively large civil navy, which seeked to unify the different states relatively quickly. This was mostly managed through the hiring of llaneros, Neogranadine and Venezuelan horsemen which had felt a population explosion during the wars of independence and now, in many cases, were destitute and jobless; as well, to a lesser degree, through gauchos in the south and vaqueros in the north.

Ties between the regions, first through government correspondence, but then through eased migration and communication, a unified newspapers system and, eventually, the creation of pan-American infrastructure would be the true unifier of Colombia.

Due to Francia’s nationalistic positions on race, and his desires for mandatory race mixing that had previously been applied in Paraguay, this did not exclusively affect the white working class, which was something unique for the time. Many natives participated in Francia’s homesteading efforts, with native Americans being the chief winners of property in Perú and Charcas, as well as in several regions of the Neogranadine southeast and Mexico (mestizos predominated in land grants in western New Granada, while whites won most land in Venezuela and the Southern Cone). Miscegenation, while looked harshly upon by Parliament, was encouraged by the Executive, which, due to its control of the military, could enforce a permission for interracial marriage amongst the youngest in the military, who remained unmarried.

The difference between the Indian Republic and the Republic of Whites, the two predominant legal systems in the Colonial era and the early Empire, began to break down as natives began to access the economic aspects of the liberal state and began to be seen as property owners (and therefore, under the Napoleonic code, people); while natives, due to miscegenation laws, began to see an increasing amount of Creole grooms (and brides) which made overseers not the only white demographic to deal with them. The Constitutional division between the two systems was maintained, with no Constitutional amendments proposed by Francia passing the Liberal chokehold on the system, but in reality the Francista changes were profound.

Francista land reforms were fundamental in the recovery and wealth of Latin America. While previous leaders had managed to create credit for the Colombian state, only the land reforms allowed for Colombia’s vast patches of land, which had become unused, centralised and destroyed during the Wars of Independence, were finally put to use. Agricultural output skyrocketed, and soon, the Colombian people began seeing a greater food output and more income than ever before.

Small farmers that had gained homesteads in areas like the fertile Andes valleys soon began expanding the amount of crops grown in Colombia. Coffee and tea production took off, with small plots of land producing large amounts of both - while larger estates, especially those around the Gulf of Mexico, soon took off in the production of cotton, sugarcane and tobacco.

Francia tried to strike the confessional nature of the Colombian state, declaring that the Church would respond to the Colombian State, and created several secular education facilities under control of the military. This caused mild outrage by the Church, but Francia stopped short of closing down Church educational facilities, thus preventing a full-blown armed conflict with confessional sectors of the political establishment.