The McCarthy Cabinet & Staff

President Eugene McCarthy (MN, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Against all odds, Minnesota Senator Gene McCarthy has ascended to the Presidency. Campaigning on an end to the Vietnam War, moderate civil rights progress, and modest expansion of the Great Society, McCarthy narrowly defeated Richard Nixon. McCarthy is significantly to the left of how he campaigned, and it remains to be seen if he'll attempt to strike a balance, or return to his progressive leanings.

Vice President John Connally (TX, Conservative Democrat, Pro-Vietnam)

Before running for the Vice Presidency on the same ticket as Gene McCarthy, John Connally was the Governor of Texas, and, before that, John Kennedy’s Secretary of the Navy. Previously a protégé of Lyndon B. Johnson, Connally was instrumental in securing the nomination for McCarthy. Although considered a moderate in the South, Connally is a conservative in the grand scheme of things.

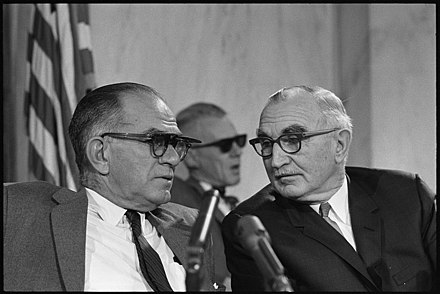

Secretary of State J. William Fulbright (AR, Conservative Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Under the Johnson Administration, the Senators who had opposed the Vietnam War were shuffled off to the near-powerless Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Fulbright had served as the Chairman of that committee, and was one of McCarthy’s few allies in the Senate. Although a segregationist, Fulbright is a major proponent of international cooperation and ending the Vietnam War.

Secretary of Treasury Russell Long (LA, Moderate Democrat, Pro-Vietnam)

The son of the famous politician Huey Long, Russell Long is an expert on taxes, and is one of McCarthy’s few personal friends. Long has served as both the Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, as well as the Senate Majority Whip. He was a key figure in passing much of the Great Society legislation. A Southern ‘Law and Order’ Democrat, Long tends to side against civil rights legislation, and has often expressed his opinion that the Supreme Court is too soft on crime.

Secretary of Defense David M. Shoup (IN, Moderate Independent, Anti-Vietnam)

A decorated, retired General of the United States Marine Corps, David M. Shoup was one of the most prominent military critics of the Vietnam War. Having previously served most notably as a Joint Chief of Staff in the Kennedy Administration, he has accepted the offer to serve as McCarthy’s Secretary of Defense. Shoup is also a proponent of using as small a military budget as possible without losing efficiency in the armed services.

Attorney General Wayne Morse (OR, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

One of the only two Senators to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Wayne Morse is a hero of the anti-war movement. An attorney by trade and previously a Republican, Morse was a minor candidate in the Democratic Primary of 1960, and was briefly supported by Gene McCarthy.

Postmaster General Joseph S. Clark Jr. (PA, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

The former Mayor of Philadelphia, Joseph Clark Jr. is one of the most progressive politicians in America. On election night, he lost his Senate seat to the Republican candidate Richard Schweiker, but was picked up by the new McCarthy administration to serve as Postmaster General. There is talk of removing the position of Postmaster General from the Cabinet, so Clark may not last long as a Cabinet member.

Secretary of the Interior Ernest Gruening (AK, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

The only other Senator to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Ernest Gruening is one of the most prominent voices in the anti-war movement. Gruening ran (and lost) as an Independent for Senator of Alaska on election night following his defeat in the Democratic primary for his Senate seat, as he was considered too opposed to the Vietnam War to be electable. Ironically, his anti-war credentials have earned him a Cabinet position instead. Gruening was integral to Alaskan statehood, and remains very popular there.

Secretary of Agriculture Fred R. Harris (OK, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

A liberal Senator from an increasingly conservative state, Harris is considered an up-and-comer in the Democratic Party. A firm supporter of the Great Society, Harris was appointed by Johnson to the National Advisory Commision on Civil Disorders, where he became increasingly concerned with the plight of inner city African Americans. One of Humphrey's campaign managers, Harris aligned with McCarthy after the Convention. He has Presidential aspirations of his own, and a Cabinet position may be a good first step.

Secretary of Commerce Albert Gore Sr. (TN, Moderate Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Although formerly in favour of military interventionism and the Vietnam War, Albert Gore slowly turned against the United States’ military escapades. A supporter of the Great Society, Gore is something of a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to legislation. A relative moderate on social issues, Gore did not sign the Southern Manifesto in favour of maintaining racial segregation, but has voted both for and against civil rights laws.

Secretary of Labor Ralph Yarborough (TX, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

One of Congress’ leading Progressive Democrats, Yarborough is a Southern populist who has consistently supported civil rights laws, environmental laws, the Great Society, the War on Poverty, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Known as “Smilin’ Ralph,” he had originally backed Robert Kennedy, but had been one of the delegates to shift to McCarthy. He previously had a bitter rivalry with John Connally, but they have recently reconciled.

Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Harold Hughes (IA, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

The Governor of Iowa, Hughes was the man who gave the nominating speech for Eugene McCarthy at the Democratic Convention. A former alcoholic, Hughes has been a champion against narcotic and alcohol addiction. Some consider him Presidential material, but Hughes seems more interested in his new capabilities as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Walter Mondale (MN, Moderate Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

McCarthy’s fellow Senator from Minnesota, Mondale remained quiet during the battle between Humphrey and McCarthy, not wanting to play favourites (though he privately preferred Humphrey, and worked for his campaign). Mondale considered declining a Cabinet position, but Humphrey talked him into it. Mondale is generally considered a moderate on economic and foreign policy issues yet a supporter of civil rights. Mondale had up until recently supported the Vietnam War, but reversed his position after McCarthy’s victory. His prominent support for fair housing and non-discriminatory spending has landed him the position of Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

Secretary of Transportation Claude Brinegar (CA, Conservative Independent, Pro-Vietnam)

An economic analyst and oil executive, Brinegar stands out compared to the rest of McCarthy’s cabinet. Environmentalists have complained especially on Brinegar’s appointment, claiming that the new McCarthy Administration is “too soft on big oil” with several prominent members of the Cabinet (including the Vice President, Secretary of Treasury, and the President himself) having ties to the oil industry.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Supreme Allied Commander Europe Matthew Ridgway (PA, Moderate Independent, Anti-Vietnam)

Ridgway previously served as a General in the Second World War and the Korean War, as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) under Truman and Eisenhower, and as Chief of Staff of the United States Army under Eisenhower. Along with Shoup and Gavin, Ridgway is one of the most prominent military opponents of the Vietnam War.

Chief of Staff of the United States Army Harold Keith Johnson (ND, Moderate Independent, Anti-Vietnam)

Harold Keith Johnson served as the US Army Chief of Staff for most of the Johnson Administration. Initially a supporter of a full reserve mobilization to fight in South Vietnam, Harold Johnson eventually became more skeptical of the likelihood of success in the Vietnam War, but never openly opposed it. He has been allowed to keep his position as Chief of Staff as a sign of military continuity, but only on the condition that he works to prepare the army for withdrawal from Vietnam.

Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation J. Edgar Hoover (DC, Conservative Republican, Pro-Vietnam)

J. Edgar Hoover is one of the most powerful men in Washington, having served as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation since the Coolidge Administration of the 1920s. Although a publicly popular figure, behind the scenes, Hoover is the ringleader of large scale domestic spying, illegal wiretapping, and all sorts of 'below-board' government activities. No President yet has attempted to remove Hoover for fear of "reprisal," and McCarthy isn't about to try, despite his dim view of America's security agencies.

Director of the Central Intelligence Agency James M. Gavin (NY, Progressive Independent, Anti-Vietnam)

A Lieutenant General during the Second World War, “Jumpin’ Jim” was famous for taking part in the combat jumps of the paratroopers under his command. He worked to desegregate the military, being called one of the most colour-blind generals of the war. Gavin was brought out of retirement by John Kennedy to serve as Ambassador to France, and had been approached by the Dump Johnson Movement to run as a candidate before they settled on McCarthy. Now, he serves as head of the CIA, in McCarthy's attempts to reign in the agency.

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations George Ball (NY, Moderate Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

The only prominent member of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations who was opposed to the Vietnam War, George Ball is also the only member of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to retain an important position in the McCarthy administration.

------------------------------------------------------------------

First Lady Abigail McCarthy

Although not entirely politically inclined, Abigail McCarthy played a large part in her husband’s campaign, especially when it came to women’s and Catholic groups, and distribution of campaign materials. A personal friend of Coretta Scott King, Abigail is a strong supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. Abigail goes into the White House with her husband and four teenage children: Mary, Margaret, Ellen, and Michael.

White House Chief of Staff Blair Clark (NY, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

McCarthy’s campaign manager, Clark had previously been a staunch supporter of the Kennedy family, but switched over to McCarthy when Bobby Kennedy refused to run in the New Hampshire Primary. Clark corralled McCarthy through the primaries and the campaign, and pulled strings at the convention to make sure the balloting went smoothly.

White House Senior Advisor Curtis Gans (NY, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Along with Lowenstein, Gans was one of the original founders of the Dump Johnson movement. Although less actively involved as Lowenstein and Miller, Gans still provided support to the McCarthy campaign throughout 1967 and 1968. Lowenstein has since had a falling out with McCarthy over the direction of the campaign and having John Connally in the Vice Presidential slot, and remains in the House of Representatives.

White House Deputy Advisor Midge Miller (WI, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Although she came a little later than Lowenstein and Gans, Midge Miller was one of the leaders of the Dump Johnson Movement. Although not as well known, she has been equally instrumental, serving as the nebulous McCarthy’s “handler” during and after the campaign.

White House Deputy Advisor Marty Peretz (NY, Moderate Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

A behind-the-scenes benefactor of the McCarthy campaign, Peretz is a Harvard lecturer who has begun to get involved in journalism. He has shown interest in purchasing

The New Republic political magazine.

White House Press Secretary Seymour Hersh (IL, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

A Chicago journalist, Hersh came on as McCarthy’s campaign press secretary. Hersh had covered the Vietnam War extensively before the election. Since his appointment to White House Press Secretary, he has transferred his journalistic research on Vietnam to American war correspondent and journalist I.F. Stone.

Chief Speechwriter Jeremy Larner (IN, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

An author, college professor, and journalist, Larner was McCarthy’s chief speechwriter throughout the campaign in both the Democratic Primaries, the Democratic Convention, and the general election. He also worked with Harold Hughes and Julian Bond to write the nominating and seconding speeches for McCarthy at the Democratic Convention.

Director of the National Economic Council J. Howard Marshall (PA, Moderate Independent, Pro-Vietnam)

An oilman by trade, J. Howard Marshall has a long history of working with McCarthy, acting as a financial backer when McCarthy was running for Representative and Senator, in exchange for McCarthy supporting an oil pipeline that would go through his riding in Minnesota.

National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski (NY, Moderate Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

A supporter of realism when it comes to foreign policy, Brzezinski has been accused by both the right and left wing as being soft on Communism and being an unabashed American imperialist respectively. Brzezinski is the counterpart of Republican foreign policy expert Henry Kissinger.

President of Young Democrats of America Sam Brown (IO, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

Sam Brown had served as the youth organizer for McCarthy’s primary campaign, and was the main organizing force of the New Hampshire primary. Brown has since been upgraded to a similar position as the President of the youth branch of the Democratic Party.

UAW President Walter Reuther (MI, Progressive Democrat, Anti-Vietnam)

The longtime President of the United Automobile Workers union, Reuther has long been involved in supporting New Deal and Great Society, and had also come out against the Vietnam War. Although Reuther didn't overtly support McCarthy during the primaries or convention, he was a firm supporter of McCarthy's in the general election, and was a source of legitimacy among union members, who remained skeptical of the man who defeated Hubert Humphrey. In the White House, Reuther is an advisor on labour issues for McCarthy, but remains UAW President.