The Last Months of 1919, Part One: Acting President Volsky and the policy of „Inner Stabilization“

When Vice-President Vladimir Volsky took over the highest office in the (territorially) largest state on the planet, the Union of Equals was still in a state of shock. Rumours about the breadth and depth of the reactionary conspiracy were going wild, as anti-socialist hangers-on amateurishly attempted a few more attacks here and there without much success, while the counter-reaction caused horrible events, too, like the Massacre of Drochia in the Bessarabian Federative Republic, where a mob attacked followers of a local religious sect, the

Inochentists (who were known to be fervent tsarists who believed that the Romanov dynasty was descended from the Archangel Michael, but who had nothing to do with the terrorist act or in fact any other militant activity lately), and killed dozens.

Volsky was not shocked. He was determined. The world would soon discover that Volsky had quite a different set of priorities than Avksentiev – one which was indeed much more inward-looking than that of his cosmopolitan predecessor. He seized the initiative and the opportunity of the crisis to obtain the assent of the Council of the Union for his first project: A new federal bureau of intelligence would be established and tasked with combatting terrorism, domestic and external non-military threats to national security.

His second project, with which he sought to finance the first, already failed to achieve a majority in the Council, though: Volsky wanted to introduce a steeply progressive union-wide income tax, and task a branch of the new federal intelligence with helping to lay the groundwork for effective tax gathering and combatting tax evasion. While most federative republics agreed with these aims in principle, and in fact were already bringing such projects under way, few of them were OK with these powers being accrued by the federal level. Even the Ukrainian delegation, where fellow SRs governed in a similar coalition to the one which had brought Avkseniev / Volsky to power, voted against such centralistic overreach.

As the political chaos in the aftermath of Avksentiev’s assassination subsided, with hundreds of suspects apprehended, and his tax project was shot down by the Council of the Union, Vladimir Volsky saw that he had no choice but to slash federal spending. With surging agricultural exports, federal customs revenues began to increase, too. But the weight of the war debts was so heavy, not just on the federal level but also threatening the access to international credit for the Union’s largest Russian Federative Republic, where ambitious projects not just for the restoration and extension of the railroad network, but also for huge programs on the oblast and municipal level for the construction of modern housing had already been approved by the Duma but could not begin due to a lack of capital and accessible credit. To Volsky, solving the problem of federal revenue and this credit crunch was of tantamount importance – in part because the network of regional SR strongmen who formed his primary powerbase desperately relied on these construction programmes in order to consolidate their power in these troubled times, but also because Volsky considered the economic welfare of the Russian people, errrr, sorry, of the peoples of the Union of Equals, as more important than games for geopolitical influence.

Volsky made a choice he found easy to take – but which would prove not to be easy at all to push through, even though this time, the Council of the Union could not interfere because the management of the Union’s military forces was the president’s constitutional prerogative. He had his Minister of Defense, Jan Sierada, draft a plan how to reduce the current number of UoE troops deployed to foreign countries to 75 % by the end of next year, and to 50 % by the end of 1921, and how to cut back military spending by a third over the next eighteen months. Sierada sighed and obliged – but he knew that the kind of ideas he would have to develop would severly curb the space of maneuver of the Foreign Ministry, too. Predictably, Kerensky was furious and went on to become Volsky’s most outspoken critic within the federal government. But Kerensky was not Volsky’s most dangerous enemy – that was Pavel Lazimir, the grey eminence of the Union’s military policy. He made sure that military commanders were not held back or reprimanded when they publicly lambasted the president for his plans.

And Volsky’s plans turned out to be drastic. It entailed troop withdrawals from the Balkans which would necessitate earlier referenda in the Dobrugea, Thrace, Banat and other places, troop reductions in Prussia, and the sale of surplus materiel.

But earlier referenda lacked the support of Kerensky’s foreign office, and the sale of surplus materiel depended to a great extent on the course of negotiations in the Naval Disarmament Commission established by the Paris Peace Conference. Kerensky supported a naval disarmament treaty in principle, too, but he did not lend much support to Volsky’s initiatives for unilateral UoE disarmament promises even when the British, the French, the Italians, the Americans and the Japanese were not adequately reciprocating.

And so, until the end of the year, Volsky was not able to score a breakthrough on either of these fronts, negotiations with various international partners still being undertaken without concrete agreements yet. When we look at other countries in the following sub-installments, we’ll see that Volsky was not the only president weakened by internal divisions in his administration. More importantly, though, Volsky’s display of military modesty was not primarily aimed at the real reduction of federal spending – it was intended to convey to the UoE’s international “partners” that the Union was doing its utmost to keep its federal budget under control and was, thus, a frugal and credit-worthy housekeeper.

And indeed, this strategy began to show some of the desired effects. From November 1919 onwards, international newspapers vehiculated rumours about what we would today call a “haircut” on war debt from which the UoE would primarily benefit – often alluded to as being diplomatically and politically tied to the conclusion of the afore-mentioned disarmament and additional trade treaties.

But these were not the only effects which Volsky’s display of military self-restraint had.

The End of 1919, part 2: Calm in Poland, Chaos in Prussia

Volsky’s new course had opposite effects on the young neighboring republics of Poland and Prussia. In Poland, where elections in September 1919 had brought a splintered Sejm with fourteen parties in it, among whom the National Democrats obtained the relatively greatest share of votes (23.5 %) and seats (102 out of 386 seats). [1] The ND continued to seek the support of a “grand national coalition” which spanned from the Right to those parties of the Centre-Left not affiliated with either Pilsudski’s adventurism or the UoE, or representing national minorities. This broad coalition managed to get Wincenty Witos elected as the Polish Republic’s first President [2]. The new President and the Sejm-backed coalition government were relieved to hear of the UoE’s plans to cut back its military spending, since it further reduced the danger Poland saw itself in and allowed the young Second Republic to not divert all its meagre means into building up a large costly army.

UoE troop reduction in Prussia meant that the position of the Red Prussian government was so weakened that it could no longer make any corroborated demands on their Polish neighbors to withdraw from the areas assigned to the them by the Powers. Luxemburg and Liebknecht, and also August Thalheimer, who had succeeded the assassinated Liebknecht as Chairman of the People’s Commission, had never been the staunchest opponents of an unconditional peace with Poland anyway. Several idealistic, and increasingly desperate, initiatives to come to a face-saving agreement had been stonewalled by Warsaw over the past few months. When Volsky’s withdrawal plans became official, Witos met with Thalheimer and Luxemburg in neutral Stockholm, and the two leaders of Red Prussia finally agreed to a peace treaty in which all Polish-occupied territories were officially ceded to the Polish Republic.

When news of the Stockholm Agreement were printed in Germany, riots broke out in Berlin and elsewhere. The Free People’s State of Prussia did not have enough reliable security forces at its disposal to restore order, and so the IRSD leadership decided that mobilization through the workers’ and peasants’ councils was necessary. An extraordinary congress came together on November 27th, 1919, but its outcome was not what Luxemburg’s conciliatory “Russian” faction had hoped for. In Prussia’s Supreme Soviet, a pre-negotiated coalition between “Prussians” and the newly formed “Militants” led by

Fritz Wolffheim managed to rally a majority behind a “directive” which rejected the Stockholm Agreement, deposed Luxemburg and Thalheimer, and called all “German workers and peasants in Prussia” to gather for the defense of the “freedom and territorial integrity of our Free People’s State”.

While the returning Luxemburg and Thalheimer were caught by surprise, their rivals had planned and plotted for this moment well in advance. Wolffheim, who was elected as the new Spokesman of the Supreme Soviet, organized the election of Konrad Haenisch, a nationalist SPD member of the defunct pre-war Prussian Chamber of Deputies, as Chairman of the People’s Commission. Quickly, it became evident that “Prussians” and “Militants” had extended their feelers to other potential fellow travellers way beyond the strictly socialist sphere. The new leadership acted quickly: Luxemburg, Thalheimer and the rest of the “Russians” in leading state institutions were apprehended by the police on charges of high treason. With another of Haenisch’s first edicts, all charges against German “war criminals” were declared unlawful, the right of any such suspects to candidate in elections and serve in political offices was restored and all co-operation with The Hague was suspended until a peace treaty restoring Prussian and German independence and territorial integrity and defining the limits of international penal law would be concluded between a “legitimate” Prussian government and the other Hague parties. As far as paramilitary activity was concerned, local authorities were ordered to stop the campaign against “militant anti-repartitionists” and instead work towards a “reconciliation” of all available forces in preparation of the conversion of all and any armed resistance against “excesses of the occupiers” by “flying columns” fashioned after the ones which were emerging in the Irish struggle for independence. A group of mixed aristocratic and bourgeois intellectual composition around

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and

Oswald Spengler declared their support for such a “Prussian socialist” agenda, too, and the National Social Democrats joined in as well - it soon became clear that the coup had turned into a rallying call for the dispersed opposition to the partition of Prussia and Germany by the victorious Powers.

The “Prussian conspiracy” caught not only Luxemburg’s faction off guard. The Council for the Mandate of Prussia had been busy discussing troop reduction schemes – and in the other parts of Prussia, which Wolffheim and the new group in power sought to reintegrate, too, British and French occupation forces as well as Hannoverian and Ruhr militia had not anticipated such a turn of events, either. Dozens of town halls, workers’ councils, police stations and arsenals were taken over in the first days, seizing the momentum of the coup.

But it was not enough. When the shock subsided, the commander of the British forces in Germany, Herbert Plumer, ordered an offensive to take back control over a couple of Hannoverian towns which had been lost to the “Prussian restorationists”. The Polish Army was sending over 20,000 reinforcements into Silesia and Pommerania, The security forces of the Prussian Mandate, mostly UoE, were drawn together from the territory in order to free their comrades captured in Berlin and wrestle control over the capital back from the putschists. And along the Ruhr, syndicalist “Red-and-Black Guards” got back on their feet again with French weapons and assistance, and once again proved their value and prevented the formation of a coherent "Western nucleus" of the restorationists in Westphalia. In the Mandate of Saxony, the mostly Czechoslovak security forces were set in motion, too. By Christmas, the situation of the putschists looked hopeless.

[1] IOTL, the Nadeks formed an alliance with “National Unity”, the Christian Workers’ Party and the Polish Progressive Party. This “Popular National Union” list obtained 29 % of the votes and 140 out of 392 seats. ITTL, the four parties combined fare better than IOTL, obtaining almost 35 % of the votes and 170 seats, but they have not formed the electoral alliance beforehand. IOTL, they were united against a strong Pilsudski (while the Centre and Left splintered without fear). ITTL, Pilsudski has been defeated, apprehended and is being put on trial by Ukrainian authorities and his splinter of the PPS is weaker than the pro-coalition schism, so the Polish Right does not feel the pressure it did IOTL and thus remains just as splintered as OTL’s Centre and Left.

[2] The position of the President is more powerful than IOTL where the ND opposed a strong presidency, fearing what Pilsudski could do with such a position.

The End of 1919, part 3: Southern and Western Germany; Czechoslovakia

Throughout December, the streets of Berlin were stained with blood in a veritable civil war between the rivalling Prussian factions. It was the arrival of security forces from the Mandate of Saxony (Czechoslovak contingents and militia of the Free People’s State of Saxony) which tipped the balance against the putschists even before New Year’s Eve [1]. Wolffheim, Haenisch and their entire junta had fled the capital in the last hour when their defeat was becoming undeniable, but they were apprehended in Oranienburg at the outskirts of Berlin by a UoE-staffed Prussian Mandate Security unit and taken into custody. The fate of the leading putschists would be decided in 1920, but in all likelihood, it would not be as grim as that of the predecessors they had couped away: Luxemburg, Thalheimer and dozens of other leading International Revolutionary Social Democrats of the “Russian” faction had been court-martialed by the putschists and summarily shot throughout December in a desperate effort to decapitate the internal resistance against the “restoration”.

In a ceremony of showcase symbolical value, Saxon militiamen and their comrades from the “Russian” faction of Berlin’s IRSD lowered the Prussian Black and White, adorned by the short-lived regime with a hammer and a shovel, and hoisted the simple red flag once again. But beyond such symbolism, it was becoming increasingly clear at least to the Mandate powers and their administrators who would convene in January in Berlin to discuss the future of Prussia, there could not really be a return to the situation of the summer of 1919. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were dead, and although Kerensky’s Foreign Ministry were determined to save soviet power in Prussia, if their Acting President would not be willing to commit enough troops to bring the entire Mandate territory from Jüterbog to Insterburg back in line, extinguish the last holdouts of Restorationism and prevent another destabilization in the future, the other Powers might insist on receiving more influence over the Mandate of Prussia, and possibly install a different constitution. The danger of German chauvinism was lurking on the Far Right and on the Far Left, as the new General Secretary of the EFP, Aristide Briand, remarked, and it was by no means eliminated. To provide for a safe rebuilding of the continent and secure lasting peace, the reasonable and moderate currents in Germany would have to be strengthened, and the EFP members would have to commit themselves to a quantitatively and qualitatively increased presence at least in Prussia over a prolonged period of time.

Elsewhere in Germany, i.e. in its West and South, such “moderate and reasonable” forces achieved greater progress towards stabilizing their governments and co-operating with the Mandate authorities. The chaos in Prussia only reaffirmed the resolution of Adenauer in the Rheinland, Scheidemann in Hesse, Wirth in Baden, and Erzberger in Württemberg to continue their course of co-operation among other and with the EFP powers and hasten the social reforms aimed at draining the swamp of dissatisfaction from which militancy arose. The clearest materially visible sign of this consolidation of a new Southern German bloc of smaller states was the adoption of the new Bavarian Gulden (instead of the practically worthless Reichsmark) by Württemberg, Baden, Hesse, Rhineland and Saxony, too.

Of these five, Baden and Württemberg had gone through the parliamentarisation of their constitutions and formed broad coalition governments as early as a year ago already, and these governments had begun implementing reforms of taxation and social security and at the same time invited foreign investment into the peacetime conversion of their industries with far-reaching guarantees and concessions which would limit their governments‘ powers over industrial matters in the future but which they deemed inevitable in order to instill confidence and emphasise that their part of Germany was stable and reliable indeed.

The Rhenish Republic followed this course, and the extent to which Adenauer succeeded in this endeavour was not only evident in the fact that the Restorationists did not manage to get a foot on the ground in Prussia’s former Rhine Province at all. A look into the new Rhenish Parliament in Cologne, elected in 1919, provided an unambiguous impression, too: it was utterly dominated by an overwhelming majority of Adenauer’s Zentrum members. This had been made possible by the electoral laws which followed the model only recently adopted in France. Because this electoral system is important in understanding the French elections of 1919, too, both IOTL and ITTL, I shall explain it in a few words: Each French département, or Rhenish Kreis, was awarded a number of seats proportionate to its population. Each voter could cast as many votes as there were seats to be filled; he or she could split them on individual candidates or heap them all onto the same list. If a list or candidates received an absolute majority of votes, they would be awarded their seats directly. If this was not the case, then the number of votes would be divided by the number of seats to be allotted, yielding the Quotient, and every list would one seat for every time that their Quotient fit into their number of votes. If there were seats left to be allotted, then they would all go to the list with the most votes.

An example:

- Bonn has 6 seats.

- 97,400 votes were cast.

- No single candidate obtained an absolute majority.

- The Zentrum list received an average of 39,135 votes per candidate.

- Two liberal lists received averages of 12,008 and 9,250 votes respectively.

- The SPD received 13,651 average votes, another socialist list received 4,961 average votes.

- Three conservative lists received 6,135, 4,681 and 4,432 average votes respectively.

- A single candidate on a separate list received 2,747 votes.

- The Quotient is (97,400 / 6 =) 16,333 votes. The Zentrum list receives 2 seats for fulfilling the Quotient twice. No other list reaches the Quotient.

- 4 seats are left to be allotted, and they all go the Zentrum for being the list with the most average votes relatively.

- Thus, all 6 seats go to the Zentrum.

As a result of the hegemonial position of the Zentrum, whose diverging wings Adenauer managed to keep together, in combination with the splintering of the socialist, liberal, and conservative camps into various party lists who most of the time were unable to agree on common lists, 192 out of the 240 seats in the Rhenish parliament went to the Zentrum, with the SPD and National Liberals receiving most of the rest.

With such an overwhelming majority, Adenauer pushed through popular (e.g. unemployment insurance), necessary (e.g. tax reform) as well as controversial (a return to mostly church-run schools with little government oversight and a reversion of all other Kulturkampf measures, too, as well as a lopsided free trade agreement with France which compelled the Rhenish Republic to adopt any regulation concerning foreign trade taken in Paris without having a say in it) measures. Even the latter began to show its effects, though: Citroen, France’s premier producer of automobiles decided, in spite of the Prussian troubles of the late autumn of 1919, to build their next factory in the vicinity of Cologne, for example. [2]

Winning the „race to Berlin“ was just another of the many formidable military achievements of the young Czechoslovak Republic. Quite generally, one major difference between OTL’s Czechoslovak nation-building and TTL’s in 1919 is the different role which its military plays. ITTL, the Czechoslovak Legion is spared its odyssey through Civil War Russia and its late return; instead, it arrives together with its UoE allies as liberators of their home country. The Czechoslovak Army, formed with much less French influence and to a very large degree from the former Czechoslovak Legion in Russia, and its leaders have already left their imprint on the young republic. They have quickly repelled a Polish attempt to establish themselves in Těšínské Slezsko, and the Czechoslovak contingents have fought bravely in the May War and ever since managed to keep Saxony calm and stable with only light numbers – and now they even put a quick end to the adventurism which haunted their Northern neighbors again. Whether this was sheer luck and favourable circumstances, or the merit of military leaders like

Jan Syrový or the commander of the Mandate Security Forces for Saxony,

Josef Šnejdárek is difficult to ascertain objectively. In Czechoslovak public opinion, though, there were no two minds about this: their military was an enormous source of pride for the young nation, and an important force unifying Czechs and Slovaks (and keeping the German and Hungarian minorities away from participating in the inner circle of the organization of the emerging republic).

Czechoslovak nation-building ITTL shares a number of characteristics with the course of OTL: the five largest Czechoslovak (i.e. non-minority) parties still form their great coalition, and there are countless initiatives aimed at fostering Czechoslovak national identity and culture, among them also the establishment of a „

Czechoslovak Hussite Church“. At a closer look, differences become evident, though. The increased role of the former Czechoslovak Legion means that Francophile intellectuals do not play quite the dominant role they did IOTL, and while Tomaš Masaryk has still been elected as the first President of the young republic with an overwhelming margin, other groups leaning more towards the UoE and its transformative model, and of course the war heroes themselves are considerably more influential. Speaking of war heroes – one of them who died IOTL in a plane crash and possibly took into his grave a lot of potential for Slovak integration in the new republic was

Milan Rastislav Štefánik . ITTL, he lives [3], and he is not only a member of the newly elected parliament, but also the young republic’s Minister of the Defense.

More differences appear in the coalition’s economic policies. Czechoslovakia has inherited the lion’s share of the Habsburg Empire’s industrial production capacities, and a good deal of its natural resources required to run them, too. Most of them are owned and managed by ethnic Germans, though – a situation which was considered politico-strategically unfortunate IOTL, too, but which could not be helped, Masaryk, Beneš & co. thought. Well, ITTL they think differently, what with no relatively strong Germany (nor Austria, but that is OTL, too) disencouraging all too blatant discrimination and with no intense general counter-reaction to Bolshevik transformations. Therefore, ITTL

Antonin Němec’s Social Democrats and

Edvard Beneš’s

Popular Socialists (the latter members of the Green Internationale, like their right-agrarian coalition partners of the

Republican Party of Farmers and Peasants) have taken measures which strike a middle course between classical capitalism and the socialism of their Hungarian neighbors: a consultative „Council for Economic Development“ is established which sets a framework for industrial development, and while market economic structures are left in place, the Czechoslovak state has declared itself the owner of 50.1 % of the shares (or other form of property) of all industrial enterprises employing more than 1,000 workers.

In the agricultural sector, too, large estates (mostly held by German/Austrian and Hungarian former nobility) will be repartitioned in a process overseen by local councils (after UoE models), in which compensations are also decided upon.

Both measures have earned them the ire of the former elites among their now numerous German minority as well as of the Austrian government, but solid popularity from Czech and Slovak peasants and workers. Under these circumstances,

Bohumir Šmeral’s attempts to form a Czechoslovak section of the IRSDLP have met with very little enthusiasm and drawn only few followers, a development which has stabilised the Coalition Social Democrats greatly.

[1] Getting to Berlin is easy; you can just send your troops there by train, there are no fixed front lines in this civil war. But both the British and the UoE have their hands full controlling vast territories in turmoil with reduced troops, and the Poles, as has been stated before, are merely interesting in pacifying and securing their annexed territories. Therefore, Czechoslovak-occupied Saxony is both a calm and nearby jump-off point for a quick ride to Berlin aimed both at bringing the dangerous Northern neighbor to rest again and at acquiring more political capital. (Also, I enjoyed the idea of a role reversal compared to OTL, where Berlin sent the Reichswehr twice to meddle in Saxony and Thuringia when those lands had governments with communist participation in 1923.)

[2] A similar discussion was conducted IOTL – in the end, it was Ford who built a factory in Cologne.

[3] I’ll go with the hypothesis that his plane was shot down by Czechoslovak anti-aircraft fire by accident, the Italian sign of the plane he flew on having been mistaken for a Hungarian one. ITTL, there is no Czechoslovak-Hungarian war in 1919, so that accident cannot happen.

The End of 1919, part 4: Elections in France and Italy

The elections in France and Italy of November 1919 took place under two very different electoral systems, and in two very different political atmospheres. From a socialist viewpoint, both brought similarly dramatic disasters, though: new and old parties and blocs of the centre and centre-right were strengthened, garnished with a few socialist fig leaves, while principled socialists suffered from divisions and a political atmosphere which was increasingly difficult for them, scoring way worse than they had hoped, and even worse than they had expected.

In France, the last elections of 1914 had brought a parliament dominated by the centre-left

PRRRS – and then the Great War came, and with it the Union sacrée, the very broad coalition of conservative, liberal and socialist, monarchist and republican, moderate and radical, Catholic and anticlerical etc. political forces in France. The Great War brought horrible suffering to France, and the Union sacrée showed cracks, of course. Much of these cracks appeared on the grassroots of French politics, and they were transmitted very differentially onto the higher and highest echelons of France’s hetergenously structured political parties. The SFIO left the Union Sacrée under bottom-up pressure, for example, while the

Republican Socialists of

René Viviani,

Paul Painlevé and

Aristide Briand continued to stick to it and led many of the short-lived French wartime governments. Within the PRRRS, party leader

Joseph Caillaux voiced the popular despair over the sufferings brought about by the war and the desire to find a settlement with Germany, while others supported the quasi-dictatorial government of

Independent Radical Georges Clemenceau, who led France victoriously out of the Great War (hence his epithet “Père la Victoire”).

In 1919, as the war was more or less won, and the very last steps, in the form of the May War, had felt easy to take in a generally elated atmosphere of triumph and reborn hope, the pendulum of popular opinion swung back, and it hit France’s nascent mass parties on the Left and Centre-Left fairly hard. Doubts about the war were considered spineless and unpatriotic defeatism now, and those who had argued for an uncompromising course seemed revendicated now by the dissolution of the German arch-enemy into small and unthreatening statelets and France’s leading role in the post-war order and the EFP. Caillaux had become discredited by his reconciliatory stance towards Germany, and

Edouard Herriot led the PRRRS into the elections instead.

The SFIO was led by

Ludovic-Oscar Frossard

, a pacifist who had moved throughout the war from the Marxist Centre towards the Ultra-Left. He had surfed into office on the desperation of the French labour movement pressed hard by the war, but his opposition to the May War was no longer quite as popular, not even among truly radical socialists (not those who carried that historical label on their party’s badge…), many of whom saw the course of the May War as a triumph of socialism even in Germany over reactionary monarchism and the Prussian mésalliance of the landed aristocracy and industrial steel barons. And then, even the left wing of the SFIO among itself was shaken by the dispute over whether to join the IRSDLP unification or not.

Boris Souvarine, Raymond Péricat and

Charles Rappoport supported the unification, while Frossard and other fellow pacifists like

Louise Saumoneau,

François and

Marie Mayoux and

Albert Bourderon supported Frossard’s skepticism of Trotsky’s “Bonapartist adventurism in ultra-imperialist guise”.

Souvarine led a number of rebels out of the SFIO to found the French branch of the IRSDLP (in French PSIRT, for Parti Socialiste Internationale Révolutionaire du Travail). After the failed Italian Revolution, but also after the lists of candidates for the elections had been handed in, pressure from the remaining SFIO base – now less dominated by the radical left – forced Frossard to resign, and a group of Centrists installed the Parisian

André Léon Blum as the new General Secretary of the SFIO.

Socialists all over France were left confused and dispirited by all these schism and disputes, and while the PSIRT only managed to bring together a handful of lists of candidates for the election in large cities, the SFIO was still weakened by PSRIT-leaning radicals not all voting for SFIO lists, and even some of the most moderate SFIO supporters not voting for their own party’s lists where they deemed these too pacifistic (“Germanophile” was the preferred slander), often preferring the common lists of PRRRS and Republican Socialists (“la Gauche radicale”, as opposed to “la Gauche socialiste”).

The parties of the Centre and Centre-Right were extremely heterogeneous, too, and personal rivalries like that between Clemenceau and Poincaré haunted them, too. In contrast to the Centre-Left and Left, though, they felt that the patriotic fervor gripping the French nation in 1919 was wind in their sails, not blowing into their faces. Continuing the wartime tradition of broad alliance-building and attempting to make the most out of the military victory, the patriotic wave, Clemenceau’s popularity [1], and the electoral system which favours larger lists disproportionately over smaller ones, the “Bloc National” was created, spanning from the Republican Federation and the Independents and Conservatives over the Democratic Alliance to the Independent Radicals, to the exclusion only of extreme rightist groups like the

Action française.

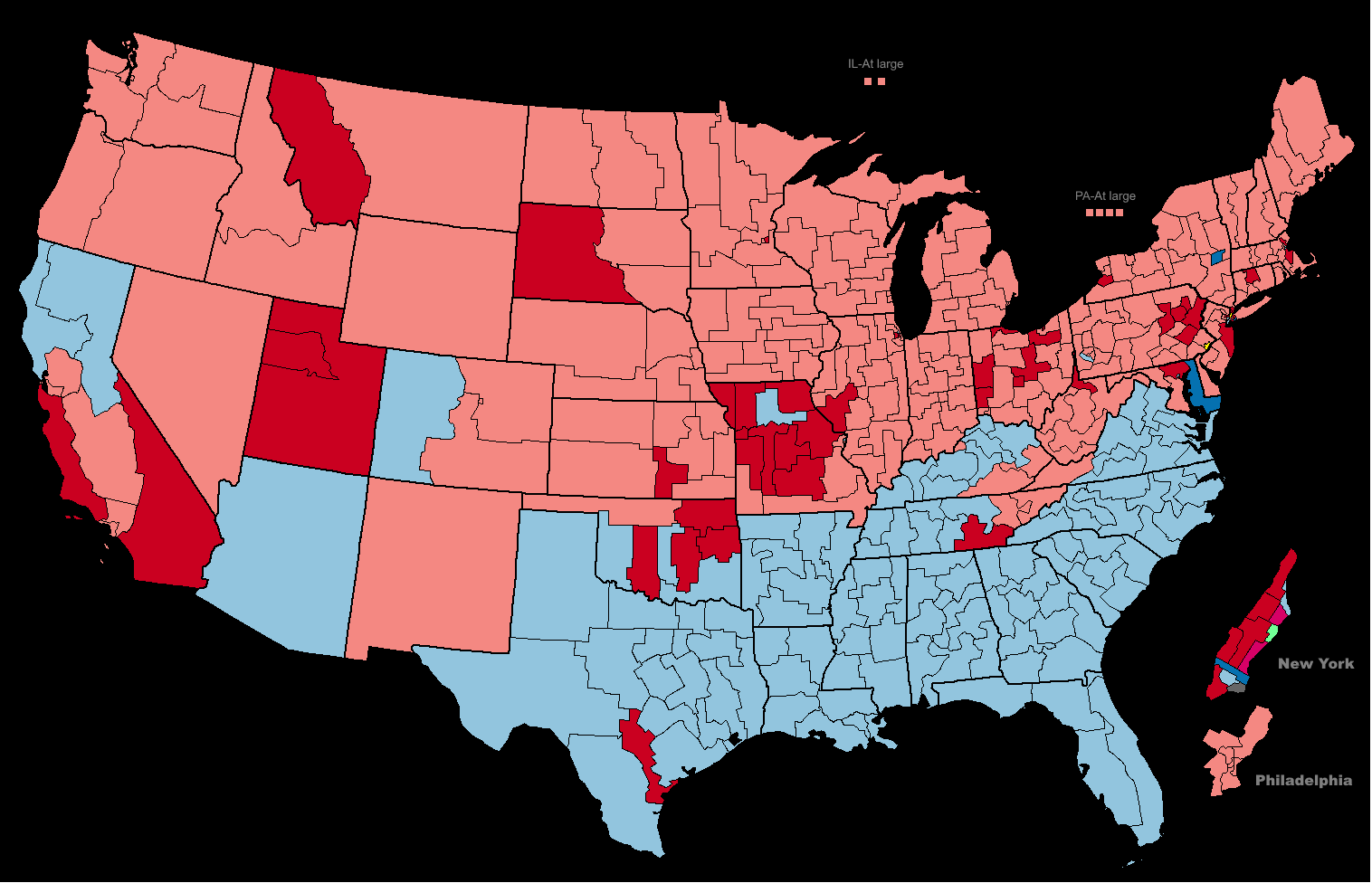

List formation varied between departments – in some places, IR and DA formed common lists with the Centre-Left instead of the Right; in some places, everyone teamed up against the SFIO list etc. Distinguishing the shares each party received in the popular vote is, therefore, quite impossible. I have tried to calculate the outcome for the three main blocs (Bloc National, Gauche Radicale, Socialists) nevertheless. Here are the figures, and by comparison their OTL results in brackets:

Bloc National: 51.9 % (53.4 %) of the popular vote; 372 (429) seats;

Gauche radicale: 23.4 % (20.9 %) of the popular vote; 137 (112) seats;

Socialists: 20.2 % (21.2 %) of the popular vote; 64 (68) seats.

Like IOTL, the outcome of the election was termed a “blue horizon”, not only because the centre-right parties were associated with that colour, but more importantly because the parliament was so full of former soldiers and officers of the Great War, who proudly attended the assembly in their blue uniforms.

Negotiations began immediately after the results were out. Broad and shifting coalitions would ensue from this outcome, too, as had been the case in the past decades, but the balance between the political forces had moved discernibly rightwards. In the PRRRS, the heated debate about foreign and social policy strategies continued. Among the organized socialist labour movement, though, the message of the 1919 general elections was that a divided house cannot stand. The chaos in Prussia, which happened around the same time and in which the Militant wing of the IRSDLP was involved in a leading position, further added to the combined onslaught of French publicized opinion, trade unions and other socialist parties against the PSIRT, which became ostracized and isolated and lost another portion of their meek followership, who returned into the SFIO’s fold. The new SFIO leadership, led by Blum, humbly drew the conclusion that now was the time to redefine their platform and unite its wings on a Party Congress, and from a more solid foundation seek electoral alliances with the Centre-Left in the future.

[1] He is a lot more popular ITTL without the perception that Germany “got away too easily” in Versailles, which caused the conservative press to deride him as “perds la victorie” = he who loses the victory. ITTL, Clemenceau oversaw the total dismemberment of Germany, French annexation of Alsace-Lorraine and the Saar, puppetisation of the Rhineland and to some extent Bavaria, creation of the EFP as a proxy for French interests all over the continent, presided over by a Frenchman. He might even get elected as the next President when both Chambers come together…?!

The political situation in Italy was dominated by the unsettling experience of the failed Italian Revolution. It had impressed and shaken every layer of society and all political forces. To give this update a focus, though, I shall concentrate on one political party, and one leading and founding figure within it, at first:

Luigi Sturzo and his Partito Popolare.

Political Catholicism in Italy, like in various other “classical liberal” political systems of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, had grown in opposition to secularist policies of the aforementioned liberal establishment, and over time increasingly also in rivalry to socialist forces, attempting to organize workers into Catholic instead of Marxist unions and promoting the “Catholic social model” as roughly outlined in the papal encyclical “

Rerum novarum”, which demanded fair relations between capital and labour, emphasized the role of families and communities in providing mutual help and solidarity, and condemned socialist attempts to overthrow private property.

Because of the papal boycott of the Italian nation-state and its political system, over a long period of time Italy did not have an equivalent party to the German Zentrum or the Austrian Christian Socials, though. In the absence of such a common platform, political Catholicism in Italy found many different channels and outlets: clerics spoke out on political matters, taking widely diverging positions from very conservative ones to the Catholic socialism of a

Romolo Murri. Among the laity, the

Azione Cattolica had begun to concentrate various Catholic social groups into a new movement.

As new popes saw the futility of attempting to boycott Italian electoral politics, the Catholic Electoral Union formed in 1906. Its relative lack of success was an important reason for the decision of its leaders to negotiate an electoral alliance with the Liberal Union in the 1913 elections instead, an alliance which became known as the

Gentiloni Pact.

Shaken by the experiences of the Great War and caught in the wave of politicization which washed over the entire continent, Italy’s political Catholics made another attempt at forming a political mass party after the war: the Partito Popolare Italiano (PPI). Under its roof, left- and right-wing oriented Catholics, so-called “Modernists” and “anti-Modernists”, those who had opposed the war and those who had not, those who agreed with the general tendency of the European Federation of Peace and those who considered it dangerous, gathered. Its leaders, Luigi Sturzo and

Alcide de Gasperi, both came from the party’s centre and attempted to lead the party into the centre stage of the kingdom’s political scene.

To the PPI, the outbreak of the Italian Revolution was a shock. The war between the classes, which the Catholic social movement had attempted to prevent with all their means, had apparently broken out. Both Red and Black revolutionaries were led by militant atheists and vowed to smash the Church’s role in society and the last vestiges of Christianity in the country of the Pope. [1] Among their ranks, there were thousands who, not long ago, had attended mass together with their neighbors on Sundays. Cities burned, men and women were killed in the streets, sectarian violence showing a shocking degree of aggression and dehumanization which certainly owed in no small part to the experiences so many Italians had made in the War. The avowed enemies of the Revolutionaries, in their blue shirts, were no less brutal and bloodthirsty, either, and their radical Integralism, which the Pope had already declared anathema five years ago, was gnawing away at the right wing of organized political Catholicism, just like the new Socialist Revolutionaries were breaking into the left flank of rural and traditionally pious segments of the population on whose electoral support the PPI had counted upon, agitating the peasantry and bringing them close to the verge of rebellion.

As the established parties struggled towards a response to the revolutionary challenge and various PPI leaders panicked, Don Luigi Sturzo kept a cool head. He saw a pivotal opportunity, and he seized it. Sturzo was one of the driving forces behind the negotiations in which very unlikely partners found together and agreed on a political, social, and economic reform agenda for the Kingdom of Italy, which would be the big sweet carrot in the strategy with which the anti-extremist forces sought to combat the Revolution, together with the stick of the use of large numbers of military police against the isolated last pockets of insurgents.

The reform pact behind which rallied Sturzo’s PPI as well as

Francesco Nitti’s anti-clerical

Radicals, the liberal-conservative

Liberal Union of

Giovanni Giolitti,

Sidney Sonnino,

Antonio Salandra and V

ittorio Emanuele Orlando as well as the newly formed [2] United Socialists of

Filippo Turati and

Ivanoe Bonomi and

Alessandro Scotti's moderate wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries [3], the Partito dei Contadini Italiani, officially carried the pompous title of “Patto per la Salvezza Nazionale è la Giustizia Sociale”. Popularly, it soon came to be called “Gran Alleanza”, the Great Alliance, for it included almost all Italian political forces, except for

Nicola Bombacci’s rump-PSI,

Amadeo Bordiga’s PSDRI [4], the Independent Socialists now led by

Michele Bianchi after Mussolini’s flight into exile, and the radical right-wingers of the ANI.

The adherents of the Gran Alleanza committed themselves to a shared program of agricultural, labour, economic, electoral, educational, cultural and constitutional reform in the legislative period to come – a great scheme for consensual changes in many different fields of society with which said society could be stabilised (after which everyone expected the members of the alliance to go different ways again). It would only have a chance to become reality if the parties of the Gran Alleanza received a very solid majority and stuck with it, if the majority of the unions and industrial associations, of the clergy, the Catholic Action and many other social groups, and not least of all King Vittorio Emanuele III. himself unanimously, unwaveringly, and persistently supported it.

Whether that will be the case remains to be seen – but the promise, together with the failure of the revolutionary alternative, exerted a massive appeal to the Italian electorate. It, together with the peculiarities of the Italian electoral system [5], caused the new Parliament to be utterly dominated by the parties of the Gran Alleanza, who consistently supported each other’s best-placed candidate in the second round:

- The PPI obtained 265 seats and became the strongest faction by far. Its undisputed leader and triumphant architect of the alliance, Don Sturzo, was expected to be nominated as the next head of government, tasked with pushing forward the ambitious reform agenda.

- The Liberal Union fell from 270 seats in 1913, in spite of the creation of new constituencies in the formerly Habsburg territories of the North, to 187 seats in 1919. Yet, this fall was by far not as horrible as many had expected. The electoral system and the Gran Alleanza had bought the grand old party of the Italian bourgeoisie another bit of time, as its equally grand old leader Giolitti well knew. Just like he himself, his party might not have many strong and powerful years ahead of itself. But they could finish their legacy by leaving a lasting imprint on the development of the country in the 20th century through their contribution to and influence of the reform agenda of the Gran Alleanza - and they had managed to stave off the revolution.

- The Radical Party fell from 62 to 55 seats;

- The left-agrarians of the Partito dei Contadini scored 47 seats, which wasn't overwhelming, but also not bad for such a young party, and it might just suffice for them to be able to compel their electoral partners to honor their promises of agricultural reform;

- The United Socialists, finally, obtained 31 seats, most of them only won by popularwell-known personalities, and not few of them only with bourgeois support in the second round against dissident socialist counter-candidates in the industrial cities of the North.

This brought the Gran Alleanza to a common total of 585 out of 654 seats.

Of the opposition, the PSI scored 39 seats, the ANI achieved 11 seats, and the Independent Socialists 3, while the PSDRI failed to get any of their candidates in over three dozen constituencies elected. 16 more parliamentarians were voted as independents or members of small, unaffiliated groups.

Under the given electoral system, the Italian Left paid a hefty price for its inner divisions, the failed revolution and sectarian violence. In the first round, the four major socialist parties (United Socialists, PSI, PSDRI and Independent Socialists) together had scored almost 40 %, but now they were left with less than 15 % of the seats, scattered between the coalition socialists and a bitterly divided opposition.

The Gran Alleanza had triumphed and achieved the super-majority it would need to push through its reforms. Within it, the new parties of the non-revolutionary left were much weaker than the Catholic PPI and the liberals. Italy’s middle classes – even those who did not particularly like the new hegemonial clerical party – sighed with relief.

[1] Just a quick reminder how different TTL’s “Independent Socialists” are from OTL’s Fascists

[2] During the Italian Revolution, Turati’s moderate wing of the Socialists, among them many of the party’s members of parliament, had finally split when the PSI leadership not only refused to distance itself clearly enough from “violent mob rule”, but also wanted no part in the negotiations for a state, social and economic reform in the framework of the Gran Alleanza. Split from their mother party, Turati’s group then united with another group who had split off a few years earlier, Ivanoe Bonomi’s Reformist Socialist Party.

[3] Giuseppe di Vittorio is extremely interesting and I will keep it in mind, but in 1919 he's still too young to lead any of the party factions, I thought.

[4] Given the disagreements between Bordiga and the Torinese IOTL, I suspected another schism might be in order. Bordiga is on the “Militant” wing of the IRSDLP, while Gramsci and Togliatti remain in the PSI because they do not share Bordiga’s rejection of bottom-up leadership by workers’ councils, even if unions exert an influence in them, in favour of paramilitarily organized “flying revolutionary columns”.

[5] All males above 21 as well as even under-21s who had served in the military received the suffrage in 1917 as per OTL. IOTL, though, the PSI and PPI separately pushed for proportional representation which they (rightly) thought would benefit them. ITTL, this is not the case, the PSI’s demands are ignored, and the Gran Alleanza makes the most of its pact’s overwhelming electoral force by keeping the pre-war single-member constitutency two-round voting system in place:

Each constituency elects one member of parliament. If no candidate obtains an absolute majority in the first round, then the two candidates with the highest numbers of votes duel in the second round, in which the candidate with more votes is elected.

The End of 1919, part 6: Trouble in America

1919 was a troubled year in the history of the United States of America. Domestically, the Seattle General Strike had marked only the beginning of a long series of strikes (in the coal and steel industries, in railways and, most unsettling to many, among the police) spiraling into violent conflicts between organized labour on the one hand, and the organs of law and order as well as private paramilitary organizations (Pinkertons, Baldwin-Felts etc.) hired by industrialists on the other hand. The violence of these class conflicts only superficially mirrored revolutionary models from Europe – for example when rebellious coal miners in West Virginia formed “workers councils” – but in truth, it had a long autochtonous history in the US. [1] Now they were exacerbated by the economic downturn caused by the conversion from war to peace-time production – and over a million demobilized soldiers returned into a contracting job market.

Segments of the press as well as the US Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, conjured up the spectre of chaos, anarchy and the collapse of the constitutional order in America. [2] Such a collapse and an establishment of socialism in the US was never very probable in 1919, to say the least – one reason for this being the fractured and disorganized state of the American Far Left and massive political divergences among the unions. The Socialist Party of America had never been very successful as a unifying political arm of the labour movement, and with its leader and presidential candidate Eugene Debs imprisoned, it underwent massive factional strife on its National Convention in August and ultimately radicalisation – but we’ll come to that in a minute. The unions were no better, with political enmities between the moderate AFL and the radical IWW, between two splinter products of the IWW, between the IWW and the WFM etc. preventing large solidaric action in protest of anti-labour violence, the curtailing of labour rights and coalition etc., let alone country-wide general strikes.

But on one level, the fears had a foundation in reality: while militant unions were not able to form a united front, their growing impatience caused new spikes in strike-related violence and deaths. And while there was certainly no broad conspiracy to overthrow the constitutional system, there were isolated bouts of political terrorism like the wave of mail bombs targeting politicians and industrialists, which shocked the nation in 1919. A group of Galleanist anarchists claimed responsibility for them, declaring them as “acts of revenge of the oppressed laboring classes”. [3]

Yet more violent than the clashes arising from labour strikes were racist pogroms. As IOTL, the amorphously pre-revolutionary atmosphere, combined with white suprematist racism of the time and the long-standing tradition of lynchings in the country, led to pogroms against African Americans in various places – with the reason varying as widely as striking white workers attacking African American strike-breakers in some places, to reactionary-minded mobs “retaliating” against perceivedly black aggressions behind which not few saw the consequences of “agitation of the negroes to rise up against order and civilization”. IOTL, probably around a thousand people died in the “Red Summer” of 1919. IOTL, most of them were African Americans.

ITTL, things begin to take a slightly different turn during the summer months of 1919. In July, when Italy is gripped by its (ultimately failed) Revolution, Palmer and the young head of his new “General Intelligence Division”, one J. Edgar Hoover, began to refocus their allegations of revolutionary subversion towards “Italian anarchist and syndicalist agitation”. Newspaper took to the new idea fast, and soon there were suspicions of “Galleanists” and “fascists” (which, here, most often meant militant Italian syndicalists) behind every Italian-speaking corner. Ethnically biased police raids and the apprehension of many Italian immigrants suspected of leftist leanings caused protest, of course, and in a massive over-reaction against such a protest, an anti-Italian mob began to target the suspicious minority in Boston, with the ethnic clashes lasting almost a week and killing hundreds. Another anti-Italian pogrom occurred in New Orleans, burning through the city while the state’s governor John M. Parker turned a blind eye.

And Italians would not remain the only Catholic group coming under fire in the heated, chaotic days of 1919. The Irish struggle for independence from Britain had a few socialists involved in it IOTL, too, but ITTL the contribution is more visible, with the emerging International Red Aid of the IRSDLP engaging heavily in the country and the rebels forming council structures inspired by the Russian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Italian and various German Revolutions. This more nuanced “leftist” hue of the Irish revolutionary struggle naturally had implications for Irish Americans and how they were viewed by others, too.

On its Emergency Congress in late August 1919, the Socialist Party of America was taken over, as it has been often claimed, by its radical wing. The “Regular” faction around Adolph Gerner and Julius Gerber, which had led the party hitherto while Eugene Debs was in prison, was replaced by a group whose superficial agenda was affiliation with the IRSDLP and rejection of a continued engagement for the Gorky-Thomas-Addams Plan (for the SPA Left Wing saw itself closer to the “Militant” and “Anti-Imperialist” current than to the theoreticians of Ultra-Imperialism). How little the new leadership from the “Left Wing” truly cared for the IRSDLP transpired only weeks later when delegation negotiations with Trotsky broke down – Trotsky did not want the Americans to tilt the emerging party’s balance towards Anti-Imperialism – and the new SPA leadership simply buried the idea of joining the IRSDLP quietly (contributing greatly to the latter's limitation on Europe in the Riga Congress). The composition of the new SPA leadership clearly showed that the driving force behind the mobilization of a left-wing majority on the convention was a coalition of the “

language federations” affiliated with the SPA, first and foremost of the Italian and German language federations, with socialists from Minnesota and New York of Irish background on the other hand. Where the old “Regular” strand of SPA policy – protest marches and an emphasis on electoral strategies – seemed bland and anaemic by 1919, the beleaguered “ethnic” socialists had now risen to the challenge of agitating for the formation of self-defense groups and militia and the “councilisation" of their neighborhoods, and now they were pushing the party towards a more militant stance and a more defiant opposition to the racist attacks like the one to which, in September 1919, the Irish community in the republic’s capital, Washington, was subjected to.

By the end of the year, violence was not subsiding at all, in spite of a wave of detentions and deportations of “anarchists”, “militant syndicalists” and “alien socialist insurgents” based on the prolonged Espionage Act of 1917, Sedition Act of 1918 as well as on the Immigration Act of 1918, and impatience began to grow in Congress. In this situation, Acting President Thomas Marshall chose to withdraw his support for Palmer’s policies, publicly commenting on Palmer “seeing red” [4].Marshall not only feared Palmer’s scheming to position himself in the limelight in the Democratic process of nominating a new presidential candidate in 1920, but also that his raids and his anti-Italian and anti-Irish rhetorics were driving these important constituencies further away from the Democrats and into the arms of the Socialists. He countered Palmer’s “judicial overreach” with a proposal for strengthening the National Guard.

Palmer knew what to do, though. If Marshall attempted to sideline him and sabotage his efforts to build up a strong intelligence agency, then there was a camp with which he could align. Ever since Woodrow Wilson’s stroke in Paris and his near-total incapacitation, the federal government had become split between a faction who supported Marshall as Acting President and a policy shift away from what the leaders of various ministeries considered as failed “Wilsonian” policies on the one hand, and the opposite camp which remained loyal to Wilson and his agenda. Marshall’s closest ally was Foreign Secretary Robert Lansing – together, they had begun to steer US foreign policy away from Wilson’s focus on an international covenant of peace and multilateral free trade agreements, which they saw as having led nowhere and practically only meant continuedly high military expenditures in overseas adventures at the side of a British ally who in turn often openly pursued goals diametrically opposed to American interests (like the new Conservative and Unionist Prime Minister Bonar Law’s tariff policy of “imperial preference” [5]). Instead, Marshall and Lansing sought to conclude bilateral agreements – with Japan on naval limitations, a coordinated China policy and free Pacific trade; with the UoE on a “revised repayment and refinancing scheme” for the Union’s unbearable burden of debt in exchange for US involvement in building up the (legally socialised) oil industry in the UoE's Central Asian republics etc.

Opposition to Marshall within the cabinet came from Treasure Secretary Carter Glass, who denounced the negotiated proposals, even before they were concluded, as “bowing to Asians” and a squandering of American wealth and endangering of the confidence which the young and frail federal financial institutions so dearly needed, but also from War Secretary Baker and Navy Secretary Daniels. Outside the cabinet, William Gibbs McAdoo, by far the most popular “Wilsonian”, fired in the same general direction. As 1919 turned into 1920, they also had Attorney General Palmer on their side now, and this powerful cabbal thwarted Marshall’s counter-proposal for strengthening the National Guard, denouncing it as “infringing on the states’ rights”.

[1] To those unfamiliar with them, I recommend reading up on the Coal Wars, on Haymarket, Coeur d’Alene, the Colorado Labor Wars etc. I, for one, had not been aware of it before I read

@Iggies ’ wonderfully written TL

“The Glowing Dream” and did some research to contrast and compare his TL to OTL history.

[2] That is different from the spectre they conjured up IOTL. The Bolshevik spectre was supposed to be a centrally organized, quasi-conspiratorial attempt to intentionally overthrow the existing order and replace it with the dictatorship of the vanguard party of the proletariat, and Palmer as well as parts of the press repeatedly suspected that alien Bolshevik elements (primarily recent Eastern European Jewish immigrants) sought to agitate “the negroes”. The perceived danger of TTL is more amorphous, more decentralized, and it is associated with a different minority, as we shall see.

[3] All of which is entirely OTL.

[4] IOTL, those were Wilson’s words, and they have been interpreted in different ways…

[5] I did not mention this one, but I guess you saw it coming: the Coalition has broken apart years earlier than IOTL, and Bonar Law is heading a new all-Tory government.

The End of 1919, part 7: Britain and the Empire

Neither Britain’s geopolitical position, nor the self-concepts of its political elites allowed for a surge of isolationism like the one which washed over the US after the horrible sacrifices of the Great War. But public opinion in Britain, too, developed, over the course of 1919, the view that, while the war had been won, the peace had more or less been lost. Labour unrest was widespread. Violence and anarchy in Ireland were getting worse by the week, in spite of the government’s combined strategies of repression and concessions (the latter still aimed at implementing Home Rule as laid down by the 1914 bill). Apart from Ireland, British and colonial forces were fighting insurgents in as many places as Egypt, Turkey, Kurdistan, Iran, and Afghanistan at once. At the Paris Peace Conference, Britain had obtained nothing – all its gains in colonies, in Germany and in the Middle East had been obtained through separate agreements – and now saw itself excluded from a comprehensive continental alliance in the form of the EFP.

David Lloyd George sought to counterbalance the failure of the Paris Peace Conference by creating a “League for Peace and Prosperity”, which was basically the British Empire and its old and new “protected states” (from Hannover to Arabia) in a fashionable new dress, with the de facto complete independence of the Dominions formalized and balanced by a mutual commitment to come to each other’s defense in case of attacks by outsiders. Close economic co-operation was to be part of the deal, too (which allowed Northern Germany to profit from the lifting of the sea blockade (and from there, the rest of Germany profited, too, as the new inner-German borders were generally open).

While this latter idea was popular on the larger British isle, especially among the Conservatives, too, as it came close to the idea of “imperial preference” which was favoured by a majority of Tory MPs and members of government, the former was generally not. As the war-time censorship of the press was lifted and demobilized soldiers returned to their families with tales of the horrors of Flanders (and Gallipoli, and many other such places), the prospect of frequent military interventions was not popular at all. Neither in England, Scotland and Wales, nor in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa or elsewhere.

After initial momentum, Lloyd George’s league idea ran into more and more obstacles as the details were negotiated with the Dominions. At the same time, the violence in Ireland was always present in the national consciousness: the [greater than OTL] parliamentary presence of the Irish Parliamentary Party in Westminster made sure that all the gruesome details of ruthless military and “policing” operations and civilian suffering in Ireland were made public and loudly lamented by the faction led by John Dillon. Ireland was increasingly turning into a millstone around Lloyd George’s neck, dragging down his popularity.

It is not very surprising, thus, that Lloyd George sought to rid himself of this problem as fast as possible. The IPP demanded the immediate enactment of the Home Rule provisions, and Lloyd George was more than willing to grant it. Preparations for elections to separate Southern and Northern Irish Assemblies were begun.

That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The camel was, in this case, specifically Andrew Bonar Law, leader of the House of Commons and the Conservative Party and a particularly fervent Unionist. He, who had sworn in 1912 that “never under any circumstances will we submit to Home Rule!”, now gathered a large number of Conservative MPs with the aim of sabotaging the Home Rule implementation and the league idea as well as bringing down the Coalition government. While various Conservative members of the government and of the party’s leadership around Austen Chamberlain did not consent and would have preferred to continue the Coalition, the refusal of a Conservative majority to support the provisions for the implementation of Irish Home Rule created a fait accompli when Lloyd George stepped down as Prime Minister.

Bonar Law then took the reins and formed a Cabinet of Conservatives and Unionists who supported his envisioned policy changes. Himself, Law summed this shift in the political agenda up as “a new focus”. While he continued the negotiations over “imperial preference” in commerce, the idea of a British-led league was buried and replaced by negotiations for bilateral treaties (Anglo-Syrian, Anglo-Egyptian and renewed Anglo-Iranian and Anglo-Japanese treaties were all prepared, but not concluded yet in 1919). Overall, Law preferred focusing on three crises while reducing British engagement elsewhere: Ireland, India, and the security of British trade routes with India through Arabian countries. In this readjustment of foreign policy, Law found competent assistance in his Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, who replaced Balfour. Curzon took the deliberations over Egypt’s future out of Milner’s hands and directly into his own; likewise, he urged cautious co-operation by the Zionists with the newly crowned King Faisal and submission to his suzerainty over the emerging Jewish Autonomy.

While Law’s new Arabian policies were less reluctant to leave the Arabians to govern themselves as long as British access to oil and sea trade routes were safeguarded, in Ireland his cabinet turned away from the implementation of Home Rule as long as, as Law put it in a speech, “any election in Southern Ireland would only bring us an assembly of nationalist insurgents, socialists and terrorists, and the permanent rupture of the island”. Instead, military involvement was stepped up with forces from various other theatres (not least from Turkey) being relocated to Ireland in order to suppress the Irish Republican Army’s “flying columns” and smoke out nationalist and socialist rebellion on the smaller British isle for good.

Like many parts of the world,

Canada was facing economic contraction, unemployment, social tensions, the return of disillusioned veterans, and labour conflicts. One particularly bloody example of the latter was the

Winnipeg General Strike of May 1919. The country was governed by the conservative

Arthur Meighen who had formed not only a “Union government” of conscription supporters, but also a united “National Liberal and Conservative Party”. Like IOTL, Meighen’s government and party are losing a lot of popular support throughout 1919, and various Liberal politicians, who had joined the Union government, were returning to the Liberal Party, who chose to maintain its course by electing Willian Lyon Mackenzie King as its new leader on

its convention.

Already IOTL, Meighen’s government had raised and introduced new tariffs – among other things – to finance the war effort. Keeping them in place after the war, too, (instead of e.g. more progressive income taxation) was rather unpopular, surprisingly especially among the farming population (also like IOTL). ITTL, even Bonar Law’s new British government’s

plans for empire-wide protectionist policies certainly accentuate this conflict. Therefore, the spectacular bashing of Ontario’s conservatives in the

provincial elections of 1919 and their replacement in the province’s government by a coalition of the new populist-agrarian United Farmers’ Organization with a handful of elected Labour parliamentarians (Canada’s organized labour became antagonized by Meighen’s bloody crackdown in Winnipeg, just like IOTL) is even more spectacular ITTL. Such left-agrarian groups and parties, who would later form the backbone of the Progressive Party, are springing up across Canada’s provinces. In Quebec, which is a bit of an exemption to this rule, the conservatives (who had always been weak here) are now utterly marginalized in a provincial assembly completely dominated by Liberals and “Independent Liberals”, in which also the first handful of Labour parliamentarians take their seats. (

Like IOTL.)

So, altogether not much is changed in Canada. There are still two years before a new national election. What is going to be interesting is how Canada’s emerging agrarian populists, Labour politicians and unions are going to interact – if they form a broad-tent alliance of the centre-left, or if they go separate paths like IOTL, what becomes of the “

Ginger Group” etc. … This probably cannot be viewed separately from whether there is a comparable situation in the US and how it develops there.

The situation of agricultural producers at the time, across the globe, was one of abrupt changes indeed, and

Australia was no exception. Here, though, 1919 brought

new elections, in which the emerging “Country Party” is already contending in various regions. Their overall results are unlikely to be changed: the Nationalist Party, which had been formed during the war as a fusion of the old (conservative) Liberal Party and the pro-war wing of the Labour Party, is still going to win it because there is no new momentum strong enough to propel the independent Labour Party or anybody else into a position to steal this victory from

Billy Hughes. Even if Hughes does not come back from Paris triumphantly (Australia gains the same territories, but only through a separate treaty with Japan, and there hasn’t yet been any broad international recognition of it yet, even though there isn’t any outspoken opposition, either), the sheer breadth of the Nationalist Party and its active, interventionist economic policies which helped ease Australia’s economic conversion troubles, are likely to secure it a victory in TTL’s 1919, too.

I only envision one slight change in Australian politics as compared to OTL: ITTL, the various regional Country Parties attended the Green International’s Congress in Bucharest as observers, and various delegates came back with a very positive view on an (economically strong) state supporting infrastructural development projects on a large territorial scale, as they were supported by both the Alkio and the pro-Russian wings of the Internationale. Consequently, I see the Country Party throwing more support behind the

1919 referenda while IOTL it was somewhere between opposed and lukewarm. The margins were very narrow IOTL already, so only a few voters changing their minds compared to OTL should suffice to give the federal government of Australia farther-reaching legislative powers over economic matters and to nationalize various natural monopolies.

The End of 1919 in China

The “Constitutional Protection War” of 1918 left China factually divided into at least two loose blocs: a Northern one where the Anhui clique stayed in the centre of power in Beijing, and the Southern Guangzhou government. Both camps were not at all solid and homogeneous, of course: the course of the war had shown that factual power rested with various armed factions whose loyalty was first and foremost to their respective military leaders (we use to call them “warlords”) and less to either government in Guangzhou or Beijing. In both camps, ambitious politicians held very different ideas about China’s future, and without properly functioning constitutional processes of decision-making, negotiation and compromise have been replaced by military alliance-building. Throughout 1919, a new factor entered the equation (or rather, an already existing one multiplied its importance): a strong urban popular protest movement against the policies of Duan Qirui and his Anhui clique, centered around Beijing, but whose political agenda soon came to encompass a different vision for China’s future, taking inspiration from successful revolutions elsewhere.

So far, all is identical with OTL. If we look closer at what happens in the North and South respectively, though, divergences begin to become apparent by mid-1919: in the North, Duan Qirui has not been able to deflect the nationalist anger of the *May Fourth Movement by invading and conquering Mongolia because of the latter’s pact with the UoE. His position is shakier than IOTL, and the *May Fourth Movement is also slightly stronger because the political impulses which especially its more radical leaders have received from TTL’s Russian Revolution are more inductive of participation in broad-tent revolutionary alliances instead of OTL’s Lenin-inspired insistence on a vanguard party with a uniform but very foreign (and in need of massive “translation”) doctrine. In the South, Sun Yat-Sen’s position as generalissimo versus the various Southern military leaders, especially of the Old Guangxi clique, is slightly stronger because Kerensky’s Foreign Office is providing more and more assistance in various forms. (As so often with Kerensky’s foreign policies ITTL, this is only in part motivated by real or imagined ideological overlaps, and in much larger part by geopolitical considerations. IOTL, all great powers had their “clients” or “pawns” in Warlord China – only Soviet Russia, during its civil war, had neither the nerve nor the means nor the inspiration to meddle in China, too, and only later began its shifting course between supporting a “unitary” KMT and supporting a CCP independent of it. ITTL, the UoE’s absence from the Chinese stage is much shorter, and by 1919, Kerensky has chosen who should owe the UoE a favour.)

As a consequence, Duan Qirui is in more dire need to act quickly in some way which would stabilise his and the Anhui clique’s power. His only secure military powerbase is the War Participation Army. Duan’s move, thus, is almost inevitable: he cuts all negotiations between North and South about a lasting political settlement (or so he thinks!), sets the War Participation Army in march and calls on all loyal Beiyang forces to march against the Southern rebels once again, aiming to finish the job which had been stopped half-way in 1918.

He has miscalculated the amount of power and influence he wields on the various provincial factions, though. Just like Wu Peifu stopped the 1918 campaign in its tracks, now a large conspiratorial alliance emerges with the aim to stop Duan and unseat the Anhui clique. IOTL, a similar anti-Anhui coalition is formed with Cao Kun at its centre, bringing the Zhili clique to prominence in 1920ff. ITTL, it is Cheng Jiongming and two Southern military leaders, Tang Jiyao and Lu Rongting, who took the initiative by offering Wu Peifu, Zhang Zuolin and various other local warlords recognition of their far-reaching autonomy in a new “truly democratic”, federalized Chinese Republic if they turned against Duan Qirui and recognized Sun Yat-Sen’s transitional role as Generalissimo until the conditions for fair elections are restored by eliminating “Anhui corruption”.

And so, all over China, troops are set in motion, but instead of united Beiyang forces crushing the Guangzhou government, virtually everyone turned against Duan Qirui’s War Participation Army, scattering it to the winds. As Duan Qirui’s powerbase evaporated, he fled Beijing with a group of close allies on a ship to Japan.

In Beijing, the temporary power void opened the floodgates for a wide and heterogeneous array of revolutionaries to take control, with “students’ councils” and “workers’ councils” and even “merchants’ councils” forming, defying the authorities of the Beiyang ministeries and forming a “Supreme Council” led by a triumvirate of Cai Yuanpei, Chen Duxiu, and Zhu Qianzhi (socially, this is a very lopsided and academic trio; politically, they cover the breadth from liberal nationalism over the new “Chinese Socialist Revolutionary Party” to anarchism).

Throughout autumn and into the winter of 1919/20, the co-existence of all these various groups, institutions and movements all claiming political authority and legitimacy to oversee the process of reforming the country’s institutions and organizing free and fair elections, turned out to be a growing challenge and a powderkeg. The position of Sun Yat-Sen, who aimed to push forward an agenda of centralization and military as well as agrarian reforms, soon proved paradoxical: almost the entire country overtly bowed to him and his authority as “Generalissimo”. His real power, though, had not grown much. A dangerous threat to the existence of his “Chinese Revolutionary Party” (not to be confused with the above-mentioned, Beijing-centered and more left-leaning new “Chinese SR Party”) had been removed, but China was by no means united under Sun Yat-Sen’s leadership. Even with regards to the processual details of new elections, any proposition was far from being consensually accepted: Sun Yat-Sen and many who were more conservative than him insisted on sticking with the provisions of the 1913 constitutions; the “Beijing Soviet” (if we want to call it this way, perhaps overaccentuating its role with the analogy to the Petrograd Soviet in the early Russian Revolution) suggested to take some inspiration from the UoE’s dual power and revolutionary soviet oversight over the process of reconstitutionalization. And, factually most importantly, the various warlords insisted that they be let alone to organize things their way in “their” regions, finding a legitimatory framework in the propositions of Sun’s formerly close political ally Chen Jiongming, who has proposed a new “federal” outlook for China (also claiming inspiration by the UoE’s constitution).