Some comments on Germany in May/June 1919:

Baden and Württemberg look entirely different. Württemberg’s King Wilhelm had been skeptical of the Great War from the start, the kingdom had enacted universal male suffrage for the second chamber of the Landstände already in the constitutional reform of 1906, and the monarch enjoyed popularity far into the liberal and social-democratic segments of the population. Once the great wave of reforms (to keep up popular support for the war) has been announced and in part started in Berlin in 1918, I see no reason whatsoever why Württemberg would not have taken a leading position again here. Female suffrage, a reform of the electoral constituencies, the inclusion of social rights in the constitution, and the reduction of the first chamber to a merely ceremonial role all seem plausible effects of the great war and the worldwide political climate of the moment to me, and they would be certainly sufficient to defang any revolutionary elements among Württemberg’s socialists. Therefore, Württemberg shall remain a (now parliamentary) monarchy. Lang läbe d’r König Wilhelm!

Württemberg becomes occupied only for a short period of time, by a very small French presence in the North and another very small Italian presence in the South. If Württemberg fully demobilizes its army, which I have no doubt that it will, then these troops are probably gone sooner rather than later – with the latest point in time probably around when the Württembergian government signs Versailles 2.0.

With regards to national politics, I expect Württemberg’s Landstände to support the Vorparlament, where one of theirs, Matthias Erzberger, is leading the Zentrum’s faction and redrawing the party’s national political agenda, while both Württembergian Zentrum, Demokratische Volkspartei [left-liberal], SPD and USPD will calculate coolly what compliance with which foreign power over matters of how Württemberg should position itself in the questions of a new German constitution and of Versailles 2.0 shall bring for the little kingdom. They will have diverging opinions on these matters, but none of this is approaching the civil war level of their Bavarian neighbors, who are going to serve as the deterring example for our solid Swabians. This also answers the question of Württemberg’s relation to the council movement: worker councils, particularly strong in Stuttgart and Heilbronn, will not be forcibly dispersed and they’re certainly able to send delegates to Elberfeld. But any major disruptive economic transformation in the kingdom is probably going to be negotiated away – which might corroborate Stuttgart’s and Heilbronn’s positions as the cities with the most well-to-do workforce within Germany (which doesn’t mean a lot in 1919, to be fair).

In Baden, a similar development could take place belatedly after the resumption of hostilities. One requirement for saving the monarchy here is removing Friedrich II. in favour of his son Max. This could occur when hostilities resume. Friedrich II. could be in favour of attempting to resist the French – and then be silently pushed to the side by both the Badenblock coalition and the Zentrum in favour of liberal and pragmatic Max. Baden is still going to be overrun by French forces, although probably only towards the very end in this scenario because Baden isn’t high up on the list of military priorities (it’s going to end up French-controlled anyway, everbody knows). Max has good OTL credentials as a reformer, and I’m sure he could have worked well together with the “Badenblock” coalition of Social Democrats and liberals and enacted reforms which go beyond those of 1904. Baden remains a grand duchy, thus. It probably needs to demilitarize completely and let the French rove freely. As for how future Badish governments could develop, I have not yet made up my mind. The council movement is active primarily in Karlsruhe; the rest of the country has been historically dominated by militant liberals, with an electorally strong Zentrum seeing itself shut out of confessionally polarized politics. The proximity to France isn’t going to weaken Baden’s militant stance against the power of the Catholic church, I suppose – although positions with regards to Versailles 2.0 etc. could change this and cause realignments. Like in Bavaria and Württemberg, overtly nationalist parties are going to be forbidden, and the French are certainly going to help in smoking out any pockets of Heimatwehr resistance.

In Saxony, the Revolution had already driven off the Wettin monarchs and installed a Free People’s State. Its USPD-led government has, in turn, been attacked by Prussian forces after the Bundesrat had declared imperial execution against Saxony. But Saxony had never been pacified. It’s seen a several month-long civil war in the spring of 1919, which in the end was decided by Luxemburg’s successful mobilization in neighboring Gotha and invading Czechoslovak forces. Even before Hindenburg’s surrender, the Revolution has triumphed in Eisenach, Erfurt, Dessau, Gera and other industrial cities in the region. In some places, workers’ councils are dominated by the USPD, in others by Luxemburg’s new IRSD (the backbone of which form the remnants of the old Spartakist left wing of the USPD, joined by new radical groups). In spite of differences, the various revolutionaries form a common Workers’ Soviet of Saxony and Thuringia and send delegates to the German Congress of Workers’ Soviets. The supreme soviet of Red Saxony is situated, once again, in Leipzig.

It does not control all Saxon and Thuringian statelets, though, and only parts of the Prussian province of Saxony in addition. At first, anti-socialist opposition is divided and overwhelmed and without a plan. But even spontaneous opposition throws wrenches into the consolidation of Red Mega-Saxony. In Gera, for example, USPD-aligned revolutionaries have forced Heinrich XXVII. to abdicate as prince of both Reuß jüngere Linie and Reuß ältere Linie, and declared that all state functions are temporarily taken over by the councils (aligned to Leipzig) until a constituent assembly is elected. But while they soon manage to keep things running smoothly again in Gera, a centre of textile industry and a beating heart of the labour movement, they have little power projection into even the rural Southern reaches of the two principalities – and in reaction, on June 3rd, the old Landtag in Greiz declared that public administration in the former principality of Reuß ältere Linie would be overseen by them, not by any workers’ council, and they decided to throw in their lot with the Frankfurt Vorparlament to prepare the ground for elections to a constituent assembly, delegating one from among their rank to represent their little statelet in Frankfurt. Similar developments took place in the Duchy of Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, where Gotha is a revolutionary stronghold of Luxemburg’s IRSD, but Duke Carl Eduard was able to flee unobstructedly to Coburg. Likewise, in the Grand Duchy of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, Eisenach and Apolda fell into the hands of the revolutionaries, but in quiet Weimar, Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst still sits unobstructedly and even takes the initiative into his own hands by calling new elections for the grand duchy’s Landtag and seeking contact with the British military administration farther to the North in order to avoid being dethroned and seeing his entire grand duchy slide into radical socialism. Other principalities (both Schwarzburgs, the Duchies of Sachsen-Meiningen and of Sachsen-Altenburg) are also relatively unaffected by the red wave at first – on the other hand, Erfurt, which is legally in Prussia, is completely controlled by socialist revolutionaries.

The British don’t come to the aid of threatened monarchs so far South, though – the Saxon and Thuringian principalities are within the Czechoslovak occupation zone. But Czechoslovak military presence is sparse; they do not have the numbers to occupy a large territory. Nor are they interested in staying indefinitely – Masaryk’s government is desperately short of funds (like most other governments, too). Czechoslovakia’s strategic aims had been a) to remove the threat of a powerful Germany which might reclaim the Sudetenland from them, and b) to appear as a strong and reliable ally and important power in the concert of the EFP. Both of these have been achieved with their “joyful ride” towards Berlin and their formulation of a common new draft with the UoE for a peace treaty with many small Germanies (while the British and Americans still hold on to the idea of one German government which could shoulder this responsibility, which they hope to resuscitate through the Constituent Assembly to be elected). This draft envisions Greater Saxony and Thuringia as an “EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development” – which combines multi-national oversight, including a smaller Czechoslovak contingent, with explicit openness towards the possibilities of socialist experiments, but also towards a semi-sovereign statelet of their own for the Slavic-speaking Lusatian Sorbs of formerly Royal Saxony and Prussia’s adjacent provinces. (Sorbian rights come in a distant third place on Masaryk’s list of priorities, but still. Remember that while Masaryk is a bourgeois liberal nationalist, the Czechoslovak government overall has no anti-socialist leanings whatsover – they are one of the UoE’s closest allies, and there are moderate socialist parties in the coalition which governs the young country.)

After a few weeks, the Czechoslovaks, and more importantly: their UoE allies, observe with great concern that the non-Leipzig-aligned pockets are serving as bases into which remnants of nationalist Heimatwehren retreat and where they form anew, their ranks swelling with people opposed to Luxemburg’s radical socialist vision. Decisions are taken therefore to orchestrate a “revolutionary wave”, aided by the two EFP powers present in the region, to wash over the last remnants of the old order. In the end, the old tiered parliaments are dissolved everywhere and the Grand Duke of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, the Duke of Sachsen-Meiningen, the Duke of Anhalt, the Duke of Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, the Duke of Sachsen-Altenburg, and the Princes of the two Schwarzburgs and Reuß’ are all removed, and not only their domains and castles, but also those of most other nobles are plundered by revolutionary hordes, partitioned or opened for the public to hunt and poach in, and placed under the military jurisdiction of what, in late July, becomes the Governing Council of the EFP Mandate over Saxony and Thuringia. Saxony and Thuringia have become red strongholds.

Prussia’s old parliament is dissolved. In the place of its resigned government, an Allied Council for the Administration of Prussia is installed. Its provinces begin to unravel: a Rheinische Republik is established with a new constitution (no military, full sovereignty). The Saxon province, as mentioned, is partly controlled by Red Saxony and merged into an EFP Mandate. Another major centre of socialist revolution in former Prussia is the Ruhr region – here, by early June, most cities have come under the soviet control, and here is the beating heart of Germany’s socialist revolution, embodied in the Elberfeld Congress. The Red Ruhr is no monolith, either, though: it has International Communists, USPD, and the anarcho-syndicalist FAU, who can actually mobilise the largest number of militant supporters. In the Kerensky-Benes draft for Versailles 2.0, the Ruhr Industrial Region is marked as an EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development, too – which means that the council socialists can manage internal affairs for the time being as they see fit, as long as they do not put up any resistance to the military occupation by the French and Belgians.

The same EFP structure is proposed for Hesse, too, from Prussian Bad Karlshafen in the North to Grand Ducal Worms in the South. Here, there is no hegemony of socialist groups – instead, there are ongoing small-scale clashes between a broader revolutionary coalition (left-liberals and various socialists), supported by France, and remnants of the Heimatwehren (the French had been so busy to hurry towards Berlin, too, that they had not been very thorough in capturing, disarming and detaining von Wetter’s army, so some remnants are still left, joined by new voluntaries who oppose the radical change which is gripping Hesse’s Western and Eastern neighbors). Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig is still in Darmstadt, but actual power is exerted mostly by the French. French military occupation in Hesse is playing a duplicitious game: they are hosting and offering safety and protection to the Vorparlament in Frankfurt, while also supporting militant groups who would much rather have the transitional process being overseen by workers’ councils, and while exerting pressure on the Rhenish Republic to take as distanced a stance towards any vision of re-unified Germany as possible and obstruct all processes by which a concentration of the powers now in the hands of the various fission products of the empire could occur. If Versailles 2.0 becomes reality, there will probably be elections for a unified Hessian Landtag (for the Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau together with the former grand duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt), and if this happens, I don’t see it adopting anything other than a republican constitution. Heimatwehr resistance in Hesse is not something which couldn’t be eradicated, or at least reduced to dispersed terrorist cells, in a couple of months.

The security situation is entirely different in the East – i.e. in Pommerania, Silesia, and West and East Prussia. Here, large numbers of armed anti-Russian, anti-Polish, anti-socialist, anti-republican, anti-democratic, ultra-nationalist groups are still roaming. The Vinetabund is just one embodiment of this trend. This is a problem the UoE must deal with with only Polish “help” – and the Poles are only ever really helpful where they are granted full incorporation of a region into their emerging republic. This is going to be one motive why a revised Kerensky-Benes draft for Versailles 2.0 is going to award yet more German territory to Poland than the map I’ve shown you which depicted the negotiations in February/March. We’re talking about all of West Prussia, most of Upper Silesia, and yet more of Pommerania and East Prussia. Only this leaves the UoE with a challenge it can tackle with the limited forces that are politically feasible to maintain in East Germany. Like Danzig, the remaining territories designated not to become Polish are proposed to be fused into one EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development. Only here, the UoE has very little grassroots structures to build their regime change on. That does not mean they can’t create them – but that would take quite a bit of political genius. To the Russian political eye, “Germany” is an advanced industrialised nation, different from their rural self. It takes a bit to realize that East Elbia is socially and economically not too dissimilar to the former Russian Empire: a landed and military aristocracy ruling over an impoverished peasantry from their manors, producing cash crops with the cheapest available workforce. Once they realize this, the answer is easy: mobilise the dependent peasantry and sharecropping proletariat by enacting a land reform, a process in which peasant councils are formed which can serve as the backbone of a new socialist democracy closely aligned to the UoE. (The towns are more difficult, I admit – but the towns were and would be leaning Social Democratic IOTL, so the big question would be whether such a policy could somehow dissect the SPD from the idea of German unity and sovereignty to which it is quite closely wed. But I haven’t decided whether this course of action is going to take place at all – it would not be bloodless, to be sure, but all alternatives would be the UoE’s early Vietnam. It is vital for them to understand that they must drive a wedge between the German Junkers and their German underlings in East Elba. If they weld them together instead, they’re fried. Handing over territory to the Poles is one recipe for welding the two together in nationalist fervor. The problem is, it’s such a temptingly easy way out. What do you think the UoE will do in East Elbia?

And that’s not all the carving that’s being done to Prussia. Sorbian Lusatia has already been mentioned – most of it lies in Prussia, so if it gets singled out for “national self-determination”, that’s yet more amputations.

Oh, and Berlin. Berlin must be controlled by all Entente powers together, even if their Entente is not too cordial anymore. It’s probably moving towards a status as a free city.

Which leaves those parts of Brandenburg, Hannover, Schleswig-Holstein and Westphalia which are occupied (or earmarked for occupation) by Anglo-American forces. I have finally made up my mind about the US, and I will disclose this and how it affects British policy in the next update, too. Long story short, though: the British will see the writing on the wall and make sure they have some client states in Germany, too. Would they weld Schleswig-Holstein, Hannover, Westphalia, and “their” parts of Brandenburg and Northern Saxony together into a new “rump Western Former Prussia” or perhaps a “Northern German Republic”? I’m not sure – they could just let each province transform into an independent republic. What I’m pretty sure about is that Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck maintain their status as free cities, and that quiet Mecklenburg (both grand duchies unified, Friedrich Franz IV. was administering Strelitz, too, anyway after Adolf Friedrich’s suicide) remains a Grand Duchy, albeit probably with a more parliamentary constitution. Friedrich Franz was neither anti-parliamentary, nor was he particularly happy with the expansionist war plans. Oldenburg, on the other hand, is ripe for republicanisation or absorption into Hannover, even under British control, given its Grand Duke Friedrich August’s militarist stance and his own unpopularity.

Given that even in the British zone of influence, there is a real gore of weird boundaries and tiny statelets like Waldeck-Pyrmont, Lippe, Schaumburg etc., the most logical solution would be some degree of territorial consolidation / clean-up, but I’m not sure how this could be done without dethroning all monarchs, and even then it took the Nazis and another World War to remove these relics of the Medieval HRE from Germany’s map. The alternative is at least a zone of free commerce and travel (a new Zollverein) – ideally, this would be something legislated by a Constituent Assembly…. If not, its absence would be a pestering sore and things would not work out at all for the tiny states as independent entitites.

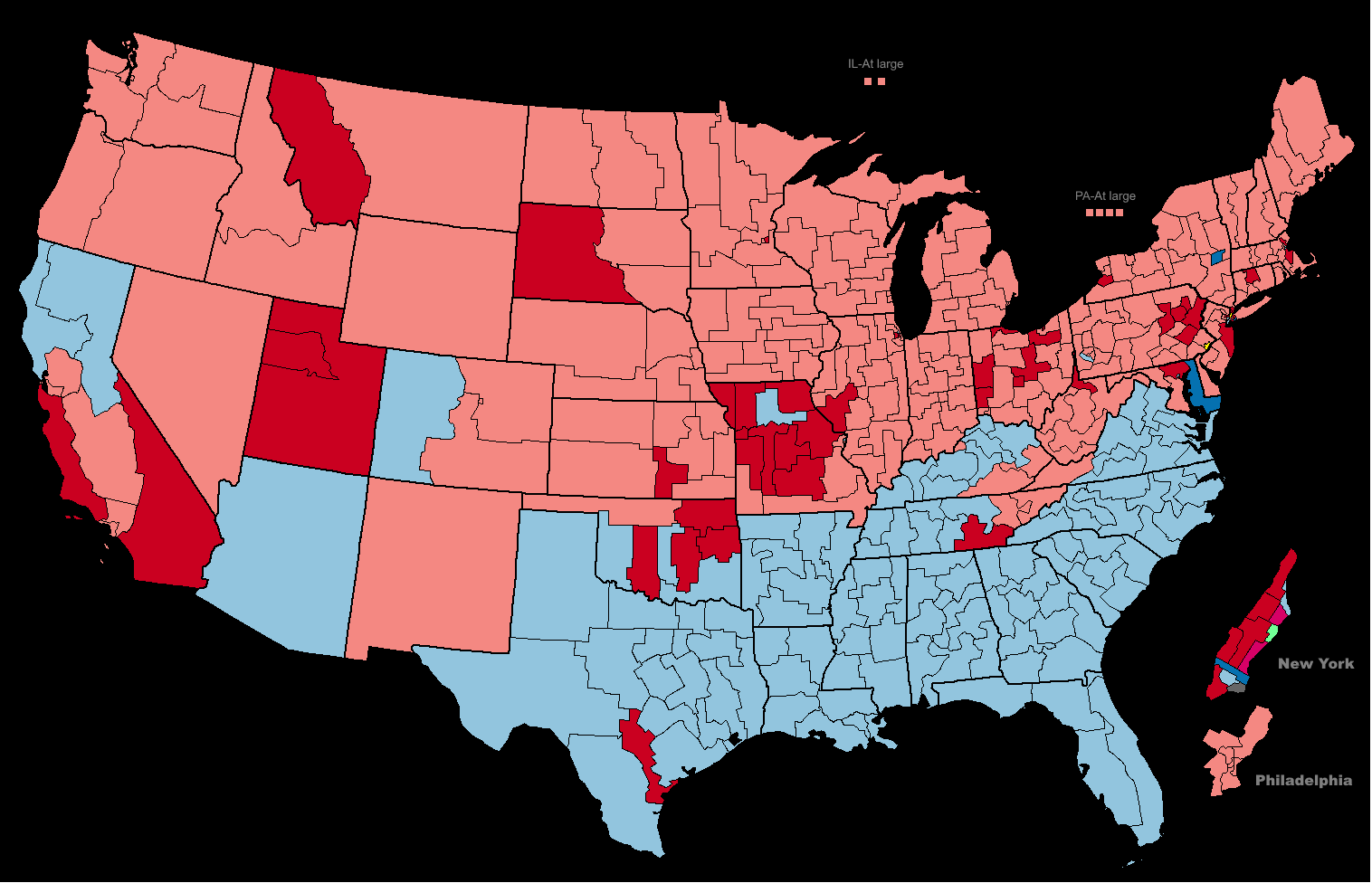

The little flags indicate which troops are present in which places.

As you can see, I am not yet decided on the exact nature of Brunswick and Hannover (merger? as monarchy or republic?), and while I'm clear on Oldenburg's becoming a Free State even under British influence, I wasn't sure with Schaumburg-Lippe and Lippe-Detmold, either. The British zone of influence is all the pink parts of former Prussia plus the other tiny little parts encircled by the British pink line. As you can see, several PRussian provinces have been split between the British and EFP powers this way: Westphalia, Saxony, and Brandenburg. Here, continuing with the provincial institutions does not look the most logical choice. Oh, and one Hohenzollern branch does get to keep a little principality in their original dynastical base for the time being, which was fairly un-proletarian and non-socialist IOTL.

I've gone for more Polish annexations than negotiated earlier in the spring, also, Danish Schleswig and Belgian Eupen-Malmedy have been marked.

The Saxony and Westphalia EFP mandate zones (as well as Berlin, on whose status I am also not 100 % set) are where the socialist council movement is strongest, and they can count on some degree of support from Bavaria (how the UoE deals with them, i.e. how much support they will lend them we shall find out).

Baden and Württemberg look entirely different. Württemberg’s King Wilhelm had been skeptical of the Great War from the start, the kingdom had enacted universal male suffrage for the second chamber of the Landstände already in the constitutional reform of 1906, and the monarch enjoyed popularity far into the liberal and social-democratic segments of the population. Once the great wave of reforms (to keep up popular support for the war) has been announced and in part started in Berlin in 1918, I see no reason whatsoever why Württemberg would not have taken a leading position again here. Female suffrage, a reform of the electoral constituencies, the inclusion of social rights in the constitution, and the reduction of the first chamber to a merely ceremonial role all seem plausible effects of the great war and the worldwide political climate of the moment to me, and they would be certainly sufficient to defang any revolutionary elements among Württemberg’s socialists. Therefore, Württemberg shall remain a (now parliamentary) monarchy. Lang läbe d’r König Wilhelm!

Württemberg becomes occupied only for a short period of time, by a very small French presence in the North and another very small Italian presence in the South. If Württemberg fully demobilizes its army, which I have no doubt that it will, then these troops are probably gone sooner rather than later – with the latest point in time probably around when the Württembergian government signs Versailles 2.0.

With regards to national politics, I expect Württemberg’s Landstände to support the Vorparlament, where one of theirs, Matthias Erzberger, is leading the Zentrum’s faction and redrawing the party’s national political agenda, while both Württembergian Zentrum, Demokratische Volkspartei [left-liberal], SPD and USPD will calculate coolly what compliance with which foreign power over matters of how Württemberg should position itself in the questions of a new German constitution and of Versailles 2.0 shall bring for the little kingdom. They will have diverging opinions on these matters, but none of this is approaching the civil war level of their Bavarian neighbors, who are going to serve as the deterring example for our solid Swabians. This also answers the question of Württemberg’s relation to the council movement: worker councils, particularly strong in Stuttgart and Heilbronn, will not be forcibly dispersed and they’re certainly able to send delegates to Elberfeld. But any major disruptive economic transformation in the kingdom is probably going to be negotiated away – which might corroborate Stuttgart’s and Heilbronn’s positions as the cities with the most well-to-do workforce within Germany (which doesn’t mean a lot in 1919, to be fair).

In Baden, a similar development could take place belatedly after the resumption of hostilities. One requirement for saving the monarchy here is removing Friedrich II. in favour of his son Max. This could occur when hostilities resume. Friedrich II. could be in favour of attempting to resist the French – and then be silently pushed to the side by both the Badenblock coalition and the Zentrum in favour of liberal and pragmatic Max. Baden is still going to be overrun by French forces, although probably only towards the very end in this scenario because Baden isn’t high up on the list of military priorities (it’s going to end up French-controlled anyway, everbody knows). Max has good OTL credentials as a reformer, and I’m sure he could have worked well together with the “Badenblock” coalition of Social Democrats and liberals and enacted reforms which go beyond those of 1904. Baden remains a grand duchy, thus. It probably needs to demilitarize completely and let the French rove freely. As for how future Badish governments could develop, I have not yet made up my mind. The council movement is active primarily in Karlsruhe; the rest of the country has been historically dominated by militant liberals, with an electorally strong Zentrum seeing itself shut out of confessionally polarized politics. The proximity to France isn’t going to weaken Baden’s militant stance against the power of the Catholic church, I suppose – although positions with regards to Versailles 2.0 etc. could change this and cause realignments. Like in Bavaria and Württemberg, overtly nationalist parties are going to be forbidden, and the French are certainly going to help in smoking out any pockets of Heimatwehr resistance.

In Saxony, the Revolution had already driven off the Wettin monarchs and installed a Free People’s State. Its USPD-led government has, in turn, been attacked by Prussian forces after the Bundesrat had declared imperial execution against Saxony. But Saxony had never been pacified. It’s seen a several month-long civil war in the spring of 1919, which in the end was decided by Luxemburg’s successful mobilization in neighboring Gotha and invading Czechoslovak forces. Even before Hindenburg’s surrender, the Revolution has triumphed in Eisenach, Erfurt, Dessau, Gera and other industrial cities in the region. In some places, workers’ councils are dominated by the USPD, in others by Luxemburg’s new IRSD (the backbone of which form the remnants of the old Spartakist left wing of the USPD, joined by new radical groups). In spite of differences, the various revolutionaries form a common Workers’ Soviet of Saxony and Thuringia and send delegates to the German Congress of Workers’ Soviets. The supreme soviet of Red Saxony is situated, once again, in Leipzig.

It does not control all Saxon and Thuringian statelets, though, and only parts of the Prussian province of Saxony in addition. At first, anti-socialist opposition is divided and overwhelmed and without a plan. But even spontaneous opposition throws wrenches into the consolidation of Red Mega-Saxony. In Gera, for example, USPD-aligned revolutionaries have forced Heinrich XXVII. to abdicate as prince of both Reuß jüngere Linie and Reuß ältere Linie, and declared that all state functions are temporarily taken over by the councils (aligned to Leipzig) until a constituent assembly is elected. But while they soon manage to keep things running smoothly again in Gera, a centre of textile industry and a beating heart of the labour movement, they have little power projection into even the rural Southern reaches of the two principalities – and in reaction, on June 3rd, the old Landtag in Greiz declared that public administration in the former principality of Reuß ältere Linie would be overseen by them, not by any workers’ council, and they decided to throw in their lot with the Frankfurt Vorparlament to prepare the ground for elections to a constituent assembly, delegating one from among their rank to represent their little statelet in Frankfurt. Similar developments took place in the Duchy of Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, where Gotha is a revolutionary stronghold of Luxemburg’s IRSD, but Duke Carl Eduard was able to flee unobstructedly to Coburg. Likewise, in the Grand Duchy of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, Eisenach and Apolda fell into the hands of the revolutionaries, but in quiet Weimar, Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst still sits unobstructedly and even takes the initiative into his own hands by calling new elections for the grand duchy’s Landtag and seeking contact with the British military administration farther to the North in order to avoid being dethroned and seeing his entire grand duchy slide into radical socialism. Other principalities (both Schwarzburgs, the Duchies of Sachsen-Meiningen and of Sachsen-Altenburg) are also relatively unaffected by the red wave at first – on the other hand, Erfurt, which is legally in Prussia, is completely controlled by socialist revolutionaries.

The British don’t come to the aid of threatened monarchs so far South, though – the Saxon and Thuringian principalities are within the Czechoslovak occupation zone. But Czechoslovak military presence is sparse; they do not have the numbers to occupy a large territory. Nor are they interested in staying indefinitely – Masaryk’s government is desperately short of funds (like most other governments, too). Czechoslovakia’s strategic aims had been a) to remove the threat of a powerful Germany which might reclaim the Sudetenland from them, and b) to appear as a strong and reliable ally and important power in the concert of the EFP. Both of these have been achieved with their “joyful ride” towards Berlin and their formulation of a common new draft with the UoE for a peace treaty with many small Germanies (while the British and Americans still hold on to the idea of one German government which could shoulder this responsibility, which they hope to resuscitate through the Constituent Assembly to be elected). This draft envisions Greater Saxony and Thuringia as an “EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development” – which combines multi-national oversight, including a smaller Czechoslovak contingent, with explicit openness towards the possibilities of socialist experiments, but also towards a semi-sovereign statelet of their own for the Slavic-speaking Lusatian Sorbs of formerly Royal Saxony and Prussia’s adjacent provinces. (Sorbian rights come in a distant third place on Masaryk’s list of priorities, but still. Remember that while Masaryk is a bourgeois liberal nationalist, the Czechoslovak government overall has no anti-socialist leanings whatsover – they are one of the UoE’s closest allies, and there are moderate socialist parties in the coalition which governs the young country.)

After a few weeks, the Czechoslovaks, and more importantly: their UoE allies, observe with great concern that the non-Leipzig-aligned pockets are serving as bases into which remnants of nationalist Heimatwehren retreat and where they form anew, their ranks swelling with people opposed to Luxemburg’s radical socialist vision. Decisions are taken therefore to orchestrate a “revolutionary wave”, aided by the two EFP powers present in the region, to wash over the last remnants of the old order. In the end, the old tiered parliaments are dissolved everywhere and the Grand Duke of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, the Duke of Sachsen-Meiningen, the Duke of Anhalt, the Duke of Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, the Duke of Sachsen-Altenburg, and the Princes of the two Schwarzburgs and Reuß’ are all removed, and not only their domains and castles, but also those of most other nobles are plundered by revolutionary hordes, partitioned or opened for the public to hunt and poach in, and placed under the military jurisdiction of what, in late July, becomes the Governing Council of the EFP Mandate over Saxony and Thuringia. Saxony and Thuringia have become red strongholds.

Prussia’s old parliament is dissolved. In the place of its resigned government, an Allied Council for the Administration of Prussia is installed. Its provinces begin to unravel: a Rheinische Republik is established with a new constitution (no military, full sovereignty). The Saxon province, as mentioned, is partly controlled by Red Saxony and merged into an EFP Mandate. Another major centre of socialist revolution in former Prussia is the Ruhr region – here, by early June, most cities have come under the soviet control, and here is the beating heart of Germany’s socialist revolution, embodied in the Elberfeld Congress. The Red Ruhr is no monolith, either, though: it has International Communists, USPD, and the anarcho-syndicalist FAU, who can actually mobilise the largest number of militant supporters. In the Kerensky-Benes draft for Versailles 2.0, the Ruhr Industrial Region is marked as an EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development, too – which means that the council socialists can manage internal affairs for the time being as they see fit, as long as they do not put up any resistance to the military occupation by the French and Belgians.

The same EFP structure is proposed for Hesse, too, from Prussian Bad Karlshafen in the North to Grand Ducal Worms in the South. Here, there is no hegemony of socialist groups – instead, there are ongoing small-scale clashes between a broader revolutionary coalition (left-liberals and various socialists), supported by France, and remnants of the Heimatwehren (the French had been so busy to hurry towards Berlin, too, that they had not been very thorough in capturing, disarming and detaining von Wetter’s army, so some remnants are still left, joined by new voluntaries who oppose the radical change which is gripping Hesse’s Western and Eastern neighbors). Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig is still in Darmstadt, but actual power is exerted mostly by the French. French military occupation in Hesse is playing a duplicitious game: they are hosting and offering safety and protection to the Vorparlament in Frankfurt, while also supporting militant groups who would much rather have the transitional process being overseen by workers’ councils, and while exerting pressure on the Rhenish Republic to take as distanced a stance towards any vision of re-unified Germany as possible and obstruct all processes by which a concentration of the powers now in the hands of the various fission products of the empire could occur. If Versailles 2.0 becomes reality, there will probably be elections for a unified Hessian Landtag (for the Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau together with the former grand duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt), and if this happens, I don’t see it adopting anything other than a republican constitution. Heimatwehr resistance in Hesse is not something which couldn’t be eradicated, or at least reduced to dispersed terrorist cells, in a couple of months.

The security situation is entirely different in the East – i.e. in Pommerania, Silesia, and West and East Prussia. Here, large numbers of armed anti-Russian, anti-Polish, anti-socialist, anti-republican, anti-democratic, ultra-nationalist groups are still roaming. The Vinetabund is just one embodiment of this trend. This is a problem the UoE must deal with with only Polish “help” – and the Poles are only ever really helpful where they are granted full incorporation of a region into their emerging republic. This is going to be one motive why a revised Kerensky-Benes draft for Versailles 2.0 is going to award yet more German territory to Poland than the map I’ve shown you which depicted the negotiations in February/March. We’re talking about all of West Prussia, most of Upper Silesia, and yet more of Pommerania and East Prussia. Only this leaves the UoE with a challenge it can tackle with the limited forces that are politically feasible to maintain in East Germany. Like Danzig, the remaining territories designated not to become Polish are proposed to be fused into one EFP Mandate Zone for Free Democratic Development. Only here, the UoE has very little grassroots structures to build their regime change on. That does not mean they can’t create them – but that would take quite a bit of political genius. To the Russian political eye, “Germany” is an advanced industrialised nation, different from their rural self. It takes a bit to realize that East Elbia is socially and economically not too dissimilar to the former Russian Empire: a landed and military aristocracy ruling over an impoverished peasantry from their manors, producing cash crops with the cheapest available workforce. Once they realize this, the answer is easy: mobilise the dependent peasantry and sharecropping proletariat by enacting a land reform, a process in which peasant councils are formed which can serve as the backbone of a new socialist democracy closely aligned to the UoE. (The towns are more difficult, I admit – but the towns were and would be leaning Social Democratic IOTL, so the big question would be whether such a policy could somehow dissect the SPD from the idea of German unity and sovereignty to which it is quite closely wed. But I haven’t decided whether this course of action is going to take place at all – it would not be bloodless, to be sure, but all alternatives would be the UoE’s early Vietnam. It is vital for them to understand that they must drive a wedge between the German Junkers and their German underlings in East Elba. If they weld them together instead, they’re fried. Handing over territory to the Poles is one recipe for welding the two together in nationalist fervor. The problem is, it’s such a temptingly easy way out. What do you think the UoE will do in East Elbia?

And that’s not all the carving that’s being done to Prussia. Sorbian Lusatia has already been mentioned – most of it lies in Prussia, so if it gets singled out for “national self-determination”, that’s yet more amputations.

Oh, and Berlin. Berlin must be controlled by all Entente powers together, even if their Entente is not too cordial anymore. It’s probably moving towards a status as a free city.

Which leaves those parts of Brandenburg, Hannover, Schleswig-Holstein and Westphalia which are occupied (or earmarked for occupation) by Anglo-American forces. I have finally made up my mind about the US, and I will disclose this and how it affects British policy in the next update, too. Long story short, though: the British will see the writing on the wall and make sure they have some client states in Germany, too. Would they weld Schleswig-Holstein, Hannover, Westphalia, and “their” parts of Brandenburg and Northern Saxony together into a new “rump Western Former Prussia” or perhaps a “Northern German Republic”? I’m not sure – they could just let each province transform into an independent republic. What I’m pretty sure about is that Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck maintain their status as free cities, and that quiet Mecklenburg (both grand duchies unified, Friedrich Franz IV. was administering Strelitz, too, anyway after Adolf Friedrich’s suicide) remains a Grand Duchy, albeit probably with a more parliamentary constitution. Friedrich Franz was neither anti-parliamentary, nor was he particularly happy with the expansionist war plans. Oldenburg, on the other hand, is ripe for republicanisation or absorption into Hannover, even under British control, given its Grand Duke Friedrich August’s militarist stance and his own unpopularity.

Given that even in the British zone of influence, there is a real gore of weird boundaries and tiny statelets like Waldeck-Pyrmont, Lippe, Schaumburg etc., the most logical solution would be some degree of territorial consolidation / clean-up, but I’m not sure how this could be done without dethroning all monarchs, and even then it took the Nazis and another World War to remove these relics of the Medieval HRE from Germany’s map. The alternative is at least a zone of free commerce and travel (a new Zollverein) – ideally, this would be something legislated by a Constituent Assembly…. If not, its absence would be a pestering sore and things would not work out at all for the tiny states as independent entitites.

The little flags indicate which troops are present in which places.

As you can see, I am not yet decided on the exact nature of Brunswick and Hannover (merger? as monarchy or republic?), and while I'm clear on Oldenburg's becoming a Free State even under British influence, I wasn't sure with Schaumburg-Lippe and Lippe-Detmold, either. The British zone of influence is all the pink parts of former Prussia plus the other tiny little parts encircled by the British pink line. As you can see, several PRussian provinces have been split between the British and EFP powers this way: Westphalia, Saxony, and Brandenburg. Here, continuing with the provincial institutions does not look the most logical choice. Oh, and one Hohenzollern branch does get to keep a little principality in their original dynastical base for the time being, which was fairly un-proletarian and non-socialist IOTL.

I've gone for more Polish annexations than negotiated earlier in the spring, also, Danish Schleswig and Belgian Eupen-Malmedy have been marked.

The Saxony and Westphalia EFP mandate zones (as well as Berlin, on whose status I am also not 100 % set) are where the socialist council movement is strongest, and they can count on some degree of support from Bavaria (how the UoE deals with them, i.e. how much support they will lend them we shall find out).