The Finnish Civil War, part two (June 1918)

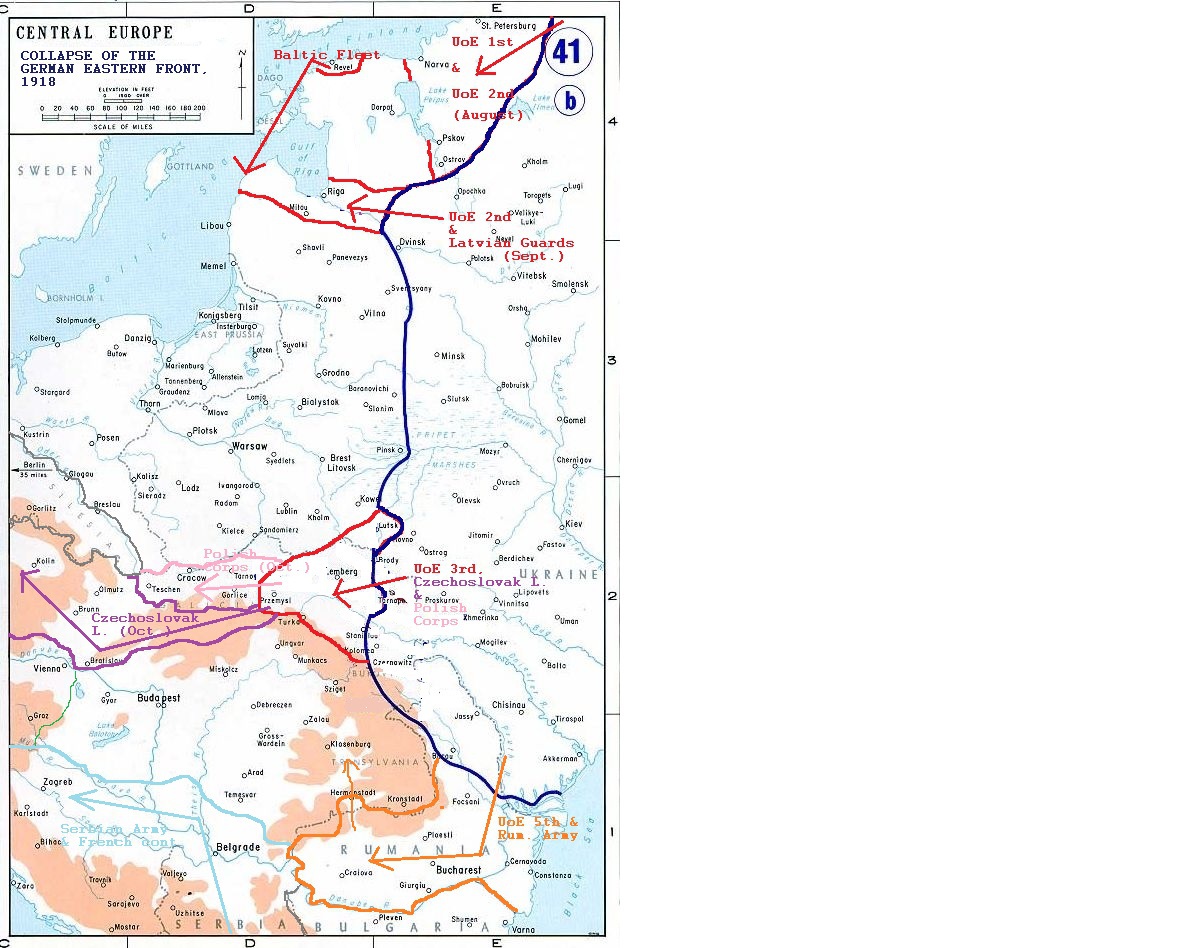

Trotsky decided not to get bogged down in a protracted civil war, but to instead foster the spreading of the Revolution with the help of sailors and thousands of additional raiding and landing troops on board their impressive vessels. He launched a series of naval attacks which would restore the Gulf of Finland to the control of the Union of Equals’ Baltic Fleet, which would have massive repercussions in Finland, as stated in the last update.

The departure of so many soldiers and experienced revolutionaries, along with a lot of military equipment, tilted the balance between the three warring factions in Finland. It left the Red revolutionaries in the South vulnerable, but while some of them seemed acutely aware of this existential threat, other revolutionary socialists in Helsinki, Tampere, Kotka, or Wyborg rejoiced. Especially to those socialists with syndicalist or anarchist leanings, the end of the military regime meant the great chance for all the workers - Finns, Russians, Swedes and everyone else united - to truly take their fate into their own hands, to decide on their factories’ inter-relations without everything being geared by a military commissar with an iron fist towards sustaining the civil war effort. Now was the time for the real socialist utopia to materialize itself in Finland!

The enthusiasm of this group, whose leaders were the brothers Eino and Jukka Rahja, August Wesley and Yrjö Sirola, did not last long. Their more cautious comrades saw the writing on the wall when a division of the Vaasa Senate swept away contingent after contingent of poorly organized militia of volunteers before them on their march on Tampere. Recruitment in the countryside went from bad to worse, with entire villages across the South now successfully resisting both the draft and requisitioning attempts while declaring themselves “restored” to the legitimate rule of the Kuopio Senate. On June 13th, Kullervo Manner, heading a delegation of realistically inclined factory deputies, met with Oskari Tokoi in Mikkeli, to discuss terms under which the South could accept the full restoration of the authority of the Kuopio Senate and its Eduskunta.

Tokoi had previously made another attempt at reconciliation with the Vaasa Senate. Negotiations failed, however, when Svinhufvud insisted on independence from Russia, an alliance with Germany, and the Red rebels in the South feeling the full might of the sword of legal order as preconditions for the disarming of his troops. Given the radicalization of the previous weeks and months, it is questionable if the conflict could have been ended immediately even if Tokoi had given in. Indeed, just as rebels supporting the Kuopio Senate had emerged among the landless throughout rural Finland, militant anti-socialists, mostly of formerly landowning background, formed their own clandestine networks aimed both against Tokoi and the Reds in the South. The most extreme of them, the “Brothers of Hate”, or “Vihan Veljet”, began its insurgence on the very day of the fruitless negotiations between Tokoi and Svinhufvud. They became well known for burning down huts, massacring Tokoi-loyalist peasant leaders, and targeting local Järjestyskunta officers in often suicidal terrorist attacks. [1]

Turned down by Svinhufvud, Tokoi saw the meeting with Manner as the last chance to reunify his conflict-stricken country, with his situational disposition towards compromise and leniency proving vital to the formulation of the compromise which resulted from this meeting. The Manner-Tokoi Pact committed to the reversion of extralegal expropriations and the upholding of property rights, especially in the industrial sector, but it also acknowledged the newly formed factory workers’ councils and their local networks of cooperation, granting them a new role as bodies of arbitration for disputes between employers and individual employees and allowing them to participate in the planning and oversight of welfare and relief measures. They would work alongside representatives from local church parishes, professional organizations, and the chambers into which manufacturers were organised. It placed the organization of conscription in the hands of the regular elected local bodies of communal government, emphasizing an equality of draftees from urban and rural backgrounds, and while it promised amnesty to anyone who surrendered to the legitimate government before June 30th and who had no committed “atrocities” in the name of ideology, it also clarified that any decrees issued by the soviets which were in contravention of existing laws were null and void.

The Pact did not go down without opposition in the industrial centres of the South. Uncompromising radicals like the Rahja brothers and others with connections to Russian ultra-left opposition groups like the rump Bolsheviks (notably among them Ali Aaltonen, Adolf Taimi, and Alexander Schrottman) continued to organize those among the socialist workers who would not lay down their arms and renounce what they had gained for themselves, not even in the face of the threat of the Vaasa troops, who conquered Tampere on June 19th after over a week of bitter fights, in which the courage and bravery of proletarian militia proved no match against the superior weaponry and organization of the Vaasa army and its Jääkäri backbone.

But as news of atrocious retributions even against unarmed workers committed by Suojeluskunta in Tampere spread across the South, socialist resistance against the Manner-Tokoi Pact began to falter, and factory after factory, town after town switched sides, closing the ranks against the Vaasa Army, which in its turn had prevailed in Pori, Rauma, and Turku.

In the last week of June, the new front line ran from Oulu in the North to Tammisaari in the South, dividing a Vaasa-controlled West Coast from the rest of the Finland, in which Oskari Tokoi’s Senate struggled, with increasing success, to restore its legitimate power.

While there were still initiatives for renewed negotiations aimed at a national reconciliation, the Vaasa and the Kuopio Senate both prepared for the last round in this bloody struggle. The Kuopio Senate controlled over three quarters of Finland’s population and territory and comparatively high popularity, but the forces of the Vaasa Senate were both better-trained and had received superior equipment from the Germans, while the Kuopio Senate merely received a trickle of weaponry from Murmansk, carried across the green border by an eager Russian Commission, who had rejoiced at the conclusion of the Tokoi-Manner Pact and attempted to support their fellow leftist reformers in Finland as best they could – but even combined with the output of hasty production undertaken all over the South, that was not enough by far to provide sufficient supplies to the increasingly large military force which the Kuopio Senate had managed to raise.

June 29th, 1918 was a comparatively quiet Sunday. The country seemed to hold its breath. Tokoi and his fellow Senators had decided to make a tour to Helsinki and show themselves to their citizens in a public ceremony, both to make a show of normalcy and keep up civil courage, and to garner support for the compromise and the new order which had been negotiated in the Tokoi-Manner Pact. Thousands had gathered in the sun-bathed Kaisaniemi Park, many waving the banners of various political groups which had formed over the past months, shouting this or that demand, attending the ceremony to support or protest against the Senate, to cry out their demands, but many more simply to watch. They would all become witnesses of the suicide attack by a Vihan Veljet group which targeted the assembled Senators, and managed to kill Oskari Tokoi, Kyösti Kallio and three bodyguards, wounding four more and further Senators Väinö Tanner and Karl Wiik.

[1] And quite certainly also, as @Karelian has pointed out, engaging in the violent settlement of local grudges in a context of general lawlessness and unrest.

Trotsky decided not to get bogged down in a protracted civil war, but to instead foster the spreading of the Revolution with the help of sailors and thousands of additional raiding and landing troops on board their impressive vessels. He launched a series of naval attacks which would restore the Gulf of Finland to the control of the Union of Equals’ Baltic Fleet, which would have massive repercussions in Finland, as stated in the last update.

The departure of so many soldiers and experienced revolutionaries, along with a lot of military equipment, tilted the balance between the three warring factions in Finland. It left the Red revolutionaries in the South vulnerable, but while some of them seemed acutely aware of this existential threat, other revolutionary socialists in Helsinki, Tampere, Kotka, or Wyborg rejoiced. Especially to those socialists with syndicalist or anarchist leanings, the end of the military regime meant the great chance for all the workers - Finns, Russians, Swedes and everyone else united - to truly take their fate into their own hands, to decide on their factories’ inter-relations without everything being geared by a military commissar with an iron fist towards sustaining the civil war effort. Now was the time for the real socialist utopia to materialize itself in Finland!

The enthusiasm of this group, whose leaders were the brothers Eino and Jukka Rahja, August Wesley and Yrjö Sirola, did not last long. Their more cautious comrades saw the writing on the wall when a division of the Vaasa Senate swept away contingent after contingent of poorly organized militia of volunteers before them on their march on Tampere. Recruitment in the countryside went from bad to worse, with entire villages across the South now successfully resisting both the draft and requisitioning attempts while declaring themselves “restored” to the legitimate rule of the Kuopio Senate. On June 13th, Kullervo Manner, heading a delegation of realistically inclined factory deputies, met with Oskari Tokoi in Mikkeli, to discuss terms under which the South could accept the full restoration of the authority of the Kuopio Senate and its Eduskunta.

Tokoi had previously made another attempt at reconciliation with the Vaasa Senate. Negotiations failed, however, when Svinhufvud insisted on independence from Russia, an alliance with Germany, and the Red rebels in the South feeling the full might of the sword of legal order as preconditions for the disarming of his troops. Given the radicalization of the previous weeks and months, it is questionable if the conflict could have been ended immediately even if Tokoi had given in. Indeed, just as rebels supporting the Kuopio Senate had emerged among the landless throughout rural Finland, militant anti-socialists, mostly of formerly landowning background, formed their own clandestine networks aimed both against Tokoi and the Reds in the South. The most extreme of them, the “Brothers of Hate”, or “Vihan Veljet”, began its insurgence on the very day of the fruitless negotiations between Tokoi and Svinhufvud. They became well known for burning down huts, massacring Tokoi-loyalist peasant leaders, and targeting local Järjestyskunta officers in often suicidal terrorist attacks. [1]

Turned down by Svinhufvud, Tokoi saw the meeting with Manner as the last chance to reunify his conflict-stricken country, with his situational disposition towards compromise and leniency proving vital to the formulation of the compromise which resulted from this meeting. The Manner-Tokoi Pact committed to the reversion of extralegal expropriations and the upholding of property rights, especially in the industrial sector, but it also acknowledged the newly formed factory workers’ councils and their local networks of cooperation, granting them a new role as bodies of arbitration for disputes between employers and individual employees and allowing them to participate in the planning and oversight of welfare and relief measures. They would work alongside representatives from local church parishes, professional organizations, and the chambers into which manufacturers were organised. It placed the organization of conscription in the hands of the regular elected local bodies of communal government, emphasizing an equality of draftees from urban and rural backgrounds, and while it promised amnesty to anyone who surrendered to the legitimate government before June 30th and who had no committed “atrocities” in the name of ideology, it also clarified that any decrees issued by the soviets which were in contravention of existing laws were null and void.

The Pact did not go down without opposition in the industrial centres of the South. Uncompromising radicals like the Rahja brothers and others with connections to Russian ultra-left opposition groups like the rump Bolsheviks (notably among them Ali Aaltonen, Adolf Taimi, and Alexander Schrottman) continued to organize those among the socialist workers who would not lay down their arms and renounce what they had gained for themselves, not even in the face of the threat of the Vaasa troops, who conquered Tampere on June 19th after over a week of bitter fights, in which the courage and bravery of proletarian militia proved no match against the superior weaponry and organization of the Vaasa army and its Jääkäri backbone.

But as news of atrocious retributions even against unarmed workers committed by Suojeluskunta in Tampere spread across the South, socialist resistance against the Manner-Tokoi Pact began to falter, and factory after factory, town after town switched sides, closing the ranks against the Vaasa Army, which in its turn had prevailed in Pori, Rauma, and Turku.

In the last week of June, the new front line ran from Oulu in the North to Tammisaari in the South, dividing a Vaasa-controlled West Coast from the rest of the Finland, in which Oskari Tokoi’s Senate struggled, with increasing success, to restore its legitimate power.

While there were still initiatives for renewed negotiations aimed at a national reconciliation, the Vaasa and the Kuopio Senate both prepared for the last round in this bloody struggle. The Kuopio Senate controlled over three quarters of Finland’s population and territory and comparatively high popularity, but the forces of the Vaasa Senate were both better-trained and had received superior equipment from the Germans, while the Kuopio Senate merely received a trickle of weaponry from Murmansk, carried across the green border by an eager Russian Commission, who had rejoiced at the conclusion of the Tokoi-Manner Pact and attempted to support their fellow leftist reformers in Finland as best they could – but even combined with the output of hasty production undertaken all over the South, that was not enough by far to provide sufficient supplies to the increasingly large military force which the Kuopio Senate had managed to raise.

June 29th, 1918 was a comparatively quiet Sunday. The country seemed to hold its breath. Tokoi and his fellow Senators had decided to make a tour to Helsinki and show themselves to their citizens in a public ceremony, both to make a show of normalcy and keep up civil courage, and to garner support for the compromise and the new order which had been negotiated in the Tokoi-Manner Pact. Thousands had gathered in the sun-bathed Kaisaniemi Park, many waving the banners of various political groups which had formed over the past months, shouting this or that demand, attending the ceremony to support or protest against the Senate, to cry out their demands, but many more simply to watch. They would all become witnesses of the suicide attack by a Vihan Veljet group which targeted the assembled Senators, and managed to kill Oskari Tokoi, Kyösti Kallio and three bodyguards, wounding four more and further Senators Väinö Tanner and Karl Wiik.

[1] And quite certainly also, as @Karelian has pointed out, engaging in the violent settlement of local grudges in a context of general lawlessness and unrest.