Elections to the Duma of the Russian Federative Republic (December 1918)

As you will have already noted in the coverage of the elections of the other federative republics and of the Union Presidency, the UoE general elections of December 1918 are characterized by a very heavy overweight / hegemony of the Leftist side of the political spectrum. Now, “Left” and “Right” are not anthropological constants, of course, they are historical, and just as they emerged, they can also dissipate. The old Marxist (and Narodnik, too!) utopia of a classless society which has overcome its antagonisms is one such hypothetical state. Is this really what is happening here? Only time will tell. History has shown us countless examples of revolutions in which the Left dominated very much, bringing forth political landscapes which started out occupying only what is Left of Centre, but in the following years and decades, some parties shifted rightwards so that more of the spectrum typical for modern developed societies is occupied. (Portugal comes to mind: ever since the Carnation Revolution, the country’s political scene is divided between Social Democrats, Socialists and Communists. Only, the “Social Democrats” are by now economically neoliberal and socially conservative, thus by all means a conservative party, the Socialists are moderate, slightly left-of-centre Social Democrats, and the Communists have travelled the route over Eurocommunism to becoming the sort of separated left wing of social democracy which parties like the German Linke, the Dutch Socialists, the Spanish Unidos Podemos etc. also occupy.) So, is this what happens here? Will one of the parties shift to the right and restore the balance we are so familiar with? (If so, then it appears that the SRs are predestined for this course, given how they’re already perceived as the “moderates” with Avksentiev as their President-Elect, and the less class-antagonistic, more harmony-oriented ideological outlook of Narodnichestvo would facilitate this, too.) On the other hand, the balance we are familiar with is very much a child of the short 20th century, which ITTL is only just beginning. Before the Great War, with limited suffrage in many countries, the old bourgeois alternative between Liberals and Conservatives had been more prominent (while certainly already decaying), and the trends of our current century may point in other directions, too, what with the disintegration of the 20th century Left.

Only the continuation of this TL will tell if 1918 is going to be an exception or the new norm. I am very interested in your opinion on this matter, dear readers, of course!

But for the moment, it must be stated that this is clearly a trend from OTL which I could not have ignored if I had wanted to (which I didn’t *grin*). It would be wrong to say that Russia follows this trend – it is much more adequate to say that Russia has created this 1917-1918 trend. The federative republics we have covered so far have their own local histories, but in the large tilt to the Left, they are following something which has begun in many places, but certainly erupted first in Petrograd and took a number of escalating steps there.

Many others have written much more adequately about this trend than I could ever hope to. I will limit myself to pointing out where the divergences of TTL have picked up on OTL developments and where they deviated from them. By the time of the PoD, the massive dynamics had already been in full motion: the utter collapse of a delegitimized tsarism (and with it the entire discourse on “constitutional monarchy” vs “republicanism” etc.), the self-empowerment of the masses (embodied in the soviets), the exhaustion with regards to the war, the economic collapse (which was also a collapse of various economic policies which had dominated pre-war politics: market- and capital investment-oriented development of industry and large scale agriculture on the one hand side, militarized state dirigism on the other. If you’re looking at trends observable in the local duma elections of the summer of 1917 IOTL, and then in the Constituent Assembly elections of December 1917 OTL, the continuous leftward dynamics can’t be overseen, and the same goes for the implosion of the Russian Right. By the times of the CA election, the Kadets are the most right-wing option which is still at least barely visible – before the Great War, any ordinary educated Russian would clearly have placed the Kadets on the Centre-Left of Russia’s political landscape…

ITTL, the process is accelerated and channeled at once when Prince Lvov’s coalition (of Kadets, Octobrists, independents and one Trudovik: Kerensky) bluffs, their bluff is called, and the soviets take over power temporarily and with a good degree of political legitimacy, without a single shot being fired, and they call CA elections. The CA elections of TTL’s June 1917 thus already mirror OTL’s December 1917 outcome – with the exception of the absence of Menshevik and Right SR delegitimisation through support of a bourgeois-acting Provisional Government, an October Revolution and thus of Bolshevik hegemony over the country and over the RSDLP. Like IOTL, the SRs have inevitably been the largest party, and so they, who never led a government IOTL, have done so ITTL since July 1917. They deliver on their main promise – land reform – which secures their rural powerbase. Although attacks from the Left are no less fierce than IOTL, the SRs are in a solid-enough position to embrace those of their critics who are willing to be embraced in the November Realignment – and ruthlessly persecute the rest, both on the Right, which has discredited itself another time in August 1917 with its ties to the botched Kornilov Coup, and on the Left (remaining Bolsheviks and anarchists). Over the course of 1918, this very broad socialist coalition was faced with more military defeats, economic crisis, the need to relocate to Moscow, and ultimately the reversal of the war, having been able to triumph at the end, which still leaves the situation of the population quite as destitute as before, only now they no longer have to fear to get sent into trenches to die there. Divisions between SRs and SDs became more and more nuanced throughout 1918, and so the two parties face each other as the electoral giants of the new Republic – both on the Union level and on the Russian level. Given the conditions they had to work in, they were relatively successful together. This is not the only, and maybe not even the primary reason why they’re dominating the elections: the fact that the extreme Right is now tainted once again with its collaboration with Markov and the latter’s downfall, the fact that the Kadets are at a loss for how to adapt to the new situation, and not least the fact that the government, through the instrument of the VChK, has been oppressing and imprisoning any groups who are seen as “saboteurs” who want to overthrow the new system. (As has been noted, this is a specifically Russian situation, since the republics who had already enjoyed autonomy at the time of the November Realignment clearly objected to the VChK poking their noses into their republic’s affairs.)

Actually, this is probably the moment where I should describe how the Russian Federative Republic came into being and what its constitutional structures are. The Russian FR is an exceptional case indeed – it is the only federative republic whose constitution was not drafted by a national council or assembly of some sort or other, and whose “integration” into the Union of Equals did not require a Concordance, state contract or anything else of this sort. In some sense, this is logical, because the Russian Federative Republic, unlike all others, was not created by an autochtonous group seeking national self-determination. It was created after everyone else (well, before the Bessarabians and the Belorussians, but still) had got their own federative republic. It was created out of a desire for constitutional systematicity – the Union of Equals was to be composed of federative republics, and so “rest Russia” had to form one, too. (This is not to say that there had never been Russian nationalism. There certainly has been, but its objective had been different. In many cases, it had been directly opposed to what happened in 1917 and 1918 which ultimately led to the establishment of a Russian FR.)

The constitution of the Russian FR was drafted by the very same Constitutional Assembly in Petrograd (and later Moscow) which also drafted the constitution of the Union – only when the Russian constitution was discussed and voted on, the representatives of the already-autonomised republics were required to leave the plenary. (The Russian FR’s constitution has therefore been voted on by Northern Caucasian, Belorussian and Bessarabian delegates, too, because their federative republics were formed only later.) It stipulated that the Russian FR was to be a parliamentary socialist republic, where the Duma would vote on penal and civil laws, general taxes, education, infrastructure and the like, whilst local, regional and republic-wide soviets would set the rules of the economic game, provide social security and healthcare, administer common resources etc. The soviets would appoint a number of permanent committees to oversee day-to-day economic manamgement, whereas the Duma would elect a Prime Minister, who would appoint ministers to run the respective segments of the republican administration. When it was established in November 1917, it was determined that the elections to the next Duma (delegates to the soviets could be elected and recalled at will, without guaranteed terms, by those who delegated them) would be held on the same day on which Union-wide Presidential elections would also be held. In the meantime, Russian-only affairs would be handled by a sub-committee of the People’s Commission (popularly referred to as Roskom). Roskom, which over the course of 1918 had not been exactly very important since most decisions were still taken by the Commission at large, was officially chaired by a Bread Menshevik, Alexander Martynov (i.e. someone from the smallest and weakest group in the November Realignment coalition).

The effect of this late and involuntary “birth of a national republic” caused a lot of lack of popular knowledge in Russia about the exact differences between the Duma and the old Constituent Assembly, between the Russian Prime Minister and the President of the Union etc. This way, the Presidential election system, whose effect is that of a concentration on a handful, often only two, main contenders, heavily influenced electoral behavior in the Russian Duma elections, too, especially since people voted for both on the same day in the same voting booth.

The Russian Duma is elected in a mixed system of personalized proportional representation (like (West) Germany’s system after 1949) – but since the vast majority of Russian voters are not yet extremely familiar with the minutiae of the differences between Union Presidency, Federative Republican Duma and all that, there is a very strong tendency to vote for the Duma list of the same Party whose candidate they also voted for President. This, again, strengthens the IRSDLP(u) and the SRs at the detriment of smaller parties.

The abysmal performance of the Kadets and Trudoviks (there is nothing of any substance left standing to the Right of the Kadets at the moment) as well as of Bukharin’s remaining rump Bolsheviks (who renamed themselves into International Communist Party) and Julius Martov’s rump Mensheviks (who simply called themselves Russian Social Democratic Labour Party now that the name had been abandoned both by the ICP and the IRSDLP(u)) has other reasons, too:

The Kadets are still struggling to find their position in the new system. They oppose most of the socio-economic and political transformations which happened after Lvov’s demission, but for obvious reasons they also don’t rally for a counter-revolution. They did not want the new constitution and they objected heavily (but without any success) to the referendum held on it, but now they have no choice but to play by the new rules. They had not openly supported Kornilov’s coup, but also not credibly distanced themselves from it. They had not collaborated with Markov’s puppet regime, but the resistance against it had been formed and led by others. They had always supported the war effort, but now the radical Left, who had been full of defeatists, was basking in the glory of victory. Their economic policy agenda utterly unrealistic to be implemented under the soviet system, but the Kadets also knew they couldn’t take on the soviets single-handedly (no matter how strong they would become in the Duma – well, they would not become strong…). Their social powerbase had, in part, turned to the parties of the Left, or was turning away from politics, and to some degree was even emigrating, seeking better opportunities to pursue their happiness in North or South America. Pavel Milyukov’s days at the helm of the party were numbered, everyone knew that. Leading his party into defeat in the Duma elections would be his last “accomplishment” – even before the official results were announced, he resigned from his position.

The Popular Socialist Labour Party (or short: Trudoviks) was suffering from their lack of structures in the territory. In tsarist times, they had been the outermost leftist representatives tolerated in the toothless Duma, also serving as a mouthpiece for other, suppressed groups – their moment of glory had been the soviet interregnum in May 1917 when Alexander Kerensky had led the People’s Commission together with Victor Chernov and Fyodor Dan. But there had been little time to prepare for the elections to the Constituent Assembly in 1917, and the Trudoviks, who appeared soft now, had not been able to put a foot on the ground either in the countryside, where peasant councils formed, utterly dominated by the SRs, or in the industrialised cities, where workers councils were shifting ever leftwards within the framework of Russia’s Social Democracy. The November Realignment left them in the opposition, where they shared many of the problems described with regards to the Kadets above. There was one important difference, though: the Trudoviks would be represented in the new Union government, and they would stand at the SRs’ side in a new Duma coalition. The Trudoviks were not yet just a Kerensky election club – politicians like Alexander Zarudny had too much of a profile for that to happen. But they were a small faction.

Between the Kadets, Trudoviks, SRs and IRSLDP(u), there was really no political space left for the last Mensheviks who have not joined the IRSLDP(u). In the December 1918 elections, they were ultimately reduced to the status of a splinter party. After this humiliating failure, its more profiled and ambitious personnel would soon join leave and the party would ultimately dissolve – Irakli Tsereteli, for example, would remain affiliated with the Georgian (Menshevik) Social Democrats (who had founded the Federation of Independent Social Democrats) and represent Georgia in the Council of the Union (more on this institution in a later update); Alexander Potresov, Fyodor and Lydia Dan and many others joined the Trudoviks, while Julius Martov, for whom the Trudoviks were decidedly too un-internationalistic and theoretically under-sophisticated, would become one of the “independent” political thinkers of the next decade (and obtain a professorship at the Lomonosov).

Bukharin’s International Communists (=former Bolsheviks), on the other hand, had suffered from serious obstruction throughout the duration of the war. When the war ended, the situation became a little more relaxed and the ICP was not hindered to participate in the Duma elections – but it had been marginalized too long, suffered too many losses (to the IRSDLP(u) as well as to imprisonment) and been infiltrated too heavily by undercover VChK agents. Its showing at the booths was so weak that I lumped them (as well as the even less successful rump Mensheviks) in with the “Others” colour of Duma seats.

This has led to the situation in which, taken together, the representatives on lists of the ethnic minorities were stronger in the Duma than the nation-wide Russian opposition parties. I’ve lumped them together in the overview because they’re simply too many. A great deal of the remaining national minorities in the Russian FR are Muslims, but not all. Among the Muslim groups, Alimardan Topchubashov’s Presidential campaign has done wonders to revive the moribound Ittifaq al-Muslimin, who has nevertheless scored much less percent and seats in the Duma elections than in the Presidential ones because in the Duma elections, they had to contend against more aggressively secessionist Young Turkic / Turanist parties on the one hand and socialist Muslim election lists like the one led by Sultan-Galiev and Waxitov. The SR faction in the Duma has been contacting many of these minority representatives in an attempt to integrate them into their SR-PSLP coalition. Some of the minority parties are willing to play along – but that support is going to come with strings attached, and these strings have the word “autonomy” written all over them. The only group of minority lists which does not call for autonomy, or at least not universally, for this is one of their main bones of contention, is the group of Jewish lists. Some of them saw themselves as closely related to Social Democracy, others were ideologically more pluralist or vague or even conservative. They diverged from one another heavily in their views regarding Zionism, the idea of a Jewish federative republic, the idea of personal autonomy following Austro-Marxist ideas, and a rejection of any such separation; they disagreed on educational matters, they had disagreed on the war, and they continued to disagree over economic policies. As Vladimir Zenzinov, the Socialist Revolutionary candidate who tried to gather a majority in the Duma which would elect him as Prime Minister, would find out, negotiations with each of the Jewish lists separately would go rather well, but bringing more than one of them into the common team would prove nigh on impossible.

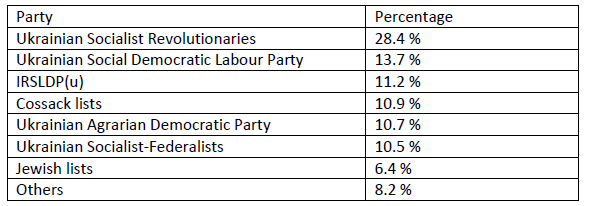

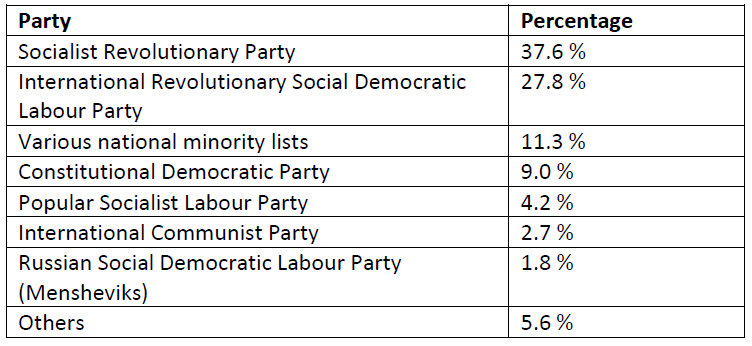

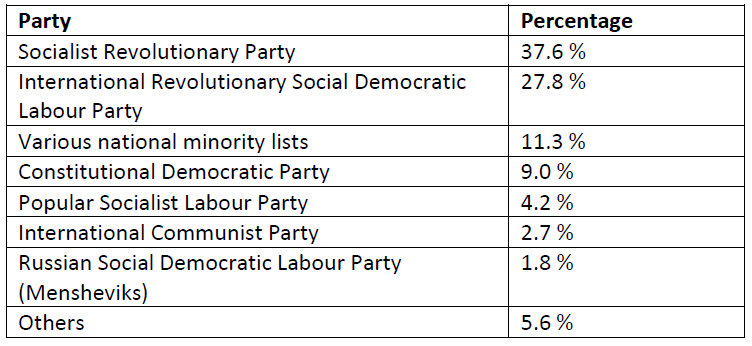

Here is an overview of the seats obtained by the various parties:

And so, as 1918 ends, Russia has a parliament of its own, but this parliament has not elected a Prime Minister yet. In the meantime, Martynov’s Roskom continues as the largest federative republic’s interim government…

As you will have already noted in the coverage of the elections of the other federative republics and of the Union Presidency, the UoE general elections of December 1918 are characterized by a very heavy overweight / hegemony of the Leftist side of the political spectrum. Now, “Left” and “Right” are not anthropological constants, of course, they are historical, and just as they emerged, they can also dissipate. The old Marxist (and Narodnik, too!) utopia of a classless society which has overcome its antagonisms is one such hypothetical state. Is this really what is happening here? Only time will tell. History has shown us countless examples of revolutions in which the Left dominated very much, bringing forth political landscapes which started out occupying only what is Left of Centre, but in the following years and decades, some parties shifted rightwards so that more of the spectrum typical for modern developed societies is occupied. (Portugal comes to mind: ever since the Carnation Revolution, the country’s political scene is divided between Social Democrats, Socialists and Communists. Only, the “Social Democrats” are by now economically neoliberal and socially conservative, thus by all means a conservative party, the Socialists are moderate, slightly left-of-centre Social Democrats, and the Communists have travelled the route over Eurocommunism to becoming the sort of separated left wing of social democracy which parties like the German Linke, the Dutch Socialists, the Spanish Unidos Podemos etc. also occupy.) So, is this what happens here? Will one of the parties shift to the right and restore the balance we are so familiar with? (If so, then it appears that the SRs are predestined for this course, given how they’re already perceived as the “moderates” with Avksentiev as their President-Elect, and the less class-antagonistic, more harmony-oriented ideological outlook of Narodnichestvo would facilitate this, too.) On the other hand, the balance we are familiar with is very much a child of the short 20th century, which ITTL is only just beginning. Before the Great War, with limited suffrage in many countries, the old bourgeois alternative between Liberals and Conservatives had been more prominent (while certainly already decaying), and the trends of our current century may point in other directions, too, what with the disintegration of the 20th century Left.

Only the continuation of this TL will tell if 1918 is going to be an exception or the new norm. I am very interested in your opinion on this matter, dear readers, of course!

But for the moment, it must be stated that this is clearly a trend from OTL which I could not have ignored if I had wanted to (which I didn’t *grin*). It would be wrong to say that Russia follows this trend – it is much more adequate to say that Russia has created this 1917-1918 trend. The federative republics we have covered so far have their own local histories, but in the large tilt to the Left, they are following something which has begun in many places, but certainly erupted first in Petrograd and took a number of escalating steps there.

Many others have written much more adequately about this trend than I could ever hope to. I will limit myself to pointing out where the divergences of TTL have picked up on OTL developments and where they deviated from them. By the time of the PoD, the massive dynamics had already been in full motion: the utter collapse of a delegitimized tsarism (and with it the entire discourse on “constitutional monarchy” vs “republicanism” etc.), the self-empowerment of the masses (embodied in the soviets), the exhaustion with regards to the war, the economic collapse (which was also a collapse of various economic policies which had dominated pre-war politics: market- and capital investment-oriented development of industry and large scale agriculture on the one hand side, militarized state dirigism on the other. If you’re looking at trends observable in the local duma elections of the summer of 1917 IOTL, and then in the Constituent Assembly elections of December 1917 OTL, the continuous leftward dynamics can’t be overseen, and the same goes for the implosion of the Russian Right. By the times of the CA election, the Kadets are the most right-wing option which is still at least barely visible – before the Great War, any ordinary educated Russian would clearly have placed the Kadets on the Centre-Left of Russia’s political landscape…

ITTL, the process is accelerated and channeled at once when Prince Lvov’s coalition (of Kadets, Octobrists, independents and one Trudovik: Kerensky) bluffs, their bluff is called, and the soviets take over power temporarily and with a good degree of political legitimacy, without a single shot being fired, and they call CA elections. The CA elections of TTL’s June 1917 thus already mirror OTL’s December 1917 outcome – with the exception of the absence of Menshevik and Right SR delegitimisation through support of a bourgeois-acting Provisional Government, an October Revolution and thus of Bolshevik hegemony over the country and over the RSDLP. Like IOTL, the SRs have inevitably been the largest party, and so they, who never led a government IOTL, have done so ITTL since July 1917. They deliver on their main promise – land reform – which secures their rural powerbase. Although attacks from the Left are no less fierce than IOTL, the SRs are in a solid-enough position to embrace those of their critics who are willing to be embraced in the November Realignment – and ruthlessly persecute the rest, both on the Right, which has discredited itself another time in August 1917 with its ties to the botched Kornilov Coup, and on the Left (remaining Bolsheviks and anarchists). Over the course of 1918, this very broad socialist coalition was faced with more military defeats, economic crisis, the need to relocate to Moscow, and ultimately the reversal of the war, having been able to triumph at the end, which still leaves the situation of the population quite as destitute as before, only now they no longer have to fear to get sent into trenches to die there. Divisions between SRs and SDs became more and more nuanced throughout 1918, and so the two parties face each other as the electoral giants of the new Republic – both on the Union level and on the Russian level. Given the conditions they had to work in, they were relatively successful together. This is not the only, and maybe not even the primary reason why they’re dominating the elections: the fact that the extreme Right is now tainted once again with its collaboration with Markov and the latter’s downfall, the fact that the Kadets are at a loss for how to adapt to the new situation, and not least the fact that the government, through the instrument of the VChK, has been oppressing and imprisoning any groups who are seen as “saboteurs” who want to overthrow the new system. (As has been noted, this is a specifically Russian situation, since the republics who had already enjoyed autonomy at the time of the November Realignment clearly objected to the VChK poking their noses into their republic’s affairs.)

Actually, this is probably the moment where I should describe how the Russian Federative Republic came into being and what its constitutional structures are. The Russian FR is an exceptional case indeed – it is the only federative republic whose constitution was not drafted by a national council or assembly of some sort or other, and whose “integration” into the Union of Equals did not require a Concordance, state contract or anything else of this sort. In some sense, this is logical, because the Russian Federative Republic, unlike all others, was not created by an autochtonous group seeking national self-determination. It was created after everyone else (well, before the Bessarabians and the Belorussians, but still) had got their own federative republic. It was created out of a desire for constitutional systematicity – the Union of Equals was to be composed of federative republics, and so “rest Russia” had to form one, too. (This is not to say that there had never been Russian nationalism. There certainly has been, but its objective had been different. In many cases, it had been directly opposed to what happened in 1917 and 1918 which ultimately led to the establishment of a Russian FR.)

The constitution of the Russian FR was drafted by the very same Constitutional Assembly in Petrograd (and later Moscow) which also drafted the constitution of the Union – only when the Russian constitution was discussed and voted on, the representatives of the already-autonomised republics were required to leave the plenary. (The Russian FR’s constitution has therefore been voted on by Northern Caucasian, Belorussian and Bessarabian delegates, too, because their federative republics were formed only later.) It stipulated that the Russian FR was to be a parliamentary socialist republic, where the Duma would vote on penal and civil laws, general taxes, education, infrastructure and the like, whilst local, regional and republic-wide soviets would set the rules of the economic game, provide social security and healthcare, administer common resources etc. The soviets would appoint a number of permanent committees to oversee day-to-day economic manamgement, whereas the Duma would elect a Prime Minister, who would appoint ministers to run the respective segments of the republican administration. When it was established in November 1917, it was determined that the elections to the next Duma (delegates to the soviets could be elected and recalled at will, without guaranteed terms, by those who delegated them) would be held on the same day on which Union-wide Presidential elections would also be held. In the meantime, Russian-only affairs would be handled by a sub-committee of the People’s Commission (popularly referred to as Roskom). Roskom, which over the course of 1918 had not been exactly very important since most decisions were still taken by the Commission at large, was officially chaired by a Bread Menshevik, Alexander Martynov (i.e. someone from the smallest and weakest group in the November Realignment coalition).

The effect of this late and involuntary “birth of a national republic” caused a lot of lack of popular knowledge in Russia about the exact differences between the Duma and the old Constituent Assembly, between the Russian Prime Minister and the President of the Union etc. This way, the Presidential election system, whose effect is that of a concentration on a handful, often only two, main contenders, heavily influenced electoral behavior in the Russian Duma elections, too, especially since people voted for both on the same day in the same voting booth.

The Russian Duma is elected in a mixed system of personalized proportional representation (like (West) Germany’s system after 1949) – but since the vast majority of Russian voters are not yet extremely familiar with the minutiae of the differences between Union Presidency, Federative Republican Duma and all that, there is a very strong tendency to vote for the Duma list of the same Party whose candidate they also voted for President. This, again, strengthens the IRSDLP(u) and the SRs at the detriment of smaller parties.

The abysmal performance of the Kadets and Trudoviks (there is nothing of any substance left standing to the Right of the Kadets at the moment) as well as of Bukharin’s remaining rump Bolsheviks (who renamed themselves into International Communist Party) and Julius Martov’s rump Mensheviks (who simply called themselves Russian Social Democratic Labour Party now that the name had been abandoned both by the ICP and the IRSDLP(u)) has other reasons, too:

The Kadets are still struggling to find their position in the new system. They oppose most of the socio-economic and political transformations which happened after Lvov’s demission, but for obvious reasons they also don’t rally for a counter-revolution. They did not want the new constitution and they objected heavily (but without any success) to the referendum held on it, but now they have no choice but to play by the new rules. They had not openly supported Kornilov’s coup, but also not credibly distanced themselves from it. They had not collaborated with Markov’s puppet regime, but the resistance against it had been formed and led by others. They had always supported the war effort, but now the radical Left, who had been full of defeatists, was basking in the glory of victory. Their economic policy agenda utterly unrealistic to be implemented under the soviet system, but the Kadets also knew they couldn’t take on the soviets single-handedly (no matter how strong they would become in the Duma – well, they would not become strong…). Their social powerbase had, in part, turned to the parties of the Left, or was turning away from politics, and to some degree was even emigrating, seeking better opportunities to pursue their happiness in North or South America. Pavel Milyukov’s days at the helm of the party were numbered, everyone knew that. Leading his party into defeat in the Duma elections would be his last “accomplishment” – even before the official results were announced, he resigned from his position.

The Popular Socialist Labour Party (or short: Trudoviks) was suffering from their lack of structures in the territory. In tsarist times, they had been the outermost leftist representatives tolerated in the toothless Duma, also serving as a mouthpiece for other, suppressed groups – their moment of glory had been the soviet interregnum in May 1917 when Alexander Kerensky had led the People’s Commission together with Victor Chernov and Fyodor Dan. But there had been little time to prepare for the elections to the Constituent Assembly in 1917, and the Trudoviks, who appeared soft now, had not been able to put a foot on the ground either in the countryside, where peasant councils formed, utterly dominated by the SRs, or in the industrialised cities, where workers councils were shifting ever leftwards within the framework of Russia’s Social Democracy. The November Realignment left them in the opposition, where they shared many of the problems described with regards to the Kadets above. There was one important difference, though: the Trudoviks would be represented in the new Union government, and they would stand at the SRs’ side in a new Duma coalition. The Trudoviks were not yet just a Kerensky election club – politicians like Alexander Zarudny had too much of a profile for that to happen. But they were a small faction.

Between the Kadets, Trudoviks, SRs and IRSLDP(u), there was really no political space left for the last Mensheviks who have not joined the IRSLDP(u). In the December 1918 elections, they were ultimately reduced to the status of a splinter party. After this humiliating failure, its more profiled and ambitious personnel would soon join leave and the party would ultimately dissolve – Irakli Tsereteli, for example, would remain affiliated with the Georgian (Menshevik) Social Democrats (who had founded the Federation of Independent Social Democrats) and represent Georgia in the Council of the Union (more on this institution in a later update); Alexander Potresov, Fyodor and Lydia Dan and many others joined the Trudoviks, while Julius Martov, for whom the Trudoviks were decidedly too un-internationalistic and theoretically under-sophisticated, would become one of the “independent” political thinkers of the next decade (and obtain a professorship at the Lomonosov).

Bukharin’s International Communists (=former Bolsheviks), on the other hand, had suffered from serious obstruction throughout the duration of the war. When the war ended, the situation became a little more relaxed and the ICP was not hindered to participate in the Duma elections – but it had been marginalized too long, suffered too many losses (to the IRSDLP(u) as well as to imprisonment) and been infiltrated too heavily by undercover VChK agents. Its showing at the booths was so weak that I lumped them (as well as the even less successful rump Mensheviks) in with the “Others” colour of Duma seats.

This has led to the situation in which, taken together, the representatives on lists of the ethnic minorities were stronger in the Duma than the nation-wide Russian opposition parties. I’ve lumped them together in the overview because they’re simply too many. A great deal of the remaining national minorities in the Russian FR are Muslims, but not all. Among the Muslim groups, Alimardan Topchubashov’s Presidential campaign has done wonders to revive the moribound Ittifaq al-Muslimin, who has nevertheless scored much less percent and seats in the Duma elections than in the Presidential ones because in the Duma elections, they had to contend against more aggressively secessionist Young Turkic / Turanist parties on the one hand and socialist Muslim election lists like the one led by Sultan-Galiev and Waxitov. The SR faction in the Duma has been contacting many of these minority representatives in an attempt to integrate them into their SR-PSLP coalition. Some of the minority parties are willing to play along – but that support is going to come with strings attached, and these strings have the word “autonomy” written all over them. The only group of minority lists which does not call for autonomy, or at least not universally, for this is one of their main bones of contention, is the group of Jewish lists. Some of them saw themselves as closely related to Social Democracy, others were ideologically more pluralist or vague or even conservative. They diverged from one another heavily in their views regarding Zionism, the idea of a Jewish federative republic, the idea of personal autonomy following Austro-Marxist ideas, and a rejection of any such separation; they disagreed on educational matters, they had disagreed on the war, and they continued to disagree over economic policies. As Vladimir Zenzinov, the Socialist Revolutionary candidate who tried to gather a majority in the Duma which would elect him as Prime Minister, would find out, negotiations with each of the Jewish lists separately would go rather well, but bringing more than one of them into the common team would prove nigh on impossible.

Here is an overview of the seats obtained by the various parties:

And so, as 1918 ends, Russia has a parliament of its own, but this parliament has not elected a Prime Minister yet. In the meantime, Martynov’s Roskom continues as the largest federative republic’s interim government…