You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Der Kampf: The Rise and Fall of the Austrian Führer

- Thread starter Tanner151

- Start date

As a heads up everyone I am roughly 50-60% done with the next chapter. Hope to have it out by the end of January if not before but as always there’s an asterisk there when it comes to a release schedule.

I have largely completed what Hitler’s Cabinet will look like when he comes to power in 1934 (99% I’ve confirmed that is the year when Hitler becomes Führer) as well as key military leaders. Due to Hitler being Army Minister he’s going to be meeting a lot of high ranking officers so I needed to do that research now. And many officers he meets now in the Bundesheer will be key players in the later Volkswehr.

My big issue that I’m running into is… who will be the sole Admiral of the Austrian Navy (Volksmarine)?

I honestly was going to go with Georg von Trapp but did not pursue that due to his anti-Nazi stance OTL which means he would be anti-Sozinat here ITTL. Now von Trapp will in Austria until 1938 like OTL and will help establish a foundation for the Volksmarine but will not lead it during war.

Does anyone have a suggestion of a historical Austrian who would be in his 40s/50s/60s to command the Volksmarine during the 1940s? I’ve struggled finding one so may have to go with an original character for the spot.

Next chapter will be a good chunk of 1932. I’m thinking there will be a mini time jump to late 1933 for the chapter after next.

Hope everyone has had a good and safe start to the new year. See y’all then.

I have largely completed what Hitler’s Cabinet will look like when he comes to power in 1934 (99% I’ve confirmed that is the year when Hitler becomes Führer) as well as key military leaders. Due to Hitler being Army Minister he’s going to be meeting a lot of high ranking officers so I needed to do that research now. And many officers he meets now in the Bundesheer will be key players in the later Volkswehr.

My big issue that I’m running into is… who will be the sole Admiral of the Austrian Navy (Volksmarine)?

I honestly was going to go with Georg von Trapp but did not pursue that due to his anti-Nazi stance OTL which means he would be anti-Sozinat here ITTL. Now von Trapp will in Austria until 1938 like OTL and will help establish a foundation for the Volksmarine but will not lead it during war.

Does anyone have a suggestion of a historical Austrian who would be in his 40s/50s/60s to command the Volksmarine during the 1940s? I’ve struggled finding one so may have to go with an original character for the spot.

Next chapter will be a good chunk of 1932. I’m thinking there will be a mini time jump to late 1933 for the chapter after next.

Hope everyone has had a good and safe start to the new year. See y’all then.

If Hungary gets absorbed into the Sozinat empire, how about [landlocked] Admiral Miklós Horthy, as a bone to reassure the Hungarians that they're considered equal partners in the new Austro-Hungarian state? Presumably he would not be trusted with actual command, since his new position is a downgrade, but owing to the relative lack of Austrian naval assets he's not in a position to cause trouble and he can basically be reduced to a figurehead while his sozinat deputies report directly to the Volkswehr's General Staff.Does anyone have a suggestion of a historical Austrian who would be in his 40s/50s/60s to command the Volksmarine during the 1940s? I’ve struggled finding one so may have to go with an original character for the spot.

Georg von Trapp could be blackmailed into serving in a similar capacity from retirement as that of August von Mackensen, showing up at official events to maintain the fiction of continuity but otherwise excluded from active command.

Another option is Rudolf Singule, who had a reasonably successful career as a U-boat commander in the Austro-Hungarian Navy, earning no small amount of decorations and eventually serving in the Kriegsmarine as a U-boat instructor.

Last edited:

Perhaps, the celeb WWI naval aviator Gottfried Freiherr von Banfield or even if less likely the Navy Physician Julius von Wagner-Jauregg, they may be some worth options...Does anyone have a suggestion of a historical Austrian who would be in his 40s/50s/60s to command the Volksmarine during the 1940s? I’ve struggled finding one so may have to go with an original character for the spot.

Speaking of Horthy, what would be interesting would be the roles of the likes of Gyula Gombos, Bela Imredy and Laszlo Bardossy here as they were amongst the more fascist-adjacent figures in Horthy's regime IOTL and all that.If Hungary gets absorbed into the Sozinat empire, how about [landlocked] Admiral Miklós Horthy, as a bone to reassure the Hungarians that they're considered equal partners in the new Austro-Hungarian state? Presumably he would not be trusted with actual command, since his new position is a downgrade, but owing to the relative lack of Austrian naval assets he's not in a position to cause trouble and he can basically be reduced to a figurehead while his sozinat deputies report directly to the Volkswehr's General Staff.

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Three

Santiago, Chile

Republic of Chile

January 1932

Santiago, Chile

Republic of Chile

January 1932

Garth Culpepper wiped the sweat from his brow, cursing the backwards weather. It was January damnit! It should be cold! Instead his clothes were soaked through with sweat, the ceiling fan above spun in lazy circles, creaking with each turn, yet did very little to actually alleviate the heat.

Outside his hotel room he got a fair view of downtown Santiago. The roads were filled with honking cars and the sidewalks brimming with people going about their day. Other than the signs being in Spanish it wasn’t that different than London.

Other than the bloody heat.

“Uncomfortable, Mister Walsh?” asked the man in nondescript clothing who sat across the table from Culpepper. “Is the weather not to your liking?” The Chilean man who name was Señor Schmidt smiled. Schmidt, as the name suggested, was of German stock. His family had moved to Chile following the Franco-Prussian War. The sandy hair and blue eyes were a stark contrast to a majority of the other Chileans Culpepper had seen since he had arrived in-country a few months ago.

“I prefer warm and cool days, not stroke-inducing heat or frostbite-causing cold.” Culpepper fanned himself with a paper folder, gifting him momentary bliss. The room smelled of sweat and cheap cologne.

“My country is not for everyone,” Schmidt said, his English impeccable. Schmidt shrugged then leaned forward. “Tell me, Mister Walsh, when will you leave for England?”

“Tomorrow. Don’t fear, señor, this ill-kept Anglo-Saxon will be out of your government’s hair soon enough.”

Schmidt shrugged. “It’s not that we don’t appreciate your efforts these past few weeks, but there is a… hesitance amongst my government about the charity of foreign powers.”

Culpepper’s eyes narrowed in annoyance.

“That charity you are so hesitant about is there to keep your government from falling to another coup.” Schmidt seemed to bite his cheek at that.

Culpepper didn’t deign to go into another reason why the United Kingdom and the United States had sold three frigates and two minesweepers to Chile. The Great Depression had cut deep into government revenues, hence cuts had to be made. Military budgets had been a favorite of many nations worldwide, therefore the U.S. Navy and Royal Navy had sold several Great War-era ships to friendly nations around the world. The money Chile had used to purchase them barely covered the cost of sailing them to South America, but it did lessen the cost of maintenance both navies had to perform, allowing them to direct their attention to more modern vessels of war coming out of production.

America and Britain weren’t the only two countries doing what some were calling ‘Strength via Sale.’ Reports reaching MI6 were that Japan was increasing weapon shipments to the Manchu Empire in exchange for a consistent flow of natural resources and cheap labor while helping develop infrastructure in North Sakhalin for cheap oil. And it wasn’t just the Japanese, the Soviets were doing it too. One of the reasons Culpepper had come to Chile was to track down rumors of Soviet shipments of weapons to communist revolutionaries.

Thus far he had found very little evidence of direct Soviet involvement but there was just enough breadcrumbs to hint at a possibility that had thus far not been revealed. It would be up to Quex to decide how they would proceed from there.

“Regardless, Mister Walsh,” Schmidt said, “Your government’s aid is more than welcome.”

“I’m glad, Señor Schmidt. It might be the last for some time.”

“Oh?” The Chilean mumbled in a neutral tone.

“Other matters are demanding my government’s attention. Germany is looking increasingly fragile every day, the Soviets are inciting revolutionary movements across the globe, Japan is likely readying itself for another war in Asia, and Austria has fallen to fascism.”

Schmidt nodded slowly. “And I know that my government will assist any way it can if the need arises.”

“His Majesty’s government thanks yours, sir. Unofficially of course.”

“Of course, Mister Walsh.”

Culpepper nodded and turned from the Chilean official to stand beneath the ceiling fan. Schmidt left moments later, their business concluded.

Going into the small hotel kitchen, he poured a glass of water. Culpepper sighed. He couldn’t wait until he returned to England. He only hoped his next assignment had better weather.

Outside his hotel room he got a fair view of downtown Santiago. The roads were filled with honking cars and the sidewalks brimming with people going about their day. Other than the signs being in Spanish it wasn’t that different than London.

Other than the bloody heat.

“Uncomfortable, Mister Walsh?” asked the man in nondescript clothing who sat across the table from Culpepper. “Is the weather not to your liking?” The Chilean man who name was Señor Schmidt smiled. Schmidt, as the name suggested, was of German stock. His family had moved to Chile following the Franco-Prussian War. The sandy hair and blue eyes were a stark contrast to a majority of the other Chileans Culpepper had seen since he had arrived in-country a few months ago.

“I prefer warm and cool days, not stroke-inducing heat or frostbite-causing cold.” Culpepper fanned himself with a paper folder, gifting him momentary bliss. The room smelled of sweat and cheap cologne.

“My country is not for everyone,” Schmidt said, his English impeccable. Schmidt shrugged then leaned forward. “Tell me, Mister Walsh, when will you leave for England?”

“Tomorrow. Don’t fear, señor, this ill-kept Anglo-Saxon will be out of your government’s hair soon enough.”

Schmidt shrugged. “It’s not that we don’t appreciate your efforts these past few weeks, but there is a… hesitance amongst my government about the charity of foreign powers.”

Culpepper’s eyes narrowed in annoyance.

“That charity you are so hesitant about is there to keep your government from falling to another coup.” Schmidt seemed to bite his cheek at that.

Culpepper didn’t deign to go into another reason why the United Kingdom and the United States had sold three frigates and two minesweepers to Chile. The Great Depression had cut deep into government revenues, hence cuts had to be made. Military budgets had been a favorite of many nations worldwide, therefore the U.S. Navy and Royal Navy had sold several Great War-era ships to friendly nations around the world. The money Chile had used to purchase them barely covered the cost of sailing them to South America, but it did lessen the cost of maintenance both navies had to perform, allowing them to direct their attention to more modern vessels of war coming out of production.

America and Britain weren’t the only two countries doing what some were calling ‘Strength via Sale.’ Reports reaching MI6 were that Japan was increasing weapon shipments to the Manchu Empire in exchange for a consistent flow of natural resources and cheap labor while helping develop infrastructure in North Sakhalin for cheap oil. And it wasn’t just the Japanese, the Soviets were doing it too. One of the reasons Culpepper had come to Chile was to track down rumors of Soviet shipments of weapons to communist revolutionaries.

Thus far he had found very little evidence of direct Soviet involvement but there was just enough breadcrumbs to hint at a possibility that had thus far not been revealed. It would be up to Quex to decide how they would proceed from there.

“Regardless, Mister Walsh,” Schmidt said, “Your government’s aid is more than welcome.”

“I’m glad, Señor Schmidt. It might be the last for some time.”

“Oh?” The Chilean mumbled in a neutral tone.

“Other matters are demanding my government’s attention. Germany is looking increasingly fragile every day, the Soviets are inciting revolutionary movements across the globe, Japan is likely readying itself for another war in Asia, and Austria has fallen to fascism.”

Schmidt nodded slowly. “And I know that my government will assist any way it can if the need arises.”

“His Majesty’s government thanks yours, sir. Unofficially of course.”

“Of course, Mister Walsh.”

Culpepper nodded and turned from the Chilean official to stand beneath the ceiling fan. Schmidt left moments later, their business concluded.

Going into the small hotel kitchen, he poured a glass of water. Culpepper sighed. He couldn’t wait until he returned to England. He only hoped his next assignment had better weather.

Vienna, Austria

Republic of Austria

January 1932

Republic of Austria

January 1932

“Vaterland, wie bist du herrlich.

Gott mit dir, mein Österreich!”

Konrad Leichtenberg sang along to the lyrics of Sei gesegnet ohne Ende, feeling the stirring of patriotism thumping in his chest. Below in the Heldenplatz, the aptly named Heroes’ Square in front of the Hofburg Imperial Palace, marched rank after rank of the Sturmkorps and Sturmwache. Their black boots seemed to shake the earth with their coordinated marching. Each paramilitary man held a torch in one hand, giving an almost medieval look to the evening display.

Past Heldenplatz, the Volksgarten was filled with ecstatic citizenry, waving small national and party flags as a sign of patriotism and loyalty to the new coalition. Leichtenberg could see the crowd assembled went far back enough to reach the grounds of the Rathaus, Parliament and the Chancellery.

The air seemed charged, electric even. The sense of malaise that had hovered over Austria since the announcement of Creditanstalt’s bankruptcy was at long last coming to an end. Strength had returned to power. A government of vision, of action, had come to the halls of Ballhausplatz 2.

That was the official line of course. No legislation had been passed as of yet. Dollfuss had only become chancellor days ago. Yet Dollfuss had promised results and several bills were working their way through committee in the newly sworn in National Council. It would not be long before it was sent on to the Federal Council to be rubber stamped then dispatched to the president’s desk to be signed into law. Immediately after the chancellor would countersign and begin enacting said law to put Austria on the path of recovery.

Eyes flicked down back to Heldenplatz, Leichtenberg watched the procession continue. Two banners flying from the front rank of each detachment. One was the Austrian flag while a party flag flew beside it. White VF letters on a black field for the Sturmkorps while the Sturmwache flew the red Krückenkreuz upon a white circle amidst a black field.

That very same symbol was slipped around Leichtenberg’s left arm via an armband. It gave him pride, a sense of purpose in this world since his firing from the Foreign Ministry years earlier. He stood off to the right and behind the Führer while Hitler himself stood beside Chancellor Dollfuss on the balcony overlooking the martial display. The two had hands clasped and raised to the adoration of the cheering crowds. Fatherland Front and Social Nationalism, two sides of the same coin, united together to save the country.

President Miklas stood beside them and offered hesitant clapping for appearances sake, but Leichtenberg could tell the Austrian head of state was bitter. The man more than likely wished he was there supporting another Christian Social chancellor rather than a pair of Austrofascists.

Though Hitler seemed enthused to the adoring crowds, Leichtenberg could tell Austria’s new Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army was notably restrained emotionally. None of the chest thumping fire-and-brimstone rhetoric or displaying his well-known aura of charisma, merely the presented facade of a uniformed bureaucrat going about his job.

While undoubtedly glad to once more wield influence and power in government, Leichtenberg knew the Führer was only partially sated by the scraps thus far doled out by Dollfuss.

Hitler’s ambition was infectious, a sense of hunger for power that enraptured the rank-and-file of the ÖSNVP. They would follow him into death, Leichtenberg knew that. Hitler was the lifeblood of the movement. It was unfathomable to picture Social Nationalism without him at its head.

They party members would overthrow Dollfuss in a heartbeat to elevate Hitler to the chancellorship but the Führer had been silent on the matter. Leichtenberg knew playing second fiddle chafed at Hitler’s pride but the Führer knew he did not yet have the support of a majority of the Volk. As of now they stood fully behind their Millimetternich, putting their hopes and dreams upon his shoulders.

Dollfuss might succeed, he might fail. Regardless, when the time came Hitler would seize the moment and turn Austria into the country it should be rather than what it currently was.

For now Leichtenberg simply observed, watching Hitler play his part. The blue-gray uniform many in the Party’s hierarchy wore was devoid of ornamentation barring a Krückenkreuz armband on the left arm and the Iron Cross of Merit on his chest.

To Leichtenberg, Hitler looked every centimeter the image of a strong statesman. Serious in demeanor, with bold and daring ideas, all fueled by an ambitious craving for power to fulfill a national desire for revenge. Dollfuss might be Austria’s dictator in all but name but Leichtenberg knew the new Unity Bloc government would be rife with compromise and debate which would slow the country’s recovery.

The nation needed strong leadership that only Hitler’s Führerprinzip could provide.

Soon enough, Leichtenberg thought with anticipation. After all, one must run before he can sprint.

Gott mit dir, mein Österreich!”

Konrad Leichtenberg sang along to the lyrics of Sei gesegnet ohne Ende, feeling the stirring of patriotism thumping in his chest. Below in the Heldenplatz, the aptly named Heroes’ Square in front of the Hofburg Imperial Palace, marched rank after rank of the Sturmkorps and Sturmwache. Their black boots seemed to shake the earth with their coordinated marching. Each paramilitary man held a torch in one hand, giving an almost medieval look to the evening display.

Past Heldenplatz, the Volksgarten was filled with ecstatic citizenry, waving small national and party flags as a sign of patriotism and loyalty to the new coalition. Leichtenberg could see the crowd assembled went far back enough to reach the grounds of the Rathaus, Parliament and the Chancellery.

The air seemed charged, electric even. The sense of malaise that had hovered over Austria since the announcement of Creditanstalt’s bankruptcy was at long last coming to an end. Strength had returned to power. A government of vision, of action, had come to the halls of Ballhausplatz 2.

That was the official line of course. No legislation had been passed as of yet. Dollfuss had only become chancellor days ago. Yet Dollfuss had promised results and several bills were working their way through committee in the newly sworn in National Council. It would not be long before it was sent on to the Federal Council to be rubber stamped then dispatched to the president’s desk to be signed into law. Immediately after the chancellor would countersign and begin enacting said law to put Austria on the path of recovery.

Eyes flicked down back to Heldenplatz, Leichtenberg watched the procession continue. Two banners flying from the front rank of each detachment. One was the Austrian flag while a party flag flew beside it. White VF letters on a black field for the Sturmkorps while the Sturmwache flew the red Krückenkreuz upon a white circle amidst a black field.

That very same symbol was slipped around Leichtenberg’s left arm via an armband. It gave him pride, a sense of purpose in this world since his firing from the Foreign Ministry years earlier. He stood off to the right and behind the Führer while Hitler himself stood beside Chancellor Dollfuss on the balcony overlooking the martial display. The two had hands clasped and raised to the adoration of the cheering crowds. Fatherland Front and Social Nationalism, two sides of the same coin, united together to save the country.

President Miklas stood beside them and offered hesitant clapping for appearances sake, but Leichtenberg could tell the Austrian head of state was bitter. The man more than likely wished he was there supporting another Christian Social chancellor rather than a pair of Austrofascists.

Though Hitler seemed enthused to the adoring crowds, Leichtenberg could tell Austria’s new Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army was notably restrained emotionally. None of the chest thumping fire-and-brimstone rhetoric or displaying his well-known aura of charisma, merely the presented facade of a uniformed bureaucrat going about his job.

While undoubtedly glad to once more wield influence and power in government, Leichtenberg knew the Führer was only partially sated by the scraps thus far doled out by Dollfuss.

Hitler’s ambition was infectious, a sense of hunger for power that enraptured the rank-and-file of the ÖSNVP. They would follow him into death, Leichtenberg knew that. Hitler was the lifeblood of the movement. It was unfathomable to picture Social Nationalism without him at its head.

They party members would overthrow Dollfuss in a heartbeat to elevate Hitler to the chancellorship but the Führer had been silent on the matter. Leichtenberg knew playing second fiddle chafed at Hitler’s pride but the Führer knew he did not yet have the support of a majority of the Volk. As of now they stood fully behind their Millimetternich, putting their hopes and dreams upon his shoulders.

Dollfuss might succeed, he might fail. Regardless, when the time came Hitler would seize the moment and turn Austria into the country it should be rather than what it currently was.

For now Leichtenberg simply observed, watching Hitler play his part. The blue-gray uniform many in the Party’s hierarchy wore was devoid of ornamentation barring a Krückenkreuz armband on the left arm and the Iron Cross of Merit on his chest.

To Leichtenberg, Hitler looked every centimeter the image of a strong statesman. Serious in demeanor, with bold and daring ideas, all fueled by an ambitious craving for power to fulfill a national desire for revenge. Dollfuss might be Austria’s dictator in all but name but Leichtenberg knew the new Unity Bloc government would be rife with compromise and debate which would slow the country’s recovery.

The nation needed strong leadership that only Hitler’s Führerprinzip could provide.

Soon enough, Leichtenberg thought with anticipation. After all, one must run before he can sprint.

Vienna, Austria

Republic of Austria

February 1932

Republic of Austria

February 1932

The clinking of champagne glasses filled the offices of the Rossauer Barracks. Nearly five hundred people were present, all Party members or their dates. Not only was much of the Party’s leadership present, so too was every Social Nationalist councilor in Parliament as were every regional Party Kapitelleiter. It was a night of celebration from the leadership all the way down to the rank-and-file.

There was dancing, music and laughter. It was a pleasant evening for Olbrecht who shook the hands of Party loyalists. The night was filled with much back-patting and firm embraces between comrades. After years of struggling for power in the political wilderness of the mid- and late-1920s, the ÖSNVP had at last seized the reins. Considering the Party had been founded just a little over seven years ago in a derelict Viennese warehouse, it was impressive that they were now the second most powerful political party in the nation.

It was cathartic to see how far the ÖSNVP had come, thought Olbrecht. From a movement of exiles to coalition partners in a fascist government. The Führer was no longer a government outcast. He was, in fact, part of said government. Though he bore the title of Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army, everyone here saw Hitler as their commander, their leader who would guide Austria into a better tomorrow. Dollfuss was merely the result of coalition building, his chancellorship a price they paid for being where they were now.

“Franz!” Shouted Walter Riehl. The man stumbled over, face red from drink. Olbrecht plastered on a false smile. He did care much for Riehl, he had just never enjoyed the man’s company, but Olbrecht couldn’t deny the influence Riehl had on the Vienna City Council and its accompanying Landtag.

While Vienna was widely known as ‘Red Vienna’ due to its strong support for the Social Democrats, and to a lesser degree the communists, Riehl led Social Nationalist efforts in the nation’s capital. A powerful man in the Party, influential in the Führer’s inner circle.

It irked Olbrecht that someone who had not fought in the Great War was given such an influential place in the Party.

Calm, Franz, calm, he thought. The war was thirteen years past now. It pained him and reminded him of his own mortality, but there would be a time when all members of the Movement would not know the hardship of loss that followed the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain. Social Nationalism would endure far into the future, but only if their efforts in the present bore fruit.

Riehl, von Starhemberg, Olbrecht, they were all but cogs in the machine. Chess pieces to be moved around to better achieve Hitler’s goals. The Führer’s vision was that of the Party. For all intents and purposes Hitler was the Party and the Party was Hitler.

“Ahh, Walter,” Olbrecht said. “Pleasure as always.”

“Indeed.” The man held out his hand and Olbrecht grabbed it to give a perfunctory shake. He leaned into Olbrecht’s ear, the smell of expensive alcohol wafting into Olbrecht’s nose as the man spoke. “We’re finally here, Franz! The Pfrimer Affair is a forgotten matter now. The future's looking bright, eh.”

“That it is, Walter. That it is.” Olbrecht patted the man’s shoulder and quickly disengaged, wiping his hand on his suit.

“That’s not very nice of you,” murmured a familiar voice.

Olbrecht smiled as he turned around. “Margarete, I’m glad you made it.”

Margarete Olbrecht, his sister and family matriarch since their father’s death in the war’s immediate aftermath, still retained her grace and beauty in spite of the years. However he did note streaks of silver were beginning to sprinkle throughout her red-brown hair. They were both getting older, he reflected sourly. Her clothing was reserved, with white silk gloves reaching up to her elbows. She smiled, white teeth dazzling any who would look at her. They leaned in for a quick embrace and a kiss on the cheek.

“It’s been too long, Franz.”

“That it has.” He smiled again. It was truly good to see her. Their relationship had been stationed for years but she had reached out to him following the last election and the back and forth had helped thaw any icy discontent previously there.

“Come,” she said. “There’s someone I want you to meet.”

Thinking it was another one of her aristocratic female associates Olbrecht sighed. “Margarete,” he exasperated.

“What? Oh no, don’t worry. I haven’t found your future wife yet. Though I will soon.” She winked at him. “There’s someone else I want to introduce to you. Someone Adi might find of interest.”

“Margarete,” he repeated again, exasperation growing. “He hasn’t even looked at another woman since Liese-“

“Good God, Franz! Do you think I spend my days daydreaming about finding women for powerful men to bed?”

“Well…”

Margarete laughed. A rich, throaty chuckle more appropriate for a teasing barmaid than a woman of high society. It was also the laugh of a woman who was wickedly smart, who knew how to play powerful men and to insert her desires into theirs. Olbrecht knew she was capable of this, yet went along like a lost puppy, simply glad to have her back in his life.

“Come, come. The gentleman,” she stressed the word, “you’ll meet is an interesting fellow. Someone I found doing advertisements for a wireless company out in Linz. He has such a way with words. Apolitical as far as I know but he has a sharp tongue and an even sharper wit. You could use him, Franz. You and the Party.”

“Since when have you cared about the Party, Margarete?”

“Times change and I must change with them if I’m to stay afloat.”

Interest piqued, Olbrecht allowed his sister to guide him to a balcony overlooking Türkenstraße. A man stood there, dressed in a nice albeit worn suit. Not a man of means, but most Austrians could say the same in the current economic climate.

“Vinzenz!” Margarete called out. The man turned, proving to be no older than thirty.

Too young to have fought in the war then, he thought sourly.

Despite his youth, the man was quite good looking with dark black hair combed over just so as to appear dashing with a clean shaven face revealing a strong jaw. Dark brown eyes twinkled as he looked at the approaching Olbrechts. He raised a glass of champagne in salute.

“Margarete,” the man’s voice boomed. “And this must be the war hero Franz Olbrecht!” The man’s hand shot out. It was then Olbrecht noted the man was missing an earlobe. “An honor and a privilege to make your acquaintance, sir.”

Unlike with Riehl, Olbrecht gave the man a firm handshake of respect. By how the man stood and how he spoke made Olbrecht certain of one thing.

“You served in the Army, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir. Corporal Vinzenz Breslauer. 92nd Olmütz State Rifle Brigade, 13th Infantry Regiment.”

“Lieutenant Colonel Franz Olbrecht. 87th Brigade, 21st Regiment.” Olbrecht raised an eyebrow at him. “Aren’t you a little young to have served?”

“Joined in mid ‘18, just before my seventeenth birthday. The recruiters were so desperate that they hardly noticed the forged paperwork. Either that or they didn’t care.” The man shrugged nonchalantly.

Olbrecht laughed and looked at his sister. “I like this man already.”

“I knew you would,” she said behind a half-smile, champagne glass raised to her lips.

From inside the Barracks the band ceased playing.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” came a booming voice via a microphone. “I am honored to present tonight Austria’s newest Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army, the Founder of Social Nationalism and the Führer of our Party: Adolf Hitler!”

Loud clapping and enthusiastic whooping followed. The band began playing a patriotic tune.

“So I hear you work for a wireless company out in Linz and somehow attracted my sister’s attention. How did that happen?”

“I was the campaign manager for Franz Langoth’s run for the mayoral office. I helped organize the media storm that might have had a role to play in ousting Josef Gruber as Linz’s Mayor.”

“Might have?” Margarete chided playfully. “Vinzenz, you’re too humble.” She turned to Olbrecht. “Vinzenz here was able to convince the electorate of our fair city to not only cast out that Social Democrat Gruber for your man Langoth but also helped swing a dozen SPÖ and CS seats on the city council to ÖSNVP.”

“His campaign was that effective?”

“Mhmm. Exceptional. He used paper and radio with flawless precision that got people out to vote Social Nationalist when otherwise they would have voted for someone else or just as likely have stayed home.”

Olbrecht grunted before turning to Breslauer. “How come I’ve never heard of you?”

Breslauer shrugged by Margarete answered for him.

“You know how much of a self-important pompous ass eager for the limelight Langoth is. He took the credit and Breslauer here didn’t seem to care.”

“I didn’t,” the dark haired man said. “I did my job and got paid. Other than that, who cares.”

An unambitious yet effective propagandist who helped oust an incumbent in a safe SDAPÖ mayoral seat for Linz’s first Social Nationalist.

“Come on, Vinzenz,” he found himself saying. “Let me introduce you to the Führer. He-“

Olbrecht stopped and glanced at Margarete. “Would you like to come with? I’m sure he has forgiven you. It’s been nearly a decade.”

Margarete’s smile chipped. “Oh, dear brother, you’re so far behind. I already met up with Adi, yesterday as a matter of fact. We're on good terms now. In fact you’re looking at one of the new economic policy advisors attached to the Army Ministry.”

“Really?” Olbrecht was stunned.

“Mhmm. I start next month with the ministry.”

“And he allowed that?”

“Yes. Adi let bygones be bygones, with a few caveats attached.”

“And they are?”

Margarete took on a resigned look. “Generous donations to the Party, of course. Several public speaking arrangements as well as individual meetings to bring in new wealthy donors for the cause, and, you’ll love this, Party membership.”

“You’re a Social Nationalist now?”

“As God as my witness. You’re looking at registered Party Member 37,144.” She sighed. “I’m not a fool nor am I blind. I see the way the wind is blowing, Franz. National Liberalism is all but dead. It has been for quite a while.”

Olbrecht grinned. His sister had at last seen sense. Sure she might have done it out of necessity but better late than never. It was good to have her on their side again.

“Come let’s celebrate! Today Social Nationalism runs Rossauer Barracks! Soon it will rule all of Austria!”

There was dancing, music and laughter. It was a pleasant evening for Olbrecht who shook the hands of Party loyalists. The night was filled with much back-patting and firm embraces between comrades. After years of struggling for power in the political wilderness of the mid- and late-1920s, the ÖSNVP had at last seized the reins. Considering the Party had been founded just a little over seven years ago in a derelict Viennese warehouse, it was impressive that they were now the second most powerful political party in the nation.

It was cathartic to see how far the ÖSNVP had come, thought Olbrecht. From a movement of exiles to coalition partners in a fascist government. The Führer was no longer a government outcast. He was, in fact, part of said government. Though he bore the title of Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army, everyone here saw Hitler as their commander, their leader who would guide Austria into a better tomorrow. Dollfuss was merely the result of coalition building, his chancellorship a price they paid for being where they were now.

“Franz!” Shouted Walter Riehl. The man stumbled over, face red from drink. Olbrecht plastered on a false smile. He did care much for Riehl, he had just never enjoyed the man’s company, but Olbrecht couldn’t deny the influence Riehl had on the Vienna City Council and its accompanying Landtag.

While Vienna was widely known as ‘Red Vienna’ due to its strong support for the Social Democrats, and to a lesser degree the communists, Riehl led Social Nationalist efforts in the nation’s capital. A powerful man in the Party, influential in the Führer’s inner circle.

It irked Olbrecht that someone who had not fought in the Great War was given such an influential place in the Party.

Calm, Franz, calm, he thought. The war was thirteen years past now. It pained him and reminded him of his own mortality, but there would be a time when all members of the Movement would not know the hardship of loss that followed the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain. Social Nationalism would endure far into the future, but only if their efforts in the present bore fruit.

Riehl, von Starhemberg, Olbrecht, they were all but cogs in the machine. Chess pieces to be moved around to better achieve Hitler’s goals. The Führer’s vision was that of the Party. For all intents and purposes Hitler was the Party and the Party was Hitler.

“Ahh, Walter,” Olbrecht said. “Pleasure as always.”

“Indeed.” The man held out his hand and Olbrecht grabbed it to give a perfunctory shake. He leaned into Olbrecht’s ear, the smell of expensive alcohol wafting into Olbrecht’s nose as the man spoke. “We’re finally here, Franz! The Pfrimer Affair is a forgotten matter now. The future's looking bright, eh.”

“That it is, Walter. That it is.” Olbrecht patted the man’s shoulder and quickly disengaged, wiping his hand on his suit.

“That’s not very nice of you,” murmured a familiar voice.

Olbrecht smiled as he turned around. “Margarete, I’m glad you made it.”

Margarete Olbrecht, his sister and family matriarch since their father’s death in the war’s immediate aftermath, still retained her grace and beauty in spite of the years. However he did note streaks of silver were beginning to sprinkle throughout her red-brown hair. They were both getting older, he reflected sourly. Her clothing was reserved, with white silk gloves reaching up to her elbows. She smiled, white teeth dazzling any who would look at her. They leaned in for a quick embrace and a kiss on the cheek.

“It’s been too long, Franz.”

“That it has.” He smiled again. It was truly good to see her. Their relationship had been stationed for years but she had reached out to him following the last election and the back and forth had helped thaw any icy discontent previously there.

“Come,” she said. “There’s someone I want you to meet.”

Thinking it was another one of her aristocratic female associates Olbrecht sighed. “Margarete,” he exasperated.

“What? Oh no, don’t worry. I haven’t found your future wife yet. Though I will soon.” She winked at him. “There’s someone else I want to introduce to you. Someone Adi might find of interest.”

“Margarete,” he repeated again, exasperation growing. “He hasn’t even looked at another woman since Liese-“

“Good God, Franz! Do you think I spend my days daydreaming about finding women for powerful men to bed?”

“Well…”

Margarete laughed. A rich, throaty chuckle more appropriate for a teasing barmaid than a woman of high society. It was also the laugh of a woman who was wickedly smart, who knew how to play powerful men and to insert her desires into theirs. Olbrecht knew she was capable of this, yet went along like a lost puppy, simply glad to have her back in his life.

“Come, come. The gentleman,” she stressed the word, “you’ll meet is an interesting fellow. Someone I found doing advertisements for a wireless company out in Linz. He has such a way with words. Apolitical as far as I know but he has a sharp tongue and an even sharper wit. You could use him, Franz. You and the Party.”

“Since when have you cared about the Party, Margarete?”

“Times change and I must change with them if I’m to stay afloat.”

Interest piqued, Olbrecht allowed his sister to guide him to a balcony overlooking Türkenstraße. A man stood there, dressed in a nice albeit worn suit. Not a man of means, but most Austrians could say the same in the current economic climate.

“Vinzenz!” Margarete called out. The man turned, proving to be no older than thirty.

Too young to have fought in the war then, he thought sourly.

Despite his youth, the man was quite good looking with dark black hair combed over just so as to appear dashing with a clean shaven face revealing a strong jaw. Dark brown eyes twinkled as he looked at the approaching Olbrechts. He raised a glass of champagne in salute.

“Margarete,” the man’s voice boomed. “And this must be the war hero Franz Olbrecht!” The man’s hand shot out. It was then Olbrecht noted the man was missing an earlobe. “An honor and a privilege to make your acquaintance, sir.”

Unlike with Riehl, Olbrecht gave the man a firm handshake of respect. By how the man stood and how he spoke made Olbrecht certain of one thing.

“You served in the Army, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir. Corporal Vinzenz Breslauer. 92nd Olmütz State Rifle Brigade, 13th Infantry Regiment.”

“Lieutenant Colonel Franz Olbrecht. 87th Brigade, 21st Regiment.” Olbrecht raised an eyebrow at him. “Aren’t you a little young to have served?”

“Joined in mid ‘18, just before my seventeenth birthday. The recruiters were so desperate that they hardly noticed the forged paperwork. Either that or they didn’t care.” The man shrugged nonchalantly.

Olbrecht laughed and looked at his sister. “I like this man already.”

“I knew you would,” she said behind a half-smile, champagne glass raised to her lips.

From inside the Barracks the band ceased playing.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” came a booming voice via a microphone. “I am honored to present tonight Austria’s newest Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Army, the Founder of Social Nationalism and the Führer of our Party: Adolf Hitler!”

Loud clapping and enthusiastic whooping followed. The band began playing a patriotic tune.

“So I hear you work for a wireless company out in Linz and somehow attracted my sister’s attention. How did that happen?”

“I was the campaign manager for Franz Langoth’s run for the mayoral office. I helped organize the media storm that might have had a role to play in ousting Josef Gruber as Linz’s Mayor.”

“Might have?” Margarete chided playfully. “Vinzenz, you’re too humble.” She turned to Olbrecht. “Vinzenz here was able to convince the electorate of our fair city to not only cast out that Social Democrat Gruber for your man Langoth but also helped swing a dozen SPÖ and CS seats on the city council to ÖSNVP.”

“His campaign was that effective?”

“Mhmm. Exceptional. He used paper and radio with flawless precision that got people out to vote Social Nationalist when otherwise they would have voted for someone else or just as likely have stayed home.”

Olbrecht grunted before turning to Breslauer. “How come I’ve never heard of you?”

Breslauer shrugged by Margarete answered for him.

“You know how much of a self-important pompous ass eager for the limelight Langoth is. He took the credit and Breslauer here didn’t seem to care.”

“I didn’t,” the dark haired man said. “I did my job and got paid. Other than that, who cares.”

An unambitious yet effective propagandist who helped oust an incumbent in a safe SDAPÖ mayoral seat for Linz’s first Social Nationalist.

“Come on, Vinzenz,” he found himself saying. “Let me introduce you to the Führer. He-“

Olbrecht stopped and glanced at Margarete. “Would you like to come with? I’m sure he has forgiven you. It’s been nearly a decade.”

Margarete’s smile chipped. “Oh, dear brother, you’re so far behind. I already met up with Adi, yesterday as a matter of fact. We're on good terms now. In fact you’re looking at one of the new economic policy advisors attached to the Army Ministry.”

“Really?” Olbrecht was stunned.

“Mhmm. I start next month with the ministry.”

“And he allowed that?”

“Yes. Adi let bygones be bygones, with a few caveats attached.”

“And they are?”

Margarete took on a resigned look. “Generous donations to the Party, of course. Several public speaking arrangements as well as individual meetings to bring in new wealthy donors for the cause, and, you’ll love this, Party membership.”

“You’re a Social Nationalist now?”

“As God as my witness. You’re looking at registered Party Member 37,144.” She sighed. “I’m not a fool nor am I blind. I see the way the wind is blowing, Franz. National Liberalism is all but dead. It has been for quite a while.”

Olbrecht grinned. His sister had at last seen sense. Sure she might have done it out of necessity but better late than never. It was good to have her on their side again.

“Come let’s celebrate! Today Social Nationalism runs Rossauer Barracks! Soon it will rule all of Austria!”

Last edited:

Von Trapp blackmailed is a good idea. Perhaps early on he’ll be like that until he leaves in ‘38. Rudolf Singule will now be the sole active admiral in the minuscule Volksmarine during the war. Thank you for the suggestion!Georg von Trapp could be blackmailed into serving in a similar capacity from retirement as that of August von Mackensen, showing up at official events to maintain the fiction of continuity but otherwise excluded from active command.

Another option is Rudolf Singule, who had a reasonably successful career as a U-boat commander in the Austro-Hungarian Navy, earning no small amount of decorations and eventually serving in the Kriegsmarine as a U-boat instructor.

Was thinking Banfield would switch to the Air Force and command air units in the former Yugoslavia or some such.Perhaps, the celeb WWI naval aviator Gottfried Freiherr von Banfield or even if less likely the Navy Physician Julius von Wagner-Jauregg, they may be some worth options...

When Hitler comes to power he and Horthy will have an understanding but that’ll change once war starts and Hitler’s power and greed grows.Speaking of Horthy, what would be interesting would be the roles of the likes of Gyula Gombos, Bela Imredy and Laszlo Bardossy here as they were amongst the more fascist-adjacent figures in Horthy's regime IOTL and all that.

Also btw this chapter was originally the first half of eh chapter I mentioned earlier. I published this half as its own thing because the original was getting too long. But the next chapter should be out by end of month still.

Hope y’all enjoy!

The Party uniform is mostly blue-gray. The Sturmwache wear it as well though with a wolf’s head flanked by lightning while the Staatschutz (SS) wear the same uniform with an upturned sword and crossed spears as their symbol.I could have sworn this was mentioned before but I don't care to go digging for it but what color are the uniforms are they Hugo boss black or something different

Edit- I mean the sturmwatch and stuff the ss expy

I realize now that everyone is wearing blue-gray. Huh. Might need to add pike gray in there somewhere or have the SS wear blue-gray with black or red trim.

What are y’all’s thoughts? Thankfully Book 2 is still in the edit phase so I can update uniform changes

What should the

Party uniform be:

Sturmwache uniform be:

Staatschutz (SS) uniform be:

So, 'd seem, that the Austrian Fuhrer has found his Austrian Goebbels...“Come, come. The gentleman,” she stressed the word, “you’ll meet is an interesting fellow. Someone I found doing advertisements for a wireless company out in Linz. He has such a way with words. Apolitical as far as I know but he has a sharp tongue and an even sharper wit. You could use him, Franz. You and the Party.”

Indeed...chile?

oh boy

If the events, as would appear, would follow their OTL course, the next years, for Chile, could have been very interesting albeit that in the Chinese senseThus far he had found very little evidence of direct Soviet involvement but there was just enough breadcrumbs to hint at a possibility that had thus far not been revealed. It would be up to Quex to decide how they would proceed from there.

I like the black uniform with red trim. Stands outThe SS should definitely have a Distinctive uniform to set them apart

Something not gray perhaps they coverngently pick black

Or maybe blue with a red trim

Either way it's got to be distinctive and stylish

Mhmm. It’s not the last we’ve seen of Chile. There are some butterflies, like the Anglo-American weapon sales, and more are to come.chile?

oh boy

Indeed he did. This is the Breslauer mentioned in the Prelude way back when.So, 'd seem, that the Austrian Fuhrer has found his Austrian Goebbels...

Indeed...

If the events, as would appear, would follow their OTL course, the next years, for Chile, could have been very interesting albeit that in the Chinese sense

Chile will have at least two more coups planned ITTL (not revealing just yet if they will succeed or not) but I will say this is a fate Chile is going to experience in the current story road map:

Well, I really, really, hope that what are depicted would be some Chilean troops adjoined to the Allies Armies (like Brazil OTL), in TTL Normandie equivalent... Cause, if not, then, would appear that TTL Chile would be royally screwed...Chile will have at least two more coups planned ITTL (not revealing just yet if they will succeed or not) but I will say this is a fate Chile is going to experience in the current story road map:

View attachment 883323

With regards to the armed organizations, are we talking about parade uniforms or field uniforms? Because that makes a big difference.The Party uniform is mostly blue-gray. The Sturmwache wear it as well though with a wolf’s head flanked by lightning while the Staatschutz (SS) wear the same uniform with an upturned sword and crossed spears as their symbol.

I realize now that everyone is wearing blue-gray. Huh. Might need to add pike gray in there somewhere or have the SS wear blue-gray with black or red trim.

What are y’all’s thoughts? Thankfully Book 2 is still in the edit phase so I can update uniform changes

What should the

Party uniform be:

Sturmwache uniform be:

Staatschutz (SS) uniform be:

(Sips tea)Well, I really, really, hope that what are depicted would be some Chilean troops adjoined to the Allies Armies (like Brazil OTL), in TTL Normandie equivalent... Cause, if not, then, would appear that TTL Chile would be royally screwed...

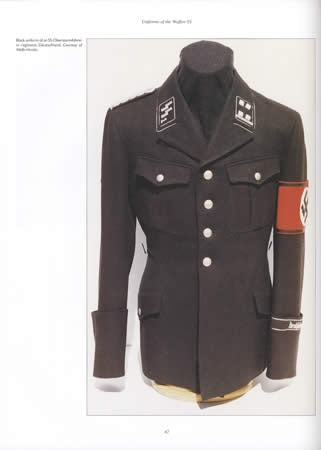

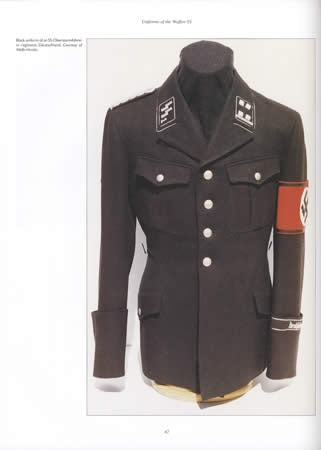

Field uniforms. Like this:With regards to the armed organizations, are we talking about parade uniforms or field uniforms? Because that makes a big difference.

I don't think the black and red is practical in the field (as the French learned that bright blue and red isn't good in World War I). Even the OTL Waffen-SS used normal feldgrau and later developed their Erbsenmuster. Yes, the Sturmwache is supposed to be snazzy and lavishly uniformed, but I'm not sure they'd wear parade ground uniforms into battle.(Sips tea)

Field uniforms. Like this:

But with the buttons, cuffing and rank insignia being red rather than silver. The SS don’t have field units (no Waffen-SS, just Sturmwache which is separate).

The blue-gray for the Sturmwache is Blue-gray but their military field uniform will be an early form of camo.I don't think the black and red is practical in the field (as the French learned that bright blue and red isn't good in World War I). Even the OTL Waffen-SS used normal feldgrau and later developed their Erbsenmuster. Yes, the Sturmwache is supposed to be snazzy, but I'm not sure they'd wear parade ground uniforms into battle.

Last edited:

How about dark red, with black armbands (since the Sozinat emblem seems to be a red and white cross on a black background) and rank boards with silver trim?I like the black uniform with red trim. Stands out

Share: