Vice principal,a principal wouldn't have cared that much that signing his discharge unless he crashed that Ferrari at the schoolWho can we replace him to play as Ferris Bueller's School Principal ITTL

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Hmmmm, I probably could concur that maybe not turn Rambo into an action franchise and instead the second and third Rambo movies are instead their own thing (like maybe combined with 1985's Commando, which is instead the first movie of that franchise)

Well TTL's Dean Rooney, I could suggest Everett McGill, Anthony Zerbe, Anthony Edwards, Tom Skerritt, Michael Ironside, James Tolkan, Miguel Ferrer and Kurtwood Smith (if he is more or less the same extreme Dean of Students in the OTL film) or maybe Frank MacRae (if TTL's Rooney is the less extreme version that @MNM041 advocated)

As for Rosemary and RFK Junior, I am still hopeful for Rosemary maybe following in her father and uncle's footsteps in the US Navy and becoming a helicopter pilot (maybe serving for a certain amount of years, until after TTL's Gulf War, by at which time she decides to take an honourable discharge, and from there, she'll decide another path), but maybe RFK Junior instead could seek his own path elsewhere or he could work in The Kennedy Center as @Uniquely Genius suggested.

Well TTL's Dean Rooney, I could suggest Everett McGill, Anthony Zerbe, Anthony Edwards, Tom Skerritt, Michael Ironside, James Tolkan, Miguel Ferrer and Kurtwood Smith (if he is more or less the same extreme Dean of Students in the OTL film) or maybe Frank MacRae (if TTL's Rooney is the less extreme version that @MNM041 advocated)

As for Rosemary and RFK Junior, I am still hopeful for Rosemary maybe following in her father and uncle's footsteps in the US Navy and becoming a helicopter pilot (maybe serving for a certain amount of years, until after TTL's Gulf War, by at which time she decides to take an honourable discharge, and from there, she'll decide another path), but maybe RFK Junior instead could seek his own path elsewhere or he could work in The Kennedy Center as @Uniquely Genius suggested.

Imagine if RFK Jr ended up becoming JFK Jr's agent in Hollywood.Hmmmm, I probably could concur that maybe not turn Rambo into an action franchise and instead the second and third Rambo movies are instead their own thing (like maybe combined with 1985's Commando, which is instead the first movie of that franchise)

Well TTL's Dean Rooney, I could suggest Everett McGill, Anthony Zerbe, Anthony Edwards, Tom Skerritt, Michael Ironside, James Tolkan, Miguel Ferrer and Kurtwood Smith (if he is more or less the same extreme Dean of Students in the OTL film) or maybe Frank MacRae (if TTL's Rooney is the less extreme version that @MNM041 advocated)

As for Rosemary and RFK Junior, I am still hopeful for Rosemary maybe following in her father and uncle's footsteps in the US Navy and becoming a helicopter pilot (maybe serving for a certain amount of years, until after TTL's Gulf War, by at which time she decides to take an honourable discharge, and from there, she'll decide another path), but maybe RFK Junior instead could seek his own path elsewhere or he could work in The Kennedy Center as @Uniquely Genius suggested.

Or he could go into sports, do wildlife photography, painting or even goes into teaching.Imagine if RFK Jr ended up becoming JFK Jr's agent in Hollywood.

I had this vague idea where he's played by Henry Winkler. Said version that Dean Rooney would also be less extreme, with his disdain for Ferris coming from the fact that he sees a younger version of himself in him and doesn't want to see throw his life away with his crazy antics.

Dean of Students, the School Principal wouldn't have cared that much that signing his discharge unless he crashed that Ferrari at the school.

Alright then genius, let's settle with Henry Winkler as Dean of Students Ed Rooney in Ferris Bueller's Day Off ITTL.For the role of Dean Rooney ITTL, I could suggest Everett McGill, Anthony Zerbe, Anthony Edwards, Tom Skerritt, Michael Ironside, James Tolkan, Miguel Ferrer and Kurtwood Smith (if he's more or less the same extreme Dean of Students IOTL) or maybe Frank McRae (if Dean Rooney ITTL is the less extreme version that @MNM041 advocated).

Hmmmm, I probably could concur that maybe not turn First Blood into an action franchise and instead make First Blood Part II and Part III as their own thing (like maybe combined with 1985's Commando, which is instead the first movie of that franchise).

As for Rosemary and Robbie, I am still hopeful for Rosemary maybe following in her father and uncle's footsteps in the US Navy and becoming a helicopter pilot (maybe serving for a certain amount of years, until after The Gulf War ITTL, by at which time she decides to take an honourable discharge, and from there, she'll decide another path), but maybe Robbie instead could seek his own path elsewhere or he could work in The Kennedy Center as @Uniquely Genius suggested.

Imagine if Robbie ended up becoming JFK, Jr.'s Hollywood Agent ITTL.

I second your suggestion to not make First Blood Part II and Part III an full-action genre, maybe follow the same formula of the first movie instead?Or he could go into sports, do wildlife photography, painting, or even goes into teaching.

Just to remind from the previous chapter written by Mr. President here that it's not RFK, Jr., it's Robert James Kennedy aka "Robbie", the youngest son of Jack and Jackie Kennedy ITTL. Do everyone agrees for Rosie and Robbie Kennedy to be enlisted in the US Army after graduating from Harvard University in the Late 80's ITTL? Or do they go straight to The Kennedy Center after graduating from Harvard University and work there to continue their father's advocacy for the arts ITTL.

Last edited:

First off, I didn't suggest that change for First Blood Part II and Part III. I was more of the suggestion that 1982's First Blood not be followed by a full-action sequel that turns Rambo into a full-action franchise, but instead in 1985, TTL's Commando instead is the first film of a full-action franchise that includes First Blood Part II and Part III, or at least elements of it.I second your suggestion to not make First Blood Part II and Part III an full-action genre, maybe action-drama instead?

Just to remind from the previous chapter written by Mr. President here that it's not RFK, Jr., it's Robert James Kennedy aka "Robbie", the youngest son of Jack and Jackie Kennedy ITTL. Do everyone agrees for Rosie and Robbie Kennedy to be enlisted in the US Army after graduating from Harvard University in the Late 80's ITTL? Or do they go straight to The Kennedy Center after graduating from Harvard University and work there to continue their father's advocacy for the arts ITTL.

Second of all, I acknowledge the mistake I made in thinking it was RFK Junior. Sorry everyone. I'll try to remember how to distinguish him, as RJK or simply Robbie in future.

And lastly, I never suggested Rosemary going into the US Army. I merely suggested her career path of following her father's footsteps by going into the US Navy, in which she becomes a helicopter pilot.

But I do agree that Robbie could go work straight for The Kennedy Center after graduating.

1. Agreed. One of my pop culture hot takes incoming: I've never been a fan of this film (especially compared to other Hughes/80s teen movies). I've always felt that the problematic content undercuts the positive themes that the film was going for.By the way, a few suggestions regarding pop culture.

1. When The Breakfast Club comes out, either have all of the students played by underage actors or none of them played by underage actors.

2. Just don't have Jeffery Jones be in Ferris Bueller when that movie comes out.

2. Yeah... Much as I enjoyed his performances as Ed Rooney and Charles Deetz in Beetlejuice, among others, I was pretty thoroughly disgusted when I heard about his MeToo stuff.

Yep.By the same token of what I've already mentioned, another suggestion is that nothing that qualifies as rape by fraud happens in Revenge of the Nerds.

Interesting question! I think Stallone will definitely be more famous for Rocky ITTL, but will still get the chance to work on other action franchises and such. TTL's Rambo could focus more on fighting the Khmer Rouge and the war crimes aspects as well.While popular culture is not my specialty, and I don't know if this has been brought up before in this thread or not, I was wondering whether Sylvester Stallone's Rambo trilogy has been made in this timeline. Of course, while the Cambodian War in this timeline shares some similarities with the OTL Vietnam War, it is also quite different given that it ended in a costly American victory, which in turn less radicalized the Hippies and New Left. This translated to a slightly better treatment of TTL Cambodian War veterans back in the US.

So while I think the first movie could still be made, albeit slightly modified from the OTL version, the second movie will be quite different. The third movie is still very plausible as the Soviets, even in this timeline, can't help themselves to not be involved in that country famed for being the "Graveyard of Empires." Then again, it could also be plausible that the entire trilogy didn't get made at this time, and Stallone is more famous for his role in the Rocky trilogy.

I. Love. This. Idea.I had this vague idea where he's played by Henry Winkler. Said version of Rooney would also be less extreme, with his disdain for Ferris coming from the fact that he sees a younger version of himself in him and doesn't want to see Ferris throw his life away with his crazy antics.

Not at all.I. Love. This. Idea.Do you mind if I steal it?

By the way, about my suggestion for The Breakfast Club, currently I'm leaning more towards the cast consisting entirely of people in their 20s, if only because I imagine that things would go smoother without having to deal with child labor laws.

Molly Ringwald's career would probably be fine even without The Breakfast Club, and maybe be Anthony Micheal Hall can avoid some of his issues here.

Molly Ringwald's career would probably be fine even without The Breakfast Club, and maybe be Anthony Micheal Hall can avoid some of his issues here.

Last edited:

Possibly, but I wouldn't necessarily hedge those bets. I mean, maybe people like I can't name due to them being current politics wouldn't be there, but I still think we're going to see at least some of them.Does anybody think that with the GOP not becoming as radicallized as IOTL, that the people who became media faces for them like Ann Coulter could lead different careers?

An RFK, Jr. that pulls an Anthony Bourdain and explores the world and cultures with no political aspirations sounds like something he could useOr he could go into sports, do wildlife photography, painting or even goes into teaching.

Last edited:

LordYam

Banned

For pop culture:

1.) Godfather: I don't actually mind the idea of a third one....just make it Michael vs Tom as originally intended. That would have been a far more tragic conflict, and it built on foreshadowing from the first two movies. Even if Tom is a traitor he can be acting to save the family. This leads to the tragic ending of the family and so drives home just how hollow it all was.

2.) DC comics: In OTL Marvel ripped off Darkseid to create Thanos; DC can do the same here. Like Thanos the replacement is still a formidable opponent.

1.) Godfather: I don't actually mind the idea of a third one....just make it Michael vs Tom as originally intended. That would have been a far more tragic conflict, and it built on foreshadowing from the first two movies. Even if Tom is a traitor he can be acting to save the family. This leads to the tragic ending of the family and so drives home just how hollow it all was.

2.) DC comics: In OTL Marvel ripped off Darkseid to create Thanos; DC can do the same here. Like Thanos the replacement is still a formidable opponent.

I personally liked the third one as it is. I mean, Michael trying his hardest to clean up the family business, just to get Kay and the kids back, only for it to fail horribly and him losing his daughter, and then dying alone. Tragic enough as it is. Though we can make Tom the villain here instead of whoever it was IOTL (I haven't watched the movie in years).1.) Godfather: I don't actually mind the idea of a third one....just make it Michael vs Tom as originally intended. That would have been a far more tragic conflict, and it built on foreshadowing from the first two movies. Even if Tom is a traitor he can be acting to save the family. This leads to the tragic ending of the family and so drives home just how hollow it all was.

Chapter 162

Disclaimer: I've been reading @KingSweden24's fabulous Bicentennial Man timeline here on the forum for a while and noticed that his most recent update also covers the 1982 Mexican Presidential election. Much of TTL's version of that event is similar to his. This is purely a coincidence; in fact, I wrote this update several months ago. I try to build up content for the pipeline in case I get busy and do not have time to work on new updates. That said, I just wanted to take this opportunity to give His Majesty a shout-out, as his work is excellent. If you have the time and interest and haven't already, I highly recommend you check it out! Without further adieu...

Chapter 162 - We Got the Beat - The 1982 Mexican Presidential Election

Above: Pablo Emilio Madero, candidate for the National Action Party (PAN)(left); Flag of Mexico (center); Javier García Paniagua, candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI)(right).

Above: Pablo Emilio Madero, candidate for the National Action Party (PAN)(left); Flag of Mexico (center); Javier García Paniagua, candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI)(right).

“See the people walking down the street

Fall in line just watching all their feet

They don't know where they want to go

But they're walking in time

They got the beat

They got the beat

They got the beat

Yeah, they got the beat” - “We Got the Beat” by the Go-Gos

“Authoritarian regimes are not the solution to overcoming economic and social problems in Latin America. Democracy is more effective in accomplishing these aims in a lasting way.” - Javier García Paniagua

“Mejor solo que mal acompañado.” - Mexican proverb, “It’s better to be alone than in bad company”.

If the early 1980s saw a positive reversal of fortunes for El coloso del norte (the United States), then that same period, unfortunately, saw another, running in the opposite direction for Mexico.

José López Portillo, fifty-eighth president of Mexico, in office since succeeding el gran reformador Carlos Madrazo in 1976, had won election in the first place by shedding the center-left “flavor” of Madrazo’s presidency in favor of a more decidedly centrist position, calling himself “neither of the left nor the right”. As had occurred so often in the history of his country, however, great movements of reform were almost inevitably followed by periods of reaction and backsliding. Portillo’s time in office was no different. Despite the successes at cleaning up Mexico City that his predecessor had found during the previous six years, as Portillo took office, he inherited a nation in the midst of a burgeoning economic crisis. This crisis was a localized version of a wider problem sweeping the entire region at the time: the Latin American Debt Crisis.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many Latin American countries, notably Brazil, Argentina, and yes, Mexico, borrowed huge sums of money from international creditors to aid in industrialization, especially infrastructure programs. These countries had soaring economies at the time, so the creditors were happy to provide loans. Initially, developing countries typically garnered loans through public routes like the World Bank. After 1973, private banks had an influx of funds from oil-rich countries which believed that sovereign debt was a safe investment. Unfortunately, Mexico borrowed against future oil revenues with the debt valued in US dollars, so that when the price of oil collapsed, so did the Mexican economy.

Between 1975 and 1982, Latin American debt to commercial banks increased at a cumulative annual rate of 20 percent. This heightened borrowing led Latin American countries to quadruple their external debt from US $75 billion in 1975 to more than $315 billion in 1983, or 50 percent of the entire region's gross domestic product (GDP). Debt service (interest payments and the repayment of principal) grew even faster as global interest rates surged, reaching $66 billion in 1982, up from $12 billion in 1975. As interest rates increased in the US and in Europe in 1979, the cost of debt payments also increased, making it harder for borrowing countries to pay back their loans. Deterioration in the exchange rate with the US dollar meant that Latin American governments ended up owing tremendous quantities of their national currencies, as well as losing purchasing power

As a result of these credit and finance issues, the Mexican people suffered from a number of hardships. Incomes (largely driven by exports) dropped, as did imports. Economic growth stagnated or went negative, causing recession. This led to increased unemployment at the same time that runaway inflation (from printing more and more pesos to try and make the debt payments) slashed the purchasing power of the middle class. Between 1976, when Portillo took office, through the end of his term in 1982, real urban wages in Mexico dropped anywhere between 20 and 40 percent. Meanwhile, in the US, losses to bankers were catastrophic. It is estimated that the combined losses to US banks from the Latin American Debt Crisis were more than the banking industry's entire collective profits since the nation's founding in 1776. Clearly, reforms were necessary on both sides of the Rio Grande.

To combat this crisis in his country, Portillo undertook an ambitious program to promote Mexico's economic development with revenues stemming from the discovery of new petroleum reserves in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco by Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the country's publicly owned oil company. In 1980, Mexico joined Venezuela in the “Pact of San José”, a foreign aid project to sell oil at preferential rates to countries in Central America and the Caribbean. The economic confidence that he fostered led to a short-term boost in economic growth, but by the time he left office, the economy had deteriorated further and gave way to an even more severe debt crisis and a sovereign default.

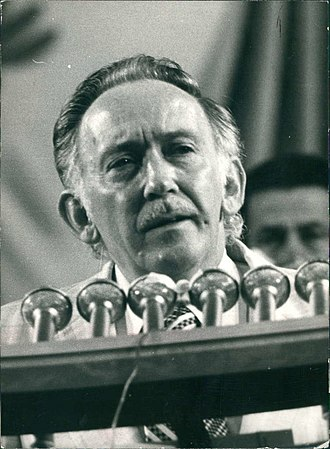

Above: José López Portillo, 58th President of Mexico. His term in office left a lot to be desired.

As if this weren’t enough to tarnish Portillo’s popularity and legacy, throughout his term, his critics also accused him of corruption and nepotism. Indeed, the Portillo administration was among the most notorious in recent Mexican history for the number of relatives of the President who held public office. He appointed his sister, Margarita López Portillo, head of the General Directorate of Radio, Television and Cinematography (RTC), his cousin Guillermo López Portillo as the first - and only - head of the newly created National Institute of Sport (INDE, which was dissolved in 1981), and his son José Ramón López Portillo (who was outright described by the President as “the pride of my nepotism”) was appointed Subsecretary of Programming and the Budget. His daughter, Paulina López Portillo, also debuted as a pop singer during his Presidency, and the First Lady Carmen Romano toured Europe with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Mexico City, which was founded and financed by the government of Mexico City through her initiative “to make fine arts education accessible to youths.”

For all his claims during the 1976 election of being “heir” to Madrazo’s legacy of reformist liberalism, to many, Portillo sure seemed like a step backward, into Mexico’s past. When fellow members of the Reform Liberal Party (PRL) tried to call him out for his corruption, Portillo demoted them into insignificance or arranged for them to be culled from the party altogether. This jefe politico behavior severely weakened the party apparatus, which was already struggling. The grassroots movement that had created it, whipped into existence by anger at the PRI establishment and carefully maintained by the charismatic leadership of Madrazo, had all but settled down. Madrazo’s political reforms, in the eyes of many, satisfied the PRL’s goals.

Perhaps the only major successes of Portillo’s term were to be found in the realm of foreign policy.

In 1977, following the death of Francisco Franco and restoration of Spanish democracy, Mexico resumed diplomatic relations with its one-time metropol. Two years later, Pope Stanislaus visited Mexico for the first time, strengthening Mexico’s relations with the Catholic world in general and the Pope’s native Poland in particular. 1981 saw Mexico host the Cancun Summit, a North-South dialogue which would be attended by 22 heads of state and government from industrialized countries (North) and developing nations (South). Despite Mexico’s economic issues, the summit promised closer relations with both the United States (the western hemisphere’s undisputed hegemon) and Brazil (its most rapidly rising power). The primary question to be decided over the next decade, all three nations agreed, was how best to grow all of their economies in a mutually beneficial manner. Both Brazil and Mexico were, at the time, largely driven by the export of commodities (coffee, soy, and other agricultural products in the former case; oil and minerals in the latter), while the United States was a highly developed industrial and service-based economy, with buckets of capital to be invested in education and technology. The leaders of all three countries at the time, Ulysses Guimarães for Brazil, Portillo for Mexico, and Robert F. Kennedy for America, believed that increased trade between them was of paramount importance, as was maintaining political stability throughout the hemisphere. They also agreed that the Organization of American States (OAS) was the proper forum to achieve these goals. Portillo supported Mo Udall and later, Robert Kennedy’s “good neighbor” approach to Latin America.

By the time the 1982 election approached, most of the PRL’s leaders sought reunification with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the latter of which had ruled Mexico since the 1920s. This would prevent the centrist vote from splitting, which might open the door to victory by either the conservative right (represented by the “National Action Party”) or the socialist left (represented by the “Unified Socialist Party of Mexico” and other groups). For the PRI leadership, this was less a reunification and more of a “homecoming”. Madrazo himself had once been a member of PRI, and had only founded his offshoot party after becoming overly frustrated by the party’s corruption and stagnation. Also unlike his predecessor, Portillo initially had no intention of allowing the “democratic process” to select his own successor. He wanted someone who would represent stability and, hopefully, solve the ongoing economic problems which Portillo himself was incapable of.

At first, the most likely candidate to win Portillo’s favor (and thus, the PRI nomination) appeared to be Jorge Díaz Serrano, former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Senator, and as of 1982, Director General of PEMEX. A long-term personal friend of Portillo, Diaz Serrano initially enjoyed a great deal of popularity with the Mexican people, especially during the oil boom of the late 1970s. On Diaz Serrano’s watch, Mexico became one of the world’s leading petroleum exporters, after all. However, in June 1981, international oil prices plummeted, and Díaz Serrano, without the authorization of the economic cabinet, consequently announced that Mexico would lower the prices of its own oil by 4 dollars per barrel. The controversy unleashed by Díaz Serrano's decision resulted in his resignation as Director General of PEMEX and, with it, the end of his presidential aspirations.

Above: Jorge Díaz Serrano (left) and Miguel de la Madrid (right), the two initial leading candidates to serve as PRI candidate in the 1982 presidential election.

The next major candidate was the PRI’s failed nominee from 1976, now Lopez Portillo’s Secretary of Programming and Budget, Miguel de la Madrid. Highly educated (boasting a post-graduate degree in administration from Harvard University), de la Madrid was seen as a technocrat and “whiz kid” (he was still only 48 years old in 1982) who might be able to put Mexico’s economy back on a productive path. Portillo actually preferred de la Madrid, and attempted to make him the nominee after Diaz Serrano was forced to drop out. But Portillo’s control over PRI was not as firm as he needed it to be in order to have his way. The party was once bitten, twice shy of de la Madrid after his loss six years prior. The faithful felt that he was too conservative, and too timid, lacking in the political skills necessary to hold the reins of power as el jefe politico supremo of the entire country. Ultimately, de la Madrid was not nominated a second time.

Finally, the last (and ultimately successful) candidate was Javier García Paniagua, National President of PRI, and one of its ultimate “insiders''. Panigua, the son of General Marcelino García Barragán, was a faithful reflection of the post-revolutionary political elite in Mexico, and was identified with the “populist” sector which was more inclined to uphold the orthodox discourse of the Mexican Revolution and to continue López Portillo's general policies. Panigua was the preferred candidate of most of the PRI’s bosses and even their everyday, rank-and-file members, due to his years of service and loyalty to the party apparatus. Despite the ongoing economic crisis and the fact that García Panigua’s nomination seemed to represent “more of the same '' for Mexico, the opposition to PRI remained divided as it had been for the past five decades. Without a strong, charismatic candidate to rally behind, the other parties ultimately put up fairly anemic resistance to García Paniagua. Him securing the PRI nomination was tantamount to winning the presidency. The general election, held on July 4th, 1982, confirmed this fact. García Paniagua won with more than 72% of the vote. To most pundits, both within Mexico and abroad, it appeared that the reforms of the Madrazo era had represented not the turning of a page, but rather, a brief gasp of genuine democracy crammed between repressive, corrupt one-party rule.

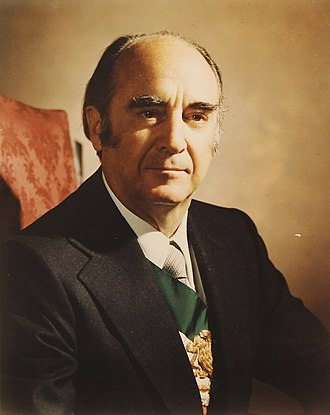

Above: Javier García Paniagua (PRI), elected 59th President of Mexico.

That is not to say, however, that the calls for reform and opposition to PRI domination died throughout the country, however. Far from it.

The National Action Party (PAN), the center-right party most closely identified with Christian Democracy and traditional, Catholic conservatism, grew its vote share to nearly 20% in 1982. Their candidate, Pablo Emilio Madero, finished a distant second, yes, but he had run a spirited campaign, and proved that conservatism, long thought dead after the Revolution, could still play a role in Mexican politics. Arnoldo Martinez Verdugo and the Unified Socialist Party attracted 5% of the vote, mostly winning support among industrial workers. Ironically, given the party’s name, they failed to properly unify the country’s left-wing. Another 5% of votes were split amongst another three socialist or communist parties, which had only recently been made legal under the Madrazo reforms. That said, doctrinaire socialism and especially communism were never going to take off in Mexico at this time. Proximity to the United States and the post-revolutionary consensus in the country made this virtually impossible.

No, if opposition to the PRI was going to form, then it would need to emulate the successful campaign waged by Madrazo himself back in 1970. And contrary to the deflated mood that many in the country felt after Panigua’s inauguration, there was a coalition that, if activated, could do the job. As the last vestiges of Madrazo’s PRL were dismantled and subsumed back into the PRI, many former reform-liberals refused to return to the fold. These middle and upper middle class voters detested the “patronizing” tone of García Paniagua and his supporters, who brazenly yearned for the return of “party unity” and the undoing of everything Madrazo had done to reform the country during his term in office. There were also laborers, both agricultural and industrial, who suffered most of the hardship imposed by the economic crisis. While many of these laborers had (reluctantly) backed Panigua and the PRI on the hopes that Panigua’s populism might translate to meaningful social welfare programs, they were swiftly dispelled of that notion. Panigua’s ideology was heavy on rhetoric, very light on policy specifics. Especially vocal in their opposition were university students and academics - the intelligentsia - who likewise wanted more genuine democracy in their beloved republic.

Though it would take several more years for these various factions to unify into a coherent opposition that could seriously challenge the PRI again, this time, when they did, under the leadership of another charismatic social democrat in 1988, the reforms that they enacted would be much more far-reaching and permanent, finally completing Mexico’s transformation from “party dictatorship” to “functioning democracy”.

Chapter 162 - We Got the Beat - The 1982 Mexican Presidential Election

“See the people walking down the street

Fall in line just watching all their feet

They don't know where they want to go

But they're walking in time

They got the beat

They got the beat

They got the beat

Yeah, they got the beat” - “We Got the Beat” by the Go-Gos

“Authoritarian regimes are not the solution to overcoming economic and social problems in Latin America. Democracy is more effective in accomplishing these aims in a lasting way.” - Javier García Paniagua

“Mejor solo que mal acompañado.” - Mexican proverb, “It’s better to be alone than in bad company”.

If the early 1980s saw a positive reversal of fortunes for El coloso del norte (the United States), then that same period, unfortunately, saw another, running in the opposite direction for Mexico.

José López Portillo, fifty-eighth president of Mexico, in office since succeeding el gran reformador Carlos Madrazo in 1976, had won election in the first place by shedding the center-left “flavor” of Madrazo’s presidency in favor of a more decidedly centrist position, calling himself “neither of the left nor the right”. As had occurred so often in the history of his country, however, great movements of reform were almost inevitably followed by periods of reaction and backsliding. Portillo’s time in office was no different. Despite the successes at cleaning up Mexico City that his predecessor had found during the previous six years, as Portillo took office, he inherited a nation in the midst of a burgeoning economic crisis. This crisis was a localized version of a wider problem sweeping the entire region at the time: the Latin American Debt Crisis.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many Latin American countries, notably Brazil, Argentina, and yes, Mexico, borrowed huge sums of money from international creditors to aid in industrialization, especially infrastructure programs. These countries had soaring economies at the time, so the creditors were happy to provide loans. Initially, developing countries typically garnered loans through public routes like the World Bank. After 1973, private banks had an influx of funds from oil-rich countries which believed that sovereign debt was a safe investment. Unfortunately, Mexico borrowed against future oil revenues with the debt valued in US dollars, so that when the price of oil collapsed, so did the Mexican economy.

Between 1975 and 1982, Latin American debt to commercial banks increased at a cumulative annual rate of 20 percent. This heightened borrowing led Latin American countries to quadruple their external debt from US $75 billion in 1975 to more than $315 billion in 1983, or 50 percent of the entire region's gross domestic product (GDP). Debt service (interest payments and the repayment of principal) grew even faster as global interest rates surged, reaching $66 billion in 1982, up from $12 billion in 1975. As interest rates increased in the US and in Europe in 1979, the cost of debt payments also increased, making it harder for borrowing countries to pay back their loans. Deterioration in the exchange rate with the US dollar meant that Latin American governments ended up owing tremendous quantities of their national currencies, as well as losing purchasing power

As a result of these credit and finance issues, the Mexican people suffered from a number of hardships. Incomes (largely driven by exports) dropped, as did imports. Economic growth stagnated or went negative, causing recession. This led to increased unemployment at the same time that runaway inflation (from printing more and more pesos to try and make the debt payments) slashed the purchasing power of the middle class. Between 1976, when Portillo took office, through the end of his term in 1982, real urban wages in Mexico dropped anywhere between 20 and 40 percent. Meanwhile, in the US, losses to bankers were catastrophic. It is estimated that the combined losses to US banks from the Latin American Debt Crisis were more than the banking industry's entire collective profits since the nation's founding in 1776. Clearly, reforms were necessary on both sides of the Rio Grande.

To combat this crisis in his country, Portillo undertook an ambitious program to promote Mexico's economic development with revenues stemming from the discovery of new petroleum reserves in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco by Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the country's publicly owned oil company. In 1980, Mexico joined Venezuela in the “Pact of San José”, a foreign aid project to sell oil at preferential rates to countries in Central America and the Caribbean. The economic confidence that he fostered led to a short-term boost in economic growth, but by the time he left office, the economy had deteriorated further and gave way to an even more severe debt crisis and a sovereign default.

Above: José López Portillo, 58th President of Mexico. His term in office left a lot to be desired.

As if this weren’t enough to tarnish Portillo’s popularity and legacy, throughout his term, his critics also accused him of corruption and nepotism. Indeed, the Portillo administration was among the most notorious in recent Mexican history for the number of relatives of the President who held public office. He appointed his sister, Margarita López Portillo, head of the General Directorate of Radio, Television and Cinematography (RTC), his cousin Guillermo López Portillo as the first - and only - head of the newly created National Institute of Sport (INDE, which was dissolved in 1981), and his son José Ramón López Portillo (who was outright described by the President as “the pride of my nepotism”) was appointed Subsecretary of Programming and the Budget. His daughter, Paulina López Portillo, also debuted as a pop singer during his Presidency, and the First Lady Carmen Romano toured Europe with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Mexico City, which was founded and financed by the government of Mexico City through her initiative “to make fine arts education accessible to youths.”

For all his claims during the 1976 election of being “heir” to Madrazo’s legacy of reformist liberalism, to many, Portillo sure seemed like a step backward, into Mexico’s past. When fellow members of the Reform Liberal Party (PRL) tried to call him out for his corruption, Portillo demoted them into insignificance or arranged for them to be culled from the party altogether. This jefe politico behavior severely weakened the party apparatus, which was already struggling. The grassroots movement that had created it, whipped into existence by anger at the PRI establishment and carefully maintained by the charismatic leadership of Madrazo, had all but settled down. Madrazo’s political reforms, in the eyes of many, satisfied the PRL’s goals.

Perhaps the only major successes of Portillo’s term were to be found in the realm of foreign policy.

In 1977, following the death of Francisco Franco and restoration of Spanish democracy, Mexico resumed diplomatic relations with its one-time metropol. Two years later, Pope Stanislaus visited Mexico for the first time, strengthening Mexico’s relations with the Catholic world in general and the Pope’s native Poland in particular. 1981 saw Mexico host the Cancun Summit, a North-South dialogue which would be attended by 22 heads of state and government from industrialized countries (North) and developing nations (South). Despite Mexico’s economic issues, the summit promised closer relations with both the United States (the western hemisphere’s undisputed hegemon) and Brazil (its most rapidly rising power). The primary question to be decided over the next decade, all three nations agreed, was how best to grow all of their economies in a mutually beneficial manner. Both Brazil and Mexico were, at the time, largely driven by the export of commodities (coffee, soy, and other agricultural products in the former case; oil and minerals in the latter), while the United States was a highly developed industrial and service-based economy, with buckets of capital to be invested in education and technology. The leaders of all three countries at the time, Ulysses Guimarães for Brazil, Portillo for Mexico, and Robert F. Kennedy for America, believed that increased trade between them was of paramount importance, as was maintaining political stability throughout the hemisphere. They also agreed that the Organization of American States (OAS) was the proper forum to achieve these goals. Portillo supported Mo Udall and later, Robert Kennedy’s “good neighbor” approach to Latin America.

By the time the 1982 election approached, most of the PRL’s leaders sought reunification with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the latter of which had ruled Mexico since the 1920s. This would prevent the centrist vote from splitting, which might open the door to victory by either the conservative right (represented by the “National Action Party”) or the socialist left (represented by the “Unified Socialist Party of Mexico” and other groups). For the PRI leadership, this was less a reunification and more of a “homecoming”. Madrazo himself had once been a member of PRI, and had only founded his offshoot party after becoming overly frustrated by the party’s corruption and stagnation. Also unlike his predecessor, Portillo initially had no intention of allowing the “democratic process” to select his own successor. He wanted someone who would represent stability and, hopefully, solve the ongoing economic problems which Portillo himself was incapable of.

At first, the most likely candidate to win Portillo’s favor (and thus, the PRI nomination) appeared to be Jorge Díaz Serrano, former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Senator, and as of 1982, Director General of PEMEX. A long-term personal friend of Portillo, Diaz Serrano initially enjoyed a great deal of popularity with the Mexican people, especially during the oil boom of the late 1970s. On Diaz Serrano’s watch, Mexico became one of the world’s leading petroleum exporters, after all. However, in June 1981, international oil prices plummeted, and Díaz Serrano, without the authorization of the economic cabinet, consequently announced that Mexico would lower the prices of its own oil by 4 dollars per barrel. The controversy unleashed by Díaz Serrano's decision resulted in his resignation as Director General of PEMEX and, with it, the end of his presidential aspirations.

Above: Jorge Díaz Serrano (left) and Miguel de la Madrid (right), the two initial leading candidates to serve as PRI candidate in the 1982 presidential election.

The next major candidate was the PRI’s failed nominee from 1976, now Lopez Portillo’s Secretary of Programming and Budget, Miguel de la Madrid. Highly educated (boasting a post-graduate degree in administration from Harvard University), de la Madrid was seen as a technocrat and “whiz kid” (he was still only 48 years old in 1982) who might be able to put Mexico’s economy back on a productive path. Portillo actually preferred de la Madrid, and attempted to make him the nominee after Diaz Serrano was forced to drop out. But Portillo’s control over PRI was not as firm as he needed it to be in order to have his way. The party was once bitten, twice shy of de la Madrid after his loss six years prior. The faithful felt that he was too conservative, and too timid, lacking in the political skills necessary to hold the reins of power as el jefe politico supremo of the entire country. Ultimately, de la Madrid was not nominated a second time.

Finally, the last (and ultimately successful) candidate was Javier García Paniagua, National President of PRI, and one of its ultimate “insiders''. Panigua, the son of General Marcelino García Barragán, was a faithful reflection of the post-revolutionary political elite in Mexico, and was identified with the “populist” sector which was more inclined to uphold the orthodox discourse of the Mexican Revolution and to continue López Portillo's general policies. Panigua was the preferred candidate of most of the PRI’s bosses and even their everyday, rank-and-file members, due to his years of service and loyalty to the party apparatus. Despite the ongoing economic crisis and the fact that García Panigua’s nomination seemed to represent “more of the same '' for Mexico, the opposition to PRI remained divided as it had been for the past five decades. Without a strong, charismatic candidate to rally behind, the other parties ultimately put up fairly anemic resistance to García Paniagua. Him securing the PRI nomination was tantamount to winning the presidency. The general election, held on July 4th, 1982, confirmed this fact. García Paniagua won with more than 72% of the vote. To most pundits, both within Mexico and abroad, it appeared that the reforms of the Madrazo era had represented not the turning of a page, but rather, a brief gasp of genuine democracy crammed between repressive, corrupt one-party rule.

Above: Javier García Paniagua (PRI), elected 59th President of Mexico.

That is not to say, however, that the calls for reform and opposition to PRI domination died throughout the country, however. Far from it.

The National Action Party (PAN), the center-right party most closely identified with Christian Democracy and traditional, Catholic conservatism, grew its vote share to nearly 20% in 1982. Their candidate, Pablo Emilio Madero, finished a distant second, yes, but he had run a spirited campaign, and proved that conservatism, long thought dead after the Revolution, could still play a role in Mexican politics. Arnoldo Martinez Verdugo and the Unified Socialist Party attracted 5% of the vote, mostly winning support among industrial workers. Ironically, given the party’s name, they failed to properly unify the country’s left-wing. Another 5% of votes were split amongst another three socialist or communist parties, which had only recently been made legal under the Madrazo reforms. That said, doctrinaire socialism and especially communism were never going to take off in Mexico at this time. Proximity to the United States and the post-revolutionary consensus in the country made this virtually impossible.

No, if opposition to the PRI was going to form, then it would need to emulate the successful campaign waged by Madrazo himself back in 1970. And contrary to the deflated mood that many in the country felt after Panigua’s inauguration, there was a coalition that, if activated, could do the job. As the last vestiges of Madrazo’s PRL were dismantled and subsumed back into the PRI, many former reform-liberals refused to return to the fold. These middle and upper middle class voters detested the “patronizing” tone of García Paniagua and his supporters, who brazenly yearned for the return of “party unity” and the undoing of everything Madrazo had done to reform the country during his term in office. There were also laborers, both agricultural and industrial, who suffered most of the hardship imposed by the economic crisis. While many of these laborers had (reluctantly) backed Panigua and the PRI on the hopes that Panigua’s populism might translate to meaningful social welfare programs, they were swiftly dispelled of that notion. Panigua’s ideology was heavy on rhetoric, very light on policy specifics. Especially vocal in their opposition were university students and academics - the intelligentsia - who likewise wanted more genuine democracy in their beloved republic.

Though it would take several more years for these various factions to unify into a coherent opposition that could seriously challenge the PRI again, this time, when they did, under the leadership of another charismatic social democrat in 1988, the reforms that they enacted would be much more far-reaching and permanent, finally completing Mexico’s transformation from “party dictatorship” to “functioning democracy”.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: An Update on the Iran-UAR War

Last edited:

Thank you@President_Lincoln Amazing work as always! Can't wait to see more!

Always do!Thank youGlad you enjoyed!

With regards to Mexico, @President_Lincoln , a certain disaster that will occur in Mexico in 1985 will play a large role in the downfall of the PRI, methinks...

What a happy coincidence! And thank you for the shout out, I’m flattered the author of one of the GOAT TLs of the site enjoys my work

Javier Garcia Paniagua being very much not what Mexico needed in 1982 certainly rings true, and I’m getting the sense that the ground is being laid for “successful Cuauhtémoc Cardenas” in 1988

(A very minor nitpick: Spanish naming conventions would have Mexico’s new President referred to as “Garcia Paniagua” or “Garcia;” the second surname is never used on its own)

Javier Garcia Paniagua being very much not what Mexico needed in 1982 certainly rings true, and I’m getting the sense that the ground is being laid for “successful Cuauhtémoc Cardenas” in 1988

(A very minor nitpick: Spanish naming conventions would have Mexico’s new President referred to as “Garcia Paniagua” or “Garcia;” the second surname is never used on its own)

Share: