------------------

Part 2: Social Programs and Land Reform

As expected of a man who made friendships with people such as Mário Soares, François Mitterrand and Willy Brandt during his long exile, Brizola made it one of his main priorities to combat the grotesquely high wealth inequality that led to so few notable people having more money than they knew what to do with and so many anonymous others who had absolutely nothing. Like any good social democrat, he believed that the way to solve or at least minimize this problem was through actions of the state. One of the easiest ways to do such a thing was to impose a policy of gradual systematic minimum wage increases that were also tied to inflation, ensuring that they didn't lose any real value (in US dollars) in case the Cruzado was suddenly devaluated. This policy was happily enforced by Minister of Labour Carlos Alberto Caó, and the minimum wage rose from US$ 58,00 in 1990 to US$ 142,00 in 1994 (1).

New social programs were created to help the poor, the most famous of them by far being the Bolsa-Escola, which consisted of a monthly concession of money (Cz$ 200,00 on average) to poor families as long as they sent their children to school, something that went hand in hand with Darcy Ribeiro's mass production of CIEPs all over Brazil and his other educational reforms. This program became the public face of the administration's war against poverty, and, while not as famous as, say, PRONASOL in Mexico, also won some international praise. While the monetary aid didn't look like much to, say, a middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo, too wealthy to qualify for it, it was a blessing for millions of people who lived below the poverty line all over Brazil, especially in the Northeast, and practically transformed the Old Caudillo into a deity in many places (2).

Many of the social advances desired by the Brizola administration depended on the construction and renovation of several infrastructure works, such as hospitals, sewage systems, electric grids (especially in the Northeast, where many houses had no electricity at all) amongst other things, something that went hand in hand with the Finance Ministry's developmentalist views and led to the creation of several jobs, which was a welcome bonus.

There are two important things to remember, however:

The first is that, no matter how good the federal government's intentions were, its aims would have never been reached were it not for the much needed support that was given by allied governors and mayors, the bulk of which were elected or reelected in 1990 and 1992, respectively.

The controvertially named Ernesto Che Guevara Municipal Hospital, located in Maricá, was built thanks to a partnership between the mayoralty and Brasília. It was inaugurated in 1995, just in time for Fidel Castro to take a good look at it during one of his many visits to Brazil (3).

The second is that many of the programs unveiled during the 1990s were guaranteed to do so thanks to the fact the Citizen's Constitution effectively guaranteed that they would be created in some shape or form. The Sistema Único de Saúde, or just SUS (Single Healthcare System) was born from the article which stated that every citizen deserved decent healthcare, and that the state as a whole was bound to fulfill that duty. Same thing goes for education, since it was very explicitly stated that the government had to provide it to every Brazilian man, woman and child (4). The Brizola administration can be credited with enforcing articles such as the ones already mentioned to the bitter end, and in the best, most effective way possible.

Speaking of, education always received special attention from Brasília, thanks to the fact that it was Brizola's biggest mark in both of his gubernatorial tenures (in Rio Grande do Sul and Rio de Janeiro, respectively) and the administration was absolutely filled to the brim with extremely competent people eager to reform Brazil's schools and universities, not only physically, but in the very way they and their classes were administrated. These universalist desires were handsomely reward legislatively through the Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação (Law of Basic Educational Guidelines), which, among several things, standardized educational practices and specified who was supposed to fund what (federal government funds universities, state government funds, municipal government funds the maintenance of primary schools, with salaries being paid by the state (5)).

All of this was accomplished thanks to the tireless work of many teachers and other intellectuals who would remain mostly anonymous, save a for a few glaring exceptions such as Paulo Freire and Darcy Ribeiro, legislators, activists, and many others.

What could have been.

Land redistribution was another one of the Brizola administration's many great ambitions to fulfill. This would be far from easy: for centuries, most of Brazil's agricultural lands were controlled by large, powerful landowners, and although these latifundiários could no longer hope to overthrow the Old Caudillo through a military coup like the one enacted against his brother-in-law more than two decades ago, they were still extremely wealthy and, most importantly, had enough allies in both houses of Congress, combined with their lobbying organization UCR, to provide a significant base of opposition to the federal government. Their main line of attack was that any attempt to address the country's long standing inequality would lead to an economic disaster, and that the administration's plans would infringe their right to hold private property. Naturally, leading reformists such as Francisco Julião, João Pedro Stédile and Chico Mendes disagreed with them quite fervently, and it seemed that the whole situation would result in an unbreakable stalemate.

Once again, the Citizen's Constitution comes in for the rescue.

Thanks to an article that very specifically allowed the government to expropriate lands that were deemed unproductive -- one of the left's most important victories in the Constituent Assembly -- the new administration could embark on its land reform program almost from day one. Under the supervision of minister Aldo Pinto, appointed specifically to help oversee and coordinate the efforts on this front, 1.200.000 families were settled on around 7.320.000 hectares of land between 1990 and 1993, and the families in question were given subsidies and low interest loans to ensure that they actually stayed in and developed their new properties (6). Beyond giving millions of people new jobs and easier lives, this policy also increased the production of basic foodstuffs such as various fruits, beans, lettuce, carrots, corn, potatoes, among many others, since these mall landholders didn't have the necessary capital to grow cash crops, but were perfectly capable of growing food for themselves and others, something that decreased the price of many staples over the years.

Predictably, these policies made the Brizola administration extremely popular, and many politicians, not just the president, had their careers reach new heights thanks to them.

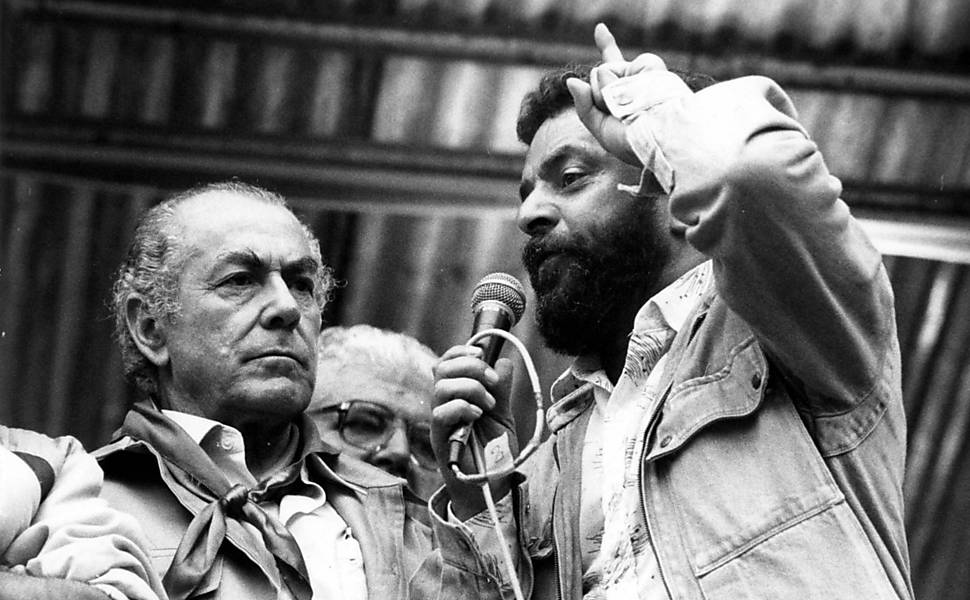

However, few would become as powerful, famous or popular as the Crown Prince.

------------------

(1)

Here's a table showing the evolution of the minimum wage in Brazil, in case the growth shown in this update seems unreasonable.

(2) This program is OTL, with all of its effects, the only difference being that it's called Bolsa Família instead.

(3) This hospital actually exists, but its construction began in 2014/2015, if I recall, under the municipal administration of Washington Quaquá. Here, the fact that Brazil is run by a personal friend of Fidel Castro and Guevara results in it being built much earlier.

(4) Just as OTL. Doesn't mean the federal government cares about enforcing it though.

(5) This is a substantial difference from OTL, where the municipalities have to pay for the maintenance

and salaries of those who work in the schools. Natutally, this puts poorer towns in quite a bind.

(6) The Fernando Henrique administration

did exactly this in the period between 1995 to 1998, but I doubt the resettled families were given proper support, since PFL (nowadays called DEM, but still as backward as ever) was a very important part of FHC's governing coalition. His vice-president, Marco Maciel, belonged to said party, for example.