Foreign Snapshot: El Fénix

------------------

Foreign Snapshot: El Fénix

It is still difficult, to this day, to describe the amount of sheer joy that the people of Mexico felt on December 1, 1988. That day, president Miguel de la Madrid, a member of the hated and seemingly invincible PRI, handed the presidential sash and all of the executive power that belonged to him to his successor, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Solórzano, who had somehow performed the impossible and brought an end to 59 years of single-party rule. The mood of the crowd of at least 500.000 people that gathered in the Zócalo to greet the new ruler of the most populous Spanish speaking country on Earth could only be described as completely delirious. Despite their somehow almost simultaneously stopped cheering to listen to every word he said, as if he was a Messiah who would lead them to an era of endless prosperity. And they certainly weren't the only ones in the nation who believed in that.

It was simply too much of a coincidence for that to not happen. The last time Mexico elected an opposition candidate was in... 1910, when none other than Francisco Madero, a hardworking and honest man who gave his life for his country, brought an end to the Porfiriato, a corrupt dictatorship that lasted for 35 years. As if that wasn't enough, it didn't even take an armed insurrection to get PRI out of power: all they needed to do was organize and vote for the right candidate. It was time for a new Revolution, one that manifested itself through laws and rallies, rather than vast armies and bloody battles.

To add to these wild (at the very least) expectations, the new president was the son of Lázaro Cárdenas, who was probably the best leader that the country had in the 20th century, with any attempt to criticize him being seen as a mortal sin. As such, Cuauhtémoc definitely had the "pedigree" to be an excellent ruler, and that was without the executive experience that he earned during the six years as governor of Michoacán, a state that his father also commanded. And since sons are supposed to be better than their fathers, well...

Poor Solórzano didn't meet his people's expectations. No one could.

After he took over, everyone found out the grim reality that PRI wasn't dead at all: they still had all of Mexico's state and local governments under their control, along with a substantial portion of the Chamber of Deputies that was enough to cause quite a headache, even if they didn't have an absolute majority, and worst of all, they had a crushing majority in the Senate, where they controlled 55 seats, while the FDN held 7 seats and PAN just 2 seats (1). The legislature, which for decades served only to rubber stamp decisions made by autocratic presidents, suddenly armed itself to the teeth and stood ready ready stonewall all of Cárdenas' initiatives and turn his life into a living hell.

How was he supposed to get anything done under these conditions?

It is often said that politics make strange bedfellows, and what Solórzano did on January 5, 1989 proved that. Simmering after being effectively forbidden from doing his work thanks to systematic opposition from PRI hardliners (dinosaurios) in Congress and in the states, the president had a meeting with Manuel Clouthier (2), Diego Fernández de Cevallos and Luis H. Álvarez, the highest-ranking panistas in the country. There was just one hurdle, however: their agenda was almost completely opposed to the one Cárdenas defended. While he and FDN were center-left and strongly secularistic, PAN was closely linked with conservative northern industrialists and catholics who opposed the many restrictions imposed on the Church. On any normal situation, these two groups would despise each other.

In spite of all of that, they agreed on one crucial thing that ensured that their alliance became a reality: they loathed PRI infinitely more than each other.

Left to right: Diego Fernández de Cevallos, Manuel Clouthier, Rosario Ibarra (a former communist and ally of the president), Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Luis H. Álvarez. As one can see, none of them are really happy about the recent turn of events.

Right after that alliance was made, president Cárdenas renewed his efforts to get at least one major piece of legislation through the dinosaurios that dominated the Senate. After weeks of negotiations, backroom deals, arm twisting and some honestly humiliating begging to priístas that he would never forget or forgive, he finally got his wish: on January 21 (3), the federal government announced the creation of the National Solidarity Program (PRONASOL) , an ambitious initiative that would later earn international praise and serve as a model for other Latin American countries to follow, particularly those who elected Pink Tide governments. It consisted of the channeling of federal resources to impoverished areas that were lacking in healthcare, education and basic infrastructure, ensuring that the people who lived in these regions experienced an improvement of their standard of living.

On the other hand, Cárdenas had to honor his end of the pact with PAN, whose assistance was critical in the creation of PRONASOL. To do that, he completed the privatization of Telmex, the state telephone company, which had started under Madrid's administration and concluded with it being sold to media mogul Joaquín Vargas Gómez, owner of the radio broadcaster MVS Comunicaciones (4). The banking industry which was nationalized in the last days of the troubled and corrupt presidency of José López Portillo, who preceded Miguel de la Madrid, was returned to the private sector. On the religious front, the Catholic Church was allowed to hold property once more, and priests were allowed to vote and wear their robes in public.

These measures did much to mitigate the concerns of international investors who, despite approving the downfall of a corrupt government (it's bad for business, after all) still had that kneejerk fear that a left-of-center administration would enact extremist policies regarding the economy. The end of the restrictions on the Church was also well received by the Mexican population in general, which was and still is highly religious, and was also seen as an important step towards the full democratization of the country. However, there were also sectors of the left, mostly radical university students, that were disillusioned with them, believing that the president was shifting himself to the right and abandoning his original projects. Some of them even began to call him "Cárdenas the Little", in contrast with his late father, "Cárdenas the Great".

All in all, despite these advancements, Solórzano and his allies still had to face much resistance from PRI to enact anything, since the systematic and absolute opposition led by the dinosaurios would remind an American watcher of the attitude of southern Dixiecrats toward civil rights. There were many things that were left to be done: many crooks who should have been jailed long ago were still loose, an electoral reform to finally end fraud (one of the few things that PAN and FDN agreed on) would never be passed by the current Senate, and, last but absolutely not least, the people who masterminded the Mexican Dirty War, especially former president Luís Echeverría, were still free. It was said one of the only three things that Cárdenas could do was pass funding bills to make sure that important pieces of infrastructure didn't break down from lack of maintenance.

The second thing he could do was dedicate a greater amount of time than usual managing Mexico's foreign policy. Speaking of that, the nation was directly benefited by two world events that were completely out of its control. The first and most distant of them was the Rape of Basra, which occurred in 1987, when Iranian troops finally took over Iraq's second largest city after a four-year siege and massacred its population, totally dismantling the very structures of the Iraqi state and throwing it into a civil war from which it is yet to recover (5). This horrific atrocity ensured that oil prices would remain high throughout the late eighties and early nineties, giving the newborn Mexican democracy a critical source of revenue.

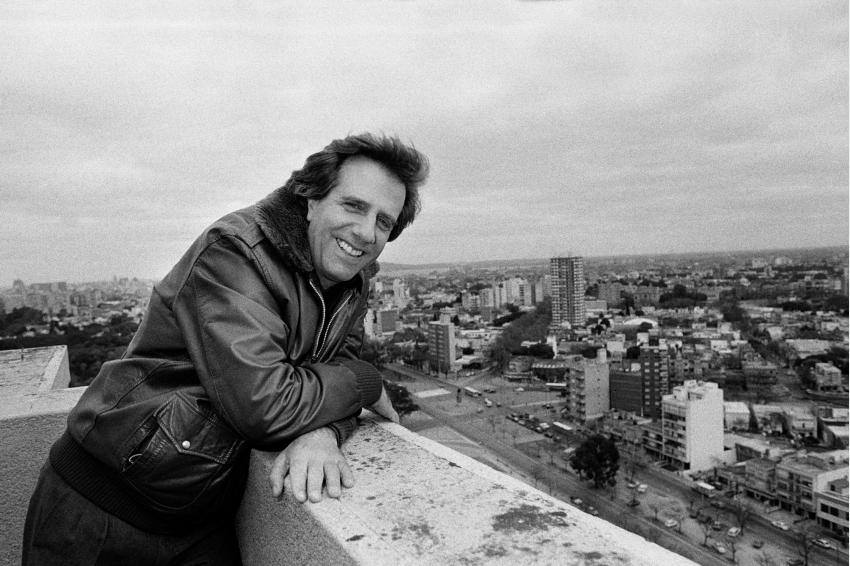

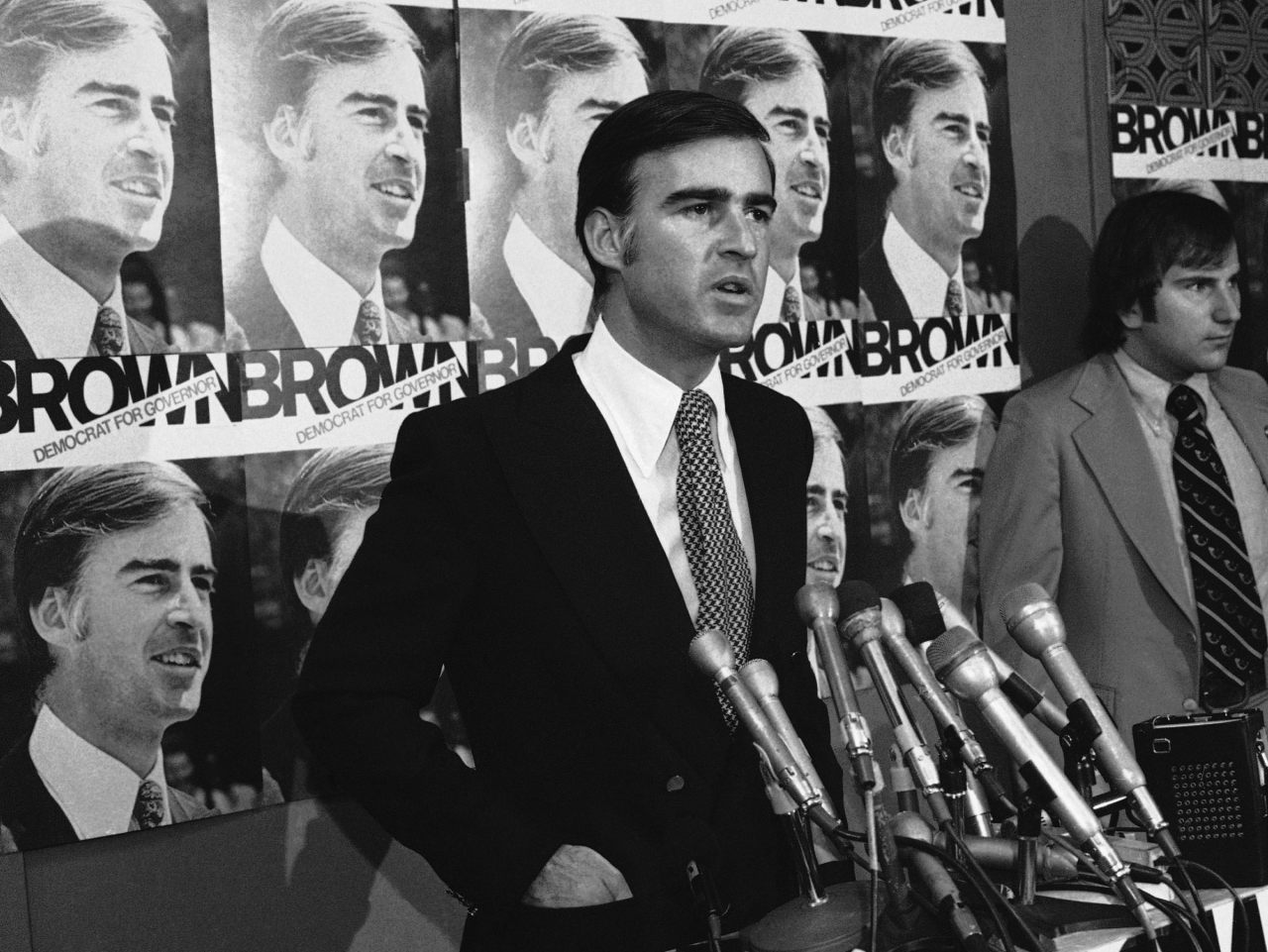

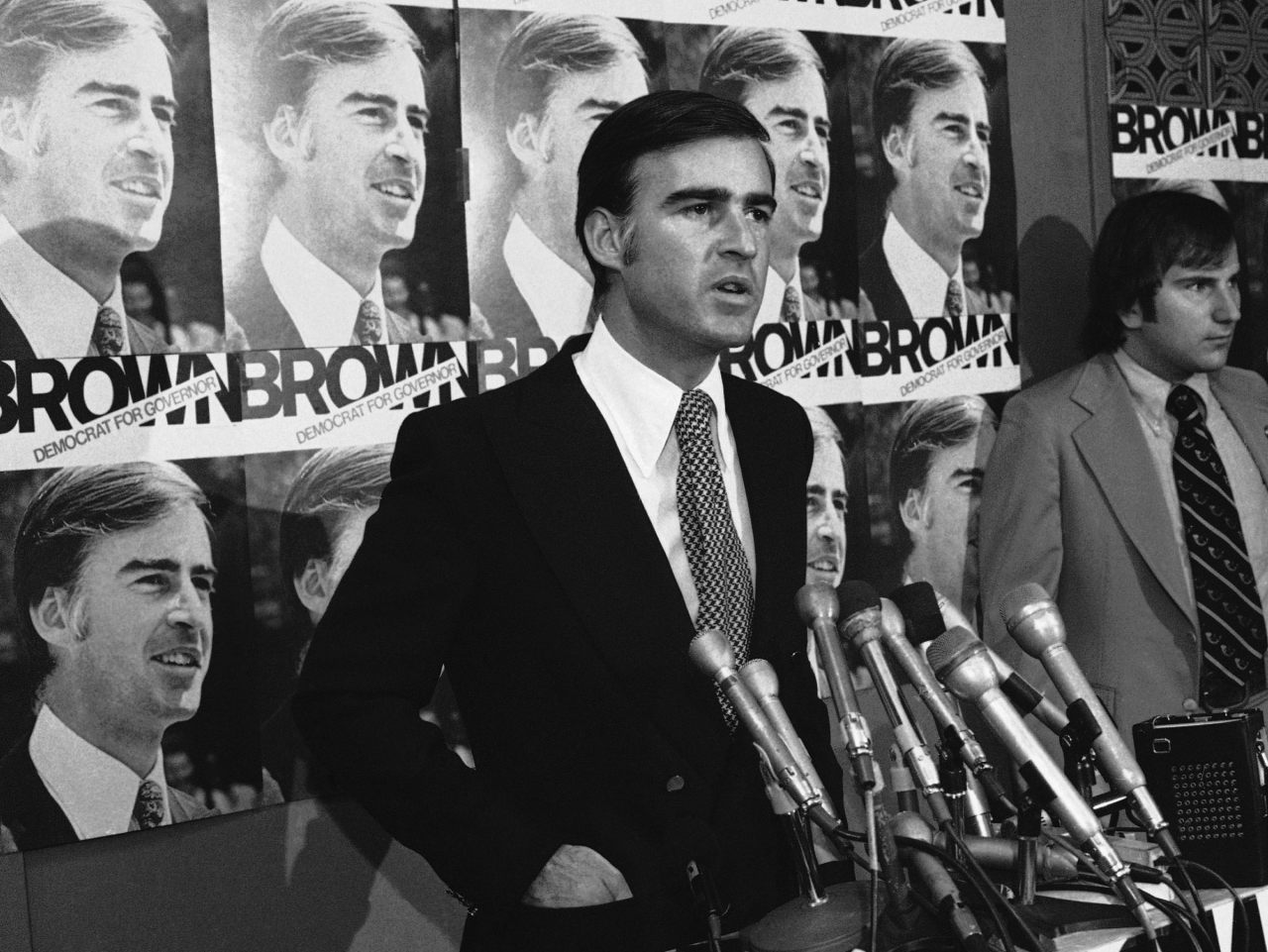

The second and much closer event was the election of California senator Jerry Brown for the presidency of the United States of America. He and his running mate, Pennsylvania governor Allen Ertel (6), were also benefited by the Rape of Basra, since the incumbent Republican president, Ronald Reagan, resigned in disgrace because he and high-ranking members of his administration were involved in a scandal that became known as Irangate. Said scandal consisted of secret arms sales to the Iranian government, with the Reagan administration using the funds acquired from these transactions to support the Contras, a terrorist group in Nicaragua that had lauched itself into a war against the democratically elected government of Daniel Ortega, who first took power in 1979 after unseating dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle in a revolution (7).

Brown was an ardent opponent of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) and immediatly pulled the USA out of the talks focused on its creation, ensuring that it would never materialize. President Cárdenas would no longer have to worry about the possibility of Mexican farmers being outcompeted by American companies within their own country's borders. He was also free to seek closer commercial links with fellow Latin American countries, particularly those that, like Mexico and later Brazil, elected presidents that belonged to the so called "Pink Tide".

The eccentric Edumund Gerald "Jerry" Brown Jr. was one of president Reagan's most vicious critics in the US Senate. After taking power, he immediatly set out on undoing most of his predecessor's measures, such as tax cuts for the rich and a hardline stance against leftist parties and governments in Latin America. Some would later say that he became the Pink Tide's northernmost member.

The third and probably most important thing Solórzano could do was build and strengthen his base. The Frente Democrático Nacional that carried him to victory in 1988 was not an united party, but rather a ragtag coalition between several small leftist parties combined with a group of defectors (the "Democratic Current") from PRI. This group was finally unified under one flag on 1990, with the creation of PRD, the Party of the Democratic Revolution, allowing the allies to from now on now coordinate their actions to ensure maximum political impact. Cárdenas also regularly toured the country and spoke with ordinary people whenever possible, solidifying his image as a popular leader. The most important thing he did on this front, however, was personally overseeing the reconstruction of Mexico City, which, according to him, would rise again "like a phoenix reborn from the ashes"(8).

Cuauhtémoc's future prospects improved significantly after July 2, 1989, when he received what was probably the best news he had heard since his presidential victory last year. That day, an election was held in the little state of Baja California in which the governor's seat was at stake. The victor in that race was the panista Ernesto Ruffo Appel, who was elected by an overwhelming majority of the voters (65%) and became the first non-priísta state governor elected anywhere in Mexico in sixty years. After that stunning victory, many once loyal priístas saw the writing in the wall deserted their party en masse, with the bulk of these defectors going to PAN and the few remaining leftists, such as Francisco Luna Kan, former governor of Yucatán, joining ranks with the president. The dinosaurios now had complete control over PRI's machine, but found it on the verge of completely melting away.

Ernesto Ruffo Appel.

The extremely demanding task of running the country became much easier from now on. Even then, not all was birds and roses: as PRI's power declined, the "Democratic Alliance" between PRD and PAN began to show signs of exhaustion, since the two parties had virtually opposed views on how to run Mexico and their common enemy, the one thing that kept them together, was in a state of irreversible decay. Indeed, although he wouldn't ever dare to admit it publicly, president Cárdenas was extremely frustrated with PRONASOL, the world-acclaimed program that became the public face of his administration. Its implementation was only possible thanks to several concessions that he was forced to give to his rightist allies, namely by in the form of the already mentioned privatizations (even if some of them were really necessary) and cuts on other welfare programs.

The Democratic Alliance was finally disbanded after the climatic congressional and gubernatorial elections that took place in 1991 and 1992. In the legislative ones, PRD elected 278 deputies (an absolute majority) and 16 senators, PAN won 153 and 10 seats respectively, and PRI languished in a very distant third, with only 115 deputies and 4 senators, while the rest of the seats were taken over by members of minor parties. On the gubernatorial front, PAN's performance was significantly better, since they captured six governorships (Guanajuato, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Nuevo León, Durango and Durango) and PRD won two seats (Solórzano's home state of Michoacán and San Luis Potosí) with the remaining states electing priísta governors, the most important of them being Puebla, where the infamous dinosaurio Manuel Bartlett Díaz took over the governorship (9).

With clear majorities in both houses of Congress and governors who wouldn't undermine the enforcement of any meaningful measures, president Cárdenas was at last free to pursue his own projects, and he acted accordingly. Throwing himself into a flurry of activity, presenting bill after bill to the legislature, most of which were approved without too many difficulties, the second half of his six-year term became colloquially known as "El Sexenio de Tres Años" (the three-year sexenio). It was during this period that some of his most celebrated measures were enacted, such as a substantial increase in the aid provided by PRONASOL, the Tierra para Todos program, which consisted of subsidies and low interest loans to small landowners, and an absolutely massive increase of investments towards public education. The thousands of new schools built during this period were called "Cientros de Educación Pública Integral" (Integrated Public Education Centers), best known by the acronym of CEPI, obviously inspired by the Brazilian CIEPs idealized by Darcy Ribeiro and Oscar Niemeyer.

A CEPI somewhere in Chiapas. What? Imitation is the best form of flattery, after all, and Brizola certainly didn't mind.

The government also stepped up on its anti-corruption rhetoric and, among other things, ordered the arrest of priísta insider and union boss Elba Esther Gordillo, leader of the National Teachers Union (the largest of its kind in Latin America) and famous for her extravagant and luxurious lifestyle, on charges of corruption and embezzlement that were almost certainly true (10). Most importantly, president Cárdenas ensured that Congress approved the creation of a National Truth Commission to thoroughly investigate what had truly happened in the Mexican Dirty War that occurred in the 1970s, when the Perfect Dictatorship's autocratic tendencies reached their peak (11).

Hundreds of former police officers, paramilitary members, politicians and bureaucrats were prosecuted, and many of them were jailed on charges of murder and crimes against humanity. The most prominent person to be jailed was former president Luis Echeverría Álvarez, who was directly responsible for the Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968, back when he was the Secretary of the Interior of the late former president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, and the Corpus Christi Massacre of 1971, best known as the Halconazo, when he was already Mexico's supreme executive. His trial was highly televised, and his sentencing was celebrated in public parties all over the country, as the relatives of the hundreds of students that were killed under his orders could finally rest assured that justice was done. Echeverría would spend the rest of his life in a prison cell until his death in 2006 at the age of 84 (12).

Echeverría's official portrait as president, when he was at the zenith of his power.

By the time the 1994 presidential election came up, Cárdenas' popularity among the people had reached immense heights, since the measures and achievements mentioned above led to a direct and drastic improvement in their standard of living. He cemented himself as one of his country's greatest leaders, proved to be a worthy successor to his father and someone to be respected and admired even by his detractors thanks to his honesty. As such, it would be very easy to assume that whoever won his endorsement would have a cakewalk ahead of him or her.

Things are rarely so predictable.

The panistas, rallied behind their candidate, deputy Diego Fernández de Cevallos (their 1988 candidate, Manuel Clouthier, had been elected governor of Sinaloa) were emboldened by their numerous gubernatorial victories and ran an energetic campaign, especially in the wealthy northern states, where they were strongest. In the span of only a few years, PAN had grown from an irrelevant opposition party whose sole purpose was to legitimize the Perfect Dictatorship to a force to be reckoned with, one with a very wide support base. Meanwhile, the sinking priístas selected Francisco Labastida Ochoa, a hardliner and former governor of Sinaloa, as their candidate, and they were determined to not die a quiet death, and were poised to take as much of the vote as they could possibly get, something that would obviously throw the potential results into the air.

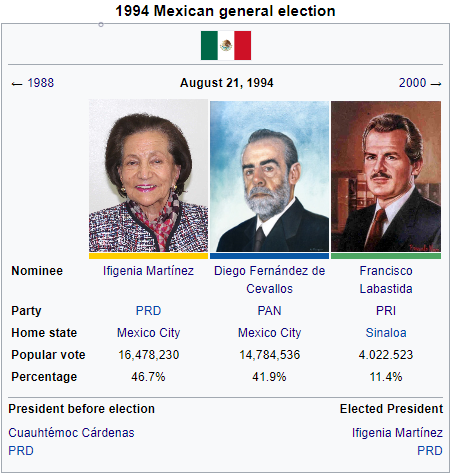

The candidate chosen by PRD, Secretary of Finance Ifigenia Martínez, had her hands quite full, and as a result campaigned with the president all over the country, especially in the south and the capital. She, along with Cevallos and Labastida, also took part in the first presidential debates in Mexican history, which were basically contests between Martínez and Cevallos over who could hit poor Labastida the hardest.

The result of Mexico's first honest election was highly polarized, and although Cárdenas' popularity eventually assured Martínez's victory, Cevallos' herculean effort allowed him to sweep the northern states and come much closer to the presidency than expected. He quickly conceded, content with the fact that PAN was now a powerful force, and extremely glad that PRI was reduced to a battered hollow shell of its once invincible self.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, PRI held an absolute majority in the lower house (260 seats) and a crushing 60 seats in the Senate.

(2) IOTL, Manuel Clouthier was killed in a car accident on October 1989. Here, that doesn't happen.

(3) Salinas de Gortari's first act, on November 1988, was to create PRONASOL, which he used not to assist the poor, but rather to bribe voters and prevent them to vote for opposition candidates. ITTL, since Cárdenas faces a determined opposition from PRI, it is enacted almost three months later, but it will also be more focused toward the needy.

(4) IOTL, Telmex was given to Carlos Slim Helú.

(5) I may or may not write an update about the Iran-Iraq War.

(6) Allen Ertel ran for the governorship of Pennsylvania in 1982, but was narrowly defeated by incumbent GOP governor Dick Thornburgh. Here, he barely wins and becomes senator Brown's running mate.

(7) And look at where Ortega is now.

(8) Title Drop!

(9) This guy is a nasty piece of work. If you want to know more, just take a look at Roberto El Rey's excellent timeline.

(10) IOTL, Gordillo was only arrested in 2013.

(11) As far as I know, Mexico never had anything like a truth commission IOTL.

(12) IOTL, Echeverría was briefly put into house arrest in 2006 over his crimes, but was released on bases of ill health. Now he's 97 years old and will certainly die a free man.

Foreign Snapshot: El Fénix

It is still difficult, to this day, to describe the amount of sheer joy that the people of Mexico felt on December 1, 1988. That day, president Miguel de la Madrid, a member of the hated and seemingly invincible PRI, handed the presidential sash and all of the executive power that belonged to him to his successor, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Solórzano, who had somehow performed the impossible and brought an end to 59 years of single-party rule. The mood of the crowd of at least 500.000 people that gathered in the Zócalo to greet the new ruler of the most populous Spanish speaking country on Earth could only be described as completely delirious. Despite their somehow almost simultaneously stopped cheering to listen to every word he said, as if he was a Messiah who would lead them to an era of endless prosperity. And they certainly weren't the only ones in the nation who believed in that.

It was simply too much of a coincidence for that to not happen. The last time Mexico elected an opposition candidate was in... 1910, when none other than Francisco Madero, a hardworking and honest man who gave his life for his country, brought an end to the Porfiriato, a corrupt dictatorship that lasted for 35 years. As if that wasn't enough, it didn't even take an armed insurrection to get PRI out of power: all they needed to do was organize and vote for the right candidate. It was time for a new Revolution, one that manifested itself through laws and rallies, rather than vast armies and bloody battles.

To add to these wild (at the very least) expectations, the new president was the son of Lázaro Cárdenas, who was probably the best leader that the country had in the 20th century, with any attempt to criticize him being seen as a mortal sin. As such, Cuauhtémoc definitely had the "pedigree" to be an excellent ruler, and that was without the executive experience that he earned during the six years as governor of Michoacán, a state that his father also commanded. And since sons are supposed to be better than their fathers, well...

Poor Solórzano didn't meet his people's expectations. No one could.

After he took over, everyone found out the grim reality that PRI wasn't dead at all: they still had all of Mexico's state and local governments under their control, along with a substantial portion of the Chamber of Deputies that was enough to cause quite a headache, even if they didn't have an absolute majority, and worst of all, they had a crushing majority in the Senate, where they controlled 55 seats, while the FDN held 7 seats and PAN just 2 seats (1). The legislature, which for decades served only to rubber stamp decisions made by autocratic presidents, suddenly armed itself to the teeth and stood ready ready stonewall all of Cárdenas' initiatives and turn his life into a living hell.

How was he supposed to get anything done under these conditions?

It is often said that politics make strange bedfellows, and what Solórzano did on January 5, 1989 proved that. Simmering after being effectively forbidden from doing his work thanks to systematic opposition from PRI hardliners (dinosaurios) in Congress and in the states, the president had a meeting with Manuel Clouthier (2), Diego Fernández de Cevallos and Luis H. Álvarez, the highest-ranking panistas in the country. There was just one hurdle, however: their agenda was almost completely opposed to the one Cárdenas defended. While he and FDN were center-left and strongly secularistic, PAN was closely linked with conservative northern industrialists and catholics who opposed the many restrictions imposed on the Church. On any normal situation, these two groups would despise each other.

In spite of all of that, they agreed on one crucial thing that ensured that their alliance became a reality: they loathed PRI infinitely more than each other.

Left to right: Diego Fernández de Cevallos, Manuel Clouthier, Rosario Ibarra (a former communist and ally of the president), Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Luis H. Álvarez. As one can see, none of them are really happy about the recent turn of events.

Right after that alliance was made, president Cárdenas renewed his efforts to get at least one major piece of legislation through the dinosaurios that dominated the Senate. After weeks of negotiations, backroom deals, arm twisting and some honestly humiliating begging to priístas that he would never forget or forgive, he finally got his wish: on January 21 (3), the federal government announced the creation of the National Solidarity Program (PRONASOL) , an ambitious initiative that would later earn international praise and serve as a model for other Latin American countries to follow, particularly those who elected Pink Tide governments. It consisted of the channeling of federal resources to impoverished areas that were lacking in healthcare, education and basic infrastructure, ensuring that the people who lived in these regions experienced an improvement of their standard of living.

On the other hand, Cárdenas had to honor his end of the pact with PAN, whose assistance was critical in the creation of PRONASOL. To do that, he completed the privatization of Telmex, the state telephone company, which had started under Madrid's administration and concluded with it being sold to media mogul Joaquín Vargas Gómez, owner of the radio broadcaster MVS Comunicaciones (4). The banking industry which was nationalized in the last days of the troubled and corrupt presidency of José López Portillo, who preceded Miguel de la Madrid, was returned to the private sector. On the religious front, the Catholic Church was allowed to hold property once more, and priests were allowed to vote and wear their robes in public.

These measures did much to mitigate the concerns of international investors who, despite approving the downfall of a corrupt government (it's bad for business, after all) still had that kneejerk fear that a left-of-center administration would enact extremist policies regarding the economy. The end of the restrictions on the Church was also well received by the Mexican population in general, which was and still is highly religious, and was also seen as an important step towards the full democratization of the country. However, there were also sectors of the left, mostly radical university students, that were disillusioned with them, believing that the president was shifting himself to the right and abandoning his original projects. Some of them even began to call him "Cárdenas the Little", in contrast with his late father, "Cárdenas the Great".

All in all, despite these advancements, Solórzano and his allies still had to face much resistance from PRI to enact anything, since the systematic and absolute opposition led by the dinosaurios would remind an American watcher of the attitude of southern Dixiecrats toward civil rights. There were many things that were left to be done: many crooks who should have been jailed long ago were still loose, an electoral reform to finally end fraud (one of the few things that PAN and FDN agreed on) would never be passed by the current Senate, and, last but absolutely not least, the people who masterminded the Mexican Dirty War, especially former president Luís Echeverría, were still free. It was said one of the only three things that Cárdenas could do was pass funding bills to make sure that important pieces of infrastructure didn't break down from lack of maintenance.

The second thing he could do was dedicate a greater amount of time than usual managing Mexico's foreign policy. Speaking of that, the nation was directly benefited by two world events that were completely out of its control. The first and most distant of them was the Rape of Basra, which occurred in 1987, when Iranian troops finally took over Iraq's second largest city after a four-year siege and massacred its population, totally dismantling the very structures of the Iraqi state and throwing it into a civil war from which it is yet to recover (5). This horrific atrocity ensured that oil prices would remain high throughout the late eighties and early nineties, giving the newborn Mexican democracy a critical source of revenue.

The second and much closer event was the election of California senator Jerry Brown for the presidency of the United States of America. He and his running mate, Pennsylvania governor Allen Ertel (6), were also benefited by the Rape of Basra, since the incumbent Republican president, Ronald Reagan, resigned in disgrace because he and high-ranking members of his administration were involved in a scandal that became known as Irangate. Said scandal consisted of secret arms sales to the Iranian government, with the Reagan administration using the funds acquired from these transactions to support the Contras, a terrorist group in Nicaragua that had lauched itself into a war against the democratically elected government of Daniel Ortega, who first took power in 1979 after unseating dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle in a revolution (7).

Brown was an ardent opponent of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) and immediatly pulled the USA out of the talks focused on its creation, ensuring that it would never materialize. President Cárdenas would no longer have to worry about the possibility of Mexican farmers being outcompeted by American companies within their own country's borders. He was also free to seek closer commercial links with fellow Latin American countries, particularly those that, like Mexico and later Brazil, elected presidents that belonged to the so called "Pink Tide".

The eccentric Edumund Gerald "Jerry" Brown Jr. was one of president Reagan's most vicious critics in the US Senate. After taking power, he immediatly set out on undoing most of his predecessor's measures, such as tax cuts for the rich and a hardline stance against leftist parties and governments in Latin America. Some would later say that he became the Pink Tide's northernmost member.

The third and probably most important thing Solórzano could do was build and strengthen his base. The Frente Democrático Nacional that carried him to victory in 1988 was not an united party, but rather a ragtag coalition between several small leftist parties combined with a group of defectors (the "Democratic Current") from PRI. This group was finally unified under one flag on 1990, with the creation of PRD, the Party of the Democratic Revolution, allowing the allies to from now on now coordinate their actions to ensure maximum political impact. Cárdenas also regularly toured the country and spoke with ordinary people whenever possible, solidifying his image as a popular leader. The most important thing he did on this front, however, was personally overseeing the reconstruction of Mexico City, which, according to him, would rise again "like a phoenix reborn from the ashes"(8).

Cuauhtémoc's future prospects improved significantly after July 2, 1989, when he received what was probably the best news he had heard since his presidential victory last year. That day, an election was held in the little state of Baja California in which the governor's seat was at stake. The victor in that race was the panista Ernesto Ruffo Appel, who was elected by an overwhelming majority of the voters (65%) and became the first non-priísta state governor elected anywhere in Mexico in sixty years. After that stunning victory, many once loyal priístas saw the writing in the wall deserted their party en masse, with the bulk of these defectors going to PAN and the few remaining leftists, such as Francisco Luna Kan, former governor of Yucatán, joining ranks with the president. The dinosaurios now had complete control over PRI's machine, but found it on the verge of completely melting away.

Ernesto Ruffo Appel.

The extremely demanding task of running the country became much easier from now on. Even then, not all was birds and roses: as PRI's power declined, the "Democratic Alliance" between PRD and PAN began to show signs of exhaustion, since the two parties had virtually opposed views on how to run Mexico and their common enemy, the one thing that kept them together, was in a state of irreversible decay. Indeed, although he wouldn't ever dare to admit it publicly, president Cárdenas was extremely frustrated with PRONASOL, the world-acclaimed program that became the public face of his administration. Its implementation was only possible thanks to several concessions that he was forced to give to his rightist allies, namely by in the form of the already mentioned privatizations (even if some of them were really necessary) and cuts on other welfare programs.

The Democratic Alliance was finally disbanded after the climatic congressional and gubernatorial elections that took place in 1991 and 1992. In the legislative ones, PRD elected 278 deputies (an absolute majority) and 16 senators, PAN won 153 and 10 seats respectively, and PRI languished in a very distant third, with only 115 deputies and 4 senators, while the rest of the seats were taken over by members of minor parties. On the gubernatorial front, PAN's performance was significantly better, since they captured six governorships (Guanajuato, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Nuevo León, Durango and Durango) and PRD won two seats (Solórzano's home state of Michoacán and San Luis Potosí) with the remaining states electing priísta governors, the most important of them being Puebla, where the infamous dinosaurio Manuel Bartlett Díaz took over the governorship (9).

With clear majorities in both houses of Congress and governors who wouldn't undermine the enforcement of any meaningful measures, president Cárdenas was at last free to pursue his own projects, and he acted accordingly. Throwing himself into a flurry of activity, presenting bill after bill to the legislature, most of which were approved without too many difficulties, the second half of his six-year term became colloquially known as "El Sexenio de Tres Años" (the three-year sexenio). It was during this period that some of his most celebrated measures were enacted, such as a substantial increase in the aid provided by PRONASOL, the Tierra para Todos program, which consisted of subsidies and low interest loans to small landowners, and an absolutely massive increase of investments towards public education. The thousands of new schools built during this period were called "Cientros de Educación Pública Integral" (Integrated Public Education Centers), best known by the acronym of CEPI, obviously inspired by the Brazilian CIEPs idealized by Darcy Ribeiro and Oscar Niemeyer.

A CEPI somewhere in Chiapas. What? Imitation is the best form of flattery, after all, and Brizola certainly didn't mind.

The government also stepped up on its anti-corruption rhetoric and, among other things, ordered the arrest of priísta insider and union boss Elba Esther Gordillo, leader of the National Teachers Union (the largest of its kind in Latin America) and famous for her extravagant and luxurious lifestyle, on charges of corruption and embezzlement that were almost certainly true (10). Most importantly, president Cárdenas ensured that Congress approved the creation of a National Truth Commission to thoroughly investigate what had truly happened in the Mexican Dirty War that occurred in the 1970s, when the Perfect Dictatorship's autocratic tendencies reached their peak (11).

Hundreds of former police officers, paramilitary members, politicians and bureaucrats were prosecuted, and many of them were jailed on charges of murder and crimes against humanity. The most prominent person to be jailed was former president Luis Echeverría Álvarez, who was directly responsible for the Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968, back when he was the Secretary of the Interior of the late former president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, and the Corpus Christi Massacre of 1971, best known as the Halconazo, when he was already Mexico's supreme executive. His trial was highly televised, and his sentencing was celebrated in public parties all over the country, as the relatives of the hundreds of students that were killed under his orders could finally rest assured that justice was done. Echeverría would spend the rest of his life in a prison cell until his death in 2006 at the age of 84 (12).

Echeverría's official portrait as president, when he was at the zenith of his power.

By the time the 1994 presidential election came up, Cárdenas' popularity among the people had reached immense heights, since the measures and achievements mentioned above led to a direct and drastic improvement in their standard of living. He cemented himself as one of his country's greatest leaders, proved to be a worthy successor to his father and someone to be respected and admired even by his detractors thanks to his honesty. As such, it would be very easy to assume that whoever won his endorsement would have a cakewalk ahead of him or her.

Things are rarely so predictable.

The panistas, rallied behind their candidate, deputy Diego Fernández de Cevallos (their 1988 candidate, Manuel Clouthier, had been elected governor of Sinaloa) were emboldened by their numerous gubernatorial victories and ran an energetic campaign, especially in the wealthy northern states, where they were strongest. In the span of only a few years, PAN had grown from an irrelevant opposition party whose sole purpose was to legitimize the Perfect Dictatorship to a force to be reckoned with, one with a very wide support base. Meanwhile, the sinking priístas selected Francisco Labastida Ochoa, a hardliner and former governor of Sinaloa, as their candidate, and they were determined to not die a quiet death, and were poised to take as much of the vote as they could possibly get, something that would obviously throw the potential results into the air.

The candidate chosen by PRD, Secretary of Finance Ifigenia Martínez, had her hands quite full, and as a result campaigned with the president all over the country, especially in the south and the capital. She, along with Cevallos and Labastida, also took part in the first presidential debates in Mexican history, which were basically contests between Martínez and Cevallos over who could hit poor Labastida the hardest.

The result of Mexico's first honest election was highly polarized, and although Cárdenas' popularity eventually assured Martínez's victory, Cevallos' herculean effort allowed him to sweep the northern states and come much closer to the presidency than expected. He quickly conceded, content with the fact that PAN was now a powerful force, and extremely glad that PRI was reduced to a battered hollow shell of its once invincible self.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, PRI held an absolute majority in the lower house (260 seats) and a crushing 60 seats in the Senate.

(2) IOTL, Manuel Clouthier was killed in a car accident on October 1989. Here, that doesn't happen.

(3) Salinas de Gortari's first act, on November 1988, was to create PRONASOL, which he used not to assist the poor, but rather to bribe voters and prevent them to vote for opposition candidates. ITTL, since Cárdenas faces a determined opposition from PRI, it is enacted almost three months later, but it will also be more focused toward the needy.

(4) IOTL, Telmex was given to Carlos Slim Helú.

(5) I may or may not write an update about the Iran-Iraq War.

(6) Allen Ertel ran for the governorship of Pennsylvania in 1982, but was narrowly defeated by incumbent GOP governor Dick Thornburgh. Here, he barely wins and becomes senator Brown's running mate.

(7) And look at where Ortega is now.

(8) Title Drop!

(9) This guy is a nasty piece of work. If you want to know more, just take a look at Roberto El Rey's excellent timeline.

(10) IOTL, Gordillo was only arrested in 2013.

(11) As far as I know, Mexico never had anything like a truth commission IOTL.

(12) IOTL, Echeverría was briefly put into house arrest in 2006 over his crimes, but was released on bases of ill health. Now he's 97 years old and will certainly die a free man.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/10172515/565c2c88a886e.jpg)