History of Mughal Expansion Northwards

Excerpt from "The Mongol Inheritance" by Marissa di Castello

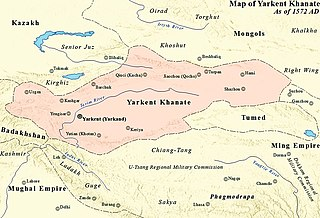

Mughal relations with the Yarkand Khanate had begun much earlier than the reign of Jahanzeb Shah and arguably when the Mughals moved into India, they never really lost touch with their Moghul cousins. Thus there was a constant economic exchange, an exchange of sufi saints and religious thought and even exchange of nobles- when the Barlas clan fell out of favour in the Tarim basin they found an honoured place in the court of Jahangir. In fact, while the first two generations of Mughals were truly Moghuls in India with Babur’s conquests making India an integral part of the wider Chagataid realms, the reign of Akbar represents a slight cooling of relations, where the Khans of Yarkand become younger siblings of the Badshah of Hindustan in a political sense rather than an actual tie of kinship. By the 17th century, while by no means as alien as the Chinese, the Mughals seemed rather more different to the Moghuls than the Khans of Bukhara, as the Mughals became creatures of Hindustan. Nevertheless the choice of Yarkand as capital indicates how strong the southwards pull of the Mughals was to Moghul political culture. The Mughals also dominated the international trade of the tarim basin, as evidenced by the decision of the Yarkand Khans to imitate Mughal coinage, a currency that people trusted more than Ming or early Qing coins. In 1603, we know that a caravan of 500 merchants made annual journey from Kabul to Kashgar, along the same route that Buddhism spread to China centuries ago, but at that point the journey was dangerous and losses were frequent. Bernier calls it a well established fact that caravans from China go through the Tarim Basin to reach India annually and the efficiency of communication between the Mughal and Moghul worlds is evidenced by the fact that merchants from Kashgar were aware of the route that Aurangzeb would take in order to link up with the moving target of the imperial camp in Kashmir which suggests a regularity of trade and travel that goes beyond the annual caravan of earlier accounts. After a century of relative absence from court chronicles, from Aurangzeb’s reign steady flows of embassies between Moghul and Mughal are reported. Although for the 17th century, India mainly features in Tarim chronicles as a place of exile, as those who fell out of favour in Tarim found themselves showered with gifts and honour in India.

In 1700, the Mughals made a token attempt to restore Chagataid rule in the embattled Yarkand Khanate by sending an heir of Yolbars Khan with military aid just prior to its conquest by the Dzungars forced the last Yarkand Khan to flee to Delhi, although its fate never entered the chronicles, presumably due to its quick failure. A court in exile established itself in India hoping to gain support for a muslim reconquest of the Tarim basin and so we turn to the Mughal relations with the Dzungar Khanate.

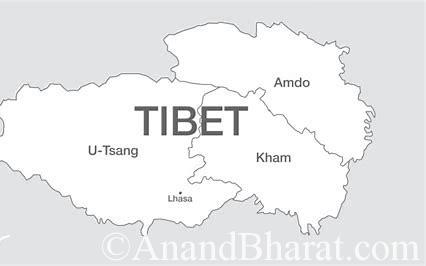

In 1684, the Dzungar-Tibet-Mughal-Ladakh war had involved imperial forces in the dispute between Tibet and Ladakh and despite this, they lost due to the majority of their forces being tied up in pacifying and conquering peninsular India and the difficulty in conducting a traditional war in the mountainous terrain of the Himalayas. Nevertheless, it was an opportunity for the Mughal court to become acquainted with the new power in the steppe and the first embassy to the Dzungar court was in 1692- at this point, the Mughal-Tibet war secured Ladakh its religious freedom, with the Mughal emperor designated the protector of the right of Bhutan, Ladakh and Nepal to continue patronage of the Drukpa school, as opposed to the Gelugpa of the Tibeto-Oirat aristocracy and regulated a trade agreement between the two powers. This original Mughal favouring of the Drukpa school was a result of the arrival of Drukpa emissaries at the court of Aurangzeb, who was of course disgusted by the schools denial of any foundationally important godhead but at the same time impressed by the manner in which Drukpa monks were much more focused on personal growth and meditation, living lives as simplistic and renunciatory as any fakir. Nevertheless, Tibetan suzerainty of Guge and Phurang were confirmed and the presence of Drukpa ascetics and teachers was decimated within the following decades.

The Dzungar Khanate was also now desperate for allies, following the alliance of Khalkha and Qing and while initial negotiations went well, they broke down once the Dzungars realised the price for Mughal aid would be the return of the Yarkand Khanate’s independence. Still, Tsewang Rabtan was impressed by the quality and size of the tents and presents he had been given by Aurangzeb and sent an envoy to Kashmir to see the Mughal court, and this was the moment that Mughal awareness of Buddhism exploded and the beginning of regular missions to Tibet, where Sanskrit texts were copied out and printing began in the 1710’s. The 5th Panchen Lama visited Jahangirabad-Dhaka in 1697 and was received with full splendour by the Subahdar of Bengal.

In 1706, the 6th Dalai Lama, after living a life of hedonism and pleasure received word that the Khoshut Khan and the Qing emperor were conspiring to kill him and escaped to India in a dramatic flight, after which he escaped to Kashmir through Yarkand and from there to Delhi, where he became an opium addict famous for his poetry throughout the Persianate world, with the pen name Darya. While he was alive, a new Dalai Lama could not be named, and thus the Khoshut Khanate, the Qing empire and the Dzungar empire made repeated overtures for the Lama to be returned so that he could be covertly executed however Azam Shah was much pleased by his poetry and sent envoys to the Kangxi Emperor telling him that the Lama was under his protection, and that he needed to stop sending assassins. Upon special orders from the Kangxi Emperor, T’o Shih performed a full kowtow to Azam Shah- a signal that in the Qing diplomatic system, India already held a position implicitly equal to China, or at least equal to Russia. In return, the envoys to Beijing made every effort to conform to Chinese court ceremonial, both performing the kowtow and the Kurnish and Taslim.

This was the first direct contact between the Qing court of Beijing and the Mughal court of Delhi. In his letter, Azam Shah frames himself in primarily Turco-Mongol terms, naming himself as the descendant of Genghis Khan through Chagatai, the Just Khagan, the Caliph of Islam, and lastly the Badshah-e Hind. This is the first instance we see of the new design of the Sacred Seal of the Mughals- the previous design was modelled on the solar system, with the current emperor’s name in the middle, representing the sun, with circles containing the names of his ancestors up to Timur on the border. Directly above him was the name of Timur, and at eleven o clock was the name of his immediate predecessor, with each name apart from Timur preceded by an “ibn”. In the new design, while the current emperor is still representative of the sun in the middle, and the inner circle still traces the line back to Timur, at Babur’s circle the line branches into an outer circle which traces his descent from Genghis Khan, such that Genghis Khan is directly opposite to Timur at 6 o’ clock, the metaphorical base of the dynasty. The claim to the title of Khagan was not taken particularly well by the Manchu leadership, whose own dominance of the Khalkha mongols was only 14 years old- however, the extremely extravagant caravan of gifts given by the Mughal court was seen as tribute by the Han bureaucracy and the Manchus portrayed this as them having forced the rulers of India to submit to them.

In 1719, the 6th Dalai Lama died in mysterious circumstances, either because of an opium overdose or because he was poisoned (the Mughal family believed until at least 1736 that poison could be detected through the use of jade utensils, so on this occasion perhaps using jade utensils made them lax in security).

Meanwhile in Tibet, Lhazang Khan used the power of the Mughal throne to stop Tibet becoming a protectorate of the Qing, who wanted control of Lhasa to control the Tibetan Buddhist Mongols- this was a much less taxing demand than the Mughals made, which was to aid in the re-establishment of Chagatayid rule in Moghulistan. To this end he sought to strengthen ties with the Mughal nobility, sent his daughter to marry Azam Shah in 1710 and increased the patronisation of Sanskrit literature in Tibet by making it a requirement for all monasteries to teach Sanskrit and Persian so that regular missions could be sent to bring the people of India to Buddhism, as well as spreading the authority of the Gelug church throughout the Persianate world and beyond. However, relations cooled in 1715 when he led an invasion of Bhutan, which was seen by the Mughals as a vassal state and so in the Mughal-Tibet war of 1715, when Lhazang Khan quickly surrendered and Mughal troops marched into Lhasa. Tibet was forcibly opened up to Muslim missionary activity and a major Shiva temple was built by Raja Jai Singh Kachwaha modelled on Pashupatinath in Kathmandu on the banks of lake Mansarovar- thus it commanded a full view of Mt. Kailash, the sacred home of Shiva in Hinduism. An agreement was reached whereby Mughal mansabdars could pay the Lhasa government an annual lease for the use of the famous gold fields in the territory annexed from Ladakh last century. Furthermore, the Tibetans agreed to help the Mughals reconquer the Tarim Basin, whenever the Mughals asked them to. Apart from this, no reprisals were taken, there were no territorial adjustments and the people of Tibet were impressed by the discipline and general civility of the Mughal army. In 1726, the Khoshut Army was joined by 30,000 Mughal troops and they invaded the Tarim Basin, with Sanjeev Khan, the son of the Torgut Ayushi Khan (previously an agent of the Russian tsar) acting as a commander as he had fled to India after betraying his father to the Dzungars in 1701 and then risen up the ranks in the Mughal military- he now had a promise that if the Dzungar Khanate was conquered, he would become the Nawab of Moghulistan (the Yarkand Chagataids had by this point grown to prefer the security and comforts of India, and were already acting as Subahdars of Malwa at the time). The Dzungars under Tsewang Rabtan were unprepared for the two pronged attack from across the Karakorum and through Tibet and were quickly pushed out of the Tarim Basin.

The Dzungars meanwhile had been gradually falling into the Indian cultural orbit, a process which had begun in the 1690’s. From that time they had been active participants in the threeway trade between Russia, India and China and with commercial partnerships came intellectual partnerships as the Dzungar clergy attempted to convert the masses of India and Tsewang Rabtan sent his own family to argue the case for Buddhism in the Ibaadat Khana’s of India, accompanied by the great influx of Sanskrit texts from Tibet into India in the 1710-30’s. Galdan Cering was fluent in Persian and Braj Bhasha, had himself toured India in his youth, ended the religious based taxes in the Khanate and had founded monasteries in Lahore, Kabul and Delhi. Unlike the torguts however, there was no way for them to directly invest in and profit from seaborne trade, as that was dependent on the safe transport of goods and money in a system that was difficult to enter from outside the Mughal system. Nevertheless, they were enthusiastic about the opportunities they were allowed to have, and some Choros mongols took the opportunity to take the voyage to the Americas, where their career had momentous results.

As well as his cultural refinement, Galdan Cering was an able ruler. He carried out many successful raids against the Kazakhs, in Ferghana and in Bukhara, and much of the Mughal mobilisation prior to the campaigns in Bukhara was explained by the need to defend Kabul from his forces. He was unsuccessful in his attempts at breaching the Hindu Kush (whether his invasion was a real invasion or a successful attempt to get the Mughal government to pay him to go away and equip his armies with guns is debated) , and was further unable to establish any authority amongst the Khalkha mongols, as they were protected by the Qing. His forces weakened Bukhara and eroded trust in its government such that the Bukharan emirs were much more willing to switch allegiances to the Kokhandi Khans and submit to the Mughal protectorate. By this time, the Dzungar armies comprised 90,000 standing cavalry equipped with firearms.

The Mughal court sent two grand embassies to the Qing under Jahanzeb Shah on the accession of the Yongzheng and Qianlong Emperors, with eight more minor embassies and permanent ambassadors posted in Beijing as well. The embassies were meant to strike the imagination of the Chinese, impress the newly crowned emperors, and convince them of the warmth that Jahanzeb Shah had for them. Each grand embassy came with a thousand servants, 500 painters and famous writers. The second embassy had 10 elephants, 60 antelopes, 34 European hunting dogs, 100 pure white horses, and 10,000 precious articles of gold, silver, jade and ivory, much of which was used in the decoration of the Gardens of Perfect Brightness in Beijing.

The new subah of Eastern Moghulistan was in a precarious position however, as the Dzungars remained a powerful threat to the northwest, as was the Khanate of Kokand, not to mention the growing Qing interest in the region. The Qing court had previously sent a demand for the Mughal garrison in Lhasa to leave immediately following the Mughal-Tibet war, and a treaty had been signed at Lhasa in 1716 that said Mughal troops were not to enter U-Tsang as long as Qing troops didn’t. The other two regions of Tibet, Amdo and Kham were given over to the Qing government. Meanwhile the Qing had annexed and renamed Qinghai, much to the distress of the Khoshut Leadership, who appealed to the Subah court at Yarkand for help which was denied as Jahanzeb Shah had ordered that no Mughal troops were to go east of the Tarim Basin, as a full scale war with the Manchu empire looked unprofitable. Of course, reasons for investing so heavily into the Tarim basin were not purely dynastic- it had been the only source of jade for the empire since Jahangir and Moghulistan society was soon being transformed by the influx of Rajasthani mining castes, trained in the most modern European methods of mining by their Mansabdar employers, in order to increase the output of the jade mines of Kashgar.

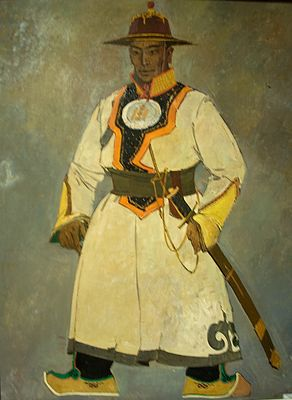

Further, any reinforcements would have to come from across the Karakorum and so the garrison at Kashgar knew it would have to hold out a long time before help arrived. Sanjeev Khan as his first task as Nawab attempted to intervene in the Dzungar succession crisis after the death of Tsewang Rabtan and managed to draw the Torguts under Mughal leadership in 1726, with their leadership being granted audience with Jahanzeb Shah in Kabul where he honoured them with Mughal titles such as Khan-I Khanan and Khan Jahan, as well as Sanskrit titles owing to the importance of Sanskrit for the Buddhist torguts such as Dharmapala Khan and Jagat Khan. With the establishment of Mughal protectorate over western Moghulistan in 1742, the years of Dzungar raiding and border skirmishes finally ended as the four Dzungar

tribes, having seen both the wealth and prestige the torguts had accumulated through the transit trade between India and China, as well as the penetrative power of the Mughal military in their own central Asian homeland in small bands started defecting to become Mughal auxiliaries. At the death of Galdan Cering in 1742, a period of bloody civil war ensued between his sons, and in 1744 the Khoyid Chief Amursana took control of the Four. Internal strife continued until the Dorbets in their entirety went over to the Mughals, with the son of Galdan Cering’s second cousin, Davaji going to the Qing. The Qianlong emperor wasted no time sending a joint Manchu-Mongol force of 50,000 across the western road, while Mirza Kabir, the soon to be Prithvi Narayan Shah personally led his force of 40,000 plus the 20,000 Dorbet and 20,000 Torghut from Samarqand to Ili, in the event that the Qing were willing to fight for control of the Dzungars. To maintain the unity of the Four Oirat, the Dzungar and Khoyid nobility submitted to federation with the Mughal state. In the Mughal-Oirat Code of 1746, the rights and responsibilities of the members of each of the Four Oirat, the Khanate of Kokhand and the Mughal State are enumerated, in a parallel to the Oirat-Mongol Great Code a century earlier. The code (cayaga) was written in Sanskrit, Mongolian, Chagatai and Persian, but certain terms which didn’t have exact equivalents in a certain language were defined before a loan-word was used from an appropriate language.

The preamble considered the common history of the states involved and their commitment to certain values- chief among these was “tarbiyat” or the potential for training to improve the quality of any man or woman more than good breeding. The Mughal state had been founded on this principle, owing to Babur’s dynastic illegitimacy among the amirs who came to India, and so had the Oirat state, owing to their non-Chingissid status. Importantly, while in some ways the Mughal-Oirat union was a union into a single larger state, it was a headless state with a collective executive made up of the hereditary leaders of the three states.

The first article in the code forces all signatories into collective action against any who destroys the Union (Toro was the Mongolian term used here, normally used for the government and it was noted how the Manchus had seized the toro of the White Jurchen, then the Forty Mongols and then the Chinese Empire). The cayaga enshrines the right of each of the constituents to maintain their own laws and submits disputes to a leader elected by all the signatory parties on a ten year basis. The Great Code created a universal legal framework that regulated the territorial authority of units of administration stretching from the borders of Siberia down to the islands of Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile, the Qing army that had arrived received instructions that it was not to engage with the Mughal forces, and the border was set between the Manchu and Mughal territories between the Altai and Tian Shan mountain ranges, with the Qing receiving the city of Hami, while the Mughal received the city of Turfan.

Prithvi Narayan Shah now personally directed the investment of millions of rupees into the road and sarai network of the area, viewing it as a matter of both economic and strategic importance, and hundreds of thousands of labourers were employed at any one time from 1750 to 1770 in the very centre of asia to improve the connectivity of these lands to the heartlands of Panjab.

Since the Qing campaigns to establish Qinghai, the Khoshut Khanate had attempted to reclaim this ancestral territory through raids and campaigns that severely weakened Qing control over the area and yet they could always just retreat to U-Tsang, where the Qing could not follow them as per the Treaty of Lhasa. Further, the Khoshuts made extensive use of Indian mercenaries, who were trained in a number of different styles, and yet the Qing appeals to the Mughals did nothing as the mercenaries weren’t directly acting on Mughal instruction (though of course all mercenaries were encouraged to display their talents away from India)

In response to this and the Mughal union with the Four Oirat, and citing as well the cultural and moral decay of Tibet under Khoshut rule, the Qianlong emperor invaded U-Tsang in 1756, reaching Lhasa in the May of that year. In this, he was aided by the Lamaist government under the Dalai Lama and Gyurme Yeshe Tseten, which was chafing under the rule of the Khoshut Khans. This was utterly vexing to Prithvi Narayan Shah, as Lhasa was a stones throw from Bihar, and if the Qing controlled the Himalayas there could be no telling when they would descend from the mountains. Originally however, he merely ordered the creation of mountain fortresses created in the Maratha style to guard the passes in the Himalayas that allowed easy transport of large forces and allowed Qianlong to roll into Tibet- he knew the size of the Qing army from his brothers reports and he was unwilling to start another, expensive war for little gain.

Nevertheless, he sent an envoy bedecked with silks, muslins and calicoes to Qianlong, congratulating him on his acquisition of U-Tsang. He hoped that Qianlong would continue to allow the trade and free movement of people and books between Nepal and Tibet as it was continuing and asked him to convey his best wishes to his brother. He ended the letter on a less positive note, informing Qianlong that the Khoshut leadership and Gyurme Namgyal (Darya Bahadur), the brother of the new prince of Tibet, Gyurme Yeshe Tseten had taken refuge in the court of the Refuge of the World (Alampanah), and that the Chagatai Khanate, and anything south of the Himalayas was under the protection of the world seizing emperor, Prithvi Narayan Shah, Khagan of the Oirat, Badshah of Hind.

Further, the Summer Palace in Beijing features a complex known as the Indian Palaces of 1747- a hybrid of the Blessed Fort of Delhi and Dara Shikoh’s palace in Agra, interpreted through the lens of Qing architecture. Its gardens, however, remain wholly Chinese in design and execution and the overall effect is breathtaking.

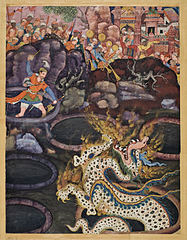

Likewise, Mughal art of both the Nyaya and Dharmic varieties experienced a wave of appreciation for Chinese and Tibetan art corresponding to the chinoiserie craze in Europe at the time. Prior to this, Chinese art had been appreciated in the Mughal ateliers primarily in the Akbar Era, remnants of the influence they had had on post-Mongol Persian art. Many elements of Chinese art had been used as common motifs- for example depictions of dragons in India are largely on the Chinese model. The significance of the motif is completely different in the two contexts, with 16th century Mughal works seeing the dragon as the frightening side of nature as opposed to the Chinese conception of it as a symbol of royal authority and spiritual strength. 18th century Mughal painters, more acquainted with the intended symbolism of the dragon, use it in two senses. On the one hand it is used as a purely decorative element in frescoes, stuccoes and other ornamental arts with no symbolism at all. On the other hand, elements of the Chinese dragon were added onto the concept of the Naga of Indian mythos and the new creature adopted as a symbol of imperial authority, especially in Nyaya areas. Dharmic texts tend to prefer Japanese art.