The Continental Military Machine

Essentially, the difference in the outcome of Shah Jahan’s central Asian campaigns and those of Jahanzeb Shah was the logistical evolution that had since happened. In the earlier exchange, a force of 60,000 had to be withdrawn owing to the difficulty in buying enough local food to support the army and the difficulty in transporting food with them. In the hundred years since however, the commercial traffic between Russia and India had deepened sufficiently that significant portions of the grain needed could be transported through the regular banjara trains. However, the force sent by Jahanzeb Shah was still smaller than that of his predecessor and this decision was made because it was trusted by the Mughal government that they would be able to win without the extra numbers.

The Mughal army had been revolutionised in this hundred year gap, and was in all respects a deadly beast. After the violent birthing pains of Akbar’s era, when the military hit its first peak, the state was large enough to overawe or diplomatically cow the vast majority of its rivals. As a result, it suffered from lack of existential threats and need to innovate, and during the middle of the 17th century, India was noted to be worse in artillery than its Safavid rivals in Iran. This was unacceptable to the domineering spirit of Aurangzeb and he and Shivaji began a period of renovating the military for the modern era, with sufficient diversity in modes of operation that it could function well in all climates and terrains.

After this initial burst of reform, there was another period under Azam Shah during the Deccan Rebellion where the Mughals first began to experiment with European infantry tactics, safe in the knowledge that the rebels had no real cavalry that would make such formations suicidal owing to the monopoly on trade with the horsebreeding regions of Asia that the Mughal state possessed. In this role were primarily Rajput regiments, chosen by the European advisors possibly for the simple reason that they already possessed a uniform and distinguishing colour- in this case, orange. According to those well-versed in ancien regime warfare, a uniform was an indispensable part and parcel of a successful army as it made them feel like part of a cohesive unit. These infantry groups remained a clear minority in most Imperial field armies however, as they could only be used in areas where for whatever reason, be it dense forest coverage or unsuitable terrain for horses, camels or elephants, the volume of projectiles in the air was less than it normally was. In most cases, camel guns, rockets, musketeers, field artillery and horse archers produced a battlefield saturated with fire and forced infantry to fight from behind cover or in open order- lines of infantry would have been suicidal. Nevertheless, contingents and mercenary groups specialising in European tactics were invaluable in the conquest of the trans-pamir mountain states of Balkh and Badakhshan, the island subahs where cavalry was hard to bring and later as Indian armies ranged across the globe.

Mercenaries

As is well known, early modern India had a glut of soldiers- Abu Fazl estimated the population with military training as 4 million at the turn of the 17th century within Hindustan, and by this point there were over 7 million such men within the empires larger borders. While the Mughal state was by far the largest employer of these, keeping a standing army of 500,000 (a decline from the Akbar era feudalistic armies owing to the lack of real need for large armies now that subcontinental sovereignty had been assumed), that still leaves the other five sixths. While significant sections of these were primarily engaged in other trades especially farming, only entering mercenary groups during the months of October to may, the remainder formed a problem for the central administration. These men formed mercenary bands that could potentially severely hinder the workings of the state, however any attempt to forcibly disband them would cause the rest to turn on the Mughal state, depriving the empire of productive citizens and reducing the peoples trust in the government.

The decline of the Delhi sultanate had left India a society where both communities like towns and villages, and institutions like religious orders, guilds and merchant houses were forced to assemble bands of men to protect themselves. In many communities, military service was an essential stage of life. It was more than just a lucrative career- it was a way for individuals and families to permanently change their stations; soldiers often assumed the caste, clan or ethnic identities of their leaders and comrades, learning their languages, traditions and folklore.

They were also very useful for mansabdars who could afford to hire them to protect their goods, especially in the overland trade to China and Russia.Further, by the 1720’s an issue that had been percolating through the minds of the Indian political classes had been solved by the mercenaries- since the conquest of the Deccan sultanates, the military elite of India was very aware that there was no independent power that could threaten the Mughal state. They looked back to the last days of the Lodi dynasty where a tyrant was overthrown when Indian nobles called for the intervention of a foreign power, and knew nothing like that could happen now. Before Alamgir’s military reforms when each mansabdar was responsible for the personal upkeep of a given number of cavalry and infantry, their individual command of troops allowed them to rebel and maintain their freedoms in times of need, now that they only sent a share of their profits to the central government for the upkeep of a central standing army, there was no way for them to promote the succession of a more favoured emperor. Theoretically, there was no check on the Mughal state’s potential for tyranny and numerous different solutions had been proposed. Calls for an empire wide representative body were stoked from the beginning of the century until the establishment of the Rajasangha. Functionally however, it became the role of the independent mercenary or warrior-ascetics to threaten rebellion to keep the state in check and in 1724, the Sikh guru formally put forth the notion that the independent military labour pool was essential for guaranteeing the freedoms of the people should the state fail to maintain them. Individual companies were frequently larger than 50,000 and the number of Sikhs volunteering for military service independent of the empire was 100,000- a legal maximum that the Imperial Camp had been able to impose. Another important factor was that as many of these groups had heavy religious overtones such as the Gosains, Sikhs and Barha Sayyids. Despite having military organisational structures as complex as any western monarchy, and having long since expanded from their mercenary role into commerce, politics and government service, they were still primarily defined by religion and any attack on them undermined the state ideology of freedom of religion.

The solution devised by Jahanzeb Shah paralleled his treatment of rivals for the throne. Just as he sent his brothers off to distant lands so they wouldn’t be threats, he started a policy of indirect expulsion of military men not controlled by the empire. He did this by encouraging them to hire themselves as mercenary forces to powers outside the subcontinent, subsidising Mirza Isaac’s business of ferrying mercenaries across the world, and encouraging foreign rulers and magnates to hire them. Mercenary groups now came to the forefront of military innovation in India as they were the ones who were forced to innovate and adapt to local situations and tactics. While the Mughals had experimented with European style infantry in the Deccan rebellion, it had been the Gosains who first fully incorporated it and used it to great effect in Burma. As these groups had more limited sizes than that of the empire, they were more likely to face numerically superior opponents and were thus forced to seize other advantages in a way that the Mughal state hadn’t needed to since the days of Akbar. Another practice begun by Jahanzeb Shah was to promote the demilitarisation of many of these groups by rewarding mansabdars who used this labour pool in order to construct palaces, schools, religious buildings, planned urban

areas, gardens, roads, factories and caravan sarais. Further, the standing army of the state itself was often hired out to foreign princes and kings and this was another factor that sharpened the military's competitive edge. While normally a danger with hiring mercenaries was that they would take control themselves, Jahanzeb Shah required all mercenaries leaving India to fill out forms detailing the terms of their contract, and guaranteed that if that contract was broken, then the Mughal state itself would lead its own armies against these mercenaries.

Mercenaries who especially distinguished themselves in battle then secured an audience with the emperor through recommendation and their knowledge thus diffused through the imperial structure as well. Thus in the period before the struggle with China truly began, the Mughal army benefitted from a formidable tradition of improvisation and discipline. In fact, they were often of more use in pitched battles against large organised opponents than the standing army of the state- as the standing Mughal army was primarily directed around maintaining order and putting down rebellions in the provinces, they were mainly focused on guerrilla and anti guerrilla operations. While ideally, they were trained in pitched battles that had made the state so deadly in its first century in practice these were relatively rare compared to the recurring problem of guerrilla warfare and as such the state had to focus on these. In counter insurgency, the state largely depended on the “Shantishastra” and written by Maharani Tarabai, the daughter-in law of Shivaji and wife of Chattrapati Rajaram. She aimed at reforming the Mughal counterinsurgency techniques of her predecessors era which could include collective punishment of communities that she noticed were counterproductive. Her principles are used to this day in global counter insurgency operations and include:

1. Gaining support of the local people- Tarabai knew first hand that the local population provided insurgents with recruits, food, shelter and finance and that in combatting this, the state needed to provide physical and economic security for them and protect them from insurgent attacks or propaganda.

2. There must be a clear political countervision that can overshadow, match or neutralise the insurgents narrative. This narrative must involve political, social and economic measures that convinces people of the benevolence of the state and the opportunity for advancement it provides.

3. Practical action must be taken to match the state’s narrative, and address the specific grievances of the insurgents.

4. Economy of force- Tarabai, steeped among the stories of the Maratha aristocracy, had ample first hand accounts of how certain factions among them had hardened themselves against the Mughal state when it overreacted to the provocations of Shivaji and the earlier Malik Ambar insurgency and destabilised the whole region.

5. Big unit action may be necessary to break up large guerrilla forces who would otherwise require a full pitched battle into smaller bands that can be dealt with by police and smaller units.

6. Focus on the Shivaji tactics of small units of comparatively light cavalry, designed for complete mobility that can locate pursue and dispatch insurgent units. While control of the numerous forts dotting the country is important, they shouldn’t be overused as the field would then be conceded to insurgents. They must be kept constantly on the run with patrols, ambushes, roadblocks etc.

7. Counter-insurgent forces need to be familiar with the local culture and language- this was especially important in the polyglot environment of the east indies and the subcontinent that Mughal forces were used to. The vast majority of dictionaries for the vernacular languages of asia were originally compiled for military purposes, as well as the imperial ethnographies. Jai Singh’s project of collecting folklore, local ideas about history, legitimacy and religion was the most ambitious imperial ethnographic project and it was widely circulated around military forces, with candidates required to know the history of a region before they could be appointed.

8. Organisation of a systematic intelligence effort. As well as the questioning of civilians and the structured interrogation of prisoners, more creative methods must be used. The application of the intelligence side of the arthashastra had been well underway before the overhaul of laws by Prithvi Narayan Shah, and its techniques included the creation of a class of wandering ascetic spy- usually taken from the sikh, barha sayyid or gosain mercenary groups, these spies were free to wander anywhere, their presence was not unusual at any place and they were held in great respect. Further, the state used companies of mercenaries to pose as groups working for the insurgency to feed back information.

Equipment and Weaponry

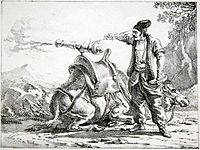

This period saw the first use of camouflage uniform, as the mercenaries who first went with Sikander Shah to Iran pioneered. By the time they returned, it had been adopted as a common uniform for all Mughal shock infantry infantry. The musket in India had similar origins to its European counterpart but had evolved differently over the centuries, with a focus on accuracy instead of rate of fire. This had led to thicker and longer barrels, recoil pads and slings. The flintlock was adapted into Indian muskets by the Barha sayyids in 1698 and then adopted by the Mughal military overall in 1715.

Muskets were a central part of the Mughal infantryman’s equipment- despite this the bow did not fall out of favour for a long time. In fact, Mughal musketeers were often supported by archers, whose high volume of fire covered the more deliberate work of the musket. In Jahanzeb Shah’s army, there were twenty different pay-grades for musketeers. Steel bows which wouldn’t warp in humidity were a specialty of Indian manufacturers.

Indeed, despite advances in technology and tactics, much of Indias military manufacturing in the 18th century remained very traditional in relation to European output. Given the limitations of smoothbore weapons, the advent of gunpowder didn’t make the horse archers way of war obsolete- arguably until the creation of a practical rifle musket and the concurrent advances in field artillery, the horse archer was the most formidable individual warrior anywhere in the world. His equipment consisted of at least two different bows- a lighter one for use in the saddle and a heavier one for use on foot. The steel bows invented in India were slightly less flexible but much more durable in humidity and as such were used by all Mughal archers operating south or east of the Gangetic plain. A skilled user could fire over six shots a minute, from over 300 yards. They also carried a variety of weapons for close quarters use, including lances (which fell in and out of fashion but were always being used by at least hundreds of thousands in India throughout the 18th century), swords, and axes. As the archer was still a major threat on the battlefield, armour was still necessary to an extent that it wasn’t in Europe any more. There existed a difference between heavy and light cavalry, where the latter was almost exclusively composed of central Asians who had spent their whole lives in the saddle and could specialise in mounted archery and the former were often composed of Indian troops, especially Rajputs and Marathas, who were more specialised in shock tactics. The main revolution in cavalry arms happened owing to the influence of Shivaji and then later Tarabai, who successfully advocated for the classification of terrain into different types, and in terrain like the Deccan, rugged, overgrown and with poor visibility, for the introduction of a different type of light cavalry- armed primarily with sabres, short lances, carbines and pistols. This new breed of cavalry was specialised in ranging over territory and was used to great effect by mercenaries and the military throughout the Indian ocean world, however in pitched battles it occupied mainly the same role as the horse archer.

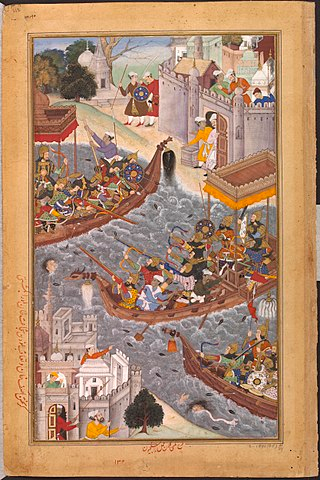

From the 1690’s Aurangzeb had directed the use of cannons built in the European fashion, with massive investment in the mining industry of Karnataka. This replaced the earlier style of cannon making, which didn’t use a Catalan forge- instead cannons were made in individual pieces then bolted together, which could result in them breaking when used. The investment in the iron mines of Karnataka also revolutionised the potential for a Mughal blue water navy- now that cast iron cannon were relatively inexpensive, galleons, frigates and ships of the line were in reach. These were built from teak and sundari and thus were four times as durable as their European counterparts.

Rockets were a very common weapon in Mughal india from its inception- while other regions of Eurasia had abandoned the rocket with the advent of muskets and newer firearms, Indians had continued to innovate with them. It had a range in the hundreds of yards, was inexpensive and easy to carry. The ammunition train of a typical army in this period could carry hundreds of thousands of rockets. While they had very bad accuracy, there were ways of improving this, such as the purbiya rocket- essentially a primitive bazooka which was a handheld metal launching tube. Further, in 1736 the Karnataka rocket was popularised which had an iron casing and further improved Indian rocketry. By the mid 18th century, Indian style rockets were used in almost every European military.

Another class of extremely flexible and dangerous anti-personnel weapon was the chaturnal, or camel mounted guns, which could also be mounted on elephants. They fired lead shot and projectiles the size of baseballs, and despite needing to stop to fire and reload were much more mobile than the other field artillery of the day. They were cheap and could be fielded in large numbers- a typical field army in a pitched battle would have hundreds of them throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. They had no European equivalent at this time but European powers made greater use of them as camel warfare became ubiquitous in the North American, Indian Ocean and North African worlds.

Tactics in Pitched Battles Against Large Armies

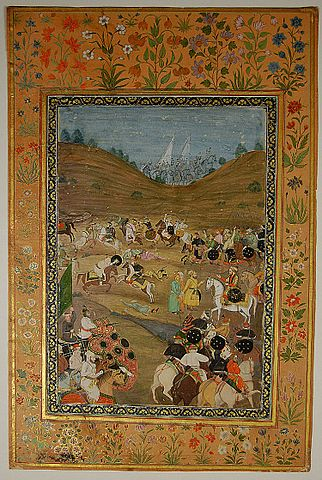

Indian warfare encouraged trench warfare, skirmishing, small unit operations and the tactical defensive. The horse archer was an indispensable component of the military machine, the most skilled and versatile part of that system without a true equal anywhere in the world- including Europe. They were ideal scouts and screening elements and were indispensable in countering enemy cavalry. As a prelude to shock action by their own heavy cavalry and infantry, they would rain a hail of arrows down on enemies or lure them out of position with a feigned retreat. In the standard Mughal set-piece battle based on the tactical defensive, some units of horse archers moved forwards to act as skirmishers while others held the flanks and enveloped the attacking enemy. Constant movement was the key to avoiding a collision with opposing cavalry or return fire from less mobile opponents.

Central Asian cavalry was trained to employ a much more destructive version of the European caracole, with a number of variations- one mirrored the European infantry countermarch but for cavalry. In addition, heavy cavalry was used to deny enemy light cavalry access to given areas and keep them at a distance. Along with horse archers, they exploited breakthroughs and executed flanking manoeuvres.

Nevertheless, cavalry couldn’t win battles on its own. The distinction between infantry and support personnel was not always clear, especially given the highly militarised society where even civilians routinely bore arms. In a military system that depended so heavily on entrenchments and field fortifications, all infantrymen could be called upon to dig, chop, build and carry (this was one of the factors that enabled Jahanzeb Shah to promote mercenary groups being used to build palaces and irrigation works- if youre going to need to know how to build things very quickly on the battlefield, it can’t hurt to practice on civil works)

True heavy infantry had always been rare in Indian warfare, and was mainly used in areas where cavalry couldn’t operate properly- thus they were very useful when cities became the sites of war, or for fighting in the elaborate field fortifications of the time. They also had some use in the open field if used correctly- they could attack and overrun enemy formations that were out of position, fleeing or disrupted by artillery and small arms fire. They were also useful in counter insurgency operations as they could root out enemy skirmishers, especially those under cover or who had dug in. To pass through the danger zone of enemy artillery and small arms fire as quickly as possible, Indian shock troopers employed a tactic similar to the highland charge of contemporary Scotland, approaching the enemy in the open, almost at the dead run. As they had to sacrifice armour for mobility, they were the ones who could wear uniform recognisable to contemporary Europeans- camouflage or khaki to break up their outlines as a target. In fact, a few armed religious ascetics even fought naked, resembling in form and function the Celtic warriors of Ancient Europe.

Since the arrival of Louis XIV’s ‘presents’ and military advisors in India, heavy infantry carried bayonets- before closing to engage in close quarters combat, they would fire rounds of projectiles to damage and disorient the enemy. As they got closer they could use other projectile weapons, especially the chakram made famous through the Nihang armies of the Sikhs, and only at the last minute would they fix the bayonet onto the rifle.

While missile troops such as musketeers and archers did need to be able to defend themselves in close quarters, their best bet was to avoid close combat altogether. Unlike their western contemporaries, Indian musketeers and foot archers almost always fought in open order or from behind cover.

While European style linear formations did offer two significant advantages; they allowed the concentration of fire which was important when the primary missile weapon was a slow firing inaccurate smoothbore musket and an individual infantryman couldn’t do much unsupported. Secondly, compact formations allowed infantry armed with pikes or bayonets to make effective shock attacks and also resist shock action by opposing infantry and cavalry. However, they turned large groups of infantry into easy targets. In Europe, the tradeoff of increased vulnerability in exchange for greater firepower, mass and resiliency was considered acceptable. This was not the case in India, and Babur quickly abandoned his experiments with linear formations modelled on the Janissaries in the early 16th century.

As Indian infantry was dispersed, it was up to the individual squad to make a significant impact on the enemy. This was accomplished by producing a greater rate of fire or by making each shot count. Rapid fire was delivered by bowmen and slower but more damaging fire cam from musketeers- as mentioned above, Indian muskets were evolved for accuracy and whose training emphasised marksmanship. Users of both weapons would have formed mixed squads, where they could complement each others weaknesses. As opposed to the uniformity of weapons in contemporary European armies, the composition of a small unit of Mughal foot soldiers in the 18th century was much closer to a modern infantry squad- a large number of lighter, rapid fire weapons (bows/assault rifles), a few more precise weapons (muskets/ sniper rifles) and possibly even “crew served” weapons (jezail heavy muskets/machine gun or rockets/mortars).

These squads tended to fight from behind cover, while besieging or defending forts or while fighting in the front lines and using entrenchments or a wagon laager as protection. A number of them, however operated in the open. In the traditional central Asian battle array, the irawul (vanguard) was a contingent of horse archers used for harassment and skirmishing. By the Mughal era, infantrymen were also assigned to this task, as muskets could disrupt a charge by fully armoured heavy cavalry. Musketeers fought while lying prone on the ground or in foxholes if they were given enough time to prepare (which explains the emergence of integral bipods to increase accuracy long before in Europe). This meant that they were almost impossible to hit by enemy musketeers and they were difficult for cavalry to engage- the options were to stop and root them out or to pass them by and risk them re-emerging and firing from behind. Cavalry could also ferry these skirmishers around the battlefield by escorting mounted infantry into their fighting positions and then leading their mounts to the rear. The need for soldiers to fight as small groups meant that small unit tactics were much more advanced in India than in Europe- evidenced by the respect and relatively generous pay granted to platoon leaders (panjehbashi/commander of 50 and dahbashi/commander of ten) also indicates such a development, and explains why European observers thought that these armies had a bloated officer class.

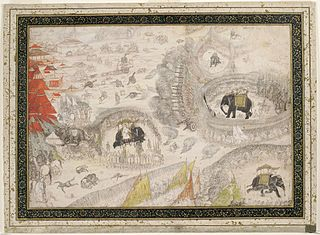

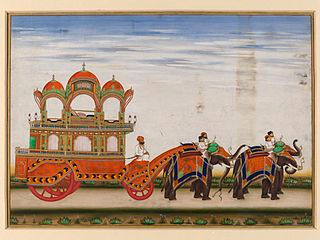

The role of elephants in warfare had been completely revolutionised with the advent of gunpowder, as they were large inviting targets for musketeers and artillery, and when injured or scared were as much of a danger to their allies as the enemy. However, when camel guns were invented, elephants became mobile standoff weapons, delivering rapid and accurate fire from beyond small arms range. Their size allowed elephant mounted gunners to more easily see and engage distant targets, and this height advantage meant that they remained popular as commanders mounts and mobile observation posts. In many cases the animals used for this purpose were hobbled with chains so that they could not bolt if startled or injured.

One of the most consistent criticisms made by Western observers was that Indian soldiers lacked discipline. Linear infantry formations allowed much more effective surveillance and command of the individuals within and soldiers were prevented from misconduct by close supervision of officers and many comrades. Such cohesion was not possible in more dispersed Mughal units. This style of combat actually required a higher level of discipline and initiative from individual soldiers, who had to manoeuvre, attack and make decisions out of close contact with their superiors. This did not preclude them from acting as part of a team and according to a plan but it did make rallying and recovery after a defeat much harder. Armies heavily reliant on cavalry and fast-moving infantry scatter very quickly when they smell defeat. Famously, in the battle of Samugarh between Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb, when Dara descended from his elephant and could not be seen by his army, the cry went up that he was dead and many laid down their arms right there and then.

European observers were also appalled by the seeming timidity of Mughal troops, who in many cases appeared hesitant to charge and did no always stand their ground in the face of an assault. However, the ability to fight from the tactical defensive and withdraw successfully if called upon were hallmarks of the Central Asian tradition that had seen steppe conqueror after steppe conqueror dominate Eurasia. Aside from the use of misdirection and feigned retreats, commanders and individual soldiers were expected to extricate themselves from untenable situations and to preserve the lives of themselves and their comrades regardless of any considerations of personal honour, in a throwback to the famously casualty averse culture of the Mongol armies.

Commanders raised in India were often contemptuous of the stubbornness and unchecked aggression of groups like European chivalry and even the Rajput nobility. Aurangzeb noted that “Turanis feel no despair when commanded to retreat in the middle of battle, which means to draw the arrow back, and they are a hundred stages remote from the crass stupidity of the Hindustanis, who would part with their heads but not leave their positions”.

Further, surrender after the death of a commander often made logical sense- at the aforementioned battle of Samugarh what would have been the point to keep fighting after Dara was dead, their faction was leaderless and their mission over? Who would they be fighting to enthrone? Resistance to the bitter end made no sense in a political culture where the losing side of a war was always granted amnesty and were often rewarded for their bravery by the victor- who now had to smooth over relationships between them and their nobles in their new sovereign role. While fighting against external enemies, Mughal armies always maintained their cohesion and recovered after terrible losses, including generals, as they knew amnesty would not be coming from less enlightened rulers.

Sieges and Fortifications

Mughal armies usually carried with them large complements of labourers to build fortifications. These creations ranged from trenches to elaborate fortresses built of earth, mud brick and logs. After the initial period of expansion in the 16th century, 17th century Mughal warfare moved from being primarily pitched battles to sieges. Their enemies had fully embraced the military revolution in their design of fortresses, though here, as in musket design, this looked different to the European solution.

In Europe, medieval castles had thin high walls and the military revolution saw low fortresses created with slanting sides that presented less of a target to enemy artillery. In India, things were different- Rajput fortresses from the 13th century onwards were constructed with alternating concentric rings of moats, earthworks and enormous stone walls, some of which exceeded 15 metres in thickness. Many builders also had the luxury of commanding terrain on which to place their forts- mountains and hilltops, apart from making defence easier, made the sprawling footprints of European forts impractical. The Deccan especially simply built higher and higher and they already had good defensive locations of lone mountains in the middle of a flat plain to build in. Here, the logic is not to make the fort less of a target, but to have such range and command of the surrounding terrain that enemy artillery cannot get within range of attacking the fort.

In the 18th century, construction of forts in India proper ceased, owing to the pax mughalica that forbade the construction or repair of fortifications not owned by the royal family. However, with the expansion into much less defensible borders past the Hindu Kush, deep in central asia, it was necessary to build vast lines of fortresses. In the steppe, these tended to be in the model of the trace italienne thanks to French mansabdars as the flat plains precluded Deccan forts. However, on the Chinese border, which followed mountain ranges throughout, the traditional Mughal fortress was more suitable, attested by the number of forts in central asia with the suffix -garh.

Sports and Military Training

The 18th century saw the creation of empire wide tournaments of certain sports, which were appreciated both as mediums for training soldiers and also for enjoyment and socialisation. Villages and towns maintained akharas, or gyms, where aspiring soldiers practiced martial arts. Sports included gymnastics, boxing, wrestling, fencing, staff fighting, mace fighting, archery, sharpshooting and the Mongol “three Manly Sports”- wrestling, horse racing and mounted archery. In Bombog Kharvaa, mounted archers shot at spherical leather targets from a variety of positions. In teams, people played equestrian sports like buzkashi and polo, which sometimes degenerated into rowdy near-battles. In the gladiatorial arena, combatants risked serious injury and even death.

The continued use of military elephants also justified their use as gladiators in entertainment- in a famous anecdote, when Shah Jahan and all four of his sons had been watching an elephant fight they suddenly charged at them and only Aurangzeb had the presence of mind to hurl a spear at one of them, distracting it long enough for its opponent to resume the fight. Despite the reform of elephant fighting by animal rights groups in order to maximise its accordance with the natural wild behaviours of elephants and to increase welfare, broadcast elephant fights remain a popular form of entertainment. Pit fights come in all weight classes though, and animal fights popularised through Mughal patronage include buffalo fights, camel and antelope fights and even tiny creatures such as quail.

In fact, the place of animals in court culture was the first step in the development of animal rights movements. Animals were anthropomorphised, and if an animal performed well in the military or in a sport, it was given a reward. Pioneering experiments that derived methods for determining what conditions and luxuries an animal prefers, what it benefits from, and how they experience things different to human biases, which form the basis of animal welfare of all animals in captivity were originally conducted to reward animals at the Mughal court. Jahangir built a tomb for an antelope that had excelled in the fighting ring, and Aurangzeb exiled a war elephant for not treating him with the proper respect.

The 18th century also saw more cerebral activities receive empire wide tournaments- board games that had been restricted to the court now diffused across the social spectrum and included parchesi, chaupar, shahtranj (chess).

Actual military training was also not lacking, especially after the creation of Jahanzeb Shah’s military academies. Here, standard texts included Dastur-e Jahan Kusha (Method of World Conquest), or Faras-nama (Book of Equine Veterinary Medicine). Many official and semi-official accounts tended towards hagiography if not outright propaganda and solidified commitment to the Mughal state by glorifying its history. However, among the accounts of heroes “enjoying the wholesome sherbet of martyrdom” and wicked enemies “forced to taste the bitter wines of defeat”, there are genuine efforts to think critically and learn the lessons of past campaigns. In 18th century texts, produced less hagiographically, the focus shifts decisively towards military analysis not just of India but of the entire world, seeking to explain why people fight the way they do and whether what they do is better in their situation than the Mughal ways. Additionally from the Subotainama of 1746, Mughal military theorists tried to discover what about the early Mongol campaigns made them so successful and whether they could be replicated.

Logistics and Non-Combat Operations

A key weakness of the Mughal military when it was on campaign was the snails pace that it travelled at. However most of the vast numbers of camp followers of the main Mughal army were skilled and well-paid professionals- pioneers, porters, animal handlers, cooks, clerks, physicians, engineers- who were vital to its success. They kept troops fed, sheltered, healthy and equipped in the field and cleared the way for their progress, building roads, bridging rivers, and at times literally reshaping the terrain in front of them. As the 18th century progressed and the quality of roads became better throughout the empire, the need for these groups diminished and the army became faster anyway. Additionally, while normally they never demanded shelter or food from the local population, from Aurangzeb’s reforms on, individual platoons in counterinsurgency missions were encouraged to request the local population to supply them with food and shelter. They weren’t authorised to seize these things if denied, and were encouraged to never feel like a burden and help with routine chores while staying with people in order to ensure the people supported the state. While on campaign in hostile territory though, these measures weren’t available and the army needed to take everything it needed with it as it travelled.

From Azam Shah’s reign on, an examination was available for blacksmiths, carpenters and craftsmen that proved their ability to produce quality work. With this qualification, they were allowed to supply equipment to the Mughal army, and it allowed them to charge higher prices for other customers as well. This meant the army no longer needed to take men of these professions with them wherever they went, and this further sped up the pace of the army. Once again, this wasn’t available in other states and so the army needed to take all these people with them while on campaign- it would undoubtedly have been much easier to simply force local craftsmen to conduct repairs and source equipment, but not only would this allow for low quality work to enter the army, it was seen as unethical. The soldiers were fed as units in large canteens by a small army of cooks led by a mir bakawal, of Master of the Kitchen. Mir Manzils, quartermasters and logicians, organised and distributed uniform, weapons and food taking into account special dietary requirements. All of this was transported by Banjaras- and this typifies most of the Mughal government. There was a small cadre of state employees supplemented by a wide range of private contractors as needed.

Mughal support staff was much more closely integrated with combat arms than in contemporary militaries, and commissioned officers were routinely delegated to supervise the more mundane elements of the army. Many of these labourers were paid on the same scale as infantrymen, and recruited and assigned to mansabdars in the same way as infantrymen.

Here too, animals remained vitally important. Even as their use in combat had diminished, elephants had remained living tractors and bulldozers, used for pulling the heaviest artillery, towing boats, clearing timber. Pay records note a staff of 43,592 elephants on duty in 1742 and there were even larger numbers of draft animals. In the central Asian theatre between 1738 and 1750, the Mughal army deployed 200,000 oxen. All of these animals were as carefully regimented as other branches of the army. They were listed on muster rolls and were subject to periodic inspections.

Essentially you don't need need to know this, but it is information from the single scholarly work on the Mughal military as a fighting force in the past 100 years. For those of you who actually do get through it, there are some interesting tid-bits ive dropped in to tease future updates. In essence though, its very difficult to say why the horse archer declined historically OTL, and I hope you'll forgive me if I put forward the proposition that Maratha-style cavalry with pistols and carbines, given enough training could potentially fill the same role in a pitched battle, which I don't know for sure could happen.