It does seem like the story is heading towards Rosencranz' overconfidence leading him to commit more and more troops to an unfavourable battle somewhere down the line. Though the Union still has a rather major manpower edge I do believe, even accounting needing forces on more fronts than OTL.

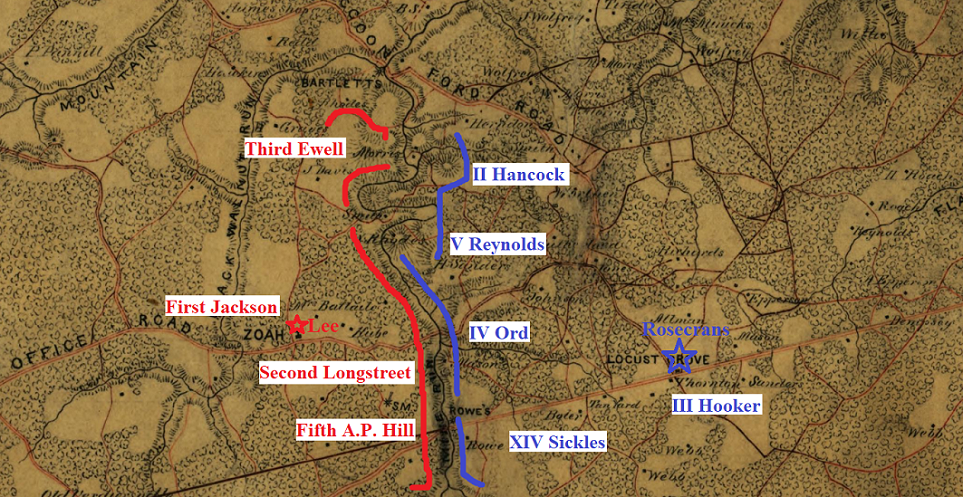

In all fairness, he has done to Lee what Lee successfully did to McClellan twice, once in 1862 and in 1863, while saving Washington from the threat of a second siege. Driving Lee to his "last redoubt" may be an exaggeration, but if he can break Lee's army at Mine Run then he can start slowly forcing him back to Richmond.

Even if he takes serious casualties, he does have an advantage in that there's more Union troops to call upon.

Currently the Union forces are structured (roughly) as such in the East:

In the Department of New England there are roughly 60,000 men spread from Maine to Connecticut, with 20,000+/- tied up in the Army of New England in Maine and another 40,000 men - which includes a lot of state troops and other formations guarding the harbors and cities - who are simply keeping the guns ready.

The Department of New York (southern New York state, primarily New York City) has about 15,000 men, 12,000 in garrison of the city itself and a spare brigade or so of troops who can be moved around in response to an emergency. I should note that these are almost all state troops who have been placed on duty "for the duration" who don't leave the state unless asked. New York, especially under its new

Copperhead Democratic Governor is quite prickly about the whole war.

The Department of the Lakes (Canada West, northern New York, Michigan, Vermont New Hampshire) has roughly 63,000 men. Most of those are the 45,000 men garrisoning Canada West (including the XX Corps) then the much truncated "Army of the Hudson" numbers roughly 15,000 men, mostly involved in garrisoning Albany and staring down the British based north at Ticonderoga. The remaining 3,000 are sundry militia and garrison troops as far ranging between these states and Vermont and New Hampshire.

I already laid out the larger Union forces directly facing Lee on the Potomac in Chapter 84, but suffice to say there are about 123,000* men "in the rear" as it were who could be called upon to replenish any losses that Rosecrans takes. This of course assumes that the war with Britain ends soon, and that they can be moved quickly in response to an emergency.

*I should note these numbers are subject to the same attrition as other units in 1864 with many enlistments expiring, and while on paper starting in January of 1864 that's broadly accurate, probably the number has shrunk by close to 20,000 with expiring enlistments and desertions, so its probably closer to 95-105,000 men who can be looked at as a reserve.

You betchya! Bud the Spud will have a few choice words!

Oh he may! The Spud Wars may be a vicious thing come the peace!