Chapter 98: Two Victories, Two Defeats Part I

“The victor is not victorious if the vanquished does not consider himself so.” - Ennius

“The Army of North Virginia was not the same force which had marched into the North in 1863. Now numbering barely 46,000 men, Lee’s invasion was a gamble of the highest order. While he was able to, for a time, conceal his true strength through his cavalry, it would only be a matter of time before Pope’s army, still significantly stronger with over 80,000 men[1], could bring itself to bear on his small force.

Lee’s goal then had been to find suitable ground and then goad his opponent into battle. Pope had been too eager to oblige…

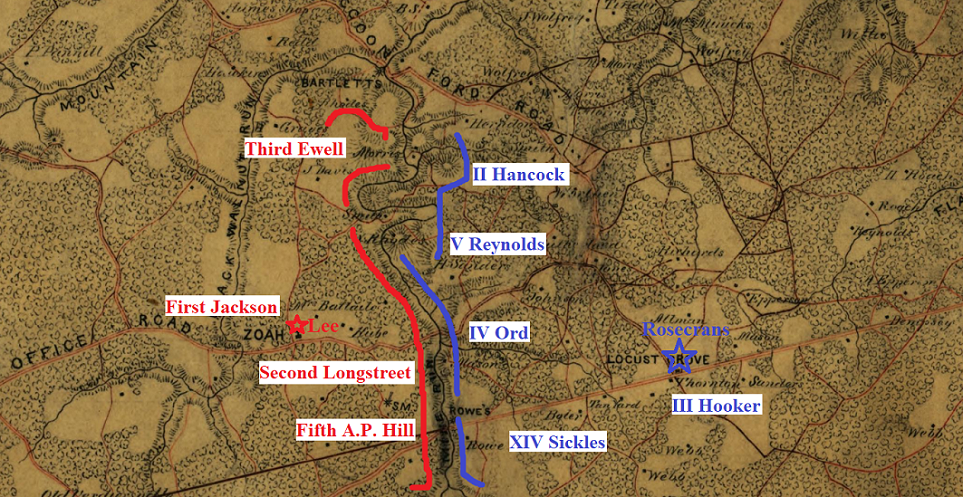

The ground Lee found at Pipe Creek was a dream come true. A long line of naturally defensible ground which any Union army wishing to engage him had to cross. Even if an army did not want to attack, it would be enticed by the uncomfortable geography. By intersposing his army along this line of advance, Lee cut off Baltimore by road, sitting squarely on the major outlets which could reach it. The Hanover Pike which ran directly from Hanover in Pennsylvania to Baltimore cut one avenue, while the Taneytown Pike ran straight through the center of the line. To his great advantage, supporting roads ran all through his rear, allowing him to exploit his inferior numbers with mutual support. All of these routes were eminently defensible, and Lee sought to exploit the ground to the fullest. Just as importantly, the position left him the option to retire on Winchester and then Catoctin Mountain towards Virginia should the battle go against him.

Despite his appreciation for the ground, the whole Pipe Creek position was roughly twenty miles in length from Middleburg to Manchester, and Lee had to man all the points he possibly could.

On his left, near the village of Middleburg, the ground was funneled by rivers and slopes, which made approaching it difficult and Lee’s left wing would be easily defended. As such he detached only McClaw’s division to hold it, confident in the ground’s inherent defensibility. The remainder of Ewell’s corps was spread thin from there to the Taneytown Pike where it met Longstreet’s flank.

It was along that section of Pipe Creek, near Union Mills, that the ground changed. The landscape broadened out, and the hills were not as steep making the terrain more favourable to large scale maneuvers of the sort that could break Lee’s army. Across the creek an advancing Union army could easily meet at Taneytown where it could attempt to force a crossing and maneuver to split the Confederate army. It was here he concentrated Longstreet’s corps and the reserves, Hood’s division alongside that most famous of brigadiers Chatham R. Wheat.

The far right of Lee’s line was anchored at Manchester, where the line rested against Parr’s Ridge. However, this position was vulnerable in its rear. Lee did not have the strength to man the whole line, and with only two divisions of Hill’s fifth corps to cover this section, Lee asked Stuart to do the unthinkable, detach Fitzhugh Lee’s division and dismount half of them to serve as infantry. They would be the extreme right of his line of battle. Though he established lookouts and a signal section to watch for a flanking force, he knew he was gambling on such a small force to hold the less defensible flank…

Lee's Pipe Creek Line, August 30th, 1864

…Lee once again went to work earning his name “The King of Spades” and his men, almost overnight, threw up earthworks which would have done any regular proud four years earlier. Chest high breastworks were established, sheltered gun positions, and field hospitals were thrown up to provide for the wounded, with a wagon train waiting to withdraw in case of disaster…

When Pope’s first units began massing at Taneytown on the 29th of August, his forward scouts from III Corps began to come into contact with the Confederate lines. It was the 3rd Division under Kearny which first made contact near Union Mills. Kearny was depressingly unsurprised by the discovery of Lee’s fortified position. He wrote to Hooker saying “...the speed with which Lee has made this position similar to the Mine Run line is a credit to the foe. We must not attack head on lest all the embarrassments of the action of June be repeated.”

When Hooker himself rode forth to inspect the positions alongside Hancock the next morning, the two generals despaired of a frontal assault. Hancock, remembering well the carnage inflicted upon British forces maneuvering through New York the year prior, all but pressed for the army to try and maneuver around Lee. “General, for God’s sake let us not pay a price in blood for this position.”

Pope did take these demands seriously, having suffered enough reversals in the West. He would spend the 30th and the 31st of August recconitoring the enemy lines as he maneuvered into position. Gregg’s cavalry proved its worth as it rode around Parr’s ridge, with a too small cavalry screen to prevent them from finding the extreme end of the Confederate position. Intrigued, Pope would ride out on the evening of the 31st to see for himself. Upon finding the edge of the Lee’s great works he became excited. There could be no repeat of Mine Run, instead he would flank Lee and route his forces. To do so, Hancock’s II Corps and a division of cavalry would maneuver to Lee’s flank and roll it up, crushed against the remainder of the Army of the Potomac.

To that end he planned that a vast attack should fall on the center of Lee’s army where the ground was suitable. Hooker’s III and Couch’s XIV corps would fall on the Confederate center like a sledgehammer. To prevent Lee from concentrating his forces, Meade’s V Corps would pin the Confederate left and act as the right flank of the army. Ord’s IV Corps would press the Confederates in the center and near Manchester. He believed this would ensure that no forces could support one another.

What drove Pope’s purpose home was the capture of a Confederate deserter who was interrogated by Bureau of Military Intelligence agents the night of the 30th. He said Lee’s forces had been engaged in a raid, and were now tired and footworn. They were only hoping to delay Pope, not fight a battle. This information all in hand, Pope ordered the attack begin at 7am on September 1st…

The one flaw in Pope’s plan was, thanks to Lee’s higher elevation, his men had been reporting on the Union movements all morning. Thus, when Hooker and Couch’s men went in, their attack was well anticipated and the bulk of Longstreet’s corps was prepared to meet them as they converged at Union Mills…

Even with a flanking force from Slocum’s division attempting to tie down Longstreet, he needed only a brigade to spare before he moved the bulk of his three divisions to Union Mills. The lines at this position were strong as the crossing over could be compelled by a large force. As such, Early and Anderson’s divisions stood shoulder to shoulder, well supported by guns on the higher ground to their rear. However, his line was focused on two positions known as Perry Hill and Mahone’s Hill, just across Pipe Creek from Union Mills. Dug in ahead of them, Longstreet had prioritized Early with defending Mahone’s Hill, and Anderson with Perry Hill, with odds and sods acting as reserves in his rear.

Despite a definite numeric superiority, Hooker knew he was sending his men into a death trap. The rebel artillery had received ample time to site their guns, and it was Kearny’s opinion that “it was a killing field…the first regiment across is sure to be decimated.” The rebel gunners held a similar view stating “Once we open up, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

This was to be proven unfortunately true for the men of John Martindale’s division. The leading regiments struggled waterlogged across the creek, blasted by rebel artillery, only to then be “scalded” (Hooker) by rebel fire from the trenches. Though they pushed on, egged on by Martindale, conspicuous in his bravery for riding behind the lines to urge the men forward, the attempt to force the ground ahead of Perry Hill at first ended in bloody repulse.

Kearny’s 3rd Division fared little better. The opening attack managed to make it across Pipe Creek intact, but petered out much to Kearny’s displeasure. He railed at the soldiers who would not go, but by 9am, he too was forced to admit that he would require the full force of the corps to cross…

On the extreme left of the Confederate lines, Meade advanced cautiously against the rebel works. The ground was unfavorable to a full advance, so he probed with Whipple’s division cautiously, and was stung for his efforts. The cautious maneuvering turned up “bad terrain, good earthworks, and rebel bullets,” as Meade would later write. His attacks were not pressed in earnest, something which would earn him the great ire of his fellow commanders…

On Longstreet’s right, Ord’s men made surprising advances up the rocky ground near the Hanover Pike. King’s division pressed French’s troops in, but they held tenaciously, and soon the terrain told in their favor. The presence of Pender’s division held the line and Ord’s attacks came to naught. By 12pm the fighting would peter out, it would all be in the center and the flank…

In retrospect, the day may have been won there at 12pm had the coordinated assault by Couch and Hooker gone as intended. Striking up the Littletown Pike, it had the possibility of breaking the Confederate army in two as Pope had hoped. However, Longstreet had sited his defences skillfully, and such an attack had been observed and anticipated. Lee was granted an unexpected reprieve by the lackluster performance of Meade on the flank, and so detached Jones’s division to support the center.

Hooker and Couch’s six divisions would organize and then launch a full assault across the creek. The men of III Corps under Grover, Naglee, and Kearny, alongside Couch’s divisions under Martindale, Sturgis and Howe, would maneuver to launch an assault en masse, with the goal of pinning the Confederate center in place and, if practical, divide the Confederate army in two. This grand attack formed up in full view of the Confederate artillery, and the whole army knew hell would soon follow…

Kearny’s 3rd Division again led the charge, his men pounding across the creek into the teeth of Confederate entrenchments. Kearny, leading from horseback, had a horse shot out from under him, remounted, and promptly lost a second. When an aide asked him if he would rather walk, Kearny simply replied “It would be unchivalrous to the enemy to deprive them of such a splendid target, and discourteous to the men to invite them to take the fire instead.” However, leading by sheer determination, they took the first Confederate line with the bayonet. Following this, they charged straight for Mahone’s Hill. Supported by Naglee’s men, they broke through, only to be repulsed, but again surmount the hill and place their banners on top…

Couch’s men, though slightly less zealous, hammered their way through the lines toward Perry Hill…

In the hinge between the two corps across at Union Mills, the divisions of Sturgis and Grover plunged into the Confederate line. In spite of shot and shell they maneuvered forwards, charging across the creek and managing to break the line between Early and Pickett’s divisions. The battle might have ended here with the Confederate army split were it not for the Louisiana Brigade.

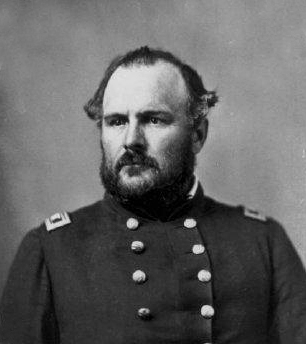

Brigadier General Chatham Roberdeau Wheat had raised the 1st Special Battalion upon returning to America after serving with filibusters abroad. Largely street toughs, Irish and German immigrants, they were a hard fighting and hard living unit which respected Wheat’s tough but fair leadership. His men had performed well in 1862 and again during the Siege of Washington, but had often been under various administrative punishments for fighting with other men in the army. Wheat himself quarreled with every commander placed over him, which many speculated had cost him divisional command.

On September 1st 1864 however, Lee knew he would need fighters, and so the ever quarrelsome Louisiana brigade was part of the army reserve. The 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 14th Louisiana and the “Special Battalion” of Wheat’s original fame[2] formed up in the rear of Longstreet’s lines. Only 1,800 strong they were the seam that was meant to hold the army together.

When Sturgis’s troops forced their way through Longstreet’s lines, instead of finding themselves in the open, they found the Louisiana Brigade formed and ready to meet them in their zouave uniforms. Firing a volley, they advanced steadily under the stern leadership of Wheat. Though taking the brunt of the emerging Federal fire they advanced forward “like a machine” in the words of one awed Tennessee captain. Though they, effectively, faced two divisions, they advanced into the teeth of enemy fire until Pickett was able to reorganize his men and countercharged.

Sturgis was gravely wounded reorganizing his flank, and his division fell into disorder. Grover’s men were forced to fall back ingloriously from the Confederate earthworks…

By 2pm, once the lines had stabilized, the whole Louisiana brigade had suffered 746 men killed or wounded, taking 40% casualties with Wheat himself suffering his third wound of the war. The heaviest casualties of any brigade engaged on that day, but the line held…” - Pipe Creek: The Bloody Day, William Westmorland, Philadelphia Press, 1989

The stand of the Louisiana Tigers was the only thing which held Lee's army together at Pipe Creek

“Hancock had led the men in a flanking march beginning early in the day, supported by Pleasanton’s cavalry in full expectation that he would be able to move unobserved on the Confederate flank. However, unknown to the whole of the Union army, Lee’s scouts and lookouts were able to confirm the movement early in the morning, and support was moving to the right flank even as Hancock marched.

Blissfully unaware of this development, Hancock marched up Hanover Pike towards Manchester, his infantry leading, with the cavalry in the rear ready to exploit a breakthrough. Hancock was pleased to be leading his men against the extreme end of Lee’s line, pleased to not be thrown against earthworks like he had been in June. “I was pleased to not order the boys in and over once again. I hoped to face them on equal ground.”

Coming on the Confederate lines at Dug Hill near Manchester, Hancock found, as expected, the thin line manned only by dismounted infantry. However, as he maneuvered his men into position, he was unaware that Hood’s division was maneuvering to meet him.” - Hancock the Superb: The Life of Winfield Scott Hancock, Charles Rivers, Newton Publishing, 2012

“Pope’s great flanking attack, perceived as the great strategic end, was stymied as Hancock’s men deployed for battle. Initially buoyed by the apparent lack of Confederate forces, the two infantry divisions marched for the hill making the Confederate flank.

Stoughton’s 1st Division would be on the receiving end of Hood’s initial assault. Hood, his beloved Texans leading, brought his forces to bear just as the men of 1st Division came to grapple with the Confederate line. The shock of this unexpected contact briefly unnerved the Union men, but they pitched in again with aplomb, but they could not move the now one armed Texan general. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalrymen, mounted and dismounted, supported with their rifles and carbines, stymying Hancock’s attack. The mounted men skirmished with his flank, forcing Pleasonton’s division out of the line of battle…

At 2pm Hancock rallied his men, sending them in once more, but they failed to drive home the attack. His divisions were “used up” he would opine to his wife. The men had fought too hard for too long, and could not drive the attack home.

This phenomenon was happening all across the Union lines. Men would rush to the attack and hurl themselves down, engaging in pointless firefights. Though their officers would drive them on, the sight of the entrenchments seemed to have a queer effect on the men. Even Kearny’s brave soldiers, instead of continuing their attack, fought tenaciously to hold their ground on Mahone’s Hill. Though Kearny fought hard, the failure of the grand attack up the center, coupled with Meade’s indecisive push on the flank, allowed Lee to free up Jones’s division to help drive the Federals back.

In a hard fought action, the Confederates at last drove Kearny off the hill, and he would withdraw ingloriously across Pipe Creek at 4pm…

With the day drawing on, and Pope learning of the failure on his left from Hancock’s attacks, he hesitated. Hooker and Meade all advised a withdrawal, each convinced that Lee would attack on the morrow. It had been what had happened at Island No. 10 in 1862, and in his advance on Grenada in 1863. Fatally, Pope hesitated. He did not know enough of Lee’s dispositions, and he was now afraid he had been misled. Had Jackson really left? Or was he making his way back, even now, to Lee’s lines. That indecision kept him awake the night of September 1st, but at 1am, he gathered his commanders in a council of war.

Did they believe Lee could counterattack come the morning? All save Hancock believed this to be so, and even Hancock went on record stating he disagreed with the consensus. Hooker, Ord, and Couch agreed that Lee would most likely counterattack first thing in the morning. Meade was the only general not to proffer his opinion, which would be further used against him in later life.

Pope took these counsels to heart, and ordered that the army begin withdrawing, leaving the wounded who could not be moved easily…

On the morning of September 2nd, Lee’s battered forces braced for another day of fighting. As the day wore on however, they looked out across the creek and saw, not a vast Union host ready to fight, but the signs of a hasty withdrawal. The only men left were the wounded and some soldiers so exhausted they had slept through the whole night and awoken to Confederate captivity.

Lee removed his hat and, at least according to one Lt. Peterkin, praised God for victory that day…

In the Battle of Pipe Creek, Lee had lost 9,717 men killed wounded or captured. Nearly a quarter of the force he had brought to the field that day. Pope meanwhile, had lost 15,462 men killed or wounded. It was a victory, but a victory of a sort. Lee sardonically noted “Many more victories such as these, and our army is ruined!”

The next day, he would begin his withdrawal towards Virginia, while Pope’s forces would shadow his retreat beginning September 6th, giving Lee three days to move unmolested. Lee had won his victory, not where he had liked, but the Army of the Potomac had once again come away with a bloody nose…” - Pipe Creek: The Bloody Day, William Westmorland, Philadelphia Press, 1989

-x-x-x-x-

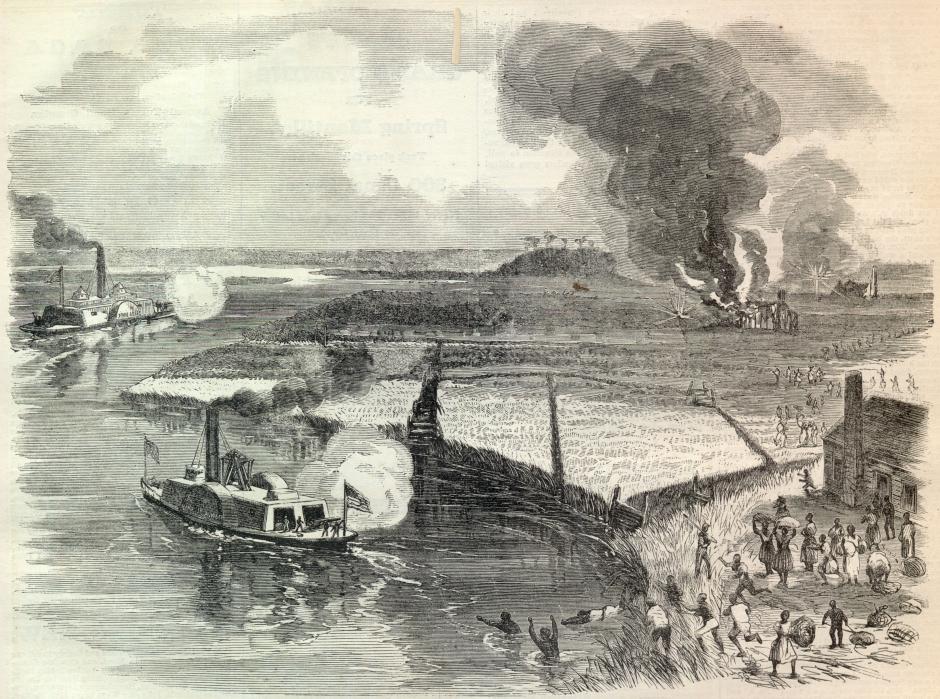

Annapolis and environs

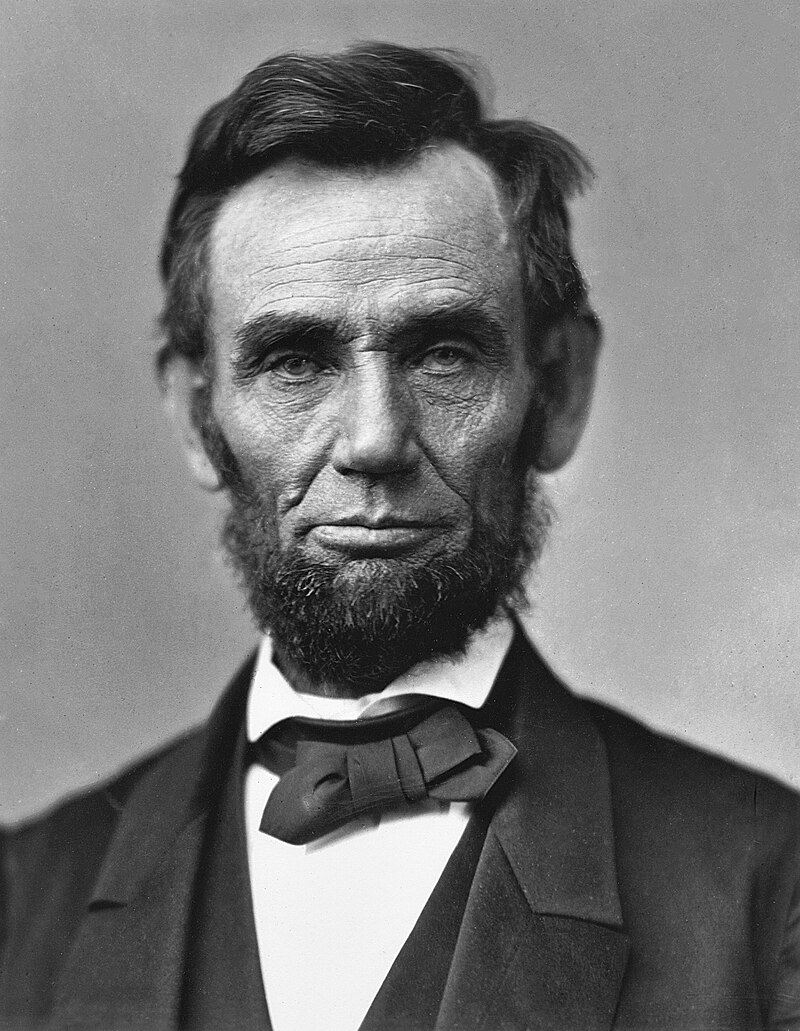

“Through the end of 1863 and well into 1864, the presence of Confederate troops at Annapolis and Annapolis Junction presented a direct threat to Washington. The fear that the Confederates could or would cut the only rail line to the capital and the battlefields south of it kept Union officers up at night. Lincoln himself realized that it was a national embarrassment for the Confederacy to not only occupy a state capital, but to present such a clear and present danger to the national capital itself despite the breaking of the siege.

Lincoln was well aware that he needed to show a strong political front in 1864, and with the conventions of summer giving away to the general campaigning of fall, Lincoln was under immense pressure to prove to the whole of the nation the Republican resolve to win the war. The Confederate threat to the capital had to be extinguished.

To that end, the troops streaming south from Canada and New England were to be formed into a new army whose task was to crush the Confederate toehold in Maryland.

Leading this new Army of Severn would be the same man who had won such acclaim last fall in the victory at Saratoga, Ambrose Burnside. His now much reduced Army of the Hudson (in reality only the XVII Corps) would be augmented by Erasmus D. Keyes XXI Corps or the former Army of New England. These forces had cut their teeth against British regulars, and Burnside considered his own troops at least to be the equal of anything the Confederacy - or any European army in his estimation - could throw at them. In total, he had been given command of 28,000 men to protect the capital from any threat, and just as importantly, hem in a major Confederate force.

Army of the Severn: Ambrose Burnside

XVII Corps (Silas Casey)

1st Division William Wallace Burns, 2nd Division, Francis C. Barlow

XXI Corps (Daniel Sickles)

1st Division John J. Peck, 2nd Division Erasmus D. Keyes

Siege Artillery (Henry L. Abbot)

Whiting’s Fourth Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, had been installed in Annapolis for just over a year. From its lofty beginnings with four divisions strong and a strength of 36,000 men as the “Army of the Chesapeake” in the heady days of 1863, it had dwindled to a mere 14,000 men in two divisions. With artillery and a cavalry brigade, the whole enterprise numbered just over 16,000 men.

Fourth Corps: Army of Northern Virginia: William H. C. Whiting

Holmes Division

Branch’s, Wise’s and Manning’s brigades

Ransoms’s Division

Ransom’s, Evan’s and Hagood’s brigades

Beverly H. Robertson’s Cavalry Brigade[3]

1st Maryland, 4th North Carolina, 5th North Carolina

Whiting however, had not been idle. He had been meticulous in constructing fortifications for his men just north of Annapolis. Digging into the rough and rocky country of the Anne Arundel, he extended his pickets as far as Crownsville, making it a focal point for raids against the rail line. His men secured their lines on the Saltworks Creek and Gingerville Creek well supported by heavy guns and the naval guns of Buchanan’s Home Squadron[4]. Stretching four miles, the double lines of trenches, abatis, and rifle pits covered all conceivable approaches to Annapolis, bristling with guns. It was on these lines he would make his stand…

The weakness of the Army of Severn was that it had never before worked together. While Burnside’s former corps was all veterans of the hard and often desperate fighting against the British, Sickle’s men - formerly Keyes[5] - had not seen combat beyond skirmishes since August of 1862, and by 1864 many suspected they had “lost their edge” having instead sat in fortified posts and observed their British foes. The men of XVII had fought in Canada and New York, well earning their veteran status, but with regiments in many instances reduced to a mere 200 or 300 men. The smaller corps was aided by Keyes larger formations, but this was not apparent.

Sickles made matters no better, and quarreled with Casey over seniority. Burnside, to his credit, squashed any attempt by his subordinates to whip up discord. “We are fighting here for a national redemption,” he would admonish the proud Sickles. “The eyes of the nation are upon us, and we had best play our parts.”

To that end he prepared his men as best he could, engaging in running attacks that drove the Confederate forces back from Crownsville and into their lines north of Annapolis. However, Whiting simply dug in and dared Burnside to attack him. Burnside, having learned much from his time fighting in New York, knew he would incur terrible casualties attacking the Confederate lines, and intended to develop a regular siege of Annapolis, and he set about doing so on September 2nd…

While the Siege of Annapolis was ongoing, with Whiting’s forces blocked up in the state capital, Lincoln at last began to move the machinery of the nation back to Washington. With the Confederate threat locked up tight, or in Lee’s case, far away, he felt secure in the knowledge Washington could hold against any threat.

It was the knowledge that Washington was secure which would lead Lincoln to issue one of the most cutthroat orders of his career. Needing a victory, he demanded Burnside attack Annapolis. When Burnside protested, claiming a siege would eventually starve the Confederates out, he was reminded that the Confederate fleet was providing all the supplies Whiting’s men would need. Burnside continued a correspondence from September 5th to 11th begging Lincoln not to order an attack, until he was bluntly informed the attack must go in for good or for ill, or the command would be handed over to someone who would order the assault.

Unwilling to die on that particular hill, Burnside ordered his men to assault Annapolis on September 17th.

As the sun rose, a cool ocean breeze flowing through the sky, Burnside had a great bombardment of siege guns commence. Lasting from 6am to 8am, he hoped that such an attack would keep Confederate heads down and, at the very least, provide some relief to the men charging into the prepared works ahead. Unfortunately, the Confederate guns were just as well shielded, and they answered back, engaging in a general artillery duel. The significance of which could not be missed to the defending Confederates.

Waiting until the bugles and drums of the approaching Union columns sounded, the Confederates had huddled in their trenches. At that signal, captains shouted and sergeants hurried men forward, and they braced themselves for the coming attack.

The unfortunate victims of this preparedness would be the men of Barlow’s division. Barlow had, to the best of his ability, prepared his men. In a great mass of regiments, he led them forward at the double quick, not a man firing as they charged. The Confederates replied with shot and shell, shredding Barlow’s men, and wounding Barlow himself, but on they came. It was a testament to discipline that the attack did not break, but they surged into the first Confederate lines, and to the surprise of all, managed a toehold.

Two bloody hours of fighting followed as Peck’s men attempted to exploit this breakthrough. However, the Confederates under Hagood soon counterattacked, and despite Peck’s intervention, Barlow’s men were driven back, suffering twenty percent casualties, but having earned the praise of the army by making a toehold in the first place…

Burnside would write of the days events, praising the men, but informing Lincoln that absent more men, and more naval support, he could not budge the Confederate line. Buchanan’s mortar rafts had extracted as steep a toll as Whiting’s guns…

Despite this bloody repulse, Lincoln was pleased with the demonstration. The nation now knew that the Confederates in Annapolis posed no threat to either Washington or Baltimore. Lincoln reasoned that “corking them up” at Annapolis would serve as much purpose as forcing their surrender. However, the partisan press portrayed it as either a strategic victory, or a great failure. The New York World would lament “800 dead and 2,000 crippled to satisfy Lincoln’s ambition!” inflating the casualties by over a thousand. The election was going to influence the fighting as much as the facts on the ground…” - Annapolis in the Great American War, Phillp Mifflin, United States Naval Academy, 1989

-----

1] The exact strength of Pope’s army at Pipe Creek will be hotly debated by historians TTL.

2] After three years of both hard fighting and hard living, this “Special Battalion” is more a series of companies/penal battalion than a proper battalion. “An Army of Thieves and Worse” would about describe them.

3] This was originally Imboden’s brigade, but he was removed to the Valley in early 1864 to command the cavalry there.

4] The Virginia(10)[F], South Carolina(10), CSS Leonidas Polk(3), CSS Lafayette(3), North Carolina(2), Missouri(2), Florida(9), CSS Alabama(8), CSS Texas(9), CSS Rappahannock(6), CSS Monocacy(6), Shenandoah(11), Raleigh(2), Beaufort(1), Teaser(2), Hampton(2) and a dozen mortar boats.

5] Keyes force was, essentially, the VI Corps of the Union Army. That formation was dissolved to create the new force for the Army of the Severn.