China and Central Asia - 1759 to 1783

Natural Frontiers? The Limits of Chinese Expansion in the 18th Century

The Qing Campaign against the Dzungar Khanate was known as one of the “Ten Great Campaigns”, one of the Emperor Qianlong’s wars that had expanded the glory of the Qing dynasty and secured the borders of China against restless nomadic peoples. However, like the later war with Burma, the campaign was not the unqualified success that had been claimed by Qing propaganda. Although the Dzungars were eventually defeated and destroyed as a people by Chinese forces, the war had been a difficult one. The Dzungars were for a time allied with Afsharid Iran, who had swiftly recovered from collapse two decades previously and who had, like the Qing, established an empire whose borders were far more extensive than those of the previous dynasty. Nader Shah, the first of the Afsharid Shahs, was an immensely ambitious individual who had it in mind to emulate the last of the great Nomadic Leaders, Timur. By the late 1750s, his successes in Central Asia had emboldened him, and he began to draw up plans to emulate Timur’s unfinished conquest of China.

Nader saw potential allies in the Dzungars and the Khalka Mongols, both of whom were engaged in a bitter struggle with the Chinese. Nader’s plan to conquer China was impractical even with the help of these allies and his own considerable resources, but Iranian intervention into the war nevertheless threatened to complicate the war significantly. Were the Iranians to prevent the destruction of the Dzungars, they would prove to be a threat to China’s security for years to come. Although the Chinese saw success against the Dzungars, their initial encounters with the Iranians were not promising, and they suffered a heavy defeat at Bishkek in the summer of 1758. It seemed as though Iranian forces were strong enough to push back the Chinese, though their forces in the region were saved by the assassination of the Iranian ruler Nader Shah. His successor had far more pressing concerns at home, and swiftly signed a favourable peace with China that established a border and allowed China a free hand to destroy the Dzungars, though with the promise to respect the rights of Muslim cities in the Tarim Basin.

While some of the Dzungars escaped into Iranian territory (where a number served as mercenaries in Reza Shah’s army), the majority were left powerless in the face of a renewed Chinese onslaught. The downfall of the Dzungars was bloody, but it left China’s presence in the West assured with no challenges from nomadic peoples. China’s control of the area was confirmed as the Iranians, more focused on internal challenges, neglected to aid the Muslims of the Tarim Basin in a rebellion against Qing authority which took place in the late 1760s. Though relations between the Afsharids and the Qing were never warm, the two seemed to have at least an understanding, preferring not to exhaust themselves in wars that promised little reward far away from home. It would be this understanding between the two powers that would provide the basis for Iranian-Chinese relations and interaction for many decades to come.

In Southeast Asia however, challenges to Qing expansion were more persistent. Attempts from the Burmese to extract tribute from Shan States that were tributaries of China led to all-out war between China and the Burmese. There were no convenient deaths to provide China an easy end to the war, and after 7 gruelling years of struggle, including a number of failed invasions of Burma, the Chinese were ultimately forced to acquiesce to the Burmese ruler Hsinbyushin. For a war that was intended to showcase China’s strength after an uneven performance against the Iranians in the West, it was a complete humiliation, and demonstrated the ecological unsuitability of extending the Chinese empire further south [1]. Subsequent attempts by the Qianlong Emperor to punish Burma by a commercial embargo floundered on the unwillingness of merchants in Southern China to stop the trade in goods such as Burmese Gems. It would not be until the abdication of the Qianlong Emperor in 1796 that the embargo was lifted, officially due to the requirement of Burmese cotton in Yunnan.

It were these two struggles more than any other that demonstrated the geographic limits of Qing rule. Whether it was the political/logistical barrier presented on the Western border with Iran, or the political/ecological barrier that had become apparent in the Burmese war, the last major campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign had seemingly demonstrated to the Chinese the “natural” limits of their Empire. This had little effect on Chinese political theory however, which was still fundamentally Sino-Centric. After all, Burma and even Iran were hardly the equal of China in economic or cultural terms. China may have had around 20 times the population of Iran, which does provide some credence to the Chinese view of things. Simply put, though China had suffered “reversals” in these wars, the propaganda of the Qianlong Emperor had proclaimed that he had secured all the borders he had needed to. Although the last of his “Great Campaigns” had been an unmitigated failure, the sheer scale and grandeur of the Chinese Empire at least allowed him to pretend otherwise.

[1] – The Chinese defeat has been more severe than her loss against the Burmese in OTL, partially as the Burmese have not fought a war simultaneously with Siam and have been able to concentrate their forces against China.

* * * * * *

The Chinese Diaspora in Iranian Central Asia

For Millennia, the trade routes that linked China to the West through Central Asia had been for the most part dominated by the nomadic peoples who lived in the area. However, with the coming of “Subcontinental Empires” in the 18th Century, these people were gradually brought under the imperial systems of China, Iran, and to a lesser extent Russia. Although the importance of land-borne trade had relatively declined for China as new trade-routes were opened by sea, the revival of Iran in the middle of the 18th century had opened up new markets for both Iranian and Chinese goods that were more easily accessed by the land route of the old Silk Road. As the threat of robbery, banditry and other threats to merchants gradually receded, goods such as spices and textiles made their way between the two empires. Initially, this trade was dominated by peoples such as the Uighurs, but from the 1770s onward it was increasingly common for ethnic Iranians as well as Han and Hui to be involved more directly in the trade.

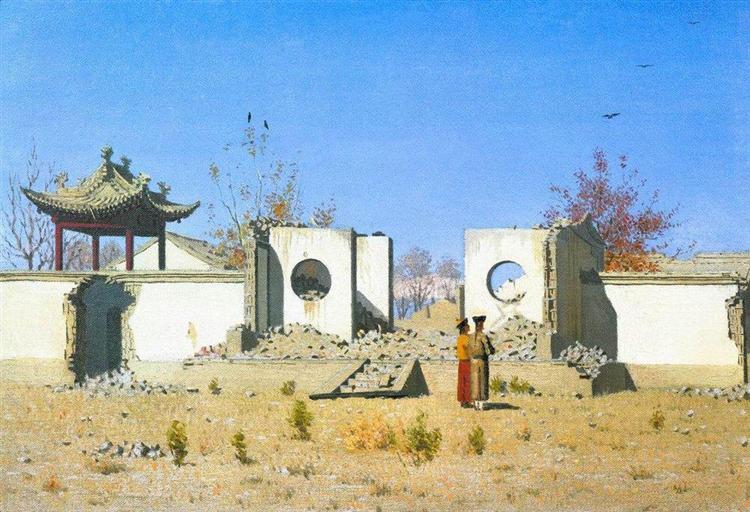

By the 1780s, small communities of merchants had sent themselves up in major cities of each empire. The small Chinese community of Mashhad remains the only one in Iran of which a considerable amount of documentary evidence remains. Initially numbering only a few families, the community had eventually grown to one of a few hundred which in 1788 was allowed to construct a small temple which can still be found in Mashhad’s Chinatown today. Despite being a diverse city, few of its inhabitants were considered to be as truly foreign as the Chinese, who were observed to be “stranger in manner and belief than the Dutch and English, though better groomed overall” as one Iranian novelist described them. And the Iranians generated a similar amount of interest in China. The majority of Iranian traders were located in the Southern port city of Guangzhou, the centre of trade for Southern China, though smaller communities were located in cities such as Lanzhou in the North as well. While the object of some suspicion, the Iranians seem to be held in a higher regard than Europeans, at least when memories of the Sino-Iranian war of the 1750s was gradually forgotten.

Despite the growth in trade that had taken place between Iran and China in the late 18th century, both were still relatively unimportant to the other. For Iran, markets in India and Europe were closer and more important, and China’s trade with Southeast Asia and Europe remained more important than her trade with Iran. However, trade between the two nations remained the basis for peace through the period, and enabled a significant amount of cultural intercourse between the two. Most famously, the Iranian Shah Shahrukh reportedly greatly enjoyed a Chinese meal that he had eaten at a court celebration in 1785. There is less evidence, however, that elements of Iranian culture had penetrated the Qing court in China. Certainly, what scraps of evidence concern the Chinese court’s perception of Iran mirrored Chinese perceptions of other areas of the world, namely that nothing they could produce would be of interest to China.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - There haven't been a great deal of changes in China proper as of yet, but it would feel like a bit of a cop-out not to do something on what is different in China so far. The fact that there is a fairly stable border between China and Iran will definitely have its effects on both, though this will be true of Iran more than China, for the simple fact that China is so much bigger, and its core lands are so much further than Iran's. The last free nomadic peoples of Central Asia are now mostly Kazakh, and it seems like only a matter of time before they too will come under the rule of their settled neighbours.

And yes, a Chinese presence in Iran will surely lead to some interesting culinary innovations and fusions in the future.