So we come at last to the final post for Part-IV of...

Part IV Post#11: End of an Era

The early 1980s marked a watershed period in spaceflight, as both the nature of and participants in space travel began to shift. One of the most visible manifestations of this change was the end of what was retrospectively dubbed as the “First Space Race”. This point is often dated in the public mind at the joint Dynasoar-Chasovoy mission which concluded 1981, but the first phase of manned spaceflight could more accurately considered to have ended in 1982. Though the triggers for these shifts were complex and deeply rooted, for many people they became associated with the changes in leadership that had occurred in both the USA and USSR during 1981.

The election year of 1980 was a time of turmoil in American politics. The Oil Shock and subsequent collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1974 had triggered a period of so-called “stagflation”, the reversal of which had been one of the key objectives of the Rockefeller administration. In this they had some success, managing to stabilise the value of the dollar and bringing the country out of recession in 1977, but the growth that followed remained stubbornly slow. With government expenditure holding steady, or even increasing in the hope of stimulating the economy, America’s deficit continued to grow.

The sluggish economic recovery underlined a wider loss of confidence in America. The reduction of tensions with the Soviets was generally welcomed, but the apparent success of Kirilenko in re-invigorating the Soviet economy only made the contrast with America more stark. The intervention in Iran was generally supported by the public, but a vocal minority grabbed headlines in a growing number of anti-war protests, claiming that the action had less to do with protecting civilians from terrorism than protecting a corrupt allied leader and Western oil and gas interests. With the Gibney scandal undermining what little faith the public still had in the integrity of its leaders, the 1980 elections had the feeling of a turning point.

With the Republican party caught off-balance by the late withdrawal of President Rockefeller from the running, potential candidates had less time to organise. The party finally chose to put forward Vice President Daniel Evans as their candidate, following a strong challenge from Senator Ronald Reagan. Although Reagan’s supply-side economic platform was becoming increasingly fashionable amongst economists, his strong rhetoric against improved relations with the Soviets worried some, whilst others pointed to his lack of executive experience and his age (Reagan would be the oldest president in US history if elected). This tilted the balance towards Evans, who was able to walk the line of taking credit for the Rockefeller administration’s achievements whilst distancing himself from the President’s moral failings.

Ironically, many of the economic policies put forward by Reagan were similar to the positions adopted by the Democratic candidates, the most vocal of whom was William Proxmire. Elected to the Senate in 1957, Proxmire had made a name for himself in opposing wasteful government spending, seeing a profligate expenditure as one of the root causes of America’s economic woes. Indeed, his vocal opposition to “pork barrel” politics had earned him enemies both amongst Republicans and within his own party, as with his loud and repeated opposition to President Muskie’s Columbia project. In the end it was this (along with his pledge to refuse to accept campaign donations) that scuppered his chances of being selected. Despite some early successes with his public campaigning, he’d burned too many bridges, and the support he needed from the party machine was simply not present.

Despite Proxmire’s withdrawal from the race, his message on the necessity of cutting back on wasteful spending and reducing the size of the federal government had struck a chord, and were incorporated (in a watered-down version) into the campaign of the eventual candidate, Frank Church. This won Church the support of Proxmire, but he also gained endorsements from a number of establishment Democrats, including the Kennedys - though how much value this had was much debated, given the Kennedy name had become synonymous with election defeats. Despite jokes about Church having been given “the Kennedy curse”, he went on to soundly beat Evans at the polls in November, gaining a clear a mandate to reform the national finances and reduce waste.

The change in leadership in the USA was soon echoed in the USSR, as Andrei Kirilenko made the surprise announcement in March 1981 that he planned to step down from both his role as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (which had latterly been styled, inaccurately, as “President of the USSR” in the foreign press) and the leadership of the Party. Publically, Kirilenko stated that he wished to ensure the continuing vigour of the national leadership by allowing fresh blood to come through the ranks. Whilst this may well have been true in part, his decision to step down was undoubtedly influenced by his worsening health, as he slowly succumbed to arteriosclerosis. His illness was known of only at the highest levels of Soviet leadership, and so far had not seriously impacted his ability to work, but Kirilenko felt that it would be better to have a managed handover of power whilst he was still fit enough to influence events rather than risk the sort of chaos that had followed Shelepin’s death.

The outgoing First Secretary’s call for new blood notwithstanding, it had been clear for some time that Premier Maxim Teplov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers and long term confident of Kirilenko, was the heir apparent, and indeed Teplov was duly elected President of the Supreme Soviet in March 1982. A few weeks later, on Kirilenko’s recommendation, he was also elevated to the post of First Secretary of the Central Committee, consolidating his position at the top of both the Party and the State. Replacing Teplov at the Council of Ministers as Premier was Boris Gostev, a Belarusian economist who had been an early supporter of Kilirenko’s and Teplov’s Khozraschyot reforms. This marked the first voluntary transition of power at the top of the USSR since the creation of the state in 1922.

Even as Teplov rose to the commanding heights of the Soviet state, the reforms that he had helped to spearhead as Premier were coming under increasing scrutiny. The economic growth experienced in the Soviet Union since 1976 had been largely based upon extractive industries, especially an expansion in oil and gas exports following the 1970s Oil Shock. The gradual opening of Western markets to Soviet exports, as well as the reforms to the pricing of energy sales to Eastern Europe, had enabled to USSR to tap into this rich revenue stream, and the economy was given an extra boost from the turmoil in the Middle East after 1979, reaching a peak during the attempted Saudi coup of 1981. However, this influx of petrodollars had served only to paper over the cracks in the Soviet system, not fix them. It had given an illusion of effectiveness to the Khozraschyot reforms, when the reality was that the attempt to mimic market values in the Soviet economy had only served to add one more layer of deception. The “real economic values” assigned to production by Gosplan were based on unreliable inputs from factory managers, and in any case were unable to keep up with the real demand in the economy. A real expansion of the civilian economy did take place as resources were shifted away from the military, but the increased volume of consumer goods wasn’t matched by any increase in quality, and productivity continued to stagnate, or even decline, as the system failed to provide incentives to modernise production or develop new techniques. By 1982, as world oil prices began what would turn into a sustained fall, the inefficiencies of the Soviet economy threatened to become visible for all to see.

So it was that the new leaders of both Superpowers found themselves looking to cut costs, with spending on space being one of the areas to come under scrutiny.

August 1982 saw the decommissioning of the Chasovoy-3 space station after five years of service, bringing manned Glavkosmos missions to a halt pending the launch of their new, modular Yedinstvo space station, the first component of which was expected to be ready in 1984. The final mission to Chasovoy also marked the last flight for the venerable Zarya spacecraft, as the versatile two-seat capsule was slated to be replaced by a more capable three-man spacecraft loosely based upon Chelomei’s Safir moonship. Named “Yantar”, the design was optimised for its role as a space station ferry, including an unmanned version for bringing up supplies. Plans had been in place to launch Chasovoy-4, a copy of the Chasovoy-3 design, as an interim station to ensure the continuation of manned space missions, but Kramarov eventually decided that, in the absence of more funding, the diversion of resources to a stop-gap station would not be worthwhile. All effort was instead focussed on the new station and its support craft.

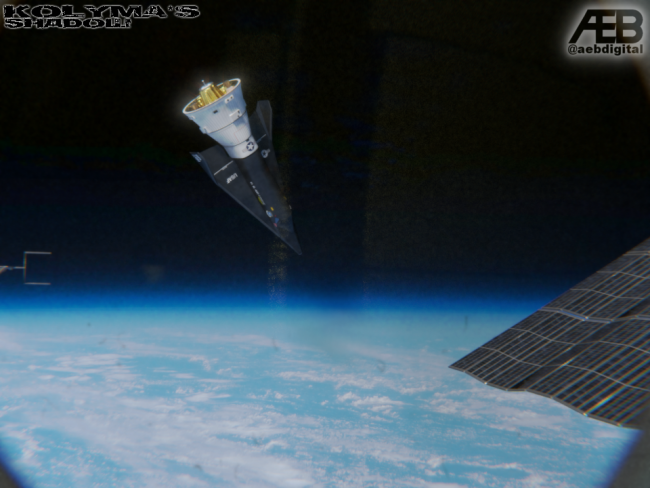

1982 also saw the final flight of the American Dynasoar, with

Tara performing one last spysat servicing mission on DS-36 in September 1982. With the Shuttlecraft now not slated to begin air-drop test flights at Edwards AFB until 1983, and a first orbital launch not expected before 1986, the Air Force had originally planned to keep the Dynasoars flying until their replacement was commissioned. However, the cuts to Federal spending that had accompanied the arrival of President Church at the White House soon changed these plans. Faced with the need to trim spending to reduce the national deficit, the Air Force had been forced to downsize its planned Shuttlecraft fleet from four to two orbiters operating from a single 747 carrier vehicle, and even then had had to sacrifice ongoing Dynasoar operations to ensure continued funding for the Shuttlecraft. With NACAA’s lunar ambitions on indefinite hold (despite repeated political endorsement of a Moon landing as a “horizon goal” for the agency), this meant that by the end of 1982 no nation on Earth had an active capability to put humans into space.

Last of the Dynasoars. The glider Tara

returns to Edwards AFB at the conclusion of mission DS-36, September 1982.

At the same time that crewed launch capability was disappearing, more and more organisations were gaining access to the benefits of unmanned access to space, most visibly through the increasing number of commercially available launch services. By the early 1980s, Europe’s Theseus rocket had established itself as a reliable and economical alternative to the USAF-operated Minerva for both government and commercial satellite launches. Operated under ESLA control, Theseus’ competitive pricing (thanks in no small part to considerable subsidies, both direct and indirect, from European governments) enabled it to capture 40% of the commercial launch market by 1982, necessitating the construction of a second launch pad at Kourou to keep up with demand. The continuing practice of prioritising military payloads for Minerva launch slots meant that, despite increased efforts at marketing Minerva for commercial users, Theseus was providing a welcome boost to launch capacity for US satellite operators, eating into the American market share as well as servicing its native European market.

This foreign encroachment on the American launch market began to reverse after 1982, when the new Liberty rocket came into operation. Although unable to meet Ford’s initial promise of halving launch costs, Liberty did come in around a third cheaper than Minerva, making it competitive with Theseus even without subsidies. Over the next three years Liberty became established as a significant player in commercial launch, winning back market share from ESLA. Ford’s emphasis on simple, modular rocket stages proved to be a winner not only in terms of streamlining production costs, but also in terms of reliability, as the common stages racked up flight-hours and the ground crews quickly gained experience without having to learn different procedures for each stage.

As the number of successful launches mounted, Ford’s competitors began looking for ways of incorporating Liberty’s lessons into their own developments. This appraisal was not just limited to the Atlantic nations: the Japanese government had been considering developing their own launch capability for some time, but their industry was not yet confident of having the necessary experience. The solution, agreed with the US government at the time of Liberty’s introduction in 1982, was to license-build a version of the American rocket adapted to Japan’s needs. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries would be the Japanese industrial partner, manufacturing rocket cores to Ford’s specifications. The engines would initially be built by Aerojet and imported by the Japanese, with a native-build version of Liberty’s AJ-200 rocket engine coming on-line around 1988. The STAR-48 upper stages would be imported for Thiokol directly, with Mitsubishi looking to develop a clean sheet liquid upper stage for their launcher by the early 1990s.

Despite these successes for Liberty, there remained voices arguing that it didn’t go far enough in reducing the cost of space launch. Some romantics pinned their hopes on the USAF Shuttlecraft to finally demonstrate the economic bounties of reusability, but there were others who revisited ideas previously dismissed by the government sector. Ideas which, if freed from the dead hand of government, may yet realise the full potential of affordable access to space and open the far frontier to humanity’s true pioneers; her entrepreneurs.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

“Doctor Kayser?”

Lutz Kayser, CEO and Chief Engineer of Orbital Transport and Rockets, looked up from his fight with the baggage trolley to see a tall, slim man walking towards him across the arrivals hall of Heathrow’s Terminal 3. The man wore an expensive-looking business suit and had a smooth, politician’s smile on his face.

“Yes?”

“I’m Martin Gilmore,” the man continued in a cultured British accent as Lutz took his hand. “We spoke on the phone yesterday. How was your flight?”

“Quite pleasant, thank-you,” Lutz replied, his own German accent mellowed by his years in Washington.

“Sorry we couldn’t fly you over on one of our own jets,” Gilmore went on as a second man in a chauffeur's uniform took Lutz’s suitcase and they headed for the exit. “So far we’re only running Heathrow to Idlewild. We’re planning a route into Miami for next year, but it could be a while before we get into Dulles. Still, I hear PanAm look after their SST passengers. Had you flown supersonic before?”

“Once, on the DC to LA route,” Lutz replied as the chauffer held open the door to a black Mercedes. “There are times when the greater speed can be of real benefit.”

“My boss would certainly agree with that sentiment!” Gilmore chuckled as he got into the seat next to Lutz. “He’s planning to have another run at the Blue Riband later in the year.”

“He enjoys a challenge.” It was a statement from Lutz rather than a question.

“You could say that, yes,” Gilmore replied with that stereotypical British understatement as the car pulled away into the London drizzle. “Of course, that’s one reason he’s so interested in your rocket system. Do you really think you can cut costs by a factor of ten?”

“Certainly,” Lutz replied. “At OTR we have been refining our designs for almost fifteen years. Our consultancy work on Liberty gave us a great deal of insight into many of the practical issues, and since then we’ve built and tested a number of prototypes for our pressure-fed rocket engine. We’re also supplying satellite control thrusters to both Ford and Hughes. I am confident in the skills of my team.”

“Forgive me Doctor Kayser, but I understand that OTR’s activities have always been as a subcontractor on a larger project primed by others, or small government R&D contracts. Are you sure you’d be able to manage something as detailed and complex as a full rocket development programme?”

“Mr. Gilmore,” Lutz replied with exaggerated patience, “we have designed our rocket to be as simple and easy to construct as humanly possible. There are hardly any mechanisms that can go wrong, and our engineering margins are large enough that there is no need for the type of precision fabrication used on other rockets. In addition, it requires very little ground support infrastructure and the rocket modules are easy to transport. In principle, any country possessing even a basic automotive industry could build our design.”

“Well, that’s reassuring, considering the state of the British Motor Company,” said Gilmore, wryly. “You know, usually we expect any new venture to show a return within one year of starting up. Assuming we signed on, how long would we be looking at before we could start suborbital flights?”

“I cannot commit to one year,” Lutz stated. “Two years should be possible though, with an orbital capability coming a year after that.”

“Two years,” Gilmore mused. “Nineteen Eighty-Seven. That should fit nicely.”

Lutz was puzzled. “I’m sorry, Mr. Gilmore, but fit nicely with what?”

Gilmore smiled. “Well, as you noted, my employer is a notorious thrill-seeker. He’s also very good at publicising his ventures, and in this case the two can be combined rather effectively. You see, after making his Atlantic crossing, for his next challenge he wants to take on an aviation record. He was planning a high-altitude balloon - we’ve got a special pressurised capsule for it already on order - but you, Doctor Kayser, may be able to give us something far more spectacular.”

Lutz stared at Gilmore in astonishment. Surely he couldn’t mean…

“How does that sound, Doctor? Your rocket making Richard Branson the world’s first private astronaut?”