The main reasons for this were twofold: firstly, US planners were consistently "behind the times" in terms of their assessments of Japanese strength assigned to the defense of Kyushu. This was the case right up until the end of the war - only by the middle of August did the picture become more clear, and even then, in D.M. Giangreco's words, it was still a "serious underestimate." Conversely - and this is seldom emphasized - Japanese planners overestimated the strength and capabilities of the Allied forces, such that there was a two-way intelligence gap. This cannot be repeated enough: Japanese military intelligence correctly predicted not only the timing and sequence of Allied operations, but also the approximate strength assigned to each. When they erred, they tended to be on the side of caution, anticipating greater forces than would be brought to bear against them and on an accelerated timetable. In plain language, the Japanese had "figured us out" and deprived the Allies of operational surprise, calibrating their defensive effort to repel an invasion much stronger than the one we actually planned.[1]

Given this, the forces and means the Americans and their allies assigned to Olympic were totally inadequate to assure victory, particularly air and ground forces. These facts can be readily discerned through superimposing the respective operational plans, OLYMPIC for the Americans and MUTSU-GO for the Japanese, on top of each other.

As we know from the failed raid on Dieppe, control of the air is co-equal with control of the sea for ensuring the success of a landing. Air supremacy, moreover, also frees up the naval forces to do their job against potential surface or undersea threats without worrying about enemy air attacks. I state the obvious here, because at Kyushu the Allies would NOT have possessed air supremacy. Excluding roughly 2,000 heavy bombers assigned to strategic duties, tactical air support for Olympic was to amount to 1,850 land based planes of General Kenney's FEAF based in the Ryukyus (excluding the 2nd Marine Air Wing) and 3,000 single engine planes aboard flat tops of the Third and Fifth Fleets, the latter of which included the British Pacific Fleet [2]. In other words, about 5,000 aircraft in total.

Against this, on the Japanese side, out of 12,684 aircraft of all types in the country as of August 1945, the "Ketsu" Operational plan called for at least 9,000 to be brought into the Kyushu battle as follows:[3]

- 140 for air reconnaissance to detect the approach of the Allied fleet

- 6,225 kamikazes and conventional bombers to target the assault shipping

- 2,000 "air superiority" fighters to occupy the opposing CAP

- 330 conventional bombers flown by elite pilots to attack the carrier task group

- 150 further conventional bombers flown by elite pilots for a night attack on the US escort ships

- 100 paratroops carriers inserting approximately 1,200 commandos at US airfields on Okinawa, inspired by the relative success of a small-scale sortie months earlier

The duration of all this was expected to be just 10 days. As can be seen, the Japanese would have possessed a numerical advantage of roughly 2 : 1 overall in tactical aircraft. Furthermore, if we consider that realistically only allied fighters matter in this comparison (bombers don't do CAP), then in fact the actual ratio would be about 4 : 1. Against such odds, American combat air patrol would be incapable of stopping the deluge of attacking planes, and the fleet would suffer enormous damage as a consequence.

IGHQ devised this plan based on an inventory of 8,500 serviceable aircraft in July 1945, to which it was hoped an additional 2,000 could be added by the time of the invasion.[4] Reserves of aviation fuel, though exceedingly scarce, were adequate to carry out the above plan: the strategic stockpile set apart for the decisive battle amounted to 190,000 barrels for the Army and 126,000 barrels for the Navy. By July 1945 the total inventory of aviation fuel in the Japanese mainland comprised 1,156,000 barrels. As a means of visualizing this in action, the entire three month period from April to June 1945 burned 604,000 barrels within Japan's inner zone, including the "Kikusui" operations at Okinawa. Despite this, consumption of fuel actually decreased 132,000 barrels from the previous quarter and 201,000 barrels from the one before that, owing to shortening distances. At Kyushu, the battlefield would be Japan itself, flight times would be short, and patterns of approach highly variable. As was the case in the Philippines, the mountainous coastline would protect attacking aircraft from being discovered on radar until they were very close to the invasion fleet.[5]

From the experience at Okinawa, the loss or expenditure of 1,430 bombers and kamikaze aircraft by the Japanese Army and Navy caused about 10,000 casualties, half of them deaths, to American and British forces, or about 7 casualties per Japanese aircraft committed. If, based on the above factors, the Japanese improved their performance at Kyushu, it could be expected that losses at sea could tally up to many tens of thousands, effectively crippling the US Sixth Army before it even got ashore. This alone would be enough to put the invasion in jeopardy, and it doesn't even take into account operations by remaining IJN fleet elements such as submarines, destroyers, or fast attack craft. Unfortunately, the situation that would have greeted the Sixth Army on the ground was nearly as bad.

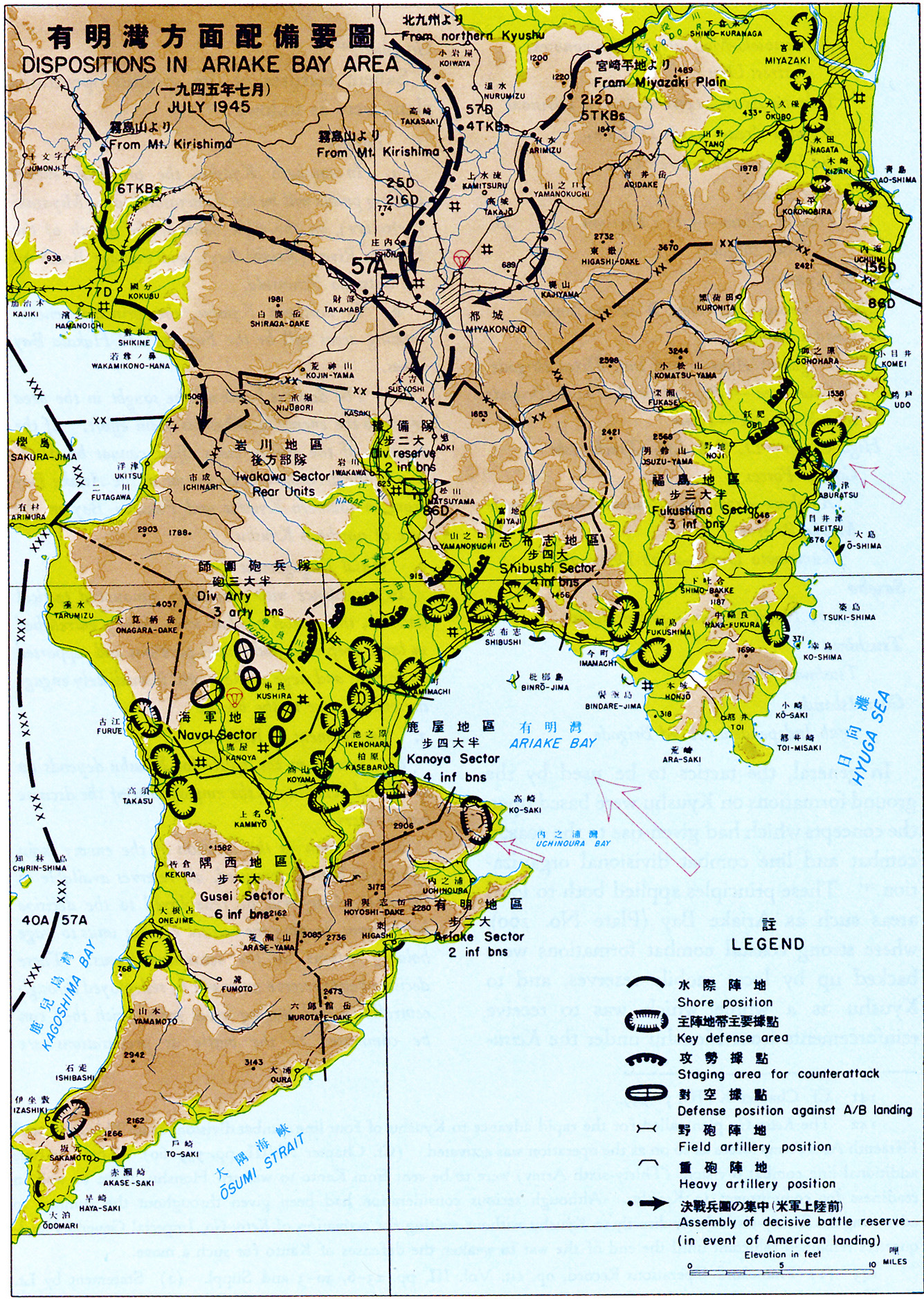

To oppose the 700,000 to 800,000 soldiers and Marines of the Sixth Army (of whom only about 600,000 would be actual "ground troops"), the Japanese Imperial Army planned to gather 900,000 men at the conclusion of their mobilization (already in its final stage), to be bolstered to 990,000 during the actual invasion through the transfer of 4 more divisions across the Shimonoseki strait from Chugoku. This does not even consider the large amount of Naval personnel present, who, as in the Philippines, Okinawa, and elsewhere, would have been inevitably pressed into service. As already mentioned, the topography of Japan and capabilities of the Allied forces meant that it was easy for IGHQ to guess the location, timing, and approximate strength of the expected Allied blows. Rather than the three-pronged flanking attack against only a portion of the Japanese Army anticipated by US planners, the Sixth Army was essentially going to make three frontal assaults straight into the teeth of an enemy that would have outnumbered it roughly 2 to 1 on the ground. The 57th Army in south-east Kyushu alone, for instance, comprised some 300,000 men, 2,000 vehicles, and 300 tanks.[12] By itself, this corresponds almost completely to what General MacArthur initially believed would be present in all of Kyushu by November 1945.

Unlike in other regions of Japan, the Sixteenth Area Army's preparations in Kyushu were well-progressed by the time of Japan's surrender in August: even though stocks of equipment and ammunition were strained by the rapid expansion of personnel strength, all forces were to be fully outfitted by October 1945 (and the Kanto Plain's Twelfth Area Army - by spring 1946)[11]. Because of this, American troops, badly battered by Japanese bombers before disembarkation at sea, would have landed ashore against an enemy fully expecting them and present in much greater strength than anticipated; indeed, in greater strength than had been previously encountered anywhere during the Pacific War. In the close-in, mountainous country, where US advantages in mobility and firepower are minimized, the combat would have taken on a savage, personal nature, conducted "at the distance a man can throw a grenade." Although "permanent" coastal fortifications were relatively sparse, there was no 'crust' to be broken (like with the German Atlantikwall), but a solid core spanning the entirety of southern Kyushu. American forces, who had no preconceptions of any of this, would have thrown themselves into a meat grinder. Even if they managed to overcome the initial defenses and withstand the enemy's counterattacks, the presence of Japanese forces dug into the mountains of northern Kyushu would have presented a constant danger through to the end of hostilities, as was the case in Italy and Korea.

There is one more important factor to consider: the weather. As mentioned previously, Typhoon Louise was set to batter the staging grounds on Okinawa in October, scarcely a month before the planned invasion. The damage done by this was estimated to set the landings, originally scheduled for 1 November, back to December at the earliest, which would not only have required a whole new analysis of weather and other environmental conditions but also would have afforded General Yokoyama's defenders even more precious time to prepare. Incalculable too would have been the psychological boost to the Japanese as a whole at the sight of the "divine winds" coming to their aid once again, and the damages done as a result of fighting elsewhere in Asia and by Japanese atrocities against civilians and prisoners of war (POWs). Further storms in the spring of 1946 (Typhoon Barbara) would have presented additional challenges.

In other words, to restate Major Arens' conclusion earlier in this thread:

"The intelligence estimates of the Japanese forces and their capabilities on Kyushu, for Operation Olympic, were so inaccurate that an amphibious assault by the V Amphibious Corps would have failed ... If Operation Olympic had been executed, as planned, on 1 November 1945, it would have been the largest bloodbath in American history. Although American forces had superior fire power and were better trained and equipped than the Japanese soldier, the close-in, fanatical combat between infantrymen would have been devastating to both sides."

I emphasize again, there is no credible scholarship anywhere in the world who can seriously claim that an invasion of mainland Japan would have been anything short of a catastrophe; a savage climax to the most horrible of all man's wars. It would not have been easy, far from it, and its ramifications would have undoubtedly lent themselves to the creation of a world radically different from the one we see today.

Some tables ---

Table 1: Japanese estimate of Allied air strength and the planned reality, July 1945[6]

Jap Estimate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Allied Plan

Land Based . . . . . 6,000* . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,000

Carrier " . . 3,300-3,800* . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,000

* Estimate for land-based craft: 1,500 B-29, 1,400 other heavy bombers, 1,100 medium bombers, 2,000 fighters

* Estimate for carrier-based craft: 2,600 to 3,100 USN and 700 RN

Table 2: Japanese estimate of Allied invasion fleet and planned reality, July 1945[7][8]

Jap Estimate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Allied Plan

USN

Carriers (all types). . 50 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

Battleships . . . . . . . 21 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Cruisers . . . . . . . . . 54 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .52

DDs and DEs . . . . . 330 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .442

RN

Carriers (all types). . 13 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

Battleships . . . . . . . . 4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . n/a

Cruisers . . . . . . . . . . 8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . n/a

DDs and DEs . . . . . . 40. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . n/a

Table 3: Japanese estimate of Allied ground forces and planned reality, July 1945[9][10]

Jap Estimate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Allied Plan

Kyushu . . . . . . . 15-40 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

Honshu . . . . . . . 30-50 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38-40

Figure: Japanese dispositions and counterattack plan for Ariake Bay, 57th Army

[1] - Giangreco p. xx

[2] - Allen and Polmar p. 299, Skates p. 170, Sutherland p.9

[3] - JM-85 pp. 19-21

[4] - Reports of Gen. MacArthur vol. 2. ch.2 note 100

[5] - Giangreco p. 80

[6] - Reports of Gen. MacArthur vol. 2 part.2 ch.19 p. 639, notes 101 and 102

[7] - same as above

[8] - Sutherland p.9

[9] - Giangreco p. 82, Homeland Operations Record p. 75, 82

[10] - Reports of Gen. MacArthur, JM-85

[11] - "Olympic vs Ketsu-Go" Marine Corps Gazette 1965

[12] - Drea "In service of the Emperor" p. 148