After having David Zabecki's book on the Spring Offensives i've found that some generals advocated for a divisionarry attack on Verdun. If this was launched waht would be the results?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Verdun in the Spring Offensives

- Thread starter The Moroccan Emperor

- Start date

I'm not a great historian of the Western front. Are you talking about the offensives the Germans launched in Spring 1918?

The big disadvantage of Verdun as an objective is that there's nothing strategically vital in or behind it. Verdun isn't a transit hub, nor is it a big population or industrial center, not is any of the above immediately threatened if Verdun falls. The main direct strategic benefit to Germany of taking Verdun, apart from morale effects, is that doing so would shorten the front, but shortening the front works both ways, and in Spring 1918 Germany has more manpower on the Western Front than the Entente so shortening the front probably helps the Entente more than Germany by reducing Germany's relative advantage in available forces for offensives or defensive reserves. Moreover, shortening the front by reducing a salient would leave Germany in the position of having to haul supplies and reinforcements through the fought-over grounds, so if Germany wanted to shorten the front they could do more advantageously by abandoning the adjacent St. Mihiel salient instead.

Verdun's disadvantages as a real objective also weaken its value as a diversion. If the Entente commanders have to choose between holding Verdun and holding Amiens or Hazebrouke, they're choosing the vital logistics hubs every time: losing Verdun would be an embarrassment and a nasty blow to morale, but losing the latter would cut off big chunks of the front from the rail network (requiring a large-scale withdrawal and possibly abandoning a bunch of heavy artillery) and open up Paris or the Channel Ports to follow-up offensives.

The other big problem with a diversion is that Germany's ability to simultaneously mount a convincing diversion and prepare a serious offensive to take advantage of it was questionable. The Spring Offensives relied on a single body of units for each major offensive operation, particularly the heavy artillery and the elite "stormtrooper" infantry that would lead the assaults. This is a big part of why the Spring Offensives petered out OTL (the same striking force was used over and over again, taking casualties and building up fatigue each time), and why Second Marne in particular was so devastating (Foch correctly anticipated the next strike and prepared a counteroffensive that succeeded in badly maiming the infantry portion of the striking force and capturing a bunch of the artillery). The same striking force would have a hard time threatening Verdun without also diluting its capabilities for the real offensive.

Where an attack at Verdun could be useful would be if Germany could pinch off the salient, encircling and capturing the defenders, instead of pushing into the shoulders of the salient like in the 1915 battle. This more or less mirrors the OTL American battle plan against the St. Mihiel salient later in 1918. A successful encirclement (or a hasty withdrawal to escape the closing pincers) could inflict a massively favorable casualty ratio (as at St. Mihiel, where the American and French forces took 15k prisoners, captured 450 artillery pieces, and inflicting 7500 KIA/WIA in exchange for taking about 7k casualties themselves). Threatening such an encirclement could be an effective diversion, if the German Army could sell it as a serious threat without too badly diluting resources from the real offensive.

Verdun's disadvantages as a real objective also weaken its value as a diversion. If the Entente commanders have to choose between holding Verdun and holding Amiens or Hazebrouke, they're choosing the vital logistics hubs every time: losing Verdun would be an embarrassment and a nasty blow to morale, but losing the latter would cut off big chunks of the front from the rail network (requiring a large-scale withdrawal and possibly abandoning a bunch of heavy artillery) and open up Paris or the Channel Ports to follow-up offensives.

The other big problem with a diversion is that Germany's ability to simultaneously mount a convincing diversion and prepare a serious offensive to take advantage of it was questionable. The Spring Offensives relied on a single body of units for each major offensive operation, particularly the heavy artillery and the elite "stormtrooper" infantry that would lead the assaults. This is a big part of why the Spring Offensives petered out OTL (the same striking force was used over and over again, taking casualties and building up fatigue each time), and why Second Marne in particular was so devastating (Foch correctly anticipated the next strike and prepared a counteroffensive that succeeded in badly maiming the infantry portion of the striking force and capturing a bunch of the artillery). The same striking force would have a hard time threatening Verdun without also diluting its capabilities for the real offensive.

Where an attack at Verdun could be useful would be if Germany could pinch off the salient, encircling and capturing the defenders, instead of pushing into the shoulders of the salient like in the 1915 battle. This more or less mirrors the OTL American battle plan against the St. Mihiel salient later in 1918. A successful encirclement (or a hasty withdrawal to escape the closing pincers) could inflict a massively favorable casualty ratio (as at St. Mihiel, where the American and French forces took 15k prisoners, captured 450 artillery pieces, and inflicting 7500 KIA/WIA in exchange for taking about 7k casualties themselves). Threatening such an encirclement could be an effective diversion, if the German Army could sell it as a serious threat without too badly diluting resources from the real offensive.

Aight, do you see the attack succeding better id it came from the west or east or even south?The big disadvantage of Verdun as an objective is that there's nothing strategically vital in or behind it. Verdun isn't a transit hub, nor is it a big population or industrial center, not is any of the above immediately threatened if Verdun falls. The main direct strategic benefit to Germany of taking Verdun, apart from morale effects, is that doing so would shorten the front, but shortening the front works both ways, and in Spring 1918 Germany has more manpower on the Western Front than the Entente so shortening the front probably helps the Entente more than Germany by reducing Germany's relative advantage in available forces for offensives or defensive reserves. Moreover, shortening the front by reducing a salient would leave Germany in the position of having to haul supplies and reinforcements through the fought-over grounds, so if Germany wanted to shorten the front they could do more advantageously by abandoning the adjacent St. Mihiel salient instead.

Verdun's disadvantages as a real objective also weaken its value as a diversion. If the Entente commanders have to choose between holding Verdun and holding Amiens or Hazebrouke, they're choosing the vital logistics hubs every time: losing Verdun would be an embarrassment and a nasty blow to morale, but losing the latter would cut off big chunks of the front from the rail network (requiring a large-scale withdrawal and possibly abandoning a bunch of heavy artillery) and open up Paris or the Channel Ports to follow-up offensives.

The other big problem with a diversion is that Germany's ability to simultaneously mount a convincing diversion and prepare a serious offensive to take advantage of it was questionable. The Spring Offensives relied on a single body of units for each major offensive operation, particularly the heavy artillery and the elite "stormtrooper" infantry that would lead the assaults. This is a big part of why the Spring Offensives petered out OTL (the same striking force was used over and over again, taking casualties and building up fatigue each time), and why Second Marne in particular was so devastating (Foch correctly anticipated the next strike and prepared a counteroffensive that succeeded in badly maiming the infantry portion of the striking force and capturing a bunch of the artillery). The same striking force would have a hard time threatening Verdun without also diluting its capabilities for the real offensive.

Where an attack at Verdun could be useful would be if Germany could pinch off the salient, encircling and capturing the defenders, instead of pushing into the shoulders of the salient like in the 1915 battle. This more or less mirrors the OTL American battle plan against the St. Mihiel salient later in 1918. A successful encirclement (or a hasty withdrawal to escape the closing pincers) could inflict a massively favorable casualty ratio (as at St. Mihiel, where the American and French forces took 15k prisoners, captured 450 artillery pieces, and inflicting 7500 KIA/WIA in exchange for taking about 7k casualties themselves). Threatening such an encirclement could be an effective diversion, if the German Army could sell it as a serious threat without too badly diluting resources from the real offensive.

I think Amiens and Hazebrouck in the North were the best objectives. The problem was Ludendorff in planning the Spring Offensives wasn't specifically targeting the supply hubs: the first two offensives (Michael and Georgette) came close to capturing Amiens and Hazebrouck respectively, but Ludendorff's planning had centered on generating breakthroughs in strategically interesting sectors and then exploiting them opportunistically, following an operational approach that had worked well on the Russian front. The Western Front was a tougher nut to crack, and both the more built-up infrastructure and the much greater density of troops called for an approach that focused on breaking enemy logistics on the strategic scale rather than simply overrunning positions.Aight, do you see the attack succeding better id it came from the west or east or even south?

I meant the attack on Verdun if it were to happen, would it have better chances west east or from the st.mihel salient?I think Amiens and Hazebrouck in the North were the best objectives. The problem was Ludendorff in planning the Spring Offensives wasn't specifically targeting the supply hubs: the first two offensives (Michael and Georgette) came close to capturing Amiens and Hazebrouck respectively, but Ludendorff's planning had centered on generating breakthroughs in strategically interesting sectors and then exploiting them opportunistically, following an operational approach that had worked well on the Russian front. The Western Front was a tougher nut to crack, and both the more built-up infrastructure and the much greater density of troops called for an approach that focused on breaking enemy logistics on the strategic scale rather than simply overrunning positions.

I think east, perhaps in the Argonne, or an encircling attack on Rheims, ultimately rolling up the French line with a series of attacks, the goal being to crush the life out of the French army to force a collapse, so a compromise peace is possible.I meant the attack on Verdun if it were to happen, would it have better chances west east or from the st.mihel salient?

It will have to be a compromise peace with Germany keeping most it's gains in the east, France could be offered a status quo 1914 peace.). Britain could keep some of it's colonial gains and be given a naval agreement.

There were two supply routes into Verdun: a broad-gauge rail line through St. Menehould in the North/East and a road (dubbed "the Sacred Way" for its essential role in supplying the French defenders in 1916) with a parallel narrow-gauge line built to supplement it in 1916. There's another broad-gauge line through St. Mihiel, but that's already cut by the German salient there. The St. Menehould line was close enough the the front that it could be cut by German artillery, as indeed it was in 1916. Once that's done, interrupting the Sacred Way would cut off Verdun from supply and reinforcement and probably force a precipitous withdrawal, so it makes sense to focus the main effort in that direction.I meant the attack on Verdun if it were to happen, would it have better chances west east or from the st.mihel salient?

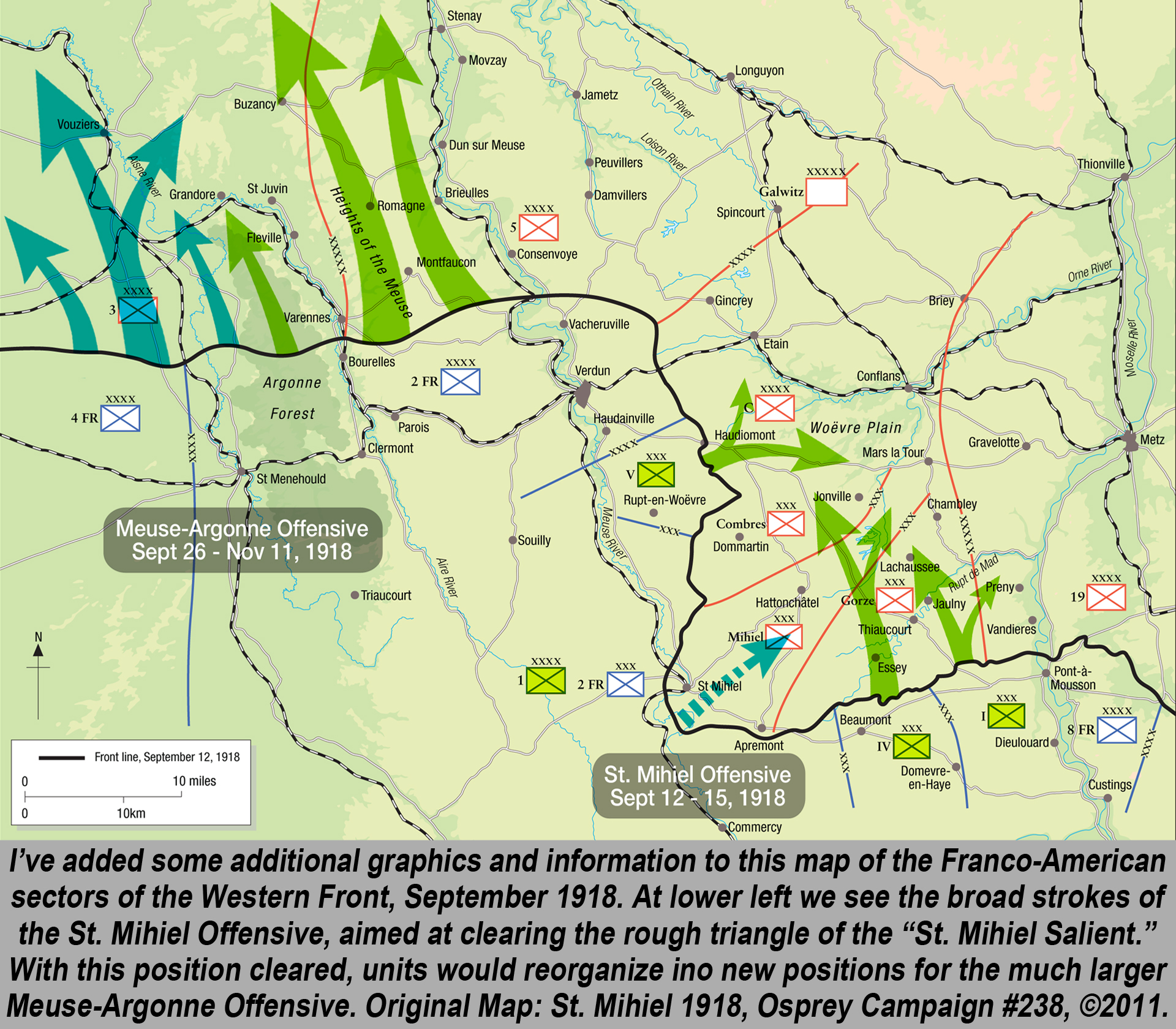

Looking at the below map (source) of the Verdun area in 1918, coming out of the St. Mihiel salient has a significantly shorter route to cut the road, but there are a couple difficulties. One is the Meuse river: the Germans have only a small bridgehead over it at the town of St. Mihiel itself and another to the south of it. The French would have known (being able to read a map as well at least as well as I can) that these are the obvious starting points to advance from in that part of the front, so the Germans would have to either obligingly push directly into the teeth of French defenses or they'd need to force contested crossings of the Meuse elsewhere as part of the opening phase of the push. The other big problem is that the German army would be coming out of the point of a salient, limiting the ability to stage infantry reserves and supplies for the offensive and to position artillery to support it.

Pushing through the Argonne instead, or on a slightly broader front straddling one or both rivers to either side of the Argonne, would give the Germans a much cleaner route of advance with a better jumping-off point. And the rivers look like they'd limit the ability of the French defenders to maneuver on interior lines once the Germans are passed St. Menehould and Clermont. And while the north-south roads and rail line parallel to the Aisne River are probably completely shredded around the front, there's an outside possibility that German engineers might patch up a connection that could allow trucks and wagons to bring up at least some supplies for the later phases of the offensive.

The first OTL spring offensive, Operation Michael, penetrated about 40 miles at its deepest point: a similar advance here would handily cut the Sacred Way and come close to linking up with the St. Mihiel salient. So I'd put the main effort in the North/East, probably positioning some infantry reserves and a few heavy artillery batteries in the St. Mihiel salient in order to launch a secondary offensive if the defenders weakened the front in that area in order to try to contain the breakthrough, and so the artillery could support the later phases of the offensive from the opposite side.

I'm not sure about "crush[ing] the life out of the French army" as an operational objective in 1918. With American mobilization quickly ramping up, attritional strategies are no longer viable paths to German victory. And the Entente powers know that American reinforcements are on the way, in enough numbers to more than make up their losses if they can hold out a few more months. In order to force a compromise peace, IMO Germany would need to take or seriously threaten a major strategic objective like Paris or the Channel Ports. A major victory at Verdun in 1918 could contribute to that, though, if France loses enough men, materiel, and morale to make a second offensive similar to Operation Michael more successful than OTL.I think east, perhaps in the Argonne, or an encircling attack on Rheims, ultimately rolling up the French line with a series of attacks, the goal being to crush the life out of the French army to force a collapse, so a compromise peace is possible.

It will have to be a compromise peace with Germany keeping most it's gains in the east, France could be offered a status quo 1914 peace.). Britain could keep some of it's colonial gains and be given a naval agreement.

I absolutely agree that a compromise peace would be necessary as an outright victory isn't really possible in 1918: even if France were somehow completely overrun, there's a bunch of salt water inconveniently full of battleships between Germany on one hand and the US and Britain on the other, and even with Ukrainian grain tributes the blockade is biting pretty hard on the German food supply. And in broad strokes I think you're right about what the peace would look like, although I'd also add complete evacuation from Belgium to your list. Austria and Bulgaria might also be required to evacuate most of Serbia, Albania, and Romania.

YesI'm not a great historian of the Western front. Are you talking about the offensives the Germans launched in Spring 1918?

Share: