Chapter I - The Rise and Fall of Erich Honecker: 1971 to 1984

Chapter I - The Rise and Fall of Erich Honecker: 1971 to 1984

The 8th party congress of the SED in 1971 proved to be a watershed event in the economic developent of the GDR, since it marked the end of the NÖSPL (,,Neues ökonomisches System der Planung und Leitung" - "New Economic System of Planning and Administrating"), the economic strategy adopted by the 6th party congress in 1963.

The underlying goals of NÖSPL had been to grant the individual enterprises more autonomy and to establish an efficient system of economic incentives. And in fact, during the first years of it's existence, the program had yielded very promising results. Between 1963 and 1970, the GDR's Gross Nation Product (GNP) grew by an annual average of 6%. At the 7th party congress in 1967, this system was further developed into the ÖSS (,,Ökonomisches System des Sozialismus" - "Economic System of Socialism"). Individual enterprises were given even more autonomy, the number of planning targets was drastically reduced and huge efforts were taken in order to overtake the west in the field of high technology (or in Ulbricht's words: ,,Überholen ohne Aufzuholen" - "Overtaking without Catching Up"). From the mid 1960s onwards, wages and pensions increased drastically. However in 1970, it became clear that the program was also responsible for serious economic difficulties. Skyrocketing investment in some key sectors (namely those of high technology) had caused investment rates in other sectors to drop, and in the end many enterprises failed to meet their planning targets. Shortages resulted and, combined with increased purchasing power, increasingly created a dangerous monetary overhang. Dissatisfaction spread amongst the populace and the efficiency of the ÖSS, every since a controversial topic in the party, began to be seriously questioned. Ulbricht remained stubborn though, and insisted on the continuation of the program. His friendly policy towards the FRG also caused a lot of dissent in the party. On 29th of March 1971, a group of dissatisfied Politburo members sent a secret letter to Leonid Brezhnev, basically asking for permission to replace Ulbricht. Brezhnev supported this proposal, and on May 3rd 1971, Ulbricht was forced to officially announce his resignation from the post of General Secretary of the SED (allthough he would remain Chairman of the Council of State untill his death two years later), ostensibly due to "old age". The Central Commitee elected Erich Honecker as his successor.

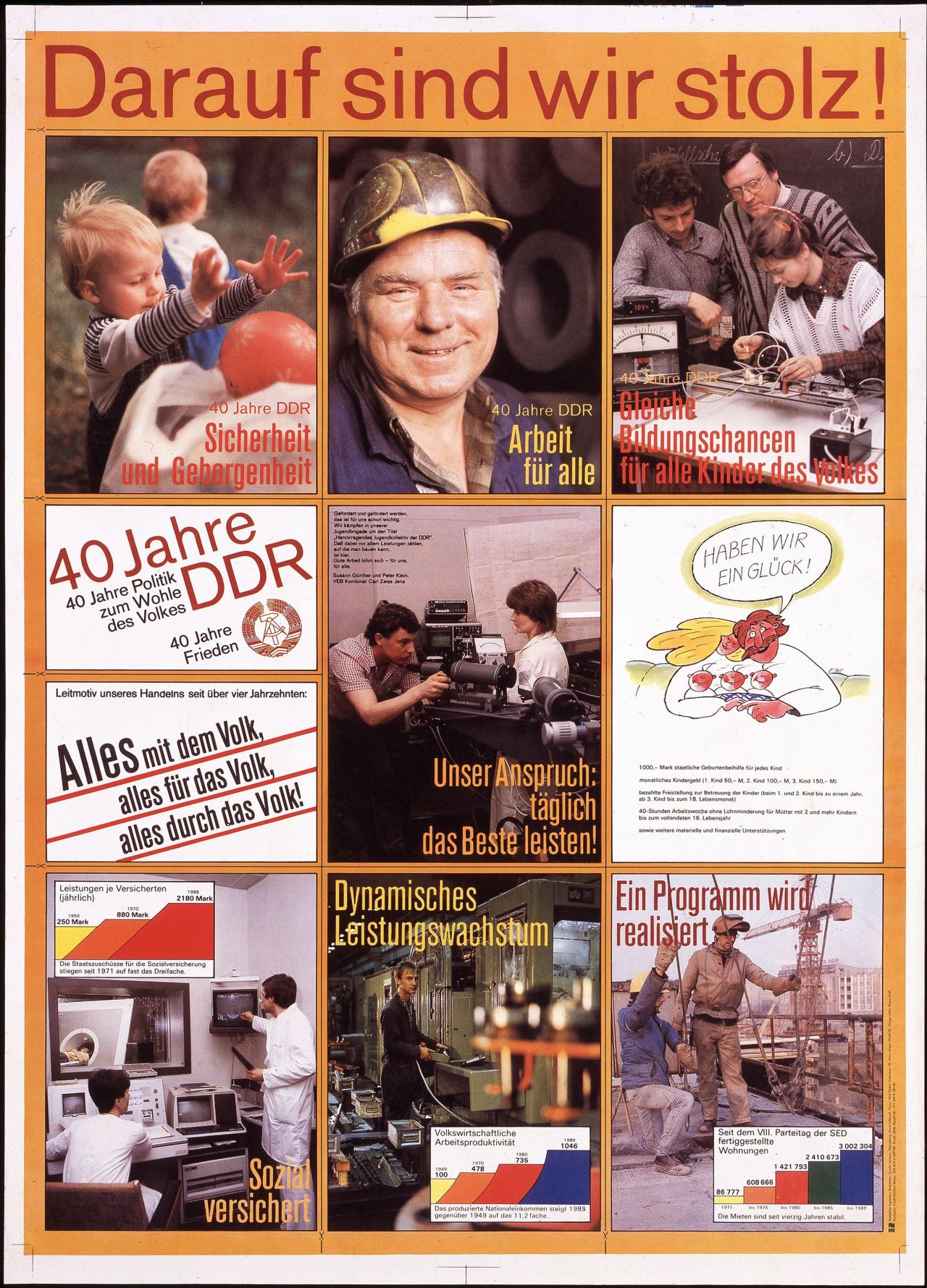

In this situation, between the 15th and 19th of June 1971, the 8th party congress of the SED took place. It was widely expected that this congress would mark a sharp turn in the field of economic policy, and these expectations proved to be right. The congress officially decided upon a new economic strategy, namely that of ,,Einheit von Wirtschafts- und Sozialpolitik" ("Unity of Economic and Social Policy"). This strategy was a direct result of the problems that came up as a result of the ÖSS, it's main goal beeing for economic growth to parallel the actual rise of living standarts. In order to guarantee the economic growth neccessary to fund the planned social programs, the change from primarily extensive to intensive reproduction was tackled from the early 1970s onwards. At the same time, individual enterprises were allowed to keep direct control over more of their profits in order to make an efficient and decentralized rationalization of production processes possible.

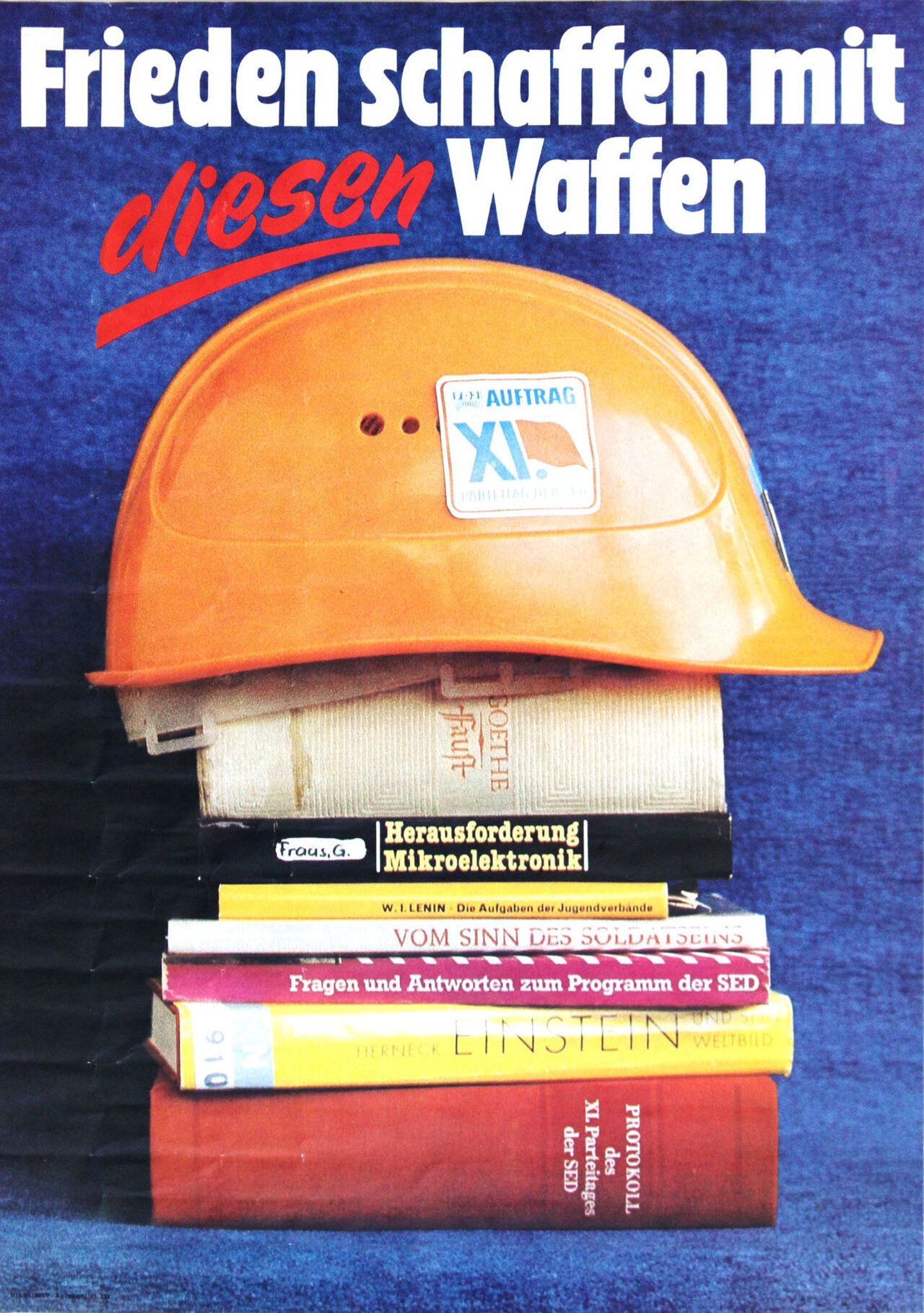

Overall, it was expected that this strategy would strenghen the party's popular support, while also increasing labour morale and therefore productivity. As part of this strategy a number of programs were launched, the most ambitious of these perhaps beeing the housing program. In 1971, the party promised that three million news flat were to be built untill 1990 in order to finally solve the GDR's chronic housing shortage - a result from the devastation caused by WW2 and the mass immigration of people from Silesia, Pomerania and East Prussia during the mid to late 1940s. Apart from that, subsidies on basic products were massively increased, to a point at which West Germans would travel to the GDR just to buy books en masse, which would be three to four times more expensive in the FRG. The "Unity of Economic and Social Policy" was largely successfull in increasing popular support during the 1970s, however labour moral actually decreased due to allmost total job security, aswell as lax controls and insufficient economic incentives. As a result productivity declined. However, this was not the only negative side effect of the strategy. The high costs of simultaneous economic inputs and far-reaching social programs increasingly had to be covered by foreign credits (imports of spare parts from the west proved to be especially costly). In the end, the "Unity of Economic and Social Policy" proved to be a failure as economic growth proved to be utterly insufficient to provide for these high expenditures. Foreign debt skyrocketed as a result. The underlying causes lay, for the most part, outside of the GDR's cotrol. The primary reason for the failure was the lack of a common economic strategy of the COMECON countries. Lofty dreams of socialist economic integration had long given way to a disempowerment of COMECON organs, which hurt the economic developent of all socialist nations. Another reason was the reduction of Soviet oil imports from the early 1980s onwards, begun under Brezhnev and continued under Andropov, Chernenko and eventually Gorbachev himself. Energy shortages caused interuptions in the production process and dealt serious damage to the allready stricken productivity. Last but not least, there was the escalating arms race from the late 1970s onwards, which forced the GDR to divert valuable ressources from the civilian to the military sector. All these factors combined caused the strategy's key goals to fall by the wayside and lead to a point at which debt repayment was the single most important expenditure of hard currency.

During the early to mid 1980s, it had become obvious that a new strategy was needed. However the state and party leadership faced a dilema. There were basically three ways to go on: 1.) Continue the strategy of "Unity of Economic and Social Policy", become increasingly more indebted to the west and eventually suffer bancruptcy. This way was completely unacceptable for it would lead to the collapse of the GDR's economy. 2.) Reduce the amount of inputs in order to safe money. However this would cause economic growth rates to decline even further, the technological disparity to the west to increase further, and at some point the party would innevitably be unable to afford the expensive social policies. This way was completely unacceptable aswell, for it would also lead to the collapse of the GDR's economy. 3.) Cut back the social policies - increase rents, reduce subsidies, and curb imports of consumer goods. In one rude word: austerity. This last way was the only one that could, in the long run, lead to the recovery of the economic situation, however it would be immensly unpopular with the people - it would have to be admited that the promises the party made could not be kept.

From 1983 onwards, with the events in Poland serving as a catalyst, the "Unity of Economic and Social Policy" would be criticized increasingly openly in the Central Commitee. Honecker rebuked all of it, stating that the strategy was and still is the way forward, depite temporary setbacks. However this was obviously false, and the majority of the Central Commitee recognized this fact. In the Politburo itself, a split became increasingly more visible (of course not to outside observers, the conflict was for the most part resolved behind closed doors). Günter Mittag, Joachim Hermann, and Hermann Axen backed Honecker, while Willi Stoph, Horst Sindermann, Horst Dohlus and Harry Tisch rallied around Egon Krenz, the newly elected Central Committee Secretary for Questions of Security, State and Law. Krenz increasingly became the face of the Central Commitee tendency that realized where the wind was blowing. On April 13th 1984, Krenz faction openly opposed Honecker in the Politburo and after a quick vote the later was removed from the post of General Secretary. The vote was not unanimous, with 14 votes for the removal and 7 against. 7 members of the Politburo abstained. At an extraordinary meeting of the Central Commitee three days later, Honecker officially anounce his resignation due to "reasons of health". Egon Krenz was unanimously elected as the new General Secretary of the SED. Ironically, Erich Honecker eventually lost power for the same reason he gained it: A failed economic policy.

Last edited: