And, IIRC, the Danish and Scottish, too in the OTL New England/New York...I think @Torbald has mentioned that the French will colonize the Southeastern U.S. (as in my timeline), and I'd still bet that the British and Dutch would get involved in colonization and exploration.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Una diferente ‘Plus Ultra’ - the Avís-Trastámara Kings of All Spain and the Indies (Updated 11/7)

- Thread starter Torbald

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 48 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

38. Ventos Divinos 39. The Great Turkish War - Part I: El Reino de África 40. The Great Turkish War - Part II: The One-Eyed Sultan 41. The Great Turkish War - Part III: Blood in the White Sea 42. The Great Turkish War - Part IV: Rûm 43. The Great Turkish War - Part V: Otranto 44. The Middle Sea Transformed 45. Ilhas de OfirHuh I never knew he said it.I think @Torbald has mentioned that the French will colonize the Southeastern U.S. (as in my timeline), and I'd still bet that the British and Dutch would get involved in colonization and exploration.

All that happened around the 17th Century though, but I’m assuming this time the Spanish have a far great interest in the Americas this time.

I think the scale of the defeat for the Ottomans depends more on the Habsburgs, Venetians, or Persians than on Spain. Spain will most likely fully reestablish control over the central Meditteranean, possibly retake Cyprus or Rhodes, but if this should be the beginning of the end for Turkey then Austria, Venice, and Persia would have to seize the golden opportunity.

I think it depends on how the Spanish envision their security.I think the scale of the defeat for the Ottomans depends more on the Habsburgs, Venetians, or Persians than on Spain. Spain will most likely fully reestablish control over the central Meditteranean, possibly retake Cyprus or Rhodes, but if this should be the beginning of the end for Turkey then Austria, Venice, and Persia would have to seize the golden opportunity.

I totally agree that first and foremost they would seek control over the Central Mediterranean, from Tunis to Tripoli. Cyprus however, is a former Venetian colony. So, Juan Pelayo may provide help to the Venetians to reclaim their colony, but I doubt he would have more ambitions. The thing about Rhodes, is that it is a great location to intercept the most important maritime route of the Ottoman Empire: the Kostantiniyye-Alexandria route. However, Rhodes itself would be isolated if the closest spanish base is Messina or Taranto.

That brings to me to the next point. To exercise any sort of control over the Aegean and protect outposts such as Rhodes or venetian Crete, Spain needs Morea (Peloponnese). The Cyclades Islands are small and poor so they cannot support a major spanish base. Not to mention that they don't have a natural port such as Mahon or Valletta. Now the Morea peninsula can be easily defended as the isthmus connecting it to the mainland is only 6,3 km wide. During the medieval era it was protected by a wall. I guess in the gunpowder era, the isthmus can be covered by star forts. Behind the isthmus lies the impressive citadel of Acrocorinth. In such senario, Juan Pelayo may be tempted to add in his titles "Prince of Achaia". Morea is a region from where both colonists and stradioti mercenaries can be recruited. Lastly, from what we have seen from its venetian occupation of latter centuries, it can relatively productive in terms of olive oil, figs, raisins, raw silk and especially wine.

A similar case can be made about a Principality of Albania and a Principality/Despotate of Epirus, as both regions act as staging grounds for an invasion of southern Italy (and itch for anti-ottoman revolts) while they are easily defendable by the Albanian Alps and the Korab and Pindus mountain ranges. Their people are already known to the Spanish either as refugees to Italy or mercenaries.

Last edited:

Catherine of Aragon rises from the grave, haranguing anyone who isn't helping against the Turks... 😂I wonder what's going on in England at this moment.

Last edited:

Absolutely amazing update, your writing of this war, and all others has been fantastic! I'm very interested to see how this ends, and I'm assuming it will end in a major setback for the Ottomans, sort of like what the Battle of Marathon was to the Persians, a nasty defeat, but it won't mean the end of their empire....

Good luck with the house!I apologize for the delay (been busy trying to buy a house), the update is nearing 10,000 words and is shaping up to be the longest one yet

And please don't apologise, it's not an obligation. We're all extremely grateful that you use your free time to write this masterpiece.

Quite.And please don't apologise, it's not an obligation. We're all extremely grateful that you use your free time to write this masterpiece.

43. The Great Turkish War - Part V: Otranto

~ The Great Turkish War ~

Part V:

- Otranto -

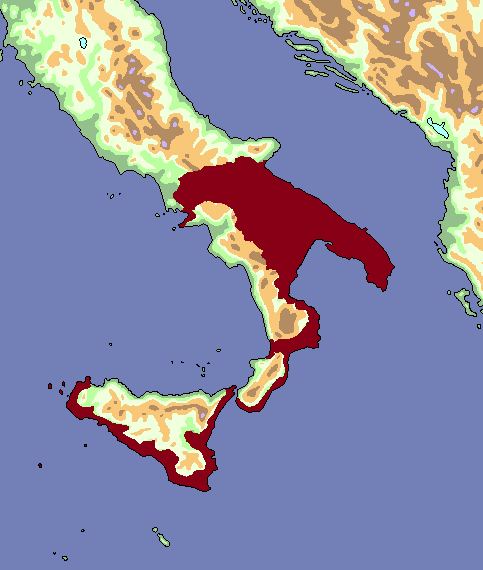

Italy under Ottoman occupation, c. 1573

Part V:

- Otranto -

Italy under Ottoman occupation, c. 1573

Having secured a victory at Nola as decisive and quick as the surprise capture of Otranto, Piyale Pasha had eliminated all meaningful resistance between him and the walls of Naples. However, the veteran Kapudan Pasha had great trouble in weighing the merits of descending into the Campanian Plain before Nola, and even now his mind was not fully decided on whether or not Naples should be put to siege. Piyale was a pragmatic man and knew that making a rush for Naples could either end in a historic conquest of a scale not seen since Mehmet the Conqueror, or in an abject failure that could set back Ottoman ambitions in the Mediterranean a whole century.

On one hand, Piyale had been presented with a golden opportunity: in just under 3 years, Ottoman forces had worked their way from the tip of Salento and the Adriatic to the Gulf of Salerno and the Tyrrhenian Sea. Turkish troops were closer now to Rome than they had ever been, and the response of Spain and the rest of Christendom was - as usual - too slow and too divided to slow their momentum. Every day spent discerning the feasibility of taking Naples was another moment that the Christian princes could spend, and which they had been spending on building up a counteroffensive to drive back the armies of Mehmet III. There were also reasons as to why the Ottoman campaign might fail if it did not seize Naples in a timely manner: if Piyale were to withdraw from Campania, an unsustainably lengthy military frontier would have to be established stretching across the hills of Molise, Apulia, and Calabria (compared to a more concise frontier from Molise to Naples), the likes of which would be spread too thin to properly hold back a concentrated Christian offensive and would likely put a massive yearly dent in the Ottoman treasury. With large numbers of Apulians and Calabrians regularly fleeing either into the unchecked countryside or into Christian-held territories, there would be very little taxable benefit in holding Southern Italy without the port of Naples, and more money would have to be spent in transplanting settlers from the Balkans and the Aegean to fill the empty towns and put the fields back to plow.

The success of the Italian campaign had also put Piyale under considerable pressure from the High Porte to seize the moment and undertake bolder actions. Mehmet III, who had spent so many of his younger years in the shadow of his elder, more zealous brother, Selim, had been shaped by the contest he had with his brother and longed to prove himself just as much a warrior of Allah. To Mehmet, there was no better way to prove this than by fomenting the eventual capture of Rome itself, allowing him to live up to both his sobriquet as the "Shadow of Allah upon the Earth" and the namesake of his predecessor, who had captured the second Rome - Constantinople - in 1453. This was indeed a very heady concoction of religious, patriotic, and quasi-apocalyptic symbolism that had been brewed in Mehmet's mind by these special circumstances, and it gradually drove him to feelings of overconfidence and to disregard many of the concerns of his military leadership. Mehmet greeted the news of Otranto and Nola ecstatically, and, according to the Venetian ambassador in Konstantiniyye, the sultan "had never carried himself with such joy and eagerness, [he] follows every word of the dispatches from Apulia with great excitement and relentlessly urges his Grand Admiral and his janissaries to push further and further still with every fortuitous gain."

On the other hand, the city of Naples was an imposing goal, even to the fearsome Ottoman war machine. Even after annihilating the Hispano-Neapolitan army and cutting down the viceroy, Iñigo López de Mendoza y Mendoza, at Nola, Piyale seriously reconsidered for a moment whether or not to pull back after sizing up the walls and artillery protecting Naples, acknowledging in private to his lieutenant Hüsnü that he may not have given the orders to take Naples had he not been filled with rage at the moment over the bloody sack of Tunis. The troops under Piyale's command may have broken through the imposing, cutting edge defenses of Otranto in less than two weeks, but Naples was no Otranto. With more than 100,000 inhabitants, Naples was one of the most populous cities in Europe and possibly the world - certainly the most populous in the Spanish Empire. It was more than the jewel of Spanish Italy, it was the nexus of the Christian Mediterranean, and had been armed, fortified, and shored up appropriately. When Occhiali disembarked near Salerno to meet with Piyale and give him an idea of the naval situation in the Tyrrhenian Sea, Occhiali, perhaps injudiciously, told Piyale to his face that he was a fool to expend what impetus his army and the campaign as a whole still had in biting off more than he could chew at Naples, rather than hunkering down and solidifying the gains made in Apulia and Calabria - which were already far greater than what was initially expected - and reestablishing the supply lines from the Maghreb by redirecting his forces to topple the stubborn Spanish resistance in Sicily and to retake Tunis.

After Juan Pelayo had overseen the capture of Tunis in 1572, however, Occhiali’s preferred plans were no more prudent than Piyale’s assault on Naples. One of Occhiali’s lieutenants, Sinan Reis, had been sent to resupply Müezzinzade Pasha and reconnoiter the Gulf of Tunis in late October of 1573. When Sinan returned, his assessment of Tunis was worse than anticipated: the city and its environs were crawling with Spanish and Italian soldiers, laborers, and engineers, and appeared to be almost completely devoid of the bulk of its native Muslim populace. With massive shipments of limestone slowly ferried overseas or extracted from the nearby hills, old fortifications were being repaired and new ones constructed - not only at Tunis and La Goletta, but at Radès, Kelibia, Hammamet, and Grombalia as well. According to a Maghrebi shepherd questioned by Sinan's men during a coastal incursion, the construction of Spanish fortifications were underway even at Mornaguia, some 20 kilometers inland from Tunis. The Hafsid sultan meanwhile had relocated what was left of his court to Kairouan, and showed no signs whatsoever of moving against the Spaniards in the near future.

With the recapture of Tunis off the table for the foreseeable future, the situation in Sicily became much more precarious. So long as that great port had been in Turkish hands, the Ottomans could essentially funnel the money, supplies, and soldiery of half the Maghreb directly into Sicily, and in less than a week's time if at short notice. In Spanish hands, the port of Tunis would ensure that Ottoman and Barbary forces in Western Sicily would be endlessly harassed by sea, and, more importantly, would provide a quick and easy supply line to Palermo, effectively allowing that city to hold out indefinitely in the event of a siege. Sicily was the beating heart of the Central Mediterranean, and if its harbors and grain supply were not decisively wrested from the Spanish before they deposited more of their tercios upon its shores, then the Ottoman position in Italy would remain exposed from both the North and the South, and would have to fight with its back against the wall for how long only God could tell.

Ultimately, the mounting fervor of the Ottoman military, brought on continuously by successive victories, swept aside all but the most serious concerns, and the naysayers and worried parties were outnumbered by those that saw the events of the past three years as an obvious sign from the heavens to carry on with confidence. Piyale was duty-bound - by his Sultan, his soldiers, and his faith - to press forward. There was also one factor that possibly tipped Piyale in favor of continuing the siege of Naples. As was to be expected, prior to 1570 the Spanish administration was not too keen on imparting any more military training or arms and armor on the notoriously insubordinate Italian populace than it absolutely needed to. This meant that when the bulk of the Spanish military was needed elsewhere (which was the case throughout most of the 1560s), Spanish Italy was usually left with garrison numbers unbefitting of its geopolitical importance. While the events of 1570 to 1573 may appear that the Spanish authorities in Italy were guilty of leaving the backdoor open, they cannot necessarily be blamed for underestimating the quickness with which the Ottomans blew through the coastline defenses in Apulia, nor for overestimating the willingness of much of the Italian populace to comply with Spanish orders and form a unified front of resistance. Between the fall of Otranto and the beginning of the siege of Naples, a common thread can be seen in which the Italians in the smaller towns often elected to abandon the Spanish garrisons - whether out of contempt for the Spaniards or (more likely) a realistic fear of Ottoman engineering and artillery - and fight the Turks on their own terms, usually in the form of guerrilla warfare. This was the primary (and perhaps solitary) source of comfort for Piyale Pasha - no matter how profuse the bastions, curtain walls, and cannonades of Spanish Italy, they were all simply undermanned.

For those who had been watching from a distance, the arrival of Piyale Pasha in Campania with 33,000 troops suddenly made the fearsome Ottomans appear much closer to the princes of Western and Central Europe than they were back in Apulia, and every inch the infernal Turk creeped closer to Rome re-imbued the rest of Christendom with a sense of seriousness and urgency. The full scale entrance of Ottoman-Barbary fleets in the Tyrrhenian Sea also brushed up against the heretofore (mostly) unaffected realms of France and Northern Italy in a way not seen since the days of Barbarossa, and heightened the demands for action. Before 1570 the corsair fleets sustained themselves with the profits and oarsmen from the plunder and slaves which came primarily from the south and east-facing coasts of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. With these regions in Turkish hands, funding and manning these galleys became more difficult, and the corsairs had to range further afield in order to keep Ottoman-Barbary naval supremacy in the Central Mediterranean solvent. From his base in Messina, Occhiali sent out smaller squadrons to raid as far as Liguria and Corsica - raiding Ostia, Follonica, Cecina, Biguglia and Levanto - while Piyale ordered similar expeditions along the Adriatic seaboard as far north as Rimini. This, of course, brought Ottoman ships well within the closest stomping grounds of the two maritime republics of Genoa and Venice - still two of the most formidable naval powers in the Mediterranean - as well as the territories of the Papal States and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany-Romagna. These expeditions lasted throughout much of 1573 and 1574, and with the princes of Christendom beginning to mount an initiative against the Turks and a Holy League finally declared, the affected states decided that now was the time to push back at sea. After separately failing to pin down a corsair fleet attempting to pillage Savona and another near Livorno, a Tuscan-Genoese fleet under the leadership of Giannettino Dorian assembled at the isle of Capraia to cut off whatever incoming corsairs were heading northward. Emerging from a winter storm near Pianosa in December of 1573, a Turkish fleet under Sinan Reis was surprised to encounter an amassed force of Italian galleys and was forced to give battle. After a few hours of confused combat, Sinan managed to withdraw his fleet in defeat, although the casualties and lost ships between the two fleets were roughly equal and Sinan was able to sack Porto Ercole on his way back to Messina.

Ottoman ships at Messina

For the Ottomans and especially the Barbary Corsairs, thinking they could continue to act with impunity in such a way whenever and wherever they pleased was only fanning the flames of the Holy League, and thus accelerating the mustering of its armies. Approving operations such as these was a shortsighted move on Mehmet III's part. While the necessity of raiding further north in order to ensure the subsistence of Ottoman-Barbary galleys was perhaps unavoidable, Mehmet had neglected his divide-and-conquer diplomacy and had stepped on the toes of too many potentially hostile parties, and was now earning the growing ire of virtually all of Western and Central Europe. What was more, these further-reaching raids indicated that the demands of Mehmet's Italian campaign had officially surpassed its allotted resources. Had a smaller scale campaign more directly concentrated on the Spanish been undertaken, these issues might not have arisen and a quick and easy conclusion with a victorious outcome may have been achieved. Nevertheless, a likely tremendous conquest and perhaps the very raison d'être of the Ottoman state were both on the line, and it was simply too late for Mehmet to back down.

Piyale meanwhile was receiving frequent criticism from the de facto commander of the Italian campaign's naval component, Occhiali. The old renegade was now in his 70s, and was growing increasingly impatient with the Kapudan Pasha and the Ottoman Sultan, to whom his allegiance was still rather circumstantial. Muslim naval superiority in the Central Mediterranean had not been significantly challenged since the battle of Vido in 1552, a fact that made Occhiali concerned that the Ottoman-Barbary fleets had gone untested for too long, and worried that Piyale and the rest of the Ottoman military apparatus had grown inattentive and overly confident in their ability to project naval power in Southern Italy. The results of the naval action at Tunis and Cagliari did not suggest an overall inferiority of Muslim naval capabilities, but were not very promising. The hostile defensive actions made by the Genoese and Tuscans accentuated these concerns, and made Occhiali wary of the outcome if and when Spanish and other Christian warships returned to the region in force, and targeted the Ottoman-Barbary fleet for a pitched battle.

- “... non praevalebunt adversus eam.” -

Immediately after the lightning re-capture of Cagliari and Tunis, the Spanish fleet had to remain docked for the rest of the year, cautiously guarding the gains made in the Central Mediterranean and engaging in short distance activity as large quantities of materiel for refitting and resupply were needed before further campaigning could undertaken. Apart from badly needed powder and shot - the vast majority of which had been spent on Turkish galleys and the ports of the Barbary Coast or had been deposited in Tunis and Cagliari - timber, canvas, pitch, and nails were also being slowly ferried from València for repairs, along with hundreds of tonnes of limestone to rebuild fortifications. A tense silence settled over the waters of the Central Mediterranean as each side hesitated to take up the offensive. The viceroy of Catalonia, Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga, had been hard at work since early 1572 amassing dozens of galleys at Cagliari and billeting 7 tercios in a vast system of barracks constructed across the Campidano lowlands. Requesens knew very well that Piyale was closely checking in on the Spanish center of operations in Cagliari - he saw the corsair patrols a few kilometers from the harbor on a regular basis. He made no attempt to intercept these scouting squadrons, however, as he knew that manipulating the information that made its way back to the Ottoman commander was much more auspicious than enshrouding himself in the fog of war. Requesens knew that Piyale's every action hinged on when and where a Spanish relief force was expected to arrive, and would sporadically scramble his galleys and then cruise them to Capoferrato or Sant’Antioco before returning to Cagliari to keep the Kapudan Pasha in a state of confusion, or at least on his toes. In constant apprehension over movement in Sardinia, Piyale proceeded to Naples with utmost caution. The city would only be fully on land encircled if a naval blockade could be established and maintained, and if this blockade was broken, or if there was a debilitating outbreak of disease or the casualties of battle became too much to bear, then a full disengagement would commence immediately. It was for these reasons that the route of withdrawal across the Southern Apennines to the Tavoliere delle Puglie was to be kept wide and extensively guarded.

Napoli

After vanquishing the 12 galleys and single galleass of Naples' garrison fleet, Occhiali decided that the Neapolitan harbor was too well-protected to approach closely, with numerous batteries mounted along its seawall and in the Castel dell'Ovo. By Piyale's reckoning, the entire Gulf of Naples - from Sorrento to Capri to Ischia to the Capo Miseno - would have to be bottled up, to which Occhiali objected that such a blockade would stretch his galleys thin, require constant patrols, and leave his ships exposed to sudden storms and other capricious weather. If the port of Sorrento could be taken, however, then it would be relatively easy to cut off all maritime movement in and out of Naples entirely. While half of Sorrento’s population had either fled the city or been killed or enslaved in previous raids, it remained a tough nut to crack. The port was guarded at sea by steep cliffs and on land by deep gorges, except for 300 meters on the south-west, where a protective wall stood. To the east, the bulk of Piyale’s army marched south to seize Castellammare di Stabia and close off the Sorrentine Peninsula, while Occhiali’s ships pounded the city and 900 janissaries and 1200 irregulars were disembarked near Marina di Puolo and instructed to scale the gorges to the north-west and take the town by surprise. This risky maneuver was a success, but only after nearly 200 valuable janissaries lost their lives scaling the cliffs, a matter which left Piyale infuriated with Occhiali’s insistence on taking Sorrento and widened the division between the two commanders.

The frustrating difficulty in taking Sorrento had become a recurring trend with the smaller projects of the Ottoman encirclement of Naples. These unanticipated complications came from the locals, as the resistance shown in Campania was markedly stiffer than that encountered in Apulia and Calabria, and numerous consecutive fortifications and strongpoints began to chip away at the Ottoman force as their defenders consistently refused surrender and often fought to the last man. After the initial resistance shown at Otranto, Brindisi, and Taranto, the Mezzogiorno was bowled over by the sheer awe of the Ottoman war machine, and dozens of towns surrendered left and right out of not only fear of the Turks but also apathy towards preserving Spanish rule. The gravity of the situation had now become fully realized by the native Southern Italians and desperation had truly begun to set in, and their resolve had hardened in the face of this final stand scenario in which they had unexpectedly found themselves in. A tentative expedition to Salerno was rebuffed at Nocera Inferiore - not even a town of great strategic importance - after the locals fought tooth and nail, losing the majority of their populace in the process. To the west, the 700 janissaries that emerged victorious in Sorrento had to hold down the town alone for 6 days as Piyale’s contingent was held up at Castellammare di Stabia for longer than expected when the defenders took to the Lattari Mountains. Across the gulf, the Castello Aragonese at Ischia and the Castello di Nisida both cost the Ottomans roughly 2,000 lives and 3 weeks to take. Even after these important fortresses and harbors were secure, control of the Gulf of Naples was still not complete, and the Lazian ports of Formia, Gaeta, Sperlonga, and Terracina continued to slip small, single-mast ships into the Gulf of Naples under the cover of night, trickling in supplies and reinforcements and extracting women and children refugees.

These small yet committed acts of bravery were a thorn in the side of Piyale Pasha, but still did very little to prevent or even slow the Ottoman advance to the walls of Naples, where they set up camp in April of 1573 (having wintered at Caserta after the battle of Nola). Over the preceding months, Piyale’s army was joined by an additional 12,000 troops and 10,000 slaves and other laborers and camp attendants drawn up from Calabria and Apulia. Aware of the impossibility of both retaking Tunis and holding down the gains made in Sicily with the forces available to Müezzinzade Ali and Damat Ibrahim, Piyale would have to make the siege of Naples proceed as quickly as was humanly possible. Luckily for Piyale, due to the more pressing threat of corsair violence over the previous decades, Naples was better fortified against a seaward approach than one by land. The west and south-facing walls were thick, well-planned, and dotted with triangular bastions, and consequently reducing the walls by artillery fire was out of the question, but the curtain wall was also too long to be sufficiently manned in every portion by Naples' 4,700 defenders. Piyale therefore planned to use his superior artillery and janissary sharpshooters to keep the Christian gunners hunkered down behind their parapet and thus protect his sappers, engineers, and slave laborers as they dug their tunnels. Optimally, 4 or 5 large and equally spaced tunnels could be dug in less than 2 weeks, and once the mines were planted and the fortifications above them blown open, there would be more breaches than the defenders could handle at once and the Turks could rely on sheer numbers to overwhelm them.

With the Spanish viceroy dead, the defense of Naples was now in the unlikely hands of Rudolf von Albeck, an Austrian Hospitaller from a lesser noble family in Carinthia, who was in Naples at the time alongside 300 of his brethren as head of a reinforcement effort to be sent to Malta but had been postponed indefinitely since 1570 given the circumstances at sea. In that time, Albeck had earned the trust and friendship of the Viceroy of Naples, Iñigo López de Mendoza y Mendoza, and was requested to lead the city’s war council because of this, as well as due to the not so insignificant fact that he was neither a subject of the king of Spain nor an Italian, and therefore was foreign to the Spanish-Italian power struggle in Naples and could be trusted to be impartial in political and cultural matters. Albeck quickly set about restoring Christian morale: Eucharistic processions around the Duomo and the surrounding streets began immediately after the arrival of the Ottoman army and continued every day, while the priests within the walls offered confessions and dispensed the Holy Sacrament for extended periods - often for as many as 40 hours at a time. Albeck was also influential in defusing the class and culture-based tensions dividing the military leadership in Naples, gathering the senior Hospitallers and the city's garrison commanders and their aides-de-camp together in the Castel Nuovo for a solemn ceremony in which all swore that whether Spaniard or Italian, noble or commoner, all would stand side by side as brothers through the tribulation before them, and all would lay down their lives for the Christian faith. Under Albeck’s supervision, the remaining 50,000 to 60,000 Neapolitans (more than 30,000 having fled the city since August of 1572) were restricted to strictly confined quarters of the city in order to allay the perpetual and potentially cataclysmic threat of disease. With only 4,700 professional soldiers under his command, Albeck had to defend the most important city in Spanish Italy against a force 10 times larger.

There was one glaring issue for Piyale. Overlooking the city of Naples from the north was the promontory of Vomero, atop which was perched the fortress of Castel Sant’Elmo. Piyale (always the pragmatist) knew that it was unlikely that his 45,000 man army would emerge from the siege of Naples with sufficient numbers or morale to take on an army sent by the Holy League on an open field. With news arriving that Italian, German, and French noblemen and their retinues were gradually assembling in the Roman suburbs along with companies of landsknechts, gendarmes, and condottieri, Piyale also knew that such an army would arrive soon after Naples was taken. With such an impending threat looming from the north, the Ottomans needed to secure the city’s chief northward fortification, ideally before an assault on the rest of the city was undertaken. No matter the numerical superiority of the Turks, storming a breached wall was always an extremely costly affair, and, with the bitter opposition shown by the Campanians thus far, Piyale estimated almost 10,000 of his own would perish unless Sant’Elmo was taken first, or at least neutralized in some way. After 8 days traipsing through the steaming, volcanic Campi Flegrei to the west, 9,000 soldiers, laborers, engineers, and artillerymen under the command of a Greek renegade known as Erhan Bey prepared themselves for the siege of Castel Sant’Elmo. After hearing of the Turkish approach, Albeck sent 120 of his Hospitaller brethren to reinforce Sant'Elmo and the Certosa, voluntarily captained by a Hospitaller of Converso origin, Melchior de Montserrat. Inspired by this Jewish convert putting himself on the frontlines, the morale of the vastly outnumbered garrison was bolstered. Castel Sant'Elmo was only large enough to hold 500 to 600 defenders at a time, with an additional 300 to 400 in the underlying monastery complex, the Certosa di San Martino - a paltry sum compared to the 9,000 assembling at the foot of Vomero. What was more, the primary purpose of the Castel Sant'Elmo was to overlook Naples and discourage rebellion, with the protection of Naples' under-defended northwest being secondary. The northwest approach to Sant'Elmo was uphill, but nowhere near as precipitous as any southeast means of retreat for its defenders. This meant that the 800 or so men on Vomero would be fighting with their back to the promontory, making an organized retreat virtually impossible. They would have to fight to the death.

However, that relatively small hilltop fort was more stout than any in Piyale’s camp had truly anticipated. Sant’Elmo had been rebuilt from 1537 to 1547 under the orders of Pedro de Toledo y Zúñiga, the alcalde of Naples under the viceroyalty of Fernando de Portugal, who had recruited a military architect from València named Pedro Luis Escriva to redesign it. The fort was renovated in an unconventional hexagonal star shape, which attracted intense criticism, leading Escriva to publish a written defense of his design. This hexagonal renovation ultimately proved to be prescient, and the Castel Sant'Elmo - long considered a symbol of Spanish oppression - would become a symbol of Neapolitan resilience. The uphill route to Sant'Elmo was smooth enough, but was void of any trees or large boulders for cover, and still left any approaching attackers painfully vulnerable. The uphill angle also made bombarding the fort extremely difficult, and, without any nearby vantage point to aim from, many of the rounds fired by the Ottomans either fell short or hit only the base of Sant'Elmo. The most difficult obstacle was the elevation of Sant'Elmo itself, which was constructed on top of a stone base several meters tall. The high walls, which had numerous embrasures, were guarded also by a double tenaille and a moat. Unless greater suppressing fire could be brought down on the fort, it remained a perfect sniper's den, and the bodies of unfortunate slaves and inattentive janissaries and sipahis continued to stack up in the ditches, riddled with arquebus holes. Erhan decided to encroach on the battlements by digging out lines of trenches and mounting protective earthworks progressively up the hill, a task to which hundreds of slave laborers - most of whom were Christian - were put to work. While at work, many of the slaves would often drop their shovel or pick and stand up, waving their arms and shouting to the gunners on Sant'Elmo that they were Christian, and to spare them. Regardless, most of the slaves that exposed themselves were shot on sight.

Piyale Pasha anticipated that Sant'Elmo would last only two weeks if a breach could be made, and, if not, only two weeks more with the supplies available to the defenders. These expectations were not a proper assessment of the difficulty awaiting the Ottoman troops, and were not met by Erhan Bey. The withering gunfire and ordnance frequently overwhelmed the Ottoman line if an unprotected advance was made, and they were most often forced to keep whatever distance they could. So voluminous and thick was the constant pillar of gunsmoke rising from Sant'Elmo that the onlookers in Naples compared it to a miniature Vesuvius. Whenever the Ottomans made a push attempting to stack ladders against the walls and climb them (usually at night), they were met not only by bullets but also by bounding, terrifying "fire hoops," an innovation provided by the Hospitaller knight Ramon Fortuyn. Using rings of iron originally intended as barrel hoops, the fire hoops were coated with caulking tow and then steeped in boiling tar, a process which was repeated until they were as thick as a man's leg. After being lifted over the parapet with a large pair of tongs, the fire hoops were lit and sent careening down the hillside. The psychological effect of these bouncing circles of hellfire was obviously profound, but the physical damage they inflicted was measurable as well, especially among the janissaries, whose loose robes made them particularly susceptible to catching fire. With no well, stream, or other body of water nearby to douse themselves, these unfortunate soldiers simply ran and screamed until they died in agony, often spreading the flames (and fear) to others if their accompanying squadron was more tightly packed. The rough terrain of the outlying Campi Flegrei also made resupply very difficult, and every week a day or two would pass in which the Ottoman artillery and sharpshooters would go completely silent for lack of powder and shot.

When the charges were finally set, the explosion blew a chunk out of Sant'Elmo's foundation, but left no damage to the upper walls. Unable to create a ramp into the fort by reducing the walls with artillery and tunnels, and under too much suppressing fire to attempt to scale the walls with ladders, Erhan opted to encircle Sant'Elmo instead and starve the defenders out. This change of plans required at least a week more of trench-digging to round Vomero and reach the walls of the Certosa di San Martino. The days passed as they had before, although von Albeck made sure to send additional munitions, polearms, axes, wooden planks, and a company of arquebusiers along the Petraio footpath (the only road connecting Naples to Vomero) to reinforce, rearm, and repair the rudimentary defences of San Martino after receiving news of Ottoman movement in that direction. After a painful 8 days digging and stacking rocks and dirt for bulwarks to absorb arquebus shots, the Ottoman line finally came within distance of the Certosa acceptable for a mass assault. After an intense 7 hours spent furiously exchanging gunfire and then fighting hand to hand in the hallways of the Certosa, Ottoman troops had secured the monastic grounds and cut off Sant'Elmo from Naples. As the Certosa also functioned as the sick bay for Sant'Elmo, it housed dozens of wounded defenders,, all of whom were shot or gutted in their beds. The fort remained unassailable, however, and the Ottomans had to remain hunkered down in San Martino or keep their heads ducked in the hillside trenches, unable to descend down the Petraio into Naples proper as well for fear of the gunners atop Sant'Elmo, merely a few hundred meters above them.

The Ottoman contingent at Vomero might have been more regularly supplied and supported had Piyale Pasha not simultaneously been preoccupied with preparing for a mass assault on the curtain wall of Naples. Aware of the infernal efficiency and precision with which the Ottoman engineering corps was known to operate, Albeck ordered frequent sorties to raid the Ottoman trenches and mines and inflict whatever damage they could. Counter-tunnels were also dug to take the Ottoman miners head on, or to run parallel with the Ottoman tunnels and then be detonated, collapsing both. Large casualties were usually taken and important officers sometimes captured in these sorties, and the dangers of digging tunnels also meant that many of the defenders lost their lives needlessly underground, but these operations succeeded in delaying Piyale's plans until late June. Once the carts full of dirt and stone stopped emerging from the Ottoman tunnels, the defenders knew the charges would soon be set and ignited at any moment, and girded themselves accordingly. At around 5 AM on June 23rd, two massive explosions collapsed sections of the curtain wall. While the reverberation of the falling wall faded, the air filled with the customary “Allahu akbar” that preceded a charge, which grew deafening as its roar was picked up by 22,000 attackers, countered from the walls by cries of “¡Santiago!” and “Gennaro!” Something was wrong, however. The Turks had spent weeks digging 4 tunnels, not 2. Furious over the delay, Piyale rode to the southwestern front, where Dervish Bey, governor of the sanjak of Shkodër, had been tasked with supervising the siegeworks. Blaming the slave and criminal laborers for laziness and intransigence, Dervish Bey informed Piyale that one tunnel had been deluged in an unseasonal rain storm 4 days before, and the sappers had not yet finished digging out all the runoff mud, while the charges in the other tunnel simply fizzled out, and had to be reset. The latter tunnel was detonated that same day and the former a week later, but Piyale’s intended strategy of surprising and overwhelming the defenders at four separate points simultaneously - and thus ensuring a quick and relatively painless victory - was foiled. After two hours had passed and the other two breaches failed to materialize, Von Albeck deduced that they Turks had either encountered difficulties or had dug the southwestern tunnels to confuse the defenders and spread them as thinly along the wall as was possible, and promptly ordered the bulk of his forces to relocate to the northwest. Thousands of Ottoman troops remained in their trenches in the southwest, while the rest of the assault took on the full brunt of the defenders to the north. The first assault failed, although the attackers gave as good as they got. Assaults on these breaches would continue regularly, both at night and during the day, every two to three days for the next 4 weeks. While morale was dwindling in Naples, it was likewise sagging in the Ottoman camp. Piyale’s troops had been on campaign almost nonstop for the past three years, and the wear and tear was now being profoundly exacerbated by the defiance encountered in Campania. Embittered by the death of their brothers in arms and impatient with the prolonged siege, the Turkish army flouted Piyale’s original policy of leniency towards the native population in increasingly savage ways on a daily basis, which only served to strengthen the resolve of those within the walls of Naples, who violently returned the Turks’ hatred whenever and wherever they could. Mutinous discontent simmered within the Ottoman ranks.

Rudolf von Albeck (center) leads the defense of Naples

Things continued to develop in an unpredictable manner for Piyale. More intent on demoralizing and distracting the defenders, Piyale aimed his cannons not at the walls but over them, hoping to terrorize the inhabitants and possibly start a fire or hit a gunpowder magazine. The Neapolitans responded by removing cobblestone from the streets and dumping buckets of seawater on the exposed dirt, creating mud patches into which the Ottoman shells sunk harmlessly. Some explosive rounds landed in just the right spot, however. Once the drier summer months came around, the risk of fires started by Ottoman ordnance increased, with sporadic, small-scale fires throughout July and August caused by explosive shells. On one particular July afternoon, a flaming, bitumen-wrapped cannonball crashed into the slums in the northeast corner of the city unnoticed and began to spread. With an Ottoman assault underway at the southernmost breach in the walls, there weren't enough men available to stamp out the fire early on, and it soon became an inferno once it reached a minor gunpowder depot, the explosion of which threw the embers to the wind, spreading it further. Watching a quarter of Naples become enveloped in black smoke, Piyale Pasha seized on this opportunity and ordered his lieutenants to direct a general assault on every breach. Von Albeck had every bell in the city rung and sent detachments door to door to bring out every able-bodied man. Roughly 10,000 in all were called up, much of whom were boys and elderly men, and were handed either buckets of water and wet blankets or whatever weapon could be found for them - hammers, cudgels, rocks, butcher's knives, woodcutting axes, and even sharpened broomstick. All those who were chosen to fight were sent to the breach palisades, where the professional Spanish troops and the veterans of the Italian garrison formed the front ranks along with the more experienced Knights of St. John. Ottoman troops at the two northernmost breaches were able to force their way inside the walls three times, and on numerous occasions it seemed certain that the collapse of Naples' defenses was imminent. Nevertheless, with a raging firestorm at their backs and the Ottoman Empire's toughest troops slinging bullets and arrows and swinging scimitars at their faces, Naples' defenders held the line, and after 6 hours of combat, Piyale ordered a retreat from the walls. With the defenses of Naples at their weakest, Piyale would nonetheless be unable to quickly organize another large assault, as a potential catalyst for the Holy League’s long-awaited march southwards had just arrived in Rome.

Charles X of France was initially keen on providing whatever military assistance he could to drive back the Turks, but his enthusiasm was deflated by opposition from Kaiser Philipp II, who was prudent to a fault, and - as was to be expected - was not in the least bit enthused by the idea of French armies marching across Northern Italy once more, no matter their intent or destination. At first merely reluctant to allow French troops passage within the Empire, Philipp's concerns were doubled when the young Duke of Lorraine, Charles III, (his imperial vassal) insisted on marching alongside the French expedition to Italy. Imperial troops were sent to man the Alpine Passes into Savoy as well as forts along the Rhine and the cities of Basel and Geneva. Outraged at this overly defensive response to his request to join his forces to the Holy League (which Philipp II was instrumental in creating) - especially at a time when the defense of Christendom was at stake - Charles X retracted his promises and refused to talk anymore about involvement in Italy. The crusading spirit of the eldest daughter of the Church was not stillborn, however. Jealousy had been brewing among the peerage of France over the house of Guise’s newfound proximity to the king after the Sainte-Ligue descended on Paris in 1560, and by 1572 the duke of Guise, François, and his son Henri had more or less become personae non gratae at the French court, largely due to the machinations of the diplomat Michel de l'Hôpital and François de Montmorency, the marshal of France. Unable (at least temporarily) to provide military assistance at home against the rebellious Farelard Confederates and wary of nefarious plots in Paris, François relocated to Château du Grand Jardin, his family estate in Joinville. Looking to distance his son from any hostile actions by royal courtiers, François gave Henri permission to undertake an ambitious plan to fulfill their Christian duty, bring prestige to France, and hopefully restore the House of Guise’s good name at home by assembling an army in Italy - independent of royal assistance or even consent - to protect Rome against the Turks.

Taking the roundabout route from the family estates in Champagne with 600 retainers and gendarmes, Henri de Guise gathered another 1,200 through Picardy and along the Loire, and 700 in Aquitaine gifted by the League of Rodez, a chapter of the Holy League. Blocked from descending in Piemonte, Henri welcomed another 2,000 Provençal volunteers on his way to Marseille, along with 1,500 more from Savoy and Liguria. Luckily the House of Guise had friendly relations with the Dorias of Genoa, and were able to bypass the Imperial garrisons in the Alps by embarking on a fleet of Genoese galleys, which unloaded them at Fiumicino in Lazio in May of 1573. After his arrival in Rome, Henri’s expedition was joined by an assembled group of French expatriates and the condottieri and Swiss mercenaries whose services they had purchased upon hearing of his embarkation in Provence - numbering 2,500. Henri was invited to join the commanders appointed to defend Rome: Alfonso II d'Este, the Duke of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio, Francesco Ferdinando d’Ávalos d'Aquino, the marquis of Pescara and Vasto, Francesco Maria II della Rovere, the son of the Duke of Urbino, and Karl von Habsburg, the cousin of Kaiser Philipp II and Landkomtur of the bailiwick of Austria. The number of armed men committed to the Holy League now tallied at roughly 18,000.

Anxious over the army mustering at Rome, Mehmet III did what he could to attempt to jolt the Habsburgs back eastwards by sending an 8,000 man army (mostly Slavic yayas) to Belgrade, and 3,000 Tatar horsemen to raid Transylvania. Temesköz and the region around Déva were badly pillaged, but Philipp II called the Sultan’s bluff and continued to oversee the mustering of troops for the Holy League in Lombardy. With the winter rains approaching and the campaigning season drawing to a close, Piyale Pasha needed to act quickly and dramatically in order to either galvanize a peace offering from the Holy League or demoralize Naples into surrender. With Naples still holding out - albeit feebly - and Christian forces arriving piecemeal in Lazio, Piyale decided that only the boldest show of force would topple the still-flimsy Christian relief and shock the Holy League into a favorable ceasefire - or at least prevent a full scale withdrawal from Campania. Unexpectedly, Piyale detached a contingent of his best artillery crews and a supplemental force of 3,000 janissaries, placing them under the command of Hüsnü Bey and sending them north to march double-time over the tumultuous hill country and surround Benevento. Although well-fortified (if undermanned), this outlier fell in just two weeks and was left with a minimal garrison before the bulk of this contingent left to link up with another 12,000 separated from the siege at Naples, marching directly towards Rome. Piyale’s orders to Hüsnü were specific and cautious: get as close to Rome as possible and rain terror on the Roman suburbs, draw out a contingent of the coalition's forces into a disadvantageous position, inflict as much damage as possible, and pull back to Campania if Turkish losses were mounting too quickly or too disproportionately. Fortunately for the Holy League, an unnamed Benedictine monk - having witnessed the rapid arrival of the Turks along the Valle Latina from nearby Monte Cassino - made the bold decision to descend from the monastery just barely ahead of the Turkish army and ride as hard as he could to Rome to alert Henri de Guise. Piyale’s gambit produced part of its desired effect among the officers of the Holy League in Rome, who greeted the news with some panic, unsure if this meant Naples had fallen and that now the Turks were prepared to throw their full weight at the Eternal City.

The charismatic Henri de Guise was instrumental in rallying the members of the Holy League to act as quickly as possible, in order to ensure any armed confrontation took place far from Rome. The disparate components of the Holy League were slow to coalesce into a unified fighting force, and were unable to take up a favorable position at Frosinone, nor to prevent its sack by the Turks, but were able to stop Hüsnü Bey in his tracks at Palestrina - only 30 kilometers from Rome. From its vantage point on a hilltop near San Bartolomeo, the Ottoman artillery was able to cut the Holy League’s line to ribbons, and the northeast flank under Alfonso II d'Este buckled when Hüsnü ordered a company of janissaries to seize on the wavering Italian troops, breaking up their ranks with a barrage of grandes followed by a charge. Henri de Guise’s line held, however - even to the detriment of the young French nobleman, who took an arquebus ball to the cheek but continued fighting - preventing the Ottomans from collapsing the army of the Holy League entirely. The retreating Christian lines also drew more Ottoman troops within range of their enemy’s artillery, further disintegrating the cohesion of either army, devolving the battle into chaos. As the day was humid and windless, the field had quickly filled with a heavy cloud of gunsmoke, spoiling the momentum of the Turkish charge and obscuring the line of sight for the arquebusiers and artilleryman of both sides, leading to misplaced shots that ended in devastating friendly fire. As the battle spiraled out of control, the Ottoman artillery suddenly came under direct threat by Karl von Habsburg, who had intended to outmaneuver a company of flanking sipahis and ended up on the edge of the Ottoman camp. With landsknechts spilling in dangerously close to his own tent, Hüsnü drew back his janissaries to protect the Ottoman baggage, and then sounded a retreat. After the smoke cleared, around 3,000 Ottoman troops had been killed or captured, and 16 Ottoman cannons were seized. In comparison, the losses suffered by the Holy League were severe, with more than 6,000 dead or wounded. Still, the fact that the intruding Turks had successfully been driven off offered a major morale boost to the members of the Holy League, who felt this to be a sign that the tide was beginning to turn in their favor. The Christian leaders were surprised to discover, however, that this was not the army of Piyale Pasha and that Naples was in fact still in Spanish hands, and were disturbed to learn that this army that had nearly bowled over the combined forces of the Holy League was merely a probing contingent (albeit one with a large component of elite janissaries).

The encounter at Palestrina had not ended up fulfilling its intended purpose for the Ottomans at Naples, who had meanwhile failed to fully penetrate the walls of Naples, and had not succeeded in starving out Castel Sant’Elmo, the assault on which alone had cost the Ottomans no less than 3,500 lives. The long awaited and perhaps inevitable outbreak of disease struck in early October as dysentery diffused through the Ottoman camp, exacerbated by the onset of torrential Autumn rain. Risking a jeopardized withdrawal due to the muddying roads and wary of news of the Spanish in Cagliari preparing to relieve the city, Piyale accepted that 1573 would not be the year in which Naples was to be taken, and somberly gave the orders to strike camp and begin the laborious journey eastwards. Over the 6 and a half months of siege, no less than 20,000 Neapolitans and Campanians had lost their lives. With all things considered, the Kapudan Pasha had performed well given his circumstances, and was able to make an orderly withdrawal with most of his army back to Cerignola, leaving behind a heavily battered Naples. Deep-seated indignation towards Naples and anxiety about the displeasure of his Sultan were both welling up within Piyale, who immediately set about making plans to return to Naples at the beginning of Spring, this time with a vengeance.

- Milites Christi -

Swiss mercenaries and landsknechts on Habsburg payroll (as well as Austrian and Tyrolean levies) had been crucial to the victory at Palestrina, meaning that any further action depended on the sustained agreement between the Holy League’s Spanish and Habsburg parties. Naturally, the Holy League entered a deadlock as Philipp II became more conditional with the usage of his soldiers, and the victory at Palestrina would therefore not be quickly followed up. After Palestrina, nearly three months were spent in negotiation among representatives of the Holy League, primarily between the Habsburgs, represented by Philipp II's Flemish ambassador, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, and the Spanish, represented by Juan Pelayo’s cousin, Emanuele, duke of Calabria, who met regularly in the Apostolic Palace on Vatican Hill and were mediated by Pope Pius V. Emanuele reminded his audience that Naples was, of course, still under siege, and as long as it was in great peril, Rome would be as well. He asserted that if Naples - being the most important city in Southern Italy and, more importantly, a mere 200 kilometers away - were to fall, the Turks would have in Naples the perfect operating base and would surely waste no time in returning to Rome - although next time not with 15,000 troops, but 150,000. Busbecq informed Emanuele that his Kaiser still wished to do all in his power to quicken the demise of the Turks, and that he deeply cherished the long standing friendship between the Houses of Austria and Spain, but he also needed to be sensible with the resources available to him - after all, had the 20 Years’ War not proven that the Habsburgs’ fight against heresy in the heart of Christendom was no less important than the Avis-Trastámaras’ struggle against Islam? It was common knowledge that after decades of constant warfare the House of Habsburg was struggling to either pay off or postpone payments on their staggering debt, and, with social upheaval in the Netherlands, growing tensions with Denmark, and the Hungarian frontier still vulnerable to the Turks, Philipp II insisted that any further assistance to Spain be withheld unless significant concessions and guarantees could be secured from Juan Pelayo. Busbecq laid out his liege’s terms accordingly, in three straightforward requests:

- The remission of 4 million ducats in outstanding debt owed to the Casa de Prestación and its affiliate enterprises

- A new 2 million ducat loan from the Casa de Prestación at no more than 6% interest

- the opening of the heretofore off-limits ports of Spanish America to trade with the cities of Antwerp and Dordrecht.

Money was easy enough for the king of Spain to part with (or so he thought), but the opening of his American empire to foreigners was nearly intolerable. Having overcome an extremely difficult rebellion in Nueva Vizcaya from 1552 to 1558 that threatened to kill the Spanish treasury’s most prized cash cow, Juan Pelayo was extremely cautious when it came to loosening Spanish America’s reliance on Spain proper, but with Piyale Pasha amassing troops just across the Apennines and Naples’ defences in critical condition, this momentous concession had to be made. Similar guarantees had to be made to persuade the other powerful assets of the Holy League into taking further action. Piyale Pasha had meanwhile supplemented his decimated army with every nonessential garrison and patrol in Apulia and Calabria, and convinced Mehmet III to empty the garrisons of much of Bosnia, Serbia, Albania, and all of Greece except for the Peloponnese and Chalcis, and to have them ferried to Italy posthaste. When Piyale Pasha re-entered Campania in May of 1574, his ground quaking army numbered a terrifying 77,000. The Spanish and the other members of the Holy League were now racing fervently to reinforce Naples before Piyale’s impossibly large army overwhelmed it. Having been preparing a proper army to contest the Ottomans in Italy for the last year and a half, Spain’s troop ships swept into the Gulf of Gaeta not a moment too soon. Unloaded to the north of Naples from Sardinia were 7 tercios numbering 21,000, along with 3,500 light cavalry and 2,500 artillerymen and engineers, all under the leadership of none other Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba. Those in the Holy League’s camp at Aversa cheered at the arrival of so many Spaniards, and the Italian princes conferred leadership to the Iron Duke. Giving the north and south flanks to Karl von Habsburg and Emanuele of Calabria, the Duke of Alba commanded 27,000 Spaniards, 7,000 Neapolitans, and 11,000 condottieri, landsknechts, and other mercenaries and troops in the employ of the Habsburgs and a number of Italian princes. Not wanting the Ottomans to encircle him and put his back to the sea, the Duke of Alba decided to take Piyale Pasha head-on at the outskirts of Naples near the city of Caserta.

The battle of Caserta was by far the largest land battle of what came to be known as the Great Turkish War, and would prove to be something of a definitive face-off between the strengths of the Ottoman and Spanish Empires. The janissaries lived up to their legacy as the fearsome shock troops of the Ottoman Sultan. Unlike their Christian adversaries, the janissaries had known literally nothing but warfare since their adolescence, and were proficient not only with their scimitars and arquebuses, but with polarms, bows, daggers, and grenades of glass and porcelain. Under the right circumstances, they could bust up a tercio formation with either a hail of their grenades or with the superior range of their arquebuses. There were, however, only 9,000 janissaries at Caserta, and only 14,000 in the world. The rest of the Ottoman infantry left much to be desired when weighed against a Spanish tercio or a seasoned company of landsknechts or condottieri. It was this dead weight that the janissaries essentially had to carry and cover for, and it was simply impossible for them to be sent every single place on the battlefield where they needed to be and when. On the other side, a company of a Spanish tercio could only be broken up if it was properly isolated or under pressure from some drastic disturbance, such as a well-placed artillery volley. At even numbers, the piqueros, rodeleros, and arcabuceros of a veteran tercio were perhaps evenly matched (at best) with the janissaries, but when two companies converged on a company of janissaries in pincer-like formation - even at inferior numbers - the janissaries were usually overwhelmed. The battle of Caserta would therefore prove whether the individual strength and expertise of elite soldiers like the janissaries and sipahis could overcome the advancements made in mixed unit tactics in Western and Central Europe.

While the Ottoman army was as formidable as many feared, the only other significant advantage they had over most European armies they encountered was their superior firearms and artillery. However, while the Ottoman marksmen were beginning to be equipped en masse with the revolutionary wheellock musket, a very large percentage of them were still carrying matchlocks, which were prone to misfire and were inoperable in wet weather. In contrast, most of the marksmen of the Holy League at Caserta were armed with snaplock and snaphaunce muskets, which used flint to light their powder and could therefore operate in all but the rainiest weather.

The numerical balance was also tilted slightly by the sheer size of both armies, which prohibited sizable portions of each from participating in the combat. Additionally the voracious Spanish appetite for firearms meant that the percentage of musket-carrying soldiers was greater in the Holy league’s army, something of which the Duke of Alba was conscious. Alba gave orders to encircle the Ottoman army despite his inferior numbers in order to concentrate firepower at as many angles as possible. Being enfiladed from two sides, Piyale was blocked from forcing the thin line of Spaniards surrounding his troops back due to the tercio’s defensive mechanism, in which the arquebusiers simply traded places with the pikemen in the event of an enemy closing in. Attempts to outflank the Spanish were further frustrated by the battlefield that had been chosen; attempting to flank Holy league’s northern wing brought the Ottoman sipahis within range of the artillery on the fortifications of Caserta, slowing them significantly and allowing for a counter charge, while an attempt to flank the southern wing was surprised by a tercio in reserve, which closed the gap between themselves and the crescent of tercios, skewering the Ottoman incursion between them. With such a massive number of troops forced into a shrinking space, the distribution of the different Ottoman units was lost and different companies became enmeshed with one another, complicating the issuing of orders from the Ottoman leadership.

Watching his well-ordered and intimidatingly large army be inexplicably balled up into a mass of bloody corpses, Piyale ordered a retreat. Unfortunately for the Spanish, as the tide was turning, a shrapnel from an exploding cannonball cleaved Alba’s breastplate, piercing his chest. Nevertheless, the Spanish commander continued giving orders as he bled internally, and, after the tercios threatened to waver over the news of Alba’s injury, order was restored when word spread that he was still alive. After 8 hours of combat, Piyale left the field. Thousands were massacred in the retreat, and even more were massacred who retreated misguidedly towards the nearby Valle de Maddaloni instead of southward toward Nola. The Duke of Alba, the King of Spain’s most faithful servant, would live only long enough to see the immediate outcome of his final master stroke, and would expire from his wounds that night.

While he had intended to fall back to Avellino and leave a garrison there to cover his retreat, Piyale had falsely expected disarray in the Christian camp with the death of the Duke of Alba, and had to force a more hurried retreat farther southeast when the vanguard of the army of the Holy League under Emanuele, the duke of Calabria, gave full pursuit. Benevento, Lucera, and Foggia all had to be abandoned, and Piyale deposited garrisons in Potenza and Melfi to hold the Appenine passes against further encroachment by the Holy League. As Emanuele of Calabria settled in with his troops outside the walls of Potenza, uncertainty overtook the leaders of the Holy League. Piyale Pasha and Occhiali were still both alive and uncaptured, all of Apulia and Lucania were still firmly in Ottoman control, and Ottoman ships still regularly ferried supplies across the Strait of Otranto. For many, it seemed that the most realistic option would be to acknowledge the quandary of the situation and cede Apulia or perhaps Sicily to Mehmet III in exchange for peace, but the idea of a permanent Ottoman foothold on the Italian Peninsula or its islands was too unsettling for most of the Holy League and simply unbearable for Juan Pelayo and the princes of Italy. The Venetian delegates - many of whom having spent a considerable amount of time in Konstantiniyye and in Mehmet III’s presence - were knowledgeable of the atmosphere in the High Porte and considered it unlikely that Mehmet III would even be willing to settle for Apulia or Sicily. The Venetians were convinced that the Ottoman Sultan would never offer conciliatory terms unless the combined military might of his empire was jeopardized. Therefore if Southern Italy were to be be completely purged of the Turks some external factor would be needed to precipitate the collapse of Piyale’s campaign or at least place it in an completely unworkable position.

While the many signatories of the Holy League understood that a large-scale naval encounter with the Turks was both inevitable and necessary, the Spanish grand admiral Álvaro de Bazán was adamant that the Ottoman navy be struck with an overpowering force as soon as possible, no matter the situation on land. Nothing less than a complete victory at sea and the destruction of the bulk of the Ottoman fleet - if not its entirety - would suffice. As it stood, despite the victory at Caserta, the combined armies of the Holy League simply lacked the numbers to fully eject the Turks from the Italian Peninsula, especially if resupply across the Adriatic remained possible. A sudden and devastating end to Ottoman naval supremacy would leave between 30,000 and 40,000 Ottoman troops (and no less than 7,000 janissaries) stranded in Southern Italy, cut off from any viable supply route. What was more, Bazán warned that if the Turks be allowed to withdraw even a sizable fraction of their forces across the Adriatic in retreat, they would bring back with them the experience gained by the Ottoman officers and soldiery in Southern Italy. The lay of the land, its terrain, its native populace and their language, its seasonal weather, and the layout of its fortifications would find its way back to Rumelia alongside thousands of prisoners and slaves and whatever plunder they could afford to carry. In short, unless the Turks were properly trapped in Apulia, then the valuable lessons they had learned in Southern Italy could be properly studied within their own borders, meaning that the Italian Peninsula would remain in peril of a more coordinated and adaptive Ottoman invasion in the future. Bazán’s plan gained the traction it needed from the Genoese and Venetian representatives (who had an obvious interest in wiping out the Ottoman navy), and the matter was decided with the approval of Pope Pius V, who offered a blank check of 10,000 ducats to pay for the procurement of ships and seamen.

Pope Pius V

Genoese ships were secured easily enough, but the Venetian navy was at anchor in the Venetian lagoon and therefore was cut off from the rest of the ships of the Holy League by the massive Ottoman navy hovering around the Strait of Otranto. With nearly 300 ships at their disposal, the Ottoman navy could not be challenged without the renowned naval power of the Most Serene Republic. When Doge Alvise Mocenigo allowed his name to be added to the document swearing a Holy League at Rome in 1572, the High Porte treated this as a declaration of war by the Republic of Venice and prepared to move against the Venetians in Dalmatia and wherever they could be found in the Adriatic, bypassing the much closer Crete in order to strike close to the city of Venice and force the republic to accept terms of peace as quickly as possible. This meant that any movement by Venetian warships was bound to be quickly confronted by the Ottomans in order to keep the naval forces of the Holy League separated. When a Venetian fleet numbering 72 galleys sailed southward from Venice in late 1574, it was soon met by an Ottoman fleet at Termoli, where the Venetians unexpectedly lost 16 ships and retreated in defeat, much to the relief of the Ottomans and the disappointment of the Holy League. However, despite strict instructions from the Venetian Senate not to risk any excessive damage or danger to the Republic’s fleet, Barbarigo - in a moment of compassionate determination - ripped up the orders commissioned to him from the Senate and pledged his fleet to converge on Messina with the other ships of the Holy League, no matter what chances they had of victory. Pushing his rowers hard to cut across the Adriatic and descend the Dalmatian Coast, Barbarigo anchored at Ragusa, where - in typical Venetian fashion - he sold any ships that were undermanned or needed to be scuttled. From Ragusa, Barbarigo rode the southwesterly current along the Apulian Coast toward Otranto.

With the Strait of Messina as the only significant waterway guarding Ottoman activities in the eastern half of the Mediterranean that remained in Ottoman hands, Piyale Pasha gave emergency orders to Occhiali to withdraw whatever forces he could from Calabria and Sicily and defend Messina and Reggio to the last man. Occhiali - who was a corsair first and a loyal subject of the Padishah Sultan second - was more concerned about his ships. As the supervisor of all naval activity beyond the Strait of Messina, Occhiali was much more privy to the goings-on in the Western Mediterranean and the buildup of the many fleets of the Holy League. With 67 galleys and galiots at anchor in Messina, Occhiali knew his fleet would be easily overwhelmed if the Holy League descended on him in full force. Occhiali ascertained that the Holy League lacked the numbers to simultaneously relieve Naples (obviously their priority) and retake Messina, an assumption that turned out to be correct, and he was likewise correct to assume that the naval forces of the Holy League would try to force a battle that envelops as much of the Turkish fleet as possible, and therefore he needed to keep his ships in close proximity to the Ottoman navy’s center of gravity. Occhiali therefore had good reason to believe that the Holy League would not be able to take advantage of an open Strait of Messina for at least half a year, and relocated his fleet to Taranto in outright defiance of the Kapudan Pasha’s orders. Without Messina, the Ottoman front in Sicily started to unravel. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, Damat Ibrahim Pasha, and their Turkish officers were powerless to prevent mass desertions, particularly among their North African auxiliaries, who boarded any available ships sporadically to secure passage back to the ports of the Barbary Coast that were not in Spanish hands. The two Turkish commanders were incensed as they were forced to fill in the vacuum left by Occhiali’s unapproved departure, stretching their numbers thin across Syracuse, Catania, and Messina. With almost 200 hostile ships fast approaching Messina, this city had to be abandoned as well, leaving the Ottoman army stuck in the southeastern corner of Sicily, entirely unsure of what to do next.

As the vast majority of Ottoman military traffic had been busy crossing the Strait of Otranto back and forth for the last 4 years, it was no mystery where the site of confrontation would eventually be, however, in the mad flurry of galleys, galleons, and regular supply ships choking every route of the Central Mediterranean, ships were being sighted everywhere and it became near impossible for either side to pinpoint the exact location of the bulk of their adversary’s fleet. Receiving additional ships from València and Palma de Mallorca, Luis de Requesens departed from Cagliari with 42 ships and Álvaro de Bazán departed from Tunis with 47, both en route to Palermo where they picked up an additional 15 ships; Mathurin Romegas and the Knights of St. John rounded up their galleys from Djerba, Monastir, and the Grand Harbor of Malta - 26 in all - and passed Syracuse on their way to Messina; Gianandrea Doria led 24 ships from Genoa and 8 ships from Tuscany-Romagna out of Porto-Vecchio in Corsica to Fuimicino in Lazio, and from there along the coast to Messina; heading from Ragusa, Agostino Barbarigo had 46 ships in tow, and the elderly captain Sebastiano Venier trailed him from Ancona with another 18; last but not least, Pope Pius V had funded 12 galleys of his own, captained by Marcantonio Colonna and Paolo Orsini and joined by another 4 ships which were financed by private French investors, and had his fleet join with Doria at Fiumicino on the way to Sicily. In total, the Holy League had brought together 242 ships - 20 galleasses, 22 galleons, 28 galiots, and 172 galleys. Encouraged by the Ottoman abandonment of Messina (and unable to sufficiently resupply in the empty city), the ships of the Holy League pushed onward, hoping to catch the Ottoman fleet unprepared. Pushing towards Otranto, the Holy League’s fleet skipped over the Gulf of Taranto, where the fleet of the feared corsair Occhiali lay in wait. Ecstatic at the success of his trap, Occhiali put to sail and followed the rear of the Holy League’s fleet at a distance. When the fleets of the Holy League and the Ottoman Empire finally met 10 kilometers from the port of Otranto, both sides had been flanked: the Christians from the south by Occhiali, and the Turks from the north by Barbarigo.

The Battle of Otranto

Against the Spanish center, the line of Piyale Pasha’s lieutenant Hassan Veneziano scored first blood by landing a shot right on the main mast of the massive galleass San Casiano de Tánger. However, the Spanish galleass used the momentum of its collapsing mast to swing about and deliver an 80-cannon salvo right into the cluster of galleys surrounding Hassan’s flagship. Intense fighting between the galleys, galleasses, and galiots commenced while the galleons lagged behind. After 2 hours of bloodshed, the dreaded circumstances arose and an easterly wind sprung up, driving the galleons into the midst of the battle. When it came to mano-a-mano confrontation between a Turkish galley and a Christian galley, the Turks prevailed consistently, in part owed to their continued usage of bows alongside firearms. While bows were considered obsolete by 16th century European navies in comparison to the arquebus, a standard Turkish bowman could fire 10 to 20 arrows in a minute (which could penetrate plate armor), which was a considerable advantage at close quarters compared to the 2 shots an arquebusier could make in the same timeframe. However, as at Caserta, the tactics and hardware of the Ottoman military proved to be outdated in a handful of ways that proved critical. The archetypal Ottoman-Barbary galley was once the terror of the Mediterranean - sleek, fast, and piloted by experienced seamen. These values still held up, but the mobility and firepower of such galleys paled in comparison to some of the vessels they found themselves pitted against. The primary source of trouble came from the galleons; they lacked rowers who could effect quick re-positioning and bursts of speed and, of course, could ram their opponents, but, without the need for oarsmen, more space was opened up in the design of the vessel for a greater number of marines and, more importantly, a greater number of larger artillery pieces. While their movement was almost entirely at the mercy of the wind, the galleons were effectively impossible for standard galleys to approach due to their superior firepower, hull strength, and higher freeboard - the latter of which left the topdeck of the galleys extremely vulnerable to the galleon’s gunners when in close range. The only feasible strategy that the Ottoman galleys could find in respect to these hulking vessels was to hope and pray that the wind did not pick up in their advantage and that they were kept as far away as possible, or were prohibited by shallow waters or crushed one at a time by overwhelming force. Significant money had also been poured in by Spain and the other powers of the Holy League to produce an outsized number of massive galleasses, some of which held as many as 200 cannons.

The sudden entry of almost two dozen galleons - bristling with guns - was devastating. One particular Portuguese galleon, the Elefante, repulsed the boarding attempts of no less than three galleys at once, all three of which it proceeded to sink. The Ottoman center was split in half, leaving one half of it between the Spanish from the south and the Venetians from the north. Occhiali’s flanking maneuver fared much better, destroying at least 20 ships, but this too was reversed when the Venetians were able to join the fight on the southern flank. When Occhiali’s lieutenant Sinan Reis routed without order, Occhiali himself attempted to flee the bloody waters. A great deal of importance was placed on killing or capturing this Italian renegade, whose very existence was an affront to the Italian Christians who pursued him. No less than four ships were sunk or disengaged as they pursued Occhiali off of Cape Leuca, until a well-aimed chain shot decapitated the elderly corsair at his shoulders. Found drifting in the crimson waters were golden chalices and candlesticks pillaged from churches as far away as Sorrento. The crusading frenzy long outlasted the fighting. Hundreds of bobbing Turkish bodies were drawn up by the victorious sailors, who chopped off the heads, ears, noses, hands, and feet. These mutilated remains were then loaded into their cannons, and fired over the walls of Otranto - the most unsettling way for the shocked Turkish garrison to learn that the massive naval battle had been lost.

After Otranto, the Ottoman army’s supply of powder, shot, and - most importantly - food all began to diminish rapidly, and were only replaced in any measure with great difficulty. Within a few months the Apulian and Lucanian countryside was stripped bare of any foodstuffs, and the looming risk of mass starvation menaced the Turkish troops. Mass desertion on land and mutinies at sea to secure ships for passage back across the Adriatic became commonplace, and a semblance of discipline was only restored after grisly public executions and floggings became equally commonplace. With only 22,000 men he could reliably assemble, Piyale moved north from Matera to meet the Holy League near Altamura. As the opposing armies lined up across from each other, Piyale dismounted, drew his saber, and cut down his horse in front of his troops, letting them know that there would be no retreat. Exhaustion and dissent among the Turks won the day for the Christians, and, true to his earlier symbolic gesture, Piyale ordered no retreat, and was captured alive and forced to sign a treaty of surrender (which he possessed no authority to sign) on behalf of all the Turks still in Italy. Mere weeks later, approached by an 8,000 man army led by the viceroy of Sicily, Carlo d'Aragona Tagliavia, the Ottoman forces in Syracuse and Catania surrendered in exchange for guarantees of safe passage back to Tripoli.