Oh, it's an obscure name -- but she was on Trump's shortlist. Here!This might be my ignorance here, but - Meg Ryan as OTL's actress Meg Ryan? If so, I'd love to know what caused this butterfly.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TLIAW: Camelot Lost

- Thread starter Enigma-Conundrum

- Start date

I think her name in the post should be changed to Margaret in order to avoid anymore mixups.Oh, it's an obscure name -- but she was on Trump's shortlist. Here!

There's several ways this statement can be interpreted without the proper context.This reminds me of Neal Deal Coalition Retained

them's fighting wordsThis reminds me of Neal Deal Coalition Retained

Deleted member 145219

Just with how the party coalition’s are.There's several ways this statement can be interpreted without the proper context.

Ah, that makes much more sense, thanks for the clarification!Oh, it's an obscure name -- but she was on Trump's shortlist. Here!

Deleted member 145219

You know, I wonder if I meant to say No Southern Strategy.Ah, that makes much more sense, thanks for the clarification!

46. Bill de Blasio (D-CT)

46. Bill de Blasio (Democratic-CT)

January 20, 2021 -

“We need an inspiring vision of equality that resonates in the hearts, minds, and souls of all Americans.”

January 20, 2021 -

“We need an inspiring vision of equality that resonates in the hearts, minds, and souls of all Americans.”

Bill de Blasio’s admirers and critics seem to only agree on one thing. Both of them see him as the personification of a New America. To his supporters, this is a hopeful leader on white horseback charging valiantly ahead for a bright new future. To his opponents, this horse is not white but pale, its rider no hero but a harbinger of terminal decay for the nation and its people. The jury remains out on whether de Blasio is the former, the latter, both at the same time, or something else entirely.

Whatever the verdict on his tenure, Bill de Blasio the man has his roots firmly planted in the New Deal Consensus. His father Warren Wilhelm Sr. was an army man who lost his leg to an enemy grenade in Okinawa and his mother Maria de Blasio was an editor at the Office of War Information. With victory declared and Wilhelm discharged from the hospital, Wilhelm and de Blasio soon married and continued their lives as employees of the federal government. But their Georgetown home would be rocked by McCarthyism, with both called to their regional Loyalty Board with accusations of subversion - after all, Wilhelm had studied the Soviet economy earning his Harvard masters’ and de Blasio was an active union member. The investigation, which began in 1950, would dog the family at every opportunity as subordinates and colleagues issued all manner of allegations ranging from Wilhelm’s “ultraliberal thinking” at Harvard to de Blasio’s editing OWI propaganda to be favorable to the Soviets to more outlandish claims like the couple’s attendance of a Red Army orchestra. The family would ultimately relocate to Connecticut in 1953, with Wilhelm moving to the private sector as an analyst for Texaco and de Blasio to the Italian consulate. There the family would remain throughout the 1950s, relieved to have returned to New England. In 1960, Maria would unexpectedly become pregnant with her third child at forty-three. Despite worries of complications due to her age, in May 1961 Warren Wilhelm Jr., nicknamed Bill, was born into what he would describe as “the classic American dream.”

Much like the America of the 1960s “Years of Rage,” the classic American dream would not remain that way. The Red Scare had changed Warren Wilhelm Sr., who viewed the accusations as an ultimate insult. Though de Blasio’s older brothers remembered their father’s good days, for Bill family Red Sox games and playing catch with his father gave way to a distant and occasionally unfaithful man who drank two martinis after work then fell silent. As the years went on, two martinis became six martinis and the distance between Warren Wilhelm Sr. and his family only grew. In 1970, Maria de Blasio filed for divorce from her husband, citing “cruel and abusive treatment” over the psychological toll his behavior and abject refusal to seek therapeutic help had caused the family. At the tail end of the divorce process, the increasingly-isolated Warren Wilhelm Sr. drove to a motel and committed suicide. In the note delivered to his mother and brother, Wilhelm wrote of the happiest times of his life, including his service in the Army. No notes were delivered to his sons.[1]

Life went on even through the shocks of his family fracturing. Maria de Blasio’s family, southern Italian immigrants who owned a Manhattan dress shop just one quick train ride away from the family’s Norwalk home, became increasingly present in Bill’s life. Though he physically resembled Warren Wilhelm Sr., de Blasio soon began to identify more with his mother’s relatives. As he described in an interview during his first bid for elected office, “I felt very close to them. They made me realize how it is to start in a new country with all the odds against them.” As a teenager, Bill de Blasio had identified so thoroughly with his mother’s Italian heritage that peers nicknamed him “Senator Provolone” due to his penchant for politics only being outshone by his intense love for Italian sandwiches[2]. By the time he was graduating high school in 1979, he had asked that he be referred to as Bill de Blasio on his diploma.

Bill de Blasio’s love for politics would lead him to formative moments as well. As a delegate to Boys Nation in 1978, an awestruck Bill de Blasio would be personally introduced to President Jack Gilligan, whom he had proudly volunteered for in Connecticut in his spare time throughout 1976. The second would come a year and a half later. Due to a quirk in the 1979 Higher Education Act Amendments negotiated by the Gilligan administration, people like de Blasio would only receive their adjusted levels of scholarship and tuition assistance starting in the 1980 calendar year. As such, de Blasio chose to delay his admission to university until that January and used the remaining seven months to explore his political interests and, more broadly, travel off the beaten path.

*****

The young American stood off to the side of the Roman road, still in a bit of disbelief about where he was and the parade he was seeing.

Bill had wanted to travel in the months he had between high school and university. It wasn’t uncommon, especially in the counterculture - not that Bill really thought of himself as some beat kid or anything, though his mother would argue he looked the part. It wasn’t like he was planning on going to Kampuchea or anything! Regardless of those protests, he had taken some money he had cobbled together working his tail off to fly across the Atlantic. In time, he would see the hits: he’d go to the UK for Longleat ‘79 and seen some of the best the British kings of rock had to offer, from the Rolling Stones to Joe Strummer to the Flowers of Romance to even Tony Blair’s glitzy solo that propelled Ugly Rumours from an opening act to their eighties stardom; he’d waltz across from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia the way a keen student of history would; he’d even spend some decent time in the Alps backpacking to his heart’s content and getting away from it all. It was wonderful, but it all came second to Italy.

Italy was different.

Sure, where Bill stood at this very moment was well-known: it was the Via del Corso, one of the main arteries of Rome. His family was from the south, and in time he’d be there too, but he knew he had to see the great city of empire on his way. It didn’t hurt that the beginning of his summer trip intersected neatly with Republic Day. The grand parade through Rome, a civic-military celebration of Italian culture and resilience, was a sight to behold on any day.

But this wasn’t any day either. This was Italy in 1979. The Communists’ electoral victory that previous autumn, in a NATO nation no less, had shocked the world. It seemed a direct repudiation of all things Cold War - here Berlinguer talked of moving past the need for blocs, leveling his criticism towards imperialist meddling of all stripes - condemning Soviet troops in Prague equally alongside America’s low-level mission in the Congo - and focusing on building a better world within the west. To Bill and a million other young American leftists, this was the resolution to the burning contradiction that fueled the Cold War.

Most of the troupes in the parade were the usual. Military regiments and marching bands, dancers and artists, everything of the culture he loved. But Bill noticed the labor regiments too, the union chapters and working people who made Italy function day to day. He noticed the red banners and partisans on parade as well. It was something truly unique, a celebration of the Italian Republic and freedom but also a celebration of this sort distinctly thrown by the current government - the communist government.

Then Bill saw them. Plain, simple, in the middle of all the political celebration, was a plain open-top white car flanked by a single military police group. Seated atop the back seats, beaming and waving to the crowds packed along the streets, were Prime Minister Enrico Berlinguer and President Giovanni Leone. Berlinguer, the wiry little sparkplug of a man whom western leftists had rested their hopes and dreams on; Leone, the old-school Christian Democrat and heir to Alcide De Gasperi. It was the Compromesso Storico in human form. It was proof.

Awestruck, Bill grinned as the two men drove by, briefly making a shadow of eye contact with Berlinguer. He broke out the pocket notebook he had been carrying with him, a personal journal of his travels. He began to write, then and there.

“At Festa della Repubblica, I noticed something very different from anything I had experienced. What Berlinguer, what the Communist Party had done, was weave together the musical tradition, the artistic tradition, the intellectual tradition, and the political tradition into one beautiful harmony…”

*****

Soon after, de Blasio returned to the United States to attend Georgetown University, where he would graduate with a masters’ in international affairs in 1985. Soon after, he would quickly find work at the Assisi Center, a human rights advocacy organization founded by Fr. Robert Drinan. Though he traveled throughout the Americas with Assisi, he most notably spent weeks at a time in Argentina organizing humanitarian relief with the Montoneros, a group banned from US aid by a Collins administration compromise due to their communist sympathies yet a favorite cause of western leftists in opposition to the country’s outright fascist dictator José López Rega. Where before Bill de Blasio had molded his worldview in his experiences with the domestic and international left such that, according to a uni roommate, “he’d mention FDR, Karl Marx, and Bob Marley in the same sentence,” in Argentina belief turned into practice as de Blasio helped firsthand in their self-professed struggle to build a freer and fairer life for all Argentinians. An activist’s work abroad was never finished, though, and soon enough de Blasio wished to return home from the trenches. Though he contemplated multiple options, after a brief stint in Boston working in Mayor Kennedy’s office on his controversial housing revitalization-slash-desegregation initiative, a lucrative job offer as a field organizer for Governor Toby Moffett’s 1986 re-election campaign brought de Blasio back to his home state. This soon turned to policy work in Hartford, a place de Blasio was content with until 1989.

Roy Cohn’s victory was anathema to Bill de Blasio. It wasn’t just ideological - though an out-and-out democratic socialist had much to disagree with the arch-conservative Cohn over - but rather a clash of personality. To a man whose family disintegration was a legacy of the poison pushed by McCarthy and Cohn, the idea that a bruised ego like Roy Cohn wished to make America look a bit more like him was infuriating to de Blasio, a capital-m Movement man with little love for celebrity politics. So the young activist, now a senior staffer with Moffett, quickly made up his mind: if Roy Cohn could go to the White House, Bill de Blasio could at least go to the Capitol. But entering into Congress from a position of relative obscurity was a difficult task to say the least. The party regulars had fielded a seemingly strong candidate in Hartford’s Mayor John Droney, a Collinsesque Democrat aligned with the anti-Moffett factions. Furthermore, Moffett himself was far more concerned with his longtime protege and state Attorney General Bill Curry succeeding him in the governor’s mansion, so while support would be sent de Blasio’s way it wasn’t his first priority. Bill de Blasio was on his own in what seemed to be the most difficult race of his life.

Crucially, though, de Blasio’s campaign understood the dynamics of the Rust Belt. The de Blasio campaign quickly built a working theory: as much as the Roy Cohns of the world talked about the unheard conservative masses, similar left-wing voters were not so much unheard as unengaged. The party was focused on the traditional view of a campaign: pick a guy like John Droney who can shuffle to the center in the general and win over some crucial mass of independent centrists. This, of course, wasn’t as much of an option for a leftist like de Blasio, but where the moderates were seen as key de Blasio saw the disaffected and disengaged who needed to be registered and turned out. So they focused on building engagement and registration. The candidate held events at the University of Connecticut with the local SDS chapter, bringing voter registration materials as far as possible. He met with nascent local Queer groups, making clear his strong support for their equality as the issue first grew in salience on the national stage. He eschewed fighting for union leaders’ endorsements in favor of trekking through the union halls and speaking directly to the rank and file, a gutsy move for a spindly young leftist but one that earned him respect once he shed the cerebral rhetoric and talked about plant closures like Windsor Locks’ infamous “Black Monday.” Crucially, though, de Blasio’s guerrilla campaign brought him in contact with Black community leaders in Hartford. The city was nearly one-third Black, and intense fear of Hartford going the way of Philadelphia under Lucien Blackwell led to Droney’s sore-loser strategy of fielding white incumbents as independents in the general to peel off Republican votes.[3] This strategy, while not necessarily ineffective, had only increased simmering resentments, especially when a sanitation strike brought on by Droney’s refusal to negotiate with AFSCME seemed to only see cleanup denied to said communities first. The local NAACP quickly endorsed de Blasio once leadership realized he meant business, then soon after marshaled their resources towards his voter registration drives, seeing the opportunity for future engagement and beating the Droney machinery. The end result was, off the backs of galvanized turnout from students, racial and sexual minorities, and unionized voters, Bill de Blasio had given John Droney his first loss by nearly four percent.

Naturally, Droney immediately moved to implement his own strategy, but an ongoing municipal strike unrelated to the sanitation strikes earlier that year and state Democrats quickly rallying their endorsements behind de Blasio at Governor Moffett’s urging crushed his independent dreams. With that squared away, back and forth it went between de Blasio and his Republican opponent, freshman Representative John O’Connell. At the nadir of the recession, though, O’Connell’s proud backing of Cohn’s economic program and a snappy suggestion that people “just move” if the plant closes down were far more pressing than muddled references to the Montoneros. Amidst a national wave in the House, Bill de Blasio was sent to the halls of Congress for the first time at just 29 years old.

*****

There weren’t words to describe Harar. None that seemed appropriate, at least. None of the people of the United States Congress dared try. But yet, here their mission was. Fact-finding, so the originator of the mission Mickey Leland called it.

But it wasn’t so much fact-finding as awareness-drawing. They knew what was happening in Ethiopia, anyone who was paying attention did. But that sure as hell wasn’t what the American public saw. They were apathetic, they saw Africa as a far-off battlefield of the Cold War hardly worth paying mind to. There wasn’t war in Europe, there wasn’t war on the homefront, there wasn’t even a far-off Asian war like Korea no matter how much Hanoi and Saigon rattled the sabers at each other. Relaxation, peace-minded individuals in both camps called it as they grinned and shook hands at arms control summits, like that famous picture of Martha Collins and Valentina Tereshkova in Geneva. Whether it was called “détente” or “разрядка,” paying attention to Africa would jeopardize the whole theory. Ever since Jack Gilligan had called the last troops home from Angola and Mozambique and the Congo, not so much declaring defeat as settling things where they were with popular fronts here and imagined nations there, it had been calm. Worth ignoring, in the eyes of America.

Heads in the sand didn’t make the truth disappear. The truth was that the Horn of Africa was in crisis. It had started with Haile Selassie, the unconquered lion of the African continent. Beloved he was the world over, the same couldn’t be said for him within an impoverished and slow-to-reform Ethiopia. That was why, amidst a hard-hitting famine laying bare the flaws in Ethiopia’s governance, a near-revolution was only stymied by Selassie’s abdication at gunpoint in 1973. While his grandson Zera Yacob went from Crown Prince to Emperor, he was quickly relegated to figurehead status. The real power rested with the newly sworn-in head of state, General Amon Andom. General Andom was a war hero, perhaps the only man with enough credibility to resolve the ongoing conflict at the time of the revolution. Andom’s reforms brought a tentative peace to Eritrea as an autonomous region of Addis Ababa’s patrimony, calm to a public weary of petty landlords exerting their power over them, and despite his distinctly illiberal rule he was a benevolent dictator, as some western coverage called him.

But not all was well within Andom’s regime. While he was personally popular, the military foundations of his regime quickly developed into something cancerous and toxic, a hodgepodge of junior officers both Marxist and nationalistic in nature. Where Andom negotiated with separatists, they saw them as threats to be crushed. Where he dealt with the Somali Democratic Republic - another hodgepodge of Marxism and third-worldist nationalism - as an equal and a neighbor albeit an unfriendly one, they saw an enemy to be suppressed. Most of all, though, the clandestine Military Council - “Derg” - underneath Andom saw the national hero going soft, weak, even traitorous. Some old hawk had gotten a senile Nikolai Tikhonov’s ear and convinced him to greenlight Soviet aid to the Derg. So it was that, in 1984, the Derg launched a quick, bloody coup, killing Andom where he stood when he refused to “give an inch of his country” for them. The Derg regime was bitterly divided, though. The hardline Marxists’ commander Mengistu Haile Mariam had died fighting to take Addis Ababa, and without his star weak collective leadership ensued. But famine had reared its ugly head once more, spooked separatists dug up their guns in preparation, opposition forces rallied in protest, and the Soviets cut and ran. It seemed the Derg was doomed if something didn’t change, and an internal “anti-bureaucratic reorganization” by Atnafu Abate was what did it. Abate was a bit of an Orthodox traditionalist and nationalist, an oddity among Marxist revolutionaries. But it was what drove him, and as he tossed Tafari Benti the nominal leader to the curb in 1988, he proclaimed a revitalized Ethiopia of the days of yore.

That was when the terror - shibir - began. It was a trickle of news at first. The revocation of autonomy from Eritrea, then Ethiopian troops occupying Ogaden, and so on. Some noticed, most didn’t. More noticed when the Eritreans restarted their war for independence, especially the reports of the sheer brutality of the Ethiopian campaign. But most chalked it up to the horrors of war. Then, finally, the Somalis invaded occupied Ogaden, claiming liberation for their brethren from the Ethiopian boot. Then came the separatists - the Tigrayans and the Ogaden Somalis and the Oromo nationalists - and down came the hammer of the Ethiopian government, dominated by Amhara Christians through and through. Talk of mass killings, of soldiers butchering entire towns over their ethnicity or what god they prayed to, that was just hyperbole, surely. That’s what press secretaries in Washington said when asked why aid money went to Addis Ababa, why Atnafu Abate was received at the White House in one rare instance. Just hyperbole in the fight against communism. The Somali Democratic Republic was a strong Soviet ally in Africa, after all.

It didn’t seem much like hyperbole to Harold Washington as he stood in Harar. The city was temporarily in a safe-zone as the United Nations tried desperately to carve a path to the sea to evacuate refugees, and the fighting between Ethiopia and Somalia had briefly ended in Dire Dawa. It was a rare window to see the fallout. The ancient city, perhaps the holiest site of Islam in Ethiopia, was a burned-out husk, piles of rubble and pillars of thick black smoke as far as the eye could see. Centuries-old mosques torn to stones, the city walls bombed out and shelled by a force of people seeking to break an entire group’s will to exist.

As the Congressional Black Caucus’ chairman, Washington had overseen the group’s advocacy on the topic to some controversy. Why, people asked, wasn’t the CBC talking about the issues faced by Black Americans, like issues of school segregation and police brutality? Washington’s deputy, the young Texan Mickey Leland, offered up his usual poeticisms: “We are as much citizens of this world as we are America. It isn’t just injustice anywhere in America that threatens justice everywhere.” Or, in Harold’s more simplistic terms: “We can walk and chew gum at the same time.” This was really why, though. What they had seen was worth a thousand puzzled expressions from reporters who didn’t get it.

It wasn’t just the CBC as well. The nascent Democratic Values Caucus, a group of leftists in Congress who had decently overlapping membership with the CBC’s younger generations, had also been key in this visit. Mel King, bless the young Bostonian, had facilitated the joint nature of the mission, being something of an ambassador between the CBC and the dissident left even though the older parliamentary types like Charlie Rangel were a bit uncomfortable with tying themselves down ideologically. Washington could see it worked like a charm, though. He saw it in the DVC’s chair, the Wisconsinite priest-slash-Representative Robert John Cornell, gazing out over the same devastation and soberly performing a sign of the cross. Washington was inclined to agree with the sentiment, looking at the same thing Fr. Cornell saw.

What they saw were piles. Those masses outside the city’s ancient walls, masses the representatives and their federal handlers realized with unease were bodies, seemed piled up that way solely because there were too many dead in too short a time to even bother with mass graves. A silence, much like the one on Ethiopia at home, fell over the fact-finders. The silence on Ethiopia would not last in the halls of Congress - the images of the Harar Massacre the fact-finders would bring back would eventually lead to the passage of the Moody Amendment banning arms sales to Abate’s regime, a deal the Cohn administration begrudgingly took as it let the WGI pick up the slack. Even so, by the. nearly 2 million Eritreans, Somalis, Tigrayans, Oromos, and Ethiopian Muslims had died in the purges or the infamous “hunger camps,” another million would die after, and millions more would be displaced. Though respite eventually came for those who remained, none of that could bring the generations lost back.

But at that moment in the hot summer of 1991, that ambassador’s somber talk of “the dead” was interrupted. “Not dead,” a scruffy-bearded man - a kid, really - bearing a nametag sticker with “Rep. de Blasio (CT)” scrawled across it interjected with an enraged tremble in his voice, “killed. Someone did this to them. We helped them do this.”

Harold Washington didn’t need to be psychic to know every single one of his colleagues was thinking the same.

*****

Representative Bill de Blasio was hardly a notable member of Congress. Backbencher would be a more accurate term for him, though it wasn’t one in the United States’ legislative parlance. This wasn’t to say that he was doing nothing, just that what he wished to do was decidedly in the minority in both parties during the highly conservative environment of the 1990s. His advocacy for Ethiopian refugees didn’t stop with just the Harar mission, feverishly fighting for continued resettlement and humanitarian aid that was only occasionally granted. He cast a litany of votes against privatization schemes, such as the successful privatization of the Tennessee Valley Authority and the National Railroad Passenger Corporation as well as Cohn’s unsuccessful welfare reform. He aided significantly in the repeal of PAVA under Cheney, also advocating further protections for Queer rights by the government. All in all, he built up one of the most left-wing voting records in Congress throughout the 1990s.

But it wasn’t just Republicans who de Blasio was a left-wing gadfly for. Throughout the 2000s, he would cause similar issues. Despite his close ties with the Congressional Black Caucus - forged in the fires of Ethiopia and maintained in no small part by his wife Chirlaine McCray, a Black activist-turned-speechwriter for his colleague from New York David Dinkins - he irritated his CBC allies by choosing to back anti-poverty stalwart Senator Elizabeth Edwards in the primaries. His pointing to Jackson’s stances on criminal justice and messy history on Queer rights - Jackson having caused some controversy upon stripping a supermodel of honorary Georgian citizenship he had previously granted upon the revelation that she was transgender, callously claiming “I wouldn’t have given it to somebody whose claim to fame was being transsexual”[4] - did little to smooth over the frustrations of the older generation of Black politicians, especially when the Edwards campaign fell into disarray and sank below the waves.

Come 2001, naturally it was Jackson who was in charge, not Edwards or even de Blasio, and even though he campaigned heavily for Jackson in the general election the reach Bill de Blasio the backbencher had was limited. He helped to draft Biden-Milk, though it made more sense to naturally place Harvey Milk the Queer trailblazer’s name on the final bill. Lobbying for a broader recognition of refugee rights in the Anaya Bill by de Blasio and similarly-minded figures was paid some mind, though it was immaterial when the bill failed to pass anyways. Overall, though, Bill de Blasio was simply one of the handful of dissenters drafting broad proposals that would never see the light of day under the New Democracy. But two changes in leadership would further propel Bill de Blasio’s career.

The first was, naturally, that of Maynard Jackson’s death. Bill de Blasio had grown accustomed to a president he often disagreed with, and he mourned like the rest of America mourned. But this meant Ed Markey was president, and though one might think Ed Markey and Bill de Blasio might find some accommodation as Democrats from the Rust Belt, this wasn’t further from the truth. The reality of the situation was that Bill de Blasio had grown increasingly bitter towards Ed Markey. It had all stemmed from the NRPC privatization debate, it seemed. To Bill, where he had steered all of his energy towards saving the rail lines, Ed Markey had taken his thirty pieces of silver in exchange for the B&M turning a profit. To Ed, Bill de Blasio had been off tilting at windmills while he had been trying to take the world as it was and make the best of it for his constituents. From there, a dozen other petty squabbles had arisen until the Connecticut Italian and the Massachusetts Irishman found themselves at odds fairly consistently.

All of this meant that, when the longtime Democratic Values Caucus leader, Paul Wellstone of Minnesota, retired due to his diagnosis with multiple sclerosis, Bill de Blasio was one of the most notable left-wing firebrands in the Democratic caucus. His election to lead the DVC was hardly a surprise, though it did prompt another round of groaning from the mainline Democratic leadership somewhat tired of dealing with “the most rebellious Democrat in Washington.” Under de Blasio’s leadership, the DVC’s stances grew bolder and louder. When Ed Markey and Nancy Pelosi went to Copenhagen to finish negotiating the Arctic Nations Trade Treaty, Bill de Blasio was one of the first Democrats to announce opposition to an agreement he saw as furthering the shipping-off of New England manufacturing to automating Soviet factories, calling for an end to the arms race as the most valid form of rapprochement. When the White House agreed to continue the regulatory shifts and “efficiency reforms” pushed by Speaker Walker’s Republicans in exchange for his initiatives on the environment, de Blasio campaigned feverishly for the retention of the New Deal order. When Ed Markey called his ideal for Usenet expansion “competitive capitalism,” Bill de Blasio and his compatriots drafted a proposal suggesting outright federal ownership of such vital infrastructure. When Markey signed a compromise between the Republican House and Democratic Senate on GSM civil unions - leaving legalization to the individual states but prohibiting nullification of otherwise valid unions across state lines - Bill de Blasio rallied the DVC to its most pro-Queer stance yet, calling outright for total national legalization. All of this continued over the decade of Ed Markey’s administration, giving administration officials, Gary Hart, Chris Dodd, and all the other congressional leaders innumerable headaches.

But come 2013, Ed Markey was gone and in his place was Roger Goodell. While de Blasio had not devoted much energy to supporting Rick Perry, seeing him as the centrist conscience of an already-centrist administration, Goodell’s victory was significantly worse. The passage of EARTA infuriated the DVC, who de Blasio rallied behind a unanimous condemnation of the proposal as a defunding of vital social services to further the aims of the very wealthy. Pass it did anyways, and even as subtle signs suggested a growing cost-of-living crisis due to the combination of Markey and Goodell welfare streamlining mixed with the severe depletion of state capacity caused by EARTA, de Blasio was once again decidedly in the minority of public opinion as the average American appreciated the tax break more than any rumblings of socioeconomic catastrophe. But he was no longer in the minority of Democratic opinion, and his caucus’ growth in membership despite the overall Democratic flop in the 2014 midterms intrigued the new House leadership. In the beginning of the 2015 Congress, Minority Leader Schumer made an offer to his fellow northeasterner - if de Blasio would step down as leader of the Democratic Values Caucus, Schumer could offer him the ranking member slot on the House Education & Labor Committee. Though it was jokingly dubbed the Hell (HEL) Committee for the sheer antipathy the past four Speakers had held towards the post, de Blasio accepted regardless. Evidently, he saw an opportunity.

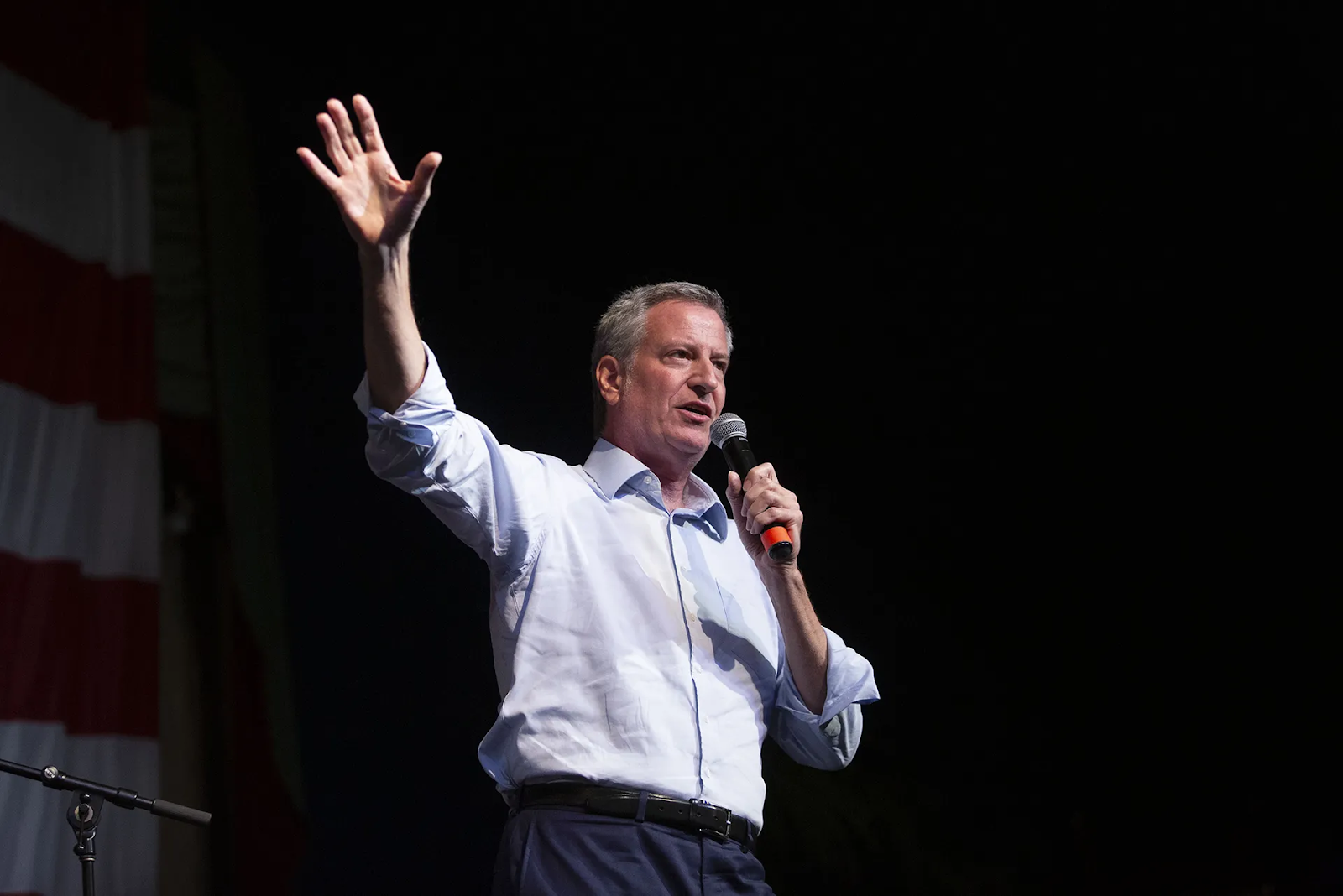

Bill de Blasio wouldn’t chair the Hell Committee until 2019, though. In the meantime, he would continue to do what he had done best for the past 20-odd years: raise hell instead of chairing it. As the AIDS crisis grew, Bill de Blasio became the first sitting member of Congress to volunteer at an AIDS clinic in 2017, working alongside the beleaguered nurses and caught on camera individually sitting with and talking to patients. These moments of compassion drew something rare to him: mainstream attention. Bill de Blasio wasn’t just known only to the most plugged-in politicos and leftist activists anymore. He was in the news, brought on for interviews across the “Big Four” (never SKY, though - talking about him meant talking about AIDS as a Queer disease). It was hardly long-term attention, but he reveled in it all the same, and the praise from the left-wing grassroots for his selflessness in public service fueled his ambitions. Apart from shaving his scruffy goatee in favor of a more “dignified” short-cropped look suited to the cameras, Bill de Blasio would also double down, unveiling a bill not just legalizing civil unions but marriage equality in America from the Capitol steps. The reactions towards this were heated, but they were reactions instead of silence.

Just as his star began to rise ever so slightly, so too did Roger Goodell’s fall end in his muted resignation. Congressional majorities seemed assured, including the first House majority for the Democrats since Maynard Jackson was in office. This gave Bill de Blasio, a backbencher whose contentment with the backbench had finally worn thin, a chance to prepare for his new role chairing the HEL Committee. Re-elected on the largest margin of his career, this preparation paid dividends, and Bill de Blasio sought to redefine what committee chairmanship looked like. Where such work had been capable of being bombastic for decades, first Ranking Member and now Chairman de Blasio took a neglected committee and saw an opportunity to put the entire Republican agenda on trial. Hearing after hearing raised alarms about the cost-of-living spike over the past decade, calling labor leaders and left-leaning economists to back up claims of wage stagnation and spiraling costs for housing, utilities, and simple consumer prices. Fiery arguments with administration officials and corporate executives alike were deeply polarizing as they were covered, but they also saw a significant number of people side with de Blasio as a champion for the millions of Davids against the Wall Street Goliaths. It all seemed to be building to something.

*****

“There’s plenty of money in this country, it’s just in the wrong hands. People in every part of this country feel stuck, or even like they’re going backward, all as the rich get richer. There is inequality our leaders don’t see, there is poverty they don’t see, and there is despair they don’t see. I’m running for President of the United States because we need to end this tale of two countries and remind Washington that it’s only one country - your country.”

The clip cut out at this, with de Blasio beginning to field questions from reporters from the set of microphones he had set up in downtown Hartford. It was back to the NBC Newsroom with that.

Dee Dee Myers spoke first. “So there you have it, America. Bill de Blasio, a veteran Representative from Connecticut, just announced his campaign for the Democratic nomination for president. An unapologetic leftist, he’s seemingly centered his campaign on growing poverty. De Blasio is believed to be a longshot candidate compared to other potential entrants.” Myers turned to her co-anchor. “John?”

Her co-anchor, the longtime newsman John Kerry, chimed in. “Dee Dee, if I may ask just one question that I believe is on most of our viewers’ minds right now: just who the hell is Bill de Blasio?” Both laughed.

Though prescient in the moment and the NBC Newsroom would move on to more important matters, those words would be laid out neatly on history’s banquet table for Kerry to eat for years to come.

*****

While it was broadly true de Blasio was a dark horse, the Democratic Party didn’t seem to have a clear nominee or dominant force. After a minor internal scandal surrounding the selection process in 2016, the party made the decision to transition fully to “one man one vote” for delegate selection. This, combined with the perceived weakness of the Republican Party, saw a plethora of also-rans slowly consolidate as three main candidates pulled away in the “dark primary” of endorsements, donations, and backroom support. There was Kathleen Falk, a Senator from Wisconsin since 2004 generally well-regarded for her work on family issues and criminal justice; Xavier Becerra, the Governor of California since 2014 made notable by virtue of his standing as the leader of the nation’s largest state (albeit one with a weak governorship and a right-wing history); as well as Andy Beshear, a young dynastic Senator from Kentucky whose main focus seemed to be on economic revitalization, especially in Appalachia and the south more broadly. The main connecting thread between the main candidates, though, was that they all seemed connected to the center-left strain that had dominated the party since 2000, with the distinction being more personality-focused. While this sort of primary was nothing new for the party, it left a lane outside the mainstream open.

This lane was where the de Blasio campaign picked up its steam and evolved from longshot to dark horse. The primary debates had been tradition for decades, but they had previously mostly served to reinforce the polling hierarchy, whether that be due to a strong performance by the frontrunner or the others onstage seeking to blunt momentum from a new candidate. The dynamic of the debates in 2020 was relatively unique. Relatively little focus was afforded to de Blasio compared to the other three “serious” candidates, and as such they seemed more focused on picking each other apart. However, the “equal time” rules adopted for primary and general election debates - directly modeled off the Fairness Doctrine that had driven the news media for decades, even through critics point to the ability for networks like SKY to effectively drive discourse by framing what differing viewpoints were acceptable and unacceptable - gave de Blasio just as much speaking time and ability to respond to questions as his opponents. In every response, de Blasio seemed the only person offering a different vision, though the most memorable line of the night came in his closing:

"Everywhere I’ve gone on this campaign, I see a tale of two cities. I see it when people sleep on the streets in Los Angeles and Philadelphia. I see it in Appalachia, where some people still live in sheds. I see in Connecticut, my own state, where thousands of unemployed factory workers wonder why we sent their jobs overseas. I see it when people dying of AIDS have to wait for months to even be seen because our leaders decided we needed the money more for a tax break for billionaires. Tonight, we’ve heard a lot about how we can do more with less, yet nobody once asked why we have less in the first place. I believe, and I believe that you at home all believe too, that we should act boldly to end the tale of two cities. That’s why I’m here - to fight inequality wherever it exists, and to come together as one country where all are created equal.”

The audience had to be told to quiet down at that, and polls showed Democrats overwhelmingly remembered de Blasio most vividly. However, the real genius of it was in the days following. Early on, the young, tech-savvy leftists working the de Blasio campaign office had figured out that there was vast potential to Usenet campaigning. Previous campaigns had utilized it to great effect, but their focus was traversing the layers of interconnected webrings to drum up small donations and get the word out. It was the de Blasio campaign that realized early on that there was a developing political undercurrent in the mass communications infrastructure of the Usenet, especially one for people who felt their views weren’t represented by the old mainstream. In short, the left wing of this seemed like a perfect base not just for donations but for people, of attention in an engagement-based environment and dedicated campaign volunteers.

As more and more people spread word of mouth and Usenet traffic on left-wing circles only grew, the momentum only grew. Videos of de Blasio’s debate moments, of the HEL hearings with executives and labor leaders and economists all backing up his points with simple clarity, all circulated with encouragement from the campaign. A 60 Minutes interview with de Blasio and his wife and children brought a wave of genuinely positive coverage, the image of a mixed-race family sitting around a modest suburban kitchen table talking frankly about their day-to-day lives coming off as deeply relatable compared to a millionaire president and dynastic opponents in the Democratic primary, no matter how much noise was made about his thirty-year career in the House. Concerted campaigning to minority-oriented spaces used to connect unheard communities only increased the energy. This connection was only furthered by de Blasio and his wife frankly addressing their unique relationship (Chirlaine McCray saying "In the 1970s, I wrote about my life as a Black lesbian, and in 1991, I met the love of my life and married him”) and the campaign being the only one to frankly discuss issues of lingering discrimination compared to the lip service offered by the rest of the party. Combined with his decades-long ties to Black, Chicano, and Queer activist groups, the endorsements and donations flooded in soon after.

The end result was a rapidly-growing grassroots momentum, something a fair bit of the Democratic Party was slow to notice. The crowds at his rallies had grown significantly, with tens of thousands of people turning out for rallies all across the country. “BDB FOR USA: THIS IS YOUR COUNTRY!” signs had proliferated from South Side Chicago to the Rio Grande Valley to college campuses in rusted-over cities. Nearly a hundred thousand people showed up in Boston for the largest of these rallies, but yet the party never quite thought it was even possible. Media profiles comparing de Blasio to Jack Gilligan and FDR were interspersed with panicked talk of his radical vision, a too-late attempt to smother the fire. A series of further debates only cemented his strong performances, even if the other candidates were ready for de Blasio’s momentum and tried to parry his bold talk on poverty. On Primary Day, Bill de Blasio was the odds-on favorite, but even so his entire campaign was shocked after winning just under 60% of the vote.

Though some party leaders talked about potentially denying de Blasio the nomination at the convention in direct violation of the new rules, there was little appetite for it, and Speaker Schumer’s personal intervention on de Blasio’s behalf shut the entire process down. Furthermore, de Blasio quickly pivoted to the selection of a running mate, settling on a truly unexpected yet mollifying choice - Senate Majority Whip Mary “Tipper” Gore of Tennessee. By virtue of her position in party leadership Tipper Gore wasn’t the biggest fan of Bill de Blasio, but her husband - “Reverend Al” Gore, a prominent Southern Baptist preacher of Jim Wallis-inspired humanitarian evangelicalism - was perhaps her closest political advisor and had been vital in encouraging the Appalachian populist leftwards over time. So it was that Bill de Blasio went to Madison Square Garden to accept his nomination in a convention so lively that even the archconservatives at the New York Post begrudgingly admitted that “to millions of Americans, Bill de Blasio is a voice of hope.”

*****

Karl Rove pinched the bridge of his nose and cut right to the chase. “Who the fuck came up with that meeting, Rick?”

Rick Wilson, the campaign strategist for President Scott’s re-election campaign sat on the other end of the cameras of the teleconference from the Republican veteran, clearly prepared for the onslaught. “Look. Karl. Eric Adams was polling twenty percent against us-Eric Adams! That nut! He hasn’t even been in Congress for years and he was at twenty points against an incumbent! We had to do something-”

Rove’s next words were a roar, a sound distinctly unfamiliar from the pudgy po-faced campaigner. “AND YOU JACKASSES GAVE DANNIE GOEB FIFTEEN! ALL BECAUSE YOU PUT RICK SCOTT IN A ROOM WITH THE FUCKING OAKLAND RAIDERS!”

“Now look Karl, they won the Super Bowl, and we were thinking with the general election in mind-” Wilson protested.

Rove’s face was beet-red, and he had no intention of stopping. “Don’t interrupt, you good-for-nothing clown! Don’t you remember that meeting I” - at this Rove thumped his chest - “ put together with Harv Atwater? Limbaugh’s guys were our path to winning! But no, you had to shuffle to the center, you had to make Rick Scott look like some sort of enlightened moderate. And how’d that go for you?” Rove didn’t even need an answer. “Oh right, their fucking quarterback asked the President of the United States about over-policing, and he didn’t have an answer!”

“Don’t remind me,” was all an aghast Wilson could muster.

“The Raiders are city-owned, dumbass! The city of Oakland! Do you know anything about how they recruit players? Have you EVER seen a white person wearing a Raiders jersey?” Wilson grimaced a bit at such casual racism from Rove, but if Rove noticed he certainly wasn’t stopping. “They beat the Pioneers last Super Bowl, goddammit! The Memphis Pioneers! The whitest fans in the NFL! I’m impressed, Rick. You managed to make Rick Scott look like a racist monster while simultaneously making sure the actual racists would never vote for him.”

Wilson finally interjected. “A lot of moderates are spooked by de Blasio. We were trying to do a bit of image repair with Markey voters. Make us not look like the enemy. 40% of the Democrats didn’t vote for de Blasio. Limbaugh’s dead, it’s not like Independence Democrats will be voting for him. They have one option - us.”

Rove didn’t buy it. “Well now I can tell you they just won’t even show up. I was going to be reasonable, but you’re done, Rick. I know you know POTUS called me earlier today, yanked me out of semi-retirement to take over the campaign. He also told me I could choose if I kept you on or not. I've chosen, get the fuck out of my sight.”

Rick Wilson sat, mouth agape.

Rove acted as if he didn’t see him. “Fuck, I thought we could even win Pennsylvania if we played it right. Fuck!”

*****

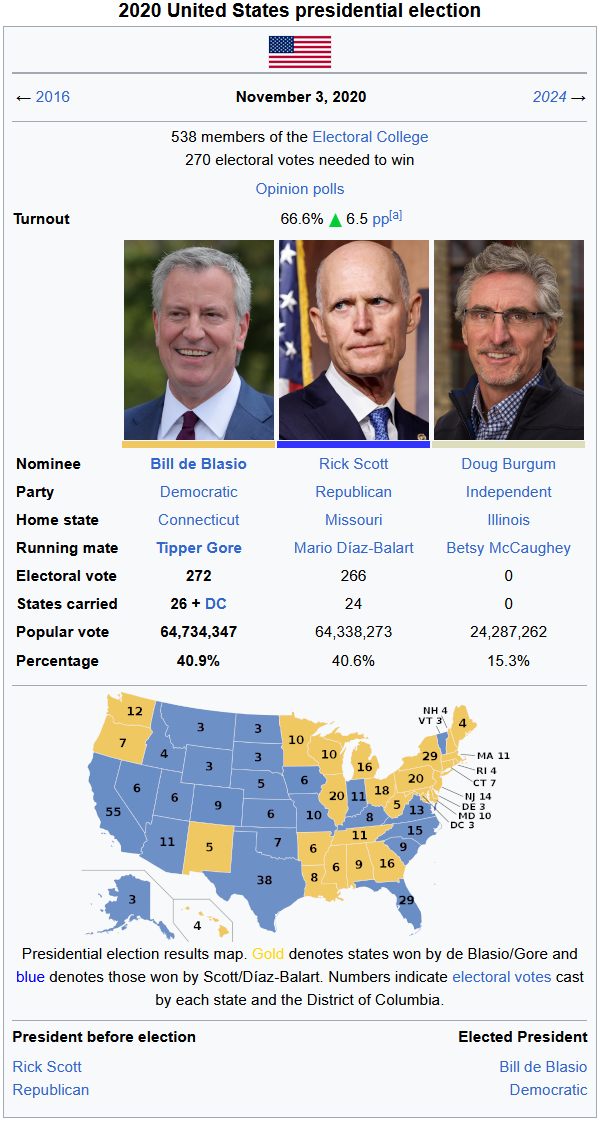

For a brief moment, to de Blasio supporters - “BDBros” on the Usenet - it seemed like he would usher in a new era for America. He was winning by solid margins, no small feat given his rise from obscurity to a presidential nomination. But it seemed that the real trial would be the general election. Rick Scott was not popular for a myriad of reasons, and the primaries reflected that - losing near forty percent between challengers both left and right. He seemed like an uninspiring, ineffectual hardliner, a business executive more concerned with tinkering with budget cuts and blundering his way through the remainder of the term than dealing with a moment of serious societal reckoning in America. Compared to the left-wing firebrand known for his hopeful presence, it seemed like an easy choice.

But plenty of people were disillusioned with politics as usual as well, and that was where the first wrench came in - Doug Burgum. Burgum was a well-known figure: in the 1980s he left his cushy consulting job in Chicago, used what savings he had and money he could borrow, and founded Burgum Systems. Starting as an early information systems pioneer modeled heavily off of early Chilean budgeting systems and soon branching out into secure telecom banking technology, Burgum Systems quickly grew into a major player in the nascent Chicago tech sector. In 2005, Burgum Systems masterfully rebranded itself to break into the newly-demonopolized Usenet, becoming BurgSys, an early provider of linked web-hosting software for personal use. Though not necessarily a computer-manufacturing giant like HP under Steve Wozniak (who made that year’s TIME Person of the Year), the timing made Doug Burgum a very rich man. He would channel his money into occasional political activities, building a profile as a strong leader especially on environmental conservation. As national political disillusionment grew, in late 2019 Burgum hatched a plan: he would run for President on his own as an independent. He would spend the next few months gearing up a shadow campaign, recruiting former Republican Senator Betsy McCaughey of New York as a potential running mate and formulating a detailed platform. When Bill de Blasio officially took the nomination that June, Doug Burgum officially launched his campaign a week later.

After his initial Tonight Show interview, the polls began to indicate something of a shift. Burgum had stressed a sort of centrist populism, a focus on low taxes for the middle class, technologically-driven policy including “American-made boots on Mars by 2030” and combating climate change with innovation, electoral reforms, and broad social reforms focused on decentralization and individual liberties. This, naturally, came off as quite popular to the most disaffected voters, and a number of previously-undecided voters indicated their preference for him seemingly overnight. Furthermore, Independence candidate and right-wing activist Colonel Allen West had none of Limbaugh’s personal flair, leaving a party mostly unified behind one bombastic showman floundering and shifting a number of Limbaugh 2016 voters to Burgum’s camp off the sheer appeal of a “Washington outsider.” Quickly, polls indicating twenty, twenty-five, even thirty percent for the tech mogul coated the race, moving from a likely Democratic victory to a confused mess.

Both major parties had their own reactions to the Burgum campaign. His coalition seemed primarily driven by young urban professionals, disaffected culturally conservative southern Democrats, and a handful of progressive - especially minority - Republicans. For de Blasio, he was a great punching bag who could make Rick Scott look like a joke contender. As such, his attacks quickly refocused on the notion of a billionaire spending hundreds of millions of dollars to buy his way to the White House as well as his support for EARTA and similar “austerity politics,” as de Blasio dubbed the post-Cohn era of limits during the primaries. For Scott, he was to be ignored at all costs. Scott would be a third-rate contender if Burgum was taken seriously, and he needed to ensure that “Burgumania” - as supporters jokingly dubbed the sudden polling surge, becoming a slogan Burgum himself would use - focused primarily on Democrats who disliked de Blasio. As such, the goal was to win back disaffected Republicans. Though the shuffle to the center in the primary failed disastrously, after Karl Rove took over the new plan was simple. Scott’s “Rose Garden strategy” focused on demonstrating him as a calm, competent leader ready to tackle the issues in a way the two wildmen were not. Everything from hosting NATO leaders at Camp David to reaffirm commitments to a non-political appearance at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Houston to even a humanizing interview with Sarah Heath where he discussed his lower-middle class childhood helped to dispel some notions about the incumbent, and the idea of steady leadership as the economy picked up seemed more and more appealing.

And then phase two of Rick Scott’s comeback began: an all-out assault on Bill de Blasio. While there had been rumblings about his past in the primaries, most of his opponents had held off for fear of damaging their credibility with the left when they were nominated. The White House and their allies in the press had no such qualms. The barrage of attacks began slowly, raising questions about de Blasio’s work with the Montoneros and alleging it was far more political than previously thought. Given the recent election of ex-Montonero commander Mario Firmenich as the President of Argentina in 2018, the idea quickly took off that de Blasio was sympathetic to militant leftist groups, and every headline about Firmenich’s strongman behavior only opened the wound further. Then came the references to his time in Italy, his parents’ grilling as suspected communists, and quotations from past early campaigns. In a 1989 interview to a University of Connecticut student paper, de Blasio described his ideal for society as “democratic socialism,”[5] and upon its rediscovery by conservative media outlets Republican surrogates feigned outrage and innocently asked if there was much difference between BDB and the KGB. Furthermore, in 2000 radio interview, he responded to a question about corporate influence in politics with “I am tempted to borrow from Karl Marx here. There’s a famous quote that ‘the state is the executive committee of the bourgeois’ and I use it openly to say, ‘No.' I actually read that as a young person and I said, ‘That’s not the way it’s supposed to be.’”[6] The line “I am tempted to borrow from Karl Marx here” became the introductory line to an aggressive ad buy by the RNC, one that seemed to resonate very deeply with latent anti-communist attitudes in the American public.

Some of the errors were unforced. Bill de Blasio only half-dismissed his “democratic socialism” as “youthful idealism” while also complaining that “an intellectual interest in communist theory” was being taken out of context. This prompted a number of sighs from Democrats, leading to even Senator Gore to resolutely declare herself “not a socialist” in an interview. During a rally with the UFW in southern California, de Blasio made matters worse with the choice to shout “¡Hasta la victoria siempre!”[7] The clip of him invoking Che Guevara’s slogan was soon aired on repeat all over the national news, a line that wasn’t particularly noteworthy to the crowd he invoked it to but was far more polarizing nationally, especially in the Hispanic community. There was a significant divide between Mexican-American Chicanos and Hispanic Americans, with the latter often having emigrated to the United States as a result of Cold War-style instability in their home countries. Memories of the FLN insurgency in Chiapas during Mexico’s Dirty War (incidentally where Guevara died in 1975), Fidel Castro’s government, Floyd Britton’s longtime RAM regime in Panama, the “Tupac Amaru” militias in Bolivia and Peru, and FARC guerrillas in Colombia were dredged up in an instant and egged on by Hispanic surrogates like Cuban-American Vice President Mario Díaz-Balart on the campaign trail. The conservative portions of the media grew so comfortable attacking him that an image of de Blasio eating pizza with a fork and knife while campaigning New York City[8] was a full page cover issue of the New York Post as if it was a major scandal.

All of this built up to, by October, what seemed to be a genuine recovery by Scott to a total three-way race. Negotiations over whether Burgum - who had multiple polls indicating him as the frontrunner - should be included in the debates, were quite long, stalling them such that only one was ultimately held instead of the customary two. Ultimately, Burgum was included, and a twist of fate - and an ankle - would be his undoing. Playing basketball with campaign staff the night before, Doug Burgum broke his ankle and was taken to a hospital. Though he was cleared to attend - and the podium would hide his cast - the painkillers he had to take ultimately altered his focus. Throughout the debate, the billionaire seemed loopy and inattentive, blinking slowly and asking the moderators to repeat the question twice in a row before giving a rambling answer. On foreign policy it was especially bad, with Burgum notably claiming that his investments in Yugoslavia prepared him to negotiate with the Soviet Union, a country very much outside of Soviet influence. No matter the post-hoc clarifications about Burgum’s painkillers and broken ankle, it was so legendarily awful that MADtv’s presidential debate sketch featured Sam the Eagle of Muppets fame portraying Burgum due to his stilted demeanor and sharp eyebrows alongside human sketch comics as de Blasio and Scott.

With Burgum’s collapse complete - only retaining about half of his numbers at his peak - it seemed virtually anyone’s game between Scott and de Blasio. De Blasio had been believed to have won the debate by most respondents polled, but economic reporting had also gotten more positive as a boon for Scott. For a brief, hopeful moment for the RNC, it seemed like maybe they could pull it out, that Karl Rove’s last hurrah had led to the de Blasio campaign crashing and burning under the weight of their candidate’s words and deeds, returning their rightful leadership to them. But it wouldn’t come to pass. On October 30th - “Mischief Night” in the Northeast - a Black fourteen year-old in Newark was placed in a chokehold and killed by a police officer for the heinous crime of running from his friend’s house after pulling a prank. The incident was captured on video, and memories of countless others - from Detroit in the 1980s to Oakland and Baltimore in the 1990s to Houston and St. Louis in the 2000s - saw a reaction like no other. Protests quickly sprung up all across the country, activist groups quickly sourced funding for any and all legal fees for the family, and the national conversation about so many other things was quickly put on halt. It was made worse when journalistic sleuthing revealed that the officer in question had been shuffled from municipality to municipality over multiple complaints against him for extreme violence, retained by the “lowered standards” involved in the hiring surges of the tough-on-crime 1990s and 2000s, and that his particular path was a racially-motivated patrolling expansion as part of the over-policing epidemic. With scarcely three days to Election Day, the onus was on the candidates.

Bill de Blasio’s approach came first. It was a quickly put-together vigil the night after, hosted by a handful of Black churches and community organizations in Newark. That night, he went to the crowds of people in Newark and delivered what may have been the single finest speech of his entire political career. It was simple and yet deeply emotional, focused strongly on his own family. It described when they clearly traveled as a family ans how his children were routinely harassed as if they were trying to rob their father instead of spending time with him. It described run-ins between aggressive police and his own children, the lecture on this topic he and his wife had given them around their old kitchen table about what to do when talking to police, and how “no parent should ever have that fear that their children won’t make it home safe because of the people sworn to protect them.” In a single address, de Blasio touched on a community’s grief, its fury, and its pain with his own, making clear that not only was this unforgivable and horrendous but also all too common. The rioting that was all too common in these cases - the kind that saw Dick Cheney send the national guard into Baltimore to “restore order” in 1998 - didn’t happen in Newark that night, and while ascribing that all to de Blasio is deeply inaccurate in hindsight there certainly were wide-eyed proclamations that it was his doing in the moment.

In contrast, Rick Scott’s approach was memorable for all the wrong reasons. Throughout his career in politics, he had routinely proclaimed the same phrase: “we must stop all efforts to re-imagine policing.” He had said it again and again to uproarious applause, but now that reputation was against him. He opted to organize a personal meeting with the family of the teenager to frankly discuss the issue with them and to express his sincerest regrets. This conversation was curt and cordial, but while the boy’s mother spilled emotionally about how preventable this all was and how it should have been prevented, President Scott looked at his watch. It was a brief glance, one that nobody he was talking to brought up, but to the cameras and those who remembered his years of unabashedly pro-police rhetoric it might as well have been a sign of total and utter disinterest with the entire conversation. The backlash was fierce and intense, with altered images mocking Rick Scott as being disinterested in all manner of important things - from the Hindenburg crashing to the Soviet moon landing to even a Hague trial with Rick Scott on the stand - spreading across the Usenet. As Karl Rove ruefully put it in the following weeks, “we would have won if he had taken his watch off.”

An eventful election season had come and went, and election day had come with little expectation. The polls indicated a close race. Doug Burgum was still a prominent player, but Burgumania’s death on the debate stage had effectively reduced his support to those diehard Burgumaniacs, a relatively evenly distributed electorate. It seemed for a brief moment that Scott could pull off the greatest comeback since the last Missourian to hold the office, but as results came in it seemed clear that the nation was in for a much longer night. The early states all acted as expected - Indiana quickly painted blue, Kentucky too close to call, Virginia and South Carolina blue, Georgia yellow (albeit with a number of rural Democrats and urban Republicans placing Burgum in second, a trend repeated across the yellow South). What was so curious was Vermont. Vermont had always been a blue state - it had never once voted Democratic. But there it was, uncalled even after everyone early but swing-state Kentucky was done. Though its streak would be maintained off the backs of rich New Yorker retirees, the high percentages for de Blasio out of Burlington were out of place and the hour-late call very odd. Pundits took note when de Blasio took swingy New Jersey fairly early on, tying it to the events of the past week and wondering about a potential electoral college sweep for de Blasio. This was quickly dashed as usual suspects painted themselves blue and yellow, the Great Lakes stubbornly yellow and the West ancestrally Republican despite Burgum as the same potential spoiler. Republicans cheered when Missouri and Texas were called for Scott, then Democrats celebrated when Pennsylvania and Tennessee swung for de Blasio. By nearly midnight on the east coast, de Blasio led the popular vote with only three states remaining uncalled: Kentucky, New Mexico, and New Hampshire of all places. Scott was at 258 electoral votes and de Blasio 263. Then, just after 1:00 am, the call came in Kentucky: Rick Scott had clinched the state and its eight electoral votes. Democrats groaned and the mood soured at de Blasio headquarters, their best shot of the remaining states at taking the White House gone. After all, both of the remaining states were a brutal pull for Democrats.

Then it happened, one after the other. New Mexico came through first. Despite the Hispanic overperformances by Scott, UFW organizers and Chicano sweated blood into canvassing the state, registering tens of thousands of new voters and forcing polling stations in Bernalillo County to stay open late. This effective revival of the sophisticated La Raza Unida turnout machine that broke the California Republicans back in the 1990s ultimately resulted in a 8,705-vote margin. It was a well-earned relief for the Democrats, but it wasn’t enough on its own as the count stood 268-266. Then the real shock came from the Rust Belt. New Hampshire had last voted Democratic for FDR in 1944. It was seen as practically ungettable, a state too entrenched in the right-wing tradition of upper New England. But New Hampshire had rusted over more than most, suffering massive job losses as mills closed down and factories moved from Manchester to Mostar. Furthermore, as one of the oldest populations in the nation, its usual “Live Free or Die” libertarian bent was often overridden by strong support for Social Security and Medicare. The defunding of hospitals in New Hampshire under Rick Scott and talk of cutting Social Security benefits combined with de Blasio’s talk of bringing jobs back to the dilapidated Granite State inspired something. People had called the campaign well and truly insane for taking the campaign bus from Portland to Boston, but at 2:38 am Eastern the Rust Belt focus was vindicated when New Hampshire broke a seven-decade streak and was finally called by just 1,626 votes for de Blasio. Over the noise of the greatest political party Hartford had ever seen, the candidate didn’t even notice that Rick Scott didn’t call to concede and wouldn’t until the following night out of bitterness. The candidate was too busy giving a victory speech much like his campaign - improbable yet eminently uplifting. “We have no illusions about the task that lies ahead. Tackling inequality isn't easy. It never has been and it never will be. The challenges we face have been decades in the making, and the problems we sought to address will not be solved overnight. But make no mistake, this country has chosen a bold new path, and tonight we set forward together on it as one country.”

With an oath and a speech on a cold Washington D.C. day, Bill de Blasio became the first President of the United States to take the post directly from the House of Representatives since James Garfield in 1880, the third Catholic President after Jack Gilligan and Ed Markey, the first Italian-American to hold the post, and in the eyes of a solid forty-to-forty-five percent of the country the first socialist President of the United States. It was a unique type of polarization unheard of in the modern era for a new president to barely even get a honeymoon period, but then again why would he expect one? Fifty-nine percent of America had not voted for him, and already there was talk of how de Blasio would have to temper his agenda to fit the whims of the Democratic leadership given his status as a “plurality president.”

Nonetheless, de Blasio had no intention of simply rolling over. While the Senate worked on confirming “the most radical Cabinet in history,” de Blasio set about enacting the parts of his agenda that could be done on his own. Within days, a new White House Task Force pledging to be “a Manhattan Project for AIDS treatment” was launched with the aim of coordinating disparate infectious disease research and providing regular updates to the public. New Attorney General Larry Krasner, previously Pennsylvania’s crusading state Attorney General against police misconduct, announced a sweeping review of policing standards around the nation by the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division. A total suspension of all aid to Harayman-backed Islamist militias drew typical fiery rhetoric from the Grand Mufti but significant praise from human rights organizations domestic and international. The first hundred days saw a flurry of action of this sort designed around seizing the moment to really substantively move policy before the realities of Washington kicked in.

The first real legislative push was relatively uncontroversial among Democrats: the repeal of EARTA. Though some had voted for the bill, at this point the harm done had polarized many of them against it. While some wished to use the opportunity to rein in spending, a simple up-or-down vote on a bill to end the austerity experiment and in its place especially restore funding for offices like the IRS to rebuild the ability of the state to collect funds passed on basically partisan lines. This was projected to, with the severe slashes to federal agencies over the past decade, provide a healthy amount of new funding to apply to new projects, including affordable housing and power subsidies to try and combat the very cost-of-living crisis that had seen de Blasio resonate so heavily in the first place.

And this new budgetary situation fed directly into the second goal: infrastructure. Though reversing privatization was deeply controversial within de Blasio’s own party, there were some areas where there was crossover support. One such area was railroads. Even some old progressive Republicans, like the Delawarean “Lion of the Senate” Joe Biden, were staunchly in favor of passenger rail for the economic benefits alone. Biden’s aid in drafting a bipartisan proposal with Senator Walz establishing the “Ameritrak” corporation as a national interstate railroad corporation as a competitor was instrumental in getting the proposal out of committee and through the halls of Congress. The other core section was electrification and digitization. Though the Usenet had spread far and wide, its accessibility was still somewhat limited, with connectivity and access often out of date or even missing in many rural areas. A platform point that de Blasio was fond of mentioning was seemingly inspired directly by New Deal rural electrification, with its focus most heavily on ensuring reliable Usenet service for all. This was a goal that virtually all Democrats agreed upon, but the devil was naturally in the details. The Markeyite focus on regulatory competition was far more appealing to a handful of Democrats. Meanwhile, de Blasio himself wanted direct federal ownership a la the TVA as an inch towards the undoing of privatization more broadly. This was a non-starter for a number of moderate Democrats, and they made their grievances known. The end compromise, negotiated over a series of weeks and near-walkouts, was an adaptation of an old alternate proposal for the TVA. The government would administer the new Federal Utilities Service Authority (FUSA), but it would be run for-profit as a market competitor to private institutions with the goal of paying its own debts off. Whatever the case, the end result was the Infrastructural Modernization Act, passed by Congress along virtually partisan lines and signed into law around the end of the summer, with projects to begin during the next calendar year.

Try as they might, the de Blasio administration could not simply focus on domestic issues, and it would be some foolish thing in the Middle East as always that forced their hand. In this case, it was Jerusalem. Jerusalem had been one of the main sticking points of the end of the Levantine Wars, only barely resolved for fear of nuclear hellfire. The joint administration scheme had worked rather well when it was Israel and Palestine, but upon Palestine’s annexation to the United Arab Republic the situation had devolved. Prime Minister Avigdor Lieberman, a barely-reformed ex-minister of the Kahane government, had withdrawn from the joint administration of Jerusalem in 2016. His citing that the Israeli government had made a deal with Palestine and not the UAR saw the two states nearly come to blows in the streets of Jerusalem, only being stopped by the United States’ threat to cut off the deal they had made in 2014 over the nuclear situation. The end result was a complicated agreement where the city would be divided, but free movement would be allowed between West and East with hard borders outside city limits on the doctrine of “no more Berlins.” Fresh off a crushing re-election victory, Prime Minister Lieberman sought to cut this Gordian Knot of the Zionist ideal. So it was that, in September of 2021, Avigdor Lieberman sent troops in to occupy West Jerusalem, declaring the city under martial law and expelling all UAR nationals in West Jerusalem. Naturally, this incensed Cairo, who quickly moved to expel Israelis from the East and to close the border fully between the two halves of the city.

The de Blasio administration looked at this and saw a major headache. It was true that Democrats tended to be more sympathetic to Israel - Ed Markey had spent the better part of a decade engaging the succession of Prime Ministers Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, Isaac Herzog, and Tzipi Livni in cautious rapprochement - but as Secretary of State Steve Kerr touched down in the Middle East his goal was simply to prevent a shooting war. A new round of non-military investments in Israel, the unfreezing of further frozen UAR assets ahead of schedule, and the return of a jailed UAR spy were all deeply controversial domestically, but it prevented Cairo’s overtures towards sending troops into West Jerusalem to put an end to the martial law and Tel Aviv’s talk of occupying the whole city. Even so, the conflict didn’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon, especially provoked with Palestinian hardliner Marwan Barghouti’s election as the new President of the UAR in 2022.

Life went on as usual for a bit as 2021 turned to 2022, seemingly. President de Blasio and Treasury Secretary Jeffrey Sachs received a strong welcome at the Group of 25’s first annual summit of his term, even if relatively little of substance was achieved beyond outlining future goals. A first meeting between the new President and new Soviet Premier Sergey Baburin - a much more nationalistic kind of communist - revived internal discussions of policy towards Eastern European satellite states and the Soviet suppression of Central Asian dissidents, especially after the United Nations declared Moscow’s treatment of the Kazakhs violations of human rights. In response the Soviets caused as much trouble as possible in selecting a new Secretary-General that January, forcing it through the longest round of ballots in United Nations history until a compromise choice in the form of acclaimed former Korean President Choo Mi-ae emerged. This process also drew criticism of de Blasio’s seemingly vacillating and weak foreign policy, with experts like Stanford University’s resident Kremlinologist Condoleezza Rice called onto news shows to discuss the flaws in de Blasio’s pragmatism towards the Soviet Union after talking such a big game on human rights. However, this sort of criticism took a backseat when Patrick Leahy, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court for nearly 40 years and a quietly effective liberal whose opinions included abolishing the death penalty and sodomy laws, announced his intent to retire. Already faced with an extremely significant decision to ensure the continuation of such jurisprudence, in Leahy’s place de Blasio and his administration saw an opportunity to make history with their nomination.

The selection of Ninth Circuit Judge and former Assistant Attorney General Pamela S. Karlan was not necessarily surprising but trailblazing nonetheless. Karlan would be the first woman to lead the Supreme Court, but beyond that she was also an openly bisexual woman with a female partner. She would be the first openly Queer person to serve on the court, and her nomination as such sparked further discussions about Queer rights in American society that had never really faded since the AIDS crisis engaged a new generation of Queer people. Karlan’s questioning was intense in a way unseen for SCOTUS nominations in years, but the California judge wittily dispatched much of the worst of it, even snarkily quipping “I’d hate to think you were discriminating against us liberals, Senator” in response to a barely-concealed bit of homophobia from New Jersey Senator Samuel Alito. Even so, her confirmation as Chief Justice saw a 72-32 vote, a number of dissenting votes generally unheard of for a qualified SCOTUS nominee.

With the national conversation firmly turned towards Queer rights, de Blasio saw that moment of the spring of 2022 as the time to push forwards. In a major address from the White House flanked by the First Lady, President de Blasio made clear his total support for a bill legalizing same-sex marriage. This policy had passed in a number of western countries, having been legalized first by Sweden in 2003 and then spreading through western countries, most notably passed within the Anglosphere by Pierre Pettigrew’s government in Canada in 2011 and Harriet Harman’s government in the United Kingdom in 2014. The proposal by de Blasio, whose speech ended with him publicly urging a Congress wholly unaware of his intent to support the proposal, sparked a wildfire in the United States. A number of left-leaning members of Congress quickly announced their support, filing in behind Mark Takano’s proposed bill enforcing legalization of same-sex marriage. Bill de Blasio flew the Queer rainbow flag from the roof of the White House, a move which drove a number of conservatives nuts for reasons they couldn’t quite place. Queer groups bombarded Senators’ offices with protest campaigns demanding their support for the bill. However, the frustration at the way de Blasio had handled the unveiling of his support rankled Congress. Schumer and Walz had built an accommodation with him, getting things sorted out with him and Lamont before sending things to the floor. They had done well on EARTA and infrastructure, and why couldn’t he just have played ball on this one? Angry meetings with leadership over his public snubbing of their wishes to be consulted first saw the proposal nearly shelved, especially with religious groups pushing back hard on the initial Takano proposal. It looked, for a brief moment, like de Blasio had tilted at the wrong windmill.