You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

'the Victorious': Seleucus Nicator and the world after Alexander

- Thread starter ClaustroPhoebic

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

As I wrote in my message, this was just after the alt-First Syrian War, when Antigonus was still alive and kicking (and having a summary of divergences *at that point* would have been useful).The Antigonids are dead and gone ITTL, it is the Seleucids who rule Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus now.

@ClaustroPhoebic, a minor nitpick/suggestion: to disambiguate between those two Antiochuses (Antiochoi?), wouldn't it be more effective to replace that (II) by a nickname? My understanding is that this was the common way to proceed for all those identically-named Hellenistic kings, and moreover this would avoid a potential spoiler. As I understand it, OTL Antiochus I is Soter, while Antiochus II is Theos; while the first nickname is likely preserved TTL, the second one is more likely to change. For inspiration, here is a list of nicknames from OTL: https://www.forumancientcoins.com/moonmoth/hellenic_names.html (“the cutter-up of tuna fish”, really?..).

Impressive post, thanks! However, I am not too versed in the Syrian wars of OTL (neither are, I suspect, most of the readers of your TL), so I don't see how exactly it diverges so far. I just finished reading the alt-First Syrian war part and it seems still very close to OTL, apart from the Celts in Asia Minor; in particular, Macedonia seems to be back on track with the Antigonids. Are there any other divergences I missed?

The Antigonids are dead and gone ITTL, it is the Seleucids who rule Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus now.

It's been a while since I wrote it but off the top of my head:

-Increased Seleucid ties to (and loyalty within) Greece and Macedonia. So, unlike our timeline, the Seleucids actually have supporters existing within the Macedonian court and aristocracy and a somewhat more powerful Athens at their back. Simultaneously, Antigonus' position is weakened in this timeline since he no longer has the prestige from defeating the Gallic invasion

-Better Seleucid control of Ionia, mostly because Seleucus lives longer to cement that control more and the Seleucid kings are passing through more often en route to, and coming from, Macedonia.

-In addition, the Ionian revolt (which didn't take place in our timeline) and subsequent downfall of the early Attalids preventing any real Pergamene emergence

-No Galatia in the way we understand it but an increased integration of Gallic peoples into parts of the Seleucid empire

-Increased Seleucid involvement in Aegean affairs and a wider span of territory over which wars with the Ptolemies will now take place (so not just Asia Minor and Syria but now also the Aegean Sea and Greece).

I could add more but I don't wish to spoil the timeline for you! Also feel free to ask any questions you wish about earlier parts of the timeline, I'll try to answer best I can and help out!

-Increased Seleucid ties to (and loyalty within) Greece and Macedonia. So, unlike our timeline, the Seleucids actually have supporters existing within the Macedonian court and aristocracy and a somewhat more powerful Athens at their back. Simultaneously, Antigonus' position is weakened in this timeline since he no longer has the prestige from defeating the Gallic invasion

-Better Seleucid control of Ionia, mostly because Seleucus lives longer to cement that control more and the Seleucid kings are passing through more often en route to, and coming from, Macedonia.

-In addition, the Ionian revolt (which didn't take place in our timeline) and subsequent downfall of the early Attalids preventing any real Pergamene emergence

-No Galatia in the way we understand it but an increased integration of Gallic peoples into parts of the Seleucid empire

-Increased Seleucid involvement in Aegean affairs and a wider span of territory over which wars with the Ptolemies will now take place (so not just Asia Minor and Syria but now also the Aegean Sea and Greece).

I could add more but I don't wish to spoil the timeline for you! Also feel free to ask any questions you wish about earlier parts of the timeline, I'll try to answer best I can and help out!

An interesting Seleucid site

Mount Nemrut is a very interesting site and it shows a lot about Greek and Persian interactions in Asia Minor. It's not actually a Seleucid site but Commagenian, built by King Antiochus I of Commagene during the 1st Century BCE. That said, as far as I am aware, a fair few of the choices made here to resemble interactions promulgated by the Seleucids and Antiochus himself was the son of a Seleucid princess and grandson of Sames II of Commagene.

As I wrote in my message, this was just after the alt-First Syrian War, when Antigonus was still alive and kicking (and having a summary of divergences *at that point* would have been useful).

@ClaustroPhoebic, a minor nitpick/suggestion: to disambiguate between those two Antiochuses (Antiochoi?), wouldn't it be more effective to replace that (II) by a nickname? My understanding is that this was the common way to proceed for all those identically-named Hellenistic kings, and moreover this would avoid a potential spoiler. As I understand it, OTL Antiochus I is Soter, while Antiochus II is Theos; while the first nickname is likely preserved TTL, the second one is more likely to change. For inspiration, here is a list of nicknames from OTL: https://www.forumancientcoins.com/moonmoth/hellenic_names.html (“the cutter-up of tuna fish”, really?..).

I did consider using nicknames instead of the '(II)' thing but it felt weird to use a epithet for Antiochus which he hasn't been given as of yet. He does have an epithet ITTL as do all Seleucid kings ('Megas' in his case as opposed to 'Theos') but it would've felt wrong to call him 'Megas' when he hasn't yet become king or earned the epithet, especially since the readers haven't yet seen anything from him to earn that name. Hope this helps!

Fun. Interesting foreshadowing here - at the moment it looks like the empire is going to wind up fraying from both ends, as the Eastern and Western satrapies break away, leaving the Seleucids with only the central core. Mind you, Syria plus Mesopotamia plus most of Anatolia is quite the core, particularly with further Greek settlement and development of the cities. There's also the question of when Antiochus III-style expeditions to re-unite the empire cease to be worth the candle and just exhaust the core to claim sovereignty over peripheral regions that can no longer be held.

Interesting map of Antioch - I assume of the OTL Roman city, from the captions?

Given how the politics of Hellenistic kingdoms tended to run, the odds on Dionysus (or someone) attempting to dispose of the boy-king and claim the empire for himself are looking quite high. And why do I think we haven't seen the last of Argeus? There was reference earlier to the Ptolemies getting to Afghanistan, so will one of them try to take advantage of a succession dispute to set him up as puppet Seleucid emperor?

Interesting map of Antioch - I assume of the OTL Roman city, from the captions?

Given how the politics of Hellenistic kingdoms tended to run, the odds on Dionysus (or someone) attempting to dispose of the boy-king and claim the empire for himself are looking quite high. And why do I think we haven't seen the last of Argeus? There was reference earlier to the Ptolemies getting to Afghanistan, so will one of them try to take advantage of a succession dispute to set him up as puppet Seleucid emperor?

My guess would be exactly this: Antiochus III conveniently dies, some noble claims the imperial crown (I don't think we have names for courtiers/generals in the core regions of Syria/Mesopotamia, apart from Diomedes who on the contrary needs the boy alive; I would guess somebody related to his mom Amestris?) claims the imperial crown, Ptolemies remember about Argeus who is suddenly the “legitimate” heir, war begins, satraps proclaim independence (in particular, Macedonians don't accept an “Iranian” family on the throne).Given how the politics of Hellenistic kingdoms tended to run, the odds on Dionysus (or someone) attempting to dispose of the boy-king and claim the empire for himself are looking quite high. And why do I think we haven't seen the last of Argeus? There was reference earlier to the Ptolemies getting to Afghanistan, so will one of them try to take advantage of a succession dispute to set him up as puppet Seleucid emperor?

Fun. Interesting foreshadowing here - at the moment it looks like the empire is going to wind up fraying from both ends, as the Eastern and Western satrapies break away, leaving the Seleucids with only the central core. Mind you, Syria plus Mesopotamia plus most of Anatolia is quite the core, particularly with further Greek settlement and development of the cities. There's also the question of when Antiochus III-style expeditions to re-unite the empire cease to be worth the candle and just exhaust the core to claim sovereignty over peripheral regions that can no longer be held.

Interesting map of Antioch - I assume of the OTL Roman city, from the captions?

Given how the politics of Hellenistic kingdoms tended to run, the odds on Dionysus (or someone) attempting to dispose of the boy-king and claim the empire for himself are looking quite high. And why do I think we haven't seen the last of Argeus? There was reference earlier to the Ptolemies getting to Afghanistan, so will one of them try to take advantage of a succession dispute to set him up as puppet Seleucid emperor?

My guess would be exactly this: Antiochus III conveniently dies, some noble claims the imperial crown (I don't think we have names for courtiers/generals in the core regions of Syria/Mesopotamia, apart from Diomedes who on the contrary needs the boy alive; I would guess somebody related to his mom Amestris?) claims the imperial crown, Ptolemies remember about Argeus who is suddenly the “legitimate” heir, war begins, satraps proclaim independence (in particular, Macedonians don't accept an “Iranian” family on the throne).

Yes, I'm really not an artist so I'm not out here making maps or anything but it was too good a map to not use it and simply too useful for showing the general layout of the city and region. Diomedes is definitely going to play a significant role going forward as is Argeus... as are the Ptolemies but not perhaps quite in the way you think. Think about it from Argeus' perspective, forced to flee as a child and growing up in the Ptolemaic court surrounded by enemies of the Seleucids who all too eager to remind him that Seleucus has taken everything from him; his father, his... second father, his home, his status as prince... All that I'll say for now is that Argeus is about to become a much bigger problem than either Ptolemy or Seleucus is really expecting.

What has happened ITTL with Achaeus, son of Seleucus I, and his family / descendants? They haven't been mentioned anywhere.

So the Doylist explanation here is simply that I haven't included them mostly for my own sanity; it introduces a lot of other people into this family to keep track off and chart. That said, they will be coming in in the next couple of chapters so I haven't just forgotten about them or totally ignored them. For now, I can say that they've generally been around the Seleucid court holding a variety of different positions; generals, satraps, a variety of officer positions etc. I'll try to give some sort of summary in the next chapters because I am aware I've been remiss in not dealing with them until now, I've just been trying to make things easier on myself in terms of plotting and it quickly becomes unmanageable to include everybody.

I have only met Seleucus II for five minutes, and I already see him as a great downgrade lmao. The way you described him reminds me a lot to Viserys I from ASOIAF.

Exited to see what comes next! Oh and by the way with their contacts in India would the Greek start to notice any similarities between their language and Sanskrit?

Exited to see what comes next! Oh and by the way with their contacts in India would the Greek start to notice any similarities between their language and Sanskrit?

I have only met Seleucus II for five minutes, and I already see him as a great downgrade lmao. The way you described him reminds me a lot to Viserys I from ASOIAF.

Exited to see what comes next! Oh and by the way with their contacts in India would the Greek start to notice any similarities between their language and Sanskrit?

Hmmm… interesting question! I would say probably not since I feel like these similarities are difficult to really see or understand without linguistic study. The odd person here and there might notice a few similarities but I doubt there’ll be anything large-scale or institutional. I mean, as far as I’m aware, they didn’t in our timeline.

I feel kinda bad for poor Seleucus, man’s doing his best…

@ClaustroPhoebic, if you want a good mapmaker, PM @Sarthak or @B_Munro...

Good TL, and waiting for more...

Good TL, and waiting for more...

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-One: The Rise of Diomedes

The year is 186 BCE and Seleukeia is burning. Much of the city is already in flames, tens of thousands are dead or have fled the city for the refuge of nearby Babylon as soldiers swarm through the remains of the city looting and killing. At their head is Aristarchus, a member of the Seleucid family and respected general of the eastern frontiers. He has sworn revenge; everybody in the palace is going to die and there is nothing anybody can do to stop it. Inside the palace, Diomedes, 'Hand of the King', hurries to rally whatever defence he can and sends messengers to try and run Aristarchus' siege and get help. Whether he knows it or not, no help is coming; the empire has begun to fracture and beyond the narrow confines of Mesopotamia, it's every man for himself. Back in the palace, King Seleucus IV 'Epimanes' has been confined to his chambers, sustained by a steady supply of food and held under strict guard to prevent anyone from getting to him. After the things the king has already done, everybody knows he wont last long. Still, Diomedes needs him, he needs a king or his head will soon be on the chopping block. Only two men could break the siege now, both currently cutting a bloody swathe through the empire as they converge on the city. On one side, the self-styled Gorgias I a Seleucid general who has recently emerged from the chaos of Iranian politics in the 190s as a powerful figure and, on the other, the undefeated general Argeus I 'Aniketos', King of Egypt.

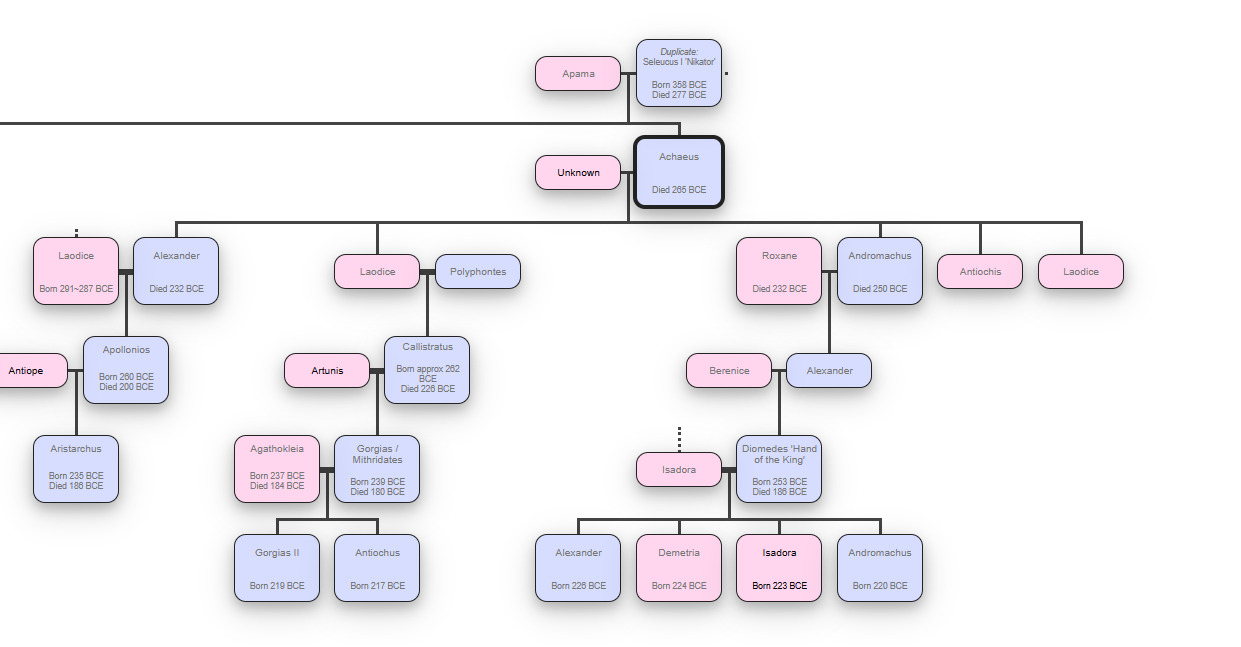

Note: This is a simplified family tree to emphasise the important figures for our narrative and not to provide a comprehensive outlook on the entire Seleucid family.

Everything had gone very very wrong by the 180s, a quite dramatic change over a period of only about 24 years. When we left off with the death of Seleucus III, the empire was still rather stable and intact for the most part but his death, and the accession of his eleven-year-old son Antiochus III. To really understand what happened here, however, we should take some time to step back and look at the rise of one of the most important figures of the age; Diomedes. To understand this, however, we should understand his personal relationship to the royal family itself. See, Diomedes wasn't just an aristocrat but a member of the royal family if only a very minor one. Nor was he alone. See, Seleucus I's second son Achaeus had four children named (confusingly) Antiochis, Alexander, Andromachus, Laodice and Laodice. To make matters even more difficult, his eldest son, Alexander, had married yet another Laodice, the daughter of Antiochus I and sister of Antiochus II. During his lifetime, Achaeus emerged as a very wealthy landowner, especially in Asia Minor, especially after his brother's defeat of the Gauls in the 270s after which Achaeus seems to have come into possession of extra lands around the Meander River. Upon his death in 265 BCE, the lands were largely split between his children with the lion's share going to his sons Alexander and Andromachus but with some lands and wealth being provided as dowries for his daughters.

For his part, Alexander remained active mostly in Asia Minor and was elevated by Seleucus II to be the king's representative in the region in 260 BCE. Upon Seleucus II's death, however, he was quick to change sides to Antiochus II and was rewarded with extra lands and allowed to keep his position. He would oversee most of Asia Minor for the next few decades until his death in 232 BCE. His son, Apollonios has made very little impact on our source evidence save for that he married a Greek woman from Samos and administered his share of his father's lands (which, again, had been split between he and his two brothers: Alexander and Demetrios) ably. His marriage would produce Aristarchus in 235 BCE, a name worth keeping in mind for his significance later on. Achaeus' daughter Laodice (the elder of the two Laodices) married a Macedonian elite named Polyphontes and sometime around 262 BCE gave birth to Callistratus 'Kalos' (not the same Callistratus who would later govern Macedonia however). This Callistratus would spend much of his time around the Seleucid court in Seleukeia and supposedly kept a close friendship as a young man with the poet Sosthenes in the 240s. He would also marry an Iranian woman by the name of Artunis, a marriage which would produce Gorgias in 239 BCE. In the 230s, Callistratus was made satrap of Sogdiana and would remain in this position until 226 BCE when he died and the satrapy was transferred. In 218 BCE, Seleucus appointed his son, Gorgias (then 21) as the new satrap, a position he would hold for some 38 years until his death in 180 BCE. For his part, Gorgias would marry Agathokleia (a descendant of Antiochis, Achaeus' daughter) and produce two sons: Gorgias II, born in 219 BCE and Antiochus, born in 217 BCE.

Finally, we get to Diomedes, the great-grandson of Achaeus by his second son, Andromachus. Andromachus was active in Syria during Antiochus II's first war against the Ptolemies during the 250s, possibly as a sub-commander of some description and was granted lands in the region near Apamea in return for his service. Little is known about his son Alexander except that he was active in the court during the 240s and knew Callistratus 'Kalos' during his time there. His son Diomedes was born in 253 BCE and grew up in Apamea in Syria. At the age of 16, he travelled to Antioch and from there to Greece where he would spend a few years studying philosophy which he is said to have truly hated. At age 21, Diomedes joined the Seleucid court as something of a minor official. A year later, in 231, he was appointed as an oikonomos, a minor financial official of a small region in northern Phoenicia. He excelled and by 229 had been appointed dioiketes (financial officer for an entire region) in Syria itself, a position which put him in direct contact with Antiochus II. His rapid rise was probably just as much a result of his high born status and links to the Seleucid family, but he was also renowned for his financial talents even in his day. Between 229 and 227 BCE, he oversaw an increase in the tax revenue from Syria and was involved directly in the actual workings of the Seleucid financial system, allocating funds for projects and sending commands down the hierarchy as needed. In 228 BCE, he married Isadora, the daughter of the guard commander Sophokles.

In doing so, Diomedes aligned himself more and more with the pro-Macedonian faction under Queen Kleopatra. This was to prove a mistake since the outbreak of war in 227 BCE would precipitate a fall from grace for Diomedes over the next few years. During the Ptolemaic invasion, Diomedes' involvement at court fell to nearly nothing and he largely abandoned his post while Syria was under Ptolemaic occupation. This would lead to claims that he had collaborated with the invaders later in his life but there isn't sufficient evidence to say either way whether or not Diomedes aligned himself with the Ptolemies or not. Regardless, the 220s saw the rise of Ariobarzanes' influence at court and the decline of the pro-Macedonian faction as Antiochus II leaned ever more on his Iranian supporters. His death in 219 BCE sealed the deal and many of the pro-Macedonian aristocracy fell out of power including Diomedes as the Perso-Babylonian faction saw its own power increase between Ariobarzanes and Amestris. This all changed again, however, in 217 when the rebuilding process in Syria provided an opportunity for Diomedes to regain his influence. While Seleucus III was in Antioch, Diomedes travelled personally to the city and, daring to forgo court practice, simply approached the king himself, almost being arrested by Mithridates, the commander of the king's bodyguard since the early 210s, but avoiding arrest by claiming that he could so much as halve the costs of rebuilding parts of Antioch. According to Caiatinus, Diomedes was able to leverage his personal connections across Syria to obtain better prices on supplies and workmen and dramatically reduce the cost (although whether he achieved his 50% discount is unknown).

Regardless, the display was enough to earn him some favour and Diomedes was soon returned to his position as dioiketes of Skyria. At a time of thorough rebuilding in the region, the result was that Diomedes saw frequent interactions with Seleucus who is said to have enjoyed his company and frequently sought him out for recommendations and discussion. All this, of course, despite the reservations of Ariobarzanes and his own faction. Soon enough, Ariobarzanes began recommending that Diomedes be removed from power for being too dangerous, especially given his ties to Sophokles, a known conspirator who had worked with Prince Antiochus and Kleopatra to plot rebellion. Diomedes, however, had a response to this, claiming that his marriage to Isadora was one of passion above reason and offering to divorce her should it make the king more comfortable but asking that he be allowed merely to continue acting as a loyal servant to the king. Accordingly, the two were divorced in 216 BCE but Diomedes did in fact continue to act as dioiketes of Syria. In addition, Diomedes' two sons and two daughters were to be taken to the court as hostages for good behaviour.

In truth, Diomedes emerged from this no worse for wear and, over the next two years, continued to consolidate his own base of power. His focus was largely trying to reorganise the pro-Macedonian faction in the wake of Kleopatra's flight to Egypt in 219 and house arrest in 218 BCE. Astonishingly, Kleopatra would continue to live until 208 BCE, outliving Seleucus III and dying at the age of 71. Her flight to Egypt hadn't entirely destroyed the pro-Macedonian faction but it had fractured it into two. Some supported the possibility of an outright replacement for Seleucus right up until the murder of Demetrius in 215 BCE and flight of Berenice in 213/12 BCE. Diomedes, however, now became the voice of an increasingly popular Macedonian faction which was willing to work with Amestris and Ariobarzanes but championed the cause of Macedonian elites under the rule of Seleucus III and his descendants rather than those of Antiochus. Seeing an opportunity to outmanoeuvre their own enemies, Amestris and Ariobarzanes mostly allowed Diomedes to rally and continue operating until Demetrius' death in 215. See, with the downfall of Demetrius, Diomedes was able to make serious political gains, scooping up the support of many of the active Macedonian elites in the empire and forging a new pro-Macedonian faction. Their first real triumph here was the reconstruction of Antioch which took place almost entirely in the hands of these Macedonian elites and with little influence from the Perso-Babylonian faction under Ariobarzanes and Amestris.

Nor was this a small thing; the entire fabric of Seleucus' new grand city was Macedonian in character and design with reasonably few adaptations from Persian or Babylonian cities in its image. The statement being made was that the Seleucid empire and its kings were still Greco-Macedonian kings first and foremost and that they were rejecting an outright adoption of Persian precedent or infrastructure. Not that Diomedes abandoned these altogether since he himself was famously partial to Persian gardens and, during his regency, would fund the construction of a new garden on the banks of the Orontes known as the 'Antiochian Gardens' after its official patron, Antiochus III. The garden built by Diomedes was extensive, gathering plants from all across the Seleucid empire and even beyond with plants and animals brought from India including elephants and an enclosure which, for a few months, held a live captive tiger. Under better times, Diomedes' garden would have become a wonder in its own right but many of the features, including the fountains which were described by one historian as 'the most beautiful ever constructed' were never finished and the whole thing fell into disrepair under Argeus I. Diomedes' success, even if only ideological, had worked by his convincing the king to grant him increased authority over the hiring of architects, planners, and even construction teams many of which he brought from Greece and Macedonia, especially along the Ionian coast. During this period, Diomedes also spent time with Caiatinus and agreed to send the diplomat several marble statues for his rural villa back in Italy, a fact which demonstrates Diomedes' immense personal wealth.

In 214 BCE, Ariobarzanes died and his faction's power over the throne began to fracture. This stemmed from a steadily growing dislike between Queen Amestris and her father's cousin, Mithridates, then the commander of the royal guard. The exact origin of their distrust is unknown save for that he assumed that he would take command of the Perso-Babylonian faction and attempted to command her, something which she, as queen, deeply resented. In their squabbling, the supporters of Ariobarzanes soon found themselves forced to take sides, caught between the military power of Mithridates and his royal guard and the political power of Amestris. Looking to overcome Mithridates, Amestris turned to Diomedes asking for his help and together, the two hatched a plot. Between them, they forged reports that Mithridates was planning to usurp the throne and then squashed any information to the contrary. Between them Diomedes and Amestris worked to monopolise access to the king and, soon enough, he was only recieving word of Mithridates and his supposed treachery. Mithridates was arrested along with many of the royal bodyguards and executed.

In the aftermath, however, Diomedes was quick with suggestions. There were, he argued, many worthy of the position including, say, Aristarchus, a member of the royal clan and a first cousin once removed of Seleucus no less, a much closer relation to the king than Diomedes himself was. Aristarchus, to his credit, had military experience and may well have fought under Demetrius in the early 210s. While he was no great commander, or even especially clever by any means, he had the backing of Diomedes and enough military experience for the position as well as having spent time at court recently. Regardless, by the end of 214 BCE, Aristarchus was commander of the royal bodyguard and firmly in Diomedes' pocket. With Aristarchus at his back, Diomedes now began dismantling the rest of Mithridates' support network, having several arrested for conspiring with Mithridates in a series of purges in 213 BCE and convincing Seleucus to demote, or fire, several others on the basis of their performance. In their place, Diomedes was quick to institute his own people. Not all of these were Macedonian and, in fact, very few came from Macedonia itself at all. Instead, Diomedes' support network was almost entirely comprised of Greeks and Macedonians living in Syria, many of whom had been there since the time of Seleucus I almost a century earlier.

Attacking Amestris was harder and there was no hope that Diomedes could ever remove her from power. In 213 BCE, he instead began targeting her supporters. Several were arrested as part of the Mithridates purges, largely on forged evidence of their intention to help Mithridates in the coup but his most successful tactic was simply to disgrace them. Scandals of incompetence, impropriety, bribery, and even adultery began to rock the court as official after official was caught out and dismissed. In their place came a whole legion of Greco-Syrian bureaucrats eager to take up the reigns of power for themselves. While Amestris herself kept power, Diomedes effectively disarmed her. While he did so, he made sure to keep her occupied, encouraging the king to send her off on long trips to visit cities and satrapies on the far extremes of the empire. By the time he was done, her own power over the government was neutered and almost every administrative decision was working through Diomedes or his supporters. For now, at least, Diomedes had emerged triumphant. Around 211, Amestris was able to make something of a comeback when she convinced her husband to begin weakening Diomedes for fear that he would launch a coup. Several officials were fired but Seleucus died in 210 BCE before Diomedes could be seriously weakened. With his death and the need of a regent for Antiochus III, Diomedes now stepped in to take control.

The year is 186 BCE and Seleukeia is burning. Much of the city is already in flames, tens of thousands are dead or have fled the city for the refuge of nearby Babylon as soldiers swarm through the remains of the city looting and killing. At their head is Aristarchus, a member of the Seleucid family and respected general of the eastern frontiers. He has sworn revenge; everybody in the palace is going to die and there is nothing anybody can do to stop it. Inside the palace, Diomedes, 'Hand of the King', hurries to rally whatever defence he can and sends messengers to try and run Aristarchus' siege and get help. Whether he knows it or not, no help is coming; the empire has begun to fracture and beyond the narrow confines of Mesopotamia, it's every man for himself. Back in the palace, King Seleucus IV 'Epimanes' has been confined to his chambers, sustained by a steady supply of food and held under strict guard to prevent anyone from getting to him. After the things the king has already done, everybody knows he wont last long. Still, Diomedes needs him, he needs a king or his head will soon be on the chopping block. Only two men could break the siege now, both currently cutting a bloody swathe through the empire as they converge on the city. On one side, the self-styled Gorgias I a Seleucid general who has recently emerged from the chaos of Iranian politics in the 190s as a powerful figure and, on the other, the undefeated general Argeus I 'Aniketos', King of Egypt.

Note: This is a simplified family tree to emphasise the important figures for our narrative and not to provide a comprehensive outlook on the entire Seleucid family.

Everything had gone very very wrong by the 180s, a quite dramatic change over a period of only about 24 years. When we left off with the death of Seleucus III, the empire was still rather stable and intact for the most part but his death, and the accession of his eleven-year-old son Antiochus III. To really understand what happened here, however, we should take some time to step back and look at the rise of one of the most important figures of the age; Diomedes. To understand this, however, we should understand his personal relationship to the royal family itself. See, Diomedes wasn't just an aristocrat but a member of the royal family if only a very minor one. Nor was he alone. See, Seleucus I's second son Achaeus had four children named (confusingly) Antiochis, Alexander, Andromachus, Laodice and Laodice. To make matters even more difficult, his eldest son, Alexander, had married yet another Laodice, the daughter of Antiochus I and sister of Antiochus II. During his lifetime, Achaeus emerged as a very wealthy landowner, especially in Asia Minor, especially after his brother's defeat of the Gauls in the 270s after which Achaeus seems to have come into possession of extra lands around the Meander River. Upon his death in 265 BCE, the lands were largely split between his children with the lion's share going to his sons Alexander and Andromachus but with some lands and wealth being provided as dowries for his daughters.

For his part, Alexander remained active mostly in Asia Minor and was elevated by Seleucus II to be the king's representative in the region in 260 BCE. Upon Seleucus II's death, however, he was quick to change sides to Antiochus II and was rewarded with extra lands and allowed to keep his position. He would oversee most of Asia Minor for the next few decades until his death in 232 BCE. His son, Apollonios has made very little impact on our source evidence save for that he married a Greek woman from Samos and administered his share of his father's lands (which, again, had been split between he and his two brothers: Alexander and Demetrios) ably. His marriage would produce Aristarchus in 235 BCE, a name worth keeping in mind for his significance later on. Achaeus' daughter Laodice (the elder of the two Laodices) married a Macedonian elite named Polyphontes and sometime around 262 BCE gave birth to Callistratus 'Kalos' (not the same Callistratus who would later govern Macedonia however). This Callistratus would spend much of his time around the Seleucid court in Seleukeia and supposedly kept a close friendship as a young man with the poet Sosthenes in the 240s. He would also marry an Iranian woman by the name of Artunis, a marriage which would produce Gorgias in 239 BCE. In the 230s, Callistratus was made satrap of Sogdiana and would remain in this position until 226 BCE when he died and the satrapy was transferred. In 218 BCE, Seleucus appointed his son, Gorgias (then 21) as the new satrap, a position he would hold for some 38 years until his death in 180 BCE. For his part, Gorgias would marry Agathokleia (a descendant of Antiochis, Achaeus' daughter) and produce two sons: Gorgias II, born in 219 BCE and Antiochus, born in 217 BCE.

Finally, we get to Diomedes, the great-grandson of Achaeus by his second son, Andromachus. Andromachus was active in Syria during Antiochus II's first war against the Ptolemies during the 250s, possibly as a sub-commander of some description and was granted lands in the region near Apamea in return for his service. Little is known about his son Alexander except that he was active in the court during the 240s and knew Callistratus 'Kalos' during his time there. His son Diomedes was born in 253 BCE and grew up in Apamea in Syria. At the age of 16, he travelled to Antioch and from there to Greece where he would spend a few years studying philosophy which he is said to have truly hated. At age 21, Diomedes joined the Seleucid court as something of a minor official. A year later, in 231, he was appointed as an oikonomos, a minor financial official of a small region in northern Phoenicia. He excelled and by 229 had been appointed dioiketes (financial officer for an entire region) in Syria itself, a position which put him in direct contact with Antiochus II. His rapid rise was probably just as much a result of his high born status and links to the Seleucid family, but he was also renowned for his financial talents even in his day. Between 229 and 227 BCE, he oversaw an increase in the tax revenue from Syria and was involved directly in the actual workings of the Seleucid financial system, allocating funds for projects and sending commands down the hierarchy as needed. In 228 BCE, he married Isadora, the daughter of the guard commander Sophokles.

In doing so, Diomedes aligned himself more and more with the pro-Macedonian faction under Queen Kleopatra. This was to prove a mistake since the outbreak of war in 227 BCE would precipitate a fall from grace for Diomedes over the next few years. During the Ptolemaic invasion, Diomedes' involvement at court fell to nearly nothing and he largely abandoned his post while Syria was under Ptolemaic occupation. This would lead to claims that he had collaborated with the invaders later in his life but there isn't sufficient evidence to say either way whether or not Diomedes aligned himself with the Ptolemies or not. Regardless, the 220s saw the rise of Ariobarzanes' influence at court and the decline of the pro-Macedonian faction as Antiochus II leaned ever more on his Iranian supporters. His death in 219 BCE sealed the deal and many of the pro-Macedonian aristocracy fell out of power including Diomedes as the Perso-Babylonian faction saw its own power increase between Ariobarzanes and Amestris. This all changed again, however, in 217 when the rebuilding process in Syria provided an opportunity for Diomedes to regain his influence. While Seleucus III was in Antioch, Diomedes travelled personally to the city and, daring to forgo court practice, simply approached the king himself, almost being arrested by Mithridates, the commander of the king's bodyguard since the early 210s, but avoiding arrest by claiming that he could so much as halve the costs of rebuilding parts of Antioch. According to Caiatinus, Diomedes was able to leverage his personal connections across Syria to obtain better prices on supplies and workmen and dramatically reduce the cost (although whether he achieved his 50% discount is unknown).

Regardless, the display was enough to earn him some favour and Diomedes was soon returned to his position as dioiketes of Skyria. At a time of thorough rebuilding in the region, the result was that Diomedes saw frequent interactions with Seleucus who is said to have enjoyed his company and frequently sought him out for recommendations and discussion. All this, of course, despite the reservations of Ariobarzanes and his own faction. Soon enough, Ariobarzanes began recommending that Diomedes be removed from power for being too dangerous, especially given his ties to Sophokles, a known conspirator who had worked with Prince Antiochus and Kleopatra to plot rebellion. Diomedes, however, had a response to this, claiming that his marriage to Isadora was one of passion above reason and offering to divorce her should it make the king more comfortable but asking that he be allowed merely to continue acting as a loyal servant to the king. Accordingly, the two were divorced in 216 BCE but Diomedes did in fact continue to act as dioiketes of Syria. In addition, Diomedes' two sons and two daughters were to be taken to the court as hostages for good behaviour.

In truth, Diomedes emerged from this no worse for wear and, over the next two years, continued to consolidate his own base of power. His focus was largely trying to reorganise the pro-Macedonian faction in the wake of Kleopatra's flight to Egypt in 219 and house arrest in 218 BCE. Astonishingly, Kleopatra would continue to live until 208 BCE, outliving Seleucus III and dying at the age of 71. Her flight to Egypt hadn't entirely destroyed the pro-Macedonian faction but it had fractured it into two. Some supported the possibility of an outright replacement for Seleucus right up until the murder of Demetrius in 215 BCE and flight of Berenice in 213/12 BCE. Diomedes, however, now became the voice of an increasingly popular Macedonian faction which was willing to work with Amestris and Ariobarzanes but championed the cause of Macedonian elites under the rule of Seleucus III and his descendants rather than those of Antiochus. Seeing an opportunity to outmanoeuvre their own enemies, Amestris and Ariobarzanes mostly allowed Diomedes to rally and continue operating until Demetrius' death in 215. See, with the downfall of Demetrius, Diomedes was able to make serious political gains, scooping up the support of many of the active Macedonian elites in the empire and forging a new pro-Macedonian faction. Their first real triumph here was the reconstruction of Antioch which took place almost entirely in the hands of these Macedonian elites and with little influence from the Perso-Babylonian faction under Ariobarzanes and Amestris.

Nor was this a small thing; the entire fabric of Seleucus' new grand city was Macedonian in character and design with reasonably few adaptations from Persian or Babylonian cities in its image. The statement being made was that the Seleucid empire and its kings were still Greco-Macedonian kings first and foremost and that they were rejecting an outright adoption of Persian precedent or infrastructure. Not that Diomedes abandoned these altogether since he himself was famously partial to Persian gardens and, during his regency, would fund the construction of a new garden on the banks of the Orontes known as the 'Antiochian Gardens' after its official patron, Antiochus III. The garden built by Diomedes was extensive, gathering plants from all across the Seleucid empire and even beyond with plants and animals brought from India including elephants and an enclosure which, for a few months, held a live captive tiger. Under better times, Diomedes' garden would have become a wonder in its own right but many of the features, including the fountains which were described by one historian as 'the most beautiful ever constructed' were never finished and the whole thing fell into disrepair under Argeus I. Diomedes' success, even if only ideological, had worked by his convincing the king to grant him increased authority over the hiring of architects, planners, and even construction teams many of which he brought from Greece and Macedonia, especially along the Ionian coast. During this period, Diomedes also spent time with Caiatinus and agreed to send the diplomat several marble statues for his rural villa back in Italy, a fact which demonstrates Diomedes' immense personal wealth.

In 214 BCE, Ariobarzanes died and his faction's power over the throne began to fracture. This stemmed from a steadily growing dislike between Queen Amestris and her father's cousin, Mithridates, then the commander of the royal guard. The exact origin of their distrust is unknown save for that he assumed that he would take command of the Perso-Babylonian faction and attempted to command her, something which she, as queen, deeply resented. In their squabbling, the supporters of Ariobarzanes soon found themselves forced to take sides, caught between the military power of Mithridates and his royal guard and the political power of Amestris. Looking to overcome Mithridates, Amestris turned to Diomedes asking for his help and together, the two hatched a plot. Between them, they forged reports that Mithridates was planning to usurp the throne and then squashed any information to the contrary. Between them Diomedes and Amestris worked to monopolise access to the king and, soon enough, he was only recieving word of Mithridates and his supposed treachery. Mithridates was arrested along with many of the royal bodyguards and executed.

In the aftermath, however, Diomedes was quick with suggestions. There were, he argued, many worthy of the position including, say, Aristarchus, a member of the royal clan and a first cousin once removed of Seleucus no less, a much closer relation to the king than Diomedes himself was. Aristarchus, to his credit, had military experience and may well have fought under Demetrius in the early 210s. While he was no great commander, or even especially clever by any means, he had the backing of Diomedes and enough military experience for the position as well as having spent time at court recently. Regardless, by the end of 214 BCE, Aristarchus was commander of the royal bodyguard and firmly in Diomedes' pocket. With Aristarchus at his back, Diomedes now began dismantling the rest of Mithridates' support network, having several arrested for conspiring with Mithridates in a series of purges in 213 BCE and convincing Seleucus to demote, or fire, several others on the basis of their performance. In their place, Diomedes was quick to institute his own people. Not all of these were Macedonian and, in fact, very few came from Macedonia itself at all. Instead, Diomedes' support network was almost entirely comprised of Greeks and Macedonians living in Syria, many of whom had been there since the time of Seleucus I almost a century earlier.

Attacking Amestris was harder and there was no hope that Diomedes could ever remove her from power. In 213 BCE, he instead began targeting her supporters. Several were arrested as part of the Mithridates purges, largely on forged evidence of their intention to help Mithridates in the coup but his most successful tactic was simply to disgrace them. Scandals of incompetence, impropriety, bribery, and even adultery began to rock the court as official after official was caught out and dismissed. In their place came a whole legion of Greco-Syrian bureaucrats eager to take up the reigns of power for themselves. While Amestris herself kept power, Diomedes effectively disarmed her. While he did so, he made sure to keep her occupied, encouraging the king to send her off on long trips to visit cities and satrapies on the far extremes of the empire. By the time he was done, her own power over the government was neutered and almost every administrative decision was working through Diomedes or his supporters. For now, at least, Diomedes had emerged triumphant. Around 211, Amestris was able to make something of a comeback when she convinced her husband to begin weakening Diomedes for fear that he would launch a coup. Several officials were fired but Seleucus died in 210 BCE before Diomedes could be seriously weakened. With his death and the need of a regent for Antiochus III, Diomedes now stepped in to take control.

Last edited:

And this is an opening. I was expecting the empire to go through some tough times, I wasn't expecting this.Chapter Thirty-One: The Rise of Diomedes

The year is 186 BCE and Seleukeia is burning. Much of the city is already in flames, tens of thousands are dead or have fled the city for the refuge of nearby Babylon as soldiers swarm through the remains of the city looting and killing.

This confused me. Presumably Antiochus II wasn't plotting rebellion against himself and this refers to the Antiochus-who-never-was, Seleucus III's younger brother, who disputed the succession on Antiochus II's death?Regardless, the display was enough to earn him some favour and Diomedes was soon returned to his position as dioiketes of Skyria. At a time of thorough rebuilding in the region, the result was that Diomedes saw frequent interactions with Seleucus who is said to have enjoyed his company and frequently sought him out for recommendations and discussion. All this, of course, despite the reservations of Ariobarzanes and his own faction. Soon enough, Ariobarzanes began recommending that Diomedes be removed from power for being too dangerous, especially given his ties to Sophokles, a known conspirator who had worked with Antiochus II and Kleopatra to plot rebellion.

Word missing here? Presumably a reference to Kleopatra?In truth, Diomedes emerged from this no worse for wear and, over the next two years, continued to consolidate his own base of power. His focus was largely trying to reorganise the pro-Macedonian faction in the wake of her flight to Egypt in 219 and house arrest in 218 BCE.

Yup, holding power from beyond the grave is always a challenge. Refers to the Persian-Babylonian faction rather than Ariobarzanes personally?In 214 BCE, Ariobarzanes died and his personal power over the throne began to fracture.

Just call me Littlefinger. I like the way this chapter is called "The Rise of Diomedes" when we already know it will end with three rebel armies converging on the capital, all of whom want his head on a pike. Diomedes, you done messed up. But I'm looking forward to finding out exactly how.For now, at least, Diomedes had emerged triumphant. Around 211, Amestris was able to make something of a comeback when she convinced her husband to begin weakening Diomedes for fear that he would launch a coup. Several officials were fired but Seleucus died in 210 BCE before Diomedes could be seriously weakened. With his death and the need of a regent for Antiochus III, Diomedes now stepped in to take control.

(Also, the last chapter is missing a thread mark)

Well I was right Seleucus was a trash king and the actions of Diomedes don't bode wore for the future of the dinasty.

I do have one question why was he so brutal against Seleukeia, wouldn't this be a bad move politically?

Then again as his actions will end up with 3 armies besieging him that absolutely want him dead, it isn't much of a surprise.

Also, did anything of cultural significance in the city got destroyed?

I do have one question why was he so brutal against Seleukeia, wouldn't this be a bad move politically?

Then again as his actions will end up with 3 armies besieging him that absolutely want him dead, it isn't much of a surprise.

Also, did anything of cultural significance in the city got destroyed?

And this is an opening. I was expecting the empire to go through some tough times, I wasn't expecting this.

This confused me. Presumably Antiochus II wasn't plotting rebellion against himself and this refers to the Antiochus-who-never-was, Seleucus III's younger brother, who disputed the succession on Antiochus II's death?

Word missing here? Presumably a reference to Kleopatra?

Yup, holding power from beyond the grave is always a challenge. Refers to the Persian-Babylonian faction rather than Ariobarzanes personally?

Just call me Littlefinger. I like the way this chapter is called "The Rise of Diomedes" when we already know it will end with three rebel armies converging on the capital, all of whom want his head on a pike. Diomedes, you done messed up. But I'm looking forward to finding out exactly how.

(Also, the last chapter is missing a thread mark)

There are a few typos which have created some confusion I think so I'll head back and fix those. Yeah I meant Seleucus' brother, the would-have-been Antiochus III had he not lost his head. Also yeah it was meant to be Kleopatra, I'd rewritten the paragraph during editing and missed this whoops!

Well I was right Seleucus was a trash king and the actions of Diomedes don't bode wore for the future of the dinasty.

I do have one question why was he so brutal against Seleukeia, wouldn't this be a bad move politically?

Then again as his actions will end up with 3 armies besieging him that absolutely want him dead, it isn't much of a surprise.

Also, did anything of cultural significance in the city got destroyed?

In Seleucus' defence, I wouldn't call him a trash king. I mean it was Antiochus II who created the factional divide which plagued his son's reign (and elevated Ariobarzanes to power), it was Demetrius who first started handing power to local authorities in the east. Seleucus' biggest fault is that he just didn't fix the problems and allowed them to run away. As for Seleukeia, it's not Diomedes burning the city but Aristarchus and only as a side effect of the siege. I'll go into more detail about this later in the story but unfortunately cities getting burned is often a result of armies taking them, even really important cities (remember Persepolis?), it's very easy for an army to just burn it all to the ground.

As for things of cultural significance? Well a lot of art will have been lost, as well as Seleucus' library in the city, the old (pre-Seleucus III) palace etc. Again, we'll go more into detail on the siege of Seleukeia in the next few updates, really I just wanted to tease what's coming for everyone. If anybody caught the epithet of Seleucus IV (Epimanes), they'll know that we're in for some wild times. Thanks all for reading and for feedback!

As for things of cultural significance? Well a lot of art will have been lost, as well as Seleucus' library in the city, the old (pre-Seleucus III) palace etc. Again, we'll go more into detail on the siege of Seleukeia in the next few updates, really I just wanted to tease what's coming for everyone. If anybody caught the epithet of Seleucus IV (Epimanes), they'll know that we're in for some wild times. Thanks all for reading and for feedback!

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Two: Antiochus III and Seleucus IV

Important People:

Diomedes: Regent of the Seleucid Empire (until 205) and 'Hand of the King' (from 205)

Antiochus III: King of the Seleucid Empire

Seleucus IV: King of the Seleucid Empire

Aristarchus: Head of the royal guard and close ally of Diomedes

Alexander: Son of Diomedes and satrap of Syria (after 200)

Andromachus: Son of Diomedes (after 200)

The ascent of Diomedes to the regency in 210 BCE marked the systematic downfall of Amestris and her Perso-Babylonian faction in court politics for the next 24 years, a period during which Diomedes would come to form the political backbone of the Seleucid empire. Now in his defence, Diomedes initially seems to have planned to actually turn power back over to Antiochus III from the outset. In one of the many letters attributed to Diomedes, written in the mid-200s, he lamented his position as permanent regent, claiming that it would have been better had he stepped back when he intended to. This may well be just political pandering by an increasingly unpopular regent as he attempted to justify his hold on power as being simply for the good of the kingdom (that is to say, pretending that he didn't want to be regent forever, he just had to... oh no). However, several others letters by Diomedes repeat this same concept, suggesting that he came to resent the very power he held or, at least, the sheer obviousness of it. See, there is no doubt that Diomedes intended to maintain control over the empire and he had no intention of giving up the control he held but his biggest issue seems to have been the fact that, as regent, he couldn't operate behind the scenes any longer and was forced to out himself as the real power behind the throne. As we will come to see, this would pose several major issues for the regent over the course of his reign.

Born in 221 BCE, Antiochus III was 11 at the time of his ascent to the throne and, most likely, was intended to take the throne in his own right around the age of 14. I say 'was intended to' because Antiochus would remain on the throne for only a year and a half before dying in 208 at the age of only 13. The death itself was not actually particularly suspicious; Antiochus was recorded as having had several bouts of illness throughout his childhood and youth and was often prone to taking to his bed for weeks or months on end. Nevertheless, the timing of his death was enough to raise concerns about what exactly had happened. In the Seleucid court, suspicion very quickly fell upon Diomedes who was accused by some of having had the young king poisoned. In truth, he almost certainly didn't; Diomedes is recorded as having had a good relationship with Antiochus and had actually spent much of the intervening period working to smooth the path to the king's accession to the throne in his own right. In particular, Diomedes had arranged for Antiochus to tour much of the empire and had even organised educational visits to a variety of local officials to teach the king about how his empire actually ran. All this made perfect sense for a man who had risen to power through these very positions and knew the importance of understanding the workings and mechanisms of the empire.

Of course, Diomedes had also taken the time to assert his own control over the government. As regent, one of Diomedes' first acts was to appoint a brand new 'queen's guard' to protect Amestris (now the queen dowager. These soldiers, chosen and appointed by Diomedes himself, acted as a de facto house arrest for the queen, limiting her movements and largely confining her to her chambers for months on end. In addition, her meetings with Antiochus were increasingly limited to the point that, by the time of his death in 208, he almost never saw his mother whatsoever. By the end of 209 BCE, Amestris had even stopped travelling with the court and remained almost constantly in Seleukeia, finally divesting her of the remains of her political power. Several of her supporters were removed from power and Diomedes' own allies put in their stead. What really cemented his grip on control, however, was the effective movement of the Seleucid power-base from Mesopotamia to Syria. As we said previously, this was an ongoing trend regardless of what Diomedes had done but his move towards Syria was based on his own political position since that was his own power base. Over the course of his regency, Diomedes and the court would come to spend more and more time in Antioch and make fewer and fewer trips to Seleukeia. Indeed, they began to make fewer and fewer trips to the eastern half of the empire altogether.

Diomedes seems to have cared little for affairs in Central Asia or Afghanistan and largely appears to have seen both regions as little more than a collection of mountains and deserts inhabited mostly by barbarians and dotted here and there by the odd Greek city. In one letter, penned in the 190s, Diomedes described Sogdiana as:

'So barbarous that even the Greeks are corrupt. They deck themselves in finery and gold and care little for the gods whose temples they would rather desecrate for their own glory than raise them high with offerings... they care more for silk and incense than for virtue and diligence and their soldiers are so weakened by luxury that they resemble the hordes of Xerxes more than the armies of Seleucus and Antiochus'.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Diomedes did little to change the ongoing trend of political power moving more and more into the hands of local officials in the eastern regions of the empire. This began in 208 BCE when renewed raids in the east led Diomedes to agree to allow local powerholders to increase their defence forces and to construct, and maintain, their own fortifications outside of the Seleucid army's control. Now, before we assume that this all came down to Diomedes' own disregard for the region, we should acknowledge that there was more to his decision than just his own prejudices. The death of Antiochus III threw the court into a period of chaos. The heir was not a really a problem; Seleucus IV was soon crowned as king and the regency renewed until he would come of age in 205 BCE. However, the concerns that Diomedes had had Antiochus III murdered had begun to percolate through the court and there were several calls for Diomedes to step down. Okay, this all seems okay, right? After all, Diomedes didn't even want to be regent so why not take the opportunity to step back? Well there are several problems here. First was the fact that Diomedes didn't want to lose his power and stepping down now, and under these circumstances, would almost certainly lead to his political downfall; nobody, after all, was going to keep a potential regicide close to the throne. Secondly, there was the risk that he would simply be arrested should he step down. Even if he didn't kill Antiochus, there was no telling what the next regent would think or do. Even if said regent didn't think Diomedes had committed any crime whatsoever, he might simply have the former regent arrested and executed to shut people up or to prevent a counter-coup against his power.

This is all to say that Diomedes could not have simply stepped down yet. The best, and only, time would have been in 205 BCE when Seleucus took the throne and Diomedes could simply retreat to some sort-of high position within the court and keep the king on a tight leash while avoiding the spotlight of the regency. That was probably his plan with Antiochus prior to the king's untimely death, after all. So when, in 208 BCE, the local governors east of the Zagros mountains came asking for either a Seleucid military intervention to put down raids and protect their cities or for the right to increase their own power, Diomedes chose the latter. Doing so would not only potentially create allies in the east, but prevent him from having to order a costly and difficult military campaign at a time when his own power was relatively weak. He wouldn't abandon the east entirely, however, and in 206 BCE he would send a force to the east under the command of general Aristarchus to respond to requests for help but for the most part, the divestment of more military power to local actors seemed to work and with their increased armies they were able to protect their regions and put down raids and revolts.

The next problem became very apparent very quickly. See, with Seleucus IV on the throne, all focus now lay on the young king. As he had done with Antiochus, Diomedes began a very systematic education programme for the new king; touring the empire, introducing him to his subjects and government, visiting Macedonia etc. Seleucus, however, showed very little interest in any of this. In fact, he showed an entire lack of talent for any business of government whatsoever and an absolute disdain for the people who ran his empire. The impression we get through the sources is that Seleucus was not especially bright nor charismatic and cared little for the empire he had inherited beyond the luxury and wealth it afforded him. One history, admittedly written much later, sums it up by quoting Seleucus as having said:

'The kingdom is but a farm and the people are but pigs and cattle- they exist only to provide food and wealth'

Again, the quote itself is certainly invented but it does neatly sum up the impression we get of Seleucus through our sources. Indeed, the most distinguishing thing about Seleucus from this point in his life is his very worrying love of animals. That is to say, his love of torturing and killing animals. We are told a whole litany of crimes committed against all sorts of animals by the young king but, for the sake of the reader and myself, I shall not detail them here. That said, king Seleucus IV quickly began to worry his courtiers and, not least, Diomedes himself. Not only was the king unsuitable for rule but his cruelty seemed only to grow by the day. Still, he was the king and right up until his coming of age in 205 BCE, the court seems to have held out hope that he might turn things around. Given that history remembers Seleucus IV as 'Seleucus Epimanes' or Seleucus 'the mad', I'm sure that savvy readers will be able to tell where this is going.

With that said, it was not Seleucus' psychotic tendencies that convinced Diomedes not to relinquish power, at least not by themselves. In truth, it was the increasingly strained relationship between the king and his regent. Convinced of his own power and rights as king, Seleucus cared little for Diomedes or for his guidance or education and his active rejection of Diomedes' instruction began to worry the regent. See, Diomedes' refusal to step down had begun to fracture his once-strong support base. Several of his own supporters had begun to eye up his position and the rumours of Diomedes' murder of the former king were only growing stronger as he refused to address them. Fearing that Seleucus would be predisposed towards removing him from power (and possibly his head from his body), Diomedes began plotting to prevent his opponents from accessing the king whatsoever. Throughout 206 and early 205, Diomedes increasingly sequestered Seleucus, keeping him quiet with a steady supply of animal victims to torture and kill while he tried to work out exactly what to do about his position. His solution was as heavy handed as it was effective; he simply brought the army in. In March 205, only a few weeks before Seleucus' birthday, Diomedes had several members of the court arrested on, probably forged, accounts of treason and, on this basis, ordered the royal guard to be increased. Under the command of Aristarchus, the royal guard grew dramatically, granting Diomedes complete control over the court once again.

A few days later, the 'king' (that is, Diomedes issuing decrees in Seleucus' name), issued a new series of regulations on court protocol. Now, all business with the king was to be conducted only through the person of the new 'Hand of the King', a position which had no real defined powers but, under Diomedes, effectively amounted to controlling anything and everything he wanted. In name, the 'Hand of the King' was something close to a high chancellor or chief minister of the Seleucid empire and would act as a liaison between the king and the court. In truth, the 'Hand of the King' now controlled all business of the court and any and all access to royal power. With this, Diomedes formally relinquished the regency in April 205 BCE and Seleucus, officially, ascended to the throne in his own right. Of course, if anybody wanted to actually see the new king, they would have to go through Diomedes. Even at official events such as symposia or meetings, Seleucus was often absent or sequestered away from the court itself, often behind a curtain. Convincing Seleucus to go along with this was not especially difficult and Diomedes continued to feed him the idea that he was simply too good to have to deal with all these petty aristocrats. What had started out as an attempt to protect himself had now very quickly spiralled; Diomedes' presence as regent, the rumours of regicide and his increasingly heavy-handed approach to rule was making more and more enemies in the court and left him with fewer and fewer friends.

In this, Aristarchus grew ever more powerful as well, heading up the royal guard and acting as Diomedes' right-hand man. In 204, he was married to Diomedes' 20-year-old daughter Demetria. In the same year, Diomedes' two sons, Alexander and Andromachus, were raised to captaincy positions within the royal guard from which they would quickly move to other high positions. By 200, Alexander was satrap of Syria while Andromachus was satrap of Mesopotamia. Between them, the two would wield an immense amount of power over both the financial and political power of their regions. Indeed, over the early 190s, the positions of satrap and dioiketes within both Mesopotamia and Syria were simply fused under the commands of Alexander and Andromachus so as to consolidate more and more power in their hands. The final nail in the coffin for Diomedes' opponents came in 199 BCE when Amestris 'committed suicide' after years of increasingly strict house arrest. With the death of the queen dowager, Diomedes finally felt secure in his control of the throne and now turned his attention to reshaping the empire in his own image. One of Diomedes' major concerns was the collection of revenue, an issue that he had come to have very passionate thoughts about.

Estimates are difficult but the population of the Seleucid empire between 281 and 190 BCE is estimated at somewhere between 20 and 25 million people, a bit lower than Alexander's empire at its height (about 25-30 million). By the middle of the 3rd Century, the population of Mesopotamia was probably about 4-5 million and the population of Northern Syria about 1.5 million but by the time of Antiochus III, these may well have risen to about 6-7 million in Mesopotamia and 2-2.5 million in Northern Syria. Over time the population of Syria would increase to the point at which the total population of Syria (northern and Coele Syria combined) has been estimated at about 6 million in the mid-2nd Century under Argeus I. Revenue is also difficult and varies a lot over the entire empire but one scholar estimates an average of about 1.5 talents per thousand people in the Mediterranean region, 1.25 per thousand in Mesopotamia and 0.5 per thousand in the Upper Satrapies east of the Zagros mountains. This would mean that, if these numbers are true, Syria alone provided about 9000 talents in revenue every year from taxes alone. That is, of course, not taking into account issues such as tolls and trade as well as mitigating issues such as tax exemptions, declines in income, environmental issues reducing tax, crime etc. This is all to say that estimating the actual wealth of the empire is exceptionally difficult. That said, one estimate places the income of the empire around 230 BCE at around 19-20,000 talents per year in taxes before the Great Syrian war. Estimates are even dodgier afterwards however but one scholar has suggested that the impact of the war may have reduced income to about 14-15,000 when he account both for the devastation in Syria as well as population loss in Mespotamia, the impact of the court's prolonged stay in the region and the increasing chaos in the Upper Satrapies.

(For context, a talent was about 36,000 obols. An average daily wage for a labourer in Classical Athens would be about 2 obols a day. To put this in context, then, 19-20,000 talents equated to between 684 and 720 million obols a year).

Antiochus' military campaigns had also been very expensive. His ship building, massive building projects, constant adventurism and endless wars with the Ptolemies had cost vast sums of money over the course of his long reign. Forts had to be maintained, crews paid, soldiers paid, food bought, horses maintained, buildings constructed, roads constructed, the court maintained and many other expenses. In peace, one estimate places the 'peacetime' expenditure of the Seleucid army at around 7-8000 talents per year and some 2-3000 talents for the running of the administration. That equates to around 9-11,000 talents per year while at peace. So at the height of revenues under Antiochus II all seemed well; a total surplus of 9-11,000 talents per year. However, between the constant expenditure of wartime activities had also taken their toll, especially during the latter half of his reign. Over the course of the great Syrian war, revenues had plummeted while costs skyrocketed and these revenues had never really picked up again.

Diomedes' focus, then, was to try and increase the revenue of the empire by any means necessary and decrease its expenditure. To this end, he began to roll out more and more local prerogatives for localised military control, granting increased rights to local communities and even satraps to maintain certain forts at their own expense. Major forts would remain under central control, but some local sites would either be mothballed or handed over to local authorities to staff with militias and defence forces. In mid-190s, Diomedes also experiments with grouping satrapies together and granting these new groups the right to raise joint armies and defence forces to protect their own interests. These local defence forces would become more and more common over the 190s and early 180s and existed in one form or another, especially in the Upper Satrapies and Macedonia well into the reign of Argeus I and his successors.

In the short term, they did manage to reduce the expenditure of the empire but they also risked destabilising it, increasing the risk of local powerholders creating their own bases and coming to resent centralised control. It would be a problem that the later Seleucid kings would struggle against for much of the 2nd Century and one that Diomedes would come to know well before the end. In addition to this, he increased the taxes on landholders with particularly large estates and attempted to introduce a more formalised system of tribute collection. In particular, he attempted to move the collection of taxes away from the satraps themselves and towards the dioiketes beginning around 199 or 198 although this wouldn't go very far since a series of major protests would put a halt to it soon enough. In 196 BCE, increased tribute demands in Ionia led to a major revolt and the deployment of the army under Aristarchus to put it down. More problematically, Diomedes made a very radical attempt in the 190s to establish a single capital at Antioch, effectively attempting to end the process of mobile kingship in the Seleucid empire and centre it upon a single city in the vein of Alexandria. This would end in disaster as the costs of maintaining the court (and armed forces) indefinitely began to exhaust the population of northern Syria and led to a serious revolt in 194 BCE.

In addition, the ever increased costs of making the trip to Antioch for satraps further from the court began to reduce these trips over time. One of the more difficult decrees was issues in 197 BCE, shortly after the settlement of the court at Antioch. Under this, every satrap was required to visit Antioch for at least three weeks every year in the case of satrapies between Macedonia and Mesopotamia or ever two years in the case of those beyond the Zagros mountains. As a power move it made some sense; by forcing satraps to come to the capital, Diomedes was forcing them to spend money and take time away from their power bases in a location where they would effectively be hostages of the crown (that is to say, Diomedes). In theory, it would also reduce the expenditure of the throne which no longer had to travel to the satraps to engage with them. Of course, this went down like a lead balloon; worsening conditions along the roads, especially in the Upper Satrapies, made it more expensive, dangerous, and difficult for satraps to make the trip to Antioch and the constant demands for increased revenue and travel began to grate upon them more and more. In an ever-worsening political situation in Central Asia, it soon became ever more common for satraps to outright rebel against the throne as they failed to actually make the trip (or refused to do so for political reasons). We'll discuss this situation more next time but, for now, it suffices to say that all of this went down pretty badly.

Simultaneously, Diomedes was empowering and trying to neuter local political actors across the entire empire and it was not very popular. At court, his decisions rightly drew criticism of effectively undermining the Seleucid empire at its very base while, out in the satrapies, it drew criticism for increased surveillance of satraps and the attempt to steal their ability to collect taxes as well as the ever increased demands placed upon satraps to travel to Antioch and bring more income. For a man whose career had been built on his financial ability, it all seems rather strange. However, Diomedes seems to have been attempting to create a more bureaucratised system. In his mind, the Seleucid empire (which was already very bureaucratic, let us not deny that) was something which needed to be reformed into a system of appointments and highly regulated satrapies. Sure, he was empowering the satrapies but, in theory, he was taking other powers away to strengthen other arms of the bureaucracy in turn. Despite the increasing divestment of power to the provinces, Diomedes appears to have seen this was being a centralisation programme, one which would break local powerholders, end any local dynasts and, eventually, create a uniform bureaucracy across the whole of the empire in which satraps simply governed and fought conflicts at the local level and the dioiketes collected taxes. In this system, satraps would ultimately be subject to the king's oversight upon their 'reports' back in Antioch and all the central authorities would have to do is keep order and march out whenever the satraps faced a problem they couldn't handle. If that was the case, of course, these reforms simply didn't work.

--------------------

Note: For sources on the revenue and expenditures of the Seleucid Empire, check out Aperghis (2004), 'The Seleucid Royal Economy'. Many of the numbers come from Aperghis himself with some jumbling for my own timeline but they are very heavily estimated and there really is no way of truly knowing. Population and revenue are notoriously difficult as are the questions of what these numbers actually mean. We know, for instance, that daily wage in Classical Athens was about an obol or two but how that translates to modern money is not only controversial but often a meaningless discussion.

Important People:

Diomedes: Regent of the Seleucid Empire (until 205) and 'Hand of the King' (from 205)

Antiochus III: King of the Seleucid Empire

Seleucus IV: King of the Seleucid Empire

Aristarchus: Head of the royal guard and close ally of Diomedes

Alexander: Son of Diomedes and satrap of Syria (after 200)

Andromachus: Son of Diomedes (after 200)

The ascent of Diomedes to the regency in 210 BCE marked the systematic downfall of Amestris and her Perso-Babylonian faction in court politics for the next 24 years, a period during which Diomedes would come to form the political backbone of the Seleucid empire. Now in his defence, Diomedes initially seems to have planned to actually turn power back over to Antiochus III from the outset. In one of the many letters attributed to Diomedes, written in the mid-200s, he lamented his position as permanent regent, claiming that it would have been better had he stepped back when he intended to. This may well be just political pandering by an increasingly unpopular regent as he attempted to justify his hold on power as being simply for the good of the kingdom (that is to say, pretending that he didn't want to be regent forever, he just had to... oh no). However, several others letters by Diomedes repeat this same concept, suggesting that he came to resent the very power he held or, at least, the sheer obviousness of it. See, there is no doubt that Diomedes intended to maintain control over the empire and he had no intention of giving up the control he held but his biggest issue seems to have been the fact that, as regent, he couldn't operate behind the scenes any longer and was forced to out himself as the real power behind the throne. As we will come to see, this would pose several major issues for the regent over the course of his reign.