They were lucky a few times, and had some very bloody victories. After that they were just pushing into enemies that were already collapsing.So the Spanish just bowled over everyone in their path with no real defeats?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Undying Empire: A Trebizond Timeline

- Thread starter Eparkhos

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 96 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part LXXIV: Dueling Patriarchs (1545-1547) Appendix: The Apocalypse of David Part LXXV: The White Horse (1551-1553) Part LXXVI: The Invasion of Syria (1553-1554) Part LXXVII: Armageddon (1554-1555) Appendix: al-Sirozi Part LXXVIII: Long Live the Aftokrator? (1556-1559) On the Future of the Timeline

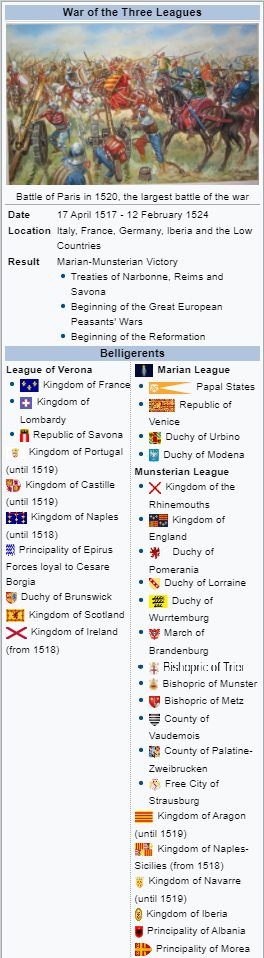

War of the Three Leagues wikibox

Eparkhos

Banned

Alright, if you're not willing to read the whole section on the Three Leagues (I don't blame you), here's a wikibox for it:

So we've learned in passing that Epirus has been conquered (but not by whom). Also, the wikibox mentions that the War of the Three Leagues somehow leads to the Reformation. Very interesting. I wonder if the proto-Protestant Savanarolla & his crew have something to do with this TL's Reformation.

I feel that France will see significant losses, but an issue with carving the place up wholesale is its impacts on the balance of power in Europe, which while not as dominating an issue as during the 18th century onward, is still going to weigh heavy in the minds of rulers in Italy, Germany, Britain, et cetera. For example, it's in the interests of both Lusitania/Iberia/Hispania and the Holy Roman Empire to limit the gains of one another lest they come to encroach on ambitions in Italy, as is the case with Iberia and England due to their status as rival maritime trade nations. The most natural way to do this is to keep France from being dismembered, and keep it as a potential counterweight against anyone getting too big for their britches. England, for example, can/will probably expand the Pale of Calais, and if succession is messy enough might be able to back a pretender to the French throne, but restitution of control over Normandy is incredibly unlikely (though that's in part due to their mediocre performance in the war, unlike Iberia or the Dutch/Rhinemouthers).At first, I thought people were being a bit silly with their hopes of an independent Burgundy being resurrected, etc.

Now I'm half-convinced that France is getting carved up like a turkey and getting left as a rump state is a best-case scenario. Between the Spanish overruling the entirety of the south, the English in the north, and the Germans/Lowlandsers at the gates of Paris, plus a universally loathed king that's now dead and probably left behind a messy succession, the biggest question I'm left with is wondering who's even in a position to sue for peace on behalf of the French and what's going to force the respective occupiers out if at all.

Would not be surprised if Morea annexed it, given Palaiologan claims to Epirus as former Byzantine territory.So we've learned in passing that Epirus has been conquered (but not by whom). Also, the wikibox mentions that the War of the Three Leagues somehow leads to the Reformation. Very interesting. I wonder if the proto-Protestant Savanarolla & his crew have something to do with this TL's Reformation.

Damn France got absolutely destroyed. Wouldnt be surprised if the France that does come out will be severely weakened and potentially even be a rump state.

I believe that past a certain point, any further conquests by the Three Leagues will be unsustainable.

Expanding past the Pyrrenean principalities for Spain, past the Alps for the Italians and past the Somme (although I'd argue even Picardy and Boulogne is too far) for the Rhinemouthers.

France is still a very heavily populated area which reunited in the flames of the Hundred Years War. It will be coming back, and the best way to ensure it does not isn't crippling it but, a contrario, not sticking your neck out.

Expanding past the Pyrrenean principalities for Spain, past the Alps for the Italians and past the Somme (although I'd argue even Picardy and Boulogne is too far) for the Rhinemouthers.

France is still a very heavily populated area which reunited in the flames of the Hundred Years War. It will be coming back, and the best way to ensure it does not isn't crippling it but, a contrario, not sticking your neck out.

Very apreciatedAlright, if you're not willing to read the whole section on the Three Leagues (I don't blame you), here's a wikibox for it:

Clearly they'll suffer from Pttoman poisoning.Even if the Pttomans royally screw up the war at sea, what prevents them from rolling over the Trebizond's frankly terrible army?

Wouldn't word be coming from the west, not the east?But then, word came from the east. An army of crusaders had invaded Rumelia, and the Italians had also declared war against the Sublime Porte,

I believe that past a certain point, any further conquests by the Three Leagues will be unsustainable.

Expanding past the Pyrrenean principalities for Spain, past the Alps for the Italians and past the Somme (although I'd argue even Picardy and Boulogne is too far) for the Rhinemouthers.

France is still a very heavily populated area which reunited in the flames of the Hundred Years War. It will be coming back, and the best way to ensure it does not isn't crippling it but, a contrario, not sticking your neck out.

This is pre-nationalism, carving up a kingdom is by no means off the table. Especially when some like the English think they have a claim to the lands themselves as kings, or the Spanish who almost recreated Ceasar's romp through Gaul. Doubly so when the region is far from linguistically unified. Carving off the entire south and Brittany forever isn't out of the realms of possibility here. Throw in cultural assimilation, emphasizing linguistic differences, etc. and you can absolutely crush France's hexagon and turn it into an oversized Ile-De-France even if the invading powers are kicked out with regionalism keeping the place split into statelets, a north-south split, etc.

Actually, it is not pre-nationalism for France and England, because the Hundred Years War was the formative experience for French and English nationalism.This is pre-nationalism, carving up a kingdom is by no means off the table. Especially when some like the English think they have a claim to the lands themselves as kings, or the Spanish who almost recreated Ceasar's romp through Gaul. Doubly so when the region is far from linguistically unified. Carving off the entire south and Brittany forever isn't out of the realms of possibility here. Throw in cultural assimilation, emphasizing linguistic differences, etc. and you can absolutely crush France's hexagon and turn it into an oversized Ile-De-France even if the invading powers are kicked out with regionalism keeping the place split into statelets, a north-south split, etc.

Actually, it is not pre-nationalism for France and England, because the Hundred Years War was the formative experience for French and English nationalism.

Being the thing people point back to and say this is where people started to identify with a nation is way, way different than nationalism taking root. Almost any society experiences tribalism, who belongs and who doesn't and it way predates either England or France. It's only significant here in retrospect because these states happened to last into the modern-day so we can point back and say 'Here is where it started'. How many other group identities have been forged only to die out?

What is Joan of Arc if not nationalism ?Being the thing people point back to and say this is where people started to identify with a nation is way, way different than nationalism taking root. Almost any society experiences tribalism, who belongs and who doesn't and it way predates either England or France. It's only significant here in retrospect because these states happened to last into the modern-day so we can point back and say 'Here is where it started'. How many other group identities have been forged only to die out?

Santa to the rescue!!!One of the galleys, the Agios Nikolaos, rammed a commandeered fishing vessel and sliced cleanly through it to ram a merchantman

There is functionally very little information on this area, which always surprised me. However, I can easily see @Eparkhos simply acting like Trebizond already has its own independent Patriarch.

Eeee....Basileios Funa was determined to attain the title that he considered rightfully his and his successors’; the Patriarch of Trapezous

Not sure this is viable.

Historically, Patriarchs/patriarchies were directly associated with the lives and ministries of the early Apostles. Even Constantinople had to fudge the situation, and get the bones of St. Andrew moved there to be able to set up a patriarchate there.

While it's true that the Serbs claimed a Patriarchate from 1346, without any apostolic basis, that is the very first, afaik. IOTL, Moscow didn't become a Patriarchate until 1581, so this is a VERY significant moving forward of things.

I would have thought that the Pontic metropolitan would simply have denied the validity of the Ecumenical Patriarch, possibly claiming the title for himself. But trying to set up a new Patriarchate? In Greek lands? Seems really, really unlikely to me.

Edit: hunh. Apparently the Georgians have had a Patriarchate since 1010, although they do have/claim an apostolic connexion - multiple, in fact.

Still, Georgia was ethnically and linguistically distinct.

See aboveThe Russian Church. In 1461, the Metropolitan of all Russia, St. Jonah, unilaterally declared himself Patriarch of Russia, and was excommunicated by the Ecumenical Patriarch because of it. Now his successor, Philippos, maintained his claim, and was willing to make common cause with Basileios to advance their joint claims. Basileios agreed, and in 1471 the two would-be patriarchs declared that they would not accept communion with the Patriarch of Constantinople unless they were both elevated.

???? Dionysus the Areopagite was the first bishop of Athens, supposedly appointed by Paul himself. There's also, of course, St. Dionysus of Paris, who (as St Denis) has been patron saint of France for a while now.However, this changed in 1467, with the ascension of Dionysios to the Patriarchal throne. His very name--why on earth would he think that taking the name of the Demon of Debauchery[3] was a good idea?--angered Basileios,

Last edited:

Idk it just doesn't feel realistic for things to go so smoothly for Portugal/castille, no domestic issues due to the union of the two states thus hampering any war effort? No battles lost against the Aragonese? No outcry from the rest of Europe that the king invaded Aragon with a sketchy casus belli at best and just declared it his? Really?They were lucky a few times, and had some very bloody victories. After that they were just pushing into enemies that were already collapsing.

All imo of course, OP's story and they can do what they like

Je serai votre champion.

Part XLIII: Peace? (1523--)

Eparkhos

Banned

And now, I present to you the final installment of the saga of the Three Leagues, to be accompanied tomorrow by a map....

Part XLIII: Peace? (1523--)

The end of the Middle Ages is most commonly dated to either 1453, with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire[1], or 1523, with the death of Louis XII in battle and the resulting end of the War of the Three Leagues. The selection of the latter date is quite rational, as the War of the Three Leagues did mark a turning point in European history. Many of the war’s aftershocks--the Second Jacquerie, the Bauernkrieg, and the Great Saxon Rising--were inevitable before the war was even over, as the great losses in men and material that had been caused by the half-decade of war made increasing taxes on the already desperate peasantry a certainty. The sheer amount of death and destruction during and because of the war was by itself enough to close this chapter of history, but the longest-lasting effects of it would come with the treaties that ended it.

The House of Valois had a problem with male heirs, namely that there were very few. Through a string of diseases, unfortunate accidents and all-around bad luck, the once sprawling family tree had parsed down into a glorified shrub. For the first few years of his reign, Louis’ heir-apparent had been his cousin, Louis de Valois-Orleans[2], but his death in 1515 had shunted the title of crown prince off to his even more distant cousin, François d'Angoulême[3] who was in his early twenties and was married to Claude of Brittany, the scion of a family known for its fecundity. Surely, the succession was safe. But then Francois fell in battle against the Marians in 1520, and Claude miscarried a posthumous son, ending the male line of yet another Capetian cadet branch. This sparked a succession crisis, as the next eligible claimant to the throne was none other than Philip II of the Rhinemouths. Even as the war raged on in the north, there was a distinct possibility that it might all be ended by Philip inheriting the French throne. This period only lasted a year, however, and in 1521 Louis declared that no member of the House of Burgundy would be allowed to sit upon the French throne under any circumstances, and this was backed up by the hastily-assembled Estates General. With Philip disinherited, the position of next-in-line effectively became empty, while the next-in-line was tracked down. The House of Valois-Bourbon was essentially extinct in the male line, their only surviving legitimate man being Louis, the Bishop of Liege, who was rapidly approaching his eightieth birthday. The Bourbons had been the most fecund of the Valois cadet branches, but every other male member of the clan had fallen in battle during the war, a show of shocking misfortune. At long last, the archivists and genealogists managed to track down the closest surviving male relative of the Valois (other than Louis, of course); his tenth cousin twice removed, Charles d’Alençon. Charles was well-liked and had proven himself in battle against the Iberians, and so he was an excellent pick for heir-apparent. There was the slight problem that his wife was barren, but that could be worked out when they weren’t at war with the pope.

In February 1523, after Louis was finally killed in battle, Charles IX was swept onto the throne. Not clouded with pride and delusion like his cousin had been, the new king recognized that the war had been as good as lost since 1521. He sued for peace at once, hoping to end the foreign conflicts so he could turn his attention to dealing with the murderous, thieving hordes of militant peasants who were running around Poitou and Normandy. The Munsterians had similar problems of their own, the Bauernkrieg having begun in full force, and they were already on the verge of exhausting their collective funds. As such, they were agreeable to a peace conference. The Marians, meanwhile, were having a field day on the Lombard plains, and they stalled a ceasefire until they had managed to recover everything except Milan, so they had as strong a negotiational position as they possibly could. However, by the end of June 1523, all parties had agreed to a peace settlement, to be conducted in three different conferences (per se).

The first treaty was conducted between France and the Iberian states, in the Peace of Narbonne. Duarte was more or less satisfied with the bulk of his possessions on the southern side of the Pyrenees, but saw expansion northwards as an opportunity to create a valuable buffer zone between France and the lands he actually cared about. The Count of Rodez had also pledged his fealty, and the king felt pressured to protect him lest he appear unreliable and borderline traitorous to the rest of his vassals. Charles, for his part, just wanted a stable and neutral southern frontier so he could concentrate on internal affairs and not have to worry about raiders from the south further exacerbating problems. After a few days of negotiations, they came to an arrangement. The Viscounties of Bearn and Begore had previously been vassals of the Navarese crown, and so Charles ceded them to Duarte in his role as King of Navarre. The counties of Foix and Commiges would also be given over to Aragon, as well as Toulouse and the lands immediately surrounding it. Rodez would also be ceded to Aragon, but would remain as an exclave from the kingdom proper. No financial penalties would be imposed upon either party. This peace was agreeable to both monarchs, but it angered the French nobles, and Charles was nearly assassinated upon returning to Paris.

The next peace was concluded with the Munsterians. Edward had effectively pulled out of the conflict and was desperately trying to put down the Geraldine Rising in Ireland, which had succeeded in driving the English out of the island bar only Dublin and Cork, which were under siege as the diplomats spoke. The Rhinemouthers were on the verge of financial insolvency, having borrowed great sums of money from domestic bankers to support the war effort, and had suffered much damage from de Foix’s raids. The Munsterian states were also badly battered by their losses from the war and especially from the Great Raid of 1521, and Eric was only able to keep them working together with the promise of imminent victory. Bogislaw, meanwhile, had pulled back from the war as well, having to deal with the Bauernkrieg, which was the mother of all peasant revolts and was currently savagining Swabia and Thuringia. There was also the Lower Saxon Rising, which had been sparked by the French-aligned Duke of Brunswick fleeing from Imperial armies into Saxony, burning and looting as he went, which had driven the peasants to throw out their rightful rulers and establish independent republics and militia councils with the goal of local self-defence. This was intolerable to the feudal lords, and many of the princes of the Empire were threatening to elect an anti-emperor who would do something about the rebels if Bogislaw didn’t help them.

My point is, the Munsterians were on the verge of breaking themselves, and so they were hardly in a position to impose crushing terms against the French. Because of this, the changes in territory at the end of the war was surprisingly small. The Rhinemouthers would annex Picardy, which they had briefly held in a dynastic union twenty years beforehand, and Guise to the Rhinemouths proper, while the County of Rethel would be subject to the Duchy of Luxembourg, which was in personal union under Philip II. South-eastern Champagne would be annexed into the Duchy of Lorraine, while the Duchy of Bar would be broken off and given over to Bogislaw’s youngest son, Barnim[4]. There were also a number of fairly minor border arrangements, with several Munsterian states annexing a few castles or towns along the border. The Duchy of Brittany would also have its independence restored to it, with the complex chain of marriages and suspicious deaths that had once nearly brought it into personal union with France wound up placing Pedro de Navarre, former regent of Navarre, upon the Breton throne. Finally, an incredible amount of money would be paid to the Munsterians, equivalent to the total income of the French crown for a year, to be distributed amongst the states of the League ‘for the benefit of all’. Most of this money was taken by Philip to pay back his money-lenders, but enough made it to the smaller states to allow them to at least start paying down their debts. Such a large indemnity severely weakened the strength of both France at large and Charles himself, and the increased taxes needed to make up the balance and keep the state running merely exacerbated the ongoing peasant uprisings across France.

And, finally, there was the Treaty of Savona, conducted between France and the Marians in early 1524 after several months of tenuous negotiations. The Marians were doubtlessly victorious in the region, having effectively driven the French and their allies from the peninsula almost entirely on their own. Because of this, they were rather arrogant and, despite Hyginus’ best attempts at diplomacy, it was nearly impossible to establish internal agreement, which made presenting a united front towards the French, to say the least. At long last, the Pope was able to wrangle his supporters and met with Charles personally at Savona in August 1523.

Savona and Lombardy, as steadfast allies of the French, would be shown little mercy. Savona’s mainland territory would be halved, with Genoa being reclaimed by the Calvians[5] and everything east of Rapallo being annexed by Tuscany. However, they would be allowed to rebuild their fleet to as great extent as they pleased, and they kept most of their trading posts in the western Mediterranean, albeit because of logistical problems in transferring them to Calvi or Venice rather than any legitimate mercy. Hyginus would recognize Giovanni Comnini, who was elected as doge in 1525, as legitimate Lord of Savona a few weeks later, and the Savonese would join the Trinitarian Coalition against the barbaries a few years down the road. Naples would be officially recognized as the possession of the former Ferdinand III of Aragon, and in a later treaty between Duarte, Ferdinand and Hyginus, Sardinia, Sicily and the Balearic Islands would all be recognized as de jure territory of Naples, marking an effective reversal of the dynastic situation of previous centuries.

However, the most dramatic impact of the Treaty of Savona was in northern Italy itself. Lombardy, as both a kingdom and as a state, would be dismembered in its entirety. Venice would regain most of its pre-invasion territory along the Po plain, except for Mantua, which more than doubled its mainland holding with the stroke of a pen. That most of this region was a burned-out wreck of its former self, as was most of northern Italy by this point, does not seem to have bothered the Doge. The island fortress of Ile-du-Roi would be razed and its weapons distributed amongst the Marian states, with all of the Marian states agreeing to prevent the construction of any fortress here in the future, which would prevent the passage of vessels up the river. Modena would expand itself greatly, annexing Parma and Ferrara from Lombardy. By now, the region had been so devastated by the back-and-forth fighting that Ferrara was the only halfway decent city left, and so it became the capital of the newly-established Grand Duchy of the Four Cities. Urbino also gained new territories, being awarded the fortress city of Mantua in what was almost certainly a calculated effort to turn the Urbinians and the Modenese against each other and thus allow Hyginus to wield more influence over them both. The Tuscans would move their border further north, to the northern foothills of the Apennines, securing them a defensible frontier and a great deal of influence over the regions to their north. And, of course, new states were carved out of Lombardy. The Duchy of Savoy was returned to its exiled dynasty, stradling lands in both the lowlands of Italy, the Alps, and the lowlands of Provence. The Duchy of Alessandria was carved out around the city of the same name, its ruler being a friend of Hyginus named Alessandro Agostino Lascaris[6]. The Counties of Piacenza and Cremona were also established, once again around the cities of the same name, and were made the segnorities of Fredrico di Gonzago, the exiled descendant of the former Dukes of Mantua. More importantly as far as Hyginus was concerned, he had been one of his closest political allies in Rome and had helped in the defense of the city against the army of the Borgias. The city of Como, Hyginus’ former residence during his time as a cardinal, was annexed into the Papal States, while Avignon and Benevento were restored to Roman control. Finally, the remnant of the Kingdom of Lombardy was formerly reduced to the Duchy of Milan, and Massimiliano Sforza, the son of the last native duke, was restored to the Milanese throne.

The Duchy of Provence would also be raised to a state in personal union with France, rather than an integral part of it as it had been before. This had little immediate impact, but Hyginus intended for it to complicate the relations between the two states and turn it into a quagmire that would reduce its value as a staging point. No money would change hands, however, as Hyginus sensed the financial weakness of the French monarchy and feared that destabilizing it would only worsen the ongoing crisis, a fear that had far more justification than he knew. Finally, on the far side of the Adriatic, the secondary Epirote theater of the war was also brought to a close at Savona. The Epirotes had been a Neapolitan protectorate before the war, and upon the outbreak of the war they had been attacked by the Venetians and the Venetian-allied Albanians and Moreotes. When the war in Naples had spiraled out into civil war, Epirus too had collapsed into civil war between the French-aligned Carlo III and the Aragonese-aligned Ferrante. Ferrante had triumphed after receiving support from the Venetians, but he was a puppet of the Serene Republic because of it. The Venetians would annex Vonitsa, Preveza and all the islands of the region, while the Albanians would seize everything north of Ottoman-held Sarandoz and the Moreotes would annex Missolonghi and the lands around the Aitoliko lagoon.

While the War of the Three Leagues was over, a time of great strife had only just begun. Central France and much of Germany[7] were consumed by revolts as hungry and angry peasants rose up against their oppressors in hopes of ending centuries of oppression. In the east, Hungary, Austria and Serbia had all been devastated by a long-running civil war between the newly-ascended Ladislaus V and his brother Janos[8], the prosperity of the Raven’s reign wiped away in a few scant years. Across Europe, many thousands lay dead from hunger and hundreds of thousands struggled to survive, their lands and homes wrecked by the shadow of war or raids from neighboring states. With the chief maritime powers of the Mediterranean engaged in a death-struggle, the barbary corsairs had had a field day, ravaging the coasts of the western Mediterranean and enslaving thousands. The common people of Europe were tired, desperate and disillusioned, having watched their sons and brothers march to their deaths for the sake of some petty noblemen. The fires of revolt burned across much of the region, but it was only with the publication of the 67 Articles of Ulrich Zwingli that these fires would rise into an all-consuming inferno….

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] The Hundred Year’s War ended in 1458 ITTL, so there is far less impetus for 1453 to be considered the close of the era. The survival of the Moreotes and Trapezuntines also weakens the argument that it ended the Byzantine Empire, so the Fall of Constantiople, while still significant, isn’t as important.

[2] OTL’s Louis XII

[3] OTL Francis I. I’m using the modern form of his name here, btw, he wrote his name ‘Francoys’.

[4] The succession laws of Pomerania dictated that each son would receive an equal amount of their father’s land unless they were awarded appenages before his death. Bogislaw intended his eldest son, Kasmir/Conrad to succeed him as Duke of Pomerania and Brunswick and Anna as Duke of Brandenburg, and so gave appenages to his other three sons; Georg, his second son, became Duke of Anhalt, and his fourth son, Otto, became Burgrave of Donha.

[5] Genoa was by now so thoroughly wrecked by five subsequent battles during the War of the Three Leagues that it was effectively useless, and Calvi remained the capital of the republic. It is likely that Hyginus advocated this in hopes of further involving Calvi in mainland affairs, so that he could use it as a counterbalance against the Venetians.

[6] Alessandrio is a female-line descendant of Ioannes Vatatzes, but still used the prestigious Lascaris surname because, after all, who was going to stop him? Vatatzes’ ghost?

[7] The Bundschuh Movement occurred as in OTL, but the spark of the Bauernkrieg was not Luther’s writing as in OTL but rather several years of drought and famine that exacerbated the already tyrannical tax systems of the Carinthian lords. Joss Fritz and his peasant army kicked off the Bauernkrieg proper with their sack of Heidelberg in 1519, and since then a mixture of insurgencies and outright revolts have crippled central and southern Germany, with no signs of stopping. The Second Jacquerie began when the self-defense groups that had been organized to drive off the Munsterian raiders in central France were attacked by their own lords, who feared organized peasants more than they did enemy raiders.

[8] They had a civil war off camera, I couldn’t work myself up to actually make an update for a periphery conflict after spending so much time writing and rewriting the sections on the War of the Three Leagues.

Part XLIII: Peace? (1523--)

The end of the Middle Ages is most commonly dated to either 1453, with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire[1], or 1523, with the death of Louis XII in battle and the resulting end of the War of the Three Leagues. The selection of the latter date is quite rational, as the War of the Three Leagues did mark a turning point in European history. Many of the war’s aftershocks--the Second Jacquerie, the Bauernkrieg, and the Great Saxon Rising--were inevitable before the war was even over, as the great losses in men and material that had been caused by the half-decade of war made increasing taxes on the already desperate peasantry a certainty. The sheer amount of death and destruction during and because of the war was by itself enough to close this chapter of history, but the longest-lasting effects of it would come with the treaties that ended it.

The House of Valois had a problem with male heirs, namely that there were very few. Through a string of diseases, unfortunate accidents and all-around bad luck, the once sprawling family tree had parsed down into a glorified shrub. For the first few years of his reign, Louis’ heir-apparent had been his cousin, Louis de Valois-Orleans[2], but his death in 1515 had shunted the title of crown prince off to his even more distant cousin, François d'Angoulême[3] who was in his early twenties and was married to Claude of Brittany, the scion of a family known for its fecundity. Surely, the succession was safe. But then Francois fell in battle against the Marians in 1520, and Claude miscarried a posthumous son, ending the male line of yet another Capetian cadet branch. This sparked a succession crisis, as the next eligible claimant to the throne was none other than Philip II of the Rhinemouths. Even as the war raged on in the north, there was a distinct possibility that it might all be ended by Philip inheriting the French throne. This period only lasted a year, however, and in 1521 Louis declared that no member of the House of Burgundy would be allowed to sit upon the French throne under any circumstances, and this was backed up by the hastily-assembled Estates General. With Philip disinherited, the position of next-in-line effectively became empty, while the next-in-line was tracked down. The House of Valois-Bourbon was essentially extinct in the male line, their only surviving legitimate man being Louis, the Bishop of Liege, who was rapidly approaching his eightieth birthday. The Bourbons had been the most fecund of the Valois cadet branches, but every other male member of the clan had fallen in battle during the war, a show of shocking misfortune. At long last, the archivists and genealogists managed to track down the closest surviving male relative of the Valois (other than Louis, of course); his tenth cousin twice removed, Charles d’Alençon. Charles was well-liked and had proven himself in battle against the Iberians, and so he was an excellent pick for heir-apparent. There was the slight problem that his wife was barren, but that could be worked out when they weren’t at war with the pope.

In February 1523, after Louis was finally killed in battle, Charles IX was swept onto the throne. Not clouded with pride and delusion like his cousin had been, the new king recognized that the war had been as good as lost since 1521. He sued for peace at once, hoping to end the foreign conflicts so he could turn his attention to dealing with the murderous, thieving hordes of militant peasants who were running around Poitou and Normandy. The Munsterians had similar problems of their own, the Bauernkrieg having begun in full force, and they were already on the verge of exhausting their collective funds. As such, they were agreeable to a peace conference. The Marians, meanwhile, were having a field day on the Lombard plains, and they stalled a ceasefire until they had managed to recover everything except Milan, so they had as strong a negotiational position as they possibly could. However, by the end of June 1523, all parties had agreed to a peace settlement, to be conducted in three different conferences (per se).

The first treaty was conducted between France and the Iberian states, in the Peace of Narbonne. Duarte was more or less satisfied with the bulk of his possessions on the southern side of the Pyrenees, but saw expansion northwards as an opportunity to create a valuable buffer zone between France and the lands he actually cared about. The Count of Rodez had also pledged his fealty, and the king felt pressured to protect him lest he appear unreliable and borderline traitorous to the rest of his vassals. Charles, for his part, just wanted a stable and neutral southern frontier so he could concentrate on internal affairs and not have to worry about raiders from the south further exacerbating problems. After a few days of negotiations, they came to an arrangement. The Viscounties of Bearn and Begore had previously been vassals of the Navarese crown, and so Charles ceded them to Duarte in his role as King of Navarre. The counties of Foix and Commiges would also be given over to Aragon, as well as Toulouse and the lands immediately surrounding it. Rodez would also be ceded to Aragon, but would remain as an exclave from the kingdom proper. No financial penalties would be imposed upon either party. This peace was agreeable to both monarchs, but it angered the French nobles, and Charles was nearly assassinated upon returning to Paris.

The next peace was concluded with the Munsterians. Edward had effectively pulled out of the conflict and was desperately trying to put down the Geraldine Rising in Ireland, which had succeeded in driving the English out of the island bar only Dublin and Cork, which were under siege as the diplomats spoke. The Rhinemouthers were on the verge of financial insolvency, having borrowed great sums of money from domestic bankers to support the war effort, and had suffered much damage from de Foix’s raids. The Munsterian states were also badly battered by their losses from the war and especially from the Great Raid of 1521, and Eric was only able to keep them working together with the promise of imminent victory. Bogislaw, meanwhile, had pulled back from the war as well, having to deal with the Bauernkrieg, which was the mother of all peasant revolts and was currently savagining Swabia and Thuringia. There was also the Lower Saxon Rising, which had been sparked by the French-aligned Duke of Brunswick fleeing from Imperial armies into Saxony, burning and looting as he went, which had driven the peasants to throw out their rightful rulers and establish independent republics and militia councils with the goal of local self-defence. This was intolerable to the feudal lords, and many of the princes of the Empire were threatening to elect an anti-emperor who would do something about the rebels if Bogislaw didn’t help them.

My point is, the Munsterians were on the verge of breaking themselves, and so they were hardly in a position to impose crushing terms against the French. Because of this, the changes in territory at the end of the war was surprisingly small. The Rhinemouthers would annex Picardy, which they had briefly held in a dynastic union twenty years beforehand, and Guise to the Rhinemouths proper, while the County of Rethel would be subject to the Duchy of Luxembourg, which was in personal union under Philip II. South-eastern Champagne would be annexed into the Duchy of Lorraine, while the Duchy of Bar would be broken off and given over to Bogislaw’s youngest son, Barnim[4]. There were also a number of fairly minor border arrangements, with several Munsterian states annexing a few castles or towns along the border. The Duchy of Brittany would also have its independence restored to it, with the complex chain of marriages and suspicious deaths that had once nearly brought it into personal union with France wound up placing Pedro de Navarre, former regent of Navarre, upon the Breton throne. Finally, an incredible amount of money would be paid to the Munsterians, equivalent to the total income of the French crown for a year, to be distributed amongst the states of the League ‘for the benefit of all’. Most of this money was taken by Philip to pay back his money-lenders, but enough made it to the smaller states to allow them to at least start paying down their debts. Such a large indemnity severely weakened the strength of both France at large and Charles himself, and the increased taxes needed to make up the balance and keep the state running merely exacerbated the ongoing peasant uprisings across France.

And, finally, there was the Treaty of Savona, conducted between France and the Marians in early 1524 after several months of tenuous negotiations. The Marians were doubtlessly victorious in the region, having effectively driven the French and their allies from the peninsula almost entirely on their own. Because of this, they were rather arrogant and, despite Hyginus’ best attempts at diplomacy, it was nearly impossible to establish internal agreement, which made presenting a united front towards the French, to say the least. At long last, the Pope was able to wrangle his supporters and met with Charles personally at Savona in August 1523.

Savona and Lombardy, as steadfast allies of the French, would be shown little mercy. Savona’s mainland territory would be halved, with Genoa being reclaimed by the Calvians[5] and everything east of Rapallo being annexed by Tuscany. However, they would be allowed to rebuild their fleet to as great extent as they pleased, and they kept most of their trading posts in the western Mediterranean, albeit because of logistical problems in transferring them to Calvi or Venice rather than any legitimate mercy. Hyginus would recognize Giovanni Comnini, who was elected as doge in 1525, as legitimate Lord of Savona a few weeks later, and the Savonese would join the Trinitarian Coalition against the barbaries a few years down the road. Naples would be officially recognized as the possession of the former Ferdinand III of Aragon, and in a later treaty between Duarte, Ferdinand and Hyginus, Sardinia, Sicily and the Balearic Islands would all be recognized as de jure territory of Naples, marking an effective reversal of the dynastic situation of previous centuries.

However, the most dramatic impact of the Treaty of Savona was in northern Italy itself. Lombardy, as both a kingdom and as a state, would be dismembered in its entirety. Venice would regain most of its pre-invasion territory along the Po plain, except for Mantua, which more than doubled its mainland holding with the stroke of a pen. That most of this region was a burned-out wreck of its former self, as was most of northern Italy by this point, does not seem to have bothered the Doge. The island fortress of Ile-du-Roi would be razed and its weapons distributed amongst the Marian states, with all of the Marian states agreeing to prevent the construction of any fortress here in the future, which would prevent the passage of vessels up the river. Modena would expand itself greatly, annexing Parma and Ferrara from Lombardy. By now, the region had been so devastated by the back-and-forth fighting that Ferrara was the only halfway decent city left, and so it became the capital of the newly-established Grand Duchy of the Four Cities. Urbino also gained new territories, being awarded the fortress city of Mantua in what was almost certainly a calculated effort to turn the Urbinians and the Modenese against each other and thus allow Hyginus to wield more influence over them both. The Tuscans would move their border further north, to the northern foothills of the Apennines, securing them a defensible frontier and a great deal of influence over the regions to their north. And, of course, new states were carved out of Lombardy. The Duchy of Savoy was returned to its exiled dynasty, stradling lands in both the lowlands of Italy, the Alps, and the lowlands of Provence. The Duchy of Alessandria was carved out around the city of the same name, its ruler being a friend of Hyginus named Alessandro Agostino Lascaris[6]. The Counties of Piacenza and Cremona were also established, once again around the cities of the same name, and were made the segnorities of Fredrico di Gonzago, the exiled descendant of the former Dukes of Mantua. More importantly as far as Hyginus was concerned, he had been one of his closest political allies in Rome and had helped in the defense of the city against the army of the Borgias. The city of Como, Hyginus’ former residence during his time as a cardinal, was annexed into the Papal States, while Avignon and Benevento were restored to Roman control. Finally, the remnant of the Kingdom of Lombardy was formerly reduced to the Duchy of Milan, and Massimiliano Sforza, the son of the last native duke, was restored to the Milanese throne.

The Duchy of Provence would also be raised to a state in personal union with France, rather than an integral part of it as it had been before. This had little immediate impact, but Hyginus intended for it to complicate the relations between the two states and turn it into a quagmire that would reduce its value as a staging point. No money would change hands, however, as Hyginus sensed the financial weakness of the French monarchy and feared that destabilizing it would only worsen the ongoing crisis, a fear that had far more justification than he knew. Finally, on the far side of the Adriatic, the secondary Epirote theater of the war was also brought to a close at Savona. The Epirotes had been a Neapolitan protectorate before the war, and upon the outbreak of the war they had been attacked by the Venetians and the Venetian-allied Albanians and Moreotes. When the war in Naples had spiraled out into civil war, Epirus too had collapsed into civil war between the French-aligned Carlo III and the Aragonese-aligned Ferrante. Ferrante had triumphed after receiving support from the Venetians, but he was a puppet of the Serene Republic because of it. The Venetians would annex Vonitsa, Preveza and all the islands of the region, while the Albanians would seize everything north of Ottoman-held Sarandoz and the Moreotes would annex Missolonghi and the lands around the Aitoliko lagoon.

While the War of the Three Leagues was over, a time of great strife had only just begun. Central France and much of Germany[7] were consumed by revolts as hungry and angry peasants rose up against their oppressors in hopes of ending centuries of oppression. In the east, Hungary, Austria and Serbia had all been devastated by a long-running civil war between the newly-ascended Ladislaus V and his brother Janos[8], the prosperity of the Raven’s reign wiped away in a few scant years. Across Europe, many thousands lay dead from hunger and hundreds of thousands struggled to survive, their lands and homes wrecked by the shadow of war or raids from neighboring states. With the chief maritime powers of the Mediterranean engaged in a death-struggle, the barbary corsairs had had a field day, ravaging the coasts of the western Mediterranean and enslaving thousands. The common people of Europe were tired, desperate and disillusioned, having watched their sons and brothers march to their deaths for the sake of some petty noblemen. The fires of revolt burned across much of the region, but it was only with the publication of the 67 Articles of Ulrich Zwingli that these fires would rise into an all-consuming inferno….

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] The Hundred Year’s War ended in 1458 ITTL, so there is far less impetus for 1453 to be considered the close of the era. The survival of the Moreotes and Trapezuntines also weakens the argument that it ended the Byzantine Empire, so the Fall of Constantiople, while still significant, isn’t as important.

[2] OTL’s Louis XII

[3] OTL Francis I. I’m using the modern form of his name here, btw, he wrote his name ‘Francoys’.

[4] The succession laws of Pomerania dictated that each son would receive an equal amount of their father’s land unless they were awarded appenages before his death. Bogislaw intended his eldest son, Kasmir/Conrad to succeed him as Duke of Pomerania and Brunswick and Anna as Duke of Brandenburg, and so gave appenages to his other three sons; Georg, his second son, became Duke of Anhalt, and his fourth son, Otto, became Burgrave of Donha.

[5] Genoa was by now so thoroughly wrecked by five subsequent battles during the War of the Three Leagues that it was effectively useless, and Calvi remained the capital of the republic. It is likely that Hyginus advocated this in hopes of further involving Calvi in mainland affairs, so that he could use it as a counterbalance against the Venetians.

[6] Alessandrio is a female-line descendant of Ioannes Vatatzes, but still used the prestigious Lascaris surname because, after all, who was going to stop him? Vatatzes’ ghost?

[7] The Bundschuh Movement occurred as in OTL, but the spark of the Bauernkrieg was not Luther’s writing as in OTL but rather several years of drought and famine that exacerbated the already tyrannical tax systems of the Carinthian lords. Joss Fritz and his peasant army kicked off the Bauernkrieg proper with their sack of Heidelberg in 1519, and since then a mixture of insurgencies and outright revolts have crippled central and southern Germany, with no signs of stopping. The Second Jacquerie began when the self-defense groups that had been organized to drive off the Munsterian raiders in central France were attacked by their own lords, who feared organized peasants more than they did enemy raiders.

[8] They had a civil war off camera, I couldn’t work myself up to actually make an update for a periphery conflict after spending so much time writing and rewriting the sections on the War of the Three Leagues.

Last edited:

Are these Zaporozhian freebooters? Were they significant this early?over-eager cossacks

Have you told us how the Ottoman civil war ended?

Isn't this massively counterproductive for the Iberians? They wanted to reduce Aragon, not build it. Earlier you mentioned Aragon was losing everything but Valencia in the peninsula.The counties of Foix and Commiges would also be given over to Aragon, as well as Toulouse and the lands immediately surrounding it. Rodez would also be ceded to Aragon, but would remain as an exclave from the kingdom proper.

On the other hand, I can totally see them using this as an excuse to take more Aragonese territory within Iberia, and compensating them with formerly French land.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 96 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part LXXIV: Dueling Patriarchs (1545-1547) Appendix: The Apocalypse of David Part LXXV: The White Horse (1551-1553) Part LXXVI: The Invasion of Syria (1553-1554) Part LXXVII: Armageddon (1554-1555) Appendix: al-Sirozi Part LXXVIII: Long Live the Aftokrator? (1556-1559) On the Future of the Timeline- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: