I suppose I should say the newspaper article in the preceding chapter was taken verbatim from the Front Page of the November 4, 1914 edition of the Victoria Daily Colonist, lest I be banned and/or sued for plagiarism.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Rainbow. A World War One on Canada's West Coast Timeline

- Thread starter YYJ

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 257 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Appendix 5: Diving the Wrecks of Barclay Sound Appendix 6: Introduction Appendix 6 Part 1: The Warships Appendix 6 part 2: The Liners Appendix 6 Part 3: The freighters Appendix 6 part 5: Conclusions Appendix 7: CBC Radio Program Morningside Interview Book Club Questions.Not going to lie, I busted out laughing at this point. Perfect example of someone being too quick to action and not thinking things through beforehand.It only took a couple of days for the British consul in Lima to initiate legal action against the Bengrove, claiming that the freighter was not a German merchant seeking shelter, but was instead a British flagged war prize taken by the Germans, and thus under the Hague 13 Convention of 1907, Article 21, was required to either leave port after 24 hours or have her crew interned by Peruvian authorities and the ship released back to her British owners, Joseph Hoult and Co, of Liverpool.

Saxonia’s former captain countered by saying that Bengrove was brought into the neutral port for want of fuel and provisions, which was explicitly allowed under Article 21, but would happily comply and leave port if he was sold coal to steam to the nearest German port, as also provided for under the Article. After reading the newspapers he determined the nearest German port not captured or besieged by Entente forces was Wilhelmshaven.

Afterwards: Voyage of SMS Niagara, Part 4

Nov 19, 1914. SMS Niagara,

SS BENGROVE REPORTS KOSMOS LINE MERCHANTS LUXOR ANUBIS RHAKOTIS UARDA MARIE IN CALLAO HARBOUR AVAILABLE AS AUXILIARIES STOP PERU WILL NOT PERMIT GERMAN MERCHANTS TO PURCHASE COAL BUT WE ARE CONSOLIDATING AVAILABLE COAL TO SINGLE SHIP PLEASE ADVISE STOP

Captain Von Schönberg received this message on Niagara in the Gulf of Guayaquil, attempting to interdict the Chilean nitrate trade to Britain and France. After nightfall the same day he received further reports.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS IN WIRELESS CONTACT WITH HAPAG LINER ABESSINA IN PISAGU CHILE STOP ABESSINIA REPORTS KOSMOS LINER OSIRIS AND HAMBURG SA LINER CAP VERDE ALSO PRESENT STOP CHILE WILL ALLOW GERMAN MERCHANTS TO PURCHASE COAL STOP

SS BENGROVE REPORTS HAPAG LINER ABESSINIA IN WIRELESS CONTACT WITH HAMBURG SA LINERS SANTA MARIA IN CALETA BUENA CHILE AND SANTA THERESA IN IQUIQUE STOP ETAPPENDIEST ORGANIZATION ATTEMPTING TO PURCHASE COAL PLEASE ADVISE STOP

“Very good,” Von Schönberg said to Lieutenant Riedeger. “We may not have to rely on captured coal after all, if the crew of Bengrove and the Etappendeist phantoms are able to arrange auxiliaries for us.” He chose not to respond at the moment, to avoid any chance of giving away Niagara’s position.

The vagaries of atmospherics caused Von Schönberg to miss another wireless message.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS SHIPPING STOP ON ALL ENTENTE MERCHANT TRAFFIC WEST COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA IN RESPONSE TO GERMAN VICTORY AT BATTLE OFF CORONEL

For the next couple of weeks Niagara plied the shipping lanes from Guayaquil as far south as Antofagasta, in hopes of catching Entente ships carrying saltpeter, but Von Schönberg was disappointed. No Entente merchants were encountered, but Niagara spotted a good number of Chilean vessels: tramps, ships of the Compania Sud America de Vapores, and the occasional ship of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, now flying the Chilean flag. He suspected that most of these ships were loaded with nitrates, some even with copper ore or refined copper, bound for British ports. Von Schönberg also knew that PSNC was a company headquartered in Liverpool, despite the ships now flying the Chilean flag.

A German warship was within its rights during wartime to stop and search a vessel to determine her true country of registry. And if the vessel was a belligerent, to seize the ship as a prize. Furthermore, Niagara could also stop and search any neutral vessel, and if it was found that the cargo was on the list of absolute contraband, or on the list of conditional contraband and was bound for a belligerent country, then the cargo could be seized and, under the exigency of wartime, the ship could be sunk if no other option was available.

But Von Schönberg did not want to get into the business of molesting Chilean flagged vessels. Chile was, of the countries in the region, one of the most favourably disposed to Germany. Chile had a sizable German population, and at this point 4 months into the war, was still willing to sell coal to German ships that were clearly operating as naval auxiliaries, despite protests and obstruction from British agents. Von Schönberg did not want to jeopardize this relationship. Furthermore, Chile had a substantial navy, with several cruisers of her own, the Chacabuco, Presidente Errazuriz, Blanco Encalada, Ministoro Zentano, and the new armoured cruiser O’Higgins, as well as a good number of torpedo boats and destroyers, and even an old ironclad battleship, the Capitan Pratt. If he antagonized Chile he could find these warships either escorting coastal traffic, or even assigned to hunt him down.

So Von Schönberg continued to prowl the coast, looking for ships flying the Red Ensign or Tricolore, in vain. He kept his distance from the neutral merchants. Six days were spent in high seas and terrible weather with zero visibility. Niagara continued to receive sporadic updates on the status of available German auxiliaries sheltering in Chile’s harbours, and on November 28 finally received a message that had Von Schönberg abandon his current hunting grounds.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS SHIPPING STOP STILL IN PLACE ON ALL ENTENTE MERCHANT TRAFFIC WEST COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA

Dec 3, 100 NM South of the Azuero Peninsula, Panama.

Niagara stopped the 4300 ton Nippon Yusen Kaisha cargo liner Bombay Maru, bound from New Orleans to Yokohama with a cargo of scrap iron, distilling equipment, and industrial chemicals. The crew of 38 were brought onboard Niagara, all useful provisions transferred, and the ship was kept alongside for a day while 300 tons of coal were brought up from the Bombay Maru’s bunkers and swung across between ships by Niagara’s derricks. Finally the ship was scuttled with demolition charges. This caused a spectacular show of multicoloured smoke and flame as the chemicals in the holds caught fire.

Dec 6, 150 NM South of the Azuero Peninsula, Panama.

Niagara captured the 4900 ton Indra Line steam freighter Inverclyde, steaming east towards the Panama Canal. Inverclyde was carrying frozen lamb, wool, and bales of cotton ultimately bound for Liverpool. Inverclyde’s crew of 41 and 12 passengers and 2 dogs, a lab and a heeler, were brought aboard and shown to the secure accommodations on Niagara’s lower decks. Nine of the passengers were found to be British reserve junior officers and NCOs returning to join their units, and were officially taken prisoner of war, although they were not segregated from the civilian interned crews or treated differently.

Niagara hove-to alongside Inverclyde all that day and the next while 10 tons of lamb were swung across to be put in Niagara’s freezers, the freighter had her pantries emptied, and 200 tons of coal was loaded into sacks and hoisted aboard and into Niagara’s bunkers. On the evening of the December 8th, Inverclyde was sunk with demolition charges.

No sooner had Invercylde disappeared beneath the waves than another smoke trail was spotted to the north. Von Schönberg ordered Niagara to be put on a course to intercept. The smoke was travelling west, and in an hour a single funnel and pair of masts appeared over the horizon to the north-west.

“Ship is flying the Red Ensign,” announced a sharp-eyed lookout. “Looks to be of around 3000 tons.” The sun was very low in the sky, and within a half hour the bright disk would sink into the Pacific.

“Set our course to match that ship,” ordered Von Schönberg. “We will not be able to catch her before sunset, but if she is on a regular course, we should meet her again at dawn.” As soon as the glare from the sunset was snuffed out by the sea, the lookout called again.

“Two smoke trails due west!” the lookout reported.

“My, what a busy stretch of water,” responded Von Schönberg. “I suppose it is one of the most crowded shipping lanes in the world, what with this new canal.” He was silent for a moment, then added, “Maintain course, let me know the moment you have anything new to say about the fresh sightings.” He looked around. Niagara was trailing the single funneled freighter, and was herself now mostly lost to the British merchant lookouts against the dark eastern sky, while the British freighter was becoming a one-dimensional silhouette in the fading light. If the new smoke trails resolved themselves into ships before the light faded completely to night, they would be black outlines backlit against the pink sky, while Niagara would be invisible in the darkness to the east.

Twenty minutes later the lookout announced “Two pairs of masts. Ships are travelling in company, one mile apart. Course to the south-east.” Von Schönberg observed with his own binoculars, but the lookout had a 10 meter height advantage. After a few long minutes, he saw the tips of two pairs of masts emerge from the line of the horizon.

A moment later the lookout called, “second ship in line is showing… a spotting top. Two spotting tops.”

“Helm!” ordered Von Schönberg. “Set coarse due south. Full speed!” Niagara began to heel over as she entered into the turn.

“Second ship has tripod masts, fore and aft,” reported the lookout. Von Schönberg felt the revolutions of Niagara’s engines come up, and despite the urgency of the situation couldn’t help but notice how smooth the machinery felt.

“Second ship has three funnels,” continued the lookout, “widely spaced but even. First funnel is taller.” A moment later he reported, “First ship has four funnels, closely spaced masts and funnels swept. Freighter is signaling to the new ships by Morse light… Identifies herself as SS Roddam. Second ship is responding. Second ship says…” the lookout read slowly as he translated the Morse “Fall into line 1 mile astern. Will meet rest of squadron and colliers at Pinas Bay.”

“Rest of squadron…” repeated Von Schönberg. “That there is an Indefatigable class battle cruiser. Most likely HMS Australia. And some kind of Town class small cruiser.”

Niagara had now worked up to her full speed of just over 18 knots. Not fast enough, thought Von Schönberg, and still, we are burning coal at a horrible rate. The British warships continued to close, but it became apparent they were steaming at cruising speed, that they were not on an intercept course, and by the time nautical dusk arrived, Niagara was well to the south of their track, unseen in the darkness.

Indefatigable class silhouette

Town Class Silhouette

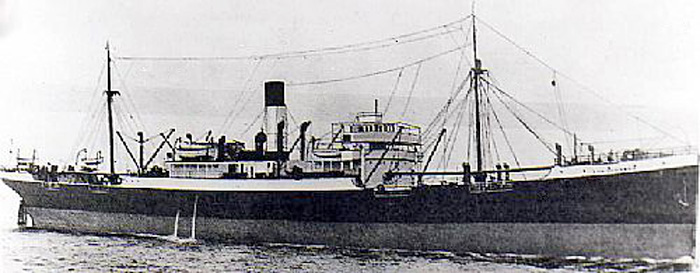

SS Inverclyde

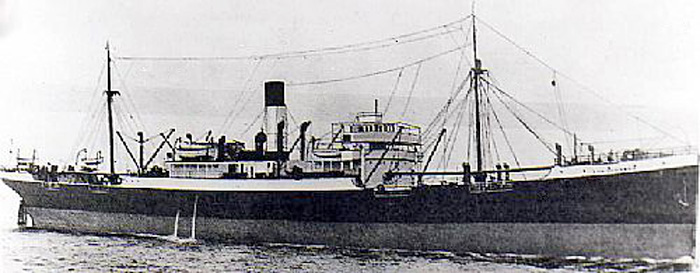

SS Roddam

SS BENGROVE REPORTS KOSMOS LINE MERCHANTS LUXOR ANUBIS RHAKOTIS UARDA MARIE IN CALLAO HARBOUR AVAILABLE AS AUXILIARIES STOP PERU WILL NOT PERMIT GERMAN MERCHANTS TO PURCHASE COAL BUT WE ARE CONSOLIDATING AVAILABLE COAL TO SINGLE SHIP PLEASE ADVISE STOP

Captain Von Schönberg received this message on Niagara in the Gulf of Guayaquil, attempting to interdict the Chilean nitrate trade to Britain and France. After nightfall the same day he received further reports.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS IN WIRELESS CONTACT WITH HAPAG LINER ABESSINA IN PISAGU CHILE STOP ABESSINIA REPORTS KOSMOS LINER OSIRIS AND HAMBURG SA LINER CAP VERDE ALSO PRESENT STOP CHILE WILL ALLOW GERMAN MERCHANTS TO PURCHASE COAL STOP

SS BENGROVE REPORTS HAPAG LINER ABESSINIA IN WIRELESS CONTACT WITH HAMBURG SA LINERS SANTA MARIA IN CALETA BUENA CHILE AND SANTA THERESA IN IQUIQUE STOP ETAPPENDIEST ORGANIZATION ATTEMPTING TO PURCHASE COAL PLEASE ADVISE STOP

“Very good,” Von Schönberg said to Lieutenant Riedeger. “We may not have to rely on captured coal after all, if the crew of Bengrove and the Etappendeist phantoms are able to arrange auxiliaries for us.” He chose not to respond at the moment, to avoid any chance of giving away Niagara’s position.

The vagaries of atmospherics caused Von Schönberg to miss another wireless message.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS SHIPPING STOP ON ALL ENTENTE MERCHANT TRAFFIC WEST COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA IN RESPONSE TO GERMAN VICTORY AT BATTLE OFF CORONEL

For the next couple of weeks Niagara plied the shipping lanes from Guayaquil as far south as Antofagasta, in hopes of catching Entente ships carrying saltpeter, but Von Schönberg was disappointed. No Entente merchants were encountered, but Niagara spotted a good number of Chilean vessels: tramps, ships of the Compania Sud America de Vapores, and the occasional ship of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, now flying the Chilean flag. He suspected that most of these ships were loaded with nitrates, some even with copper ore or refined copper, bound for British ports. Von Schönberg also knew that PSNC was a company headquartered in Liverpool, despite the ships now flying the Chilean flag.

A German warship was within its rights during wartime to stop and search a vessel to determine her true country of registry. And if the vessel was a belligerent, to seize the ship as a prize. Furthermore, Niagara could also stop and search any neutral vessel, and if it was found that the cargo was on the list of absolute contraband, or on the list of conditional contraband and was bound for a belligerent country, then the cargo could be seized and, under the exigency of wartime, the ship could be sunk if no other option was available.

But Von Schönberg did not want to get into the business of molesting Chilean flagged vessels. Chile was, of the countries in the region, one of the most favourably disposed to Germany. Chile had a sizable German population, and at this point 4 months into the war, was still willing to sell coal to German ships that were clearly operating as naval auxiliaries, despite protests and obstruction from British agents. Von Schönberg did not want to jeopardize this relationship. Furthermore, Chile had a substantial navy, with several cruisers of her own, the Chacabuco, Presidente Errazuriz, Blanco Encalada, Ministoro Zentano, and the new armoured cruiser O’Higgins, as well as a good number of torpedo boats and destroyers, and even an old ironclad battleship, the Capitan Pratt. If he antagonized Chile he could find these warships either escorting coastal traffic, or even assigned to hunt him down.

So Von Schönberg continued to prowl the coast, looking for ships flying the Red Ensign or Tricolore, in vain. He kept his distance from the neutral merchants. Six days were spent in high seas and terrible weather with zero visibility. Niagara continued to receive sporadic updates on the status of available German auxiliaries sheltering in Chile’s harbours, and on November 28 finally received a message that had Von Schönberg abandon his current hunting grounds.

SS BENGROVE REPORTS SHIPPING STOP STILL IN PLACE ON ALL ENTENTE MERCHANT TRAFFIC WEST COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA

Dec 3, 100 NM South of the Azuero Peninsula, Panama.

Niagara stopped the 4300 ton Nippon Yusen Kaisha cargo liner Bombay Maru, bound from New Orleans to Yokohama with a cargo of scrap iron, distilling equipment, and industrial chemicals. The crew of 38 were brought onboard Niagara, all useful provisions transferred, and the ship was kept alongside for a day while 300 tons of coal were brought up from the Bombay Maru’s bunkers and swung across between ships by Niagara’s derricks. Finally the ship was scuttled with demolition charges. This caused a spectacular show of multicoloured smoke and flame as the chemicals in the holds caught fire.

Dec 6, 150 NM South of the Azuero Peninsula, Panama.

Niagara captured the 4900 ton Indra Line steam freighter Inverclyde, steaming east towards the Panama Canal. Inverclyde was carrying frozen lamb, wool, and bales of cotton ultimately bound for Liverpool. Inverclyde’s crew of 41 and 12 passengers and 2 dogs, a lab and a heeler, were brought aboard and shown to the secure accommodations on Niagara’s lower decks. Nine of the passengers were found to be British reserve junior officers and NCOs returning to join their units, and were officially taken prisoner of war, although they were not segregated from the civilian interned crews or treated differently.

Niagara hove-to alongside Inverclyde all that day and the next while 10 tons of lamb were swung across to be put in Niagara’s freezers, the freighter had her pantries emptied, and 200 tons of coal was loaded into sacks and hoisted aboard and into Niagara’s bunkers. On the evening of the December 8th, Inverclyde was sunk with demolition charges.

No sooner had Invercylde disappeared beneath the waves than another smoke trail was spotted to the north. Von Schönberg ordered Niagara to be put on a course to intercept. The smoke was travelling west, and in an hour a single funnel and pair of masts appeared over the horizon to the north-west.

“Ship is flying the Red Ensign,” announced a sharp-eyed lookout. “Looks to be of around 3000 tons.” The sun was very low in the sky, and within a half hour the bright disk would sink into the Pacific.

“Set our course to match that ship,” ordered Von Schönberg. “We will not be able to catch her before sunset, but if she is on a regular course, we should meet her again at dawn.” As soon as the glare from the sunset was snuffed out by the sea, the lookout called again.

“Two smoke trails due west!” the lookout reported.

“My, what a busy stretch of water,” responded Von Schönberg. “I suppose it is one of the most crowded shipping lanes in the world, what with this new canal.” He was silent for a moment, then added, “Maintain course, let me know the moment you have anything new to say about the fresh sightings.” He looked around. Niagara was trailing the single funneled freighter, and was herself now mostly lost to the British merchant lookouts against the dark eastern sky, while the British freighter was becoming a one-dimensional silhouette in the fading light. If the new smoke trails resolved themselves into ships before the light faded completely to night, they would be black outlines backlit against the pink sky, while Niagara would be invisible in the darkness to the east.

Twenty minutes later the lookout announced “Two pairs of masts. Ships are travelling in company, one mile apart. Course to the south-east.” Von Schönberg observed with his own binoculars, but the lookout had a 10 meter height advantage. After a few long minutes, he saw the tips of two pairs of masts emerge from the line of the horizon.

A moment later the lookout called, “second ship in line is showing… a spotting top. Two spotting tops.”

“Helm!” ordered Von Schönberg. “Set coarse due south. Full speed!” Niagara began to heel over as she entered into the turn.

“Second ship has tripod masts, fore and aft,” reported the lookout. Von Schönberg felt the revolutions of Niagara’s engines come up, and despite the urgency of the situation couldn’t help but notice how smooth the machinery felt.

“Second ship has three funnels,” continued the lookout, “widely spaced but even. First funnel is taller.” A moment later he reported, “First ship has four funnels, closely spaced masts and funnels swept. Freighter is signaling to the new ships by Morse light… Identifies herself as SS Roddam. Second ship is responding. Second ship says…” the lookout read slowly as he translated the Morse “Fall into line 1 mile astern. Will meet rest of squadron and colliers at Pinas Bay.”

“Rest of squadron…” repeated Von Schönberg. “That there is an Indefatigable class battle cruiser. Most likely HMS Australia. And some kind of Town class small cruiser.”

Niagara had now worked up to her full speed of just over 18 knots. Not fast enough, thought Von Schönberg, and still, we are burning coal at a horrible rate. The British warships continued to close, but it became apparent they were steaming at cruising speed, that they were not on an intercept course, and by the time nautical dusk arrived, Niagara was well to the south of their track, unseen in the darkness.

Indefatigable class silhouette

Jane’s Fighting Ships, 2nd ed. : Jane, Fred T. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Source: Asiatic Society of MumbaiIdentifier: BK_00109542Digitization Sponsor: Observer Research Foundation

archive.org

Town Class Silhouette

Jane’s Fighting Ships, 2nd ed. : Jane, Fred T. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Source: Asiatic Society of MumbaiIdentifier: BK_00109542Digitization Sponsor: Observer Research Foundation

archive.org

SS Inverclyde

Screw Steamer INVERCLYDE built by Charles Connell & Company in 1906 for Royden & Company, (T. B. Royden, manager), Liverpool. , Cargo

Screw Steamer INVERCLYDE built by Charles Connell & Company in 1906 for Royden & Company, (T. B. Royden, manager), Liverpool. , Cargo 1929 Sold to T. W. Ward Ltd., Sheffield, for demolition at their Inverkeithing facility. October 1929.

www.clydeships.co.uk

SS Roddam

Last edited:

OK, here is an alternate alternate history POD that would affect the unfolding of this timeline:

In our timeline, and in this timeline, the Chilean navy refused to accept the submarines Antofagasta and Iquique from the shipyard in Seattle, and the boats were snapped up at the last moment before the declaration of war by the government of British Columbia and became the Royal Canadian Navy submarines HMCS CC-1 and CC-2.

But what if Chile had accepted the boats, despite their known faults? Then the two submarines would have already been delivered at the start of this story, and would appear on the list of Chilean Navy vessels in the previous chapter. They would not be available to bolster the defences of Vancouver, Victoria, and Esquimalt.

IOTL, the submarines provided a morale boost, and an early core to an emergent RCN submarine fleet, but saw no action. ITTL, their absence would mean that the Princess Charlotte and Nürnberg would not be torpedoed. Nürnberg had accumulated considerable damage from other adversaries, but her condition was much more in the balance than she was at the end of Aug 21, 1914, ITTL. Would Von Schönberg scuttle her, or continue on?

Asking this “What If?” for a moment makes me realize how ASB the appearance of those subs for sale at that particular time was, and the whole acquisition process. Would you have believed it if I made that up? Often our actual history is the most bizarre.

In our timeline, and in this timeline, the Chilean navy refused to accept the submarines Antofagasta and Iquique from the shipyard in Seattle, and the boats were snapped up at the last moment before the declaration of war by the government of British Columbia and became the Royal Canadian Navy submarines HMCS CC-1 and CC-2.

But what if Chile had accepted the boats, despite their known faults? Then the two submarines would have already been delivered at the start of this story, and would appear on the list of Chilean Navy vessels in the previous chapter. They would not be available to bolster the defences of Vancouver, Victoria, and Esquimalt.

IOTL, the submarines provided a morale boost, and an early core to an emergent RCN submarine fleet, but saw no action. ITTL, their absence would mean that the Princess Charlotte and Nürnberg would not be torpedoed. Nürnberg had accumulated considerable damage from other adversaries, but her condition was much more in the balance than she was at the end of Aug 21, 1914, ITTL. Would Von Schönberg scuttle her, or continue on?

Asking this “What If?” for a moment makes me realize how ASB the appearance of those subs for sale at that particular time was, and the whole acquisition process. Would you have believed it if I made that up? Often our actual history is the most bizarre.

Probably not, I'm guessing, but like the saying goes, "Truth is stranger than fiction".Asking this “What If?” for a moment makes me realize how ASB the appearance of those subs for sale at that particular time was, and the whole acquisition process. Would you have believed it if I made that up? Often our actual history is the most bizarre.

Loved this timeline, and the above question gave me a chance to reply with yet another well deserved LIKE.

Ta da! HMAS Australia and HMS Newcastle are is in their historically correct positions as per OTL, in the previous chapter.... Also what about HMAS Australia?

If SMS Niagara heads west towards Asian waters or French Polynesia, are there any isolated ports that are lightly enough defended to successfully attack but still large enough or located in a key spot that would be worth raiding and looting and destroying any local infrastructure or industry?

Von Spee bombarded Papeete with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on Sept 22, so the the main port of French Polynesia is already blasted.If SMS Niagara heads west towards Asian waters or French Polynesia, are there any isolated ports that are lightly enough defended to successfully attack but still large enough or located in a key spot that would be worth raiding and looting and destroying any local infrastructure or industry?

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau also pounced onto Apia in German Samoa, on Sept 14, after the ANZAC forces had captured it, hoping to surprise and sink any Entente ships they found there, but the ships had left, and the ANZAC troops on land were stronger than any landing party he could assemble, so he left.

OTL, Nürnberg attacked Fanning Island on Sept 7, and cut the Canada to Australia telegraph cable. But ITTL the cable has already been cut at the other end at Bamfield.

Fiji and Fanning Island were the only Royal Navy Coaling Stations in the Central Pacific.

Nauru in the Marshall Islands was a German Colony until captured by the Australians. Nauru was a major source of phosphates, an alternate source to Chile, and was brought into production by the Germans in 1907. It was considered important enough that 2 German surface raiders shelled the phosphate plant and port in Word War 2.

All of these places are very far away from where Niagara is now, but then Niagara was designed and built as a trans-Pacific liner.

Afterwards: Voyage of SMS Niagara, Part 5 Somber Christmas

Dec 9, 1914. SMS Niagara, off Punta Galera, Ecuador

When the star-filled night gave way to pre-dawn nautical twilight, the jungle-capped rolling hills of coastal Ecuador were visible on the southern horizon. Captain Von Schönberg was relieved to see that no trails of funnel smoke could be seen in any direction.

“Helm, take us south by south-west,” ordered Von Schönberg. “I want to get us long way away from here,” he said to Lientenant Riedeger. “With a British battle cruiser, a Town class cruiser, and ‘the rest of the squadron’ off Panama. Rest of the squadron… We might be wise to take Captain Therichen’s advice and steam in the wake of Prinz Eitel Friedrich to the Atlantic.”

“We will follow you to the ends of the earth, sir,” answered Riedeger cheerfully.

“There are a number of anchorages in this part of the world that fit that description,” replied Von Schönberg.

Dec 11, 250 MN off Punta Negra Peru

After running west and south for two days, Von Schönberg risked a short wireless message, attempting to arrange to meet with a collier. Before then he planned to disappear into the wide Pacific, for a while, to let the local situation cool down.

He received a reply later that day in naval code.

SS LUXOR WILL HAVE KOSMOS SS NEGADA AND HAPAG SS THESSALIA CURRENTLY IN VALPARAISO HARBOUR TO RENDEZVOUS AT Y IN 10 DAYS TIME STOP

Y was the pre-agreed upon code name for Más a Tierra in the Juan Fernandez Islands, an isolated group of islands off Chile’s coast where Admiral Von Spee had coaled his cruisers on two occasions since October.

December 13th and 14th Niagara encountered a terrible storm, that carried away a couple of her lifeboats, and tore off the false funnel extensions of her SS Arcadian disguise. When the storm blew itself out, and repairs were made to the ship, Von Schönberg had her repainted to resemble the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique liner SS La Champagne, with red funnels with black bands at the top. Far off the coast of Chile, and far from any shipping lanes, the Germans did not expect to encounter any ships, and they did not.

Dec 21, 40 NM Northwest of Más A Tiera Island.

The weather was clear, with frilly high cloud, and Von Schönberg thought he could see a bit of lower cloud in the distance, hinting at the location of the island still over the horizon. No smoke from ships was in sight, and none was expected to be yet. The Juan Fernandez group, Von Schönberg knew, had two barely habitable islands of any size, and a scattering of rocky hazards to navigation. Más A Fuera, to the west, was host to a Chilean prison. Más A Tiera, the easternmost and largest of the islands, had a fishing village and a decent anchorage at Cumberland Bay. Niagara still had in the neighborhood of 500 tons of coal on board, but Von Schönberg wished to keep her bunkers as full as possible, to give him the most freedom of action. He and his navigator were looking at a chart when a wireless runner entered the bridge.

“Sir, we are receiving a strong signal, in military code. Very close.”

“British?” Von Schönberg asked.

“Not possible to tell, sir,” replied the runner, “but certainly not anything of ours.” He left the bridge.

“Helm,” ordered Von Schönberg. “Come about. Take us due north.”

A minute later the runner reappeared. “We just received this sir, in our merchant code.”

SS NEGADA BEING APPROACH…

“The rest was lost to interference sir,” said the runner. “Someone is jamming the airwaves. Very loud and close.”

“Bring us up to 18 knots,” ordered Von Schönberg. “Someone has nicked our colliers.”

Niagara steamed back north, never having seen her destination.

Dec 25. 300 NM off Coquimbo, Chile.

The crew of Niagara marked a somber Christmas. Fuel and supplies were low, but the cooks managed to make a passable feast nonetheless, serving the last of the frozen lamb from SS Inverclyde. The captured crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru shared in the feast and festivities, in their own quarters, even though only 2 of the Japanese crew were Christians.

Dec 28. 300 NM off Trujillo, Peru.

At dawn Von Schönberg sent a wireless message attempting to contact SS Luxor, where Bengrove’s prize crew had relocated, in Callao harbor. He had entrusted a naval codebook with the junior wireless operator, so he sent the message in naval code. If he got no response he would have to risk merchant code to try and reach any of the other German merchants within range. As it was he received a reply in the afternoon.

SS LUXOR UNABLE TO BRING COAL STOP PERU PROHIBITING GERMAN MERCHANTS FROM CLEARING PORT WITH COAL WE CAN LEAVE PORT WITH PROVISIONS AND MEDICAL SUPPLIES CAN RENDEZVOUS AT W IN 4 DAYS

W was the pre-arranged code name for the Galapagos Islands.

Dec 30, 1914. Tagus Cove, Albermarle Island, Galapagos Islands.

Niagara had steamed at 10 knots all the way from the Juan Fernandez Islands to the Galapagos, in order to conserve coal. With the coal remaining on board Von Schönberg had the option of interning in Callao, Peru, in Ecuador, or in one of the northern Chilean ports. He was not happy to have such limited freedom of action, nor was he happy to be sitting at anchor.

Albermarle Island, sometimes called Atternave, was the largest of the Galapagos Islands. The landmass of the island was made of six interconnected major volcanoes that took the shape of a seahorse on the chart. And a very desolate place indeed, Von Schönberg thought. Semi-circular Tagus Cove itself looked to be a flooded volcanic crater. Across a 4 kilometer wide channel rose Narborough Island, another single giant volcanic cone. The terrain was rough and jagged, and sparsely covered with scrub vegetation.

The crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru had had become a hardship for the Germans, adding another 79 mouths to feed, but Von Schönberg had had no opportunity to send the men ashore or release them anywhere. Landing parties were sent to hunt for food, as supplies were low. Galapagos tortoises were a traditional mariner’s food source when provisioning at the Islands, on account of them being able to survive for long periods of time tipped over on their backs in a ship’s hold, and thus a storable fresh source of meat. But Niagara had refrigerators and freezers. A hunting party located a sea lion rookery, and returned towing a raft of sleek carcasses, some weighing up to 300 kilograms. Shore parties found some stupid birds easy to catch, but the more skilled hunters bagged dozens of feral goats and pigs and even a few cattle. So more exotic foodstuffs like iguana, penguins, and the already mentioned tortoises were left alone.

The New Year was welcomed to the smell of fragrant stew, while the officers were served pork tenderloin.

Jan 3, 1915. Tagus Cove.

SS Luxor, a Kosmos freight liner of 7000 GRT, arrived in the late morning. Her captain was very apologetic that he had not been allowed to supply coal.

“The Peruvians are becoming stricter by the week,” reported Luxor’s captain. “I believe they are feeling the iron heel of British diplomacy. Now they are even talking about impounding our wireless antennae for the duration of the conflict. Ever since the loss at the Falklands…”

“The Falklands?” asked Von Schönberg.

“Oh,” said Luxor’s captain, “you do not know.” He paused gravely. “Admiral Von Spee’s squadron was destroyed by the British at the Falkland Islands.” Von Schönberg took off his hat. “On December 8th,” Luxor’s captain continued, “All of the cruisers were sunk, except for Dresden. I am told there were very few survivors.”

Von Schönberg stared at the horizon. “And of Dresden?” he asked, stone faced.

“The British are hunting for her everywhere,” said the merchant captain. “Furiously. But they are most active around Terra del Fuego. Our ships in Punta Arenas, Puerto Montt and Corral are reporting Royal Navy sightings frequently. The Brits have their work cut out for them. That part of the coast is a maze of forests and mountains and endless channels.”

“Yes,” said Von Schönberg. “I was in a place like that recently. British Columbia, in Canada.”

“I have heard rumors that Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Sierra Cordoba is supplying Dresden, but it is best I do not know too much about that.”

Crews were already transferring bags and boxes of provisions from Luxor. Sides of beef. Flour and potatoes and root vegetables. Canned food. A trove of newspapers in English and German. Supplies for the ship’s hospital, and, paradoxically not objected to by the Peruvian customs officers, rifle ammunition. Luxor’s captain had even ordered all the coal he could possibly spare to be bagged for transfer. That amounted to 50 tons, and left him the most bare margin to return to Callao.

“We transferred most of our spare coal from the 5 German ships in Callao over to the liner Rhakotis, for just such a moment as this. Then when the time came, Peruvian customs would not let her sail. But Chile is much more willing to turn a blind eye. The Etappendeist organization has arranged for the HAPAG freighter Abessina, to take on a load of coal for you. She is in Pisagua now, and will be following us in 4 days time. Abessina was acting as an auxiliary for Admiral Von Spee, rest his soul, in October, so her crew know how to coal a warship away from a proper port.”

“Good,” said Von Schönberg. “Take your time getting back to Callao. I want to be well and truly gone from here before these British and Japanese sailors get to tell their stories.”

Von Schönberg had the captured crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru sent over to Luxor, and the freighter steamed south down Urbina Bay, and out to sea. Nürnberg’s former junior wireless operator remained aboard, to facilitate communication.

Jan 6, 1915. Tagus Cove.

SS ABESSINIA REPORTS COAL SHIPMENT DELAYED STOP APPARENTLY A LANDSLIDE HAS BLOCKED THE RAIL LINE TO PISAGU

Von Schönberg passed some of the time by reading newspapers Luxor had delivered. He learned Tsingtao had fallen to the Japanese in November, and most of the German colonies around the globe had been overcome, but German East Africa seemed to be holding out against all odds. Müller in Emden had led a swashbuckling charge around the Indian Ocean, only to be finally brought to battle and driven aground by an Australian cruiser in November. Looff in Königsberg, Nürnberg’s sister ship, had some initial successes before being cornered in the Rufiji Delta. Now he seemed to be attempting to tie up as many British forces for as long as he could before the inevitable outcome. Graßhoff in Geier was interned in Honolulu, and Von Schönberg was frankly surprised he had made it that far in his clapped-out antique gunboat. Of the small cruisers loose at sea engaging in commerce raiding, only Köhler in Karlsruhe and Lüdecke in Dresden were still at large, whereabouts unknown.

Admiral Souchon, in Goeben and Breslau, seemed to have singlehandedly brought the Ottoman Empire into the war on the side of the Central Powers, and had turned the Black Sea into a German lake, although the Kaiserliche Marine crews had politely put on fezes and changed their ship’s names to Turkish ones. Armed liners as commerce raiders seemed to be hitting their stride, their long legs making them less dependent on frequent coaling. Kronprinz Wilhelm and Prinz Eitel Friedrich were having some successes in the South Atlantic, but Kormoran had achieved nothing and interned herself in Guam when she ran out of coal. Niagara’s name appeared in the papers from time to time, but only speculatively. The last concrete report on her came from captured Entente merchant crews who had been landed at Callao November 19.

The land war, which Von Schönberg only bothered to read about when he had exhausted news of naval matters, had become static. Germany had failed to knock France out in the initial offensives, and in the east, after an initial scare, had stabilized the front with Russia. So if the land war was now one of attrition, reasoned Von Schönberg, any damage he could do to the Entente war making capacity was valuable.

www.google.ca

www.google.ca

SS Negada

SS Abessinia

When the star-filled night gave way to pre-dawn nautical twilight, the jungle-capped rolling hills of coastal Ecuador were visible on the southern horizon. Captain Von Schönberg was relieved to see that no trails of funnel smoke could be seen in any direction.

“Helm, take us south by south-west,” ordered Von Schönberg. “I want to get us long way away from here,” he said to Lientenant Riedeger. “With a British battle cruiser, a Town class cruiser, and ‘the rest of the squadron’ off Panama. Rest of the squadron… We might be wise to take Captain Therichen’s advice and steam in the wake of Prinz Eitel Friedrich to the Atlantic.”

“We will follow you to the ends of the earth, sir,” answered Riedeger cheerfully.

“There are a number of anchorages in this part of the world that fit that description,” replied Von Schönberg.

Dec 11, 250 MN off Punta Negra Peru

After running west and south for two days, Von Schönberg risked a short wireless message, attempting to arrange to meet with a collier. Before then he planned to disappear into the wide Pacific, for a while, to let the local situation cool down.

He received a reply later that day in naval code.

SS LUXOR WILL HAVE KOSMOS SS NEGADA AND HAPAG SS THESSALIA CURRENTLY IN VALPARAISO HARBOUR TO RENDEZVOUS AT Y IN 10 DAYS TIME STOP

Y was the pre-agreed upon code name for Más a Tierra in the Juan Fernandez Islands, an isolated group of islands off Chile’s coast where Admiral Von Spee had coaled his cruisers on two occasions since October.

December 13th and 14th Niagara encountered a terrible storm, that carried away a couple of her lifeboats, and tore off the false funnel extensions of her SS Arcadian disguise. When the storm blew itself out, and repairs were made to the ship, Von Schönberg had her repainted to resemble the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique liner SS La Champagne, with red funnels with black bands at the top. Far off the coast of Chile, and far from any shipping lanes, the Germans did not expect to encounter any ships, and they did not.

Dec 21, 40 NM Northwest of Más A Tiera Island.

The weather was clear, with frilly high cloud, and Von Schönberg thought he could see a bit of lower cloud in the distance, hinting at the location of the island still over the horizon. No smoke from ships was in sight, and none was expected to be yet. The Juan Fernandez group, Von Schönberg knew, had two barely habitable islands of any size, and a scattering of rocky hazards to navigation. Más A Fuera, to the west, was host to a Chilean prison. Más A Tiera, the easternmost and largest of the islands, had a fishing village and a decent anchorage at Cumberland Bay. Niagara still had in the neighborhood of 500 tons of coal on board, but Von Schönberg wished to keep her bunkers as full as possible, to give him the most freedom of action. He and his navigator were looking at a chart when a wireless runner entered the bridge.

“Sir, we are receiving a strong signal, in military code. Very close.”

“British?” Von Schönberg asked.

“Not possible to tell, sir,” replied the runner, “but certainly not anything of ours.” He left the bridge.

“Helm,” ordered Von Schönberg. “Come about. Take us due north.”

A minute later the runner reappeared. “We just received this sir, in our merchant code.”

SS NEGADA BEING APPROACH…

“The rest was lost to interference sir,” said the runner. “Someone is jamming the airwaves. Very loud and close.”

“Bring us up to 18 knots,” ordered Von Schönberg. “Someone has nicked our colliers.”

Niagara steamed back north, never having seen her destination.

Dec 25. 300 NM off Coquimbo, Chile.

The crew of Niagara marked a somber Christmas. Fuel and supplies were low, but the cooks managed to make a passable feast nonetheless, serving the last of the frozen lamb from SS Inverclyde. The captured crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru shared in the feast and festivities, in their own quarters, even though only 2 of the Japanese crew were Christians.

Dec 28. 300 NM off Trujillo, Peru.

At dawn Von Schönberg sent a wireless message attempting to contact SS Luxor, where Bengrove’s prize crew had relocated, in Callao harbor. He had entrusted a naval codebook with the junior wireless operator, so he sent the message in naval code. If he got no response he would have to risk merchant code to try and reach any of the other German merchants within range. As it was he received a reply in the afternoon.

SS LUXOR UNABLE TO BRING COAL STOP PERU PROHIBITING GERMAN MERCHANTS FROM CLEARING PORT WITH COAL WE CAN LEAVE PORT WITH PROVISIONS AND MEDICAL SUPPLIES CAN RENDEZVOUS AT W IN 4 DAYS

W was the pre-arranged code name for the Galapagos Islands.

Dec 30, 1914. Tagus Cove, Albermarle Island, Galapagos Islands.

Niagara had steamed at 10 knots all the way from the Juan Fernandez Islands to the Galapagos, in order to conserve coal. With the coal remaining on board Von Schönberg had the option of interning in Callao, Peru, in Ecuador, or in one of the northern Chilean ports. He was not happy to have such limited freedom of action, nor was he happy to be sitting at anchor.

Albermarle Island, sometimes called Atternave, was the largest of the Galapagos Islands. The landmass of the island was made of six interconnected major volcanoes that took the shape of a seahorse on the chart. And a very desolate place indeed, Von Schönberg thought. Semi-circular Tagus Cove itself looked to be a flooded volcanic crater. Across a 4 kilometer wide channel rose Narborough Island, another single giant volcanic cone. The terrain was rough and jagged, and sparsely covered with scrub vegetation.

The crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru had had become a hardship for the Germans, adding another 79 mouths to feed, but Von Schönberg had had no opportunity to send the men ashore or release them anywhere. Landing parties were sent to hunt for food, as supplies were low. Galapagos tortoises were a traditional mariner’s food source when provisioning at the Islands, on account of them being able to survive for long periods of time tipped over on their backs in a ship’s hold, and thus a storable fresh source of meat. But Niagara had refrigerators and freezers. A hunting party located a sea lion rookery, and returned towing a raft of sleek carcasses, some weighing up to 300 kilograms. Shore parties found some stupid birds easy to catch, but the more skilled hunters bagged dozens of feral goats and pigs and even a few cattle. So more exotic foodstuffs like iguana, penguins, and the already mentioned tortoises were left alone.

The New Year was welcomed to the smell of fragrant stew, while the officers were served pork tenderloin.

Jan 3, 1915. Tagus Cove.

SS Luxor, a Kosmos freight liner of 7000 GRT, arrived in the late morning. Her captain was very apologetic that he had not been allowed to supply coal.

“The Peruvians are becoming stricter by the week,” reported Luxor’s captain. “I believe they are feeling the iron heel of British diplomacy. Now they are even talking about impounding our wireless antennae for the duration of the conflict. Ever since the loss at the Falklands…”

“The Falklands?” asked Von Schönberg.

“Oh,” said Luxor’s captain, “you do not know.” He paused gravely. “Admiral Von Spee’s squadron was destroyed by the British at the Falkland Islands.” Von Schönberg took off his hat. “On December 8th,” Luxor’s captain continued, “All of the cruisers were sunk, except for Dresden. I am told there were very few survivors.”

Von Schönberg stared at the horizon. “And of Dresden?” he asked, stone faced.

“The British are hunting for her everywhere,” said the merchant captain. “Furiously. But they are most active around Terra del Fuego. Our ships in Punta Arenas, Puerto Montt and Corral are reporting Royal Navy sightings frequently. The Brits have their work cut out for them. That part of the coast is a maze of forests and mountains and endless channels.”

“Yes,” said Von Schönberg. “I was in a place like that recently. British Columbia, in Canada.”

“I have heard rumors that Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Sierra Cordoba is supplying Dresden, but it is best I do not know too much about that.”

Crews were already transferring bags and boxes of provisions from Luxor. Sides of beef. Flour and potatoes and root vegetables. Canned food. A trove of newspapers in English and German. Supplies for the ship’s hospital, and, paradoxically not objected to by the Peruvian customs officers, rifle ammunition. Luxor’s captain had even ordered all the coal he could possibly spare to be bagged for transfer. That amounted to 50 tons, and left him the most bare margin to return to Callao.

“We transferred most of our spare coal from the 5 German ships in Callao over to the liner Rhakotis, for just such a moment as this. Then when the time came, Peruvian customs would not let her sail. But Chile is much more willing to turn a blind eye. The Etappendeist organization has arranged for the HAPAG freighter Abessina, to take on a load of coal for you. She is in Pisagua now, and will be following us in 4 days time. Abessina was acting as an auxiliary for Admiral Von Spee, rest his soul, in October, so her crew know how to coal a warship away from a proper port.”

“Good,” said Von Schönberg. “Take your time getting back to Callao. I want to be well and truly gone from here before these British and Japanese sailors get to tell their stories.”

Von Schönberg had the captured crews of Inverclyde and Bombay Maru sent over to Luxor, and the freighter steamed south down Urbina Bay, and out to sea. Nürnberg’s former junior wireless operator remained aboard, to facilitate communication.

Jan 6, 1915. Tagus Cove.

SS ABESSINIA REPORTS COAL SHIPMENT DELAYED STOP APPARENTLY A LANDSLIDE HAS BLOCKED THE RAIL LINE TO PISAGU

Von Schönberg passed some of the time by reading newspapers Luxor had delivered. He learned Tsingtao had fallen to the Japanese in November, and most of the German colonies around the globe had been overcome, but German East Africa seemed to be holding out against all odds. Müller in Emden had led a swashbuckling charge around the Indian Ocean, only to be finally brought to battle and driven aground by an Australian cruiser in November. Looff in Königsberg, Nürnberg’s sister ship, had some initial successes before being cornered in the Rufiji Delta. Now he seemed to be attempting to tie up as many British forces for as long as he could before the inevitable outcome. Graßhoff in Geier was interned in Honolulu, and Von Schönberg was frankly surprised he had made it that far in his clapped-out antique gunboat. Of the small cruisers loose at sea engaging in commerce raiding, only Köhler in Karlsruhe and Lüdecke in Dresden were still at large, whereabouts unknown.

Admiral Souchon, in Goeben and Breslau, seemed to have singlehandedly brought the Ottoman Empire into the war on the side of the Central Powers, and had turned the Black Sea into a German lake, although the Kaiserliche Marine crews had politely put on fezes and changed their ship’s names to Turkish ones. Armed liners as commerce raiders seemed to be hitting their stride, their long legs making them less dependent on frequent coaling. Kronprinz Wilhelm and Prinz Eitel Friedrich were having some successes in the South Atlantic, but Kormoran had achieved nothing and interned herself in Guam when she ran out of coal. Niagara’s name appeared in the papers from time to time, but only speculatively. The last concrete report on her came from captured Entente merchant crews who had been landed at Callao November 19.

The land war, which Von Schönberg only bothered to read about when he had exhausted news of naval matters, had become static. Germany had failed to knock France out in the initial offensives, and in the east, after an initial scare, had stabilized the front with Russia. So if the land war was now one of attrition, reasoned Von Schönberg, any damage he could do to the Entente war making capacity was valuable.

Google Maps

Find local businesses, view maps and get driving directions in Google Maps.

www.google.ca

www.google.ca

SS Negada

SS Abessinia

Afterwards: Voyage of SMS Niagara, Part 5 The Battle of The Galapagos Islands

Jan 12, 1915. Tagus Cove.

Von Schönberg projected an image of calm resolve, sometimes even jovial optimism to his crew. But in private he felt his nerves stretched as tight as piano wires. Niagara had been sitting at anchor for almost two weeks, waiting for coal. If a Galapagos fisherman had pro-Entente sentiments he could have run up the sail on his fishing smack and reported Niagara’s position at the front desk of the British legation in Guayaquil by now, he thought. So he was tremendously relieved when SS Abessinia arrived in the afternoon.

“That was a very strange series of events,” Abessinia’s captain told Von Schönberg when they met. “A landslide put the rail line out of service, just as our trainload of coal was just due to arrive. A major landslide, and it happened in the absence of a storm, or any other natural cause. The rumor is it was some kind of sabotage. I half expect British agents hired local gangsters to pull off the caper.”

“I do hope the rail line is cleared soon,” said Abessinia’s captain, smiling. “We were forced to buy the entire coal supply for Pisagua’s power plant. It is amazing what some people will do for the right amount of money. If the train does not get through in the next day the town will run out of electricity, and the nitrate processing and loading facilities will grind to a halt.”

“You are leaving a trail of interesting stories in your wake,” said Von Schönberg. “People will paying attention.”

“We made sure the rumors circulated that we were headed for San Felix, in the Desventuradas Islands.”

“I have been there,” said Von Schönberg. “Not a bad ruse. That must be 1200 miles from here.”

“We were escorted for 2 days by a Chilean destroyer” continued Abessinia’s captain, until it had to return to port for fuel.”

The sounds of the coaling operation getting started entered into Niagara’s captain’s cabin.

“We are grateful,” said Von Schönberg.

“Keep doing what you are doing. You are a phantom. If the newspapers are at all truthful, the British know you are out there somewhere, but have no idea where.”

All that day, and into the next afternoon the coaling continued, until Niagara had received 1800 tons in her bunkers.

Jan 14, 1915. Galapagos Islands.

At dawn Niagara steamed out of Elizabeth Bay and left the Galapagos Islands behind her. Abessinia, riding high in the water in ballast, steamed south to loiter for a few days before returning to a Chilean Port. Her captain had been finding Pisagua a bit provincial for his tastes, and thought he might try to make for Valparaiso. Niagara steamed east.

Jan 16, 1915. 200 NM east of the Galapagos Islands.

This day came grey and overcast, with low cloud and occasional rain squalls. Despite having her drinking water tanks half full, Von Schönberg rigged tarpaulins to collect rain water. An hour after mid-day, Niagara spotted a smoke column, and set course to intercept. This proved to be a steam freighter of about 5000 tons with a single funnel, headed north. It did not take long to establish that the ship was flying the Red Ensign. The name painted on her bow read SS Trevanian. Niagara approached, and by Morse light ordered the freighter to stop and prepare to be boarded. The ship began to transmit a distress signal, which Niagara jammed.

Trevanian appeared to acknowledge that Niagara was both faster and obviously armed, and slowed before a warning shot was fired. Niagara stopped alongside, and launched boats to take the boarding party across. The boarding partly occupied Trevanian’s bridge and machinery spaces. By examining the ship’s log and manifest they learned that her cargo was anthracite coal, her holds were currently about half full with 2000 tons of coal aboard, that she was serving as a collier for the Royal Navy, and that her crew had already opened her seacocks and irrevocably started to scuttle her. Von Schönberg ordered Trevanian’s crew over to Niagara, but their captain refused, and insisted on launching his own lifeboats.

“This is strange,” said Von Schönberg to Lieutenant Riedeger. No land was in sight. The mainland of Ecuador was 400 nautical miles to the east. “We may have made a mistake. Recover the boarding party!”

“Ship!” shouted a lookout. “To the south! A liner with 2 funnels! Intercept course! Range 20,000 meters.”

Von Schönberg aimed his own binoculars at the new ship, and saw her outline take shape as she emerged from a rain squall. The liner was big, as big as Niagara. Her form became distinct as she left the wall of rain behind. She had a big bone in her teeth and was making great clouds of smoke. Her hull was painted navy grey. From her mast head she flew the White Ensign. His boarding party were just getting back in their boats, over on Trevanian.

“Full speed!” he ordered. The engine telegraph clanged. “Helm, take us north when you have steerage! Action Stations!” he ordered, even though the crews were already standing by the guns. “Signals, send a message to our boats.” The Morse light flashed.

ROYAL NAVY ARMED MERCHANT CRUISER YOU ARE ON YOUR OWN GOD BLESS

He saw his men over in their boats stand and salute. Water churned under Niagara’s stern, as she accelerated from a standing start.

“Lookout, what armament can you see!” demanded Von Schönberg

“A pair of guns on the forward well deck,” reported the lookout. “A pair of guns on C deck forward. Any other armament is masked by the ship’s superstructure, sir. “Range 18,000 meters.”

Von Schönberg looked at the Niagara’s bridge chronometer. Six minutes had elapsed since the ship was first sighted. “Navigator! What is 2000 meters in six minutes?”

“Eighteen knots, sir,” answered the navigator, without hesitation.

“That Brit is as fast as us and has a head start,” Von Schönberg said to Riedeger. “She likely has 12cm or 15 cm guns, probably 8 in Royal Navy fashion. Our guns will have longer range, but I don’t expect them to shoot as well from this deck as they did from Nürnberg. Still, our gun crews should be in a different league than Royal Navy Reservists. We are not coming up to speed nearly fast enough. They will be in range before we make our top speed. I think a stern chase is best to start. It will reduce our profile as a target, and we have 2 guns that can fire directly astern. One thing about this engagement, we will not be leading the ship from inside an armoured conning tower.”

The crew of Trevanian and Niagara’s boarding party each bobbed on the swells in their respective lifeboats, the British in four boats and the Germans in two. They kept their distance from each other. They were still enemies at war, after all, and although there were more British sailors, the Germans were armed with rifles and carbines. But they shared in the perspective of watching the battle from the sidelines, as if at a football match, while Trevanian slowly sank behind them.

Niagara was about 2000 meters away from the boats and 12,000 meters from the Royal Navy armed merchant cruiser that the crew of Trevanian knew to be HMS Orama, when she fired the opening shots of the engagement that was subsequently known as the Battle of the Galapagos Islands, even though the Islands were well out of sight. The men in the boats saw the flash of the guns 5 seconds before they heard the sound. Niagara’s first ranging shots were long, and she corrected fire until her stern guns were straddling Orama by the 6th salvo. The range between the ships dropped rapidly, as Niagara was slow to gather speed. Pairs of waterspouts rose on each side of the British ship every 10 seconds, until, at 1535 hours, at a range of 9000 meters Niagara scored a hit on Orama’s boat deck with a 10.5 cm High Explosive shell.

By coincidence or design, Orama chose this moment and range to return fire with her 4 forward 6 inch guns. Orama’s first shots fell short, and she spent several minutes finding the range, while Niagara continued to straddle her and landed the occasional shot, hitting Orama at the base of her first funnel, and in the second-class lounge at the front of the superstructure. A fire broke out on Orama’s boat deck, fanned by the speed of her travel. Both ships were still difficult targets at this point, since in a stern chase they were end-on to each other. By now the men in boats had to use binoculars to see any detail of the battle.

Orama’s first hit on Niagara could not have been more fortunate. A 6 inch High Explosive shell struck edge-on to the stern upper deck beside the P4 gun mount, and mowed down Niagara’s port aft gun crew with shell splinters and hull fragments. The range was down to 5000 meters, and although Niagara was now up to a speed of 14 knots, she was clearly not able to run from this engagement. At 1545 hours Captain Von Schönberg ordered Niagara to turn to starboard, to unmask her two starboard foc’stle guns. Orama matched the maneuver, and the two liners settled into parallel courses, and blasted away at each other from 5000 meters.

Niagara’s guns had a higher rate of fire and the crack German gun crews hit more often. Orama’s heavier shells did more damage with each hit. Soon both ships were on fire in a number of places. Orama’s P3 gun, on the after end of C-deck, suffered a major propellant fire as a dozen ready cartridges took light. This fire scattered the gun crew, and spread to the superstructure. Niagara’s aft funnel was knocked over, lubricating oil on her aft cargo derrick caught fire, and more fire broke out in the woodwork of her elegant first class dining room and the foredeck paint locker where the means of Niagara’s many consume changes was stored. The liners passed through a rain squall that helped to knock down the top deck fires. For several minutes the adversaries lost sight of each other, then emerged a mere 2000 meters apart, still on parallel courses.

Niagara’s gun crews could not miss at this range, and aiming for Orama’s waterline, landed 16 hits on the Royal Navy ship’s port hull in the space of a minute at, near, or below the waterline. Niagara’s gun in S2 position had ended up being served with a batch of armour piecing shells, and pumped them into Orama’s tall sides, penetrating through to the boiler rooms. This shooting gallery fusillade was cut short by one of Orama’s shells detonating against Niagara’s forward steam derrick machinery, killing or wounding both forward gun crews on the starboard broadside. The ships turned away from each other to open the range, and take stock of what urgent damage control could be affected. Both ships were on fire, holed below the waterline, and suffering machinery damage, but Orama was worse off on all three counts. Scenes inside both liners would not have been out of place in the pages of Danté’s Inferno.

Firehoses were brought into action on both ships. A momentary cease fire seemed to have taken place, and the liners circled each other at a range of 6,000 meters. As a few minutes passed it became clear that Orama was badly holed on her port side aft of the funnels, and began to show a list to port and to settle by the stern. Orama’s White Ensign still flew, and Captain Von Schönberg gave orders to try and find some way to communicate with the Royal Navy vessel to demand her surrender. Both liners had lost their wireless antennae and signal halyards, and drifting smoke from both ships obscured any sightlines for semaphore or Morse light, should any of the equipment still be working.

Smoke so interfered with visibility that when waterspouts began to rise from the sea again around Niagara, Von Schönberg first thought that Orama had resumed shooting, and he ordered Niagara’s surviving guns to return fire. But, he soon noticed, Orama’s guns were unmanned, and he saw no muzzle flashes. Through a momentary gap in the smoke he saw another ship, steaming from the south at full tilt, firing as she came, about 12,000 meters distant. This new enemy ship also took some time to find the range. He ordered the two remaining working guns that could be brought to bear to fire on the new target, but from his position on the bridge he had lost sight of the new ship in the smoke again, and a was not even able to identify his foe.

The new ship began to land hits on Niagara, but the smoke was hampering the British shooting as well, and most of the shells landed wide. The chief engineer reported to Von Schönberg through a voice tube that one boiler room was flooding, and another boiler had been hit and exploded, and the toppled funnel affected the draught, so he could not expect more than 12 knots, and probably less. Furthermore, although he had lost count, Niagara must have fired most of her ammunition by now, so he faced the real and humiliating possibility of running out of shells mid-battle.

When the smoke parted again to reveal this new foe, at a range of 8000 meters, Von Schönberg felt a sudden sense of calm, even Grace, wash over him. Through the smoke he saw the spotting tops, triple funnels, turrets and sponsons of a Royal Navy armoured cruiser. Perhaps of Monmouth Class? The Royal Navy had so many cruisers, they were hard to tell apart. In this moment, he had no duties left to discharge, he had done his utmost. He had no hand left to play at this point, and even if Niagara’s holds were full of ammunition, it would make no difference.

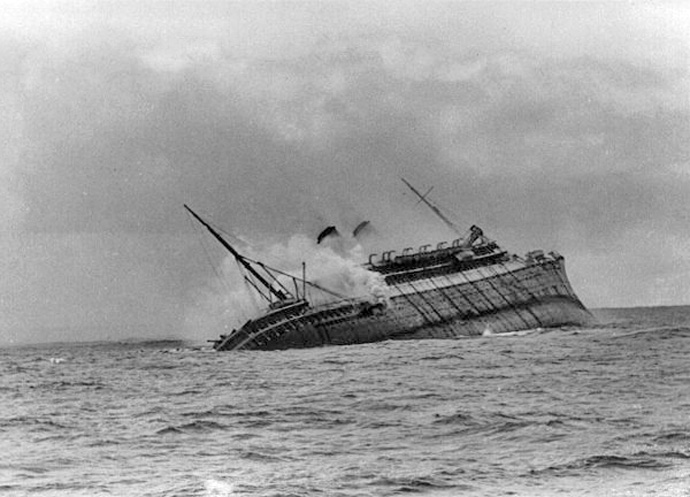

“Prepare scuttling charges, and abandon ship,” was his last order.

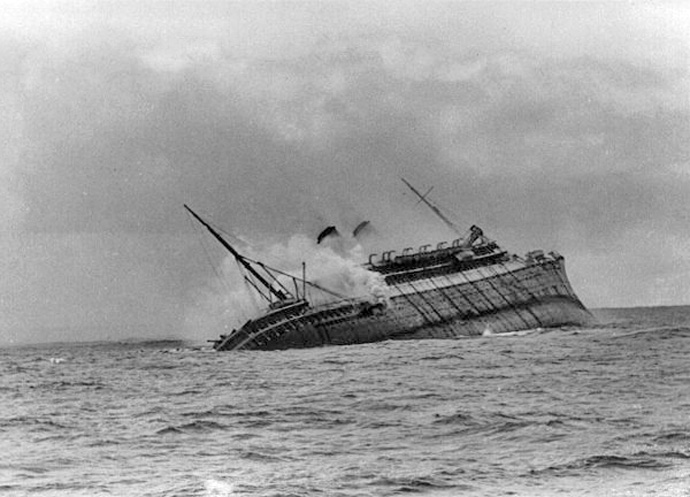

Niagara launched what boats remained, full of the surviving crew and as many wounded as could be rescued from the burning and flooding passageways below. As the boats pulled away, a demolition charge blew out the bottom of the forward hold and Niagara sank dramatically by the bow, throwing her stern high in the air before plunging into the deeps. Her Imperial Ensign still flew until the water closed over it. At the same moment, 5000 meters away, HMS Orama rolled over onto her side and sank.

HMS Kent stopped to pick up survivors from both sunken liners. Captain Karl Von Schönberg was not among them. He was not inclined to signal his surrender, had he even been able to, and one of Kent’s last salvoes had struck Niagara squarely on the bridge. HMS Kent picked up 108 survivors from Niagara, fewer from Orama, then noticed a flare and rescued the crew of her own collier Trevanian. Niagara’s boarding party raised the sails on their lifeboats and disappeared into a wall of rain, sailing themselves to Callao to join the crew on SS Luxor for the duration of the war.

– Fin –

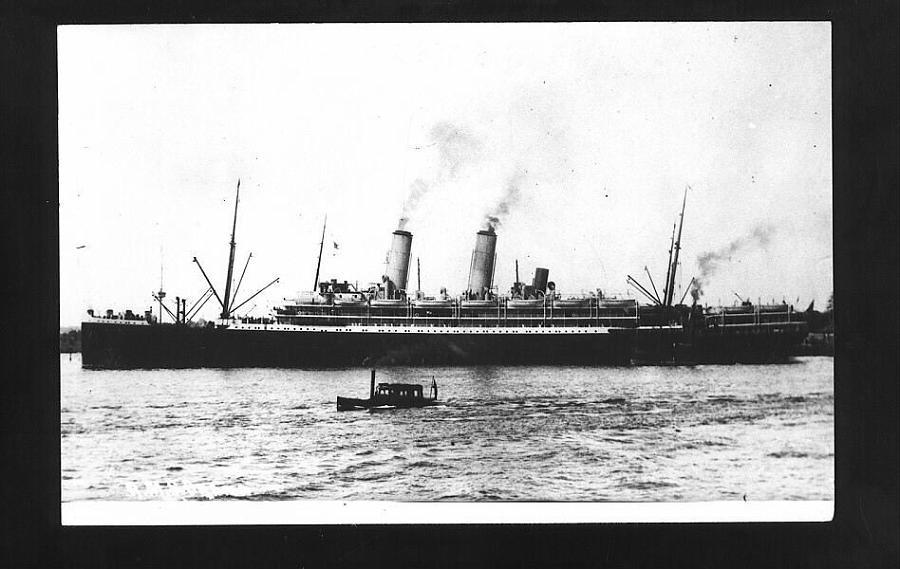

HMS Orama

HMS Kent

SMS Niagara sinking

alchetron.com

alchetron.com

HMS Orama sinking

Memorial for Captain Karl Von Schönberg

Von Schönberg projected an image of calm resolve, sometimes even jovial optimism to his crew. But in private he felt his nerves stretched as tight as piano wires. Niagara had been sitting at anchor for almost two weeks, waiting for coal. If a Galapagos fisherman had pro-Entente sentiments he could have run up the sail on his fishing smack and reported Niagara’s position at the front desk of the British legation in Guayaquil by now, he thought. So he was tremendously relieved when SS Abessinia arrived in the afternoon.

“That was a very strange series of events,” Abessinia’s captain told Von Schönberg when they met. “A landslide put the rail line out of service, just as our trainload of coal was just due to arrive. A major landslide, and it happened in the absence of a storm, or any other natural cause. The rumor is it was some kind of sabotage. I half expect British agents hired local gangsters to pull off the caper.”

“I do hope the rail line is cleared soon,” said Abessinia’s captain, smiling. “We were forced to buy the entire coal supply for Pisagua’s power plant. It is amazing what some people will do for the right amount of money. If the train does not get through in the next day the town will run out of electricity, and the nitrate processing and loading facilities will grind to a halt.”

“You are leaving a trail of interesting stories in your wake,” said Von Schönberg. “People will paying attention.”

“We made sure the rumors circulated that we were headed for San Felix, in the Desventuradas Islands.”

“I have been there,” said Von Schönberg. “Not a bad ruse. That must be 1200 miles from here.”

“We were escorted for 2 days by a Chilean destroyer” continued Abessinia’s captain, until it had to return to port for fuel.”

The sounds of the coaling operation getting started entered into Niagara’s captain’s cabin.

“We are grateful,” said Von Schönberg.

“Keep doing what you are doing. You are a phantom. If the newspapers are at all truthful, the British know you are out there somewhere, but have no idea where.”

All that day, and into the next afternoon the coaling continued, until Niagara had received 1800 tons in her bunkers.

Jan 14, 1915. Galapagos Islands.

At dawn Niagara steamed out of Elizabeth Bay and left the Galapagos Islands behind her. Abessinia, riding high in the water in ballast, steamed south to loiter for a few days before returning to a Chilean Port. Her captain had been finding Pisagua a bit provincial for his tastes, and thought he might try to make for Valparaiso. Niagara steamed east.

Jan 16, 1915. 200 NM east of the Galapagos Islands.

This day came grey and overcast, with low cloud and occasional rain squalls. Despite having her drinking water tanks half full, Von Schönberg rigged tarpaulins to collect rain water. An hour after mid-day, Niagara spotted a smoke column, and set course to intercept. This proved to be a steam freighter of about 5000 tons with a single funnel, headed north. It did not take long to establish that the ship was flying the Red Ensign. The name painted on her bow read SS Trevanian. Niagara approached, and by Morse light ordered the freighter to stop and prepare to be boarded. The ship began to transmit a distress signal, which Niagara jammed.

Trevanian appeared to acknowledge that Niagara was both faster and obviously armed, and slowed before a warning shot was fired. Niagara stopped alongside, and launched boats to take the boarding party across. The boarding partly occupied Trevanian’s bridge and machinery spaces. By examining the ship’s log and manifest they learned that her cargo was anthracite coal, her holds were currently about half full with 2000 tons of coal aboard, that she was serving as a collier for the Royal Navy, and that her crew had already opened her seacocks and irrevocably started to scuttle her. Von Schönberg ordered Trevanian’s crew over to Niagara, but their captain refused, and insisted on launching his own lifeboats.

“This is strange,” said Von Schönberg to Lieutenant Riedeger. No land was in sight. The mainland of Ecuador was 400 nautical miles to the east. “We may have made a mistake. Recover the boarding party!”

“Ship!” shouted a lookout. “To the south! A liner with 2 funnels! Intercept course! Range 20,000 meters.”

Von Schönberg aimed his own binoculars at the new ship, and saw her outline take shape as she emerged from a rain squall. The liner was big, as big as Niagara. Her form became distinct as she left the wall of rain behind. She had a big bone in her teeth and was making great clouds of smoke. Her hull was painted navy grey. From her mast head she flew the White Ensign. His boarding party were just getting back in their boats, over on Trevanian.

“Full speed!” he ordered. The engine telegraph clanged. “Helm, take us north when you have steerage! Action Stations!” he ordered, even though the crews were already standing by the guns. “Signals, send a message to our boats.” The Morse light flashed.

ROYAL NAVY ARMED MERCHANT CRUISER YOU ARE ON YOUR OWN GOD BLESS

He saw his men over in their boats stand and salute. Water churned under Niagara’s stern, as she accelerated from a standing start.

“Lookout, what armament can you see!” demanded Von Schönberg

“A pair of guns on the forward well deck,” reported the lookout. “A pair of guns on C deck forward. Any other armament is masked by the ship’s superstructure, sir. “Range 18,000 meters.”

Von Schönberg looked at the Niagara’s bridge chronometer. Six minutes had elapsed since the ship was first sighted. “Navigator! What is 2000 meters in six minutes?”

“Eighteen knots, sir,” answered the navigator, without hesitation.

“That Brit is as fast as us and has a head start,” Von Schönberg said to Riedeger. “She likely has 12cm or 15 cm guns, probably 8 in Royal Navy fashion. Our guns will have longer range, but I don’t expect them to shoot as well from this deck as they did from Nürnberg. Still, our gun crews should be in a different league than Royal Navy Reservists. We are not coming up to speed nearly fast enough. They will be in range before we make our top speed. I think a stern chase is best to start. It will reduce our profile as a target, and we have 2 guns that can fire directly astern. One thing about this engagement, we will not be leading the ship from inside an armoured conning tower.”

The crew of Trevanian and Niagara’s boarding party each bobbed on the swells in their respective lifeboats, the British in four boats and the Germans in two. They kept their distance from each other. They were still enemies at war, after all, and although there were more British sailors, the Germans were armed with rifles and carbines. But they shared in the perspective of watching the battle from the sidelines, as if at a football match, while Trevanian slowly sank behind them.

Niagara was about 2000 meters away from the boats and 12,000 meters from the Royal Navy armed merchant cruiser that the crew of Trevanian knew to be HMS Orama, when she fired the opening shots of the engagement that was subsequently known as the Battle of the Galapagos Islands, even though the Islands were well out of sight. The men in the boats saw the flash of the guns 5 seconds before they heard the sound. Niagara’s first ranging shots were long, and she corrected fire until her stern guns were straddling Orama by the 6th salvo. The range between the ships dropped rapidly, as Niagara was slow to gather speed. Pairs of waterspouts rose on each side of the British ship every 10 seconds, until, at 1535 hours, at a range of 9000 meters Niagara scored a hit on Orama’s boat deck with a 10.5 cm High Explosive shell.

By coincidence or design, Orama chose this moment and range to return fire with her 4 forward 6 inch guns. Orama’s first shots fell short, and she spent several minutes finding the range, while Niagara continued to straddle her and landed the occasional shot, hitting Orama at the base of her first funnel, and in the second-class lounge at the front of the superstructure. A fire broke out on Orama’s boat deck, fanned by the speed of her travel. Both ships were still difficult targets at this point, since in a stern chase they were end-on to each other. By now the men in boats had to use binoculars to see any detail of the battle.

Orama’s first hit on Niagara could not have been more fortunate. A 6 inch High Explosive shell struck edge-on to the stern upper deck beside the P4 gun mount, and mowed down Niagara’s port aft gun crew with shell splinters and hull fragments. The range was down to 5000 meters, and although Niagara was now up to a speed of 14 knots, she was clearly not able to run from this engagement. At 1545 hours Captain Von Schönberg ordered Niagara to turn to starboard, to unmask her two starboard foc’stle guns. Orama matched the maneuver, and the two liners settled into parallel courses, and blasted away at each other from 5000 meters.

Niagara’s guns had a higher rate of fire and the crack German gun crews hit more often. Orama’s heavier shells did more damage with each hit. Soon both ships were on fire in a number of places. Orama’s P3 gun, on the after end of C-deck, suffered a major propellant fire as a dozen ready cartridges took light. This fire scattered the gun crew, and spread to the superstructure. Niagara’s aft funnel was knocked over, lubricating oil on her aft cargo derrick caught fire, and more fire broke out in the woodwork of her elegant first class dining room and the foredeck paint locker where the means of Niagara’s many consume changes was stored. The liners passed through a rain squall that helped to knock down the top deck fires. For several minutes the adversaries lost sight of each other, then emerged a mere 2000 meters apart, still on parallel courses.

Niagara’s gun crews could not miss at this range, and aiming for Orama’s waterline, landed 16 hits on the Royal Navy ship’s port hull in the space of a minute at, near, or below the waterline. Niagara’s gun in S2 position had ended up being served with a batch of armour piecing shells, and pumped them into Orama’s tall sides, penetrating through to the boiler rooms. This shooting gallery fusillade was cut short by one of Orama’s shells detonating against Niagara’s forward steam derrick machinery, killing or wounding both forward gun crews on the starboard broadside. The ships turned away from each other to open the range, and take stock of what urgent damage control could be affected. Both ships were on fire, holed below the waterline, and suffering machinery damage, but Orama was worse off on all three counts. Scenes inside both liners would not have been out of place in the pages of Danté’s Inferno.

Firehoses were brought into action on both ships. A momentary cease fire seemed to have taken place, and the liners circled each other at a range of 6,000 meters. As a few minutes passed it became clear that Orama was badly holed on her port side aft of the funnels, and began to show a list to port and to settle by the stern. Orama’s White Ensign still flew, and Captain Von Schönberg gave orders to try and find some way to communicate with the Royal Navy vessel to demand her surrender. Both liners had lost their wireless antennae and signal halyards, and drifting smoke from both ships obscured any sightlines for semaphore or Morse light, should any of the equipment still be working.

Smoke so interfered with visibility that when waterspouts began to rise from the sea again around Niagara, Von Schönberg first thought that Orama had resumed shooting, and he ordered Niagara’s surviving guns to return fire. But, he soon noticed, Orama’s guns were unmanned, and he saw no muzzle flashes. Through a momentary gap in the smoke he saw another ship, steaming from the south at full tilt, firing as she came, about 12,000 meters distant. This new enemy ship also took some time to find the range. He ordered the two remaining working guns that could be brought to bear to fire on the new target, but from his position on the bridge he had lost sight of the new ship in the smoke again, and a was not even able to identify his foe.

The new ship began to land hits on Niagara, but the smoke was hampering the British shooting as well, and most of the shells landed wide. The chief engineer reported to Von Schönberg through a voice tube that one boiler room was flooding, and another boiler had been hit and exploded, and the toppled funnel affected the draught, so he could not expect more than 12 knots, and probably less. Furthermore, although he had lost count, Niagara must have fired most of her ammunition by now, so he faced the real and humiliating possibility of running out of shells mid-battle.