All I'm saying about future chapters at the moment is that the Klassenites won't be the most deranged group operating in Northwest Montana for long.A quick Google tells me..... oh dear.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Pale Horse: The Northwest Montana Insurgency and its Aftermath (1987-2002)

- Thread starter XTrapnel

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 49 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Five Days in May (1994) Part III: Suffering Shipwreck with Dignity Five Days in May (1994); Part IV - the Battle of Chicago Infobox: the May Crisis Creating a Reality for Ourselves where the Bleeding is (1994) Go, Ghost, Go (1994) Map: Northwest Montana during the Siege of Butte (1994) maybe SOMEONE will be able to see SOMETHING as it really is WATCHOUT (1994-5) The Sinews of Peace (1995-1997)Eugene Debs was an Indiana boy, wasn’t he?If anyone better versed in late 19th/early 20th century labour disputes can think of a suitably emblematic event which took place in Northern Indiana, Ohio or Michigan, I'll change the Steel Belt's name as well.

As a Texan, the issue with a Texarkana CSR is less that it’s not directly called Texas (I mean, it starts with “Tex”, seems close enough) than that it doesn’t include Texarkana, AR, or more broadly the Arkansas parts of that general region. An alternate name for West Texas could be Rio Grande.From my limited experience of Texans, I strongly suspect that they'd object more to no named state being called Texas than to the imposition of a hardline Syndicalist government, so I think the East Texas CSR ought to stay, but I agree on Texarkana.

>[in effect accusing LeVay of the sacrilege of simony]

>advanced contemporary post-Satanist theology in important ways

>PhD in political science, one of the most American in style of the social sciences

>genuine faith based motivation

>Now regarded as a moderate after the events of […] and the extensive […] operations in its wake

There is no exit possible from Mister Bones wild ride, and I question if I would disembark if it were possible.

I’m still working wiki but this guy is more dangerous than I thought. He is a leader who builds other leaders. He isn’t self important but promotes others to be greater than himself. He truly believes but knows that the church picnic and fundraiser ARE ALSO vital. His repeated retirements and acknowledgement of others ideas are really fucking dangerous. He’s literate and well read but still a true believer and humble about his works. This is a man who builds leaders greater than himself. This is a new theme in the nightmare for the syndicates and the poms.

>advanced contemporary post-Satanist theology in important ways

>PhD in political science, one of the most American in style of the social sciences

>genuine faith based motivation

>Now regarded as a moderate after the events of […] and the extensive […] operations in its wake

There is no exit possible from Mister Bones wild ride, and I question if I would disembark if it were possible.

I’m still working wiki but this guy is more dangerous than I thought. He is a leader who builds other leaders. He isn’t self important but promotes others to be greater than himself. He truly believes but knows that the church picnic and fundraiser ARE ALSO vital. His repeated retirements and acknowledgement of others ideas are really fucking dangerous. He’s literate and well read but still a true believer and humble about his works. This is a man who builds leaders greater than himself. This is a new theme in the nightmare for the syndicates and the poms.

Last edited:

Indiana Beach Crow

Monthly Donor

He was born and raised in Terre Haute, Indiana, and his house still stands on the Indiana State University campus. So yes, he would be enough of a local hero in this TL to have at least something named (or renamed) for him.Eugene Debs was an Indiana boy, wasn’t he?

Last edited:

Hm, I don't know if "Republic of Debs" rolls off the tongue half as well as Steel Belt does. Problem is that at least in the 1800s it seems like Chicago and Philly were the places in which big Old Northwest labor-history things were initiated (although I guess the AFL was founded in Cincinnati). If there was some term that could maybe encompass all of the figures that the government considers its founding fathers... the Knights?

I know Egypt has stuff like the 6th of October City, and I think there's other places named after dates-- maybe a "Republic of [date of important early pivotal Syndie victory]"?

I know Egypt has stuff like the 6th of October City, and I think there's other places named after dates-- maybe a "Republic of [date of important early pivotal Syndie victory]"?

Last edited:

Eugene Debs was an Indiana boy, wasn’t he?

Excellent catch. Forgot about him.

As a Texan, the issue with a Texarkana CSR is less that it’s not directly called Texas (I mean, it starts with “Tex”, seems close enough) than that it doesn’t include Texarkana, AR, or more broadly the Arkansas parts of that general region. An alternate name for West Texas could be Rio Grande.

You're completely right - mixed up my East and West Texases there for a minute...

I’m still working wiki but this guy is more dangerous than I thought.

I'm genuinely impressed if you managed to dig up information from Wikipedia, given the extent to which he (or someone connected to him) managed to scrub anything connected to him off the internet. I've been reduced to reading PDFs of his writings originally found on 4chan to get a handle on the man and his beliefs.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Set is the hit I located. I’m reading heavily into the theology of self expansion, a small teaching role, but most importantly his repeated stepping down from management roles in his organisation. The theology doesn’t seem as important as the organisational behaviour. And for an intelligence operative he seems to be aware of his functional limits as a leader.

Obviously allohistorically *the character may vary and engage with other theologies. But wherever he’s dropped he’s dangerously competent at building others it looks like.

I’m not a post satanist researcher by any stretch though and this is the first time I’ve encountered him outside chick tracts.

Obviously allohistorically *the character may vary and engage with other theologies. But wherever he’s dropped he’s dangerously competent at building others it looks like.

I’m not a post satanist researcher by any stretch though and this is the first time I’ve encountered him outside chick tracts.

Just a thought-New Orleans, and southern Louisiana in general, as part of "East Texas" strikes me as weird, considering that southern Louisiana can probably lay claim to the most divergent regional culture of anywhere in the US. Thinking about it, and factoring in the CSSA's very Soviet like obsession with making up categorizing ethnic groups and giving them their own little province, I'm surprised we don't have a Cajun CSR.

In a weird way, I could almost see parts of East Texas as part of a Louisiana CSR - Beaumont and Lake Charles are really not all that culturally distinct.Just a thought-New Orleans, and southern Louisiana in general, as part of "East Texas" strikes me as weird, considering that southern Louisiana can probably lay claim to the most divergent regional culture of anywhere in the US. Thinking about it, and factoring in the CSSA's very Soviet like obsession withmaking upcategorizing ethnic groups and giving them their own little province, I'm surprised we don't have a Cajun CSR.

Plenty of Soviet ASSRs (I'm especially thinking of Ukraine) have cross-cutting cultural regions in that same way, and I guess consolidating East Texas gets the prewar oil country and the offshore rigs in the same CSR. Still weird, though.

Haig's Gamble (1993)

Haig’s Gamble (1993)

In the end, it was a stubborn current account deficit, more than anything else, which killed the Combined Syndicates of America.

The CSA had attained the relative height of its prosperity following the end of the Second Weltkrieg: its Civil-War damaged industry largely reconstructed by the time Russian and Anglo-French soldiers were shaking hands across the Rhine in 1949, it was in a superb position, as the only large-scale industrial economy not essentially reduced to rubble, to become the world’s industrial powerhouse, while its decidedly unideological willingness to trade with anyone who could put up the money ensured that it retained this position well into the 60s. By the early 70s, however, the rest of the world was beginning to catch up: the Japanese-dominated Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere’s escalating industrialisation and Western Europe’s continuing recovery meant that the CSA no longer enjoyed the position that it once did.

A series of commodity shocks in the early 80s, for which the CSA’s key industries (by this point deeply complacent, starved of any real internal development over the preceding twenty years and coasting on thirty-year-old market dominance) were entirely unprepared, exacerbated the situation: when Robert McNamara was installed as Chairman in 1985, he was faced by increasing inflation, a stagnant industrial sector and a pool of reserve capital which had been whittled down alarmingly in recent years.

McNamara’s efforts to right the ship of American Syndicalism were three-pronged: firstly, at the urging of cyberneticist Anthony Stafford Beer, all enterprises above a certain size would be linked to a proposed distributed decision-making network, vastly increasing the economy’s ability to react to sudden changes in incentives; secondly, industrial management techniques originating outside the CSA would be incorporated into the CSA’s industrial sector; and finally, “syndicalist democracy” would be reintroduced on a limited scale for the first time since the early 1940s.

The first prong, resulting in the creation of CYBERSYN, proved of limited use due to the project’s technological limitations, and was largely defunded by the early 90s. The second prong, far more wide-ranging in its impact, was something of a success: the importation of just-in-time manufacturing techniques from Japan, and the introduction of the home-grown Six Sigma process improvement programme across a swathe of industries, helped the CSA regain some of the competitive edge that it had lost during its two decades of complacency (although these roll-outs sparked labour tensions – by 1990, the average worker in the CSA increasingly identified the Syndicalist Union Party’s higher-ups with those pencil-necked assholes in suits who timed your bathroom breaks.)

The third prong, involving the reintroduction of (indirect) elections for Governors of CSRs, had the most intriguing effects. The electoral process established for Gubernatorial elections was enormously convoluted, involving non-secret balloting of workplaces to elect delegates, who in turn elected a candidate (required to be a member of the Syndicalist Union Party in good standing nominated by at least one quarter of his CSR’s delegates to the Chamber of Syndicates and one fifth of his CSR’s union representative) to the office of Governor. This process, clearly intended to ensure that the Governorships remained in the hands of SUP loyalists, nevertheless provided the most accurate gauge of public opinion in the hinterlands for decades. The elections of November 1988, the first under this new system, saw candidates from the reformist wing of the SUP elected everywhere they stood (most notably, Max Baucus, James Stockdale and Dennis Kucinich). While subsequent elections in 1990 and 1992 weren’t quite as comprehensive a victory for any particular faction, it was clear by the time McNamara officially resigned his office in February 1993 that a significant level of factional discontent was bubbling below the serene surface of the SUP’s rule over the CSA.

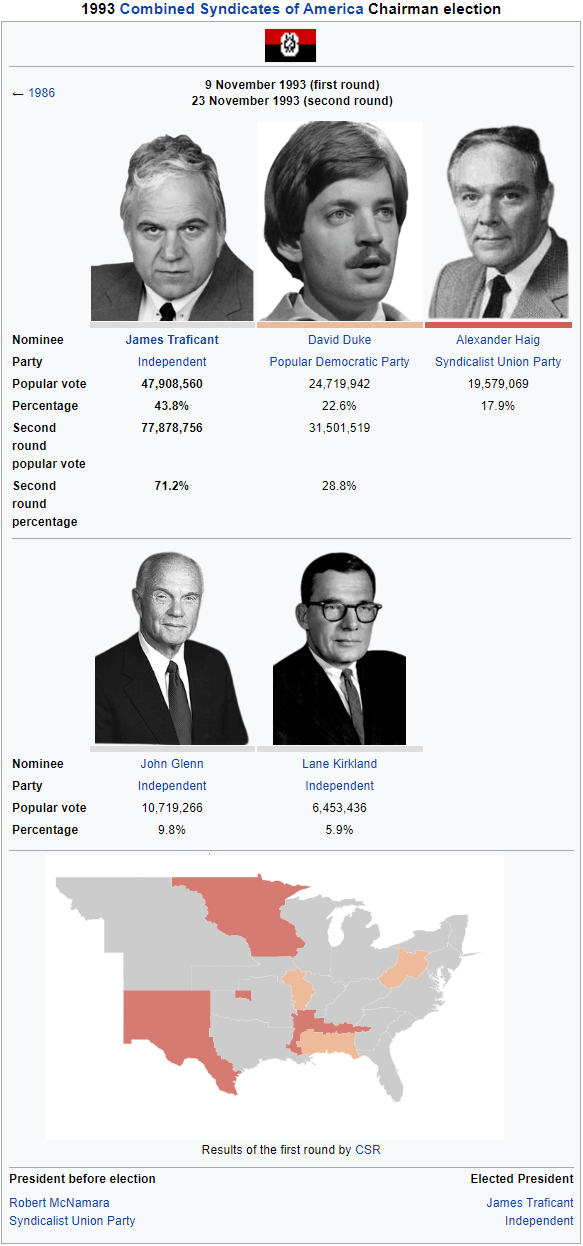

It was against this backdrop that Alexander Haig ascended to the office of Chairman in 1993: succeeding McNamara largely due to the lack of any obvious alternative, and still somewhat tainted by his close identification with the Northwest Montana Insurgency, he and his inner circle grasped the need to head off any challenge to his rule from within the SUP as soon as possible. The solution that he proposed was a surprisingly radical one. For the first time in fifty years, an open election would be held for the Chairmanship, with Haig running as the Syndicalist Union Party’s candidate: his inevitable and crushing victory over whatever handpicked opponent could be put forward as a plausible opposition standard-bearer, made possible by the SUP’s theoretically absolute control over what electoral infrastructure existed, would hopefully cement his hold on power.

The election, announced in March 1993, was scheduled for November. The process under which it would be conducted was designed to curtail the influence of the reformist faction to the greatest extent possible: in a break with McNamara’s system of “syndicalist democracy”, which would allow reformist Governors to exert pressure on voters in their CSRs, a secret ballot was instituted, with responsibility for tabulating the votes and ensuring the overall integrity of the election falling to a commission headed by the Speaker of the Chamber of Syndicates Walter Mondale (a man of decidedly orthodox Syndicalist views). Furthermore, the ban on parties other than the SUP from standing was lifted.

All that was missing now was an opponent, whom Haig’s connections in the Bureau of Internal Security were happy to provide. For ten years, David Duke had been a prominent and noisy critic of the SUP in the Gulf and Texarkana CSRs, rallying locals against the Chicago government and enjoying close but unspoken ties to “The Ragin’ Cajuns”, a small-scale terrorist group fighting for the creation of an ethnoseparatist Cajun CSR on the model of the New Afrika and Sequoyah CSRs. An astute observer would have noticed that his decade of public fulmination against governmental corruption and treachery had accomplished very little, and that, while many of his associates received significant custodial sentences, nothing particularly bad had happened to him. A very astute observer, willing to tail his car at irregular intervals to an assortment of back-roads in the Mississippi delta, would have – correctly – supposed him to be a long-standing informant for the Bureau of Internal Security. As a foil to Haig, he would be perfect.

Duke’s political grouping, the Popular Democratic Party, was granted certification within days by the CSA’s electoral commission, and provided with some public funding and guaranteed airtime on the CSA’s broadcasting system. As a hedge against the entrance of further candidates into the election, there would be two rounds of voting, the first to ensure that the CSA was forced into a binary choice between Haig and Duke. In comparison to Duke’s noisy entry into the race, the response of the SUP’s nascent reformist caucus was an altogether lower-key affair.

A loose assortment of Governors and Congressmen, brought together at first by their response to the Plains Massacre, had been holding regular discussions since late 1992: in response to Haig’s announcement, they agreed between themselves that one of their number should run for the post of Chairman. It was decided that this responsibility should ultimately fall to Congressman James Traficant, a locally-popular representative of broadly reformist sympathies. His nomination papers, signed by Governors Stockdale, Baucus and Kucinich, were received by the electoral commission in early April 1993, with his candidature being approved shortly afterwards: the SUP, untroubled by the addition of a minor politician to the list of candidates for Chairman, granted him funds and airtime without demur.

Forced into the unfamiliar environment of an election campaign, and unsure about the precise extent of their general popularity, the SUP was nevertheless initially sanguine about their prospects of victory: with polling suggesting that about 70% of the population wanted the reformist caucus to cooperate with the SUP rather than seize control over its apparatus, the Haig camp was more worried about what an overly decisive victory in the first round of voting would do to party unity than they were about the possibility of an unexpectedly close contest. That Haig had badly misread the public mood became clear in early July, when a series of internal polls suggested that Traficant had replaced Duke as Haig’s key opponent, and was within touching distance of first place.

The reaction by the SUP’s official campaign was one of blind panic. Traficant’s scheduled airtime and funding was abruptly pulled, with the electoral commission citing “financial discrepancies”; candidate nominations were reopened, with the previously apolitical John Glenn (pilot on the first manned spaceflight) and Lane Kirkland (head of the AFL, by now much diminished from its "One Big Union" days during Foster's chairmanship of the CSA) entering the election as fellow independents and immediately receiving sustained airtime; and a series of attack adverts against Traficant, alleging large-scale corruption, alcoholism and multiple marital infidelities, were launched by the SUP.

These interventions had little impact by this point in the electoral cycle: the public, exhausted by fifteen years of consumer price inflation, irritated by McNamara’s efficiency and management reforms, and increasingly discomforted by the high toll of SATPO’s counter-insurgency operations in Northwest Montana, had flocked to the Traficant campaign. The final nail in the Haig campaign’s coffin came in early September, when Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa (a man whose impeccable political instincts would lead in the late 90s to his briefly becoming the richest man in the world) tacitly agreed to assist the Traficant campaign with messaging and vote harvesting: trucks bearing pro-Traficant messaging became a feature of the last two months of the election.

In desperation, the Haig camp turned to Mondale to cancel the election: Mondale, increasingly embarrassed by the whole affair, and not desiring to burn the SUP’s remaining goodwill to rescue a man not entirely liked by the party from a mess of his own making just to prevent the election of a congressman who, his reformist sympathies notwithstanding, remained a member of the SUP on paper, refused point-blank. Haig would have to hope that residual sympathy for the SUP as the natural governing party of the CSA would be sufficient to see him through.

The night of 9 November 1993 was far worse than the SUP had feared: as the results began to trickle in, it was clear almost immediately that Haig would come in a distant third to Traficant and Duke. While Traficant was the clear winner of the election, his inability to win a majority of the vote meant that a second round of voting (excluding Haig, Glenn and Kirkland) would be held in two weeks.

In the sole debate between Traficant and Duke (initially intended to be a Haig-Duke affair), Duke played his part to perfection: his bizarre and incoherent performance, suggesting the annexation of the Pacific States of America and New England and alleging that the Traficant campaign was funded by the Rothschild banking family, pushed virtually every undecided voter into the Traficant camp. The election of 23 November 1993 was a foregone conclusion, with the first directly-elected Chairman of the CSA giving a victory speech in the early hours of 24 November promising a radical new direction for the country. Barring miracles, Haig’s political career was over.

In the end, it was a stubborn current account deficit, more than anything else, which killed the Combined Syndicates of America.

The CSA had attained the relative height of its prosperity following the end of the Second Weltkrieg: its Civil-War damaged industry largely reconstructed by the time Russian and Anglo-French soldiers were shaking hands across the Rhine in 1949, it was in a superb position, as the only large-scale industrial economy not essentially reduced to rubble, to become the world’s industrial powerhouse, while its decidedly unideological willingness to trade with anyone who could put up the money ensured that it retained this position well into the 60s. By the early 70s, however, the rest of the world was beginning to catch up: the Japanese-dominated Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere’s escalating industrialisation and Western Europe’s continuing recovery meant that the CSA no longer enjoyed the position that it once did.

A series of commodity shocks in the early 80s, for which the CSA’s key industries (by this point deeply complacent, starved of any real internal development over the preceding twenty years and coasting on thirty-year-old market dominance) were entirely unprepared, exacerbated the situation: when Robert McNamara was installed as Chairman in 1985, he was faced by increasing inflation, a stagnant industrial sector and a pool of reserve capital which had been whittled down alarmingly in recent years.

McNamara’s efforts to right the ship of American Syndicalism were three-pronged: firstly, at the urging of cyberneticist Anthony Stafford Beer, all enterprises above a certain size would be linked to a proposed distributed decision-making network, vastly increasing the economy’s ability to react to sudden changes in incentives; secondly, industrial management techniques originating outside the CSA would be incorporated into the CSA’s industrial sector; and finally, “syndicalist democracy” would be reintroduced on a limited scale for the first time since the early 1940s.

The first prong, resulting in the creation of CYBERSYN, proved of limited use due to the project’s technological limitations, and was largely defunded by the early 90s. The second prong, far more wide-ranging in its impact, was something of a success: the importation of just-in-time manufacturing techniques from Japan, and the introduction of the home-grown Six Sigma process improvement programme across a swathe of industries, helped the CSA regain some of the competitive edge that it had lost during its two decades of complacency (although these roll-outs sparked labour tensions – by 1990, the average worker in the CSA increasingly identified the Syndicalist Union Party’s higher-ups with those pencil-necked assholes in suits who timed your bathroom breaks.)

The third prong, involving the reintroduction of (indirect) elections for Governors of CSRs, had the most intriguing effects. The electoral process established for Gubernatorial elections was enormously convoluted, involving non-secret balloting of workplaces to elect delegates, who in turn elected a candidate (required to be a member of the Syndicalist Union Party in good standing nominated by at least one quarter of his CSR’s delegates to the Chamber of Syndicates and one fifth of his CSR’s union representative) to the office of Governor. This process, clearly intended to ensure that the Governorships remained in the hands of SUP loyalists, nevertheless provided the most accurate gauge of public opinion in the hinterlands for decades. The elections of November 1988, the first under this new system, saw candidates from the reformist wing of the SUP elected everywhere they stood (most notably, Max Baucus, James Stockdale and Dennis Kucinich). While subsequent elections in 1990 and 1992 weren’t quite as comprehensive a victory for any particular faction, it was clear by the time McNamara officially resigned his office in February 1993 that a significant level of factional discontent was bubbling below the serene surface of the SUP’s rule over the CSA.

It was against this backdrop that Alexander Haig ascended to the office of Chairman in 1993: succeeding McNamara largely due to the lack of any obvious alternative, and still somewhat tainted by his close identification with the Northwest Montana Insurgency, he and his inner circle grasped the need to head off any challenge to his rule from within the SUP as soon as possible. The solution that he proposed was a surprisingly radical one. For the first time in fifty years, an open election would be held for the Chairmanship, with Haig running as the Syndicalist Union Party’s candidate: his inevitable and crushing victory over whatever handpicked opponent could be put forward as a plausible opposition standard-bearer, made possible by the SUP’s theoretically absolute control over what electoral infrastructure existed, would hopefully cement his hold on power.

The election, announced in March 1993, was scheduled for November. The process under which it would be conducted was designed to curtail the influence of the reformist faction to the greatest extent possible: in a break with McNamara’s system of “syndicalist democracy”, which would allow reformist Governors to exert pressure on voters in their CSRs, a secret ballot was instituted, with responsibility for tabulating the votes and ensuring the overall integrity of the election falling to a commission headed by the Speaker of the Chamber of Syndicates Walter Mondale (a man of decidedly orthodox Syndicalist views). Furthermore, the ban on parties other than the SUP from standing was lifted.

All that was missing now was an opponent, whom Haig’s connections in the Bureau of Internal Security were happy to provide. For ten years, David Duke had been a prominent and noisy critic of the SUP in the Gulf and Texarkana CSRs, rallying locals against the Chicago government and enjoying close but unspoken ties to “The Ragin’ Cajuns”, a small-scale terrorist group fighting for the creation of an ethnoseparatist Cajun CSR on the model of the New Afrika and Sequoyah CSRs. An astute observer would have noticed that his decade of public fulmination against governmental corruption and treachery had accomplished very little, and that, while many of his associates received significant custodial sentences, nothing particularly bad had happened to him. A very astute observer, willing to tail his car at irregular intervals to an assortment of back-roads in the Mississippi delta, would have – correctly – supposed him to be a long-standing informant for the Bureau of Internal Security. As a foil to Haig, he would be perfect.

Duke’s political grouping, the Popular Democratic Party, was granted certification within days by the CSA’s electoral commission, and provided with some public funding and guaranteed airtime on the CSA’s broadcasting system. As a hedge against the entrance of further candidates into the election, there would be two rounds of voting, the first to ensure that the CSA was forced into a binary choice between Haig and Duke. In comparison to Duke’s noisy entry into the race, the response of the SUP’s nascent reformist caucus was an altogether lower-key affair.

A loose assortment of Governors and Congressmen, brought together at first by their response to the Plains Massacre, had been holding regular discussions since late 1992: in response to Haig’s announcement, they agreed between themselves that one of their number should run for the post of Chairman. It was decided that this responsibility should ultimately fall to Congressman James Traficant, a locally-popular representative of broadly reformist sympathies. His nomination papers, signed by Governors Stockdale, Baucus and Kucinich, were received by the electoral commission in early April 1993, with his candidature being approved shortly afterwards: the SUP, untroubled by the addition of a minor politician to the list of candidates for Chairman, granted him funds and airtime without demur.

Forced into the unfamiliar environment of an election campaign, and unsure about the precise extent of their general popularity, the SUP was nevertheless initially sanguine about their prospects of victory: with polling suggesting that about 70% of the population wanted the reformist caucus to cooperate with the SUP rather than seize control over its apparatus, the Haig camp was more worried about what an overly decisive victory in the first round of voting would do to party unity than they were about the possibility of an unexpectedly close contest. That Haig had badly misread the public mood became clear in early July, when a series of internal polls suggested that Traficant had replaced Duke as Haig’s key opponent, and was within touching distance of first place.

The reaction by the SUP’s official campaign was one of blind panic. Traficant’s scheduled airtime and funding was abruptly pulled, with the electoral commission citing “financial discrepancies”; candidate nominations were reopened, with the previously apolitical John Glenn (pilot on the first manned spaceflight) and Lane Kirkland (head of the AFL, by now much diminished from its "One Big Union" days during Foster's chairmanship of the CSA) entering the election as fellow independents and immediately receiving sustained airtime; and a series of attack adverts against Traficant, alleging large-scale corruption, alcoholism and multiple marital infidelities, were launched by the SUP.

These interventions had little impact by this point in the electoral cycle: the public, exhausted by fifteen years of consumer price inflation, irritated by McNamara’s efficiency and management reforms, and increasingly discomforted by the high toll of SATPO’s counter-insurgency operations in Northwest Montana, had flocked to the Traficant campaign. The final nail in the Haig campaign’s coffin came in early September, when Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa (a man whose impeccable political instincts would lead in the late 90s to his briefly becoming the richest man in the world) tacitly agreed to assist the Traficant campaign with messaging and vote harvesting: trucks bearing pro-Traficant messaging became a feature of the last two months of the election.

In desperation, the Haig camp turned to Mondale to cancel the election: Mondale, increasingly embarrassed by the whole affair, and not desiring to burn the SUP’s remaining goodwill to rescue a man not entirely liked by the party from a mess of his own making just to prevent the election of a congressman who, his reformist sympathies notwithstanding, remained a member of the SUP on paper, refused point-blank. Haig would have to hope that residual sympathy for the SUP as the natural governing party of the CSA would be sufficient to see him through.

The night of 9 November 1993 was far worse than the SUP had feared: as the results began to trickle in, it was clear almost immediately that Haig would come in a distant third to Traficant and Duke. While Traficant was the clear winner of the election, his inability to win a majority of the vote meant that a second round of voting (excluding Haig, Glenn and Kirkland) would be held in two weeks.

In the sole debate between Traficant and Duke (initially intended to be a Haig-Duke affair), Duke played his part to perfection: his bizarre and incoherent performance, suggesting the annexation of the Pacific States of America and New England and alleging that the Traficant campaign was funded by the Rothschild banking family, pushed virtually every undecided voter into the Traficant camp. The election of 23 November 1993 was a foregone conclusion, with the first directly-elected Chairman of the CSA giving a victory speech in the early hours of 24 November promising a radical new direction for the country. Barring miracles, Haig’s political career was over.

Last edited:

Love how Duke is pathetic controlled opposition instead of a significant far-right candidate

Let's see how the breakdown of the CSA goes. Some of the late Soviet controlled opposition turned out to be pretty dangerous when they broke free of their controls.

Interesting to see which CSRs Haig won. There's the Heartland (which we know as a modern-day bastion of Syndicalism), the Black Belt (scared of Duke? Also probably sees a lot of benefit from CSA anti-racism and redistribution), and West Texas, which might be pretty similar to the Black Belt on a racial level even without the bracero program? Could also be military spending or unionized oil workers or who knows what.

Theorie des Partisanen (1993-4)

Theorie des Partisanen (1993-4)

The most immediate consequences of the November 1993 election in Northwest Montana were felt by SATPO: with their greatest patron fallen from grace seemingly forever, such lingering institutional support that they still enjoyed had effectively been cut off. The radically new approach promised by Traficant’s victory speech would presumably include a shakeup of Operation Mountain Lion: all Kanne, North, McChrystal and Brennan could do was wait for further instructions, all the while continuing to cede ground to the insurgent groupings now operating throughout their territory.

Haig’s defeat had emboldened his opponents in the military as well as the political sphere. For the past four years, criticism of the way Operation Mountain Lion was being conducted had been understandably muted by the fact that its largest supporter would almost certainly be the next Chairman after McNamara (only really surfacing in the months following the Plains Massacre). Now, with Haig’s star fading, his opponents within the CSA’s military high command scented a long overdue opportunity to stick the knife in. Even after the embarrassment of the election, Haig retained too much of a power base within the military for open hostility (at least for the time being): from December 1993 onwards, Kanne would bear the brunt of an escalating series of attacks on his leadership (and that of Haig by proxy).

The first sign of this orchestrated campaign was the reprint and subsequent circulation of an extended article on the principles of counter-insurgent warfare written in 1980 by William S. Lind, an academic who had spent the 80s on intermittent secondment to the Army of the CSA. “The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation” was, on one level, simply a restatement of the theories on the nature of conflict with non-state actors set out in former Reichskanzler Carl Schmitt’s famous 1963 lecture, “The Case of the Partisan”; on another, it was almost eerily predictive of Operation Mountain Lion’s initial success and subsequent protracted failure.

The thesis of Lind’s essay can be summarised as follows. Since the widespread adoption of gunpower, conflicts had progressively taken on the following forms: first generation warfare, defined by tactics of line and column and reliant on the musket; then second generation warfare, defined by fire and manoeuvre warfare supported by artillery; then third generation warfare, characterised by officer initiative, speed and infiltration and exemplified by Nestor Makhno’s wildly successful tank warfare in the first two years of the Second Weltkrieg; and finally fourth generation warfare, an inherently asymmetrical affair fought between state military forces and various non-state insurgent forces where the goal of the latter was simply making a continued counter-insurgency too expensive and unpleasant an affair to be maintained.

Counter-insurgency operations conducted on principles drawn from second and third generation warfare would find their effectiveness severely limited against a determined group of non-state actors: reliant for logistical and operational support on a handful of systems which could be progressively overwhelmed by partisans, and with any political support sapped slightly by each civilian death, they were unlikely to attain a lasting victory. In place of these operations, Lind proposed a much smaller commitment of light infantry on the model of Rogers’ Rangers, the 18th-century New Hampshire-based light infantry force which had fought to such effect in the French and Indian War: able to virtually live off the land and no longer dependent on long and unreliable logistical supply chains, they would function almost as a separate insurgent group, looking to win over insurgent-supporting stakeholders rather than directly fighting insurgent networks. Judged by the criteria set out in the essay, it was clear that Operation Mountain Lion had been misconceived from beginning to end.

As well as a clear shot across Haig’s bows, the resurrection of an essay which had languished out of print for more than a decade was a sign that Lind’s most committed patron’s star was rising as rapidly as Kanne’s was falling. Like Kanne, Andrew Bacevich had attended West Point in the late 1960s. Unlike Kanne, his subsequent military career had been one of frustration rather than continued ascent. Lacking the connections necessary to advance to flag rank, he had seen his career stall from 1985 onwards: absent a remarkable change in circumstances, he would retire as a colonel. His work in the immediate aftermath of the Plains Massacre had brought him to the attention of Haig’s opponents within the Army of the CSA: now, with a new approach to the Northwest Montana Insurgency demanded by the CSA’s political leadership, his name was put forward as the overall commander of a smaller force largely prepared on the lines proposed by Lind and intended to function as a replacement for SATPO. Granted an acting promotion to brigadier-general in January 1994, he was immediately commissioned with assembling two brigades of light infantry from regular troops pulled back from the ongoing Centroamerican War. Although Haig was unable to halt the creation of this formation (tentatively named the “SATPO Relief Force”), he was able to use his remaining connections to ensure that no order for the replacement of SATPO would be forthcoming – for the first two months of 1994, the Relief Force would be stuck in a sort of limbo, confined to a base eighty miles outside Chicago.

As this bureaucratic tug-of-war unfolded, the winter of 1993-94, which had started badly for SATPO, was becoming a nightmare. January and early February 1994 saw the coldest temperatures recorded since the 1920s in Northwest Montana: the area’s military and civilian logistical networks, already strained by the steady escalation of insurgent activity, broke altogether under this additional stress. In the handful of areas still under the uninterrupted de facto control of SATPO (by this point, limited to the immediate surroundings of Missoula and Butte and the AFBs used by SATPO’s airborne divisions), some semblance of normal function could be maintained, at the cost of harsher and harsher rationing of food and fuel. Elsewhere, the population was largely left to fend for itself.

The “civilian facilities” which had been established in the first year of Operation Mountain Lion were worst affected. Their population of “pacified” locals and imported Appalachians, forced to live in half-finished “temporary accommodation” for more than three years and treated as virtual prisoners, were forced to burn what fuel they could find to survive. In more than one case, carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty makeshift wood-burning stove killed an entire family; others, running out of wood, simply froze to death. Sporadic evacuations (disrupted to the greatest extent possible by the NWF) managed to head off the worst of the humanitarian crisis: by early February, all of the civilian facilities had been abandoned apart from Dillon, by now converted into a refugee camp for “sensitive persons” (the official euphemism for people highly likely to be killed by the insurgents in the event of capture).

Outside these facilities, the civilian population of Northwest Montana was faced with a choice between freezing and accepting the protection of the NWF. They almost invariably chose the latter option: indeed, it is arguable that the insurgents managed to gain more territory with firewood than they ever had with bullets. By the middle of February 1994, the shift away from SATPO which had begun in early 1993 was complete: everywhere outside the major cities and their bases, SATPO had been driven out of Northwest Montana.

It was against this backdrop that a slight and unexpected thaw in the weather allowed Kanne a rare visit to one of SATPO’s AFBs in late February 1994. Even at this late stage in Operation Mountain Lion, Kanne was still hopeful that the situation could be retrieved: it was entirely possible that the NWF would be overstretched by their territorial gains over the last six months, or that they and the Reconstituted Nauvoo Legion might be induced somehow to turn on each other. Arriving by road to Aalto AFB outside Anaconda in the morning of 27 February 1994, Kanne, accompanied by two junior staffers and Alex Avezado Souza (a photojournalist from the Brazilian Workers’ Republic embedded with SATPO) set about a brief and fairly informal inspection of the base, disregarding the intermittent and inaccurate shelling of the perimeter of the base by a NWF mortar team. The official portion of his visit concluded, he turned to talk to an enlisted man he recognised (Kanne, generally popular with the regulars under his command, surprised him by recalling his name and a similar conversation held three years ago) before posing by a partially dismantled helicopter at Souza’s instructions.

The resulting picture (developed from a badly-damaged negative) was the last of Kanne’s career. Five seconds after it had been taken, an absurdly lucky shot by the mortar team, significantly outside its intended target area, hit the helicopter: Kanne, Souza and four mechanics were killed instantly. To all intents and purposes, SATPO died along with Kanne.

The most immediate consequences of the November 1993 election in Northwest Montana were felt by SATPO: with their greatest patron fallen from grace seemingly forever, such lingering institutional support that they still enjoyed had effectively been cut off. The radically new approach promised by Traficant’s victory speech would presumably include a shakeup of Operation Mountain Lion: all Kanne, North, McChrystal and Brennan could do was wait for further instructions, all the while continuing to cede ground to the insurgent groupings now operating throughout their territory.

Haig’s defeat had emboldened his opponents in the military as well as the political sphere. For the past four years, criticism of the way Operation Mountain Lion was being conducted had been understandably muted by the fact that its largest supporter would almost certainly be the next Chairman after McNamara (only really surfacing in the months following the Plains Massacre). Now, with Haig’s star fading, his opponents within the CSA’s military high command scented a long overdue opportunity to stick the knife in. Even after the embarrassment of the election, Haig retained too much of a power base within the military for open hostility (at least for the time being): from December 1993 onwards, Kanne would bear the brunt of an escalating series of attacks on his leadership (and that of Haig by proxy).

The first sign of this orchestrated campaign was the reprint and subsequent circulation of an extended article on the principles of counter-insurgent warfare written in 1980 by William S. Lind, an academic who had spent the 80s on intermittent secondment to the Army of the CSA. “The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation” was, on one level, simply a restatement of the theories on the nature of conflict with non-state actors set out in former Reichskanzler Carl Schmitt’s famous 1963 lecture, “The Case of the Partisan”; on another, it was almost eerily predictive of Operation Mountain Lion’s initial success and subsequent protracted failure.

The thesis of Lind’s essay can be summarised as follows. Since the widespread adoption of gunpower, conflicts had progressively taken on the following forms: first generation warfare, defined by tactics of line and column and reliant on the musket; then second generation warfare, defined by fire and manoeuvre warfare supported by artillery; then third generation warfare, characterised by officer initiative, speed and infiltration and exemplified by Nestor Makhno’s wildly successful tank warfare in the first two years of the Second Weltkrieg; and finally fourth generation warfare, an inherently asymmetrical affair fought between state military forces and various non-state insurgent forces where the goal of the latter was simply making a continued counter-insurgency too expensive and unpleasant an affair to be maintained.

Counter-insurgency operations conducted on principles drawn from second and third generation warfare would find their effectiveness severely limited against a determined group of non-state actors: reliant for logistical and operational support on a handful of systems which could be progressively overwhelmed by partisans, and with any political support sapped slightly by each civilian death, they were unlikely to attain a lasting victory. In place of these operations, Lind proposed a much smaller commitment of light infantry on the model of Rogers’ Rangers, the 18th-century New Hampshire-based light infantry force which had fought to such effect in the French and Indian War: able to virtually live off the land and no longer dependent on long and unreliable logistical supply chains, they would function almost as a separate insurgent group, looking to win over insurgent-supporting stakeholders rather than directly fighting insurgent networks. Judged by the criteria set out in the essay, it was clear that Operation Mountain Lion had been misconceived from beginning to end.

As well as a clear shot across Haig’s bows, the resurrection of an essay which had languished out of print for more than a decade was a sign that Lind’s most committed patron’s star was rising as rapidly as Kanne’s was falling. Like Kanne, Andrew Bacevich had attended West Point in the late 1960s. Unlike Kanne, his subsequent military career had been one of frustration rather than continued ascent. Lacking the connections necessary to advance to flag rank, he had seen his career stall from 1985 onwards: absent a remarkable change in circumstances, he would retire as a colonel. His work in the immediate aftermath of the Plains Massacre had brought him to the attention of Haig’s opponents within the Army of the CSA: now, with a new approach to the Northwest Montana Insurgency demanded by the CSA’s political leadership, his name was put forward as the overall commander of a smaller force largely prepared on the lines proposed by Lind and intended to function as a replacement for SATPO. Granted an acting promotion to brigadier-general in January 1994, he was immediately commissioned with assembling two brigades of light infantry from regular troops pulled back from the ongoing Centroamerican War. Although Haig was unable to halt the creation of this formation (tentatively named the “SATPO Relief Force”), he was able to use his remaining connections to ensure that no order for the replacement of SATPO would be forthcoming – for the first two months of 1994, the Relief Force would be stuck in a sort of limbo, confined to a base eighty miles outside Chicago.

As this bureaucratic tug-of-war unfolded, the winter of 1993-94, which had started badly for SATPO, was becoming a nightmare. January and early February 1994 saw the coldest temperatures recorded since the 1920s in Northwest Montana: the area’s military and civilian logistical networks, already strained by the steady escalation of insurgent activity, broke altogether under this additional stress. In the handful of areas still under the uninterrupted de facto control of SATPO (by this point, limited to the immediate surroundings of Missoula and Butte and the AFBs used by SATPO’s airborne divisions), some semblance of normal function could be maintained, at the cost of harsher and harsher rationing of food and fuel. Elsewhere, the population was largely left to fend for itself.

The “civilian facilities” which had been established in the first year of Operation Mountain Lion were worst affected. Their population of “pacified” locals and imported Appalachians, forced to live in half-finished “temporary accommodation” for more than three years and treated as virtual prisoners, were forced to burn what fuel they could find to survive. In more than one case, carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty makeshift wood-burning stove killed an entire family; others, running out of wood, simply froze to death. Sporadic evacuations (disrupted to the greatest extent possible by the NWF) managed to head off the worst of the humanitarian crisis: by early February, all of the civilian facilities had been abandoned apart from Dillon, by now converted into a refugee camp for “sensitive persons” (the official euphemism for people highly likely to be killed by the insurgents in the event of capture).

Outside these facilities, the civilian population of Northwest Montana was faced with a choice between freezing and accepting the protection of the NWF. They almost invariably chose the latter option: indeed, it is arguable that the insurgents managed to gain more territory with firewood than they ever had with bullets. By the middle of February 1994, the shift away from SATPO which had begun in early 1993 was complete: everywhere outside the major cities and their bases, SATPO had been driven out of Northwest Montana.

It was against this backdrop that a slight and unexpected thaw in the weather allowed Kanne a rare visit to one of SATPO’s AFBs in late February 1994. Even at this late stage in Operation Mountain Lion, Kanne was still hopeful that the situation could be retrieved: it was entirely possible that the NWF would be overstretched by their territorial gains over the last six months, or that they and the Reconstituted Nauvoo Legion might be induced somehow to turn on each other. Arriving by road to Aalto AFB outside Anaconda in the morning of 27 February 1994, Kanne, accompanied by two junior staffers and Alex Avezado Souza (a photojournalist from the Brazilian Workers’ Republic embedded with SATPO) set about a brief and fairly informal inspection of the base, disregarding the intermittent and inaccurate shelling of the perimeter of the base by a NWF mortar team. The official portion of his visit concluded, he turned to talk to an enlisted man he recognised (Kanne, generally popular with the regulars under his command, surprised him by recalling his name and a similar conversation held three years ago) before posing by a partially dismantled helicopter at Souza’s instructions.

The resulting picture (developed from a badly-damaged negative) was the last of Kanne’s career. Five seconds after it had been taken, an absurdly lucky shot by the mortar team, significantly outside its intended target area, hit the helicopter: Kanne, Souza and four mechanics were killed instantly. To all intents and purposes, SATPO died along with Kanne.

William S. Lind

His career in the CSA must have been fascinating because either he's gone a complete mental shift or he's been keeping very, very quiet about his beliefs.

It's surprising what you can get away with believing in private if you keep your head down and concentrate on abtruse questions of operational strategy rather than anything political.His career in the CSA must have been fascinating because either he's gone a complete mental shift or he's been keeping very, very quiet about his beliefs.

He got very far OTL! He was an aide to Gary Hart OTL, after all...His career in the CSA must have been fascinating because either he's gone a complete mental shift or he's been keeping very, very quiet about his beliefs.

Threadmarks

View all 49 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Five Days in May (1994) Part III: Suffering Shipwreck with Dignity Five Days in May (1994); Part IV - the Battle of Chicago Infobox: the May Crisis Creating a Reality for Ourselves where the Bleeding is (1994) Go, Ghost, Go (1994) Map: Northwest Montana during the Siege of Butte (1994) maybe SOMEONE will be able to see SOMETHING as it really is WATCHOUT (1994-5) The Sinews of Peace (1995-1997)

Share: