Part 7

The Belgian Revolution was a conflict which was an attempt at the secession of the southern provinces from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium. Although 62% of the population lived in the South, they were assigned the same number of representatives in the States General. At the most basic level, the North was for free trade, while less-developed local industries in the South called for the protection of tariffs. Free trade lowered the price of bread, made from wheat imported through the reviving port of Antwerp; at the same time, these imports from the Baltic depressed agriculture in Southern grain-growing regions.

The more numerous Northern provinces represented a majority in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands' elected Lower Assembly, and therefore the more populous Southerners felt significantly under-represented. King William I was from the North, lived in the present day Netherlands, and largely ignored the demands for greater autonomy. His more progressive and amiable representative living in Brussels, which was the twin capital, was the Crown-Prince William, later King William II, who had some popularity among the upper class but none among peasants and workers.

A linguistic reform in 1823 was intended to make Dutch the official language in the Flemish provinces, since it was the language of most of the Flemish population. This reform met with strong opposition from the upper and middle classes who at the time were mostly French-speaking. On 4 June 1830, this reform was abolished. Faith was another cause of the Belgian Revolution. In the politics of the south Roman Catholicism was the important factor. Its partisans fought against the freedom of religion proclaimed by William.

On 25 August 1830 rioters swiftly took possession of government buildings in Brussels and began a general independence struggle. Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force.

To make up for the small size of the domestic Dutch forces, King William had already taken steps to create a military force out of the manpower reserves presented by the the South African Confederation, which represented at the time nearly 40% of Dutch speaking Protestants within the Kingdom and would thus hold sympathies with the cause against the dissenting Catholics.

On the 23rd of September, more than 14 000 Dutch troops (of which 6 000 were an all-volunteer force from the SAC) marched into Brussels in order to end the revolution and arrest its leaders. After 2 days of bloody street fighting the government buildings were retaken and the revolution effectively put down through force. The Great Powers had looked on with concern that this would cause an international crisis but the quick and heavy hand of the Dutch dispelled these fears. Some patriots were marked as too dangerous to be allowed to walk the streets of Brussels and were imprisoned. Many tens of thousands more fearing treason trials fled to France or to the SAC. Once reaching Kaapstad, many would attempt to make the most of their circumstance and eventually travel to the Orange River or the Witwatersrand in search of their fortune.

In the late 1830s diamonds were discovered in the Orange River which separated the Cape region of the colony from the further interior. At the initial stage of the rush, a slow trickle of prospectors descended onto the bank of the Orange river and by the end of 1840, several thousand people were encamped along the bank. The success of the first systematic diamond exploration on the north bank of the Orange encouraged more adventurers to invest time and savings while the rush lasted.

The interior had long been a source of a trickle of gold since the 17th century, but in a region known as the Witwatersrand a discovery of an outcrop of a massive gold vein on the farm Langlaagte in February 1840 was made. Further excavation revealed the region to possibly be the largest deposit of gold on the planet. Diggers eagerly came by carriage, by horse or by foot from all over the SAC and abroad to try their luck and strike it rich.

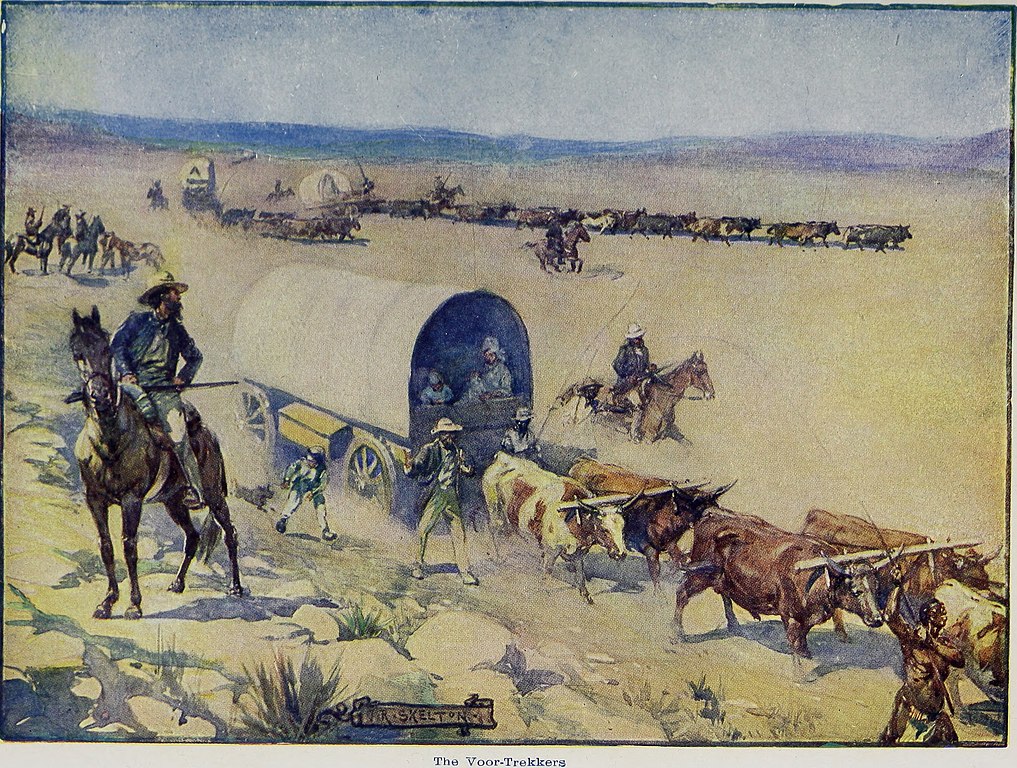

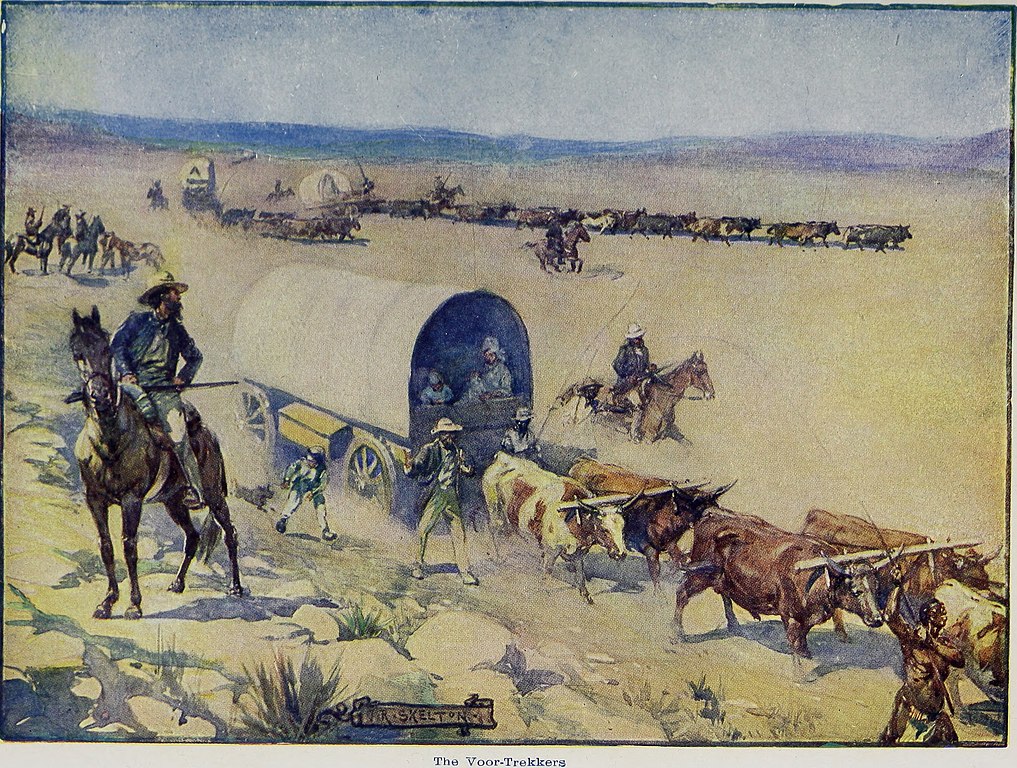

Between the years 1840 and 1860 it was recorded that nearly 400 000 people immigrated to the SAC, equally Dutch and German, but also French, British, American and Russian. The effects of the rush were substantial. Population pressures pushed the frontiersmen, who were still colloquilly known as the Boers, further into the fertile highlands beyond the Limpopo river, which was later to be named “Wilhelmina”. The Witwatersrand grew from a small settlement area of about 3 000 people in 1836 into a massive city by the name of Willemstad with a population of more than 100 000 by 1860; surpassing even the population of the very first city that had been founded in Southern Africa, Kaapstad, at the time. Roads, churches, schools and other towns were built throughout the interior to accommodate the wave of new residents, prospectors and goods-peddlers that saw the opportunity for business.

The vast amount of capital injection into an economy that had been predominantly agricultural based transformed South African society and truly propelled the colony into the modern era. The first railway line had only been built in the Belgian region of the UKN in 1835, but as a result of the rapid development of the goldfields on the Witwatersrand in the 1840s the Netherlands-South African Railway Company was founded and commissioned on 20 July 1843 to construct a railway line from Willemstad to Kaapstad. The line was opened on 17 March 1846. Coal deposits discovered just some distance East of the Witwatersrand enabled the easy supply of power for the locomotives that streamed up and down the Veld.

However, a closer port for the export of precious metals and minerals was decided to be more practically located at Lydsaamheid. In 1840, the town was described as a poor place, with narrow streets, fairly good flat-roofed houses, grass huts, decayed forts, and a rusty cannon, enclosed by a recently erected wall 1.8 metes (6 ft) high and protected by bastions at intervals. The growing importance of the goldfields led, however, to greater interest being taken in the development of a proper port. A commission was sent by the SAC government in 1845 to drain the marshy land near the settlement, to plant the blue gum tree, and to build a hospital and a church. In 1854 the NZASM constructed the railway line leading from Vereeniging to Lydsaamheid.

The colony and thus the Kingdom of the Netherlands was by this point the largest producer of gold and diamonds in the world. With the extreme amount of wealth pouring into the treasury the UKN was experiencing a type of economic injection and revitalization not felt for centuries. After Britain the UKN was the first nation to truly follow the trend of industrialization. Its close proximity to Britain and its strong trading relation with her allowed new technologies to subsequently arrive in the Kingdom. In addition, the UKN had a large reserve of iron and coal, which were vital resources for industrialization and multiple rivers served as highways for goods which became an important part of transportation and distribution. With skills, geographical position, and resources, it became evident that the UKN possessed the pre-requisites to follow the steps of Britain, thus, bringing the industrial revolution to mainland Europe.

New textile mills were built in North Brabant and in the region of Twente. Amsterdam harbour was linked directly to the North Sea by means of a new canal. For its part Rotterdam received the so-called "Nieuwe Waterweg", enabling it to set up a profitable trading route with the ironworks and collieries in the Ruhrgebiet.

In 1824, Paul Huart Chapel had built an iron smelting plant with 8 blast furnaces. His factory used the new puddling process in producing better quality iron. His plant also utilized coke, which made the iron making process more efficient. With the new iron plants, by 1850, the Kingdom produced around 200,000 tons of iron. Companies like that of Cockerill capitalized on the expansion of railways and began to produce railroad tracks as well as locomotives. Eventually, they began to export it to neighboring countries who wanted their own railroad system. Both Germany and France demanded railroads and ordered it from the UKN. From textile and iron, it developed a capacity to produce steel and to enter in the field of chemical industry. In 1865, steel began to be produced in the industrial center of Liege.

Dutch industrialists, financiers and imperialists started to show greater interest in the prospects of colonisation. The SAC’s vast growth in population and its discovery of such vast resources to many felt like a second divine chance had been given to the Netherlands which had up until that point been a power in decline for more than a century.

Since the establishment of the VOC in the 17th century, the expansion of Dutch territory had been a business matter. Graaf van den Bosch's Governor-generalship in the East Indies confirmed profitability as the foundation of official policy, restricting its attention to Java, Sumatra and Bangka. However, from about 1840, Dutch national expansionism saw them wage a series of wars to enlarge and consolidate their possessions in the outer islands. Motivations included: the protection of areas already held; the intervention of Dutch officials ambitious for glory or promotion; and to establish Dutch claims throughout the archipelago to prevent intervention from other Western powers during the European push for colonial possessions. As exploitation of Indonesian resources expanded off Java, the outer islands came under direct Dutch government control or influence.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the balance of military power shifted towards the industrialising Dutch and against pre-industrial independent indigenous Indonesian polities as the technology gap widened. Military leaders and Dutch politicians believed they had a moral duty to free the native Indonesian peoples from indigenous rulers who were considered oppressive, backward, or disrespectful of international law.

Although Indonesian rebellions broke out, direct colonial rule was extended throughout the rest of the archipelago and control taken from the remaining independent local rulers. Southwestern Sulawesi was occupied, the island of Bali was subjugated with military conquests as were the remaining independent kingdoms in Maluku, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara. Other rulers including the Sultans of Tidore in Maluku, Pontianak, and Palembang in Sumatra, requested Dutch protection from independent neighbours thereby avoiding Dutch military conquest and were able to negotiate better conditions under colonial rule. Eventually the Dutch influence of the East Indies extended to all of Borneo and New Guinea.

Many other Great Powers looked at the sudden increase of Dutch wealth due to a former colonial backwater with great amazement. The untouched resources and markets of Africa and Asia and the worry of lost opportunity encouraged many others to follow the Dutch example in order to emulate their success in Southern Africa and the East Indies.

While tropical Africa was not a large zone of investment at the time, other regions were. The vast interior between Egypt and the gold and diamond-rich southern Africa had strategic value in securing the flow of overseas trade. Britain was under political pressure to secure lucrative markets against encroaching rivals. Thus, it was crucial to secure the key waterway between East and West; the Suez Canal. Many other powers had similar interests to the British or simply saw colonies as sources of international prestige.

******************************

I have no idea how to divide Africa, please help.

The more numerous Northern provinces represented a majority in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands' elected Lower Assembly, and therefore the more populous Southerners felt significantly under-represented. King William I was from the North, lived in the present day Netherlands, and largely ignored the demands for greater autonomy. His more progressive and amiable representative living in Brussels, which was the twin capital, was the Crown-Prince William, later King William II, who had some popularity among the upper class but none among peasants and workers.

A linguistic reform in 1823 was intended to make Dutch the official language in the Flemish provinces, since it was the language of most of the Flemish population. This reform met with strong opposition from the upper and middle classes who at the time were mostly French-speaking. On 4 June 1830, this reform was abolished. Faith was another cause of the Belgian Revolution. In the politics of the south Roman Catholicism was the important factor. Its partisans fought against the freedom of religion proclaimed by William.

On 25 August 1830 rioters swiftly took possession of government buildings in Brussels and began a general independence struggle. Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force.

To make up for the small size of the domestic Dutch forces, King William had already taken steps to create a military force out of the manpower reserves presented by the the South African Confederation, which represented at the time nearly 40% of Dutch speaking Protestants within the Kingdom and would thus hold sympathies with the cause against the dissenting Catholics.

On the 23rd of September, more than 14 000 Dutch troops (of which 6 000 were an all-volunteer force from the SAC) marched into Brussels in order to end the revolution and arrest its leaders. After 2 days of bloody street fighting the government buildings were retaken and the revolution effectively put down through force. The Great Powers had looked on with concern that this would cause an international crisis but the quick and heavy hand of the Dutch dispelled these fears. Some patriots were marked as too dangerous to be allowed to walk the streets of Brussels and were imprisoned. Many tens of thousands more fearing treason trials fled to France or to the SAC. Once reaching Kaapstad, many would attempt to make the most of their circumstance and eventually travel to the Orange River or the Witwatersrand in search of their fortune.

In the late 1830s diamonds were discovered in the Orange River which separated the Cape region of the colony from the further interior. At the initial stage of the rush, a slow trickle of prospectors descended onto the bank of the Orange river and by the end of 1840, several thousand people were encamped along the bank. The success of the first systematic diamond exploration on the north bank of the Orange encouraged more adventurers to invest time and savings while the rush lasted.

The interior had long been a source of a trickle of gold since the 17th century, but in a region known as the Witwatersrand a discovery of an outcrop of a massive gold vein on the farm Langlaagte in February 1840 was made. Further excavation revealed the region to possibly be the largest deposit of gold on the planet. Diggers eagerly came by carriage, by horse or by foot from all over the SAC and abroad to try their luck and strike it rich.

Between the years 1840 and 1860 it was recorded that nearly 400 000 people immigrated to the SAC, equally Dutch and German, but also French, British, American and Russian. The effects of the rush were substantial. Population pressures pushed the frontiersmen, who were still colloquilly known as the Boers, further into the fertile highlands beyond the Limpopo river, which was later to be named “Wilhelmina”. The Witwatersrand grew from a small settlement area of about 3 000 people in 1836 into a massive city by the name of Willemstad with a population of more than 100 000 by 1860; surpassing even the population of the very first city that had been founded in Southern Africa, Kaapstad, at the time. Roads, churches, schools and other towns were built throughout the interior to accommodate the wave of new residents, prospectors and goods-peddlers that saw the opportunity for business.

The vast amount of capital injection into an economy that had been predominantly agricultural based transformed South African society and truly propelled the colony into the modern era. The first railway line had only been built in the Belgian region of the UKN in 1835, but as a result of the rapid development of the goldfields on the Witwatersrand in the 1840s the Netherlands-South African Railway Company was founded and commissioned on 20 July 1843 to construct a railway line from Willemstad to Kaapstad. The line was opened on 17 March 1846. Coal deposits discovered just some distance East of the Witwatersrand enabled the easy supply of power for the locomotives that streamed up and down the Veld.

However, a closer port for the export of precious metals and minerals was decided to be more practically located at Lydsaamheid. In 1840, the town was described as a poor place, with narrow streets, fairly good flat-roofed houses, grass huts, decayed forts, and a rusty cannon, enclosed by a recently erected wall 1.8 metes (6 ft) high and protected by bastions at intervals. The growing importance of the goldfields led, however, to greater interest being taken in the development of a proper port. A commission was sent by the SAC government in 1845 to drain the marshy land near the settlement, to plant the blue gum tree, and to build a hospital and a church. In 1854 the NZASM constructed the railway line leading from Vereeniging to Lydsaamheid.

The colony and thus the Kingdom of the Netherlands was by this point the largest producer of gold and diamonds in the world. With the extreme amount of wealth pouring into the treasury the UKN was experiencing a type of economic injection and revitalization not felt for centuries. After Britain the UKN was the first nation to truly follow the trend of industrialization. Its close proximity to Britain and its strong trading relation with her allowed new technologies to subsequently arrive in the Kingdom. In addition, the UKN had a large reserve of iron and coal, which were vital resources for industrialization and multiple rivers served as highways for goods which became an important part of transportation and distribution. With skills, geographical position, and resources, it became evident that the UKN possessed the pre-requisites to follow the steps of Britain, thus, bringing the industrial revolution to mainland Europe.

New textile mills were built in North Brabant and in the region of Twente. Amsterdam harbour was linked directly to the North Sea by means of a new canal. For its part Rotterdam received the so-called "Nieuwe Waterweg", enabling it to set up a profitable trading route with the ironworks and collieries in the Ruhrgebiet.

In 1824, Paul Huart Chapel had built an iron smelting plant with 8 blast furnaces. His factory used the new puddling process in producing better quality iron. His plant also utilized coke, which made the iron making process more efficient. With the new iron plants, by 1850, the Kingdom produced around 200,000 tons of iron. Companies like that of Cockerill capitalized on the expansion of railways and began to produce railroad tracks as well as locomotives. Eventually, they began to export it to neighboring countries who wanted their own railroad system. Both Germany and France demanded railroads and ordered it from the UKN. From textile and iron, it developed a capacity to produce steel and to enter in the field of chemical industry. In 1865, steel began to be produced in the industrial center of Liege.

Dutch industrialists, financiers and imperialists started to show greater interest in the prospects of colonisation. The SAC’s vast growth in population and its discovery of such vast resources to many felt like a second divine chance had been given to the Netherlands which had up until that point been a power in decline for more than a century.

Since the establishment of the VOC in the 17th century, the expansion of Dutch territory had been a business matter. Graaf van den Bosch's Governor-generalship in the East Indies confirmed profitability as the foundation of official policy, restricting its attention to Java, Sumatra and Bangka. However, from about 1840, Dutch national expansionism saw them wage a series of wars to enlarge and consolidate their possessions in the outer islands. Motivations included: the protection of areas already held; the intervention of Dutch officials ambitious for glory or promotion; and to establish Dutch claims throughout the archipelago to prevent intervention from other Western powers during the European push for colonial possessions. As exploitation of Indonesian resources expanded off Java, the outer islands came under direct Dutch government control or influence.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the balance of military power shifted towards the industrialising Dutch and against pre-industrial independent indigenous Indonesian polities as the technology gap widened. Military leaders and Dutch politicians believed they had a moral duty to free the native Indonesian peoples from indigenous rulers who were considered oppressive, backward, or disrespectful of international law.

Although Indonesian rebellions broke out, direct colonial rule was extended throughout the rest of the archipelago and control taken from the remaining independent local rulers. Southwestern Sulawesi was occupied, the island of Bali was subjugated with military conquests as were the remaining independent kingdoms in Maluku, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara. Other rulers including the Sultans of Tidore in Maluku, Pontianak, and Palembang in Sumatra, requested Dutch protection from independent neighbours thereby avoiding Dutch military conquest and were able to negotiate better conditions under colonial rule. Eventually the Dutch influence of the East Indies extended to all of Borneo and New Guinea.

Many other Great Powers looked at the sudden increase of Dutch wealth due to a former colonial backwater with great amazement. The untouched resources and markets of Africa and Asia and the worry of lost opportunity encouraged many others to follow the Dutch example in order to emulate their success in Southern Africa and the East Indies.

While tropical Africa was not a large zone of investment at the time, other regions were. The vast interior between Egypt and the gold and diamond-rich southern Africa had strategic value in securing the flow of overseas trade. Britain was under political pressure to secure lucrative markets against encroaching rivals. Thus, it was crucial to secure the key waterway between East and West; the Suez Canal. Many other powers had similar interests to the British or simply saw colonies as sources of international prestige.

******************************

I have no idea how to divide Africa, please help.

Last edited: