Wow, there is some homages to my idea there in that update (and oh, your long update! I hope the next one is also as long as that!). I am happy! Looking forward to my idea's adapatation into the TL for the first time!

Honorius was swift to agree - legitimizing the Portuguese conquests in Morocco,

Corrections:

It was at this point that Ivan reached out to Waldemar, offering to split Poland and Lithuania between them and offering Samogatia to the Teutonic Order as a further inducement. Waldemar would leap at this suggestion, signing the Treaty of Thorn in April of 1426 and allying the Muscovite and Nordic forces against the Jagellions and Zygimantis. The Teutonic forces in Livonia moved swiftly to assert their power in Samogatia, taking control of the region by the end of 1426 (14). This intervention led to a collapse of Zygimantis' positions and his death in the Battle of Szawle when he marched north to oppose the Teutonic invasion. The Jagellions were quick to muster support from the Old Lithuanian nobility, who were willing to accept Jogaila's sons as rulers given the other options available. By early 1427 Švitrigaila's position had become untenable and he fled eastward to the court of his one-time ally and founder of the Nogai Horde Edigu's son Sheidak Nogai Khan who had taken up rule in the eastern parts of the Golden Horde in which his family had control during the years of the Golden Horde's civil war (15).

Casimir IV Jagellion meets his betrothed at Warsawa

While Ivan advanced towards Vilnius and the Livonian forces moved through Samogatia, the Jagellions moved rapidly to oppose them. Intense fighting around Krewo, Zaslaw and Minsk saw Ivan driven to a standstill, pushing him southward towards Rohaczew. The Livonian advance found itself blunted at Kowno, but left most of Samogatia in Livonian hands. Ivan would launch an invasion into southern Lithuania, hoping to grasp hold of Kiev and establish a claim to the ancient Rus. In the meanwhile, Waldemar and his Teutonic allies began a series of attacks into the eastern reaches of Mazowia, resulting in fierce battles around Wizna and Lomza which turned in favor of Waldemar. By mid-1427 the war had shifted to the lands around Kiev, where Ivan was undertaking a major advance in the face of serious opposition. In battles at Rylsk, Putwyl and Baturyn, the Muscovite advance stove in the Jagellion front, forcing the redeployment of large forces from Poland and Old Lithuania to counter the assault. The Battles of Czemihow and Ostrz ended in Muscovite victories, but on the outskirts of Kiev the Lithuanians were finally able to muster enough forces to end the advance. The Battle of Kiev saw immense numbers of soldiers clash in fierce melees, eventually turning in Jagellion favor after taking large losses, including several prominent nobles. By the waning days of 1427 the Muscovite advance had come to an end, and would gradually contract back to Putwyl (16).

After almost a decade of intense conflict, the two sides began sending out peace feelers. King Waldemar would be the first to do so, worried about his father's worsening health and hopeful that he could leave his brother - the Grandmaster of the Teutonic Order (17) - in charge of his Polish conquests, initiating the negotiations which would be undertaken at Warsawa. Ivan joined soon after, dispatching a close advisor to serve as proxy. Over the course of 1428 the two sides undertook intense negotiations, while skirmishes and raids continued on all fronts, eventually coming to an agreement in the Peace of Warsawa. Waldemar would renounce his claim to the Kingdom of Poland in return for the Provinces of Greater Poland and Mazowia as well as acknowledging the legality of the transfer of Samogatia to the Teutonic Order. Ivan of Moscow agreed to give up his claim to the Grand Principality of Lithuania in return for his conquests starting in the north on the Daugava River, running through Polotsk, Vitebsk, Smolensk, Roslaw, Briansk, Trubczewsk, Putwyl and Poltawa in the south. This vast swathe of land was given over to Ivan while his daughter Anastacia married the young Casimir IV Jagellion while Eleanor of Malmö was married to Ivan's heir Vasily Ivanovich. Thus the Great Eastern War came to an end, known to history as the Polish-Lithuanian Succession War (18). In time Alexander Jagellion would take up regency of Lithuania for his brother, ruling from Kiev. The loss of Mazowia came as a deep blow to the Piast rulers of the region, who were forced to move southward and settled around the Kievan lands, gaining large tracts of land in the region in an effort to impose a feudal system on the otherwise lawless region (19).

(14) The Treaty of Thorn begin an alliance between Muscovy and the Nordic Kingdoms which allows the Muscovites to begin participating in wider European politics and will prove useful in the future. The invasion of Samogatia would have experienced far more popular uprising than do occur, if not for the immense losses taken by the Samogatian nobility in the war so far.

Okay. I have to note that normally we would have to call them Samogitia. Not Samogatia, and normally since Samogitia region is generally depicted as "Samogitia" in this TL, i would like this to match with the past updates. Located in the previous update (Update Forty-Seven). Hopefully, it would look like this:

It was at this point that Ivan reached out to Waldemar, offering to split Poland and Lithuania between them and offering Samogitia to the Teutonic Order as a further inducement. Waldemar would leap at this suggestion, signing the Treaty of Thorn in April of 1426 and allying the Muscovite and Nordic forces against the Jagellions and Zygimantis. The Teutonic forces in Livonia moved swiftly to assert their power in Samogitia, taking control of the region by the end of 1426 (14). This intervention led to a collapse of Zygimantis' positions and his death in the Battle of Szawle when he marched north to oppose the Teutonic invasion. The Jagellions were quick to muster support from the Old Lithuanian nobility, who were willing to accept Jogaila's sons as rulers given the other options available. By early 1427 Švitrigaila's position had become untenable and he fled eastward to the court of his one-time ally and founder of the Nogai Horde Edigu's son Sheidak Nogai Khan who had taken up rule in the eastern parts of the Golden Horde in which his family had control during the years of the Golden Horde's civil war (15).

Casimir IV Jagellion meets his betrothed at Warsawa

While Ivan advanced towards Vilnius and the Livonian forces moved through Samogitia, the Jagellions moved rapidly to oppose them. Intense fighting around Krewo, Zaslaw and Minsk saw Ivan driven to a standstill, pushing him southward towards Rohaczew. The Livonian advance found itself blunted at Kowno, but left most of Samogitia in Livonian hands. Ivan would launch an invasion into southern Lithuania, hoping to grasp hold of Kiev and establish a claim to the ancient Rus. In the meanwhile, Waldemar and his Teutonic allies began a series of attacks into the eastern reaches of Mazowia, resulting in fierce battles around Wizna and Lomza which turned in favor of Waldemar. By mid-1427 the war had shifted to the lands around Kiev, where Ivan was undertaking a major advance in the face of serious opposition. In battles at Rylsk, Putwyl and Baturyn, the Muscovite advance stove in the Jagellion front, forcing the redeployment of large forces from Poland and Old Lithuania to counter the assault. The Battles of Czemihow and Ostrz ended in Muscovite victories, but on the outskirts of Kiev the Lithuanians were finally able to muster enough forces to end the advance. The Battle of Kiev saw immense numbers of soldiers clash in fierce melees, eventually turning in Jagellion favor after taking large losses, including several prominent nobles. By the waning days of 1427 the Muscovite advance had come to an end, and would gradually contract back to Putwyl (16).

After almost a decade of intense conflict, the two sides began sending out peace feelers. King Waldemar would be the first to do so, worried about his father's worsening health and hopeful that he could leave his brother - the Grandmaster of the Teutonic Order (17) - in charge of his Polish conquests, initiating the negotiations which would be undertaken at Warsawa. Ivan joined soon after, dispatching a close advisor to serve as proxy. Over the course of 1428 the two sides undertook intense negotiations, while skirmishes and raids continued on all fronts, eventually coming to an agreement in the Peace of Warsawa. Waldemar would renounce his claim to the Kingdom of Poland in return for the Provinces of Greater Poland and Mazowia as well as acknowledging the legality of the transfer of Samogitia to the Teutonic Order. Ivan of Moscow agreed to give up his claim to the Grand Principality of Lithuania in return for his conquests starting in the north on the Daugava River, running through Polotsk, Vitebsk, Smolensk, Roslaw, Briansk, Trubczewsk, Putwyl and Poltawa in the south. This vast swathe of land was given over to Ivan while his daughter Anastacia married the young Casimir IV Jagellion while Eleanor of Malmö was married to Ivan's heir Vasily Ivanovich. Thus the Great Eastern War came to an end, known to history as the Polish-Lithuanian Succession War (18). In time Alexander Jagellion would take up regency of Lithuania for his brother, ruling from Kiev. The loss of Mazowia came as a deep blow to the Piast rulers of the region, who were forced to move southward and settled around the Kievan lands, gaining large tracts of land in the region in an effort to impose a feudal system on the otherwise lawless region (19).

(14) The Treaty of Thorn begin an alliance between Muscovy and the Nordic Kingdoms which allows the Muscovites to begin participating in wider European politics and will prove useful in the future. The invasion of Samogitia would have experienced far more popular uprising than do occur, if not for the immense losses taken by the Samogitian nobility in the war so far.

In update Twenty-Six, there is some inconsistencies, particularly in here:

The Knights appealed to their allies for help, and Sigismund of Hungary, Wenceslaus, King of the Romans, and the Livonian Order promised financial aid and reinforcements.

Change that into "Sigismund of Luxembourg, Holy Roman Emperor". By that event occured ITTL, Sigismund is now Holy Roman Emperor and Wenceslaus is dead by that time. I hope it would look like this in the end:

The Knights appealed to their allies for help, and Sigismund of Hungary, Wenceslaus, King of the Romans, and the Livonian Order promised financial aid and reinforcements.

And the last one is seems to be on the last update.

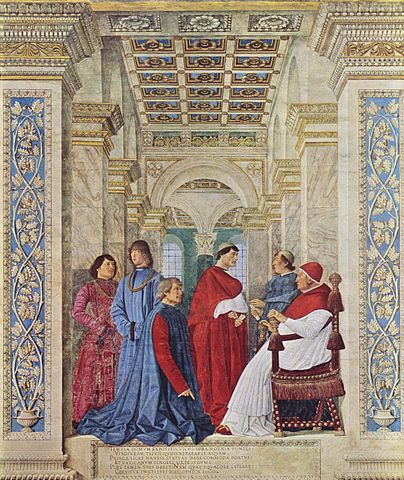

Painting of Pope

Honrius V at the height of his power

Typo. Needs to be changed from "Honrius" to "Honorius".

Now to reply to Emperor Constantine:

Finally, I never heard your opinion on an Abbasid Sultan of Egypt. Looking forward to the next chapter.

@Emperor Constantine here's Zulfurium's opinion on your idea.

I did actually incorporate the Abbasid Caliph. Specifically his daughter married Jahan Shah and as a result the Qara Qoyunlu now claim descent from the Abbasids. Al-Musta'in never attempts his coup, instead he closely supports the Qara Qoyunlu's attempts at establishing their Sultanate and allies with them. The Qara Qoyunlu and Ottomans are probably the most stable of the post-Timurid period, with the Aq Qoyunlu as the most unstable, struggling with the Persian nobility in an effort to establish a proper Persian Shahdom. It bears mentioning that Uzun Hasan will turn up later in the TL and will play a significant role in stabilizing the Aq Qoyunlu.

(There are my ideas i planning for you

@Zulfurium about Luxembourg but now i decided against it, but here's my descriptions of João II of Lancaster (mostly about his family) which would be introduced in the next update.)

João II of Lancaster, during his early years in Portugal, began to be fascinated with the idea of having many children and raising them to become illustrous like João I's children, noticing some of them become very famous. By the time after marrying with Isabella, he become somewhat obsessed with it and turned it into determination by the time on 1414, just before his heir Henrique is born. After he (Henrique) is born he (João II) would have more 11 children with him, which is Maria, Duarte, João, Branca, Fernando, Joana, Isabel, Pedro, Carlota, Iolanda, and Tomás. All of them would be very important to all of Europe, this TL and the world ITTL because of their sheer talents (i will describe them later), and being somewhat unprecedented for a generation. He also has a fictional Portuguese mistress in which he would have 9 children with him though some would die young. They are Catarina, Beatrice, Carlos, Leonor, Filipe, António, Ana, Afonso, and finally Luis. They won't be as prominent as their half-brothers and half-sisters since they are less talented than them, though some of them managed to get as much talents as the Ilustrous Generation of João II (particularly Carlos if you want to know). That was the children of João II of Lancaster!

(Update: toned down the text to be less commanding, added a correction, and also added a promised description of João II).