Update One: A Princely Miracle

Hello everyone!

I have been reading timelines for years, so I thought it was time to start contributing. So without much further ado I would like to present:

In September of 1370 a young boy lay dying of the dread plague which had swept across Europe in a series of deadly waves. Tales of his brave warrior father had always been a source of wonder, comfort and fascination to the young boy, however, that image is but one of many surrounding the man who would in time become known as The Black Prince in a world that would never be. As his son lay dying Edward, Prince of Wales, prepared to leave the smoldering ruins of Limoges behind. The city, which had thrown open its gates to the Duc de Berry, had been properly punished for its inconstancy. Three thousand men, women and children who lived in the city had been given over to his troops, who had sacked the city in a brutal lesson to any who would betray the might of England. The siege and sack had utterly sapped the energy from the sickly prince, who had suffered from amoebic dysentery since his campaigns in Spain in previous years.

Edward of Angoulême, the young boy, took a turn for the worse as his father neared the city of Bordeaux and priests were called to give the boy his last rites. However, at that moment a miracle occurred and the boy stabilized. With his sick and exhausted father and terrified mother at his side the boy slowly recovered from the horrific disease (1). Bells were rung across Bordeaux in celebration of Edward's survival, as the tale of his miraculous recovery spreads and his relieved parents prepare to leave the lands which they had called home for the last many years. By the new year Edward of Angoulême had recovered fully from his sickness and, together with his family, left Aquitaine for England where his grandfather awaited. Left behind to defend the English possessions in France was Edward's uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster alongside Jean III de Grailly, Captal de Buch, one of the greatest military leaders on the English side. Throughout the year, John of Gaunt fought hard to retain what he could of Aquitaine, but he found himself under constant pressure and without proper support. By late 1371 John of Gaunt married Infanta Constance of Castile, claimant to the Castilian throne, thereby securing a claim to Castilian throne and prepared to leave for England.

The Battle of La Rochelle

As the Prince of Wales and his family settled into their home at Wallingford Castle in Berkshire hoping to recover his health, the war in France intensified under the constant French assaults led by the wily Breton Constable of France Bertrand de Guesclin on the lands and territories of England and its allies while the fleets of Castile worked to interdict the English convoys connecting Aquitaine to England. In June 1372 the Castilian Fleet intercepted a English convoy under the command of the Earl of Pembroke near La Rochelle. Over the subsequent two days the English ships carrying enought pay to support 3,000 combatants for a year and reinforcements of horse and men were sunk. This weakened the English forces in Aquitaine significantly, endangered the communications between Bordeaux and England, and opened the path to French raids on England. Edward III set off with a large fleet of impressed merchant ships to beat back the Castilians and open the rout to Bordeaux once more. However, this fleet found itself defeated by contrary winds which blew for weeks on end until it became too late in the year to sail, thereby ending with Edward having to concede before the whims of weather and sea.

The loss of the convoy in June led to a French attempt at taking the port of La Rochelle and its hinterlands. In the subsequent fighting the Captal de Buch and his forces were ambushed at night by a landing party of French forces under the renowned Welsh mercenary and claimant Prince of Wales Owain Lawgoch. In the subsequent fighting the Captal was almost captured, only making his way to safety by fighting on by torchlight and escaping into the countryside, making his way to safety in La Rochelle two days later (2). Meanwhile, on the 16th June, The Anglo-Portugese Treaty of 1373 established an alliance between the two states and strengthened English interests in Iberia. The Captal de Buch returned to England soon afterwards, where he in partnership with the Duke of Lancaster and Prince of Wales, prepared a force that would reinforce Aquitaine, wreak havoc in France and if possible bring Bertrand de Guesclin to battle.

In 1373 Jean IV de Montfort, Duke of Brittany arrived in England after having been driven out by his own nobles and Charles V. However, Charles V decided to hand the Duchy over to his own brother the Duc d'Anjou. Jean de Montfort's arrival was quickly followed by pleas asking the English to divert their planned invasion to help return him to Brittany, with a promise of allegiance to England in return. Edward III and his advisors were quick to leap at this opportunity, hoping to add this goal to the many others given to the invasion.

The following invasion of France, launched from Calais in August 1373, was commanded by John of Gaunt with the Captal de Buch in support. It was modelled partly off Robert Knolles invasion three years but with the added goal of restarting the war in Brittany (3). The almost 8,000 soldiers marched across northern France, burning and pillaging as they moved, entering Normandy by Late August and raiding the lands surrounding Rouen. Finding their way blocked and the city prepared for a siege, the army swung south towards Paris causing the city to be gripped by panic. The army crossed the Seine north of Paris and launched itself into the heartland of France, marching in three columns and pillaging all before them. The sudden appearance of this army came as a shock to the French and a loud clamor for action was raised by the French nobility who wished to bring their foes to combat. Charles V, King of France, fully aware of the dangers posed by a field battle denied the nobility their wishes and ordered them to burn what they could before the English army, and in so doing starve the army of resources. This decision, while highly unpopular, was committed to by the French who gathered their dependents in fortified cities and castles before starting work to deny their enemy any form of support.

At the same time Jean de Montfort arrived in Brest, Brittany with a smaller force of 3,000 and began besieging and capturing castles and towns in northern Brittany, taking Saint-Pol-De-Léon and besieging St. Brieuc by late September. Olivier de Clisson begins to build up a force to expel Montfort, eventually gathering around 5,000 men to his banner.

As the army bypassed Chartres in early September and moved into the Duchy of Maine the voice of the Duc d'Anjou, brother to King Charles V joined the other voices demanding action. These calls reached fever pitch as the army neared Brittany with the end result that Bertrand de Guesclin was called north to join Olivier de Clisson in preventing the two forces under Montfort and John of Gaunt from linking up with each other. The army under John of Gaunt arrived in the vicinity of Vitré at the crossroads of Normandy, Maine and Brittany in late September. Meanwhile, Montfort abandoned the Siege of St. Brieuc and swelling his ranks upon the news of Gaunt's arrival in Britanny, marched to meet up with his allies.

Bertrand de Guesclin linked up with his ally Olivier de Clisson, bringing their combined force to around 11,000 men and began marching northwards to intercept Montfort before he could link up with Gaunt. The first forces to run into each other are those of Lancaster and Guesclin near Rennes, where the exhausted English, who had just crossed most of France in little more than two months, found themselves faced with a force almost half again as large as their own to their south. The English moved northwards, hoping to evade this force, but were given chase by the French forces. For days the two sides skirmished as the English sought to escape while the French tried to bring their prey to heel. Three days into this chase the English made contact with Montfort's scouts and told them to hurry to their aid. Two days later, on the 9th of October, 1373, just north of Rennes, near the village of Aubigné the three forces collided in one of the largest battles of the war.

The Battle of Aubigné

The Battle of Aubigné sees more 22,000 men clash in the fields east of the village, at first between the forces under Lancaster and Guesclin. Rising on the morning of the 9th John Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster took the field in command of the center, ably served by John III de Grailly, Captal de Buch who had been given command of the right wing and by William de Montague, Second Earl of Salisbury who commanded the left wing of the army. Their army was a mixed force of veteran men-at-arms, knights and archers so common to the English forces of the wars and close to 7,500 strong. The French forces outnumbered their foes by more than three thousand men, and were also composed of a mixture of men-at-arms, knights and archers though far fewer and relegated to the rear as per common French tradition of the time. The two sides clashed around noon, the French were bombarded by the English archers from behind well protected positions placed between the wings and center of the English formation. As arrows rained down upon the French forces the French charged across the field. The two sides found themselves bound tightly together in a struggle to the death, the field turning to mud under the combatants as the English were slowly but steadily forced back. As the hours passed and the weak October sun moved across the sky to the cries of the combatant, Jean de Montfort arrived from behind the village of Aubigné with his vanguard of 300 knights who were immediately sent into the side of the French formation. The ensuing chaos swiftly degenerated into a bloody free-for-all as more and more of Montfort's forces arrive. By nightfall the two sides were finally able to disengage, with the English encamping near Aubigné with Montfort while the French did so to the south. Left on the field are more than 6,000 dead and wounded equally split between the two sides.

The following day, the two sides lined up to meet in battle once more, this time with equal numbers on both sides, however they were interrupted by Cardinal Jean de Murat de Cros, newly appointed grand penitentiary, who demandedthat the two sides break off their conflict and brought a demand from Pope Gregory XI to end their conflict. The two sides, after much disapproval and disagreement on both sides, disengaged, with the English forces moving towards Brest while the French withdrew south to Rennes. Messages were sent to both Edward III and Charles V to start negotiations under a truce starting in 1374 in Bruges, Flanders (4).

Footnotes:

(1) This is the POD. In OTL Edward of Angoulême died of the plague in late 1370 or early 1371. His death came as a shock to Edward, Black Prince of Wales who was never the same afterwards and the loss of his eldest son has been credited with worsening the already bad health of the prince.

(2) IOTL the Captal de Buch was captured for the third time in this encounter. He was imprisoned in the Temple in Paris and kept imprisoned without ransom thereafter. He was considered too great of a risk to allow him to go free by King Charles V of France despite the pleas of not only English royalty and nobility, but French Nobility as well. He was therefore left in the Temple until his death, shortly after learning of the death of his close friend and ally Edward, Prince of Wales.

(3) This is largely the force that IOTL became the Great Chevauchée under John of Gaunt. Over the course of four months John of Gaunt and his army raided France, marching around Paris, through Burgundy and Auvergne before arriving in Aquitaine that winter. The expedition, while hailed as a bold move ultimately proved unsuccessful and led to immense anger and resentment in England, which only grew worse as Lancaster grew to the most important political figure in England soon after.

(4) IOTL negotiations started somewhat later on what became the Treaty of Bruges and was only accepted by Edward III after the loss of almost all English territories in France. This time around the English retain Angoulême and some of the lands south of it, as well as the land corridor south to Navarre and a large part of northern Brittany. This leaves them much better off than OTL, but still represent devastating losses to the English. The Battle of Aubigné serves to drive both sides to exhaustion and end Guesclin's series of conquests in Aquitaine.

I have been reading timelines for years, so I thought it was time to start contributing. So without much further ado I would like to present:

The Dead Live: A Hundred Years' War Timeline

A Princely Miracle

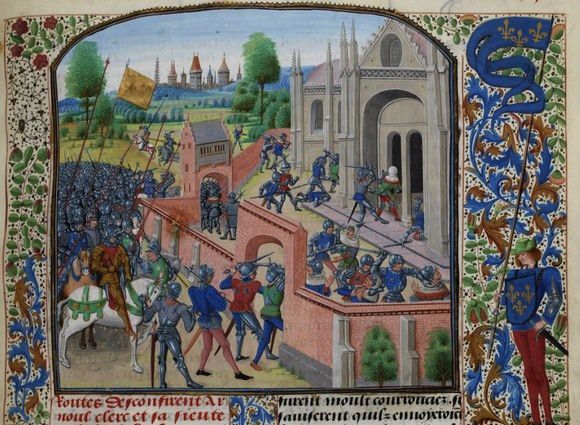

Depiction of Edward of Angoulême's Recovery

A Princely Miracle

Depiction of Edward of Angoulême's Recovery

In September of 1370 a young boy lay dying of the dread plague which had swept across Europe in a series of deadly waves. Tales of his brave warrior father had always been a source of wonder, comfort and fascination to the young boy, however, that image is but one of many surrounding the man who would in time become known as The Black Prince in a world that would never be. As his son lay dying Edward, Prince of Wales, prepared to leave the smoldering ruins of Limoges behind. The city, which had thrown open its gates to the Duc de Berry, had been properly punished for its inconstancy. Three thousand men, women and children who lived in the city had been given over to his troops, who had sacked the city in a brutal lesson to any who would betray the might of England. The siege and sack had utterly sapped the energy from the sickly prince, who had suffered from amoebic dysentery since his campaigns in Spain in previous years.

Edward of Angoulême, the young boy, took a turn for the worse as his father neared the city of Bordeaux and priests were called to give the boy his last rites. However, at that moment a miracle occurred and the boy stabilized. With his sick and exhausted father and terrified mother at his side the boy slowly recovered from the horrific disease (1). Bells were rung across Bordeaux in celebration of Edward's survival, as the tale of his miraculous recovery spreads and his relieved parents prepare to leave the lands which they had called home for the last many years. By the new year Edward of Angoulême had recovered fully from his sickness and, together with his family, left Aquitaine for England where his grandfather awaited. Left behind to defend the English possessions in France was Edward's uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster alongside Jean III de Grailly, Captal de Buch, one of the greatest military leaders on the English side. Throughout the year, John of Gaunt fought hard to retain what he could of Aquitaine, but he found himself under constant pressure and without proper support. By late 1371 John of Gaunt married Infanta Constance of Castile, claimant to the Castilian throne, thereby securing a claim to Castilian throne and prepared to leave for England.

The Battle of La Rochelle

As the Prince of Wales and his family settled into their home at Wallingford Castle in Berkshire hoping to recover his health, the war in France intensified under the constant French assaults led by the wily Breton Constable of France Bertrand de Guesclin on the lands and territories of England and its allies while the fleets of Castile worked to interdict the English convoys connecting Aquitaine to England. In June 1372 the Castilian Fleet intercepted a English convoy under the command of the Earl of Pembroke near La Rochelle. Over the subsequent two days the English ships carrying enought pay to support 3,000 combatants for a year and reinforcements of horse and men were sunk. This weakened the English forces in Aquitaine significantly, endangered the communications between Bordeaux and England, and opened the path to French raids on England. Edward III set off with a large fleet of impressed merchant ships to beat back the Castilians and open the rout to Bordeaux once more. However, this fleet found itself defeated by contrary winds which blew for weeks on end until it became too late in the year to sail, thereby ending with Edward having to concede before the whims of weather and sea.

The loss of the convoy in June led to a French attempt at taking the port of La Rochelle and its hinterlands. In the subsequent fighting the Captal de Buch and his forces were ambushed at night by a landing party of French forces under the renowned Welsh mercenary and claimant Prince of Wales Owain Lawgoch. In the subsequent fighting the Captal was almost captured, only making his way to safety by fighting on by torchlight and escaping into the countryside, making his way to safety in La Rochelle two days later (2). Meanwhile, on the 16th June, The Anglo-Portugese Treaty of 1373 established an alliance between the two states and strengthened English interests in Iberia. The Captal de Buch returned to England soon afterwards, where he in partnership with the Duke of Lancaster and Prince of Wales, prepared a force that would reinforce Aquitaine, wreak havoc in France and if possible bring Bertrand de Guesclin to battle.

In 1373 Jean IV de Montfort, Duke of Brittany arrived in England after having been driven out by his own nobles and Charles V. However, Charles V decided to hand the Duchy over to his own brother the Duc d'Anjou. Jean de Montfort's arrival was quickly followed by pleas asking the English to divert their planned invasion to help return him to Brittany, with a promise of allegiance to England in return. Edward III and his advisors were quick to leap at this opportunity, hoping to add this goal to the many others given to the invasion.

The following invasion of France, launched from Calais in August 1373, was commanded by John of Gaunt with the Captal de Buch in support. It was modelled partly off Robert Knolles invasion three years but with the added goal of restarting the war in Brittany (3). The almost 8,000 soldiers marched across northern France, burning and pillaging as they moved, entering Normandy by Late August and raiding the lands surrounding Rouen. Finding their way blocked and the city prepared for a siege, the army swung south towards Paris causing the city to be gripped by panic. The army crossed the Seine north of Paris and launched itself into the heartland of France, marching in three columns and pillaging all before them. The sudden appearance of this army came as a shock to the French and a loud clamor for action was raised by the French nobility who wished to bring their foes to combat. Charles V, King of France, fully aware of the dangers posed by a field battle denied the nobility their wishes and ordered them to burn what they could before the English army, and in so doing starve the army of resources. This decision, while highly unpopular, was committed to by the French who gathered their dependents in fortified cities and castles before starting work to deny their enemy any form of support.

At the same time Jean de Montfort arrived in Brest, Brittany with a smaller force of 3,000 and began besieging and capturing castles and towns in northern Brittany, taking Saint-Pol-De-Léon and besieging St. Brieuc by late September. Olivier de Clisson begins to build up a force to expel Montfort, eventually gathering around 5,000 men to his banner.

As the army bypassed Chartres in early September and moved into the Duchy of Maine the voice of the Duc d'Anjou, brother to King Charles V joined the other voices demanding action. These calls reached fever pitch as the army neared Brittany with the end result that Bertrand de Guesclin was called north to join Olivier de Clisson in preventing the two forces under Montfort and John of Gaunt from linking up with each other. The army under John of Gaunt arrived in the vicinity of Vitré at the crossroads of Normandy, Maine and Brittany in late September. Meanwhile, Montfort abandoned the Siege of St. Brieuc and swelling his ranks upon the news of Gaunt's arrival in Britanny, marched to meet up with his allies.

Bertrand de Guesclin linked up with his ally Olivier de Clisson, bringing their combined force to around 11,000 men and began marching northwards to intercept Montfort before he could link up with Gaunt. The first forces to run into each other are those of Lancaster and Guesclin near Rennes, where the exhausted English, who had just crossed most of France in little more than two months, found themselves faced with a force almost half again as large as their own to their south. The English moved northwards, hoping to evade this force, but were given chase by the French forces. For days the two sides skirmished as the English sought to escape while the French tried to bring their prey to heel. Three days into this chase the English made contact with Montfort's scouts and told them to hurry to their aid. Two days later, on the 9th of October, 1373, just north of Rennes, near the village of Aubigné the three forces collided in one of the largest battles of the war.

The Battle of Aubigné

The Battle of Aubigné sees more 22,000 men clash in the fields east of the village, at first between the forces under Lancaster and Guesclin. Rising on the morning of the 9th John Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster took the field in command of the center, ably served by John III de Grailly, Captal de Buch who had been given command of the right wing and by William de Montague, Second Earl of Salisbury who commanded the left wing of the army. Their army was a mixed force of veteran men-at-arms, knights and archers so common to the English forces of the wars and close to 7,500 strong. The French forces outnumbered their foes by more than three thousand men, and were also composed of a mixture of men-at-arms, knights and archers though far fewer and relegated to the rear as per common French tradition of the time. The two sides clashed around noon, the French were bombarded by the English archers from behind well protected positions placed between the wings and center of the English formation. As arrows rained down upon the French forces the French charged across the field. The two sides found themselves bound tightly together in a struggle to the death, the field turning to mud under the combatants as the English were slowly but steadily forced back. As the hours passed and the weak October sun moved across the sky to the cries of the combatant, Jean de Montfort arrived from behind the village of Aubigné with his vanguard of 300 knights who were immediately sent into the side of the French formation. The ensuing chaos swiftly degenerated into a bloody free-for-all as more and more of Montfort's forces arrive. By nightfall the two sides were finally able to disengage, with the English encamping near Aubigné with Montfort while the French did so to the south. Left on the field are more than 6,000 dead and wounded equally split between the two sides.

The following day, the two sides lined up to meet in battle once more, this time with equal numbers on both sides, however they were interrupted by Cardinal Jean de Murat de Cros, newly appointed grand penitentiary, who demandedthat the two sides break off their conflict and brought a demand from Pope Gregory XI to end their conflict. The two sides, after much disapproval and disagreement on both sides, disengaged, with the English forces moving towards Brest while the French withdrew south to Rennes. Messages were sent to both Edward III and Charles V to start negotiations under a truce starting in 1374 in Bruges, Flanders (4).

Footnotes:

(1) This is the POD. In OTL Edward of Angoulême died of the plague in late 1370 or early 1371. His death came as a shock to Edward, Black Prince of Wales who was never the same afterwards and the loss of his eldest son has been credited with worsening the already bad health of the prince.

(2) IOTL the Captal de Buch was captured for the third time in this encounter. He was imprisoned in the Temple in Paris and kept imprisoned without ransom thereafter. He was considered too great of a risk to allow him to go free by King Charles V of France despite the pleas of not only English royalty and nobility, but French Nobility as well. He was therefore left in the Temple until his death, shortly after learning of the death of his close friend and ally Edward, Prince of Wales.

(3) This is largely the force that IOTL became the Great Chevauchée under John of Gaunt. Over the course of four months John of Gaunt and his army raided France, marching around Paris, through Burgundy and Auvergne before arriving in Aquitaine that winter. The expedition, while hailed as a bold move ultimately proved unsuccessful and led to immense anger and resentment in England, which only grew worse as Lancaster grew to the most important political figure in England soon after.

(4) IOTL negotiations started somewhat later on what became the Treaty of Bruges and was only accepted by Edward III after the loss of almost all English territories in France. This time around the English retain Angoulême and some of the lands south of it, as well as the land corridor south to Navarre and a large part of northern Brittany. This leaves them much better off than OTL, but still represent devastating losses to the English. The Battle of Aubigné serves to drive both sides to exhaustion and end Guesclin's series of conquests in Aquitaine.