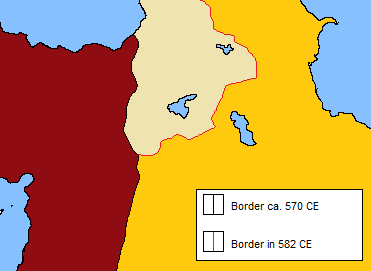

King Liuvigild and Hispania, 568 - 583 CE

When studying the history of Hispania from the 5th to the 8th Centuries, it's important to realize that the kingdom which then occupied the Iberian Peninsula could not yet be identified with the nation-state we know of today (not least because the concept of a nation-state did not yet exist). In this period, the post-Roman kingdom in the former provinces of Hispania was based on a tenuous cooperation between its Arian, Germanic ruling class, and the Ibero-Roman, Catholic masses

[1]. A Hispanian identity was centuries away, and so this state is more accurately termed the Kingdom of the Visigoths.

Nevertheless, the greatest monarch of this period is included in the ranks of the great 'Hispanian' national heroes, filling the textbooks of primary school history classes all over the Iberian Peninsula. Born around 525 CE, Liuvigild in his earliest years is poorly attested, perhaps because he had not been born into the family which then ruled the Visigothic kingdom. He enters the realm of historical knowledge in 567 as the brother of a usurper, Liuva I, who rose to the throne upon the death of Athanagild.

Liuva was crowned at Narbonne, the center of Visigothic Septimania, likely due to the threat of possible Frankish intervention in the Visigothic succession, and made his brother his co-king, assigning him to the east. As it was, however, the Franks were embroiled in yet another one of the internecine wars to which they were prone, and as such interfered little in Hispania. When his brother passed away in 572, Liuvigild became sole king of the Visigoths, inheriting a kingdom which had faced an uncertain future since the Battle of Vouille in 507. It was his efforts to reinforce the position of the Visigoths on the peninsula which would earn him his legacy, and, eventually, form the nucleus of a Hispanian state.

Even before ascending to the position of sole king, Liuvigild had captured the cities of Asidona and Malaga, lost to the Visigoths at the hands of Justinian at the beginning of Athanagild's reign. Although he seized Cordoba, Malaga fell again to the Romans in 575, and the coastal cities of Carthago Spartaria and Gades, supplied by the powerful Roman fleet by sea, were outside of his grasp. By the next year, Liuvigild was compelled to offer a ceasefire, seeing that little more could be gained from the conflict. Although the coastal cities and Asidona would remain under Constantinople's purview, Seville and Cordoba, along with the rest of the cities of the rich Guadalquivir valley, were secured for the Visigoths. This accomplished, the king turned his attention away from the Romans, who were embroiled in a brutal war with the Sassanids, to secure the untamed, mountainous north for the Visigothic kingdom.

As with Roman Spania, however, the rugged backwater of Cantabria was to prove equally frustrating for the king. Although the major regional center of Amaya fell quickly to the much larger armies of the Visigoths, the Cantabrians proved a resilient foe, holding out to the north of the Cantabrian Mountains. By 578, Liuvigild ended the campaign, establishing the Duchy of Amaya

[2] around the captured city as a means of governing the unruly, newly-conquered region. The frontier was a to prove a nebulous one, as for the next decade, the vengeful Cantabrians continued to raid Visigothic positions, even assailing Amaya several times. The new duchy would prove to be almost a legal fiction, and banditry the law of the land. Although the failure stung, Liuvigild's hands were tied as a major Catholic rebellion flared in recently-reconquered Seville.

Although the Visigothic state had been relatively fair to its Catholic subjects in the past, the change of the city's control from an orthodox state to a heretical one led to considerable insecurities amongst the Catholics of Seville. Several Catholic priests who were alleged to have spoken against their new overlords were arrested in the later months of 577. The ensuing public outcry faded by the new year, but the embers of discontent in the city were fanned again when, in March of 578, rumors spread in the city of Visigothic soldiers harassing Catholic women as mass was letting out. Whether true or not, riots wracked Seville as a result, and the ensuing putting down of these riots only exacerbated the situation. As summer began, the entire area of Seville, as far afield as Carmona, was in a state of revolt.

It should come as no surprise that the revolt could not remain a going force for long once the king and his armies arrived, as full royal control in the city was reestablished before 579. One Leander, a promising Benedictine monk

[3], was accused of helping to spark the revolts. Leander fled east, narrowly ahead of the Visigoths, arriving first in Carthago Spartaria, his family's original home. With little promise of returning to his home in Seville, Leander departed further east, to the city of Ravenna in Roman Italy, hoping to make his mark in the Empire rather than in his native Hispania. Liuvigild could turn his attention north once more, although sporadic rebellions springing from those of 578 would continue to plague the heavily Catholic countryside until the 590s.

Seeking to drive home his superiority over the Catholics, Liuvigild looked to the northwest, towards the only major region of Hispania that remained outside of Visigoth control - Gallaecia. In the northwestern corner of the peninsula, the Suebi, another Germanic people who had taken control of former Roman lands in the west, had recently converted to orthodox Christianity, abandoning the Arian faith which had previously been common to many of the 'barbarian' kingdoms of western Europe.

After some time to prepare his forces for war, Liuvigild took his armies north to Gallaecia in 581. The Suebi king, Miro, met Liuvigild near the city of Portus Cale, and after a week of fierce fighting, was routed, fleeing north to the capital at Braga. The coming of winter forced Liuvigild and his men to winter in the captured city of Portus Cale, and the campaign resumed the following spring. The Suebi, fortifying their capital with all of their might, frustrated the assaults of the Visigothic army, but as the months pressed on, the garrison of the city began to grow weary. Just as the Suebi were near capitulation, however, fortune struck - Liuvigild became violently ill

[4], and the Visigoths wavered. At the urging of his son, Hermenegild

[5], Liuvigild settled for a simple declaration of fealty from Miro (who acquiesced, although his fealty would be in name only), lifted the siege, and returned home in disappointment.

Liuvigild lingered at the palace in Toledo for another year, eventually succumbing to his illness on 4 April 583. Hermenegild, who had been associated as co-king three years before, became King of the Visigoths, inheriting a kingdom markedly more powerful than it had been a decade and a half before. Although historians would criticize Liuvigild's reign as one of only half-successes, he left his kingdom more stable and militarily more powerful, and brought the Visigoths their first significant gains since Vouille.

It would be six decades before another great monarch would rule the Visigothic nation.

The Visigothic kingdom at Liuvigild's death, in 583 CE.

Olive Green: Visigoths. Red: Roman Empire. Gray: Suebi. Yellow: Cantabrians. Pale Blue: Vasconia. Pink: Kingdom of Charibert I. Green: Kingdom of Sigebert I. Lavender: Kingdom of Burgundy.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] - Pun absolutely intended.

[2] - In OTL the Duchy of Cantabria, although the fact that it is so reduced in size ITTL and so neutered in power has lent itself a less impressive-sounding historiographic term.

[3] - IOTL, St. Leander of Seville, who was instrumental in converting Liuvigild's sons to Catholicism.

[4] - Later Visigothic and Hispanian historians blame the foul air and water of Gallaecia.

[5] - Who has not converted to Catholicism and rebelled as he did IOTL.