You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Soviets in the Sun: A Timeline

- Thread starter Comisario

- Start date

Book I- The Spanish War of Liberation

Chapter 4

War in the Shadows

The offensive against Santander was coordinated with Spanish and Italian troops attacking on the ground whilst the German Condor Legion would provide air support. Franco knew that taking the port of Santander and defeating the remnants of the Army of the North would mean the collapse of the entire Republican effort in the north. Without Ulibarri and his army as a thorn in the Spanish State's side, Franco could organise large-scale offensives in Aragon to retake that front. At this point, the Caudillo believed the fall of Zaragoza to be imminent, and thus did not want to waste valuable manpower and resources to relieve a forsaken city. Reconnaissance around the mountains guarding Santander revealed that the Republican forces' positions were heavily fortified and would be hard to breach [1]. Still, Franco believed that his pursuit of the Army of the North, which had been interrupted by the political fallout after Brunete, had to be resumed if Nationalist victory in central and eastern Spain was to be guaranteed. The battle began with the three Italian divisions under General Bastico attacking from the southwest, trying in vain to force a breakthrough in the mountain range that stood as an affront to the Nationalist advance to Santander. Under the recently redeployed General Solchaga were six brigades of Navarrese Carlists. They focused their attack from the southwest. Air support came with over 200 planes, split amongst the Condor Legion, Legionary Air Force and a few Nationalist squadrons. During this intense fighting, Ulibarri's 80,000 men kept their defensive positions and forced back many Nationalist attacks. To maximise his army's chances at survival, Ulibarri developed a new tactic of firing his new Soviet artillery at the tips of the mountains in case of a successful Nationalist advance. He would order a retreat from the mountain pass, fire shells at the mountaintops, and then watch as the resulting rockfall crushed the Nationalists and blocked the pass. This tactic, coupled with the morale boosts from the Republic's victories across Spain, would see the Army of the North through until 1938.

Basque soldiers defending their position at the Escudo Pass.

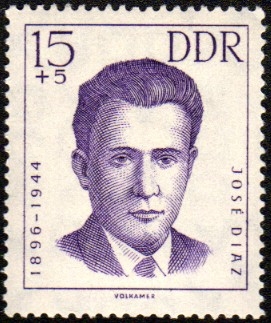

When Zaragoza finally fell on the 10th August, the Nationalists' front in Aragon fell with it [2]. Panic set in as the entire front's communications were taken over by the Republican forces, turning the Nationalist retreat to Calatayud and the "Navarrese corridor" a logistical nightmare. In the wake of Aragon's consolidation back into the Republic, the Communist Party decided to establish a power base in northeastern Spain. Masterminded by the Party's General Secretary, José Díaz Ramos, a new authority was to be extended over Catalonia. The idea of the "Consejo Popular del Este" was to ensure the Communist Party could rely on a non-military body to safeguard its interests in Catalonia and Aragon. On the 17th August, José Díaz offered formal unification between the PSOE and the PCE, to which Juan Negrín declined. Instead, a unity pact was signed between the two parties as a sign of solidarity [3]. To the plan for the "Consejo Popular del Este", Prime Minister Negrín readily agreed, believing Díaz to be working in the government's interests and believing he was depriving the Communists of major influence with the central government by relegating them to the provincial northeast [4]. Stalin, whose policy of balancing intervention in Spain with forming an anti-fascist alliance with Britain and France was still in practice, gave his unofficial approval to the plan through the Soviet ambassador to Spain, Marcel Rosenberg. On the 20th August, José Díaz established the council with Juan García Oliver as its president. Juan García, although a member of the anarchist CNT, had been in close collaboration with the Communists. He had called for peace during the Barcelona May Days, opposing the CNT-FAI's revolution and promoting state control over Catalonia. He would be invaluable in suppressing further anarchist uprisings against Communist authority.

Juan García Oliver as President of the People's Council of the East [5].

Prior to the People's Council of the East's conception was the creation of the "Servicio de Investigacíon Militar". A continuation of the former communist counter-intelligence service "DEDIDE", the SIM became a new organ of the Party's authority within the Popular Front. The NKVD would have considerable influence over the SIM [6]. The Soviets had control over the training of the SIM agents, and informed it of Nationalist fifth-columnists and opposing left-wing elements such as anarchists and libertarian socialists. The SIM, although operating mainly in Madrid, also coordinated their intelligence operations with the CPE in Barcelona. With the relative peace in the Republican zone, a purge took place in Catalonia. On the 22nd August, Jaime Balius Mir, an anarchist writer and outspoken anti-communist, publicly voiced his opposition to the new council. He had a lot of support, especially from the FAI, which was the most radical anarchist group in Catalonia. The threat of a split in the CNT between its moderate and anarchist wings instilled fear in the Communist Party leadership. It could have led to the disestablishment of the CPE and the return of anarchy to the Aragon Front. José Díaz met with Juan García Oliver and agreed to silence the restless anarchists, who now had the support of the CNT's Secretary General, Mariano Rodríguez Vázquez. On the 27th August, SIM and NKVD operatives forcefully entered the homes of Mariano and Jaime, stealing them away in the middle of the night and driving them down to the mouth of the Ebro. Hands bound and blindfolded, the two anarchist leaders were executed and dumped into the Ebro. The People's Council of the East created a story stating that the former anarchist leaders had fled to France and had "abandoned their revolutionary struggle in the face of fascist aggression". In Mariano Vázquez's "absence", a new leader was to be elected. The moderate wing of the CNT, headed by Juan García and Federica Montseny, was more unified and had support from the Communist Party. Those who opposed García Oliver's bid for power were deeply divided following their leaders' disappearances, and thus lost the election [7]. The Republic's unity was fragile, but such political cohesion had not been seen since the civil war began.

The purged anarchists (left to right): Jaime Balius Mir and Mariano Rodríguez Vázquez

A tenuous grip was better than none.

***

[1] A hard truth that Franco will be unable to face ITTL.

[2] Zaragoza was the beating heart of the Nationalist war effort in Aragon. In OTL, the Republicans came incredibly close to capturing it.

[3] As in OTL.

[4] The Prime Minister will one day see how wrong he was.

[5] A position he will not be holding forever.

[6] As it did in OTL.

[7] This will mark the beginning of the end for Spanish anarchism.

Chapter 4

War in the Shadows

The offensive against Santander was coordinated with Spanish and Italian troops attacking on the ground whilst the German Condor Legion would provide air support. Franco knew that taking the port of Santander and defeating the remnants of the Army of the North would mean the collapse of the entire Republican effort in the north. Without Ulibarri and his army as a thorn in the Spanish State's side, Franco could organise large-scale offensives in Aragon to retake that front. At this point, the Caudillo believed the fall of Zaragoza to be imminent, and thus did not want to waste valuable manpower and resources to relieve a forsaken city. Reconnaissance around the mountains guarding Santander revealed that the Republican forces' positions were heavily fortified and would be hard to breach [1]. Still, Franco believed that his pursuit of the Army of the North, which had been interrupted by the political fallout after Brunete, had to be resumed if Nationalist victory in central and eastern Spain was to be guaranteed. The battle began with the three Italian divisions under General Bastico attacking from the southwest, trying in vain to force a breakthrough in the mountain range that stood as an affront to the Nationalist advance to Santander. Under the recently redeployed General Solchaga were six brigades of Navarrese Carlists. They focused their attack from the southwest. Air support came with over 200 planes, split amongst the Condor Legion, Legionary Air Force and a few Nationalist squadrons. During this intense fighting, Ulibarri's 80,000 men kept their defensive positions and forced back many Nationalist attacks. To maximise his army's chances at survival, Ulibarri developed a new tactic of firing his new Soviet artillery at the tips of the mountains in case of a successful Nationalist advance. He would order a retreat from the mountain pass, fire shells at the mountaintops, and then watch as the resulting rockfall crushed the Nationalists and blocked the pass. This tactic, coupled with the morale boosts from the Republic's victories across Spain, would see the Army of the North through until 1938.

Basque soldiers defending their position at the Escudo Pass.

When Zaragoza finally fell on the 10th August, the Nationalists' front in Aragon fell with it [2]. Panic set in as the entire front's communications were taken over by the Republican forces, turning the Nationalist retreat to Calatayud and the "Navarrese corridor" a logistical nightmare. In the wake of Aragon's consolidation back into the Republic, the Communist Party decided to establish a power base in northeastern Spain. Masterminded by the Party's General Secretary, José Díaz Ramos, a new authority was to be extended over Catalonia. The idea of the "Consejo Popular del Este" was to ensure the Communist Party could rely on a non-military body to safeguard its interests in Catalonia and Aragon. On the 17th August, José Díaz offered formal unification between the PSOE and the PCE, to which Juan Negrín declined. Instead, a unity pact was signed between the two parties as a sign of solidarity [3]. To the plan for the "Consejo Popular del Este", Prime Minister Negrín readily agreed, believing Díaz to be working in the government's interests and believing he was depriving the Communists of major influence with the central government by relegating them to the provincial northeast [4]. Stalin, whose policy of balancing intervention in Spain with forming an anti-fascist alliance with Britain and France was still in practice, gave his unofficial approval to the plan through the Soviet ambassador to Spain, Marcel Rosenberg. On the 20th August, José Díaz established the council with Juan García Oliver as its president. Juan García, although a member of the anarchist CNT, had been in close collaboration with the Communists. He had called for peace during the Barcelona May Days, opposing the CNT-FAI's revolution and promoting state control over Catalonia. He would be invaluable in suppressing further anarchist uprisings against Communist authority.

Juan García Oliver as President of the People's Council of the East [5].

Prior to the People's Council of the East's conception was the creation of the "Servicio de Investigacíon Militar". A continuation of the former communist counter-intelligence service "DEDIDE", the SIM became a new organ of the Party's authority within the Popular Front. The NKVD would have considerable influence over the SIM [6]. The Soviets had control over the training of the SIM agents, and informed it of Nationalist fifth-columnists and opposing left-wing elements such as anarchists and libertarian socialists. The SIM, although operating mainly in Madrid, also coordinated their intelligence operations with the CPE in Barcelona. With the relative peace in the Republican zone, a purge took place in Catalonia. On the 22nd August, Jaime Balius Mir, an anarchist writer and outspoken anti-communist, publicly voiced his opposition to the new council. He had a lot of support, especially from the FAI, which was the most radical anarchist group in Catalonia. The threat of a split in the CNT between its moderate and anarchist wings instilled fear in the Communist Party leadership. It could have led to the disestablishment of the CPE and the return of anarchy to the Aragon Front. José Díaz met with Juan García Oliver and agreed to silence the restless anarchists, who now had the support of the CNT's Secretary General, Mariano Rodríguez Vázquez. On the 27th August, SIM and NKVD operatives forcefully entered the homes of Mariano and Jaime, stealing them away in the middle of the night and driving them down to the mouth of the Ebro. Hands bound and blindfolded, the two anarchist leaders were executed and dumped into the Ebro. The People's Council of the East created a story stating that the former anarchist leaders had fled to France and had "abandoned their revolutionary struggle in the face of fascist aggression". In Mariano Vázquez's "absence", a new leader was to be elected. The moderate wing of the CNT, headed by Juan García and Federica Montseny, was more unified and had support from the Communist Party. Those who opposed García Oliver's bid for power were deeply divided following their leaders' disappearances, and thus lost the election [7]. The Republic's unity was fragile, but such political cohesion had not been seen since the civil war began.

The purged anarchists (left to right): Jaime Balius Mir and Mariano Rodríguez Vázquez

A tenuous grip was better than none.

***

[1] A hard truth that Franco will be unable to face ITTL.

[2] Zaragoza was the beating heart of the Nationalist war effort in Aragon. In OTL, the Republicans came incredibly close to capturing it.

[3] As in OTL.

[4] The Prime Minister will one day see how wrong he was.

[5] A position he will not be holding forever.

[6] As it did in OTL.

[7] This will mark the beginning of the end for Spanish anarchism.

Last edited:

Razgriz 2K9

Banned

Do you think that with the destruction of the CNT's leadership, would some pro-communist anarchists side with the Spanish Communist Party?

The Republic seems to have the upper hand but from what you've posted before (such as Franco being just the first Caudilho) the war is still far from decided

The next Caudillo may or may not come to power in this war, so I wouldn't try to infer too much about the Nationalists' future status from past mentions of this mysterious man.

Do you think that with the destruction of the CNT's leadership, would some pro-communist anarchists side with the Spanish Communist Party?

Some would, if only for pragmatic reasons. Although, that will not guarantee them all safety in the new Spain.

I've been so busy with DIY work and exam revision lately, so that's why this next update has been slow in coming. But, I do have a little teaser to tide everyone over...

(The first one to note the alternate history in this image will... erm... win the Internet or something)

(The first one to note the alternate history in this image will... erm... win the Internet or something)

Last edited:

Why does that say DDR? Wasn't that the German Democratic Republic.

The German Democratic Republic will exist in this timeline. Also, it was common practice to put other communist leaders on stamps to pay homage to them. But the AH is more to do with the figure on the stamp...

Great TL

While the front specific maps are great. I know very little about the Spanish Civil war, so can we have an overall map of Spain?

While the front specific maps are great. I know very little about the Spanish Civil war, so can we have an overall map of Spain?

Great TL

While the front specific maps are great. I know very little about the Spanish Civil war, so can we have an overall map of Spain?

Thank you very much, and don't forget to tell your friends! Haha

I will post one in the morning as I'm not very close to a computer at the moment. This is being written on an iPod... my apologies

Thank you very much, and don't forget to tell your friends! Haha

I will post one in the morning as I'm not very close to a computer at the moment. This is being written on an iPod... my apologies

I know how you feel, most of my posts are on a tablet.

Razgriz 2K9

Banned

The German Democratic Republic will exist in this timeline. Also, it was common practice to put other communist leaders on stamps to pay homage to them. But the AH is more to do with the figure on the stamp...

Huh...the more you know.

5 bucks says he becomes the leader of Spanish Communism.

Huh...the more you know.

5 bucks says he becomes the leader of Spanish Communism.

Even if that's the case, chances are he'll be more of a Lenin-type figure to Red Spain considering the life span on that stamp - assuming that Red Spain somehow survives WWII.

Will this revolution spread to Portugal?

It will, but not before Spain's revolution has swept up the last of the reactionaries in its own borders.

Book I- The Spanish War of Liberation

Chapter 5

Red Autumn

September would start unremarkably for Spain. The Nationalist forces were still in retreat on the Aragon Front, leaving many of their positions for the rapidly advancing forces of the Republic. Calatayud would stand as the new centre for the Nationalist war effort in the northwest [1]. Although, the loss of equipment and intelligence in Aragon during the fall of Zaragoza would prove that this new centre was in an untenable position. Most importantly for the Republic, supply lines to Teruel had been cut off. Teruel had been defiant against the Republic since the civil war began, standing in the middle of a salient protruding into the Republican zone. Amongst the Republican General Staff, nobody believed that Teruel could withstand an encroaching encirclement. Indalecio Prieto, the Republic's Minister of National Defense, was against the constant pushes for an attack on Teruel [2]. His ministry had received intelligence that Franco was planning for a counteroffensive in Aragon, hoping to regain some of the ground his troops lost after the fall of Zaragoza. Prieto argued that, with Franco's troops regrouping in the northeast, an offensive in the west would have been better advised. After much deliberation, Toledo was chosen as the Republic's next target. Franco was the "saviour of the Alcázar": a Republican victory there would take away a large amount of his prestige. With Segismundo Casado, Prieto's ministry created the Army of Andalusia, in anticipation of the attack on Toledo [3].

Indalecio Prieto, the Republic's Minister of National Defence.

On the 17th September, Modesto's 5th Corps and Casado's Army of Andalusia attacked from the north and south, respectively, in a pincer attack. José Moscardó, who had defended the Alcázar in the early days of the civil war, commanded the garrison in Toledo. The attack was swift, accompanied by almost 70 Soviet bombers. The small garrison was quickly overwhelmed and, aside from small pockets of civil resistance, put up very little fight. Moscardó surrendered within three days of the attack. Franco, upon hearing of the Alcázar's fall, ordered half of the Nationalist forces amassing in Aragon to march back west and then south. The Generalissimo was incandescent with rage. Serrano Suñer attempted to calm him down, promising to gain more aid from Italy and Germany for future offensives in central and northeastern Spain. Franco dismissed his brother-in-law's promises, knowing no aid would come without an independent military victory. With Franco's forces split, the Republic knew another surprise attack would show a resumption of offensive strategy. As the Republican forces in Toledo prepared for a new offensive in the south, token forces of Nationalists tried to advance on Toledo. A week of small engagements around the western outskirts of the city went by without any serious damage to the Republicans' defences around the Alcázar. The second Siege of the Alcázar began, although it only lasted until the reinforcements from the north came in late September. Toledo's defences needed to be at their strongest.

Republican soldiers in the heart of the Alcázar of Toledo.

The General Staff could not let the chance for an Andalusian offensive go to waste, however. On the 7th October, Casado's Army of Andalusia was ordered south to Cordoba. Casado argued against the offensive, preferring to stay with the defenders of Toledo against Franco's newly arrived divisions. Colonel Casado was threatened with replacement should he not comply with his orders [4]. Segismundo relented. A separate amphibious assault on the coastal town of Motril in Granada was also planned [5]. Three brigades would be placed under the command of General Kléber and transported to Motril on the eve of October 12. The Andalusia Offensive opened on the 11th October with an advance on Cordoba. Casado's army of almost 70,000 men was split, half attacking from the north and half attacking from the east. Three divisions under Antonio Escobar Huertas moved quickly westwards from the town of Montoro, taking small unguarded villages over the course of the day. From Villaharta, the communist Colonel Luis Barceló led three divisions southwards. The element of surprise allowed Barceló and Escobar to make up considerable ground without any considerable resistance halting their attacks. By the afternoon of the 12th, however, Colonel Escobar Huertas found the town of Alcolea defended by a garrison of almost 10,000 that had been sent by the Nationalist "Viceroy of Andalusia", Gonzalo Queipo de Llano [6]. The Battle of Alcolea would take a harsh toll on both sides, continuing for almost a week. Barceló's troops were not so impeded, coming within 5 miles of Cordoba and taking Torreblanca after a few hours of urban fighting.

The Republican colonels in Andalusia (left to right): Segismundo Casado, Luis Barceló, and Antonio Escobar Huertas.

Torreblanca was under heavy artillery fire. Barceló, who wanted to advance quickly and reach Cordoba before the assault on Motril on the Granadan coast began, was pinned in the town centre. He tried to organise some rudimentary defences, expecting Nationalist forces to meet his in Torreblanca. Over the night of the 12th, Colonel Barceló waited for Queipo de Llano's troops. In Valencia, the government waited for news from Motril. Kléber had been escorted under the cover of darkness to the seaside town, springing upon the unguarded Nationalist port. There was little resistance as the Republic's flag was raised on the beach of Motril. Kléber was ecstatic, sending an optimistic report to the Ministry of National Defence. The following days were quiet in Motril, bloody in Torreblanca, and desperate in Alcolea. In Alcolea and Torreblanca, the struggles in the streets proved indecisive. Antonio Escobar Huertas was still very much stuck straddling the outskirts of Alcolea whilst Luis Barceló's soldiers found that their few breakthroughs out of the town limits were turned back within hours.

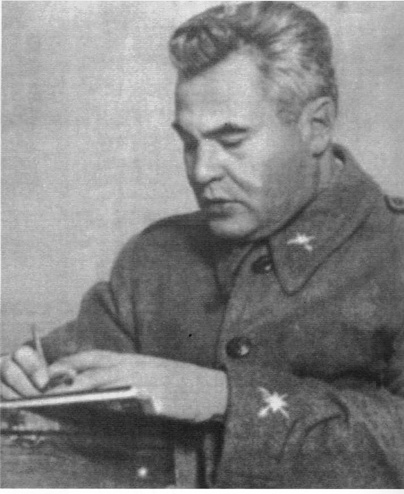

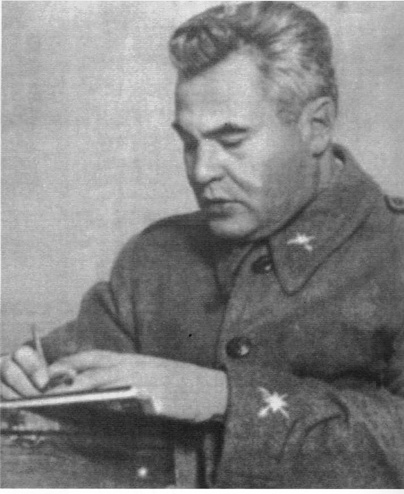

General Kléber writing his report from Motril.

On the 21st October, another report came in to Valencia. Indalecio Prieto was said to have demanded to see the entire General Staff as soon as the news reached him. In the early hours of the morning of the 21st October, Toledo had fallen to the Nationalists.

The ruins of Toledo that Franco would inherit.

***

[1] Though it will not stand forever.

[2] In OTL, Teruel was the last chance for a Republican military victory. The battle there was particularly gruesome and dealt a huge blow to the People's Republican Army. The Republic will dodge that bullet ITTL.

[3] In OTL, the Army of Andalusia would be formed a month or so later during a huge reorganization of the Republic's armed forces.

[4] Casado was an anti-communist, and was thus viewed with suspicion by many in the Republic's army and government.

[5] As it was in OTL. Though, the plans amounted to nothing.

[6] Queipo de Llano practically ruled Andalusia as his own personal kingdom. He built up an astounding cult of personality around himself from his post in Seville. When Franco first visited the general in late 1936, he found posters, mirrors and even ashtrays bearing Queipo de Llano's face on them. Although, the greatest affront to Franco was the Republican flag that Queipo de Llano still flew and believed in.

Chapter 5

Red Autumn

September would start unremarkably for Spain. The Nationalist forces were still in retreat on the Aragon Front, leaving many of their positions for the rapidly advancing forces of the Republic. Calatayud would stand as the new centre for the Nationalist war effort in the northwest [1]. Although, the loss of equipment and intelligence in Aragon during the fall of Zaragoza would prove that this new centre was in an untenable position. Most importantly for the Republic, supply lines to Teruel had been cut off. Teruel had been defiant against the Republic since the civil war began, standing in the middle of a salient protruding into the Republican zone. Amongst the Republican General Staff, nobody believed that Teruel could withstand an encroaching encirclement. Indalecio Prieto, the Republic's Minister of National Defense, was against the constant pushes for an attack on Teruel [2]. His ministry had received intelligence that Franco was planning for a counteroffensive in Aragon, hoping to regain some of the ground his troops lost after the fall of Zaragoza. Prieto argued that, with Franco's troops regrouping in the northeast, an offensive in the west would have been better advised. After much deliberation, Toledo was chosen as the Republic's next target. Franco was the "saviour of the Alcázar": a Republican victory there would take away a large amount of his prestige. With Segismundo Casado, Prieto's ministry created the Army of Andalusia, in anticipation of the attack on Toledo [3].

Indalecio Prieto, the Republic's Minister of National Defence.

On the 17th September, Modesto's 5th Corps and Casado's Army of Andalusia attacked from the north and south, respectively, in a pincer attack. José Moscardó, who had defended the Alcázar in the early days of the civil war, commanded the garrison in Toledo. The attack was swift, accompanied by almost 70 Soviet bombers. The small garrison was quickly overwhelmed and, aside from small pockets of civil resistance, put up very little fight. Moscardó surrendered within three days of the attack. Franco, upon hearing of the Alcázar's fall, ordered half of the Nationalist forces amassing in Aragon to march back west and then south. The Generalissimo was incandescent with rage. Serrano Suñer attempted to calm him down, promising to gain more aid from Italy and Germany for future offensives in central and northeastern Spain. Franco dismissed his brother-in-law's promises, knowing no aid would come without an independent military victory. With Franco's forces split, the Republic knew another surprise attack would show a resumption of offensive strategy. As the Republican forces in Toledo prepared for a new offensive in the south, token forces of Nationalists tried to advance on Toledo. A week of small engagements around the western outskirts of the city went by without any serious damage to the Republicans' defences around the Alcázar. The second Siege of the Alcázar began, although it only lasted until the reinforcements from the north came in late September. Toledo's defences needed to be at their strongest.

Republican soldiers in the heart of the Alcázar of Toledo.

The General Staff could not let the chance for an Andalusian offensive go to waste, however. On the 7th October, Casado's Army of Andalusia was ordered south to Cordoba. Casado argued against the offensive, preferring to stay with the defenders of Toledo against Franco's newly arrived divisions. Colonel Casado was threatened with replacement should he not comply with his orders [4]. Segismundo relented. A separate amphibious assault on the coastal town of Motril in Granada was also planned [5]. Three brigades would be placed under the command of General Kléber and transported to Motril on the eve of October 12. The Andalusia Offensive opened on the 11th October with an advance on Cordoba. Casado's army of almost 70,000 men was split, half attacking from the north and half attacking from the east. Three divisions under Antonio Escobar Huertas moved quickly westwards from the town of Montoro, taking small unguarded villages over the course of the day. From Villaharta, the communist Colonel Luis Barceló led three divisions southwards. The element of surprise allowed Barceló and Escobar to make up considerable ground without any considerable resistance halting their attacks. By the afternoon of the 12th, however, Colonel Escobar Huertas found the town of Alcolea defended by a garrison of almost 10,000 that had been sent by the Nationalist "Viceroy of Andalusia", Gonzalo Queipo de Llano [6]. The Battle of Alcolea would take a harsh toll on both sides, continuing for almost a week. Barceló's troops were not so impeded, coming within 5 miles of Cordoba and taking Torreblanca after a few hours of urban fighting.

The Republican colonels in Andalusia (left to right): Segismundo Casado, Luis Barceló, and Antonio Escobar Huertas.

Torreblanca was under heavy artillery fire. Barceló, who wanted to advance quickly and reach Cordoba before the assault on Motril on the Granadan coast began, was pinned in the town centre. He tried to organise some rudimentary defences, expecting Nationalist forces to meet his in Torreblanca. Over the night of the 12th, Colonel Barceló waited for Queipo de Llano's troops. In Valencia, the government waited for news from Motril. Kléber had been escorted under the cover of darkness to the seaside town, springing upon the unguarded Nationalist port. There was little resistance as the Republic's flag was raised on the beach of Motril. Kléber was ecstatic, sending an optimistic report to the Ministry of National Defence. The following days were quiet in Motril, bloody in Torreblanca, and desperate in Alcolea. In Alcolea and Torreblanca, the struggles in the streets proved indecisive. Antonio Escobar Huertas was still very much stuck straddling the outskirts of Alcolea whilst Luis Barceló's soldiers found that their few breakthroughs out of the town limits were turned back within hours.

General Kléber writing his report from Motril.

On the 21st October, another report came in to Valencia. Indalecio Prieto was said to have demanded to see the entire General Staff as soon as the news reached him. In the early hours of the morning of the 21st October, Toledo had fallen to the Nationalists.

The ruins of Toledo that Franco would inherit.

***

[1] Though it will not stand forever.

[2] In OTL, Teruel was the last chance for a Republican military victory. The battle there was particularly gruesome and dealt a huge blow to the People's Republican Army. The Republic will dodge that bullet ITTL.

[3] In OTL, the Army of Andalusia would be formed a month or so later during a huge reorganization of the Republic's armed forces.

[4] Casado was an anti-communist, and was thus viewed with suspicion by many in the Republic's army and government.

[5] As it was in OTL. Though, the plans amounted to nothing.

[6] Queipo de Llano practically ruled Andalusia as his own personal kingdom. He built up an astounding cult of personality around himself from his post in Seville. When Franco first visited the general in late 1936, he found posters, mirrors and even ashtrays bearing Queipo de Llano's face on them. Although, the greatest affront to Franco was the Republican flag that Queipo de Llano still flew and believed in.

Last edited:

I've always been interested in a Red Spain. Although how it survives Barbarossa...

Those Pyrenees aren't really made for Blitzkrieg, are they?

Share: