I agree with this mostly. Where I disagree is that I don't think this would necessarily dissuade congress from pursuing projects like this if they have extra billions sitting around. I mean even today theres a large group of people (seemingly including the current administration) that basically fantasize over passenger rail in the US despite the fact it would be a complete waste of time and money that wouldn't get used anywhere near enough to justify its existence. Back in the 60s before the complete and total collapse of passenger rail I don't think its unreasonable to say congress would look to invest in some form of expanded network if they had a lot of extra money sitting around. Its rather contingent on who would be in power going forward though. A GOP admin in the 60s TTL would likely just return the surplus to the taxpayers via tax cuts, while a Democratic admin would probably look towards these types of projects and other programs.As soon as the railroads lose the mail contracts for moving mail to the airlines, the fuze is lit for passenger rail collapse in the USA.

Moving mail was the most profitable thing they moved, followed by express freight, then regular freight, and then bulk commodities, with passenger operations losing money except in a few areas, like the NE Corridor.

Mac in place of Ike won't change this.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Patton in Korea/MacArthur in the White House

- Thread starter BiteNibbleChomp

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

marathag

Banned

The people there don't know that it's extra, with no way to peer into our realityI agree with this mostly. Where I disagree is that I don't think this would necessarily dissuade congress from pursuing projects like this if they have extra billions sitting around. I mean even today theres a large group of people (seemingly including the current administration) that basically fantasize over passenger rail in the US despite the fact it would be a complete waste of time and money that wouldn't get used anywhere near enough to justify its existence. Back in the 60s before the complete and total collapse of passenger rail I don't think its unreasonable to say congress would look to invest in some form of expanded network if they had a lot of extra money sitting around. Its rather contingent on who would be in power going forward though. A GOP admin in the 60s TTL would likely just return the surplus to the taxpayers via tax cuts, while a Democratic admin would probably look towards these types of projects and other programs.

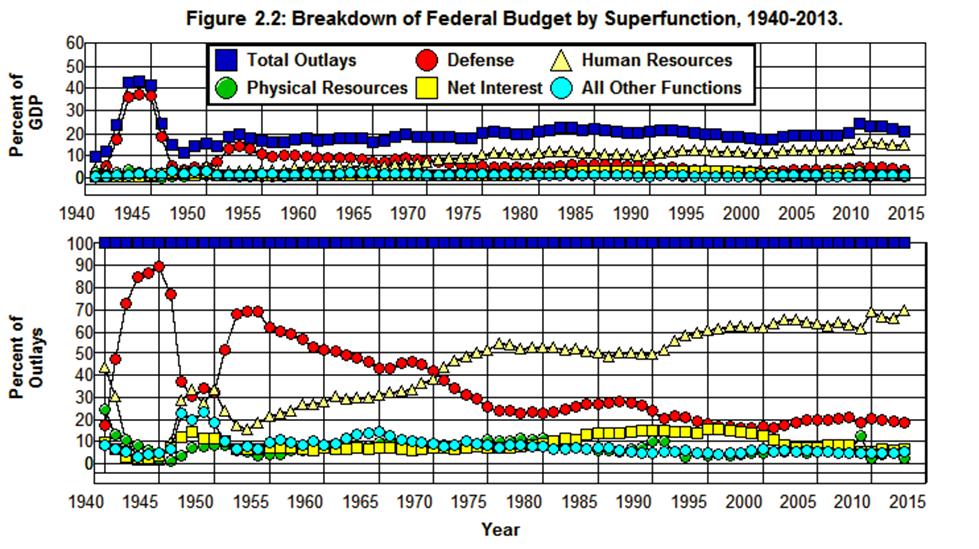

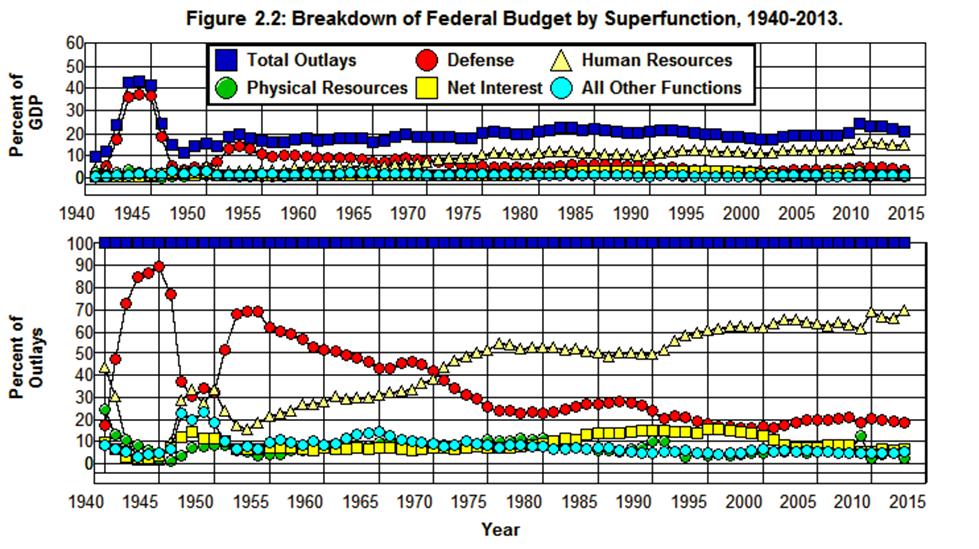

This ATL, Korea didn't cost so much, but are still paying off WWII, that dwarfed it.

and it's likely that the Defense outlay would be less, but that doesn't mean that same level of spending is bumped up for other things

Im assuming that the decrease in defense spending will happen on a much greater scale (more like OTL detente) because of a more relaxed Cold War (reunified Germany, no Vietnam), which would mean that either that money would be quickly spent elsewhere or there would be a large surplus. Surpluses don't last because theres no political incentive for them to last. People ITTL would see the surplus without needing to be able to look into our TL. It'd either get spent through new programs and increased spending or through tax cuts.The people there don't know that it's extra, with no way to peer into our reality

View attachment 659899

This ATL, Korea didn't cost so much, but are still paying off WWII, that dwarfed it.

and it's likely that the Defense outlay would be less, but that doesn't mean that same level of spending is bumped up for other things

Part VI, Chapter 46

CHAPTER 46

On July 27th, 1956, Dwight Eisenhower became the last person in the government to offer an objection to the decision of President Douglas MacArthur. At this late stage in his Presidency, few would have dared consider it. The reassignment of John Foster Dulles had set the tone for MacArthur’s cabinet, the purge of Hoover and the FBI had confirmed it. MacArthur wanted a staff that would carry out his orders without question, and one by one his cabinet members found themselves so entranced by MacArthur’s greatness that they became his willing lackeys, or they were replaced with someone who would.

But when Eisenhower heard the news that Egyptian President Nasser was nationalising the Suez Canal, he felt he had no other choice. He knew MacArthur better than anyone else, possibly better than MacArthur even knew himself. He had known MacArthur for twenty-five years, been his military aide for seven and his UN Ambassador for nearly four. Like MacArthur, he had risen through the ranks to become a theatre commander, he had been the head of an occupation of a defeated country, and had even run for President, and never before had he been so sure that MacArthur was about to make a mistake.

Ever since he met Nasser at the Bandung Conference in 1955, MacArthur had grown increasingly suspicious of the Egyptian leader. He perceived Nasser’s open willingness to play the Americans and Soviets off each other as humiliating, and Nasser’s aggressive nationalist rhetoric as dangerous. There was also the possibility that Nasser was working with, or under the influence of, communist agents: the unification of Germany had put an end to the ideology’s expansion in Europe, and the development of America’s allies were restricting its spread in Asia, so the last axis of advance would be Africa and the Middle East.

Iran was just the first step, and nothing made that more obvious than the events of the previous three days: Reza Radmanesh’s regime, never popular with the people, had fallen into a state of near-civil war after a belated election was rigged and conservatives resisted the creation of a centrally planned economy. Radmanesh lacked the troops to put down the revolts on his own, and had found himself forced to ask Malenkov for help. A quarter of a million Red Army troops were now marching into Iran. Egypt, the crossroads of the world, could be next.

MacArthur had scarcely received the news that Nasser was nationalising the canal when the White House received a call from Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and for one of the rare times in his entire term, the President answered it himself. Churchill said that he favoured immediate and decisive action to reclaim the canal, but only if such an action had MacArthur’s approval.

MacArthur needed no convincing. The canal was a vital trade route, with half of Europe’s oil passing through it. As long as the canal was in Nasser’s hands, he held a knife at the throat of America’s strongest allies. Nasser had long proven that he could not be trusted. Nor was MacArthur willing to consider the possibility of backing down. Drew Pearson had criticised his administration repeatedly for any sign of weakness: the loss of Iran, the loss of Vietnam, the abandonment of West Germany, even his inability to repeal Taft-Hartley. MacArthur would not allow his legacy to be one of weakness. He would not back down. This was the time to thwart the spread of communism into Africa. There was no alternative. Nasser had to go.

Eisenhower was not so convinced. Nasser, he told MacArthur, was not acting as part of any communist plot, but was seizing the canal merely as an act to put an end to the legacy of colonialism in his country. The Egyptian people, and for that matter the rest of the Arab world and probably Africa as well, would not see American intervention as a justified response to the abrogation of the treaty that guaranteed British control of the Canal Zone until 1968. They would see that treaty as having been unfairly forced upon them, enforcing it could only mean a return of the colonial policies. “Doug,” he said, “you have built up considerable goodwill with the people of the Third World, while Malenkov is destroying Russia’s image with his invasion of Iran. This is exactly the opportunity you have spoken of for decades. Don’t waste it all on one of Churchill’s silly schemes. I was dragooned into a few of them in the war, and they never end well.”

MacArthur was certain that the Egyptian people would instead greet him as a liberator upon Nasser’s defeat. He had proven before that he was no coloniser. The Third World knew that it could trust him. Like the Japanese in 1945, once the leadership was removed the people would see him as their friend.

“This is different.” Eisenhower warned. “There’s no Emperor this time, and someone is going to have to lead the country at the end of it all. Four years ago, when Harry Truman was sitting in that chair, and Nasser was about to take power, he faced the same dilemma you do now. He could either tolerate Nasser, who we cannot trust and we do not like, or he could replace him. In Egypt, there’s two alternatives to Nasser and the Army strong enough to take power and hold onto it: the Muslim Brotherhood, and the communists, and they’ve both sworn themselves to our destruction. Nasser might be bad. Your alternatives are worse.”

MacArthur remained as defiant as ever. “Harry Truman made a mistake,” he said.

Eisenhower submitted his resignation the following morning.

***

MacArthur believed that his predecessor had made many mistakes, but one of his gravest had been during the first days of the Korean War. ‘Too late’. Two words that summed up the very history of failure. MacArthur thought back to that grim morning six years earlier, when again he had asked himself “What is the United States’ policy in Asia”. The answer, he had soon realised, was the appalling fact that Truman’s administration had no policy in Asia. Truman had delayed too long, and his delays invited the communists to strike at South Korea. Only his own bold and decisive action - the rapid deployment of Task Force Smith as an initial show of force, and then the transport of whole divisions from Japan - had prevented what had looked like certain, ignominious defeat.

MacArthur would not repeat Truman’s mistakes. His policy on the Egyptian matter would not be left uncertain, or subject to bureaucratic delays and the unclear language of UN resolutions. Before Nasser seized it, the Suez Canal had been mostly owned by both the British and the French. Churchill was already informed, and was just as committed to swift action as he was, but three powers in the coalition would be better than two. Ned Almond was ordered to ring De Gaulle and find out the French position on the matter.

Much to MacArthur’s surprise, De Gaulle wanted no part of the intervention. After the disaster in Algeria, France was seeking to extricate itself from military commitments in North Africa and bring peace to the region, not get involved in another colonial mess. When Almond, in a final act of persuasion, urged De Gaulle to consider the intervention an act of solidarity on behalf of the Western alliance, the French leader responded with an impressive tirade:

“What did that solidarity mean to Monsieur MacArthur when he trampled all over France’s honour at Glasgow? What did it mean when he ordered us to abandon the fight in Indochina? No! I will not stand for this nonsense! We will not fight in Egypt! France is not your puppet!”

Almond, taken aback, asked the interpreter, “did he actually say that?”

“Actually he shouted it,” the interpreter said.

Despite De Gaulle’s refusal to support the intervention, MacArthur insisted on pushing ahead regardless. Less than an hour after De Gaulle refused to fight, MacArthur ordered twenty-four brand-new B-52 bombers to fly to the Wheelus Air Base in Libya, where they would be ready to bomb Egypt.

Another mistake that Truman had made in the June of 1950 was his failure to seek Congressional approval. By calling Korea a “police action” among other terms that only minimised the severity of the situation, Truman had bypassed that most fundamental tenet of the American government, the voice of the people. The President was no dictator, and Truman’s actions set a dangerous precedent. MacArthur, staring down the barrel of the next war, was determined to reverse that precedent and allow Congress to once again do its duty. He could order the movements of troops, ships and planes in his role as Commander-in-chief, but despite what Truman believed, he could not declare war.

Even as the bombers lifted off bound for Libya, MacArthur still hoped that war could be avoided. He knew the difficulties that soldiers endured on campaign, he had seen young men give their lives, he knew the terrible toll that battle wrought. Sometimes the price had to be paid, and a short war with Egypt would be a relatively small price to avoid the communist subjugation of all of Africa. However, sometimes it did not. Nasser backing down, in the same manner that Red China had two years prior, would be preferable to the deaths of hundreds of soldiers, and would thwart communist plans almost as effectively as a war would. Although he doubted it was possible, MacArthur hoped for a peaceful resolution to the Suez Crisis: when he called an emergency meeting of Congress, he asked not for an immediate declaration of war, but for an ultimatum to be sent to Cairo. Nasser could return the canal to its previous owners, or he would face war with three of the strongest nations in the world.

Communism might have been a worldwide threat, but MacArthur had always seen a distinction between the foreign policies of individual communist states, and the cornerstone of his own diplomatic efforts had always been his exploitation of the divisions between them. When he had confronted Red China over Quemoy, he had done so confident that the Soviets would not risk nuclear war over a nation whose leadership ceaselessly accused it of ideological deviance, and had been proven right. The same would hold true in his handling of the Suez Crisis. China had already been cowed, but he still had to separate Egypt from the Soviet Union, and the key to doing so lay in Iran. The Soviet Union shared few borders with MacArthur and his allies, and had no way to send aid directly to Egypt without going through Turkey or British Iraq, so MacArthur doubted they would go to war directly, but a Soviet condemnation of the intervention in Egypt would still be politically damaging to the Allies. Yet it had been Malenkov, not MacArthur, who had first moved troops into the Middle East, when he answered Radmanesh’s call for assistance. To ensure Malenkov stayed out, MacArthur sent a secret message to his Soviet counterpart: the United States would stay silent about the tanks rolling down the streets of Tehran if the Soviet Union stayed silent on Egypt.

If war came, Nasser would be forced to fight alone.

***

Keeping his own side united was just as important as keeping his enemies divided, but if anything it proved to be more difficult. With De Gaulle out of the picture, creating a unified plan with the British would be absolutely essential. Willoughby’s estimates, while describing the Egyptian Army as a “paperweight” that was incapable of offensive action and riddled with corruption, put its strength at 150,000 men. Woeful underestimate as it was, a force of that size was more than large enough to be dangerous. Sending in units regiment by regiment, as he had done in those early desperate days in Korea, would be inviting disaster. The American and British general staffs were ordered to develop a plan over the phone and the teleprinter. MacArthur would fly to London.

When he arrived on July 31st, he was presented with Operation Musketeer. Musketeer posited a paratrooper force (predominantly British troops operating out of Cyprus) be landed at Port Said, at the northern end of the Suez Canal. Once Port Said had been captured, it would be used to unload the main body of the invasion force - around 35,000 British and 100,000 Americans (currently based in France), which would overrun the canal zone. Bombers based in Malta, Crete and Cyprus (the latter of which having recently been ceded to Greece in return for permanent basing rights), would provide air support that would paralyse Nasser’s army and prevent them from interfering with the operation. If all went well, the recapture of the canal would be enough to bring about Nasser’s overthrow.

MacArthur thought that idea too optimistic. His father hadn’t beaten Aguinaldo merely by winning a battle: it had taken the capture of the revolutionary to bring an end to the fighting in the Philippines. Kim Il-sung hadn’t surrendered following the fall of Pyongyang: he had hidden out in a mountain cave, then escaped across the Yalu and ended up in Moscow where he had likely been shot by Stalin. Nasser wouldn’t be deposed unless the Allies deposed him. The target couldn’t be the canal. That would be useless as long as the war was on anyway. It had to be Cairo, and Nasser.

MacArthur’s alternative proposal suggested that the full weight of the Allied armies be used in a massive amphibious offensive that would land at Alexandria and then march down the Nile. While Churchill was supportive, his declining health ensured that his position at the conference, and indeed as prime minister, was largely ceremonial. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, Churchill’s deputy and the power behind the throne, was adamantly opposed. Alexandria would be a waste of time and a waste of lives, the latter especially important if the war was to be the quick affair everyone hoped it would be: with National Service finished in Britain and American reinforcements needing a month to cross the Atlantic, the Allies would be short on manpower. Eden refused to allow British troops to be used at Alexandria, but while MacArthur had given overall command of the war to British General Charles Keightley (owing to the Canal Zone’s previous status as a British possession), the Americans were contributing the overwhelming majority of the troops, and so he insisted on having the final say on where they were committed.

The impasse between the two stubborn leaders was only resolved when a third nation joined the coalition: Israel. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, fearing that the Arab League would eventually come together and attempt to wipe his nation off the map as they had tried in 1948, believed that the Suez Crisis presented the perfect opportunity for a pre-emptive strike to secure Israel’s western border. Though he would have preferred to move with the help of his closest ally, France, Ben-Gurion knew he might not have another chance.

Israel greatly changed the strategic balance: Ben-Gurion offered 175,000 troops, which would more than double the allies’ strength currently marked for action against Egypt, and an attack in the Sinai would prevent Egyptian troops there from attacking the eastern flank of the column that would capture the canal. Port Said, with Israeli support nearby, had suddenly become the far less risky plan. Under the new circumstances, Churchill gave what should have been the deciding vote in favour of the Port Said plan.

MacArthur, fixated on Alexandria, refused to budge. If his allies would not land their forces there, then Alexandria would be a wholly American affair. Musketeer was rewritten as a two-pronged attack: landings at both Port Said and Alexandria, followed by a pincer movement on Cairo. Israel’s forces would provide a diversion, and would stop ten miles east of the canal.

Three weeks after it was issued, the ultimatum to Nasser expired, dismissed as a bluff by the Egyptian leadership. On August 17th, the order was given. The Egyptian War, “the encore of an era”, had begun.

- BNC

On July 27th, 1956, Dwight Eisenhower became the last person in the government to offer an objection to the decision of President Douglas MacArthur. At this late stage in his Presidency, few would have dared consider it. The reassignment of John Foster Dulles had set the tone for MacArthur’s cabinet, the purge of Hoover and the FBI had confirmed it. MacArthur wanted a staff that would carry out his orders without question, and one by one his cabinet members found themselves so entranced by MacArthur’s greatness that they became his willing lackeys, or they were replaced with someone who would.

But when Eisenhower heard the news that Egyptian President Nasser was nationalising the Suez Canal, he felt he had no other choice. He knew MacArthur better than anyone else, possibly better than MacArthur even knew himself. He had known MacArthur for twenty-five years, been his military aide for seven and his UN Ambassador for nearly four. Like MacArthur, he had risen through the ranks to become a theatre commander, he had been the head of an occupation of a defeated country, and had even run for President, and never before had he been so sure that MacArthur was about to make a mistake.

Ever since he met Nasser at the Bandung Conference in 1955, MacArthur had grown increasingly suspicious of the Egyptian leader. He perceived Nasser’s open willingness to play the Americans and Soviets off each other as humiliating, and Nasser’s aggressive nationalist rhetoric as dangerous. There was also the possibility that Nasser was working with, or under the influence of, communist agents: the unification of Germany had put an end to the ideology’s expansion in Europe, and the development of America’s allies were restricting its spread in Asia, so the last axis of advance would be Africa and the Middle East.

Iran was just the first step, and nothing made that more obvious than the events of the previous three days: Reza Radmanesh’s regime, never popular with the people, had fallen into a state of near-civil war after a belated election was rigged and conservatives resisted the creation of a centrally planned economy. Radmanesh lacked the troops to put down the revolts on his own, and had found himself forced to ask Malenkov for help. A quarter of a million Red Army troops were now marching into Iran. Egypt, the crossroads of the world, could be next.

MacArthur had scarcely received the news that Nasser was nationalising the canal when the White House received a call from Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and for one of the rare times in his entire term, the President answered it himself. Churchill said that he favoured immediate and decisive action to reclaim the canal, but only if such an action had MacArthur’s approval.

MacArthur needed no convincing. The canal was a vital trade route, with half of Europe’s oil passing through it. As long as the canal was in Nasser’s hands, he held a knife at the throat of America’s strongest allies. Nasser had long proven that he could not be trusted. Nor was MacArthur willing to consider the possibility of backing down. Drew Pearson had criticised his administration repeatedly for any sign of weakness: the loss of Iran, the loss of Vietnam, the abandonment of West Germany, even his inability to repeal Taft-Hartley. MacArthur would not allow his legacy to be one of weakness. He would not back down. This was the time to thwart the spread of communism into Africa. There was no alternative. Nasser had to go.

Eisenhower was not so convinced. Nasser, he told MacArthur, was not acting as part of any communist plot, but was seizing the canal merely as an act to put an end to the legacy of colonialism in his country. The Egyptian people, and for that matter the rest of the Arab world and probably Africa as well, would not see American intervention as a justified response to the abrogation of the treaty that guaranteed British control of the Canal Zone until 1968. They would see that treaty as having been unfairly forced upon them, enforcing it could only mean a return of the colonial policies. “Doug,” he said, “you have built up considerable goodwill with the people of the Third World, while Malenkov is destroying Russia’s image with his invasion of Iran. This is exactly the opportunity you have spoken of for decades. Don’t waste it all on one of Churchill’s silly schemes. I was dragooned into a few of them in the war, and they never end well.”

MacArthur was certain that the Egyptian people would instead greet him as a liberator upon Nasser’s defeat. He had proven before that he was no coloniser. The Third World knew that it could trust him. Like the Japanese in 1945, once the leadership was removed the people would see him as their friend.

“This is different.” Eisenhower warned. “There’s no Emperor this time, and someone is going to have to lead the country at the end of it all. Four years ago, when Harry Truman was sitting in that chair, and Nasser was about to take power, he faced the same dilemma you do now. He could either tolerate Nasser, who we cannot trust and we do not like, or he could replace him. In Egypt, there’s two alternatives to Nasser and the Army strong enough to take power and hold onto it: the Muslim Brotherhood, and the communists, and they’ve both sworn themselves to our destruction. Nasser might be bad. Your alternatives are worse.”

MacArthur remained as defiant as ever. “Harry Truman made a mistake,” he said.

Eisenhower submitted his resignation the following morning.

***

MacArthur believed that his predecessor had made many mistakes, but one of his gravest had been during the first days of the Korean War. ‘Too late’. Two words that summed up the very history of failure. MacArthur thought back to that grim morning six years earlier, when again he had asked himself “What is the United States’ policy in Asia”. The answer, he had soon realised, was the appalling fact that Truman’s administration had no policy in Asia. Truman had delayed too long, and his delays invited the communists to strike at South Korea. Only his own bold and decisive action - the rapid deployment of Task Force Smith as an initial show of force, and then the transport of whole divisions from Japan - had prevented what had looked like certain, ignominious defeat.

MacArthur would not repeat Truman’s mistakes. His policy on the Egyptian matter would not be left uncertain, or subject to bureaucratic delays and the unclear language of UN resolutions. Before Nasser seized it, the Suez Canal had been mostly owned by both the British and the French. Churchill was already informed, and was just as committed to swift action as he was, but three powers in the coalition would be better than two. Ned Almond was ordered to ring De Gaulle and find out the French position on the matter.

Much to MacArthur’s surprise, De Gaulle wanted no part of the intervention. After the disaster in Algeria, France was seeking to extricate itself from military commitments in North Africa and bring peace to the region, not get involved in another colonial mess. When Almond, in a final act of persuasion, urged De Gaulle to consider the intervention an act of solidarity on behalf of the Western alliance, the French leader responded with an impressive tirade:

“What did that solidarity mean to Monsieur MacArthur when he trampled all over France’s honour at Glasgow? What did it mean when he ordered us to abandon the fight in Indochina? No! I will not stand for this nonsense! We will not fight in Egypt! France is not your puppet!”

Almond, taken aback, asked the interpreter, “did he actually say that?”

“Actually he shouted it,” the interpreter said.

Despite De Gaulle’s refusal to support the intervention, MacArthur insisted on pushing ahead regardless. Less than an hour after De Gaulle refused to fight, MacArthur ordered twenty-four brand-new B-52 bombers to fly to the Wheelus Air Base in Libya, where they would be ready to bomb Egypt.

Another mistake that Truman had made in the June of 1950 was his failure to seek Congressional approval. By calling Korea a “police action” among other terms that only minimised the severity of the situation, Truman had bypassed that most fundamental tenet of the American government, the voice of the people. The President was no dictator, and Truman’s actions set a dangerous precedent. MacArthur, staring down the barrel of the next war, was determined to reverse that precedent and allow Congress to once again do its duty. He could order the movements of troops, ships and planes in his role as Commander-in-chief, but despite what Truman believed, he could not declare war.

Even as the bombers lifted off bound for Libya, MacArthur still hoped that war could be avoided. He knew the difficulties that soldiers endured on campaign, he had seen young men give their lives, he knew the terrible toll that battle wrought. Sometimes the price had to be paid, and a short war with Egypt would be a relatively small price to avoid the communist subjugation of all of Africa. However, sometimes it did not. Nasser backing down, in the same manner that Red China had two years prior, would be preferable to the deaths of hundreds of soldiers, and would thwart communist plans almost as effectively as a war would. Although he doubted it was possible, MacArthur hoped for a peaceful resolution to the Suez Crisis: when he called an emergency meeting of Congress, he asked not for an immediate declaration of war, but for an ultimatum to be sent to Cairo. Nasser could return the canal to its previous owners, or he would face war with three of the strongest nations in the world.

Communism might have been a worldwide threat, but MacArthur had always seen a distinction between the foreign policies of individual communist states, and the cornerstone of his own diplomatic efforts had always been his exploitation of the divisions between them. When he had confronted Red China over Quemoy, he had done so confident that the Soviets would not risk nuclear war over a nation whose leadership ceaselessly accused it of ideological deviance, and had been proven right. The same would hold true in his handling of the Suez Crisis. China had already been cowed, but he still had to separate Egypt from the Soviet Union, and the key to doing so lay in Iran. The Soviet Union shared few borders with MacArthur and his allies, and had no way to send aid directly to Egypt without going through Turkey or British Iraq, so MacArthur doubted they would go to war directly, but a Soviet condemnation of the intervention in Egypt would still be politically damaging to the Allies. Yet it had been Malenkov, not MacArthur, who had first moved troops into the Middle East, when he answered Radmanesh’s call for assistance. To ensure Malenkov stayed out, MacArthur sent a secret message to his Soviet counterpart: the United States would stay silent about the tanks rolling down the streets of Tehran if the Soviet Union stayed silent on Egypt.

If war came, Nasser would be forced to fight alone.

***

Keeping his own side united was just as important as keeping his enemies divided, but if anything it proved to be more difficult. With De Gaulle out of the picture, creating a unified plan with the British would be absolutely essential. Willoughby’s estimates, while describing the Egyptian Army as a “paperweight” that was incapable of offensive action and riddled with corruption, put its strength at 150,000 men. Woeful underestimate as it was, a force of that size was more than large enough to be dangerous. Sending in units regiment by regiment, as he had done in those early desperate days in Korea, would be inviting disaster. The American and British general staffs were ordered to develop a plan over the phone and the teleprinter. MacArthur would fly to London.

When he arrived on July 31st, he was presented with Operation Musketeer. Musketeer posited a paratrooper force (predominantly British troops operating out of Cyprus) be landed at Port Said, at the northern end of the Suez Canal. Once Port Said had been captured, it would be used to unload the main body of the invasion force - around 35,000 British and 100,000 Americans (currently based in France), which would overrun the canal zone. Bombers based in Malta, Crete and Cyprus (the latter of which having recently been ceded to Greece in return for permanent basing rights), would provide air support that would paralyse Nasser’s army and prevent them from interfering with the operation. If all went well, the recapture of the canal would be enough to bring about Nasser’s overthrow.

MacArthur thought that idea too optimistic. His father hadn’t beaten Aguinaldo merely by winning a battle: it had taken the capture of the revolutionary to bring an end to the fighting in the Philippines. Kim Il-sung hadn’t surrendered following the fall of Pyongyang: he had hidden out in a mountain cave, then escaped across the Yalu and ended up in Moscow where he had likely been shot by Stalin. Nasser wouldn’t be deposed unless the Allies deposed him. The target couldn’t be the canal. That would be useless as long as the war was on anyway. It had to be Cairo, and Nasser.

MacArthur’s alternative proposal suggested that the full weight of the Allied armies be used in a massive amphibious offensive that would land at Alexandria and then march down the Nile. While Churchill was supportive, his declining health ensured that his position at the conference, and indeed as prime minister, was largely ceremonial. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, Churchill’s deputy and the power behind the throne, was adamantly opposed. Alexandria would be a waste of time and a waste of lives, the latter especially important if the war was to be the quick affair everyone hoped it would be: with National Service finished in Britain and American reinforcements needing a month to cross the Atlantic, the Allies would be short on manpower. Eden refused to allow British troops to be used at Alexandria, but while MacArthur had given overall command of the war to British General Charles Keightley (owing to the Canal Zone’s previous status as a British possession), the Americans were contributing the overwhelming majority of the troops, and so he insisted on having the final say on where they were committed.

The impasse between the two stubborn leaders was only resolved when a third nation joined the coalition: Israel. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, fearing that the Arab League would eventually come together and attempt to wipe his nation off the map as they had tried in 1948, believed that the Suez Crisis presented the perfect opportunity for a pre-emptive strike to secure Israel’s western border. Though he would have preferred to move with the help of his closest ally, France, Ben-Gurion knew he might not have another chance.

Israel greatly changed the strategic balance: Ben-Gurion offered 175,000 troops, which would more than double the allies’ strength currently marked for action against Egypt, and an attack in the Sinai would prevent Egyptian troops there from attacking the eastern flank of the column that would capture the canal. Port Said, with Israeli support nearby, had suddenly become the far less risky plan. Under the new circumstances, Churchill gave what should have been the deciding vote in favour of the Port Said plan.

MacArthur, fixated on Alexandria, refused to budge. If his allies would not land their forces there, then Alexandria would be a wholly American affair. Musketeer was rewritten as a two-pronged attack: landings at both Port Said and Alexandria, followed by a pincer movement on Cairo. Israel’s forces would provide a diversion, and would stop ten miles east of the canal.

Three weeks after it was issued, the ultimatum to Nasser expired, dismissed as a bluff by the Egyptian leadership. On August 17th, the order was given. The Egyptian War, “the encore of an era”, had begun.

- BNC

Last edited:

If they win will faud still be reinstated under a Regent? Maybe Sadat coukd be spared.

Omg it's happening! Everyone stay calm! Nice to see MacArthur and De Gaulle meeting. I have to say its quite refreshing to see a President that isn't seeking to bypass Congress for a war resolution. As you mentioned Truman did it in Korea with his "police action" and LBJ pretty much had a free hand to do whatever in Vietnam as did Nixon

Last edited:

So after removing Nasser, His Majesty's plan is to put Egypt in a military administration and bring democracy? The British and the French must be having an heart attack looking at the costs.

I thought MacArthur would better judge that involving Israel will end all goodwill in the Arab World, seeking some silent support or looking the other way by some other Arab states like Iraq, Jordan and Morocco might be a good idea.

Stopping the communists in Africa means something for the Portuguese right?

Btw how is De Gaulle in charge so soon?

I thought MacArthur would better judge that involving Israel will end all goodwill in the Arab World, seeking some silent support or looking the other way by some other Arab states like Iraq, Jordan and Morocco might be a good idea.

Stopping the communists in Africa means something for the Portuguese right?

Btw how is De Gaulle in charge so soon?

There are two options that'll happen with this. Either Ike is right and Mac blows US goodwill with the 3rd world and either the Muslim Brotherhood or Communists take over once this is done or Mac ends up pulling out a miracle and successfully gets a regime change into an actual democracy, potentially headed by a constitutional monarchy under Faud II.

Or we end up with a split Egypt with Faud holding onto a rump state in the Sinai by only his fingernails and western backing while the rest of the country is ruled by the MB or Commies.There are two options that'll happen with this. Either Ike is right and Mac blows US goodwill with the 3rd world and either the Muslim Brotherhood or Communists take over once this is done or Mac ends up pulling out a miracle and successfully gets a regime change into an actual democracy, potentially headed by a constitutional monarchy under Faud II.

CHAPTER 46

><

MacArthur responded by ordering twenty-four brand-new B-52 bombers to fly to bases in France. There, they would be able to strike Egypt and return without refueling.

Why France? We already have a 'forward base' in the area? (Wheelus was the regional MATS hub as well) we also have a base in Morocco, and I'm pretty sure some agreements with some other areas. I can see staying out of Algiers but France is a bit far away.

Randy

Well, while 'd seems probable that the airborne assault to the channel and even if seems possible that TTL amphibian one to Alexandria, would meet, with similar (military) success to IOT. And if, as seem probable that Nasser would decide to resist and fight against the Western invasion...There are two options that'll happen with this. Either Ike is right and Mac blows US goodwill with the 3rd world and either the Muslim Brotherhood or Communists take over once this is done or Mac ends up pulling out a miracle and successfully gets a regime change into an actual democracy, potentially headed by a constitutional monarchy under Faud II.

Then, I would say that would have been very high chances that the march Nile down to the Cairo and in the city itself, would have turned in ITTL equivalents, for the US Army/Marines, to the OTL Battles of Huế City and/or (2d) of Fallujah.

There's also a "Middle Case" option: Mac blows some but not all US goodwill with the 3rd world. Either the Muslim Brotherhood or Communists or a different Army faction take over and the new regime is hostile to the US. But the US has also set a precedent that while the US does support de-colonization it does not support nationalizing foreign assets.There are two options that'll happen with this. Either Ike is right and Mac blows US goodwill with the 3rd world and either the Muslim Brotherhood or Communists take over once this is done or Mac ends up pulling out a miracle and successfully gets a regime change into an actual democracy, potentially headed by a constitutional monarchy under Faud II.

And with the Canal not under Egyptian control aka not under the control of someone who might shut it down at a moments notice and therefore the possibility of the absence of the canal passage has to be factored into international politics whether it's open or not the Western World can afford to lean on South Africa much earlier than in OTL.

Last edited:

marathag

Banned

Hue had RoEs that limited firepower for most of the campaign, and Fallujah had similar RoEs, along with manpower limits as well as firepower.Then, I would say that would have been very high chances that the march Nile down to the Cairo and in the city itself, would have turned in ITTL equivalents, for the US Army/Marines, to the OTL Battles of Huế City and/or (2d) of Fallujah.

That isn't the case with Mac, who would be in Korean War mode, where it was the norm to destroy the place in order to save it

LBJ may have been fine with using B-52s to bomb suspected truck parks along the Trail, but certainly not towns, but Mac wouldn't shy away from what was done in Korea, using B-29s to level cities, just as had been done in Japan.

People don't realize how wrecked Korea was, both North and South, from unrestricted bombing during that 'Police Action'

But, would, the US, be able or even willing to use the B52's? When their possible targets would be fighting in close combat with the American troops? Also, even if Mac would be willing to ignoring the more than probable thousands to millions of civilian casualties that such strategy would imply, but, at least I'm missing something, but the mission encomendad to the US troops, would be very similar to IOTL, president Bush invasion of Panama, against Noriega, but a lot bloodier.That isn't the case with Mac, who would be in Korean War mode, where it was the norm to destroy the place in order to save it

LBJ may have been fine with using B-52s to bomb suspected truck parks along the Trail, but Mac wouldn't shy away from what was done in Korea, using B-29s to level cities, just as had been done in Japan.

People don't realize how wrecked Korea was, both North and South, from unrestricted bombing during that 'Police Action'

I.e. overthrowing the Egyptian leader bringing down the Nasser regime through his capture by the American troops. Given that I don't think that the above mentioned Korean war example, would be adequate for TTL Mac administration, Great Britain and France plus Israel, strategic goals.

marathag

Banned

My Uncle, during his 1st tour in Vietnam, said that the danger-close ArcLight drop was the scariest, yet most impressive destructive event he ever witnessed from his time in Korea, or ever. 16" from New Jersey seemed lacking, after that.When their possible targets would be fighting in close combat with the American troops?

A partial map grid, near instantly moonscaped.

Complete silence, excepting the mortar and small arms fire from the VC there, then 30 seconds of actual Hell on Earth, then real silence, other than the ringing in his ears from the overpressure.

I have troubles seeing de Gaulle having France getting on board with the intervention.Ned Almond was ordered to ring De Gaulle and find out the French position on the matter. De Gaulle, concerned by how Nasser’s nationalisation of the canal would impact the situation in Algeria, soon replied that France would be willing to commit military forces to an operation in the Suez region.

On one hand, Guy Mollet was stuck fighting to keep Algeria a French territory, and Egypt, the parangon of Arab nationalism and the FLN's big brother, would have been Paris' natural enemy, so the decision to go into Egypt along the British and Israel was a natural one. On the other hand, de Gaulle was firmly decided on getting out of the Algerian mess, so it would not be coherent on his part to getting into another mess, all the more as I see him having pretty much the same analysis as Eisenhower had in the update. If one has to compare the situations of OTL and TTL, it's like when the Americans got into Vietnam, and de Gaulle declared his opposition to it (and recognized China's communist government in 65). So, Mollet sending troops to Egypt was logical, de Gaulle doing the same is incoherent.

The best MacArthur could get from de Gaulle is neutrality I think. But I see equally possible, and perhaps even likely, that de Gaulle being de Gaulle, if he is in serious disagreement enough like Eisenhower was, that he publicly opposes the invasion in a way not unlike Chirac's no to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 ("and it's an old country, France" , Villepin speech could have been spoken by de Gaulle, and Chirac was himself the last president of the gaullist brand).

A further motive he might have in doing so is that he was seeking a negotiated withdrawal in Algeria, and if France participated or assented to the invasion of Egypt, chances at a peaceful end of the war like he got IOTL in 1962 Evian accords would go up in smoke, a disaster for de Gaulle policies.

Last edited:

If they win will faud still be reinstated under a Regent? Maybe Sadat coukd be spared.

I'll mention the post-Nasser plans in the coming updatesOr we end up with a split Egypt with Faud holding onto a rump state in the Sinai by only his fingernails and western backing while the rest of the country is ruled by the MB or Commies.

That's pretty nice but when did De Gaulle became leader of France ? Because OTL he wasn't between 1946 and 1958

He came to power at the start of Chapter 45, ie about two months before Nasser seized the canal.Btw how is De Gaulle in charge so soon?

Explanation is pretty much "withdrawal from Vietnam prompts an earlier start to the fighting in Algeria as the rebels sense weakness in Paris", then the war following a similar (or slightly less successful for France) path to OTL. Butterflies take care of the discrepancies.

Mac wasn't as good a judge of diplomatic matters as he thought he was. In Korea, he somehow thought that getting a heap of troops from Chiang was a good idea (this being before the PRC got involved)... think it follows he'd do the same in Israel.I thought MacArthur would better judge that involving Israel will end all goodwill in the Arab World, seeking some silent support or looking the other way by some other Arab states like Iraq, Jordan and Morocco might be a good idea.

Because I hadn't heard of Wheelus until now and I wasn't sure that any closer bases than France were B-52 capable in 1956. I'll change it in the update once I get a chanceWhy France? We already have a 'forward base' in the area? (Wheelus was the regional MATS hub as well) we also have a base in Morocco, and I'm pretty sure some agreements with some other areas. I can see staying out of Algiers but France is a bit far away.

Randy

Mac would be plenty willing to use the B-52s, although I'd imagine the Canberras or something get the close support jobs while the B-52s are used on more distant targets. Mission creep was kinda the rule for him (with the logic of "we can rebuild it later and they will thank us for it")But, would, the US, be able or even willing to use the B52's? When their possible targets would be fighting in close combat with the American troops? Also, even if Mac would be willing to ignoring the more than probable thousands to millions of civilian casualties that such strategy would imply, but, at least I'm missing something, but the mission encomendad to the US troops, would be very similar to IOTL, president Bush invasion of Panama, against Noriega, but a lot bloodier.

I.e. overthrowing the Egyptian leader bringing down the Nasser regime through his capture by the American troops. Given that I don't think that the above mentioned Korean war example, would be adequate for TTL Mac administration, Great Britain and France plus Israel, strategic goals.

All good pointsI have troubles seeing de Gaulle having France getting on board with the intervention.

On one hand, Guy Mollet was stuck fighting to keep Algeria a French territory, and Egypt, the parangon of Arab nationalism and the FLN's big brother, would have been Paris' natural enemy, so the decision to go into Egypt along the British and Israel was a natural one. On the other hand, de Gaulle was firmly decided on getting out of the Algerian mess, so it would not be coherent on his part to getting into another mess, all the more as I see him having pretty much the same analysis as Eisenhower had in the update. If one has to compare the situations of OTL and TTL, it's like when the Americans got into Vietnam, and de Gaulle declared his opposition to it (and recognized China's communist government in 65). So, Mollet sending troops to Egypt was logical, de Gaulle doing the same is incoherent.

The best MacArthur could get from de Gaulle is neutrality I think. But I see equally possible, and perhaps even likely, that de Gaulle being de Gaulle, if he is in serious disagreement enough like Eisenhower was, that he publicly opposes the invasion in a way not unlike Chirac's no to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 ("and it's an old country, France" , Villepin speech could have been spoken by de Gaulle, and Chirac was himself the last president of the gaullist brand).

A further motive he might have in doing so is that he was seeking a negotiated withdrawal in Algeria, and if France participated or assented to the invasion of Egypt, chances at a peaceful end of the war like he got IOTL in 1962 Evian accords would go up in smoke, a disaster for de Gaulle policies.

I will edit the update accordingly (as well as 47 and 48, which are both almost finished), although I might need a little while

- BNC

Plus, I'll add, de Gaulle might consider the benefit of having, after each three of Soviets, American and British reputation being screwed up in the Middle East, to come out of the fray as the "good guy" in this story. Foreign policy wise, he was keen on pursuing inroads with the Non Aligned Movement, but I think that was essentially because between the Americans and the Soviets, he looked for a space in which France could develop its influence and standing independently, worth the great power he thought it ought to be after the catastrophy of WW2.

Last edited:

That would be fun indeed. I'm not seeing MacArthur reacting well to de Gaulle telling him 'no'. It even made me thinking to this scene from a recent biopic mini series on de Gaulle, where there is a stormy meeting with Churchill. At one point, he says :"You welcomed de Gaulle because he said no to defeat, and today, it's to you and Roosevelt de Gaulle says no!".plus, now that I've thought of it, de Gaulle acting as an Eisenhower-like spoiler to the invasion is probably more fun than what I had planned originally)

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: