You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Of Rajahs and Hornbills: A timeline of Brooke Sarawak

- Thread starter Al-numbers

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far EastEphraim Ben Raphael

Banned

This seems awful political for a lovely little (or not so little) TL about Sarawak and Malaysia.

last admiral

Banned

Kinda what happen when Westboro Baptist Church have oil and own Rome.Kinda sucks that several billion people can't perform their sacred duty without giving money to a regime guilty of several, very un-Islamic crimes.

Down with White Rajah! Nusantara Unification must rise! Arise, Sons of Dirt! Let no mere tradition, border, nor accent divide us! No more shall we beholden to petty kingdoms and imperial's colonies, least foreign power seek to divide us!This seems awful political for a lovely little (or not so little) TL about Sarawak and Malaysia.

Each one of you are a ship! We shall ensure it united under one banner! For i am an admiral(laksamana), and i shall see to it that we succed.

Let "MALAYA" from EU4 and Vic2 became a reality!

Last edited:

Okay, didn't expect this to attract much attention!

Yea... I just wanted to note that I'll be gone for a month or so, in a month or so, and why. Didn't expect this much in responses (thanks, everyone!) though the subject of Islam and politics has added to an idea I've long held of a TL-interlude between four... very different people with very different viewpoints.

....what is EU4 and Vic2?

This seems awful political for a lovely little (or not so little) TL about Sarawak and Malaysia.

Yea... I just wanted to note that I'll be gone for a month or so, in a month or so, and why. Didn't expect this much in responses (thanks, everyone!) though the subject of Islam and politics has added to an idea I've long held of a TL-interlude between four... very different people with very different viewpoints.

Let "MALAYA" from EU4 and Vic2 became a reality!

....what is EU4 and Vic2?

Europa Universalis 4 and Victoria 2

(grand strategy games from Paradox Interactive)

(grand strategy games from Paradox Interactive)

Europa Universalis 4 and Victoria 2

(grand strategy games from Paradox Interactive)

I know. I was pulling ya'll's leg.

Main part of the map has just been finished. Now I'm off to Microsoft Word!

Main part of the map has just been finished. Now I'm off to Microsoft Word!

Oh! Maps!

You are one of the best when it comes to visuals in your TL I think.

Wartime Borneo (3/4): Tribal migration, and an Imam's plan.

Alena Bulan, Ancur: The Bloodshed in the Heart of Borneo, (University of Bandar Charles Press: 1999)

When the Askaris began their campaign of looting and killing across Sabah and northern Sarawak, they also launched one of the most fractious migration episodes in Bornean indigenous history.

The story of migration is often a long process in local historiography; One of the most traditional examples were the journeys of the Iban people from their homeland in the Sentarum Floodplains into the riverlands of south-central Sarawak; a process that took generations and recounted across multiple oral epics that spanned generations. However, the Great War unleased another, much darker, version of this process. The interior Kadazan-Dusun and Orang Sungai peoples of Italian Sabah had long held their grievances while under Italian rule, but the disintegration of colonial order uneased the most fearsome manifestation of Bornean colonialism to date: the marauding Askaris.

Made up of pirates, thieves, and the bottommost sector of tribal society, these groups stoked fear into the hearts of many communities, whom quickly scrambled to defend themselves against the rifle-armed warrior-warlords. When the Askaris began shooting at longhouses to obtain food, many decided to head for the hills. While there are no official numbers of those who fled, most common estimates counted to around ~11,000 to ~14,000 people, mostly of the Kadazan-Dusun subgroup. With north and east Sabah now a conflagration of war, some decided to head west to the Kinabalu Mountains and the safety of the Kingdom of Sarawak. But the mountains were already full of people – the result of over 25 years of slow migration from Italian rule – and the residents there were wary of newcomers from a belligerent nation to boot. Hence, many decided to trek on foot to the next directions: south and southwest.

But south of Italian Sabah lies the Pensiangan highlands of Dutch Borneo, a barely-controlled and barely-explored region of hills and mountains populated mostly by the Murut people. As community after community of Kadazan-Dusun and Orang Sungei refugees began pouring into the region, it wasn’t long before tensions begin to flare. The Muruts quickly accused the arrivals of stealing their lands and rivers, while the arrivals accused the Muruts of being too arrogant to share. By the end of 1905, tribal war flared across Dutch Pensiangan as compromises broke down, overwhelming the meagre Dutch authorities whose presence consisted of little more than isolated river forts scattered sparingly across the lands, each manned by a dozen or so ill-suited men. [1]

As the tribes fought for a stake in the hills and valleys, a fair number began heading further south and west to avoid bloodshed, and even a number of uprooted Murut villages decided to seek better lands. These treks would take many to new grounds, a fair number of which were already populated by existing locals. Some meetings would prove peaceful. Others, conflict. The Great War that had enveloped Borneo’s north is slowly filtering its way across the mountainous rainforests.

Through the long days and cold nights, across months of sun and rain, these treks would take the uprooted Murut, Kadazan-Dusun, and Orang Sungei far deeper into Borneo than ever before, to the deepest heart where mountain spires touch the skies and where trees towered as tall as canyons. And with these landforms came enclosed isolated valleys and vales where the mountainfolk of north-central Borneo call home – the Kayans, the Kelabits, and the many disparate peoples the Kingdom of Sarawak would (later) collectively call as the Orang Ulu: the People of the Headwaters…

********************

Charlie MacDonald, Strange States, Weird Wars, and Bizzare Borders, (weirdworld.postr.com, 2015)

You know how it’s a bit of a cliché to sum up certain parts of world history as “it just got worse?” Well, Brunei wasn’t done with the phrase yet.

Let’s crack open the nuance.

Why did Salahodin became as he did? Because of the injustices he saw and felt in his early life.

Why did he hop to Brunei? He thought the sultanate needed saving.

Why did the sultan of Brunei listened to him? He didn’t want the state to be a pawn. Again.

Why did he agree to Islamize the Bruneian Dayaks?

… Because he didn’t want any more of them to turn traitor and side with Sarawak.

A fair number of them switched sides anyway. Wait. This isn’t nuance. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHH-

Okay, let’s try this again.

-----

Salahodin the imam was… right in diagnosis, wrong in prescription.

For one, he was correct in his assessment of the fickle nature of Bornean power and allegiances. Since time immemorial, Brunei had used the largesse of her empire to cement loyalty amongst regional lords and tribal chieftains. Managing a clientalistic hinterland stretching from West Borneo to the Philippines, this “granting wealth, produce, resources, and sweet loot” worked wonders for the sultanate during her golden era, but it also meant that the web of power was only as strong as the central government’s ability to conduct international trade and reward restless patrons; if trade stagnates, the hinterlands shall form their own states. Once trade plummets, the whole system falls like a spider’s web before rain.

Salahodin was also correct for noticing Brunei’s Dayaks and the key role they played in the state’s partitions. The interior indigenous peoples may be willing to bend their knees to the coasts, but they also have their own issues regarding tribal life that can complicate matters. By a lot. Sarawakian expansion was due to many factors, but it couldn’t have gone as far as it did if it weren’t for the Brooke family’s attention for tribal matters, which factored a lot to regional peace. Because of this, Sarawak’s pacification of the rowdy interior and the diplomatic manoeuvring of their Rajahs regarding local issues pretty much ensured the kingdom an ocean of loyalty and support, which showed pretty clear in the Sabah war theatre.

All this, in a century where Brunei was lax in her tribal policies and where the palace court could not keep up with the pace of a changing world, pretty much doomed the sultanate.

But what Salahodin got wrong was the solution.

You see, he has a…

In his writings that would later form the infamous book, Pandangan Orang Asli – Views on the Original People, he elaborates: “…Several hills and valleys would be entrusted by the negara (state) to the care of such forest peoples for now and forever. They would move, hunt, fish, and farm wherever within, with no fear of being driven-off from these lands, for it would be their Orang Kaya (Rich Men, another term for chieftains) whom would own these soils together. Shura (consultation) would decide their matters and quarrels, replacing warmongering. With this, who among them would side with any conqueror who could offer more than complete freedom?”

Lest things get too rosy, he writes in the very next paragraph: “The areas would be overseen by two representatives of the state, one of which must be an imam, whom would teach the forest peoples the ways of permanent settlement and the one true faith. Should problems arise that are too much for tribal shura, the state should intervene.”

Not so freedom, then.

In the end, the ultimate aim of these tribal trusts was not to maintain traditional lifestyles or even to halt them fraternizing with Sarawak (though that was a big plus for Salahodin). No. The real aim was to turn the Dayaks into Muslim, pro-Brunei auxiliaries. He continues: “The problem of agriculture and livestock shall be remedied by using the farming ways of the Westerners. With such plentiful food, what need would they to fight? Or move? The abandonment of their warlike and jahil (ignorant) ways would be as natural as the setting sun, further opening their hearts to the beautiful faith of Islam. As it should be.”

Not could. Not would. Should. It’s really something to see and hear someone describe a more theocratic version of America’s reservation system and see it as a good thing.

“How can I make this suckier?” Should never be a question asked when dealing with cultural suppression. At all.

Can you see the paradoxes up there? The loopholes? The stupidity? The man didn’t even write anything about, say, how the state will entice these people into reservations! Also, he’s damn clueless on tribal matters regarding war and headhunting, and he’s practically silent on the issue of self-made weapons that, I don’t know, almost every Dayak subgroup can make!? I can say much more on the matter, but I’ll just quip the Ranee Margaret Brooke when she was asked about Salahodin years later: “The man has plentiful words. So do our Dayaks’ parangs.” Parangs, by the way, are jungle-cutting, head-lopping machetes.

Not surprisingly, this plan was veeeeeery controversial. A sizable minority of the court rejected it outright and a few nobles even packed their bags and moved to Sarawak and Malaya to flee from the stupidity of it. Many locals also thought so. I’m not going to even describe exactly how the Brunei court tried to court their Dayak peoples, but it was simply amazing. You can search it yourself on the Net, but to sum up: it involves a slew of imam recruitment from the Sulu Islands, giving them a “preaching pay” for conversions, and enticing Dayaks to move by bribing them with actual free chickens!

And with that, Brunei’s rainforest peoples didn’t stay for long. Some tribes living near Sarawak simply crossed the border, while ones living by the Limbang River moved deeper into the central highlands. 1905 in general saw a slow migration across Brunei as nobles, locals, and Dayaks slowly streamed out to get as faaaaaaaar as they can from Bandar Brunei and her high taxes and plans.

Thing is, the interior of north-central Borneo was in a bit of a tribal… blaze… for the moment. All those uprooted Muruts and Kadazan-Dusuns from Sabah and Pensiangan have themselves uprooted other tribes there to gain land. In fact, almost everyone in north-central Borneo were uprooting each other as a consequence of the Sabahan war theatre and her production of refugees. From Dutch Pensiangan to the Upper Limbang, the interior mountains were aflame with tribal wars. And the Bruneian Dayaks are heading straight for it.

…Now, you might be wondering “I get that we might need to understand this loon’s thinking and all, but aren’t you taking a lot of time to a policy that wouldn’t even work in Borneo today?” In which my answer would be: True, I am taking obscene hours to type this all down. But it is important to notice this, because ol’ Salahodin’s Pandangan Orang Asli became a very widespread book upon printing, with copies spreading across Southeast Asia and beyond.

And for better or worse, the work made its readers think: “Is this what we’re going to do with all our indigenous natives?”

____________________

Notes:

Whew! It is done! If you’re all wondering “but you promised a final conclusion to the whole Brunei-Sarawak-tribal stuff updates!” Calm down. I began work on the final portion two weeks ago, but the resulting work was so long and winding that I decided to split it in two for easier editing and posting. The second half (and conclusion) of the current Sarawak-Brunei-Dayak arc is already finished, but I want to stagger the release by a few days to make some final checks and edits.

EDIT: And to those who feel miffed that I used Tuanku Imam Bonjol as the face of Salahodin, don't hate me!

1. IOTL, the Pensiangan region was nabbed by the British North Borneo Company and was thus administered as a part of Sabah – today the region is now renamed as the Nabawan District. ITTL, the Dutch managed to get a few explorers up there via the Sembakung River during the establishing period of Italian Sabah, and thus claim the area as part of Dutch Borneo. But after that, there isn’t much in the way of Dutch activity or exploitation there, partly because of Pensiangan’s faraway distance from the coast and partly because there are much easier places to exploit than north-central Borneo. As a result, the only presence of Dutch control is a few forts here and there, which were grossly unprepared for any sort of conflict spillover.

Last edited:

Is this referring to people taking a moral reflection on their own policies? Or them taking it for inspiration? Or both, given the "better or worse"?And for better or worse, the work made its readers think: “Is this what we’re going to do with all our indigenous natives?”

Is this referring to people taking a moral reflection on their own policies? Or them taking it for inspiration? Or both, given the "better or worse"?

In that case, I'll be curious to see which people take the former lesson and which ones take the latter.

I love the snarky tone the modern writer uses. The loon deserves it.

I like how you have him come so close to the mark, and then veer off IN THE VERY NEXT PARAGRAPH and totally undo it.

Unfortunately, it rings all too true.

I like how you have him come so close to the mark, and then veer off IN THE VERY NEXT PARAGRAPH and totally undo it.

Unfortunately, it rings all too true.

A Mfecane in Dutch Borneo and the equivalent of various Bedouin settlement schemes in Brunei - what could possibly go wrong? Or maybe, what could possibly not go wrong?

I love the snarky tone the modern writer uses. The loon deserves it.

I like how you have him come so close to the mark, and then veer off IN THE VERY NEXT PARAGRAPH and totally undo it.

Unfortunately, it rings all too true.

The snarky modern writer is fast becoming an endearing figure amongst all my OC's, mostly because I find it really easy to write down complicated and nuanced events when in an informal and snarky tone.

As for Salahodin, an in-TL person would find that he uses a lot of wham paragraphs in his works. The Sulu imam is trying to figure out the same problem all settled states grapple with in confronting nomadic tribes: how to exert control over peoples who can just... walk away from central authority. Unfortunately, he settled on an alt-version of the American reservation system with religious bits added in, which is perhaps the worst kind of solution for a non-industrial state in dealing with armed semi-nomadic groups. Sadly, his kind of thinking would be considered normal and even progressive for the day (try saying to the 1900's American government that tribal lands should be held in trust and state-level relationships should be consultative) and some OTL nations still consider this as the "ideal solution" to indigenous groups.

A Mfecane in Dutch Borneo and the equivalent of various Bedouin settlement schemes in Brunei - what could possibly go wrong? Or maybe, what could possibly not go wrong?

There's a reason why Salahodin will be remembered very badly in TTL Sarawak and Brunei. This is why.

As for the Mfecane, The only good thing about this Bornean version is that the destruction will be more localized and only affect the north and north-central portions of the island. Not that that's good news to anyone in the way.

T O M O R R O W

for real

(but seriously, the next update is long & picture-heavy, and I don't want it on the bottom of this page and make it all scroll-heavy, so please comment away till the next page)

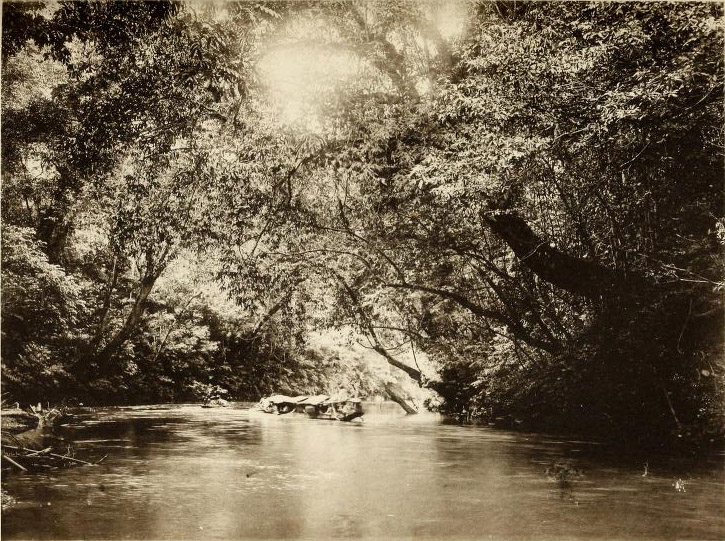

(here's one teaser)

for real

(but seriously, the next update is long & picture-heavy, and I don't want it on the bottom of this page and make it all scroll-heavy, so please comment away till the next page)

(here's one teaser)

Last edited:

Probably some kind of Dayak boat. We'll have to wait to find out affiliation.What is that in the middle of the stream?

Last edited:

Probably some kind of Dayak boat. We'll have to wait to find out affiliation.

Its the Luxembourgers! They've been lulling Borneo into a false sense of security, but now they make their move!

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Share: