You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Of Rajahs and Hornbills: A timeline of Brooke Sarawak

- Thread starter Al-numbers

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Mid-Great War: 1906-1907 Dutch Borneo (Part 3/6)

Ina Manto, Sultans and Chieftains and Controleurs: Borneo Under Late-Dutch Rule (Journal of Postcolonial Studies; 1997)

From the 1890’s till the end of the Great War – and arguably beyond, Dutch Borneo underwent economic, social, and religious changes that were nothing short of seismic.

Some of these changes were brought by local considerations and colonial interests, but others stem from a source of misguided intentions and, ironically, administrative throttling. Starting from January 1901, Batavia and Amsterdam began instituting the Dutch Ethical Policy, which aimed to “uplift the natives of the Indies,” as spoken by the contemporary Governor-General. This would be done through colonial patronization and infrastructural improvements – thus tying the archipelago together whilst (secretly) veering it away from the throes of Islamic reformism [1]. In practice, this would sow the seeds of the region’s tumultuous future, but their short-term effects were no less disruptive.

In a broad sense, the Dayaks of Dutch Borneo now answered to three regional authorities. Massive swathes of land were consolidated under the new Residency Acts to facilitate local administration, with the polestars of government now concentrated on the Residencies of West Borneo (capital: Pontianak), South Borneo (capital: Banjarmasin), and East Borneo (capital: Balikpapan) [2]. Another change – though this would later be finalized in 1910 – was the creation of a separate administrative division for native sultanates and kingdoms, which would be later known as Zelfbesturen. In these parts, some superficial sense of law could be held by local rulers, though they were still constrained by their Dutch overlords and possess no actual power over Chinese and European dwellers.

Other, more intrusive measures were also introduced to better improve indigenous life in the guise of ‘productivity’. The introduction of cash crops was pushed onto local farmholders while Malay and Dayak-held lands were officially legislated, “to never be sold to non-natives”, as a 1903 Pontianak version of the law dictated. Churches and missionary schools mushroomed in downstream towns as foreign priests traversed local waterways to convert curious Dayaks, all while military officials and regional Residents continued persuading the semi-nomadic peoples of the interior to permanently settle down (preferably near the regional capitals where they could be monitored for revolt).

But these questionably ‘enlightened’ policies were far from accepted. In fact, there was a strong counter-notion amongst local bureaucrats of obstructing the Ethical Policy to preserve their own interests, though this was outwardly dressed in the name of preserving local cultures and traditions. Old notions of patronization were strong in the less-developed parts of the Indies, and a fair number of Dutch Bornean civil servants – now further recognized through the same Ethical Policy – actually came from Peranakans and princely families (and thus have an incentive to keep the fruits and power of the Policy to their own class) were also a opposing factor. [3]

Improvement would eventually come to Dutch Borneo, but it would be less so than neighboring Sarawak or Java and much more fought-over.

Royal photo of the Sultan of Kutai Kartanegara ing Martapura, a Malay state in Dutch East Borneo, surrounded by attendants, circa 1909.

Over on the east, colonial intrusion came in another way: petroleum. While knowledge of oil seeps were known in eastern Borneo as early as 1863, it wasn’t until the 1890’s that mass-extraction came to the minds of authorities and Dutch corporations, though some have posited the discovery of oil near the Sarawakian town of Miri in 1898 that finally drove Dutch attention, especially as both Great Britain and Austria-Hungary began to stake their claims on extraction [4]. The first oil well was drilled in 1899 near the town of Balikpapan, which was soon so inundated with wealth that it quickly became the regional capital and the headquarters of several major oil firms.

More was still to come. Further north, the Dutch-controlled Sultanate of Tidung also recorded profitable wells on the island of Tarakan in 1903, sparking another corporate rush. By the end of the Dutch period, Tarakan would yield over five million barrels of raw crude per year, totaling up to one-third of all extracted petroleum in the Dutch East Indies.

Contemporary photograph of a barge carrying materials for the petroleum storage tanks on Tarakan Island, circa 1912.

For a short while, even the language of government communication changed, though local backlash from high and low quickly sunk the measure. The 1903 decision by Batavia to change the regional lingua franca from Malay to Standard Javanese was partly intended to veer the Indies from Islamic reformism, which swirled headily in neighboring, Malay-tonged Aceh and Johor. Instead, Bornean bureaucrats complained of being confused while Malay sultanate families berated their superiors in a rare instance of mass-elite criticism. Though the Javanese Language Policy died a quick death, its effects would kick-start the formation of Dutch Borneo’s modern nationalist circles…

********************

Jalumin Bayogoh, Legendary Icons of Bornean History, (Kenyalang Publishing: 2010)

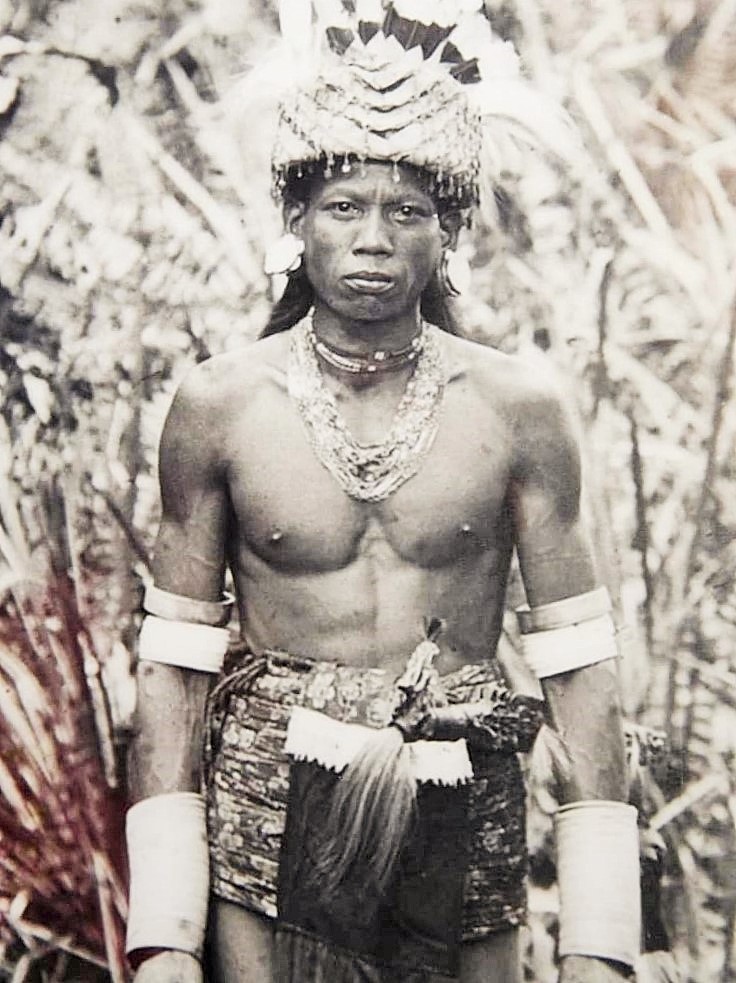

…One famous figure of the Dutch-controlled, yet relatively remote Sentarum Floodplains (though to Sarawak, close-by) was one Penghulu Bantin, a wily Iban chieftain from the Ulu Ai valley of Sarawak. Making a name for himself by conducting tribal wars beyond anyone’s control, he was among a coalition of tribal chiefs whom resisted Brooke rule and it’s imposition of external law during the late 19th century. This animosity was further heightened when his son, Inggol, was killed in 1895 by an allied-Rajah raid on the Ulu Ai valley.

But feeling the pressure of the Brooke government, Bantin decided to relocate deeper inland. Moving further up the valley, the chieftain crossed the border into Dutch Borneo with over 80 following families, settling with Dutch acquiescence in the Sentarum Floodplains.

Despite his knack for raids and wars, Bantin was careful to not ransack any villages inside Dutch Borneo. Not wanting to make another powerful enemy, he maintained good relations with other local tribes, Dutch officials and Chinese merchants, whom quickly saw him as a wary benefactor and bargaining chip. Despite Charles Brooke declaring the Penghulu a true outlaw in 1904 and offering a large bounty for his capture, the Dutch offered him full amnesty should he permanently settle in a controllable area of the Sentarum Floodplains.

However, his fiery disposition would cause far more problems for his new masters than expected, which would impact the region well after Bantin finally called the floodplains his new home… [5]

********************

Kristian anak Minggat, A Summary of 20th century Dutch-Dayak Relations, (Journal of Southeast Asian Studies: 2009)

…It would be something to say, “The Great War landed the Dutch in Borneo in an awkward position.” But the truth eludes simplicity, and describing the horror of the Ancur – the turmoil of Borneo’s indigenous peoples during this period of global conflict – as just an offshoot of Italo-Sarawakian fighting, is too simplistic and reductive a reasoning.

There were already a few noticeable incidents of revolt before the Great War, but the brutal slugfest between the Kingdom of Sarawak and Italian Sabah marked a new and terrifying sign of things to come. As waves of warrior-warlords broke off from Italian control and ravaged the river basins, thousands of Sabahan Dayaks fled south over the mountains into Dutch Borneo and particularly the Pensiangan region, which formed the inland part of the Dutch-controlled Sultanate of Tidung. Many of the refugees belong to the Kadazan-Dusun subgroup whereas most of Pensiangan’s inhabitants were of the Murut ethnic family. Inevitably, conflict ensued.

For the neutral Dutch authorities in faraway Balikpapan, the disturbances were initially seen as a distant nuisance; small spats between tribes that shall blow out once Sarawak captured Italian Sabah. However, the final fall of Sandakan and sudden death of Rajah Charles did nothing to reverse the flow; the fleeing tribes had no wish to return to the horrors of home. One report from a Dutch fort by the Sembakung River described, “…entire villages of newcomers setting up homes by the waterside, sparring with local tribes with the victors taking the local forest as their own.” These uprooted villagers would then move further south, clashing with other tribes and spreading the carnage. The Ancur had begun.

Throughout 1906 and 1907, a slow wave of violence would creep throughout north-central Borneo as displaced peoples fought for control of the mountains and rivers. Longhouses were burnt and streams poisoned in a chaotic melee that would see villages torn apart and the survivors adopting ever more brutal methods of defense. The practice of headhunting – still practiced in some from in these remote regions – exploded into prominence as victorious warriors adorned their homes and galleries with the skulls of the defeated. The decapitated bodies of the fallen were often left behind to rot.

Eventually, it would be these reports that would spur Dutch authorities into action, though rumors have persisted of them doing so only to protect the oil-rich island of Tarakan. New expeditions were sent up the northeastern rivers to pacify the forests, though the relative remoteness of Pensiangan stunted many peacemaking attempts, as were the local accusations of broken trust. In most cases, arbitration became the end goal as tribal chieftains harangued each other over local hunting, farming, and fishing rights, while a sizable minority moved downstream to better be protected by their new colonial overseers. It wouldn’t be until 1908 that Dutch control was confirmed to north-central Borneo, and even longer for general peace to take hold.

However, the expeditions did result in one major (albeit off-shoot) incident: the highland adventure of Long Bawan. In 1907, the new Rajah of Sarawak, Clayton Brooke, organized an expedition deep into the kingdom’s mountains to halt the Ancur from spilling into his corner of Borneo. But in doing so, the Rajah and his men became the first lowlanders to walk the highland valleys of Borneo’s interior, which created a sensation across a war-weary Southeast Asia, searching for escapism [6]. Upon the expedition’s return, the subsequent coordinates of these valleys were noted with the largest of them, Long Bawan, being actually located inside the Dutch border.

Instantly, explorers and naturalists scrambled to witness the storied vales where, “golden fields rustled amidst cloud-topped peaks”, as Rajah Clayton described it. Local missionaries were just as absorbed; the Ethical Policy saw an upswing in Christianizing activities across the Dutch Indies with Calvinist and Evangelical societies pouncing on the discovery to save native souls. The first missionaries arrived in Long Bawan in 1909, altering the religious makeup of the interior forever…

Photograph of the local Dutch Reformed Evangelical Church of Long Bawan, circa 1931.

1. See post #945 on the Dutch East Indies.

2. IOTL, Dutch Borneo was divided into the Residency of West Borneo (capital: Pontianak) and the Residency of South and East Borneo (capital: Balikpapan). In the 1930’s, plans were made to centralize the above systems under a ‘Government of Borneo’, based in the south, that would have jurisdiction over the entirely of Dutch areas. However, the arrival of WWII dropped those plans flat.

3. Aristocrats from princely states really did became part of the Dutch civil service in the East Indies IOTL. Taking a leaf from the British, the measure was done to save the cost of administration and to disrupt as little of the elites as possible. This however meant a sizable number of sultanate families and aristocrats were seen as Dutch collaborators, which led to some massacres among their number during the independence period of Indonesia.

4. See Post #1,004 on how Britain and Austria-Hungary (well, Franz Ferdinand in particular) stumbled into perhaps the most unexpected event in Sarawakian economic history: the discovery of viable petroleum seeps.

5. All this, despite a few ITTL changes here and there, is an abridged and oversimplified version of the real-life Penghulu Bantin and his move from Sarawak to Dutch Borneo. The Iban chief was known to create trouble by waging his own wars and raids which incensed Kuching, whom Bantin saw as an illegitimate force upon the Dayaks. During the late 19th century, he was part of an alliance of chieftains that resisted Brooke rule, with his own son Inggol being killed by a punitive expedition of Rajah-allied Dayaks in 1898. His carefulness to avoid antagonizing the Dutch was also true, as he didn’t want another great enemy nipping at his heels; he eventually moved into Dutch Borneo in 1909. ITTL, the greater growth of Sarawak sped-up events early. A more complete telling of his war years can be read here, though you need to understand the Iban language first.

6. See Post #1,641 for Clayton Brooke’s expedition into north-central Borneo.

2. IOTL, Dutch Borneo was divided into the Residency of West Borneo (capital: Pontianak) and the Residency of South and East Borneo (capital: Balikpapan). In the 1930’s, plans were made to centralize the above systems under a ‘Government of Borneo’, based in the south, that would have jurisdiction over the entirely of Dutch areas. However, the arrival of WWII dropped those plans flat.

3. Aristocrats from princely states really did became part of the Dutch civil service in the East Indies IOTL. Taking a leaf from the British, the measure was done to save the cost of administration and to disrupt as little of the elites as possible. This however meant a sizable number of sultanate families and aristocrats were seen as Dutch collaborators, which led to some massacres among their number during the independence period of Indonesia.

4. See Post #1,004 on how Britain and Austria-Hungary (well, Franz Ferdinand in particular) stumbled into perhaps the most unexpected event in Sarawakian economic history: the discovery of viable petroleum seeps.

5. All this, despite a few ITTL changes here and there, is an abridged and oversimplified version of the real-life Penghulu Bantin and his move from Sarawak to Dutch Borneo. The Iban chief was known to create trouble by waging his own wars and raids which incensed Kuching, whom Bantin saw as an illegitimate force upon the Dayaks. During the late 19th century, he was part of an alliance of chieftains that resisted Brooke rule, with his own son Inggol being killed by a punitive expedition of Rajah-allied Dayaks in 1898. His carefulness to avoid antagonizing the Dutch was also true, as he didn’t want another great enemy nipping at his heels; he eventually moved into Dutch Borneo in 1909. ITTL, the greater growth of Sarawak sped-up events early. A more complete telling of his war years can be read here, though you need to understand the Iban language first.

6. See Post #1,641 for Clayton Brooke’s expedition into north-central Borneo.

Last edited:

Heh. Ijau Lelayang settled in Sentarum? Less problem for the Brookes, then.

Well, he did eventually move there. Now, he does it earlier! Too bad it's still unknown exactly where he was buried, though that may be what Penghulu Bantin wanted.

EDIT: He actually settled at the Ulu Leboyan IOTL. My bad.

Last edited:

Well, he did eventually move there. Now, he does it earlier! Too bad it's still unknown exactly where he was buried, though that may be what Penghulu Bantin wanted.

EDIT: He actually settled at the Ulu Leboyan IOTL. My bad.

I remembered there's an expedition by Sarawak National Dayak Association to his grave. It was in a slope of a hill just over the border.

I remembered there's an expedition by Sarawak National Dayak Association to his grave. It was in a slope of a hill just over the border.

You made me go down an internet rabbit hole searching up Bantin's grave for the entire day. There have been a few articles written about locating his final resting place, which seems to be on the top of Bukit Keruin in West Kalimantan, somewhere between the Ulu Leboyan river and the town of Putussibau.

However, for the life of me I could not find any Bukit Keruin in Google Maps or in any Indonesian maps of Kalimantan either

However, the gravestone also contains a few inaccuracies. For one, the Rajah that pushed against Penghulu Bantin during his warring times was Charles Brooke, and not James Brooke as mentioned. For another, the image they used is totally false, as Bantin was never photographed throughout his lifetime. The picture that the locals (and I) used is, in fact, a Dutch photograph of two Batang Lupar Iban Dayaks from the early 20th century. But with all that said, I can't really fault anyone for wanting their leaders remembered.

Also, along the way, I managed to stumble on news that the James Brooke film is already into post-production and will be shown later this year (if the current pandemic doesn't screw up things). Please, let it be uncontroversial... 😬

Last edited:

I still can't see how the chaos is bad enough that Sarawak ends up in control of all Borneo a century later. Which is surely where this timeline must go, yes?

In this day and age? Unless it flies under the radar of what passes for mainstream media and the 'internet consensus' these days, everything is either controversial due to hamfistedly pushing a narrative or not pushing a narrative enough.

Please, let it be uncontroversial...

In this day and age? Unless it flies under the radar of what passes for mainstream media and the 'internet consensus' these days, everything is either controversial due to hamfistedly pushing a narrative or not pushing a narrative enough.

I still can't see how the chaos is bad enough that Sarawak ends up in control of all Borneo a century later. Which is surely where this timeline must go, yes?

There's no doubt that Sarawak will be the most powerful country in Borneo when this timeline reaches the modern day, and hints have been dropped here and there that the kingdom may undergo yet another expansion phase or two - especially if local events go south in the future.

But for Sarawak to control of all Borneo... that, we shall see...

In this day and age? Unless it flies under the radar of what passes for mainstream media and the 'internet consensus' these days, everything is either controversial due to hamfistedly pushing a narrative or not pushing a narrative enough.

Well, a person can dream. 😬

Last edited:

But then it wouldn't really be Sarawak anymore....There's no doubt that Sarawak will be the most powerful country in Borneo when this timeline reaches the modern day, and hints have been dropped here and there that the kingdom may undergo yet another expansion phase or two - especially if local events go south in the future.

But for Sarawak to control of all Borneo... that, we shall see...

Another round of predictions :

France somehow gains Alsace-Lorraine. This seems implausible, but it is always called Alsace-Lorraine, not Elsass-Lotharingen, which implies it is French in the present. It may be during the Great War, but it is almost certainly later, most likely during the collapse of the German Empire.

Austria-Hungary will collapse. It is always referred to in past tense, and, although it is doing better than IOTL, it is still a Frankensteinian abomination of a country.

The Spanish Empire will collapse, most likely in a 3 way civil war. I predict that Cuba becomes an "independent" puppet state of America, Puerto Rico and Guinea Eccuatorial become part of one exile government ; the Philippines become another exile government along with the Congo, but is forced into whatever GEACPS is called ITTL, so we end up with JAPANESE-FILIPINO CONGO (preferably with at least one Zoroastrian Ainu, since, as @Al-numbers presented TTL as the spiritual successor to Male Rising, he/she should pick up the challenge that @Jonathan Edelstein accepted but then dropped).

Sarawak takes Kalimantan north of the Kayan river during decolonisation. Indonesia breaks up during decolonisation, probably with all 3 Dutch governates becoming independent.

Why do I have an idea of a German civil war or revolution happening in the future?

India decolonises approximately peacefully (i.e. without a big war of independence). In With the Crescent Above Us and Male Rising, there were independence wars against fascistic Britains, but it seems as if Britain ITTL will be more restrained.

There are probably going to be 5 uncolonised countries in Africa ITTL (Morocco, Liberia, Sokoto, Ethiopia, Ankole) as opposed to 1.5 (Liberia and sort of Ethiopia).

China will rise fast. If my predictions are correct, it gains stability and a sphere of influence of Siberia from the Great War (sure, it loses Shandong, but Britain and Germany will have to decolonise eventually).

European Russia will be under a revolutionary government, but what will it look like? I have no clue. Probably not recognisably communist.

France somehow gains Alsace-Lorraine. This seems implausible, but it is always called Alsace-Lorraine, not Elsass-Lotharingen, which implies it is French in the present. It may be during the Great War, but it is almost certainly later, most likely during the collapse of the German Empire.

Austria-Hungary will collapse. It is always referred to in past tense, and, although it is doing better than IOTL, it is still a Frankensteinian abomination of a country.

The Spanish Empire will collapse, most likely in a 3 way civil war. I predict that Cuba becomes an "independent" puppet state of America, Puerto Rico and Guinea Eccuatorial become part of one exile government ; the Philippines become another exile government along with the Congo, but is forced into whatever GEACPS is called ITTL, so we end up with JAPANESE-FILIPINO CONGO (preferably with at least one Zoroastrian Ainu, since, as @Al-numbers presented TTL as the spiritual successor to Male Rising, he/she should pick up the challenge that @Jonathan Edelstein accepted but then dropped).

Sarawak takes Kalimantan north of the Kayan river during decolonisation. Indonesia breaks up during decolonisation, probably with all 3 Dutch governates becoming independent.

Why do I have an idea of a German civil war or revolution happening in the future?

India decolonises approximately peacefully (i.e. without a big war of independence). In With the Crescent Above Us and Male Rising, there were independence wars against fascistic Britains, but it seems as if Britain ITTL will be more restrained.

There are probably going to be 5 uncolonised countries in Africa ITTL (Morocco, Liberia, Sokoto, Ethiopia, Ankole) as opposed to 1.5 (Liberia and sort of Ethiopia).

China will rise fast. If my predictions are correct, it gains stability and a sphere of influence of Siberia from the Great War (sure, it loses Shandong, but Britain and Germany will have to decolonise eventually).

European Russia will be under a revolutionary government, but what will it look like? I have no clue. Probably not recognisably communist.

But then it wouldn't really be Sarawak anymore....

Which does beg a few questions: would a nation that controls an entire island be called by the island’s name, or the nation’s? And what sort of future will befall the Kingdom of Sarawak and the island of Borneo?

Another round of predictions :

Ooh boy, some of what’s up there are closer to the mark than others. And I am very flattered that this TL is a spiritual successor of Malê Rising!

European Russia will be under a revolutionary government, but what will it look like? I have no clue. Probably not recognisably communist.

I really do need to make an update on political leftism soon. The Franco-Prussian War went mostly the same as OTL, so the Paris Commune and the collapse of the First International still happened, with all the infighting and acrimony that transpires.

And speaking of leftism, here’s something I also found out while searching for the location of Bantin’s grave; In 1893, the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) was founded in the Netherlands which espoused for workers’ rights and political leftism. One of the founding members of the Party was Henri Hubertus van Kol, an engineer and an early member of the First International. He arrived to the Dutch Indies in 1876 and would marry and have children there, and he would later espouse for reforms and sympathy for the colonized inhabitants.

However, there was another side to him. After becoming rich from his engineering work, Van Kol bought a plantation near the modern-day city of Bayumas in Java. Over there, he would employ poor Javanese peasants and their children to harvest coffee. He was positive about forced labour, believing it would induce locals to behave better, be proper, and eventually pay their own taxes. The most prominent early socialist in the Netherlands, Domela Nieuwenhuis, himself invested tens of thousands of Dutch guldens into the plantation and would later squabble with Van Kol over the dividends.

Along with this, Van Kol carried a disgusting amount of racism. The nicest things he could say were for the Malays whom, "come to work only when they need money for their daughter's marriage." From there, it all goes downhill; he described Chinese immigrants as "prone to illness...some of whom had to be deported because of 'bestial situations'". For the Javanese, he saw them as "indolent" and that, "many of them suffer from venereal diseases on arrival... and the many ronggengs [concubines] they present as their wives are sufficient to show their low level of civilization". He was charitable enough to provide the children of his plantation with school, Sunday's off, and have a Christian family oversee the workings, but he was far from being an anti-colonial champion.

In fact, a portion of his Bayumas plantation's profits were actually diverted to fund the Dutch labor movement and the SDAP! In parliament, Van Kol spoke for social reforms generally aligned with the Ethical Policy and even advocated for indigenous education, but he never espoused for self-determination of the Indies. He wanted the locals to improve, but also for them to be enveloped and absorbed into the greater colonial administration, with the Netherlands at the top. The correspondence between Van Kol and Domela Nieuwenhuis never spoke of the sheer ethical dilemmas of having colonial profits funding Dutch socialism (let alone the racism and hypocrisy), and Van Kol kept his plantation business out of public view.

He died in 1925, 20 years before the proclamation of Indonesian independence. As a spokesperson for the East Indies, Van Kol always espoused for more reforms and improvements for local life, but he never thought his political leftism could (or should) be applied wholeheartedly to the colonized.

EDIT: I may have overdone it all on Van Kol. My bad. 😬

Last edited:

Which does beg a few questions: would a nation that controls an entire island be called by the island’s name, or the nation’s? And what sort of future will befall the Kingdom of Sarawak and the island of Borneo?

Because there's the rump of a state called Brunei that stuck up like a sore thumb that's guaranteed not to be absorbed by Sarawak? Sarawak may conquered the whole island, but Brunei still controlled that corner. So Kingdom of Sarawak in the Island of Borneo is still valid.

It literally depends. Historiclly different dynasties in Asia would often have their Kingdoms known by the dynasties name. Joseon (Korea) Yuan/Ming (China). In south east Asia Thai or Myanmar dynasties often were named after the principalities they started from. Borneo/Sarawak could be seen as interchangeable, but to seem more inclusive, Sarawak may just rebrand as the "Kingdom of Borneo."Which does beg a few questions: would a nation that controls an entire island be called by the island’s name, or the nation’s? And what sort of future will befall the Kingdom of Sarawak and the island of Borneo?

Vietnam's dynasties literally named their country variations of "Great Viet", though Hồ Quý Lý called the country "Great Peace" during his dynasty's short-lived tenure.It literally depends. Historiclly different dynasties in Asia would often have their Kingdoms known by the dynasties name. Joseon (Korea) Yuan/Ming (China). In south east Asia Thai or Myanmar dynasties often were named after the principalities they started from. Borneo/Sarawak could be seen as interchangeable, but to seem more inclusive, Sarawak may just rebrand as the "Kingdom of Borneo."

Whatever, Sarawak will not rule over all of Borneo anyway, and it probably will not even rule over Borneo-minus-rump-Brunei.

[HUGE MAP]

I wonder if Sarawak may just expand enough to also include Western Kalimantan and "Great Dayak", they seem to be the most obvious bits of Dutch Borneo they might pick up eventually based on both geographic and cultural proximity.

I can't say for expansion, but I will say that parts of West Kalimantan share the same ethnic groups as those living in Sarawak proper - In fact, many of Sarawak's Iban ethnic group consider the Sentarum plains of West Kalimantan as their original birthplace. The Murut tribes of northern Sarawak and Sabah also have a lot of co-ethnics across the national border, and the central highland valleys share more in common with each other than their lowland counterparts.

Also, that map is both blessed and cursed, especially given the future of this timeline.

Strange and dangerous times ahead for the Dutch.

One possibility for Borneo is that Sarawak will help establish one or more other independent Bornean states on the island. Not wanting to share a border with a large possibly hostile AltIndonesia. And perhaps as part of the support see some border adjustments in Sarawak's favor.

Rather than ruling all of Borneo Sarawak could be secured as the leading state of the island.

One possibility for Borneo is that Sarawak will help establish one or more other independent Bornean states on the island. Not wanting to share a border with a large possibly hostile AltIndonesia. And perhaps as part of the support see some border adjustments in Sarawak's favor.

Rather than ruling all of Borneo Sarawak could be secured as the leading state of the island.

I have actually been wondering about that. Should a Republic of Indonesia form earlier in this TL, of approximately the same territorial makeup as OTL. Would they be hostile to Sarawak, even willing to go to war over it? Perhaps it would depend on how such a state forms.Strange and dangerous times ahead for the Dutch.

One possibility for Borneo is that Sarawak will help establish one or more other independent Bornean states on the island. Not wanting to share a border with a large possibly hostile AltIndonesia. And perhaps as part of the support see some border adjustments in Sarawak's favor.

Rather than ruling all of Borneo Sarawak could be secured as the leading state of the island.

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Share: