Mid-Great War: 1906-1907 Johor & Aceh (5/6)

...In a sense, the rebuilding of Aceh did not go as the Acehnese originally planned.

Despite all their efforts, it was incontrovertible that the Aceh War wiped the land clean of many treasured craftsmen and spice planters, most of whom fled to British Malaya, Temenggong Johor, Brooke Sarawak, or the D.E.I to escape the carnage. Later on, this void would be filled by more than 60,000 Chinese immigrants and settlers, grasping the opportunities created by the postwar-Acehnese court’s copying of Johor and Sarawak’s Kangchu policies. [1] Despite this, the Aceh War had given her neighbours a golden opportunity to develop their production of pepper, gambier, cloves, and other cash crops, forcing the sultanate out from its corner of the global market; Aceh would never enjoy her former prosperity as a spice producer.

Nonetheless, the pace of the sultanate’s rebuilding was impressive. When the Dutch finally left the region in 1888, they left behind an Aceh of scorched earth. Burnt fields, massacred villages, and destroyed plantations blighted the land with the Acehnese court having to depend on international charity to feed her population for the first few years. But the nature of the war had also protected a surprising source of potential revenue from overexploitation by the Acehnese: gutta-percha. By the late 19th century, the world went wild for rubber and Southeast Asia formed one of the largest raw producers of malleable latex. However, regional overexploitation had left many of Aceh neighbours bare of gutta-percha, with populations of the latex-bearing palaquium gutta trees crashing across the archipelago by 1884. [2]

This drop in production, also known as the Gutta-Percha Crisis, was the opportunity that Aceh sought. With their Ottoman saviour in need of raw materials for industrialization, Aceh stepped in as a grateful benefactor by harvesting and exporting wild latex to the Sublime Porte, collecting enormous profits along the way. In fact, gutta-percha exports and taxation would be so lucrative, it would form 1/5th of all total government revenues In Aceh by 1910. With the birth of the Great War, Aceh’s customer base would even grow as British (and later German) governments signed emergency agreements to claim even more of local wild rubber. While this trade would later collapse by the end of the decade due to overharvesting, the sheer scale of the revenues produced would set the Acehnese with more than enough financial capital to rebuild.

And rebuild, they did. By 1898, the capital of Kutaraja had been completely rebuilt with many new buildings set in the neo-Mughal and neo-Ottoman style as a result of local infatuation with the Islamic West. Once-despoiled residential quarters were back to overflowing as new immigrants flooded in from the countryside and beyond, carving off their own neighbourhoods. The sultanate’s conflict with the Dutch had also brought it enormous clout within the Islamic world, leading to an immigrant Turco-Arab-Hadrami population of over 8000 by the Great War. These new peoples, most of whom were traders, entrepreneurs or prospectors, even began to pioneer Aceh’s mining industry as ore seams began to be investigated across the interior mountains.

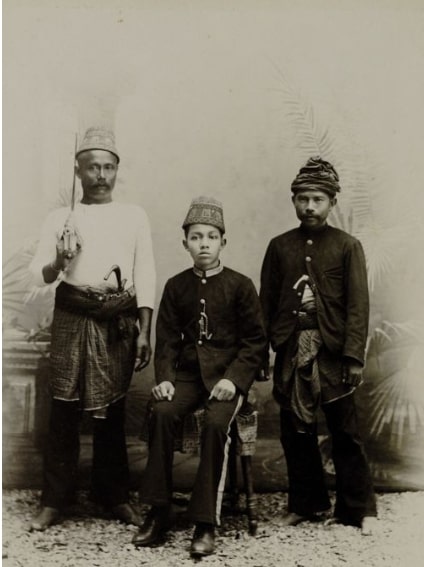

Aceh National Archives: ‘Locals at the market in Kutaraja’, circa 1905.

Despite all the progress, the sultanate government was still much too sceptical of Western nations to accept their promise of foreign investment. The fact that business dealings were also wrapped up in Acehnese customs – such as wearing traditional clothes provided by the palace court and high officials – further dissuaded many westerners (though not all) from dipping their toes locally. [A] There was also a tussle within the royal government to turn the clock back and relaunch Aceh as a spice producer with the associated agrarian-based economy to support it, as it was during the land’s heyday, which conflicted with more modernist voices who clamoured for greater exploitation of the region’s coal reserves.

Instead, the honour of industry went to Johor, which had carefully grown her spice economy to become not only the richest independent sultanate in the Malay Peninsula, but perhaps all of archipelagic Southeast Asia. After decades of careful investment – supplemented with the Kangchu system and the arrival of the Acehnese spice planters – the Johorean government had acquired enough capital to embark on projects that would make any subordinated sultanate cry; Johor Bahru was the first city after British Singapore to install electric lights and a sewage system, along with a myriad of semi-artisanal industries that blossomed as a result of royal patronage and international demand – a happy consequence of the state’s showing-off at the periodic World Fairs.

Another sign of forwardness came from one of Sultan Abu Bakar’s pet projects: a state railway. Taking a leaf from equally-rising Japan, foreign experts were hired to help the royal government in connecting the far-flung towns, villages, and plantations of the sultanate together, which had the added benefit of helping the tabulation of the state’s population, a process that has long thwarted government efforts. While such a project – which would entail cutting down virgin forests, blowing up hills and erecting new bridges – would have swallowed any local state with debt, Johor’s wealth enabled it to continuously fund the project [3] and even embark on some showpiece projects, such as the grandiose Johor Bahru railway station.

A cigarette card showing a locomotive of Johor’s state railway (above) and a photograph of the imposing Johor Bahru train station and hotel, completed in 1906.

The first assembly lines were built to churn out military kits that would supply British, Indian, and Ottoman forces across the Arabian, African, and Indochinese battlefronts. However, it wasn’t long before more commercial concerns mushroomed. The most famous of these were the canning wares of Jean Clouet, a Frenchman who emigrated to Singapore in the 1890’s to start a trade in selling perfumes and wines for the rich. However, his entrepreneurial spirt soon led him to import canned food to the Singaporean public, which led to both popularity from the locals and disgruntlement from the British, whom confiscated Jean’s business during the Great War. Fleeing to Johor, it wasn’t long before his idea for a canning factory found reception by the government and by 1907, the now-famous ‘Ayam Brand’ of tinned foods was officially launched. [4]

But for all this, Johor’s growth had one Achilles’ heel: the absence of coal and oil. Back then, the only nearby source of coal in Malaya was in Batu Arang, deep in Selangor. In an ironic twist, the sultanate that aimed to achieve industrial growth had to rely on oversea coal imports from Aceh, which saw the latter’s mining industry boom as a result…

********************

…Given Johor and especially Aceh’s connections to the Ottoman Empire, it was only a matter of time before Islamic reformism struck the two polities with full force.

For Aceh, their decades-long war with the Dutch had obliterated old styles of religious tradition and the royal government sought a fresh start by looking beyond their borders. Coming from the bottom, it was obvious to see why the Ottoman Empire was so enrapturing for many Acehnese; here was a beautiful, established, and powerful Islamic empire that fought against the Western Powers on several occasions, and sometimes won. The high culture of the Turks and Arabs – in all their arts, poetry, lifestyles, and philosophies – was worlds away to many Acehnese peasants and even nobles who had to content themselves with wooden homes and brick palaces. Students and travellers to Cairo, Alexandria, Edirne, and Kostantiniyye spoke of the cities festooned with enchanting mosques and bedecked in such wealth, people, and prosperity that made populated Kutaraja seem like nothing more than dust.

And of the Ottoman philosophies that Aceh beheld, two were held in the highest regard: Islamic Modernism and Pan-Islamism.

Given the battering it had against the Netherlands East Indies, a great many Acehnese students and courtiers saw Islamic Modernism as a way out for their homeland. Centred in the great halls of Cairo and Kostantiniyye and spearheaded by figures such as Sheikh Muhammad Abduh, the movement called for a rethinking of Islamic doctrine, the use of intelligence and reasoning, friendliness and cooperation between non-Muslims, and a reconciliation between science and spirituality. For the Acehnese whom listened, these were heady and incredible notions that went far beyond traditional homeland creeds. For those who subscribed to the philosophy, reinterpretations of sharia to reconcile scientific, technological, and social progress was seen as essential if Aceh were to rise again as a modern nation.

But equally as popular (and more forceful among the religiously inclined) was Pan-Islamism. This movement, partly borne by the rise of new creeds such as Deobandism and Wahhabism, calls for different paths: emphasizing Islamic unity over ethnic and national boundaries, religious revivalism, doctrinal purification from old practices, the upholding of traditional sharia (except in cases where it obstructs the Pan-Islamist ideal), and anti-imperialism. This ideology was especially attractive to religious students and pilgrims studying in Cairo, Makkah, and Madinah as they became aware of just how much western colonialism was so dominant worldwide. For them, Pan-Islamism became a clarion call for mass-resistance, organization, and international unity.

‘The Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo’, by Adrien Dauzats (circa: 1831)

By 1906, both these philosophies had taken root in mainland Aceh with the first political clubs coalescing around each ideal, formed mainly by returnees. However, many locals saw no wrong in subscribing to both movements in some shape or form; Acehnese society was still rural and thus heavily conservative, and religious orthodoxy in the form of Turco-Arab-centric practices was considered a respectable way of Ottoman emulation. However, there was an equal awareness that some modernization in the Japanese, Siamese, or Johorean style was important for Aceh to survive in a colonial-happy neighbourhood. In another vein, almost all Acehnese equated both Modernism and Islamism as supporting the Ottoman sultan as paramount caliph, a notion that was distasteful to several Arab and Turkish ideologues.

In Johor’s case, the ideologies of Islamic Modernism and Pan-Islamism took root in a different way. Similar to Aceh, the sultanate’s Malay youths and ulamas (clerical establishment) saw the Ottoman Empire as place of pilgrimage and education. However, the decades of partial cooperation with the British Empire saw a number of Malay notables seeing the British as a worthy emulator of progress, with the most notable effects being the persistent push for industrialization and the creation of western institutions such as a central bank. A number of Malay nobles also sent their children to be educated in Great Britain, though a majority still sent theirs to the universities of Cairo and Kostantiniyye.

As such, the currents of Islamic, Western, and Ottoman philosophies hybridized in a different way in mainland Johor, aided along by the sultanate’s equally mixed institutions of rule which stayed strong while Aceh’s was obliterated during their long war against the Dutch. This hybridity was soon given a name: Islah – ‘Reform’ in Arabic. For the newly-educated Malays, the Islah movement was more than just a philosophy, but a political and ideological creed to push Malay culture, scholarship, business, and thought away from the traditional creeds of the Malay ulamas - who saw religion in only spiritual terms and cared little for progress or British influence on everyday life.

One of the Islah movement’s early proponents, the Johorean Sheikh Faisal Tahir al-Jalaludin, summed up the movement’s goals in a 1906 pamphlet [5]:

- The reformation of Islam in Malaya and the disbandment of practices not of Islam;

- Practical considerations on workers welfare;

- Wealth pools for Malay businesses;

- Governmental support for Malay businesses;

- Emphasis on good education, attention and knowledge to the English language;

- Application of British progress to Malaya;

- The upholding of the Malay sultan;

- And the education, emancipation, and participation of women in Islamic, scientific, and political scholarship.

********************

Mazyar Ebrahimi & Jana Daghestani, Ottomanophilia: The Tale of Ottoman Influence in Southeast Asia (Journal of Southeast Asian Studies: 1979)

…To be fair, Aceh’s erring for the Islamic West wasn’t exactly a new thing. For centuries, the sultanate had looked towards the empires of India and Arabia as inspiration for local rule. In the 17th century, for instance, the Kutaraja court created the position of Shaykh ul-Islam as the supreme authority of religion throughout the land, in emulation of the Ottomans and their own ennoblement of senior jurists to dictate religious affairs.

But the Ottomanophilia of the re-emerging Aceh was much larger and deeper in scope, not simply confined to philosophy-waxing students and nobles. In northern Sumatra, the love for Turco-Arabian culture permeated through all fabric of life; Fezzes and robes became everyday wear for locals, while the homes of the wealthy became decked in Turkish carpets weaved as far away as Uşak or Bursa. Hookah and coffee culture rose to prominence in major towns – though this was partially aided by the growth of Chinese-run coffeehouses, which fiercely competed with their Arab and Turkish counterparts for new customers. Some Arab and Hadrami notables became employed as Aceh’s ambassadors to the wider world, such as the famed ambassador Habib Abd Rahman al-Zahir [6]. A number of Arabic and Turkish schools were even set up for young children and adults to master the languages, with exemplary students being offered a chance to study in the faraway Empire itself.

The most significant effect was in martial relations. Families with Ottoman links became highly sought after for Acehnese notables and even local townsfolk were impressed if a person managed to marry an Ottoman citizen. The influx of Turks, Arabs, and Hadramis moving in certainly kept the prospects afloat, lured in as they were by Aceh’s attempts to reopen and expand its economy from spice-farming. By the Great War, around 8000 Ottoman immigrants made Aceh their new home, with many intermarrying with local Acehnese for business or practical reasons.

But of all, the most prized match was to wed a fair Circassian. The sultanate had, along with the greater Muslim world, heard tales of the Russian annexation of the Caucasus Mountains and the expulsion of its Circassian inhabitants, and it too had been brought along into the romanticized portrayal of the ‘Circassian Beauties’, whom were seen as extremely beautiful and voluptuous. The Acehnese royal court became particularly enamoured, especially as princes and diplomats began to travel to Kostantiniyye for various affairs – such women were often presented as concubines by the court of Abdulhamid II as gestures of goodwill. As to whether these women consented to be married off and taken so far from home, their words are scant to be found; many Circassian-descended families are notoriously cagey of their histories and the Acehnese royal archives are just as secretive.

Personal photograph of Putri Ayshe Konca, a Circassian woman who was married to the crown prince of Aceh, circa 1907.

But most dark of all was the growing suspicion by some Acehnese of the land’s Chinese minority. Brought in by the Kangchu system to restart the spice economy, more than 60,000 Qing Chinese immigrants had settled in Aceh to plant pepper, gambier, and other spice crops. But the new arrivals quickly began to make themselves known in other ways by building their own villages, town quarters, and temples that honoured foreign gods. Some had even began to smuggle opium, which was still a legal good in British Malaya and the D.E.I. . Their foreign connections were also exploited in the form of new sundry stores and coffeehouses which began to grow faster than their local or Arab counterparts. Even the Acehnese court hired a Chinese Peranakan as their finance minister, further adding to the suspicion that, in one contemporary maxim, “We fought off one conqueror, only to be conquered by another”.

As a result, many locals began pushing for the institution of Ottoman-esque laws such as the Millet system, in effect to create a separate administration of law for the Chinese. But a few also began to push for the primacy of Islam and the Acehnese people vis-à-vis the increasingly large Chinese minority, calling for the restriction of several rights and freedoms in a manner reminiscent of Turco-Arabian dhmmitude – ironic given how such concepts were themselves being challenged back in the contemporary Ottoman Empire. As the Great War rolled on and the Balkan and Anatolian theatres were fought and slowly retaken, the calls for what to do with the local populace became mirrored in Aceh with what to do with the Chinese…

Photograph of a Chinese temple near the town of Meulaboh, circa 1910.

Such unions were uncommon but not unprecedented in Malayan history. As far back as the 15th century, there have been oral and written tales of Chinese women and men having Malay spouses. The growth of the mercantile Peranakan class was in itself a sign of how malleable locals were at the prospect. Given the dearth of Chinese women for many Kangchu settlers in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, it was inevitable for interracial marriage rates to start ticking upwards in the Johorean backwoods and market towns. While the most of these marriages involve Chinese men taking Malay women as concubines, a few did took the extra step of conversion to Islam or syncretise it with traditional beliefs of ancestor worship and native/foreign gods, giving rise to a new strain of a Malayan faith... [9]

But the biggest splash in this paradigm was taken up by none other than Sultan Abu Bakar himself. Over the decades, the man had become personable with a rich Cantonese entrepreneur called Wong Fook Kee, who helped invest in the modernization of Johor. Along the way, he began to ensconce himself into the sultan’s inner circle and decided to go further by presenting his own daughter Wong Siew Kuan as a prospective match. Abu Bakar was already married twice, but that did not stop the two from being wed in a public ceremony in 1886. Wong Siew Kuan subsequently converted and renamed herself as Sultanah Fatimah, and accounts report that she was surprisingly the most respected of all Abu Bakar’s wives, taking a keen interest in the development of Johor.

All this, despite Johor adopting a “Separate but Equal” policy for their Malay and Chinese residents, points to a clear shift in preference regarding spouses vis-à-vis Aceh. And with this, it is perhaps no wonder that as both sultanates began to influence their surrounding regions – Johor for Malaya and Aceh for Sumatra – both polities began to drift apart…

Wong Siew Kuan / Sultanah Fatimah (left) and her daughter Tunku Besar Fatihah (right)

Notes:

First off all, thanks to @frustrated progressive for helping me with proofreading!

Whew! This update was a mammoth of an undertaking. I have promised almost a year ago that we shall delve into how the Ottoman Empire impacted Aceh and Johor, and here it is. The previous interlude was meant to form an introduction to this piece, but the following paragraphs and passages became so long, I decided to post the interlude first instead of cutting it out for the sake of brevity and bloat-cutting.

Regarding the incidence of Malay-Chinese intermarriages, legends of such date back all the way to the Malacca Sultanate of the 1400’s in which a Ming princess named Hang Li Po was married to the Malaccan sultan Mansur Syah. However, Ming records show no such event taking place, although they do note the presence of Chinese communities, diplomats, and even graveyards around contemporary Malacca. More personally, the fact of such intermarriages are hard to ignore once you start looking up your family tree.

Also, the part where Abu Bakar married a Cantonese woman isn’t just a TTL event. The Johorean royal family really did marry non-Malays during the late 19th century with Chinese and Circassian brides becoming a part of several prominent families. To this day, a fair number of Malay-Muslim politicians claim some mixed Chinese or Eurasian ancestry, like Malaysia’s third Prime Minister who had partial Circassian ancestry. No less than the current Queen of Malaysia herself, Tunku Azizah Aminah, has openly stated of her Cantonese heritage (from her ancestor Abu Bakar’s marriage, no less!) and has said that, with some digging, she could retrace back her maternal lineage back to southern Guangdong.

[A] This practice of foreigners wearing traditional clothes before facing royalty and high officials was attested as far back as 1599! (page 60)

(B.) Opium sales and opium taxes made up a substantial portion of colonial revenues for the British and Dutch all the way to the mid-20th century IOTL.

1. See post #464 on the Kangchu system of Johor and Sarawak.

2. See post #896 on the growth and collapse of the Gutta-Percha trade in Southeast Asia.

3. The profitability of a spice-cargo rail line was seen even back then by the Muar State Railway, which was built between the towns of Bandar Maharani (present-day Muar) and Parit Pulai in 1890. Carrying spices and fruits from the two termini, the transport of goods and people was so profitable that there were proposals to extend the railway to further reaches of Johor. Sadly, they were never carried out and the line was eventually closed in 1929 due to soft ground and rising maintenance costs.

4. The Ayam Brand is a real brand of canned foods in Malaysia that was started by Alfred Clouet, a Frenchman who travelled to Singapore to sell luxury goods. ITTL, it was his TTL cousin who sailed to Southeast Asia and started the manufactory. When the Great War arrived, he moved the business (and factory) to Johor.

5. Every part of that list were the actual aims of the Islah movement in British Malaya, though it should be noted that the original espousers took some inspiration from both the Ottoman Empire and Kemalist Turkey, especially regarding women’s rights. ITTL, Johor’s long history with the British provided another point of hybridity into the reformist movement.

6. Habib Abd Rahman al-Zahir was an actual Hadrami wildcat of a person who led a colourful life serving in the royal governments of Hyderabad and Johor whilst also shuttling back-and-forth all over the Indian Ocean in trading various goods. But he was also inducted into the Acehnese court and became Aceh’s diplomat during the early years of the Aceh War, trying in vain to entice Ottoman intervention. ITTL, he was successful and continued to serve as an ambassador right up to his death in 1896.

7. Penang still has Armenian Street ITTL, and the continued influence of the Ottoman Empire in trade ITTL allowed some Armenians to still reside there during the Great War.

8. F o r e s h a d o w i n g . . .

9. M o r e f o r e s h a d o w i n g . . .

2. See post #896 on the growth and collapse of the Gutta-Percha trade in Southeast Asia.

3. The profitability of a spice-cargo rail line was seen even back then by the Muar State Railway, which was built between the towns of Bandar Maharani (present-day Muar) and Parit Pulai in 1890. Carrying spices and fruits from the two termini, the transport of goods and people was so profitable that there were proposals to extend the railway to further reaches of Johor. Sadly, they were never carried out and the line was eventually closed in 1929 due to soft ground and rising maintenance costs.

4. The Ayam Brand is a real brand of canned foods in Malaysia that was started by Alfred Clouet, a Frenchman who travelled to Singapore to sell luxury goods. ITTL, it was his TTL cousin who sailed to Southeast Asia and started the manufactory. When the Great War arrived, he moved the business (and factory) to Johor.

5. Every part of that list were the actual aims of the Islah movement in British Malaya, though it should be noted that the original espousers took some inspiration from both the Ottoman Empire and Kemalist Turkey, especially regarding women’s rights. ITTL, Johor’s long history with the British provided another point of hybridity into the reformist movement.

6. Habib Abd Rahman al-Zahir was an actual Hadrami wildcat of a person who led a colourful life serving in the royal governments of Hyderabad and Johor whilst also shuttling back-and-forth all over the Indian Ocean in trading various goods. But he was also inducted into the Acehnese court and became Aceh’s diplomat during the early years of the Aceh War, trying in vain to entice Ottoman intervention. ITTL, he was successful and continued to serve as an ambassador right up to his death in 1896.

7. Penang still has Armenian Street ITTL, and the continued influence of the Ottoman Empire in trade ITTL allowed some Armenians to still reside there during the Great War.

8. F o r e s h a d o w i n g . . .

9. M o r e f o r e s h a d o w i n g . . .

Last edited: