Perhaps. I shall think about itYes, but that's not to say that actually democratic countries can't use it. For instance, Bangladesh calls itself the "People's Republic of Bangladesh", but it's definitely not communist.

Something similar can be at play in TTL Cuba.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

New Deal Coalition Retained: A Sixth Party System Wikibox Timeline

Aye but there's a much more "special" circle farther down for Che GuevaraCastro is currently burning in hell.

The Poarter

Banned

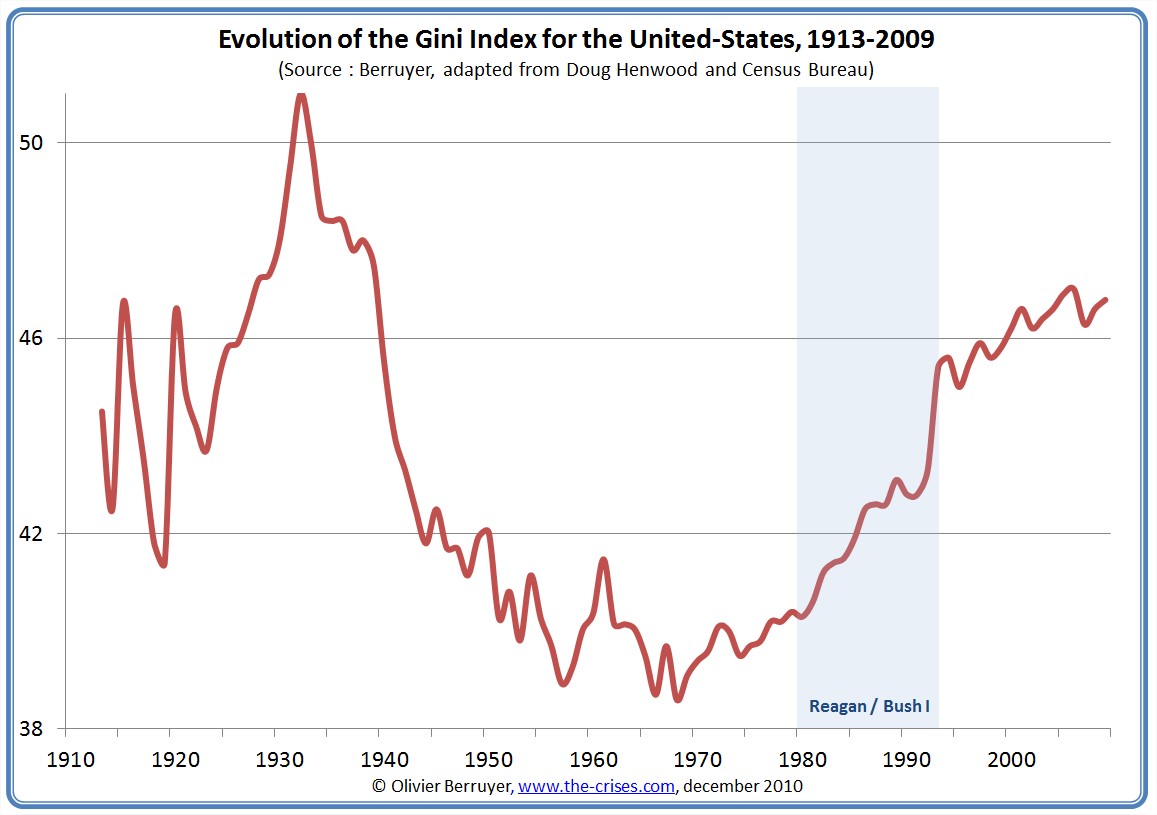

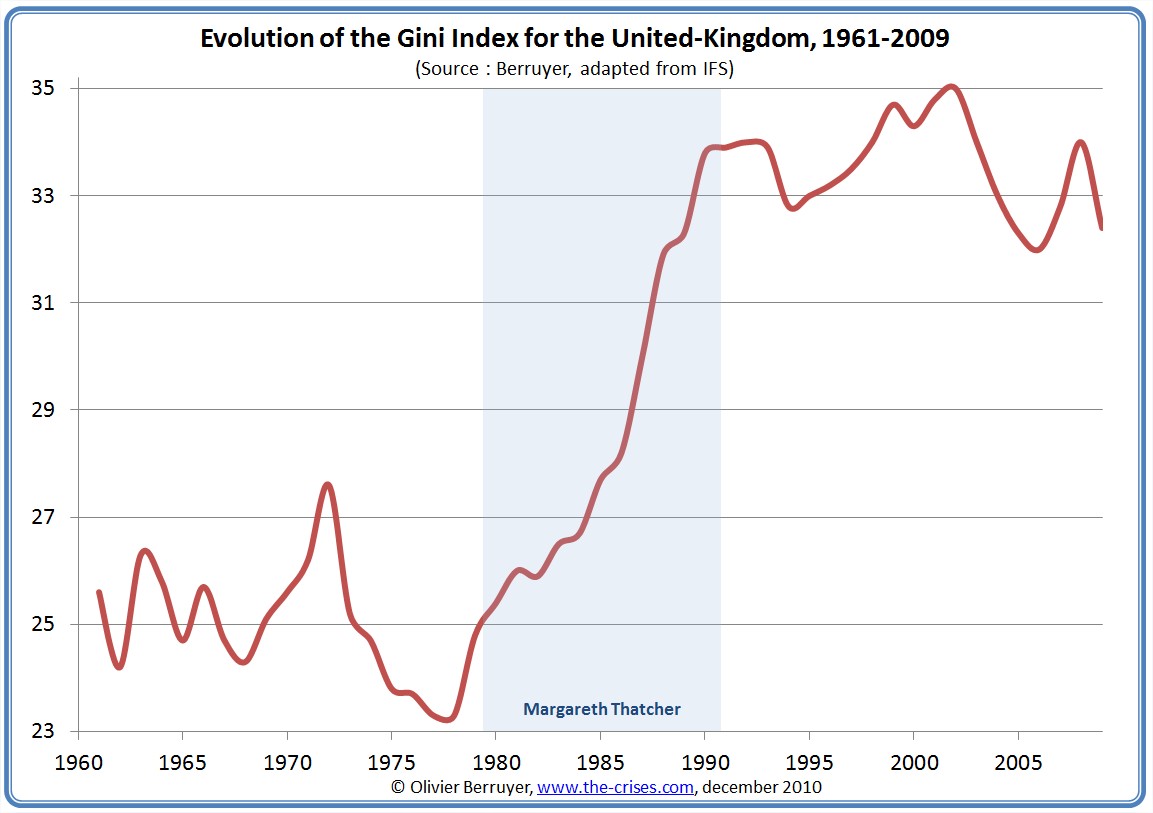

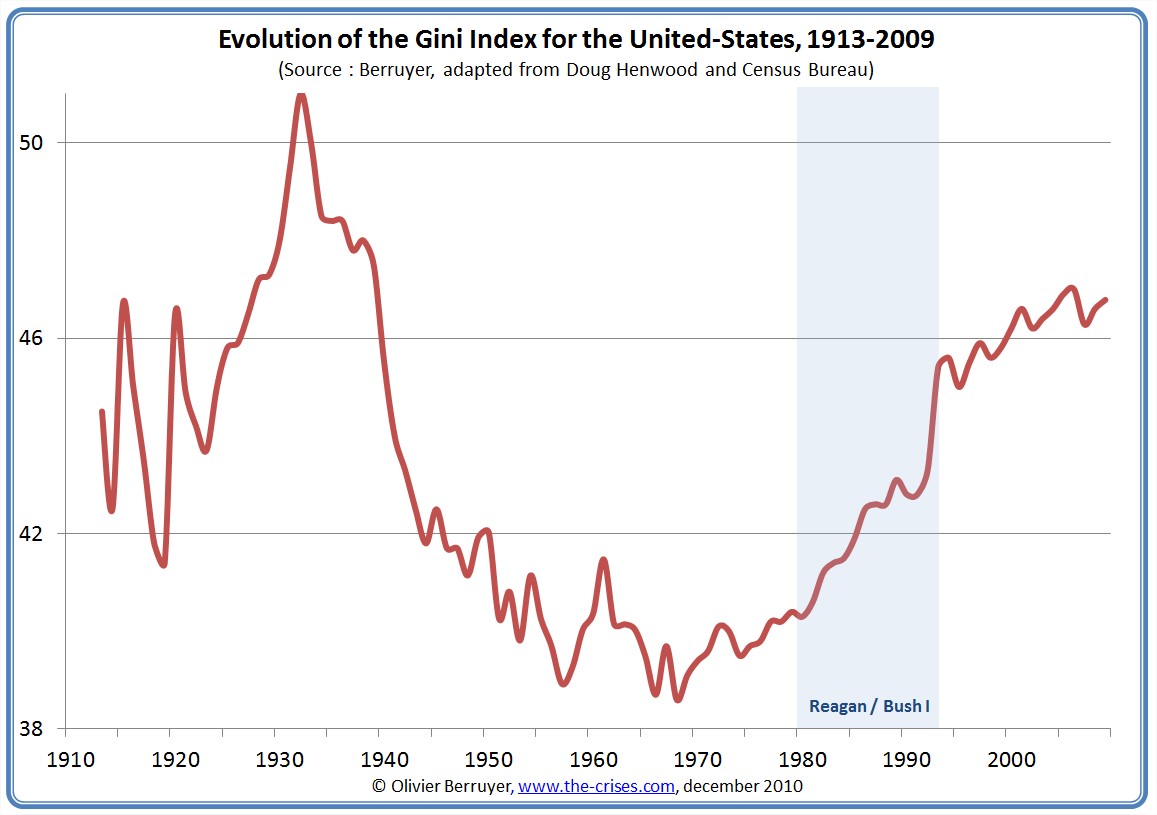

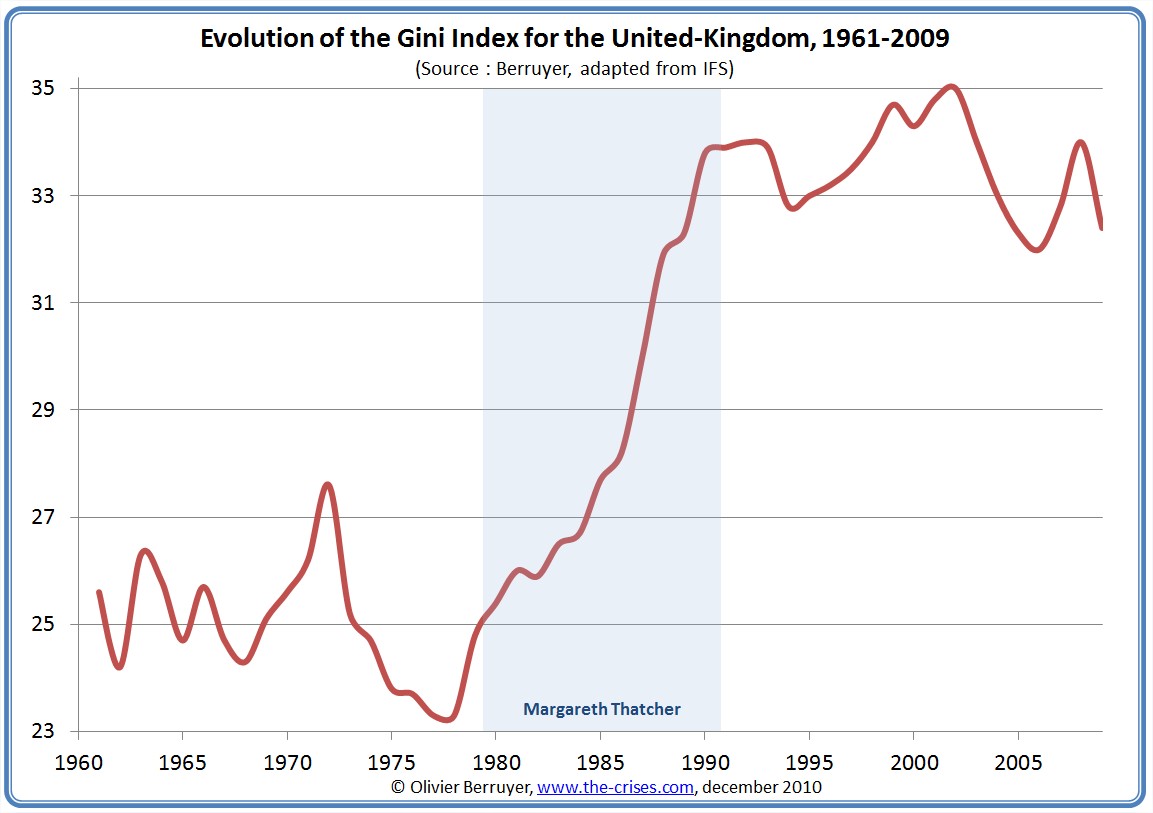

This article should give you some idea of the GINI index of the US and UK overtime. Also here are the images:

The Poarter

Banned

Bam! Here it is. Very little but it's a start. http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/AlternateHistory/NewDealCoalitionRetained

Tomorrow:

On the one hand I'm happy with an update on the way; on the other hand I dread what could happen.

Lost Freeway

Banned

What is the purpose of this?This article should give you some idea of the GINI index of the US and UK overtime. Also here are the images:

SCOTUS

“I made two mistakes, and they’re both on the Supreme Court. Glad Dick Nixon didn’t make the same mistake.”

-President Dwight Eisenhower, March 2nd, 1963-

“I made two mistakes, and they’re both on the Supreme Court. Glad Dick Nixon didn’t make the same mistake.”

-President Dwight Eisenhower, March 2nd, 1963-

As the fifties gave way to the sixties, what had to have been the most intriguing years in legal history had been entered into the nation’s case law. When Dwight Eisenhower appointed former Governor of California Earl Warren to the Supreme Court for political reasons, he never in his wildest imaginations figured the ramifications. On issues from Civil Rights (mostly beloved by Republicans), to law enforcement and civil liberties (not so loved by the same), the fundamental nature of the Warren Court sought to expand the scope of personal liberty farther than even the liberal New Deal Court was willing to acknowledge.

Such sweeping actions were tampered slightly with President Richard Nixon’s appointments of Thomas Dewey and Warren Burger to the court (both considered largely conservative in their outlook, though Dewey held a slight social libertarian streak). They joined with Eisenhower-appointed Justices Potter Stewart and John Marshall Harlan to form a decidedly conservative block – acting as a major veto of highly liberal proposals in concert with the FDR-appointed Hugo Black.

These examples could be seen as to how the justices applied the key avenues of change that the early Warren Court had concerned itself over. With the major Civil Rights decisions having mostly been ruled on, concern was passed on to more civil liberties concerns. Mandatory Bible readings were declared unconstitutional (except if it could be proven to have a secular reason), while the court demurred in Schell v. Bensalem Township to prohibit school directed prayer as long as it was 1) completely voluntary, 2) did not pressure non-conforming students to convert, and 3) allowed students to substitute their own prayers or customs. Free speech was expanded with regards to libel laws, but the Court upheld anti-incitation statutes under Brandenburg v. Ohio. Redistricting shenanigans were kyboshed in Baker v. Carr.

Largely, the latter half of the Warren Court was busiest in the term of criminal justice, liberal organizations such as the ACLU seeing an opening to dramatically expand criminal rights after the landmark 1963 decision Gideon v. Wainwright. Teller v. Indiana established the exclusionary rule regarding the 4th Amendment, Benitez v. California struck down status crime statutes, Witt v. Chicago established disclosure rules, and Tomlin v. Utah created the “Tomlin Warning” standard about informing criminals of their rights to remain silent and have access to a lawyer under Gideon. However, Justice Warren Burger would draw the line in his two majority opinions (decided by the conservative block of him, Black, Harlan, Stewart, and Dewey) in Kim v. Arends, upholding the revocation of citizenship as a punishment, and Dogger v. United States, which strictly defined a person’s area of protection from unreasonable search and seizure to his “current residence or domicile.”

Still, many landmark cases were decided. Orange v. Florida Department of Education established the “Orange test” as to whether a law is constitutional under the Establishment Clause. Carson v. California established the test for obscenity in Potter Stewart’s majority opinion. One of the most infamous decisions was New York Times v. United States. Made an issue when the New York Times newspaper received a collection of documents known as the “Pentagon Papers,” the Wallace Administration sought to get an injunction to block it being published. First, on prior restraint (of classified documents) and second, on executive privilege (the documents containing several memos between President Wallace and SecDef LeMay).

In the 1972 opinion written by Chief Justice Katzenbach, the Court made history by acknowledging Executive Privilege as a governmental right – however, it denied that portion of the argument. As for prior restraint, the Court ruled 5-4 that the First Amendment did not allow for the publishing of classified documents, but that the government needed to prove in a court of law that if the materials published would cause a “Clear and present danger” to American military or intelligence interests. The Pentagon Papers would later be allowed to publish subsequent to the Wallace Administration’s indictment of Daniel Ellsberg (he would later be convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison for mishandling and disclosure of classified documents).

-------------------------

What had to be the most influential legal development in the early years of the Katzenbach Court concerned the right to privacy. Although it wasn’t enumerated as a right in the Constitution, the Warren Court had declared it a right in Griswold v. Connecticut, where they struck down a CT law prohibiting the sale of contraceptives. It was the first acknowledgement of the right legal scholars had been debating, but for the rest of the decade there wasn’t any further action on the subject, Warren and Katzenbach leading the other justices to deny acceptance of other privacy cases. That was until the end of the decade, and on a surprising cause.

In 1969, Elias Henry was arrested by police in St. Cloud, Minnesota under the state’s sodomy law for consensual, homosexual intercourse. His partner managed to get immunity for testifying against a local narcotics dealer, but Henry wasn’t so lucky. He appealed his conviction in the Federal System by claiming that the sodomy statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment and the right to privacy under Griswold. The District Court upheld his conviction, as did the three-justice panel of the Eight Circuit, but an en banc decision by the Eight Circuit written by Judge Harry Blackmun reversed the prior decisions and struck down the law. Minnesota appealed, and the Supreme Court decided to hear the case.

In what would be Byron White’s first case after his confirmation, the Supreme Court split. It would be Justice Thomas E. Dewey who wrote the majority opinion in Henry v. Minnesota, (considered to be one of the most famous actions of his entire career), joined by Katzenbach, Brennen, Marshall, and White – Harlan, Stewart, Burger, and Carswell dissenting. “The Defendant is entitled to, at the very least, privacy for his private life,” Dewey wrote. “The State cannot demean his existence or control their destiny by making his private sexual conduct a crime.” However, he hedged on the broader issue of privacy, stating that “This ruling is merely to conform to the narrow aspect of whether it is constitutional to regulate the sexual conduct of consenting adults. Absent vital state interests such as preventing prostitution (among others), there exists no greater reason to apply the right to privacy than to one of the most emotional and intimate acts in human existence.”

Public outcry was fierce, protests held across the nation against what John G. Schmitz called the “Agenda of Homosexual Perversion.” Riots would later break out between them and pro-Henry counter-protestors in San Francisco and New York, the Henry Riots largely credited with the birth of the gay-rights movement in the United States (Thomas Dewey would be considered a hero to LGB advocates the world over for his ruling, which even he considered “far ahead of his time”).

Still, the right to privacy was still very much in limbo. Griswold had entered it into the record, and Henry extended it to certain sexual matters that Harvard Professor Archibald Cox would famously write “Was so blurred that no one knew where arraignment court ended and privacy began.” No one could tell what the right to privacy entailed as a whole. That was until Jenna Hanson was denied an abortion in Bowling Green, Kentucky right after Bobby Kennedy was sworn onto the Court.

Arguing that the right to privacy applied in this case, Hanson’s ACLU lawyers appealed to SCOTUS after the District Court and 6th Circuit denied most of her arguments. In late 1973, willing to finally put the issue to bed after nearly a decade of judicial limbo, certiorari was granted and the case was heard in December of that year.

Justice Byron White, in which he was joined by Justice Burger, wrote a concurring opinion on the matter that illustrated that if the Court reversed the 6th Circuit, it would not be expanding privacy but be creating a whole new right. “I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the judgment of reversing the lower court’s decision. The Court would then simply fashion and announce a new constitutional right for pregnant women and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invest that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes.” He also inveighed on the problem of juggling the right of the fetus over that of the mother, writing "The plaintiff in her argument values the convenience of the pregnant mother more than the continued existence and development of the life or potential life that she carries."

Justice Robert F. Kennedy wrote a unilateral concurrence, beginning with the disclaimer that “I do believe that a woman should be able to have access to such a procedure denied her under the Kentucky statute.” He continued to state that he wouldn’t vote to overturn the law, writing that "Such a ruling would rob the people of Kentucky the very the freedom to govern themselves. Over an issue as divisive and problematic as I believe this would be, it best be decided not by judicial fiat and instead by the process of democratic government our country holds so near and dear."

Justice William Brennen, joined by Chief Justice Katzenbach and Justice Marshall, wrote a scathing dissent. “In a line of decisions …. the Court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy, does exist under the Constitution,” Brennen wrote, continuing to say “This right of privacy …. is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy. The detriment that the State would impose upon the pregnant woman by denying this choice altogether is apparent.”

Social conservatives across the nation hailed the ruling. Liberals denounced it, but were heartened by the fact that the right to privacy had basically unanimous support from the Justices. What was called the “Carswell Test” was instituted to decide right to privacy cases regarding the state’s authority under the 10th Amendment: “benign effect” = unconstitutional while “life and limb regulation” = constitutional. Many observers felt that the broad-ranging decisions of the Warren and Katzenbach courts to expand the breadth of personal rights and liberties beyond where many considered proper was beginning to come to a halt. A welcome development from the countless decisions of the Warren Court and Dewey’s opinion in Henry.

However, President Wallace knew that Hanson could have easily gone the other way. Worried about his legacy, political expediency forcing the White and Kennedy nominations when in reality he wished for justices similar to Carswell, the President began to scheme of a way to secure a proper legacy to preserve the moral and traditional fabric of America.

Last edited:

However, President Wallace knew that Hanson could have easily gone the other way. Worried about his legacy, political expediency forcing the White and Kennedy nominations when in reality he wished for justices similar to Carswell, the President began to scheme of a way to secure a proper legacy to preserve the moral and traditional fabric of America.

In what way do you mean?Have you been reading my TL, Congressman?

Lost Freeway

Banned

Social conservatism seems to be on track to being more successful.In what way do you mean?

In some ways, yes. Sodomy Laws were overturned 30 years earlier on the other handSocial conservatism seems to be on track to being more successful.

Well shit. Perhaps same-sex marriage issues will get supporter far quicker than OTL?

Doubtful. The same shock to the establishment that happened in the 1970s that led to social liberalism blooming didn't happen ITTL.

Share: