I think I need to clarify that this TL’s focus is on visual and experiential aspect of the history.

Political and military events are only the background story. For instance, the Khitans did have a strong navy ITTL, but no mention is made on this because military history isn’t the focus.

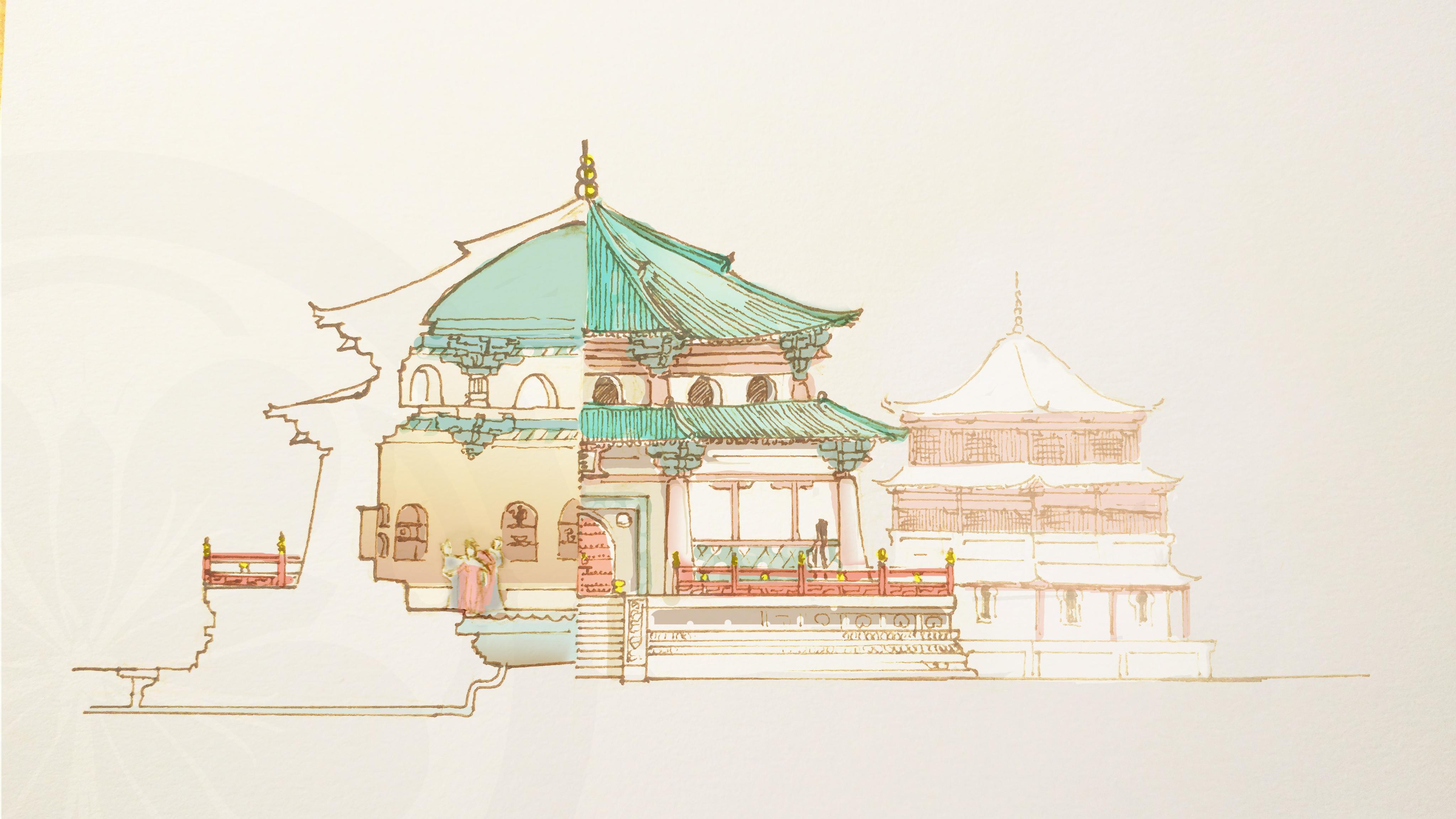

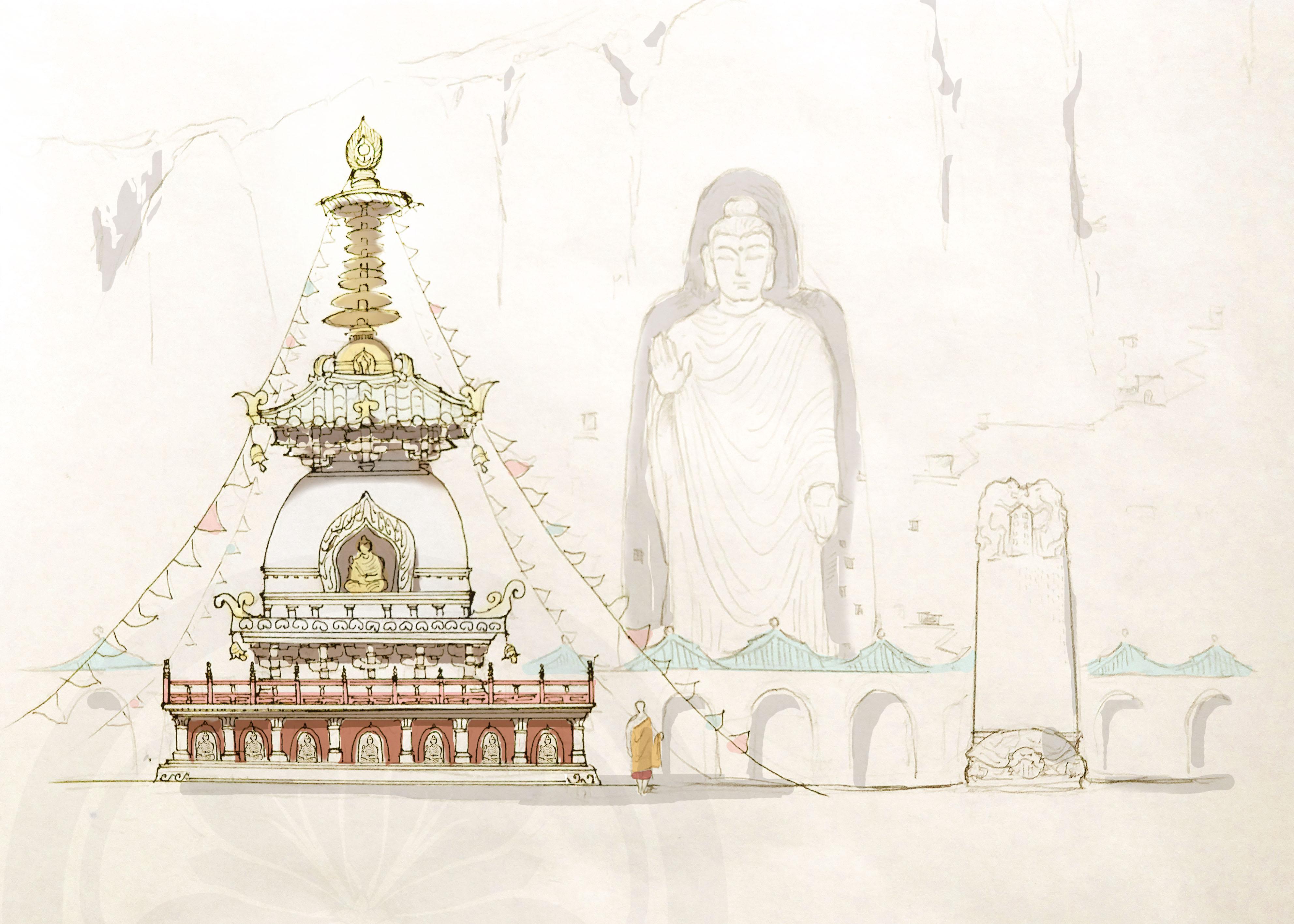

We need to know more about Indian Buddhism, Buddhist art and architecture around 1200, Indian lifestyle and customs in the middle ages, local produces and scenic spots, Indian folk literature and drama, etc.

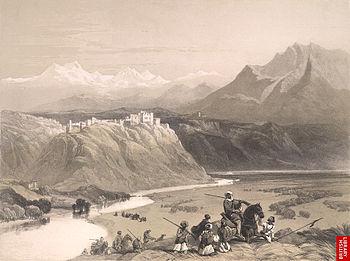

Basically, Indian living environment and visual art after the end of Gupta Dynasty and before the rise of the Delhi sultanate.

For these, what sources would you guys recommend? In forms of pdf and webpages.

Political and military events are only the background story. For instance, the Khitans did have a strong navy ITTL, but no mention is made on this because military history isn’t the focus.

We need to know more about Indian Buddhism, Buddhist art and architecture around 1200, Indian lifestyle and customs in the middle ages, local produces and scenic spots, Indian folk literature and drama, etc.

Basically, Indian living environment and visual art after the end of Gupta Dynasty and before the rise of the Delhi sultanate.

For these, what sources would you guys recommend? In forms of pdf and webpages.

Last edited: