Does His Majesty truely believe the House of Brandenburg can draw the winning ticket twice in the same lottery?

- Hermann von Moltke

Prussia in Paradox: Mobalization and Manuvers in Northern Europe

Another question that befuddled the Italians was also first on the minds of the forgien agents in Frankfurt and, once the news of Prussia's self-imposed exile from the Confederation became known, most of the political class of Europe. Why, with his armies already fully mobalized and clearly poised to threaten the minor German states, the Italians clearly poised to assist them, and Austria's aggrivation of the court in Keil and provocative, dubious move to integrate Venetia into the Confederation providing a suitable casus belli, was King Wilhelm holding back on issuing a formal declaration of war? Given the Confederate armies were still scattered and not yet at full strength, it would have been all the easier to take them out peicemeal with a quick move on either the Main or Northwestern Principalities. The answer to this question, if the Italians had been able to get the information that fast, could be found in events unfolding on the opposite end of the Germanies.

The borders of the Jutland Penninsula were rapidly developing into a mirror of their Italian counterpart, as the parties in and around Kolding were carefully trying to push their interests while preventing an outbreak of violence. As Ex-Major Ake's movement coalesced; absorbing virtually all the independent milita groups and attracting a steady stream of new volunteers, both the Danish government and the self-proclaimed "Slesvig Constiution Assembly" had begun to worry that what they'd previously considered a gathering of hotheads might actually attempt a filibuster. Such an invasion, even if they harshly denounced it, would no doubt be seized upon by the Augustenburgs and their patrons as the excuse they'd been looking for to declare the Estates to be in open revolt and dissolve their regional autonomy. Instead of being able to take their time to cultivate international support and convince the Duke that he could get better terms by conceding to a separate Constiution rather than throwing the question to Great Power mediation, where he faced the real possability of losing Slesvig entirely, the Assembly was coming under ever more instant requests from the Danish officals and represenatives of forgein courts to make a clear statement of intent before the Pan-Nationalists made that statement for them.

With these "requests" backed by over 10,000 guns: not only Ake's Frikorp but the Danish 7th and 8th Brigades which had been deployed under Col. Max Muller to insure there was a military presence between the potential expedition and the borders, the Slesviggers decided they could no longer afford the luxary of debating the finer points of their petion. On the afternoon of June 20th they presented, "On the request and for the approval of our sovergein Duke Frederick, this Constiution for the Duchy of Slesvig". To save time and present the weight of precident, the document borrowed a great deal of language from the Danish Constiution of 1863, pumiligating a position for Holstein over Slesvig virtually identical to that the Danes had proposed for themselves. In the spirit of the Treaty of Ribe, London Protocols, and unbroken traditions of the region the Duchies would be "Together and forever unseperated, the law of Succession being identical in Slesvig to that of Holstein under a single Constiutional Monarch", and would have a joint Parlament to cover the mutal affairs of forgein relations, a common army and Navy (The territorial Hjemmeværnet and Landwher alone being under local control), all matters relating to the Eidar and developments off it, management of a shared National Bank and Custom's Office (Implying a common currency, commercial treaties, and monetary policy), and administration of the capital and any other mutually held lands (For example, potential colonial territories). However, the document also guranteed the "Protection of Danish as the language of society, bussiness, and government" and "That the status of the Duchy as a distinct and independent entity shall remain forever unquestioned", while reserving for a popularly elected legislature (Rigsradet ) broad powers of domestic affairs. Most controversial, but vital to placating the Nationalists, the Constiution clarified that on matters of education, immigration/citizenship, and state employment requirements the Crown would only have a suspensionsry veto.

The document's conclusion, however, was an entirely original act of genius. For while submitting to all of Duke Fredrerick's explicent requirements: agreeing to petition on it's own behalf for membership into the German Confederation and

Zollverein , recognizing his sole right to the throne, and even formally waiving the obligation to hold the plebicite of 1864, the finishing petition to the Duke clarified that, if he had any disagreements with the terms, the Assembly would retroactively approve any changes agreed to by resolution of an international conference. While on the surface this appeared to be yet another concession: surrendering their absolute authority on the matter, in practice this could only play out to their advantage as Fredrick's annexationist stance was bound to be outvoted, with its only supporter being his Prussian allies. Backing up this stance was the fact that back on May 28th France, Great Britain, and Russia had already issued an invitation to the Central European powers for just such a conference for the settlement of the great regional questions: the status of Schleswig-Holstein, the conflicting claims of Vienna and Turin, and Prussian proposals for reforming the German Constitution to make the Federal Assembly a popularly-elected rather than court-appointed body (A move that would vastly boost her own influence at the expense of the minor state), which Prussia and Italy had already consented to. By placing the issues in a context where international arbitration would be favorable to Austrian interests (Prussia having surrendered any moral authority on Confederation reform by suspending her participation and supporting autocracy in the S-H matter, Venetia now being a member of the Confederation, ect.), the last hurdle to unanimous acceptable would easily be overcome and place the ultimate decision in the hands of Napoleon and Russel; men who were widely known to favor the return of Slesvig to Denmark. The Assembly in fact direct reference to the joint Conference proposal in their statements surronding the document; getting parallel supportive declarations from Copenhagen and Stockholm, the later sending an offical offer to Kiel, Paris, London, and St. Petersburg to host the meeting as a "neutral party" who, the Sublime Porte apart, alone had no stake in the questions on the table. Upon receiving the request, the Duke found himself hoisted by his own petard: his call for constitutional reform in Holstein and his Prussian patron's insistence on pushing through reform of the Confederation at risk of becoming laughing stock if they were forced to defend reasonable calls for representation in an open international forum.

Faced with this conundrum, the Holstein government waited to issue a reply to what was in effect an ultimatium, reaching out to Whilhelm's court for advice and gurantees of support if they should deny the Kolding Constitution and unilaterally declare the Convention being held in Kiel to be writing the governing document for both Duchies. Berlin, however, was facing its own political divide as the Crown Council split over which stance posed a greater risk to the maintenance ot the government. One faction, lead Von Roon, held that the

Landtag was already looking for any excuse to call for a new government due to the lack of a present Minister-President, held in check only by the mobalization and looming war threat that provided both the means and justification for declaring Martial Law. To submit to arbitration now; a move that would certainly requiring standing down the army as a show of good faith and further delay the Augustenburg Duke's arrival behyond the forseeable future, would no doubt trigger a demand for elections that could only prove disastrous for the crown-supporting Prussian Conservative Party. Further, were they to attend such a conferance and later deny its terms, the danger of other Great Powers throwing their weight behind Austria coulden't be dismissed and "Would produce a frightful scene, with us obliged to mobalize the forces yet again with Russia and France looking on greedily and Italian assistance in doubt". The expenses of such a remobalization, with the money from the previous year set to run out and the government lacking the support to obtain a new budget bill that didn't containing terms which placed explicent boundaries on royal power without the cloak of fighting an unavoidable war in the face of Austrian agression; an argument which would hardly hold water if they instigated the conflict in spite of a European concensus. The only way to avoid a "2nd Olmutz" then was to declare war now and pre-empt any peace iniative and lock in Italian commitment.

To the Crown Prince and his supporters, the real threat wasn't a 2nd act to the tragedy of 1849 but 1854, with Whilhelm playing the role of Czar Nicholas. "Anyone who believes the British and French will merely 'look on' as we make a naked grab for hegemony in the Germanies, to say nothing of setting up an internal situation bordering on civil war, is a fool" he would plainly argue in his report in the matter. With the need to cover so many fronts against the forces arrayed against them: the Rhineland, Silesia, the Main, the Hannoverian border, and secure Schleswig against the Scandinavianists and a Danish detachment who's intentions were still in question, could only end in the peacemeal destruction of the military and the prestige of the dynasty. Without these twin pillars of stability, he argued, the crown would be defenceless against not only calls for reform from within the government but ran the risk of something far worse: an uprising on the part of Republicans and Socialists. If they were going to declare war, than, it couldn't be for the sake of Holstein: they would need to find some casus belli that would both gain the sympathies of the

Landtag and create enough ambiguity on who was the offending power to keep Napoleon III honest with his promise of neutrality.

As the third member of the advisory triumvirate, Von Moltke would ultimately serve as the decisive weight in the matter. As much faith as he placed in the superiority of his reformed Prussian army in both tactical command and equipment; particularly in the question of small arms, his dedication to the dictates of Clausewitz were that much stronger. From that prespective, he had to concede that the uncertainty of war and the troublesome political and strategic situation made it unwise to "Wager the Crown on the prospects of drawing a hand better than three kings" (By which he meant a war against Austria, Britain, and France simutaniously). Framing the politics in military terms, he convinced Whilhelm that Austria could only be decisively defeated if isolated, as Denmark had been two years ago and Russia had been over the over the Turkish disputes, and "struck then in her exposed flank" by a "cohaliton of two or more powers". So long as the treaty with Italy stood, they could fufill the second requirement, but the first would require starting the war with an action that would play well diplomatically and, ideally, create a better initial strategic position so he could concentrate Prussia's numerically inferior armies at a decisive point in order to achieve a position of superiority. That way, Austria would only be able to seek peace terms from a position of weakness, limiting the ability of the Great Powers to oppose Prussian interests through mediation.

The tool to bring about those conditions could be found in the German National Union; the premier organization for liberal Pan-nationalists throughout the Germanies. With membership reaching into even the highest level politicans in many of northern states, they'd become vocal advocates of Whilhelm's calls for reforming what they perceived as the highly reactionary structure of the Federal Assembly, which they saw as a mere tool of the monarchies to maintain their power against the rising tide of liberal sentiment. If properly spun as a move by the Habsburgs to further stack the Assembly in favor of autocracy by adding a puppet representative from Venetia and denying the constiutionally minded Holstein their mandated vote, this could open the door for intrigue by casting the Prussian withdrawal and war as an opportunity to purge the rot from instiutions that had proven behyond saving in any other way. As it just so happened, Whilhelm had just such an opportunity in mind... it would just require some time to properly organize.

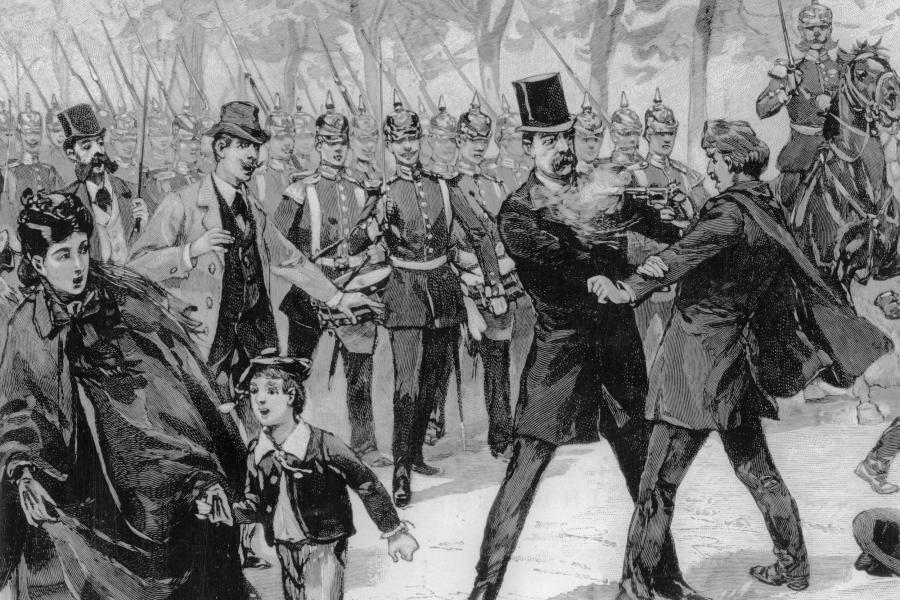

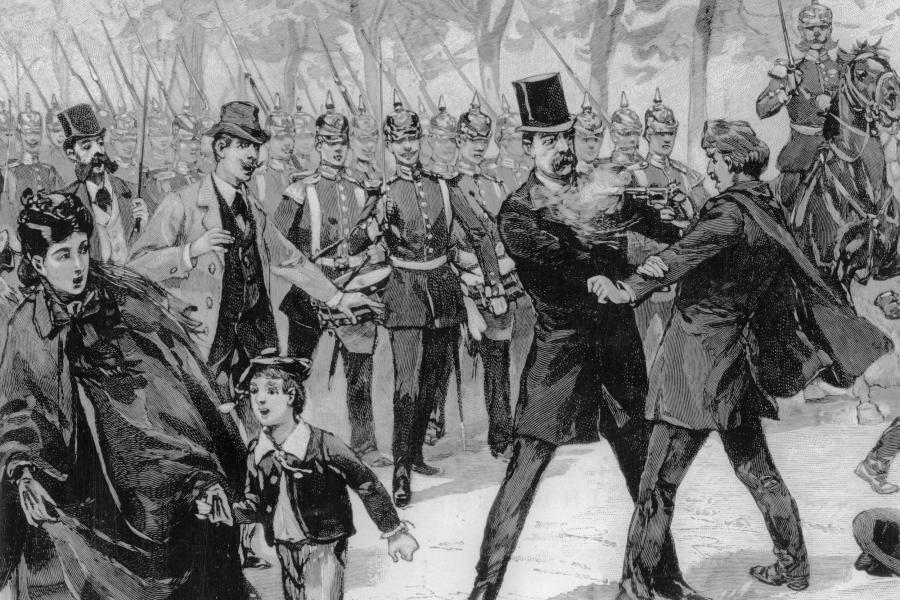

Immediately, discreet channels were opened up with the highest-officed member of the GNU; Rudolf von Bennigsen. As a former Minister-President and current head of the Estates Assembly of Hannover, his strong opposition to the despotic, obstructionist policies of his monarch George V was well known. With the King's absolute insistence on pursuing a war with Prussia whatever the risk, their relations had been streched to the breaking point as von Bennigsen was equally dedicated to avoid what he saw, given their isolation from any allies and the King's bone-headed defusion of the army, as an act of national suicide. Indeed, while reveiwing the previously private documents while emptying Bismark's office it was discovered the Minister had, just prior to his assassination, already set up talks with the Hannoverian to gather support for their jointly desired Confederation reforms. Acting as a figurehead for the Court, the Crown Prince; with a reputation for liberal sympathies, used the planned talks as a springboard to get the Minister's ear.

Prussia, he assured them, had no desire for war with Hannover; indeed, it was in hopes of preventing such a war that his father had suggested their army demobalize back on the 15th, in tandem with their withdrawal from the "irredeemable" Confederation (The coincidence of the dates a stroke of luck he tactfully exploited). The kings and dukes sadly, no doubt dancing to the tune of their Habsburg master, insisted on dragging out the crisis over the heads of their people, while Prussia and Holstein were taking a stand to open the way for a new Confederation built on popular, rather than princely, control alongside their ideologically impeccable Italian allies. Their target then wasn't Rudolf's country but rather its tyrannical crown, one that "if you have the courage to rise and take it for a more worthy head, you will find in my country as firm an ally as the Augustenburgs have".

This offer to back a legislative coup, packaged with a signed and sealed pledge from the Privy Council verifying their approval and a pledge to guranteed the independence and territorial integrity of the Kingdom "against any party, forgein or domestic" was sorely tempting to the former President, who saw his first duty as safeguarding the welfare of the state over that of it's King. The oppritunuty was tempting enough to raise the possability with known sympathizers in the General Staff who, keenly aware of the hopelessness of the military situation, were willing to take the gamble of the Prussians coming in as friends while they still had an intact army, at least compared to the guranteed lose of them marching in as conquering enemies. So it was that preparations began: the following days seeing a steady rescheduling of the men at the signal corps and telegraph stations, reliable officers being issued sealed orders, and units being moved around to position friendly forces closer to the interior and known Royalists closest to the Prussians until, on the 27th of July, the message went out.

"Impliment Operation Cambridge"