23. The Tet offensive

As the communist Vietnamese forces prepared to launch a major offensive against the Republic of Vietnam and its supporters, they wanted to give an knock-out blow to the enemy forces. Thus, the offensive was to coincide with the annual Lunar New Year (Tet) celebrations, which were traditionally a time of peace, and a cease fire had been negotiated for the holiday. However the offensive was designed to put an end to the resistance led by Saigon and supported by Washington, hoping to catch them with their guard down. Thus, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and the Viet Cong units launched attacks across southern Vietnam in the early hours of the of February 1.

Enemy forces attacked major population centers of the Spanish controlled Go Gong district. The district capital, My Tho, was a quiet town where the Spanish soldiers used to have their laundry done and to buy fresh food, souvenirs and ice, in spite of being a prime target for the Vietcong, that tried to promote a communist uprising among the local population.

First, at 5am two Vietcong companies attacked the Logistics area to the south-west of the town while other small forces attacked other important installations. A platoon assaulted the hospital, but the Spanish troops managed to defeat them. Supported by mortars and artillery, they were, first, keeping at bay the atackers and then defeated them, preventing the enemy for destroying several bridges in the area, even if the Logistic area suffered heavy damage.

As the enemy attack winded down, the Spanish Headquarters received a request for help from a senior US advisor who simply told them that two VC platoons were causing havoc in the area close to the road that linked My Tho with Saigon. With this limited information, they sent a small Ready Reaction Force (RRF) consisting of two platoons from the “A” Company of the 3rd Batallion, commanded by Major Bartolomé Henriquez, who was briefly reported before going into action. Major Henriquez had only been in Vietnam for around a month.

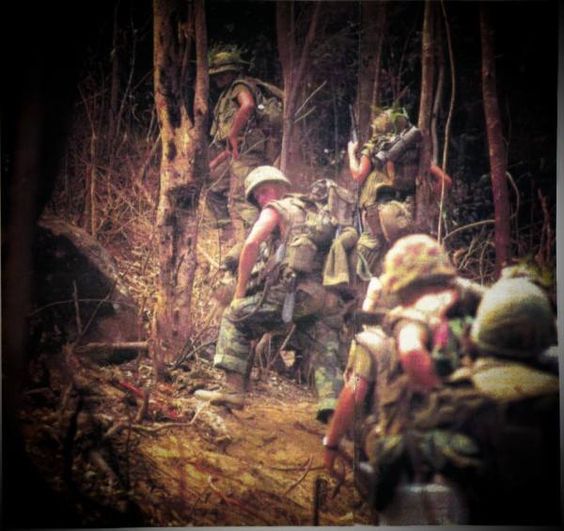

The RRF was ordered to move at 7:35am. Using the speed and shock effect of the Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs), the Spanish moved fast, using the vehicles as battering rams against their enemy. Nine vehicles were scrambled together to load up the soldiers and, 25 minutes later, the M113s were roaring down the road. They were ambushed on the edge of the Loa Hong village, just a few miles to the north of My Tho. The enemy had set an ambush against the expected Spanish force, but they were quickly dispersed by the APC’s mounted guns and the RRF pressed forwards. Two hours later their advance came to a brutal stop when thet were ambushed again and immediately peppered with sniper fire. As the Spanish soldiers sprung from the relative safety of the vehicles, they took up defensive positions in the roadside monsoon drains and behind walls. Soon semi-automatic fire and rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) racked the area, to which the Spanish soldiers responded with rifle and machine gun fire.

The initial reports proved to be wrong and the "just two enemy platoons" turned out to be at least two companies of local guerrillas. Soon, the Spanish force was force to withdraw, fortifiying themselves in an US Administration and Logistics Compound that housed the Provincial Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) and the staff bungalows. The APCs provided invaluable support to the infantry with their firepower. The use of heavy weaponry was discounted due to the potential risk to civilians in the up area.

In this confused situation, the RRF began to clear and occupy the nearby houses on both sides of the road. When the soldiers asked how to do that, an enraged and surprised major Henriquez shouted at them: “Just use your grenades and go in after them!”. Some soldiers, though, later remebered that their CO had not mentioned any grenade at all but their balls. To this day, this version remains unconfirmed.

So, the Spanish group moved slowly, being supported by an APC until it came under attack when it pulled into a narrow street where it was fired on from the surrounding houses. The aggressive VC soldiers threw grenades over the walls and fired RPGs at will, spreading large amounts of debris for its scattering shrapnel effect. However, little by little the enemy soldiers were forced to withdraw and around 10 am the other sections moved to consolidate. By 11 am the area was secured and the VC remnats withdrew. Once the final casualty was evacuated, the RRF returned to its base with M113 damaged but still in working order.

However, in spite of the enemy withdrawal, the Spanish solider could hear a Vietcong bugler as whistles blew out at night. As that sounded as a potential battalion size attack, the Spanish became an all-time Stand-To during the whole night. In retrospect, Major Henriz thought that the bulk form of the APCs and their noises may had deterred the enemy, who possibly mistook them for tanks. The situation remained static through the night except for occasional sniper fire and a number of RPG rounds. All in all, the night went without serious incident.

Skirmishes and some heavy actions took place in surrounding villages during the following days until the 8th of February.