You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Es Geloybte Aretz - a Germanwank

- Thread starter carlton_bach

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Whew, finally. Sorry for the long gaps, I'm getting married this week and it's kinda busy.

Congratulations! Many happy years.

Thanks all of you. I'm a very lucky guy, really.

And shortly, there should be news from the assault on Kilwa and the second battle of Lublin.

And shortly, there should be news from the assault on Kilwa and the second battle of Lublin.

23 March 1907, Moscow

The hushed silence of scurrying servants and stunned courtiers was broken by the click and jingle of cavalry boots on the polished parquet floor: Grand Duke Nikolai had arrived. Relief washed over Count Fredriks as he heard the familiar voice of the only man who could, at times like these, touch the Czar.

“Where is he?”, the grand duke asked without bothering with preliminiaries.

“In his apartments, Your Highness.” the minister of the court replied with a quick, elegant bow. “Ever since he heard the news, His Majesty has withdrawn. The Empress Alexandra and Dr Dubrovin are with him.”

Nikolai snorted. Dubrovin! That damned poisoner of words, that carrion-crow of a court parasite latching onto the vulnerabilities of his cousin! How like him it was to be with the Czar in such an hour, to offer his support, ingratiate himself, make himself indispensible. Alexandra would hardly help, either. As far as the grand duke was concerned, the woman was religiously mad. Her conversion to orthodoxy had been ridiculously complete. She had been devoted to Prokurator Pobedonostsev, if anything, even more than her husband, and the news of his death, though hardly unexpected, must have hit her very badly.

“He has ordered a state funeral.” Fredriks spoke again. “Three days from now, with full honours and the guards cavalry in attendance. I'm not sure...”

Nikolai did not envy the poor man his duties. Most of the guards cavalry was in East Prussia – the parts of it that still existed, anyway. The garrison in Moscow was sizeable, but not enough for the pomp and circumstance that Nicholas had to be envisioning. Of course Count Fredriks wouldn't be telling him that – that happy lot would fall to a senior cavalry officer, and guess who had just happened to walk in? Sometimes, a front command looked downright inviting by comparison to the snake pit the Kremlin was becoming.

The tap nof crutches down the hall signalled the arrival of Grand Duke Sergei, accompanied by two bodyguards. You hardly ever saw him without his twin cossacks, one at each side. Their main function was to prevent him from falling if he tripped up or his legs betrayed him, something that happened increasingly often and elicited outbursts of irrational anger. Nikolai occasionally wondered if Sergei resented him for being whole and athletic. The attack could have struck him just as easily, after all.

“Nikolai.”, he exclaimed. “You've heard, too, no doubt.”

News of Pobedonostsev's death had travelled fast. The court was buzzing with speculation about his successor already, both in the position of Procurator of the Holy Synod and in the Czar's favour.

“I came to see Nicholas.” the grand duke explained himself,. More defensively than he had intended. “The news must have come as a blow.”

The two met, stiffly, at the door of the imperial apartments, plumed guards standing to attention as they passed. Nikolai turned the handle and found it locked. He called out for a servant to open it. The wait lengthened embarrassingly as the soldiers stared fixedly forward. Footsteps behind the door announced someone's arrival.

“His Majesty is seeing nobody.” the voice behind the door announced. “He is in mourning and praying for the soul of his most trusted advisor.”

Sergei looked up in astonishment. “Dubrovin!” he mouthed silently. Nikolai nodded. “This is Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich come to see the Emperor!” he called out at the door, with little hope of getting a response. Imperial authority and all, but this was ridiculous.

“I am sorry, Your Highness,” the answer came, “but the Czar's wishes are clear. He will not be seeing anyone at this time,. I will convey your condolences.”

“Condolences, my ass.” Sergei burst out in a hissing whisper. “He's hiding.” His face was flushed with anger, his knuckles white gripping the carven ivory handles of his crutches.

“I know.” Nikolai shrugged. “And there really isn't anything we can do about it. I'm sure he will see us later.” He hesitated. It had been over a year since he had exchanged more than a few words with Sergei. Maybe this was the opportunity to try and heal their rift? Or at least to clear up where they stood. He cleared his throat.

“Don't you have apartments in this wing?” he asked. “It would be convenient if we could wait there.”

Grand Duke Sergei paused and nodded. “Come along.”, he said. “I'll order us tea. There are a few things I've been meaning to discuss with you.”

24 March 1907, Lodz

“So, you intend to be our Hearst, then?” General Ferber asked the bespectavcled young man seated across his desk. He had learned a lomg time ago not to rely too much on first appearances, but in this case itz was almost ridsiculously difficult not to.

“Not a Hearst.” Moisei Uritski said. “Maybe your Ullstein. Or maybe more your Hugenberg. I propose you help and coordinate the efforts of Jewish papers, and they can certainly use the help.”

“As, no doubt, can you.” Ferber retorted, pointing at the threadbare coat and scuffed shoes of his petitioner. “You are asking a lot of money for this, and I'm not sure I can give it to you.”

“Not that much. You can probabnly get it from donors, anyway, you won't need to take it out of your military funds.” Uritski took his glasses off and began polishing the lenses. “Most edsitors don't ask for much. A few storioes from the international press, translated into Yiddish, enough to eat, a few pennies for their reporters. And it will give you a great advantage. Can you imagine what a united Jewish press would have meant during the Garski trial?”

Ferber scratched his chin. That much was true. Poland was still a pretty inchoate place, and most of the time even people who read the foreign press – a luxury at the best of time – had almost no idea what was going on over the next hill. The Army Council sent out communiques, but he knew well enough how those were produced now. A real press – that would be worth having. And the German donors were generous enough.

“I will talk to Rabbi Landauer.” he said., “No promises. But I do think your idea has merit. Draw me up a plan of what you want to do in the next few months, will you?”

Uritski smiled. “No problem, general. You can have it on your desk tomorrow. In the meantime – any chance of getting quarters?”

Ferber hesitated. Living space did not grow on trees in war-scarred Lodz. On the other hand, Uritski did make sense. “All right.” he said, ringing the bell on his desk. An orderly entered the room. “Sergeant, find Mr Uritski a bed somewhere. A room, if you can. He may be staying for some time.”

25 March 1907, Kilwa

Lindi harbour

Lindi harbour

“The health benefits alone will be tremendous.”. Lieutenant Chekov pointed out. “A lot of the men don't react well to tshombe beer. And I have to say, neither do I.”

The officers seated around the table nodded, shuddering at the thought of the rank, sickly-sweet stuff they drank by filtering it through clenched teeth. The consignment of potato spitit that had been intercepted on a dhow coming down the coast was a godsend, and being denominated German, it didn't even need paying for.

“I'm certain the men will appreciate the rations. It's not proper vodka, but certainly better than tshombe.” Lieutenant Commander Frelikh agreed. “And we have how much of the stuff?”

“Twenty tons, give or take.” Chekov reported. ”Some is bottled, but most is in casks. It's all German-made, Woermann goods. We intercepted it on a ship from Zanzibar – the first nigger-crewed keel I'vew ever seen with proper cargo documents. I guess the Germans will teach a monkey proper paperwork given enough time.”

Frelikh smiled. “We may want to inform Admiral Witgeft of the haul.” he pointed out. “The rest of the fleet is no doubt also interested in getting a proper issue.” He did a quick calculation. A 50-gramme ration for ten thousand men would come to half a ton – poor prospects for thirsty sailors if their catch would be gone in less than a month. “But not immediately.”, he added. “Issue 100 grammes per man today. I hope the stuff is good.”

Chekov nodded. “It's damned good. Labelled 35% by volume, proper.”

“That's pretty weak.” Frelikh ordered “150 grammes then.” He picked up the glass on the table and sipped. It was not bad, if you made allowances for the fact that it was export rotgut intended for sale to savages. Kicked like a mule, too. Lieutenant Commander Frelikh wondered idly how honest Russian manufacturers were with their alcohol contents. 35% vodka certainly did not feel like this at home.

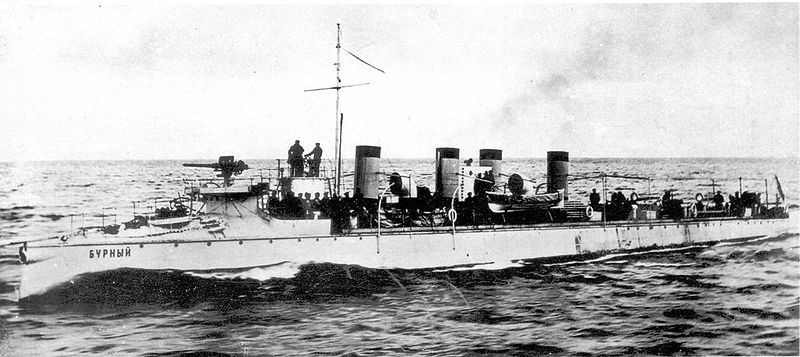

The officers filed out of the low-ceilinged harbourmaster's office. Frelikh waved to his boat crew to take him back to his command. The destroyer Boikiy might be cramped and already unbearably hot, but it was still preferable to the sticky mists on the shore. He would have the sunscreens doused in seawater. Cheering from the improvised barracks told him that word had spread.

“You can tell the men, Bugaiev,” he instructed his coxswain in passing, “there'll be a proper vodka ration today. You can thank the patrol pinnace.”

Last edited:

Well, I'm suspicious that's the case too.

But on the other hand, this makes sense. Give a bunch of soldiers with low morale a gigantic cargo of vodka, what follows should be obvious.

I'm still leaning towards "massive coincidence" though.

In this case, a telegraphic order through a friendly merchant in British-controlled Zanzibar. It's amazing how long you have to cruise offshore until the patrol boat finds you. Sometimes, German intelligence work is that good.

26 March 1907, Lindi

By the roadway outside the town

Guardpost on the coastal road

By the roadway outside the town

“Still nothing?” Major Johannes trained his field glasses on the Russian fieldworks, a guardpost on the dusty road leading away into the woods that now concealed his advance guard.

“Nothing.” Sergeant Abderrahman confirmed. “A few lights, but no activity. They haven't noticed.” The white teeth of his feral smile gleamed in the night.

“All right. We begin attacking on the prearranged signal. Keep the damned rugaruga under control until then!” The major checked his watch for the umpteenth time, wishing there was a way to tell the time that did not involve pulling it from his breast pocket and dangling it in front of a hooded lantern. Everybody should be in place by now. Patience. And pray nobody pulled anything stupid. Ten minutes – he would allow Abderrahman that much to get back to his command. Pacing, he checked again that No 1 machine gun was as ready as it had been fifteen minutes ago. One of the farmers looked up and attempted a salute, his enormous rifle sticking up into the air at a ridiculous angle. He put the major in mind of the huntsman from the Struwwelpeter stories.

“Time.” A guick gesture to his German NCO, and the lantern was quickly unhooded for a rapid succession of blinking signals. Still nothing. Right now, out there, rugaruga would be creeping through the brush, closing in on the guardpost. Minutes crept by with agonising slowness.

Guardpost on the coastal road

Sergeant Garyshkin was not an unreasonable martinet. He certainly was not going to begrudge his men their recreation. But what he found inside the machine gun emplacement was too much. His boot connected harshly with the leg of a sleeping soldier.

“Get the fuck up, you idiot!” he shouted. “What do you think you are doing?”

Two riflemen, stripped to their undershirts, were seated at a table playing cards. Neither of them were placed to overlook the road. “Fucking get your guns, dammit!”

Grumbling, they obeyed, their movements slow and awkward. It had to be the vodka. They weren't used to it any more. Garyshkin could feel the lightness in his own head.

“Remember what happened at Kilimatinde? Damn you, there could be some nigger warrior sitting out right there in the bush waiting to cut your fucking dicks off! What'll you do then?”

The sergeant unhooked a kerosene lamp and pointed outside to illustrate his claim – and froze face to face with a Wayao warrior. The shock paralysed both for an instant, but military-honed reflexes won out. Garyshkin's rifle barked as the rugaruga was still raising his. The man fell, a gaping hole in his chest. “SHIT!”

The guards stared, open-mouthed. The sudden muzzle flash illuminated several more men rising from the grass or hunched along the road. Men with clubs, spears and rifles. The sergeant screamed at them to man the machine gun, frantically working the lever of his Nagant . Gunfire flashed in the dark, capturing almost photographic still frames of a shifting scene filled with more and more black bodies.

The machine gun sputtered to life, the assailants hitting the dirt. Garyshkin grunted – there was hope. Fumbling, he reloaded and fixed his bayonet. Things might well get ugly before enough reinforcements came up. He stared out into the gathering morning light, seeking out targets. A man with a shield, standing up. Bang! Gone. He trained left and right, trying to spot the next enemy. Another spearman, frighteningly close, firing a Mauser rifle with one hand. Bang! Missed – the man was cut down by a machine gun burst before the sergeant could fire again. Then, the forest's edge erupted in hundreds of points of light. It took Garyshkin a moment to realise he was looking at rifle fire. He never saw the war club that caught him from behind as the rugaruga swarmed the defenses, tangling with the riflemen now running up.

On board destroyer Boikiy

In the dark armpit of a tropical night, Lieutenant Commander Frelikh had on occasion dreamed nightmares like this. Dragged from his cot, eyes sticky and bleary from his fitful sleep, head throbbing with drink, he found himself taking the bridge in his shirt and underpants, trying to make sense of the chaos unfolding around him. Gunfire from the shore had roused the watch, and Ensign Chekov had taken the ship inshore to support the defenders once a messenger had brought the news of the German assault. The blast from the bow gun sounded ridiculously inadequate, but the shells still had sent men tumbling right and left when the enemy had reached the beach. At least they had hoped they were enemy troops.

Then, the boats started swarming. The gunners were still targeting the dark silhouettes of riflemen ducking behind windows and flat roofs peppering them with bullets when the first pirogues moved in on them. Frelikh had barely noticed them in time, screaming at the sailors to fire at them. He felt the engine come to life slowly – far too slowly – the steam gradually rising. Why had he ordered the fires banked!? The discomfort of the heat was nothing compared to the mortal danger he had placed everyone in. Rifles cracked, a machine gun chattered. Three sailors fell from the stern deck, Frelikh tried to spot the gun position on the shore. The customs house! He frantically pointed it out to the gun crew, two shells going wide, the third striking home. The roof fell in.

“How soon until we have full power?” he shouted down the speaking tubes. “Give me speed!”

He had to outrun the boats. Once the boat had power, he could run rings around them, ram them, plough them under. Sitting in the middle of the harbour picking them off one by one wouldn't work. They had to only get lucky once. Panicked screams and cries of agony showed him – too late – that they had been lucky. Enemy warriors had boarded Boikiy over the fantail, swarming out spearing and shooting sailors. Frelikh grabbed Chekov and pointed him there. The young man waved to a knot of sailors and moved forward to repel the enemy, a revolver in one hand, a wrench in the other. It looked like something out of the age of piracy. Fascinated by the spectacle astern, Frelikh briefly stood motionless. Men were screaming, stabbing, shooting and dying,. Sailors emerged from hatchways, gunning down attackers, and the boarders fired their rifles down every hatch and porthole they could find. It was a hopeless undertaking. The Russians' superior fire discipline and weight of numbers told, and the last of the African went overboard, clutching a deadly wound to his stomach. Frelikh took a close look at the jabbering, near-naked figures armed with spears, shields and old rifles. He resolved he would rather die than fall into the hands of these cannibals.

“How much longer till we have power?” he yelled. No answer. He looked back: black smoke was pouring from aft portholes. Something had caught fire in the fight! “Damage control!” he shouted, coughing. “Firefighters aft!” The gun crew was still firing, blindly now, he was almost sure. Bullets spanged off the ship's hull. The helmsman had slumped over the wheel, a jagged red hole open in his side. Frelikh levered the body away from the spokes, grasped the helm and yanked the handle of the engine order telegraph to full ahead. The screw still turned sluggishly, but she was answering the rudder. Head for the high seas. Get away from the shore. If she could just keep going for a few more minutes, they would be safe!

Lindi harbourmaster's office

Major Johannes' eyes, burning from cordite smoke and dust, still had light spots dancing in front of them as he tried to focus on the spot in the harbour where the Russian ship had been. Debris was bobbing on the roiling waters now, the bow of the ship quickly disappearing. The explosion was still echoing over the city, now a bacchanal of riotous looting and celebration.

“Why didn't they strike?” the major said to nobody in particular. The second Russian ship was now standing out to sea, waiting outside of gun range. A steam pinnace apperoached the port.

“Sir!” Lieutenant von Johns pointed out, “they are moving within range. We can hit them.”

Major Johannes, still trying to focus, raised his field glasses. “No.” he said curtly. “They are picking up survivors. Let them.”

Closer inshore, a handful of rugaruga had secured one of the few rirogues not capsized by the force of the blast and were paddling out, spears ready, to hunt Russian swimmers. Johannes retched.

“Sergeant Abderrahman!” he ordered.

“Sir?” The huge askari appeared at his side almost immediately.

“Take your men and kick the damned rugaruga back into shape. I won't have this kind of behaviour.”

Abderrahman saluted and trotted away, bellowing orders in Swahili. Major Johannes walked over to where Russian shells had pulverised the mud brick wall, killing two riflemen who had sheltered behind it. A bottle rolled in front of his feet, empty, the label saying “Kartoffelbranntwein, 35% vol”. He kicked it away. The props had served their purpose. He would need to remember to have the askari secure the casks, if they were still in one piece.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: