Seven Days' Battles (June 25 - July 1)

A grueling series of battles over the course of seven days, giving the series of fights its collective name in the history books. Union General George McClellan and his troops faced off against General Robert E Lee in seven places:

Oak Grove

Major General McClellan advanced his lines, hoping to bring Richmond within range of his siege guns to end the war by capturing the Confederate capital. Two Union divisions of III Corps attacked across the headwaters of White Oak Swamp, but were repulsed by Confederate Major General Benjamin Huger's division. While he was 3 miles to the rear, McClellan telegraphed ahead to call off the attack, but when he arrived at the front, ordered another attack. Only the darkness of the sunset halted the fighting. His troops gained only 600 yards, at a cost of over a thousand casualties to both sides.

Mechanicsville

The battle near Mechanicsville was to be the start of Confederate General Robert E Lee's counter-offensive against the Army of the Potomac, but his attempted turn on the Union's right flank, which was north of the Chickahominy River failed due to Maj. Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson arriving about 4 hours late. He and his troops were fatigued due to his lengthy and arduous Shenandoah Valley Campaign, but the campaign was ultimately successful in preventing reinforcements to McClellan.

By 3 PM, A.P. Hill grew impatient and began his attack without orders from Lee, a frontal assault with 11,000 men. Porter extended and strengthened his right flank, and fell back to concentrate along Beaver Dam Creek and Ellerson's Mill. They would encounter 14,000 well-entrenched Union soldiers, aided by 32 guns in six batteries, which would turn back the repeated Confederate attacks with heavy casualties.

Jackson had arrived late in the afternoon and ordered his troops to bivouac for the evening, while the major battle was happening within earshot. His presence did cause McClellan to order Porter to withdraw, fearing a threat to his supply lines, which caused McClellan to shift his base of supply to the James River. Again, McClellan feared he was seriously outnumbered due to the diversions by Huger and Magruder. He told Washington he faced 200,000 Confederates, not 85,000 that were actually there. His decision meant McClellan would abandon the siege of Richmond. This would be a tactical Union victory, with the Confederates gaining none of their objectives due to the flawed execution of Lee's plan. He fielded only 15,000 instead of 60,000 men crushing the enemy flank. Despite their success, this would be the beginning of a strategic Union debacle where McClellan never regained the initiative.

Gaine's Mill

Following the inconclusive battle of the previous day, General Lee renewed his attack on the right flank of the Union army, which was relatively isolated on the northern side of the Chickahominy River. Union Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corp had established a strong defensive line there behind Boatswain's Swamp. Lee decided to launch the largest Confederate offensive attack of the war, with about 57,000 men in six divisions. Porter's reinforced V Corp held fast for the afternoon as the Confederates attacks in a disjointed fashion, first with Maj. Gen. AP Hill's division, then Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell's, both suffering heavy casualties.

Unfortunately Maj Gen Jackson's command was delayed, preventing the Confederates from concentrating their force before Porter got his reinforcements from VI Corps. Due to his exhaustion, his commands were garbled and one of his staff, Major Robert Dabney, had to correct the orders to make sure they were understood.

By dusk, the Confederates finally mounted a coordinated assault which broke Porter's line, and drove his men back toward the river; they would retreat across the river during the night, but the Confederates were too disorganized to pursue them. The defeat here schocked McClellan such that he abandoned his attempt to capture Richmond, saving the capital of the Confederacy for now. McClellan began a retreat to the James River.

Garnett's and Golding's Farm

While the main forces were battling north of the Chickahominy River, Confederate General John Magruder was conducting a reconnaissance in force, which developed into a minor attack against the Union line south of the River at Garnett's Farm. His Confederates attacked again near Golding's Farm on the morning of the 28th, but were repulsed in both cases, but not before causing over 200 casualties to the Union troops. Magruder's attacks accomplished little other than convincing McClellan that he was being attacked from both sides of the river.

Savage's Station

The majority of McClellan's army had concentrated around Savage's Station on the Richmond and York River Railroad, preparing for a difficult crossing through and around White Oak Swamp. It did so without centralized direction because McClellan had personally moved south of Malvern Hill after Gaines's Mill without leaving directions for corps movements during the retreat, or naming a second in command in his place. Clouds of black smoke filled the air near the station as the Union troops were burning anything they could not carry. Morale dropped, especially for the wounded, who realized they weren't being evacuated along with the rest of the army.

General Lee devised another complex plan to pursue and destroy McClellan's Army. While Maj. Gens. Longstreet and A.P. Hill's divisions loved back toward Richmond, then southeast to the Glendale crossroads, and Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes's division headed further south to near Malvern Hill, Brig. Gen. John Magruder's division was ordered to move east along the Williamsburg Road and the York River Railroad, to attack the Federal rear guard. Stonewall Jackson, commanding his own division, along with those of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill and Brig. Gen. William Whiting, was to rebuild a bridge over the Chickahominy, then head due south to Savage's Station, where he would link up with Magruder, to deliver a strong blow that might cause the Union army to turn around and fight during its retreat.

Again, Jackson's orders were garbled, and he initially thought he was to stay and guard the bridge, but he had the orders repeated, and showed up to link up with Magruder, late, but he showed.

The Confederates managed to attack and smash the Union troops, who fought as they retreated. The rear guard absorbed the brunt of the Confederate attack, and Jackson's arrival helped ensure an actual Confederate victory, though costly, at roughly 600 casualties to the Union 1700 casualties.

Glendale

The divisions of Confederate Major Generals Ben Huger, James Longstreet, and A.P. Hill converged on the retreating Union Army, near Glendale (also called Frayser's Farm). Longstreet's and Hill's attacks penetrated the Union defenses near Willis Church. Union counterattacks sealed the break, and saved their line of retreat along the Willis Church Road. Huger's advance was stopped on the Charles City Road. Maj. Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's divisions were delayed by Union Brig. Gen. William Franklin's corps at White Oak Swamp, preventing him from joining up with the rest of the Confederate army. Confederate Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes made a poor attempt to attack the Union left flank at Turkey Bridge, but his forces were driven back. Had his forces been more coordinated, Lee could have cut off the Union army from the James River. The Union army set up a strong position on Malvern Hill that night.

Malvern Hill

The Union's V Corps had taken up positions on June 30, under the command of Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter. McClellan had already at this point boarded the USS Galena, an ironclad, and sailed down the James River to inspect Harrison's Landing, where he intended to locate the base for his army. Fortunately for the Confederates, they had good maps of the area, letting Confederate Maj. Gen. John Magruder arrive in time for the battle, and letting both Maj. Gens. Benjamin Huger and Stonewall Jackson collect artillery successfully to be present for the battle.

The issue with the battle was a series of blunders in planning and communication on both sides, which were only corrected by the afternoon, during the third Confederate charge, when they were finally supported by artillery. They faced thrice the number of Union artillery batteries, though, but were able to inflict casualties on the Union infantry and artillery entrenched there. Unfortunately, the Union troops did manage to inflict heavy casualties on the Confederates.

The Union troops evacuated and the Confederates returned to Richmond, the threat to their capital ended. Lee was hailed as a hero in Richmond's three newspapers.

Jackson argued against a direct attack, and proposed turning to the Union eastern flank. Walter Taylor and Porter Alexander both thought they should occupy Evelynton Heights with all the artillery, but Lee's attention was focused on the retreating Union army. D.H. Hill tried to talk Lee out of canceling the attack or finding another route, but Lee ignored him. Lee still maintained the belief in a headlong attack, which had caused and would continue to cause massive casualties to the Confederates and Union troops as well.

D.H. Hill wrote of the battle, "It was not war, it was murder." Had Lee coordinated artillery and infantry, rather than the piecemeal attack, perhaps more lives could have been spared.

Commanders:

Union: George B McClellan

Confederate: Robert E Lee

Armies:

Union: Army of the Potomac

Confederate: Army of Northern Virginia

Strength

Union: 114,691

-Army of the Potomac: 105,445

-Dix's Division: 9,246

Confederate: 92,000

Union Casualties:

Killed: 1,864

Wounded: 8,114

Captured/Missing: 6,098

Confederate Casualties: roughly 18,600 total

Based off the performance here, General Lee reorganized his army into two corps, led by James Longstreet and Thomas Jackson, and removed several generals who performed poorly during the fighting.

A Letter to Davis

General Jackson wrote to President Davis, urging him to bring the war to the northern people to make them end the war sooner. The South did not have as many people to lose as the North, he wrote, and could not overwhelm the Union armies as they could the Confederate armies. He asked his friend Alexander Boteler on July 7 to plead with the President. Boteler asked Jackson why he didn't present the idea to Lee; Jackson did, but Lee said nothing. Boteler presented the idea again to Davis, who declined again, believing that the North would soon tire of the war and quit.

Battle of Second Manassas (August 28-30)

After the failure of Maj. Gen. George McClellan's Peninsula Campaign in the Seven Days Battles back in June/July, President Lincoln appointed John Pope to command the newly created Army of Virginia. He had some success in the Western Theater of the war, and Lincoln sought a more aggressive general than McClellan.

Pope's mission had two main objectives: Protect Washington DC and the Shenandoah Valley, and draw Confederate forces away from McClellan by moving in the direction of Gordonsville. Based on his experience in fighting McClellan, General Lee believed that McClellan was no further threat on the Virginia Peninsula, so he didn't feel the need to keep all his forces in direct defense of Richmond. This allowed him to move Jackson and his command to Gordonsville to block Pope and protect the Virginia Central Railroad. Lee had even bigger plans than just blocking Pope. Since the Union army was split between McClellan and Pope, and widely separated, Lee saw a chance to destroy Pope before returning his attention to McClellan and his army. He ordered Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to join Jackson with 12,000 men to accomplish this.

From the 22nd to 25th of August, both armies fought a series of minor skirmishes along the Rappahannock River. Heavy rains swelled (swoll) the river and Lee couldn't force a crossing. By this time, reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac were arriving from the Peninsula, where they were evacuating. Lee's new plan to face all these forces which were outnumbering his army was to send Jackson and Stuart with half the army to make a flanking march to cut off Pope's line of communication (the Orange & Alexandria Railroad). His hope was to force Pope to retreat, and that he could then be defeated while moving and vulnerable. Jackson reached Salem that night.

On the evening of the 26th, after passing around Pope's right flank via the Thoroughfare Gap, Jackson's wing of the army struck the railroad at Bristoe Station, and before daybreak on the 27th, marched to capture and destroy the massive Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. Jackson's surprise movement forced Pope into an abrupt retreat from his defensive line along the Rappahannock. Then, during the night of the 27th-28th, Jackson marched his divisions north to the First Manassas battlefield, where he took position behind an unfinished railroad grade below Stony Ridge. It was a good defensive position. The heavy woods allowed his Confederates to conceal themselves while maintaining good observation points on the Warrenton Turnpike from there, which was the likely avenue of the Union movement, only a few hundred yards to the south. There were good approach roads for Longstreet to Join Jackson or for him to retreat to the Bull Run Mountains if he couldn't be reinforced in time. Last, the unfinished railroad grade offered cuts and fills that could be used as ready-made entrenchments.

In a minor Battle of Thoroughfare Gap on the 28th, Longstreet's win broke through light Union resistance and was able to join Jackson. This tiny skirmish essentially ensured Pope's defeat, since it allowed two wings of Lee's to unite on the Manassas battlefield.

First Day of Battle, August 28th

The Battle of Second Manassas began August 28th, when a Federal column under observation by Jackson just outside Gainesville, near John's Brawner family, moved along the Warrenton Turnpike. The Union column consisted of units from Brig. Gen. Rufus King's division (the brigades of Brig. Gens. John Hatch, John Gibbon, Abner Doubleday, and Marsena Patrick), marching eastward to concentrate forces with the remainder of Pope's army at Centreville. King was not with his division because he had suffered a serious epileptic attack earlier in the day.

Jackson, who had been informed Longstreet's men were on their way to join him to his relief, displayed himself prominently to the Union troops, but his presence was disregarded. As he was concerned that Pope might be withdrawing his army to link up with McClellan's forces, Jackson determined to attack the Union troops. Returning to his position behind the tree line, he told his subordinates, "Bring out your men, gentlemen."

At about 6:30 PM, Confederate artillery began shelling the portion of the Union column to their front, John Gibbon's Black Hat Brigade. Gibbon was a former artilleryman, and he responded with fire from Battery B, 4th US Artillery. The artillery exchange halted King's column. Hatch's brigade got past the area, while Patrick's men in the rear sought cover, leaving Gibbon and Doubleday to respond to Jackson's attack. Gibbon assumed Jackson was at Centreville, and these were just horse artillery from J.E.B. Stuarts cavalry. He sent aides to the other brigades for reinforcements, hoping to capture the guns. He got his staff officer Frank Haskell to bring the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry to disperse them. He met the 2nd WI in the woods, telling them, "If we can get you up there quietly, we can capture those guns."

Under Col. Edgar O'Conner, the 2nd WI advanced obliquely through the woods that the Union army was passing through. They were able to drive back the Confederate skirmishers, but soon received a heavy volley on their right flank by 800 men of the Stonewall Brigade under Col William Baylor's command. Absorbing the volley from 150 yards, the 2nd WI didn't waver, but replied with a devastating return volley at the Virginians in Brawner's orchard. The Confederates returned fire when the two sides were only 80 yards apart. As units were added by both sides, the battle lines remained close together, with little cover, trading volleys for over two hours. Gibbon added his 19th Indiana (IN); Jackson, personally directing the actions, sent 3 GA regiments belonging to Brig Gen Alexander Lawton's brigade. Gibbon countered with the 7th WI; Jackson ordered Brig Gen Isaac Trimble's brigade to support Lawton, which met Gibbons' last regiment, the 6th WI.

After Trimble's brigade entered the fight, Gibbon needed to fill in a gap in his lines, and got the 56th PA and 76th NY, who advanced through the woods and checked the Confederate Advance. These men arrived on the scene after dark, and both Trimble and Lawton launched uncoordinated assaults against them. Horse Artillery under Captain John Pelham were ordered forward and fired at the 19th Indiana from less than 100 yards. Doubleday's regiments retired to the turnpike in an orderly fashion. The first day was a stalemate for the most part, with 1350 Union and 1250 Confederate casualties. The 2nd WI lost 278 of 430 engaged. The Stonewall Brigade lost 240 of 800. Two GA regiments - Trimble's 21st and Lawton's 26th - each lost more than 60%. One in three men were shot in the engagement. Confederate Brig. Gen. William Taliaferro wrote, "In this fight there was no maneuvering and very little tactics. It was a question of endurance and both endured." Taliaferro was wounded with a flesh wound, as was Ewell, whose left leg was nicked by a Minié ball, nearly removing him from action by amputation had it been only an inch to one side.

Jackson did not achieve a decisive victory with his superior forces (6200 to Gibbon's 2100) due to the darkness, piecemeal deployment off forces, and the tenacity of the enemy. But he did get the strategic intent, attracting Pope's attention, and learned from the experience. Pope thought he was retreating and sought to capture him before Longstreet could reinforce him. Pope issued orders to his subordinates to surround Jackson and attack him in the morning, but Jackson was not where Pope thought he was, and his own troops weren't where he assumed. He thought McDowell and Sigel were blocking Jackson's retreat westward, but King and Rickets had both retreated south, and Sigel and Reynolds were both south and east of Jackson, who had no intention of retreating, waiting for Longstreet's arrival.

August 29

Jackson had initiated the attack at Brawner's farm, with the intent of holding Pope till Longstreet could arrive with the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet's 25,000 men began their march at 6 AM on the 29th. Jackson sent Stuart to guide the initial elements of Longstreet's column into positions Jackson had preselected for the fight.

While he awaited the troops, Jackson reorganized his defenses in case Pope attacked him in the morning, positioning 20,000 men on a 3,000 yard line, south of Stony Ridge. Noticing the build-up of the I Corps (Sigel) troops along the Manassas-Sudley Road, he ordered A.P. Hill's brigades behind the railroad grade near Sudley Church on his left flank. Being aware that his position was a little geographically weak, since the heavy woods prevented effective artillery deployment, Hill put his brigades in two lines, and Jackson put two brigades from Ewell's division (temporarily under Brig Gen Alexander Lawton while Ewell rested his wound), and on the right, William Taliaferro's division, commanded by Brig. Gen. William Starke.

Jackson's position straddled a railroad grade, dug out by the Manassas Gap Railroad Company in the 1850s, and abandoned just before the war. Some parts were a good defensive position, and others were not. The heavily wooded terrain largely precluded the use of artillery other than at the right end of the line, which faced open fields. The Confederate right flank, held by Taliaferro's (Starke's) division was potentially vulnerable as that was the smallest of Jackson's divisions, so he put the brigades of Early and Forno, both of which had not been engaged last night. They would also watch and give notice of Longstreet's arrival.

On daybreak on the 29th, Pope learned that Ricketts and King had both withdrawn to the south, and Gibbon arrived in Centreville telling Pope the retreat was a mistake, despite the fact that he had recommended it, and he had no idea what became of McDowell. Gibbon rode down to Manassas and found Porter's troops resting and drawing rations, while King had turned over command to John Hatch due to his epileptic attacks making him ill. McDowell was also there, having spent most of the prior day wandering aimlessly around Prince William Country. Pope was still convinced that Jackson was in a desperate situation and almost trapped, but his assumption, besides being incorrect, depended on the coordination of his troops, none of which were where he needed them to be.

The end result of his situation was that Pope's complicated attack plans for the 29th ended up being a simple frontal assault by Sigel's corps, the only troops in position that morning. Many thought his corps was one of the army's weak links; though Sigel was a trained and experienced military officer, he was seen as an inept political general. A large portion of his men were German immigrants, suffering from prejudices, and had performed poorly in battles against Jackson in the Shenandoah during the spring. Until Pope himself arrived, Sigel was the ranking officer in the field and would be in command.

Pope intended to move against Jackson on both flanks. He ordered Fitz John Porter to move toward Gainesville, and attack what Pope considered the Confederate right flank. Sigel was to attack Jackson's left at daybreak. Since he was unsure of Jackson's dispositions, he chose to advance on a broad front, with Brig. Gen. Robert Shenck's division, supported by Brig. Gen. John Reynold's division on the left, Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy's brigade in the center, and Brig Gen Carl Schurz's division on the right. Schurz's two brigades were the first to make contact with Jackson's men about 7 AM.

Though the unfinished railroad grade provided a good natural defensive position in some places, the Confederates eschewed static defense, absorbing Union blows and following up with vigorous counterattacks (The same tactics Jackson would later use at Antietam in a few weeks). Schurz's two brigades (under Brig. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig and Col. Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski) skirmished with Confederates Gregg and Thomas, both sides committing forces piecemeal. Hand to hand combat took place in the woods west of Sudley Road, with Krzyżanowski's brigade and Gregg's. Milroy heard the sound of battle to his right, and ordered his brigade forward, the 82nd OH and 5th WV in front, and the 2nd WV and 4th WV in the rear as support.

The two forward regiments immediately met volleys of Confederate musket fire, and in the confusion, the 82nd OH found an undefended ravine in the middle of the railroad embankment, getting to the rear of Trimble's Confederate brigade. Unfortunately for them, Trimble was quickly reinforced by part of Bradley Johnson's Virginia brigade, and the 82nd OH was forced to retreat. Its commander, Col James Cantwell, was shot dead and his regiment fled in panic, causing the 5th WV behind them to retreat in disorder also. In just 20 minutes, Milroy's brigade had taken 325 casualties. Shcenck and Reynolds, under heavy artillery barrages, countered with their own artillery, but avoided advancing their infantry, instead just using skirmishers, who got into a low-level firefight with Jubal Early's brigade.

While this action was taking place, Meade's brigade came across wounded men from King's division who had been abandoned by their comrades and left on the field all night. Medical personnel attempted to evacuate as many as possible under the ongoing firefight around them. Milroy attempted to rally the survivors even though his own brigade had been destroyed; he came across Brig. Gen. Julius Stahel, one of Schneck's brigadiers, and ordered him to defend against any Confederate counterattack from the woods. About a hundred or so Confederates soon came out of the woods in pursuit of Milroy, but were quickly driven back by artillery fire, and Stahel returned to his original position south of the turnpike.

Schurz assumed that Kearny's division of the III Corps was ready to support him, and ordered another assault against Hill around 10 AM, now that Schimmelfennig's brigade, plus the 1st NY from Kearny's division, and come up to reinforce Krzyżanowski. The fighting in the woods west of Sudley Rd resumed, and came down to a standstill till the 14th GA came in to reinforce the South Carolinians. The Confederates let multiple volleys, sending Krzyżanowski's men running in panic. The Confederates came charging after the disorganized mass of Union troops, clubbing, bayoneting, and knifing resisters, but as soon as they exited the woods into open ground, Union artillery over on Dogan's Ridge fired on them, forcing them to retreat.

To the north, Schimmelfennig's three regiments (61st OH, 74th PA, 8th WV) engaged part of Gregg and Branch's brigades, but were forced to retreat, and Kearny did not move forward. His three brigades marched instead to the banks of Bull Run Creek, where Orlando Poe's brigade forded the creek. Poe's arrival started a feeling of panic at Jackson's HQ, as it looked like the Union troops were getting to the Confederate rear. Jackson ordered his wagons evacuated from the area, and Major John Pelham's horse artillery wheeled into position. The horse artillery and several companies of the 1st VA cavalry engaged in a firefight with Poe's brigade for several minutes. The Union side didn't realize they were getting in the rear of the Confederate lines, and the sight of Confederate infantry in the distance discouraged Poe from advancing any further, and he pulled back across the creek. Robinson's brigade remained in position along the creekbank while Birney's seven regiments scattered. One supported the corps artillery on Matthews Hihll, another was held in reserve, sitting idle, and the remaining three accompanied Poe to the banks of the creek, till the Confederate artillery fire became too much for them, and pulled south into the woods where they joined the Union skirmishing with A.P. Hill's troops.

Sigel was satisfied with the progress of the battle, assuming he was just there to hold until Pope arrived. He was reinforced at 1 PM by Maj Gen Joseph Hooker (III Corps) and the brigade of Brig. Gen. Isaac Stevens (IX Corps). When Pope arrived on the battlefield, Sigel ceded command to him; Pope had expected to see the culmination of his victory, but instead found Sigel's attack had failed completely, and Schurz and Milroy's troops shot up, disorganized, and incapable of further action. Reynolds's and Schneck's divisions were fresh, but committed to guarding the left flank of the Union army. The Union did alos have Heintzelman's corps, and two divisions of Reno available, giving the Union 8 fresh brigades, but Pope was also assuming McDowell would be on the field, and McClellan would also arrive with the II and VI Corps from DC. There were no signs of these troops anywhere. He considered withdrawing briefly to Centreville, but worried about the political fallout if he were seen as insufficiently aggressive. A messanger arrived at this time, giving Pope a note announcing McDowell's corps was close and would soon be on the field. With this, Pope decided to drive in at Jackson's center. What he didn't know yet was Longstreet's first units were in position to Jackson's right, and Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood's division straddled the turnpike, and loosely connected with Jackson's right flank. To the right of Hood, the divisions of Brig. Gens. James Kemper and David "Neighbor" Jones were available, and Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox's division arrived last, and was placed in reserve.

Stuart's cavalry encountered Porter, Hatch, and McDowell moving up the Manassas-Gainesville Road, and halted the Union column in a brief firefight. At that point, a courier arrived with a message for Porter and McDowell, the "Joint Order," which described a move "toward" Gainesville "as soon as communication is established [with the other divisions] the whole command shall halt. It may be necessary to fall back behind Bull Run to Centreville tonight," and nowhere in that order did Pope explicitly direct Porter and McDowell to attack, concluding with, "If any considerable advantages are to be gained from departing from this order it will not be strictly carried out." The last statement made the entire document essentially useless as a military order to the two.

Stuart's cavalry under Col Thomas Rosser deceived the Union generals by dragging tree branches behind a regiment of horses, simulating great clouds of dust from large columns of marching soldiers. At the same time, McDowell got a report from Brig. Gen. John Buford, his cavalry commander, who reported 17 regiments of infantry, a battery, and 500 cavalry were moving through Gainesville at 8:15 AM, which was Longstreet's wing arriving. So again the Union advance halted. Unexplainedly, McDowell didn't forward Buford's report to Pope till 7 PM, so he was operating under two big misconceptions: Longstreet was not near the battlefield, and Porter and McDowell were Marching to attack Jackson's right flank.

As Longstreet's men were placed in their final positions, General Lee ordered an offensive against the Union's left flank. (Longstreet later remembered that Lee "was inclined to engage as soon as practicable, but did not order.") Longstreet saw the divisions of Reynolds and Schenck extended south of the Warrenton Turnpike, overlapping half his line, and argued against attacking at that time. Lee eventually relented when J.E.B. Stuart reported the forces (Porter, McDowell) on the Gainesville-Manassas Road was formidable.

General Pope, assuming the attack on Jackson's right would proceed as he believed he had ordered, authorized four separate attacks against Jackson's front with the intend of diverging the Confederates' attention till Porter arrived and delivered the fatal blow. Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover's brigade attacked at 3 PM, expecting to be supported by Kearny's division. Grover moved his brigade into the woods, with Isaac Stevens's division as support, and charged right at Ed Thomas's GA brigade. Grover's men got to the railroad embankment, and unleashed a volley at near point-blank range on Thomas's regiments, followed by a bayonet charge. Surprised, the Georgians fell back and the fight became hand-to-hand; the South Carolinians under Gregg came to reinforce them, followed by Dorsey Pender's brigade of North Carolinians. Pender his Grover's brigade in the flank, sending the men fleeing in panic with over 350 casualties. Pender's brigade surged out of the woods in pursuit of Grover, but the Union artillery again forced the Confederates to retreat.

To the north, Joseph Carr's brigade had engaged in a low-level firefight with Confederate troops, but Isaac Trimble luckily escaped harm, and began to route the Union troops, driving Nagle back with the help of Henry Forno's LA brigade, and joined by Bradley Johnson and Col Leroy Stafford's 9th LA. To the south, John Hood's division just arrived on the field, forcing Milroy and Nagle back further, helping Trimble's forces. Milroy's brigade, already exhausted, fell apart and ran from the Confederate onslaught. To try to counter the Confederates, Pope pulled Schneck from the south of the turnpike, and with Union artillery support, forced the Confederates back to the railroad embankment; all the while, Kearny was out of the action.

Union troops under Reynolds were ordered to conduct a spoiling attack south of the turnpike, encountering Longstreet's men, causing him to call off his demonstration. Pope dismissed Reynold's concerns, insisting Reynolds had run into Porter's V Corps preparing to attack Jackson's flank. Jesse Reno ordered a IX Corps brigade under Col James Nagle to attack Jackson's center again. This time, Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble's brigade was driven back but restored the line quickly at the embankment, and pursued Nagle's troops into the open fields until Union artillery halted their advances.

Finally, at 4:30 PM, Pope gave an explicit order to attack to Porter, but his aide (his nephew) lost his way and didn't manage to deliver the message till 6:30 PM. In anticipation of the attack that would not be coming to his aid, Pope ordered Kearny to attack Jackson's far left flank, attempting to put strong pressure on both ends of the line. At 5 PM, Kearny sent the brigades of Robinson and Birney to attack A.P. Hill's exhausted division. The brunt of the attack came at Gregg's brigade, which had already defended against two major assaults over eight hours that day, and was almost out of ammo, and had lost several of its officers. As they began to fall back, Gregg chopped some wildflowers with his Revolutionary War scimitar and told them, "Let us die here my men, let us die here." A.P. Hill sent word to Jackson for help, with both Gregg's and Thomas's brigades getting ready to disintegrate.

At the same time, Daniel Leasure's Union brigade of Isaac Stevens's division crept around south and forced back James Archer's TN brigade. Jubal Early's brigade and Lawrence O'Bryan Branch's brigade counterattacked and drove back Kearny's division. During the fighting, Charles Field got a shot near his arm, giving him a laceration, but he held on and continued commanding his troops.

On the Confederates' right, Longstreet observed a movement of McDowell's forces away from his front; the I Corps was moving divisions to Henry House Hill to support Reynolds; this caused Lee to revive his plan for an offensive in that sector, but Longstreet again argued against it, due to inadequate time before dusk. He suggested to recon in force, feel out the position of the enemy, and set up for a morning attack. Lee agreed, and sent Hood's division forward.

On the Union side, McDowell arrived at Pope's HQ, with Pope urging him to move King's division forward. McDowell told him King fell ill and gave command to Brig Gen John Hatch in his stead, whom Pope had taken a dislike to early on in the campaign. Pope ordered Hatch to go up Sudley Road to attack, but Hatch protested that it was clogged with Kearny's troops, and it was not possible to clear them out before dark. Exasperated, Pope repeated his order to advance on the Confederate right, but was distracted by actions on either side of the line. Hood's division had arrived on the left of Jackson, and McDowell then ordered Hatch to reinforce Reynolds despite Hatch's protests that two of his three brigades were exhausted from the fight on the previous day. So, Hatch deployed Doubleday's brigade to the front, but Hood's division forced Hatch and Reynolds back to a position on Bald Hill, overrunning Chinn Ridge in the process. As night fell, Hood pulled back from his exposed position. Again Longstreet and his subordinates argued to Lee they should not be attacking a force they considered to be in a strong defensive position, and for a third time, Lee cancelled a planned assault.

On the Union side, Hood's withdrawal from Chinn Ridge only reinforced Pope's belief that the enemy was retreating. Pope learned from McDowell about Buford's report, and he finally acknowledged that Longstreet was on the field, but he optimistically assumed Longstreet was only there to reinforce Jackson while they withdrew; Hood's division had just done that. Pope gave explicit orders for Porter's corps to rejoin the main body of the army and he planned for another offensive on the 30th.

That evening, Pope wired Halleck with his report of the fighting, describing it as 'severe' and estimating his losses at 7500-8500 men. He estimated the Confederates had lost twice as many, an incorrect assumption since Jackson was fighting a mostly defensive battle. Confederate casualties were lower, though their officer losses had been a little high. Luckily, Trimble, Field, and Forno escaped being wounded. The Union lost five brigade commanders in comparison.

August 30

The last piece of Longstreet's command, Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson's division, marched 17 miles and arrived at 3 AM on the battlefield. They halted on a ridge east of Groveton, exhausted and unfamiliar with the area. At dawn, they realized they were in an isolated position and fell back. Pope's belief that the Confederates were in retreat was reinforced by this movement, which came after the withdrawal of Hood's troops the night before.

This in mind, Pope directed McDowell to move his entire corps up the Sudley Road, and hit the Confederate right flank; McDowell protested, saying he had no idea what was happening on the Confederate left, and would much prefer his troops on Chinn Ridge. He believed it made more sense to attack the right with Heintzelman's troops, which were closer to the area. Pope acquiesced, but detached King's division to support Heintzelman.

At 8AM, Pope had a war council at his HQ, where his subordinates tried to convince him to move cautiously. Union probes of the Confederates at Stony Ridge, around 10 AM indicated Stonewall's men were still firmly entrenched. John Reynolds spoke up that the Confederates had good strength south of the turnpike. Fitz John Porter arrived later with similar intelligence reports. However, both Heintzelman and McDowell conducted personal reconnaissance, which somehow failed to find Jackson's defensive line, and Pope decided to make up his mind to attack the retreating Southerners.

While Porter was bringing up his corps, a further mix-up in orders resulted in the loss of two brigades. Abram Sanders Piatt's small brigade, and Charles Griffin's brigade both pulled out of Porter's main column, marched back down to Manassas Junction, and then up to Centreville. Morell, using an outdated set of orders from the day before, assumed Pope was at Centreville and that he was expected to join him there. Piatt eventually realized something was wrong and turned back towards the battlefield, arriving at Henry House Hill about 4 PM. Griffin and his division commander, Maj. Gen. George Morell, stayed at Centreville, despite finding Pope was not there. Eventually, around 4 PM, Griffin began moving his brigade back towards the action, but by this point, Pope's army was in full retreat, and a mass of wagons and stragglers were blocking the roadway, and the bridge over Cub Run was broken, making it impossible for him to move any further west.

Ricketts's Union division approached the Confederate lines, and it became clear the Confederates were still there in force with no signs of retreating. Pope was unnerved, and thought about waiting for McClellan to arrive with II and VI Corps, but worried he would take credit for any victory in the battle, so he decided to attack immediately rather than wait. Shortly after noon, Pope ordered Porter's corps, with Hatch and Reynolds, to advance west along the turnpike. At the same time, Hooker, Kearny, and Ricketts were to advance along the Confederates' right. This coordinated movement could potentially crush the retreating Confederates; but they weren't retreating, and were hoping to be attacked. General Lee was waiting for an opportunity to counterattack with Longstreet's forces. Though he wasn't sure Pope would attack, Lee had positioned 18 artillery pieces under Col. Stephen D. Lee on the high ground northeast of the Brawner Farm, ideally position to bombard the open fields in front of Jackson's position.

Porter's attack, 3 PM

The Union corps under Porter wasn't in a position to pursue west on the turnpike, but was in the woods north of the turnpike near Groveton. IT took about two hours to prepare the assault on Jackson's line, with ten brigades of about 10,000 men, and 28 artillery pieces on Dogan Ridge to support them. On the right, Ricketts's division would support Heintzelmann, while Sigel's corps remained in reserved behind them. Reynolds's division was stationed near Henry House Hill, with King's division on its right. Porter would strike Jackson's left flank with his 1st Division. Since General Morell was AWOL, command of his troops fell to Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield. George Sykes's division of regulars were held in reserve. As noon approached, temperatures on the field approached 90° F.

The Confederates attempted to strike the first blow. Parts of Ewell's and Hill's divisions came charging out of the woods and surprised some of Ricketts's men with a volley or two, but again the Union artillery on Dogan Ridge overwhelmed them and they withdrew back to the line of the unfinished railroad.

The Union forces faced a daunting task. Butterfield's division had to cross 600 yards of open pasture, the final 150 yards of which were steeply uphill, to attack a strong position behind the unfinished railroad. Porter ordered John Hatch's division to support Butterfield's right flank, and Hatch formed his four brigades into a line of battle, with his own brigade commanded by Col Timothy Sullivan since he assumed division command the day before. Hatch's division only had 300 yards to cross, but had to perform a complex right-wheel maneuver under fire, to hit the Confederate position squarely in its front. Stephen Lee's batteries gave them devastating fire, then volley after volley from the infantry in the line. In the confusion, Hatch was knocked off his horse by an artillery shell, and removed from the field unconscious; it is believed he got a concussion there that would affect him at the later Battle of South Mountain.

The Union troops broke the Confederate line, and routed the 48th VA Infantry. The Stonewall Brigade rushed in to restore the line, and took some casualties, but luckily, its commander, Col Baylor, was not among them. Among the most infamous incident of the battle, Confederates in Col Bradley Johnson's and Col. Leroy Stafford's brigades fired so much that they actually ran out of ammo, and resorted to throwing rocks at the 24th NY, prompting some of the surprised New Yorkers to start throwing them back. To support Jackson's exhausted defenses, which were stretched to breaking, Longstreet's artillery added to the barrage against Union reinforcements attempting to move in, cutting them to pieces. Hatch's brigade fell back in confusion, the men running into Patrick's brigade, also causing them to panic. The mob quickly met up with Gibbon's brigade, which was some distance to the rear, while Doubleday's brigade had inexplicably wandered away from the field of action. Meanwhile, Butterfield's division was buckling under heavy Confederate rifle shot and artillery, and was almost disintegrating.

To shore up Butterfield's faltering attack, Porter ordered Lt Col Robert Buchanan's brigade of regulars into action, but Longstreet's attack on the Union left interrupted him. Withdrawal was also a costly operation. Some of the Confederates in Starke's brigade attempted a pursuit, but were beaten back by the Union reserves along Groveton-Sudley Road. Jackson's command was too depleted to counterattack, in men and munitions, allowing Porter to stabilize the situation north of the turnpike. McDowell, being concerned about Porter's situation, ordered Reynolds's division to leave Chinn Ridge and come to his support, leaving only 2200 Union troops south of the turnpike.

Lee and Longstreet agreed the time was right for the assault, and the objective was Henry House Hill, the key terrain in last year's battle, which could dominate the potential Union line of retreat. Longstreet's command was 25,000 men in five divisions stretched about a mile and a half from Brawner Farm to Manassas Gap Railroad; they would be crossing 1.5 to 2 miles of ground with ridges, streams, and heavily wooded areas, making a well-coordinated battle line very difficult to impossible, so he would need to rely on the drive and initiative of his division commanders. Leading the left was John Hood's Texans, supported by Brig Gen Nathan Evans's South Carolinians. On the right, Kemper's and Jones's divisions. Anderson's division was held in reserve. Just before the attack, Lee signaled to Jackson, "General Longstreet is advancing; Look out for and protect his left flank."

Start of Longstreet's attack at 4PM

On the Union side, Porter was realizing was was happening on his left, and told Buchanan to move to that direction to stem the Confederate onslaught, and then sent a messenger to find the other brigade of regulars, under Col Charles Roberts, to get in the action also. Union defenders south of the turnpike consisted only of two brigades, that of Cols. Nathaniel McLean (Sigel's I Corps, Schenck's division), and Gouverneur Warren (Porter's V Corps, Sykes's division). McLean held Chinn Ridge, Warren was near Groveton, about 800 yards west. Hood's men began the assault about 4 PM, immediately overwhelming Warren's two regiments, the 5th NY and 10th NY; with in the first 10 minutes of contact, the 500 men of the 5th NY would suffer 300 casualties, 120 mortally wounded.

Pope was in his HQ while this was happening, behind Dogan Ridge, oblivious to the chaos, focusing instead on a message he just got from Halleck, announcing that the II and VI Corps, plus Brig. Gen. Darious Couch's division of the IV Corps to reinforce him, and McClellan was ordered to stay in DC. That would give Pope 41 brigades, all under his command without any interference from McClellan. Only when Warren collapsed and McLean was being driven from the field did Pope finally realize what was happening.

4:30 PM on August 30

On the Union side, McDowell ordered Ricketts's division to cease its attack on the Confederate left, which had failed to break through, and try to reinforce the Union left. McDowell rode out with Reynolds to supervise the construction of a new defensive line on Chinn Ridge, just as Porter's shattered troops came running out of the woods to the west. Reynolds protested being ordered to Chinn Ridge, arguing his division was needed to prevent a Confederate attack from the woods.

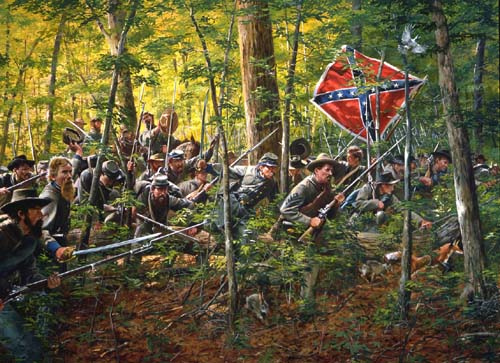

The 5th Texas, fighting at 2nd Manassas, by Don Troiani

McDowell informed Reynolds the Confederates weren't coming from that direction, but from the south and to move his division there immediately. Even before this happened, Union Colonel Martin Hardin (in command of Brig. Gen. Conrad Jackson's brigade), took the initiative himself and marched down to stem the Confederate onslaught. He took Battery G of the 1st PA Artillery, and unleashed a volley of musket fire which stunned the 1st and 4th TX brigades, but the 5th TX to the right kept coming and quickly shot down most of the gunners of Battery G. Nathan Evans's South Carolina Brigade arrived quickly to reinforce the Texans, and got in the rear of Hardin's brigade. Hardin fell wounded and would die of his wounds within two days. Command devolved to Col James Kirk of the 10th PA Reserves. Kirk was shot down within minutes (but would survive, luckily) and Lt Col Leonard took over. The crumbling brigade fell back, with some soldiers pausing to take a few shots at the oncoming Confederates. Nathaniel McLean's brigade of Ohioans arrived on the scene, but was attacked on three sides by Law, Wilcox, and Evans brigades, and soon joined the survivors of Hardin's brigade in a disorganized mob on Henry House Hill.

Final Confederate attack, 5 PM

The first two Union brigades which arrived were from Ricketts's division, commanded by Col Fletcher Webster and Brig Gen Zealous Tower. Ricketts had been at the first battle at Bull Run (the Union name for the battle), where he commanded a regular gun battery, and got captured at the fight for Henry Hill. Tower's brigade slammed Wilcox's Alabamians in the flank, sending them reeling, but was immediately confronted with the fresh division of David Jones. Webster lined up his four regiments to face his Confederate attackers, but was struck dead by an artillery shell right there on the field. His men, disheartened by his death, started falling back. Meanwhile, Tower was shot from his horse, and carried off the field, unconscious. He would also succumb to his wounds after the battle.

Robert Schneck then ordered Col. John Koltes's brigade, which was held in reserve during Sigel's attack yesterday and still fresh, into action, along with Krzyzanowski's brigade, which had been heavily involved in the fighting and was tired. Koltes was quickly struck by an artillery shell and killed; command devolved to Col Richard Coulter of the 11th PA, the highest-ranking officer remaining on the field, and a Mexican War veteran. Though both Koltes's and Krzyzanowski's six regiments were able to hold their ground for a little while, they were quickly overwhelmed by the fresher Confederate soldiers in the brigades of Lewis Armistead, Montgomery Corse, and Eppa Hunton, and started falling back in disorder.

In the first two hours of the Confederates' assault, McDowell had built a new line of defense with Reynolds's and Sykes's divisions. Longstreet's final set of fresh troops, Richard Anderson's division, now took the offensive. Forming a line on Henry House Hill, the regulars of Sykes's division, with Meade's and Seymour's brigades, and Piatt's brigade, held off the final Confederate attack long enough to give the rest of the army enough time to withdraw across Bull Run Creek to Centreville.

Stonewall Jackson, under the relatively ambiguous orders from Lee to support General Longstreet, launched an attack north of the turnpike about 6 PM, the soonest he could muster his exhausted forces. His delay greatly reduced the value of his advance. It coincided with Pope's ordered withdrawal of his units north of the turnpike to assist in the defense of Henry House Hill, and the Confederates were able to overrun a number of artillery and infantry units in their assault. By 7 PM, however, Pope had established a strong defensive line on the hill, and by 8 PM, he had ordered a general withdrawal on the turnpike to Centreville. Unlike the chatic retreat of the First Battle of Manassas, this one was quiet and orderly. The Confederates, tired from battle and low on ammunition, did not pursue the enemy. Though General Lee won a significant victory, he didn't destroy Pope's army.

The final significant action of the battle was when Lee ordered J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry to go around the Union flank and cut off their retreat. Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson's cavalry brigade, along with Col Thomas Rosser's 5th VA Cavalry headed for Lewis Ford, a crossing of Bull Run Creek which would enable them to get in the rear of the Union Army. Unfortunately, they found the crossing blocked by Union cavalry under John Buford, and after a short and fierce engagement, Buford's superior numbers easily won out, and the Confederates pulled back. The clash lasted only ten minutes, and Col Thornton Brodhead of the 1st Michigan Cavalry was shot dead, and John Buford was wounded, but the Union army retreat was safe.

The Confederates, due to their lack of both manpower and ammunition, failed to decisively destroy Pope's army.

After the battle one of the generals was quoted as saying:

A splendid army almost demoralized, millions of public property given up or destroyed, thousands of lives of our best men sacrificed for no purpose. I dare not trust myself to speak of this commander [Pope] as I feel and believe. Suffice to say ... that more insolence, superciliousness, ignorance, and pretentiousness were never combined in one man. It can in truth be said of him that he had not a friend in his command from the smallest drummer boy to the highest general officer.

Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams (II Corps division commander)

On September 12, Pope was relieved of command, and his army merged into the Army of the Potomac as it marched into Maryland under McClellan. He would spend the remainder of the war in the Department of the Northwest in Minnesota, dealing with the Dakota War of 1862, which would become the model for how the Union would deal with the Indians after the war. Pope sought scapegoats to blame for his defeat, and Fitz John Porter was court-martialed on November 25th for his actions, found guilty on January 10th of 1863, and dismissed from the Army on January 21st. He would be later exonerated in 1878 and his sentence reversed two years later.

Note: I changed a few things in this battle, and put a little easter egg in there for the Trekkies. You're welcome.

Zealous Tower and Martin Hardin originally survived long after this battle.

Commanders:

Union: John Pope

Confederate: Robert E Lee

Union Units:

Army of Virginia

Army of the Potomac: III Corps, V Corps, VI Corps, IX Corps, Kanawha Division

Confederate Units: Army of Northern Virginia

Strength:

Union: 77,000 (estimate)

-AoV: 51,000

-AotP: 26,000

Confederate: 62,000 (estimate)

Union Casualties

-Killed: 1,953

-Wounded: 8,914

-Captured/Missing: 4,313

Confederate Casualties:

-Killed: 988

-Wounded: 6,108

Preparing to Go North

Before the battles at Harper's Ferry and Sharpsburg, both Jackson and Longstreet advised Lee of avoiding offensive war with the Yankees, with Longstreet saying, "General, I wish we could stand still and let the damned Yankees come to us!" Lee refused the proposals of assuming a defensive posture, let the Yankees attack, then when they're retreating, attack them. Lee also ignored their advice to ignore the Union garrisons of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg, as capturing them would be a serious diversion of strength, and they had no intentions of holding the towns, so nothing would prevent their reoccupation after they went north. Had Lee remained near Frederick, MD, Harper's Ferry wouldn't have been an issue; but Lee ordered, and to Jackson and Longstreet, that was it. They obeyed and did their best.

Lee wanted to invade the North. To get Davis's approval, he had to use a little deceit, by saying he wanted to place a Confederate army in the North and then offer the Northern people peace.

"Such a proposition," he wrote to President Davis, "coming from us at this time, could in no way be regarded as suing for peace; but being made when it is in our power to inflict injury upon our adversary, would show conclusively to the world that our sole object is the establishment of our independence and the attainment of an honorable peace. The rejection of this offer would prove to the country that the responsibility for the continuance of the war does not rest upon us but that the party in power in the United States elect to prosecute it for purposes of their own. The proposal of peace would enable the people of the United States to determine at their coming elections whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination, which can but be productive of good to both parties without affecting the honor of either."

His benign and peaceable argument played into Davis's prejudices in conducting the war; Jackson wanted to hit northern rail, business, factories, and farms, which Davis didn't want.

Lost and Found

Before leaving and splitting his army, an Ensign noticed some cigars and the Order 191 sitting at a tree, and grabbed it, not wanting to risk the Yankees or his superiors noticing someone had forgotten them. General D.H. Hill got the orders, and thanked the young officer.

Battle of Harper's Ferry (September 12)

View attachment 423767

Jackson's return to Harper's Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia)

After Second Manassas, Lee determined to advance into northern territory, as Jackson had been urging for some time now. His Army of Northern Virginia advanced down the Shenandoah Valley, planning to capture the garrison at Harpers Ferry to secure his supply line back to Virginia. Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Maj. Gen. George McClellan's Army of the Potomac, which outnumbered him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army and senidng one portion to converge and to attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. Col Dixon Miles, the Union commander there, insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town, rather than taking up defensive and commanding positions on the surrounding heights. The slim defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, first encountered the approaching Confederates on the 12th of September, but it was only a brief skirmish. Strong attacks by the Confederates the next day drove the Union troops from the heights.

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived, and were astonished to see the critical positions west and south of town weren't defended. Jackson methodically placed his artillery around Harpers Ferry, and ordered Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah River, in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left in the morning.

By morning on the 15th, Jackson had placed nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and the base of Loudoun Heights. He began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides, and ordered an infantry assault. Miles realized the situation was hopeless, and agreed with his subordinates to raise the white flag to surrender. He was able to surrender personally to the Confederates later that day. After processing more than 12,000 Union prisoners, Jackson's men rushed to Sharpsburg, MD, to rejoin Lee in preparation for the coming battle at Antietam.

Commanders:

Union: Dixon Miles, Julius White

Confederate: Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, A.P. Hill

Strength:

Union: 14,000

Confederate: 21,000

Union Casualties:

-Killed: 43

-Wounded: 173

-Captured: 12,420

Confederate Casualties:

-Killed: 37

-Wounded: 233

Maryland Campaign

While at Frederick, McClellan got word on the 13th that the Confederates were at Martinsburg and Harper's Ferry and began marching slowly towards Sharpsburg to try to cross the river and meet them.

Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) (September 17)

Luckily for General Lee, A.P. Hill had finished processing and paroling the prisoners from Harper's Ferry, and carried off large supplies overnight, and was available with his 1900 troops for action near Sharpsburg.

Near the town of Sharpsburg, General Lee deployed his available troops behind the Antietam Creek, along a low ridge, starting on the 15th of September. While it was an effective defensive position, it was not an impregnable one. To his detriment, neither he nor General Jackson effectively conducted reconnaissance on the field, which was a hindrance to their performance at this position. The terrain provided excellent cover for infantrymen, with rail and stone fences, outcroppings of limestone, and little hollows and swales. The creek in front was only a minor barrier, ranging from 60 to 100 feet in width, and fordable in places, and having 3 stone bridges a mile apart each. The Confederates were blocked to the rear by the Potomac.

By the time McClellan arrived, Lee had around 38,000 men available to him, less than half the size of the Federal army, but McClellan believed them to be up to 100,000 men and he delayed for a day. This gave the Confederates time to prepare their defensive positions, and to let all of Longstreet and Jackson's men to rest from their march, and A.P. Hill's division to arrive.

Had McClellan attacked on the 15th or 16th he might've won on numbers, but he delayed till the 17th. McClellan ordered Hooker's I Corps to cross the creek and probe enemy positions. Meade's division cautiously attacked Hood's troops near the East Woods; unfortunately this skirmish in the East Woods just served to signal McClellan's intentions to Lee, who prepared his defenses accordingly.

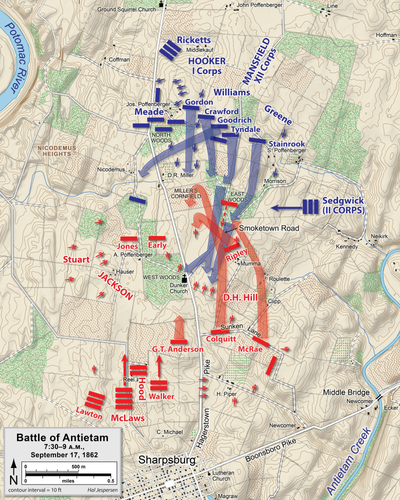

McClellan's battle plans were ill-coordinated and poorly executed; each of his subordinates had only the orders for his own corps, and no general orders describing the entire battle plan. The battlefield terrain made it difficult for the various commanders to monitor events outside their own sectors, and McClellan's HQ was over a mile away at Philip Pry House, east of the creek, making it difficult for him to control the separate corps. The overall effect was that the battle progressed the 17th as three separate, mostly uncoordinated battles; morning in the north, midday in the middle, and afternoon in the south. The lack of coordination practically nullified the nearly two-to-one advantage in manpower the Union enjoyed (72,000 to 38,000), and allowed Lee to shift his defensive forces for each offensive.

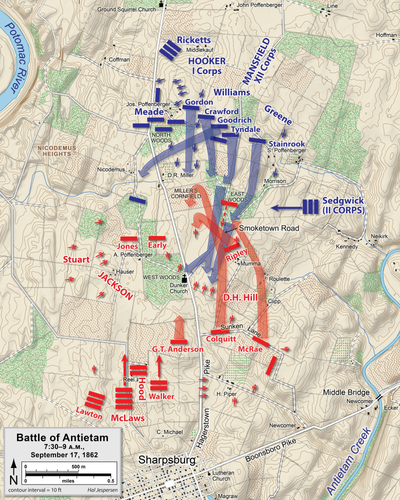

Morning in the Cornfield (North)

The battle started at dawn (about 5:30 AM), with an attack down the Hagerstown Turnpike by the Union I Corps under Joseph Hooker. He had about 8600 men, just a little more than the 7700 under Stonewall Jackson. Abner Doubleday's division moved to Hooker's right, James Ricketts's moved to the left, and George Meade's PA Reserves deployed to the center/rear.

The fighting started with an artillery duel, Confederates under J.E.B. Stuart and Col. Stephen D Lee west and east. Union fire returned from nine batteries on the ridge behind the North Woods and twenty 20-lb Parrott rifles, 2 miles east of the creek. This caused heavy casualties.

Hooker's infantry met the Confederates concealed in the cornfield, and were shot down, but began returning fire; having not seen them first was deadly to the Union effort. Soon the battle turned to a melee, rifles becoming hot and fouled from too much firing.

Through the East Woods, Meade's 1st Brigade of Pennsylvanians under command of Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour began advancing, and exchanged fire with Col. James Walker's brigade of Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia Troops. Walkers men forced Seymour's back, aided by the artillery fire from Lee; Rickett's division entered the Cornfield and was also torn up by Confederate artillery. Seymour would die from his wounds the next day. Brig. Gen. Abram Duryée's brigade marched into the volleys of Col. Marcellus Douglass's Georgia brigade, directly, and endured heavy fire from 250 yards. They gained no advantage because of the lack of reinforcements, so Duryée ordered a withdrawal.

The reinforcements that Duryée had expected, namely brigades under the commands of Brig. Gen. George L Hartsuff and Col. William Christian, had difficulties reaching the battle. Hartsuff had been wounded by a shell, and Christian dismounted and fled to the rear in terror. when the men were finally rallied and advanced into the Cornfield, they met the same artillery and infantry fire as those before them. Despite superior Union numbers, the Louisiana "Tiger" Brigade, including members of the Creole and free black communities, under Harry Hays, entered the fray and forced the Union troops back to the East Woods. The 12th MA Infantry's casualties were 67%, the highest of any unit that day. But, the Louisiana Tigers were beaten back eventually when the Union troops brought up a battery of 3" ordinance rifles, and rolled them directly into the Cornfield, point-blank fire at the Tigers, slaughtering them; they lost 287 of 500 men.

The Cornfield remained a bloody stalemate, but Union advances a few hundred yards west were more successful. Brig. Gen. John Gibbon's 4th Brigade of Doubleday's division (now the Iron Brigade)began advancing down and astride the turnpike, into the cornfield, and in the West Woods, pushing Jackson's men aside. They were halted by a 1150-man charge from Starke's brigade, leveling heavy fire on the Union troops from 30 yards away. The Confederate brigade withdrew after getting heavy return fire from the Iron Brigade; luckily Starke himself was not wounded. At the same time, the Union advance on Dunker Church resumed and cut a large gap in Jackson's defensive line, which was on the verge of collapse. Though at a steep cost, Hooker's corps was making progress.

Confederates got reinforcements just after 7 AM, with A.P. Hill, McLaws, and Richard H Anderson having arrived from Harpers Ferry. Around 7:15 Lee moved Anderson's Georgia birgade from the right flank to aid Jackson. At 7 AM, Hood's division of 2300 men advanced through the West Woods and pushed the Union troops back through the Cornfield again. The Texans were particularly fierce in their fighting since they were called from their reserve position, interrupting the first hot breakfast they had had in days. They were aided by three brigades of D.H. Hill's division coming in from Mumma Farm, southeast of the Cornfield, and Jubal Early's brigade, coming in from the West Woods from the Nicodemus Farm, where they had been supporting J.E.B. Stuart's horse artillery. Some Union officers of the Iron Brigade rallied around the artillery of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, with Gibbon himself ensuring they didn't lose a single caisson. Hood's men bore the brunt of the fighting on the Confederate side, and paid the price - 50% casualties - but they did prevent the defensive line from crumbling, and they held off the I Corps.

Hooker's men also paid heavily, but without gaining their objectives. After two hours and 2600 casualties, they were back where they started. The Cornfield, an area of about 250 yards deep, 400 yards wide, was a scene of immense destruction. It has been estimated it changed hands at least 15 times that morning. Hooker called for support from the 7200 men of Mansfield's XII Corps.

Assaults by the XII Corps,

7:30 to 9:00 a.m.

Half of Mansfield's men were raw recruits, and he himself was also inexperienced, having gotten command only two days before. Although he was a 40-year veteran, he had never led a large number of troops in combat. He was concerned his troops would bolt under fire, so he marched them in a formation called "column of companies, closed in mass," which translated to a regiment ten ranks deep, instead of the normal two. It presented an excellent artillery target for the Confederates, and Mansfield himself was shot in the chest and died the next day. Alpheus Williams assumed the command temporarily.

The new recruits of the 1st Division of Mansfield made no progress against Hood's line, reinforced by brigades of D.H. Hill's division under Colquitt and McRae. The 2nd Division of the XII Corps came up against A.P. Hill and McRae's men. The Confederates held Dunker Church, protected by Stephen Lee's batteries.

Hooker attempted to gather the scattering remnants of his I Corps to continue the assault, but a black Confederate sharpshooter spotted the general's conspicuous white horse and shot him through the foot. Command then fell to General Meade, since Hooker's most senior subordinate, James Ricketts, had also fallen wounded. Without Hooker, though, there was no general left with the authority to rally the I and XII Corps. Greene's men also came under heavy fire in the West Woods and withdrew.

The Dunker Church after September 17, 1862. Here, both Union and Confederate dead lie together on the field.

The Dunker Church after September 17, 1862. Here, both Union and Confederate dead lie together on the field.

Trying to turn the Confederate left flank and relieve pressure on Mansfield's men, Sumner's II Corps sent two divisions into battle at 7:20 AM. Sedgwick's 5400-man division was the first to ford the Antietam Creek, and entered the East Woods intending to turn left, and force the Confederates south into the assault of Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps. But the plan went awry.

They got separated from William French's division, and at 9 AM Sumner, who was accompanying the division, launched the attack in an unusual battle formation - three brigades in three long lines, men side-by-side, only 50-70 yards separating the lines. They were assaulted first by Confederate artillery, and then from three sides by divisions of Early, Walker, and McLaws, and in less than half an hour, Sedwick's men were forced to retreat in great disorder back to their starting point with over 2400 casualties, including Sedgwick himself, who was taken out of action for several months by a wound.

The final actions of the morning phase of the Battle of Sharpsburg were about 10 AM, when two regiments of XII Corps advanced, only to be confronted by John Walker's division, newly arrived from the Confederate right. They fought between the Cornfield and West Woods, with the Union troops gaining some ground here when they forced Walker's men back with two brigades of Greene's division.

The morning phase of the battle ended with casualties on both sides of almost 14,000, including four Union corps commanders.

Midday Phase

By midday, the battle had shifted to the center of the Confederates' line. Sumner had accompanied the morning attack of Sedgwick's division, but one of his other divisions under French had lost contact, and inexplicably headed south. French found skirmishers and ordered his men forward; by this time, one of Sumner's aides, his son, located French and relayed the order for him to divert Confederate attention by attacking their center.

French confronted D.H. Hill's division, which had about 2500 men, less than half the number French had, and three of his five brigades had been torn up in the morning combat. This was theoretically the weakest point of Longstreet's line. Fortunately for Hill, his men were in a strong defensive position, on the top of a gradual ridge, in a sunken road, worn down by years of wagon traffic, which formed a natural trench.

French launched a series of brigade-sized assaults against the Confederate improvised breastworks about 9:30 AM. The first brigade, mostly inexperienced troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Max Weber, was quickly cut down by heavy rifle fire; neither side used their artillery. The second Union attack included more raw recruits under Col. Dwight Morris, and faced heavy fire but managed to beat back a counterattack by Robert Rodes's Alabama Brigade. The third Union attack, under the command of Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball, included three veteran regiments, but they too fell to the Confederate fire coming from the sunken road. French's division suffered 1890 casualties out of 5700 in just under an hour of fighting.

Reinforcements arrived on both sides, and by 10:30 AM General Lee sent his final reserve, some 3400 men under Maj Gen Richard Anderson, to bolster Hill's line and extend it to the eright, preparing an attack that would hopefully envelop French's left flank. Unfortunately for him, the 4000 men of Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson's division arrived on French's left; this was the last of Sumner's three divisions, which had been held up in the rear by McClellan as he continued to organize his reserve forces. The Union struck the first blow.

Union Irish Brigade flag, the basis for several flags of a similar design.

Leading off the fourth attack of the day against the sunken road was the Irish Brigade, of Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher. As they advanced with their emerald green flags, snapping in the breeze, a regimental chaplain, Father William Corby, rode back and forth across the front of the formation shouting words of conditional absolution prescribed by the Roman Catholic Church for those who were about to die. The mostly Irish immigrants lost 541 men to heavy volleys before they were ordered to withdraw.

Gen. Richardson personally dispatched the brigade of Brig. Gen. John Caldwell into battle about noon, after being told that Caldwell was in the rear, behind a haystack, and finally the tide turned. Anderson's Confederate division had been little help to the defenders after Gen. Anderson was wounded early in the fighting (he would recover). Luckily for the Confederates, George B Anderson, Col. Charles Tew (2nd NC), and Col. John Gordon (6th AL) remained alive and helped stem the Union advance from going too far.

Afternoon Phase

By the afternoon, the action had moved to the southern end of the battlefield. Longstreet was arrayed on both sides of Boonsboro Rd, his artillery able to hit across the battlefield, rather than north of Sharpsburg.

McClellan's plan was for Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and the IX Corps to conduct a diversionary attack to support Hooker's I Corps, hoping to draw Confederate attention away from the intended main attack in the north. Unfortunately Burnside was instructed to wait for explicit orders before launching his attack, which didn't reach him till about 10 AM. He was also strangely passive during battle preparations because he was still disgruntled that McClellan had abandoned the previous arrangements of 'wing commanders' reporting to him. Implicitly refusing to give up his higher authority, he was using Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox of the Kanawha Division as corps commander, funneling orders to the corps through him. Overall, Burnside had four divisions (12,500 troops) and 50 guns east of Antietam Creek.

Facing Burnside were the Confederates which had been depleted by Lee's movement of units to bolster their left flank. Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs had two artillery batteries, but Longstreet's shifting helped somewhat. Toombs had 400 men, the 2nd and 20th GA regiments, and there were four thin brigades guarding the ridges near Sharpsburg. They were defending Rohrbach's Bridge, a three-span 125-foot stone structure at the southmost crossing of Antietam. The bridge would become infamous as Burnside's Bridge because of the coming battle. It was a difficult objective; the road leading to it ran parallel to the creek, and was exposed to enemy fire. It was dominated by a 100-foot high wooded bluff on the west bank, strewn with boulders from an old quarry, making infantry and sharpshooter fire from good covered positions a dangerous impediment to crossing.

In this sector the creek was rarely more than 50 feet wide, and several stretches were only waist deep, and out of Confederate range. Burnside ignored this fact during the battle, and concentrated his plan instead of storming the bridge, while simultaneously crossing a ford McClellan's engineers had identified half a mile downstream. When his men reached it, they found the banks too high to negotiate. While Col George Crook's Ohio brigade prepared to attack the bridge with support from Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis's division, the rest of the Kanawha Division and Brig. Gen. Isaac Rodman's division struggled through thick brush trying to locate Snavely's Ford, 2 miles downstream, intending to flank the Confederates, but failing due to their struggles.

Crook's assault on the bridge was led by skirmishers from the 11th Connecticut, who were ordered to clear the bridge for the Ohioans to cross to assault the bluff. After taking punishing fire for 15 minutes, the Connecticut men withdrew with 145 casualties, about 1/3 their strength, including the commander, Col Henry Kingsbury, who was fatally wounded. Crook's main assault went awry when his unfamiliarity with the terrain caused his men to reach the creek a quarter mile upstream from the bridge, where they exchanged volleys with Confederate skirmishers for the next few hours.

While Rodman's division was out of touch, slogging towards Snavely's Ford, Burnside and Cox directed a second assault at the bridge by one of Sturgis's Brigades, led by the 2nd MD and 6th NH. They also fell prey to the Confederate sharpshooters and artillery, and their attack fell apart. It was about noon, and McClellan was losing patience. He sent a succession of couriers to motivate Burnside to move forward. He ordered one aide, "Tell him if it costs 10,000 men he must go now." He increased pressure by sending his inspector general, Col. Delos Sackett, to confront Burnside, who was indignant, saying, "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders."

The third Union attempt to take the bridge was at 12:30 PM by Sturgis's other brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero. It was led by the 51st NY and 51st PA who with adequate artillery support and a promise that a recently canceled whiskey ration would be restored if they were successful, charged downhill and took up positions on the east bank. Maneuvering a captured light howitzer into position, they fired double canister down the bridge and got within 25 yards of their enemy. By 1 PM, Confederate ammunition was running low, and word reached Toombs that Rodman's men were crossing Snavely's Ford on their flank. He ordered a withdrawal. His Georgians cost the Union over 500 casualties while taking less than 140 themselves, and had stalled Burnside's assault on the southern flank for over 3 hours.

Burnside's assault against stalled on its own. His officers had neglected to transport ammunition across the bridge, which itself was becoming a bottleneck for soldiers, weapons, and artillery. This made another two-hour delay. General Lee used this time to bolster his right flank, bringing A.P. Hill's light division out of its rest, and they made it to the right of D.R. Jones's force with rested troops.

Burnside was not prepared for Hill's return to combat, and his plan was to move around a weakened Confederate right flank, converge on Sharpsburg, and cut off Lee's army from Boteler's Ford, their only escape round across the Potomac. At 3 PM, Burnside left Sturgis's division in reserve on the west bank, and moved west with over 8,000 troops, most fresh, and 18 guns for close support.

The initial assault led by the 79th NY "Cameron Highlanders" failed against Jones's division, having been reinforced by A.P. Hill. To the left, Rodman's division advanced towards Harpers Ferry Road, its lead brigade under Col. Harrison Fairchild, containing several colorful Zouaves of the 9th NY, commanded by Col. Rush Hawkins. They came under heavy shellfire from over a dozen enemy guns mounted on a ridge to their front, but kept pushing forward. There was a panic in the streets of Sharpsburg, clogged with retreating Confederates. Of the five brigades in Jones's division, only Toombs's brigade was still intact, but had only 700 men.