Of Hannibal’s Carthage, Part 8:

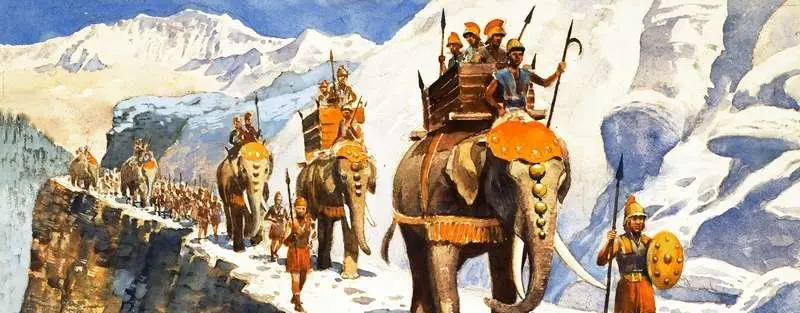

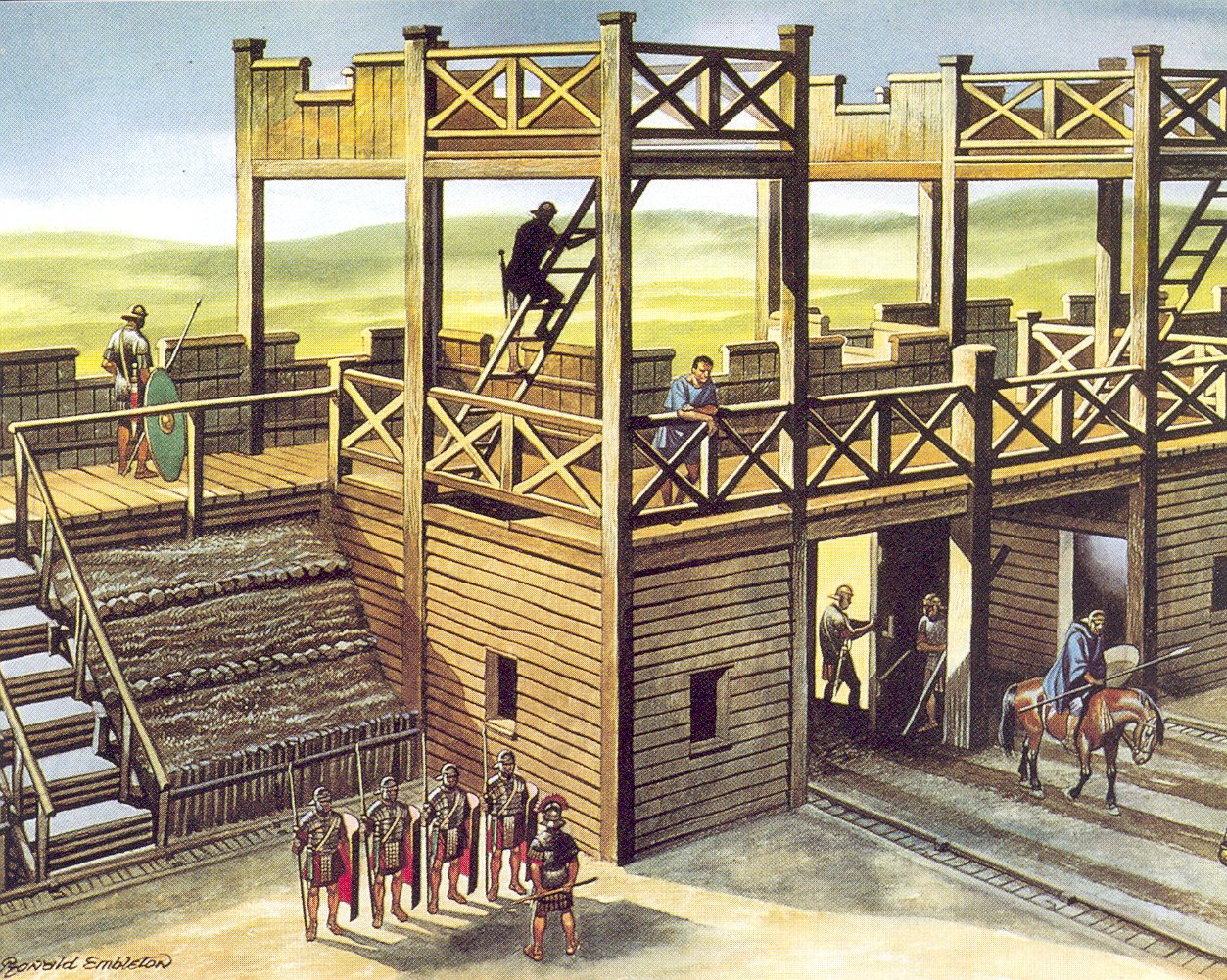

Invented by the Greek engineer Polyidus of Thessaly, the Helepolis or 'city-taker' was the biggest siege engine ever constructed. King Demetrius I of Macedon commissioned the architect Epimachus of Athens to build the biggest recorded Helepolis, which he used in the failed siege of Rhodes in 305 BC. This huge construction was said to be nearly forty meters tall, split into nine storeys, with catapults at its base and two stairways giving access to its multiple levels. Built entirely of wood, it was covered with iron plates to protect it from fire. During the siege the Rhodians managed to dislodge some of these plates, prompting Demetrius to withdraw the weapon for fear of its destruction. Hannibal himself hired Greek engineers for his Second Roman War and later the Third Roman War. When on campaign, the armies of the ancient world expected to live off the land by purchasing food and pillaging enemy territory. This made them especially vulnerable to scorched earth tactics, where defenders would purposely destroy crops to starve invaders. While naval vessels were able to deliver supplies, their use limited armies to coastal expeditions and it was not until the development of new, land-based supply methods that warfare changed significantly. These methods increased the efficiency and self-sufficiency of armies and provided a significant advantage over enemies, as evidenced by the success of the reformed Carthaginian Armies. The military reforms of Hannibal in Carthage in the Second Roman War marked a significant change in pay for Carthaginian soldiers. Falcatesair did now consider the new annual salary of 100 denarii, complimented by payment in land or cash up to 2,000 denarii, suitable payment for 24 years hard service. Hannibal was quick to identify the role that the dissatisfied troops had played in the years of strife. He set up the Military Treasury, a pot of money initiated by his own funds and topped up by regular citizen tax payments; it provided soldiers with a pension equivalent to 16 years' pay.

The science of measurement, metrology, was invented by the Egyptians during the Bronze Age. Its creation was inspired by a lust for money as Pharaoh Sesostris wanted to measure and tax his subjects' arable land. Units of measurement were typically based on parts of the human body or a man’s capacity: the digit, palm, foot and pace for example. Not surprisingly there were many local variations, but as trade between cities and states increased there were attempts to introduce standard quantities of everything. The Greek king Pheidon is widely recognized as the creator of the first set of agreed common weights and measures. Hannibal did the same for Carthage and provided a fixed system that would benefit the trade in his whole Republic and their trade partners. Throughout the ancient period there was a drive to find new exploitable land, either through clearing forests or, more frequently, draining lakes, marshes and flooded plains. The Greeks set their sights on draining Lake Copais, a swampland north of Athens that was flooding fertile land around it as the natural flow of water was blocked due to regular earthquakes. In 325BC an engineer, Crates, sought to solve the problem by supplementing the natural drainage in the area with a long tunnel. The work was halted by the military ambitions of Alexander the Great but resumed centuries later. In 1890 the lake was finally drained and the area is now used for farming. Hannibal's had similar goals in Libya as he cultivated and watered more and more land for use by the new colonists. Additional there was a simple principle of seed selection, sowing the best quality seeds provided the best quality crop. The strength of a crop was affected by the seed from which it was grown and through seed selection a farmer could develop a crop free of disease that offered a more profitable yield. The farmer had to take the time to select only seeds from the most healthy and strong plants in a crop, removing the small, withered, discolored or inferior seeds. Selecting the seed was usually simple: the best seed was the heaviest, and would therefore be found settled on the very bottom of the grain on the threshing floor.

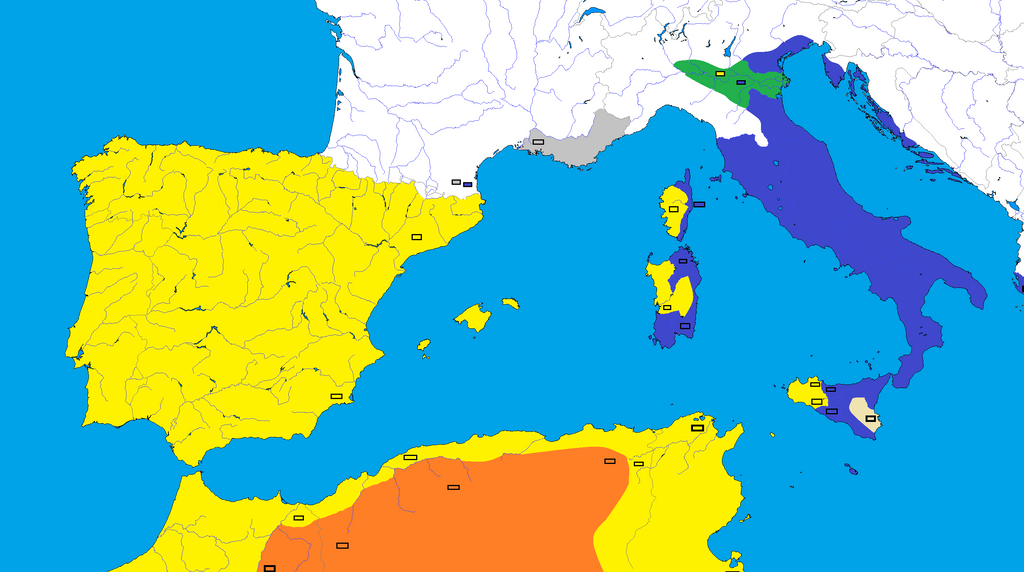

There is some debate as to the exact origins of the first coins, although it is widely accepted that some of the Mediterranean’s earliest coinage came from Lydia in Asia Minor. The first Greek coinage was produced on the island of Aegina, some 24 km south of Athens. Aegina was a trading nation that minted a coin known as the 'turtle', named for the sea-turtle design punched into it. Pebble-like in appearance, these early coins were made from electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. The Barcas family of Hannibal under their separate Empire of Nova Carthago had begun to make their own coinage and Hannibal later did so too for all of Carthage. In 420BC the Greeks made their first attempt to introduce a standardised currency. The Carthaginians under Hannibal soon realized the need for a system of fixed coinage and minted their coins to be worth the weight of their gold and silver 'bullion' content. This, unfortunately, lent itself to a gradual debasement as the more corrupt states began to mint their own - alloying the metals in the coins to maintain weight while using the spare gold and silver to make more debased ones. As ever-increasing populations demanded more goods it became necessary to explore the principles of mass-production. This led to the development of piecework: the construction of component parts that could be produced quickly and in large quantities. Teams of workers would then assemble these parts into goods. Punic philosopher and writer, Melkharbal the Elder, tells of shops dedicated to the production of individual chandelier parts. There is also evidence to suggest that factory-like production was used in urban areas for the manufacture of pots, building parts and military items like near the harbor of Carthage.

The Romans inherited their knowledge of brickmaking from the Etruscans. Distrustful of a foreign technique, early Roman fired bricks were made from roof tiles which had already proved durable. By the Republican era fired bricks were widely used due to the perfection of a baking process whereby the mortar was absorbed. Roman bricks were standardized and came in four sizes, ranging from the 'bassalis' which was eight Roman inches square or around twenty centimeters, right up to the 'bipedailis' which was two Roman feet square, around sixty centimeters. Brickmakers often stamped their wares with their names and dated them by adding the names of the Consuls in office at the time. After his Second Roman War in Italy, Hannibal adapted the Etruscn technique and traded bricks and technologies with them for his own building projects. Hannibal also imported modern sewers as an engineering achievement more stupendous than any. The system grew into a complex network of sewers that expanded with the cities of Carthage and collected the excrement to later use them as fertilizer.

During the Second and Third Roman War, Hannibal introduced radical reforms which changed how the Carthaginian army was recruited and structured, and therefore how it fought in battle. Regular soldiers instead of Mercenaries were trained. The Falcaten (Carthaginian Legion) organization was scrapped with the group becoming the basic unit. Hannibal also reformed the weaponry and fighting methods of the Carthaginian army. Not every man was equipped identically, but the most common used types of weapons and armor became standardized and groups with such units were educated in Punic commands. Many groups from areas all over the Carthaginian territories in one army did not understand each others tongue, but they had learned basic Punic and followed their Carthaginian Commanders loyal. Traditionally, the citizen armies of the ancient world were supplied by a combination of mercenaries, levies and volunteer troops. Often farmers and landowners, these men ultimately looked to return to their plots and families, comforted by the spoils of war. The professional solider was a different beast entirely. He gave his life to the army, never wavering to think on what awaited him back home. However, when a state discharged these men without suitable reward, they often turned to their generals. If successful in finding the spoils to offer his men, a general could exert huge influence and power. Hannibal used such troops in the last years of his life in exile away from Carthage, but this tactics and army type traveled back to Carthage with his body after his death, well preserved in his written texts about state and military art.

Wooden ships routinely sprang leaks and the accumulation of water within a large hull had to be bailed out by hand, a slow and sometimes dangerous task. It was a job made easier by the invention of the screwpump. The Greek inventor,Archimedes of Syracuse invented the Archimedean screw or screwpump. With this device bigger and better trade ans warships would be build in the Greek states and Carthage. All states built their navies to safeguard their merchants' vital trade across the Mediterranean. The Carthaginians were the most daring seafarers of the ancient world, preferring to hire mercenaries for their land wars whilst concentrating on the construction of a huge fleet of ever-larger ships. As Carthaginian trade and the need to transport troops increased, so did the importance of sea control. They built vast war galleys manned by citizen rowers. Alongside Greek-style triremes, quinqueremes ('fives') and septiremes ('sevens'), reinforced for ramming, were constructed. Even so, the largest ship of the ancient world was the Syracusia, designed by Archimedes and built in 240 BC by King Hiero II. It used some sixty times the resources needed for an average trireme and took 300 skilled workmen over a year to build. The palace ship later used to travel the body of the dead Hannibal from Quart Hnba'albrq (Quart Hannibal Barkas) back to Carthage had a similar design.

Invented by the Greek engineer Polyidus of Thessaly, the Helepolis or 'city-taker' was the biggest siege engine ever constructed. King Demetrius I of Macedon commissioned the architect Epimachus of Athens to build the biggest recorded Helepolis, which he used in the failed siege of Rhodes in 305 BC. This huge construction was said to be nearly forty meters tall, split into nine storeys, with catapults at its base and two stairways giving access to its multiple levels. Built entirely of wood, it was covered with iron plates to protect it from fire. During the siege the Rhodians managed to dislodge some of these plates, prompting Demetrius to withdraw the weapon for fear of its destruction. Hannibal himself hired Greek engineers for his Second Roman War and later the Third Roman War. When on campaign, the armies of the ancient world expected to live off the land by purchasing food and pillaging enemy territory. This made them especially vulnerable to scorched earth tactics, where defenders would purposely destroy crops to starve invaders. While naval vessels were able to deliver supplies, their use limited armies to coastal expeditions and it was not until the development of new, land-based supply methods that warfare changed significantly. These methods increased the efficiency and self-sufficiency of armies and provided a significant advantage over enemies, as evidenced by the success of the reformed Carthaginian Armies. The military reforms of Hannibal in Carthage in the Second Roman War marked a significant change in pay for Carthaginian soldiers. Falcatesair did now consider the new annual salary of 100 denarii, complimented by payment in land or cash up to 2,000 denarii, suitable payment for 24 years hard service. Hannibal was quick to identify the role that the dissatisfied troops had played in the years of strife. He set up the Military Treasury, a pot of money initiated by his own funds and topped up by regular citizen tax payments; it provided soldiers with a pension equivalent to 16 years' pay.

The science of measurement, metrology, was invented by the Egyptians during the Bronze Age. Its creation was inspired by a lust for money as Pharaoh Sesostris wanted to measure and tax his subjects' arable land. Units of measurement were typically based on parts of the human body or a man’s capacity: the digit, palm, foot and pace for example. Not surprisingly there were many local variations, but as trade between cities and states increased there were attempts to introduce standard quantities of everything. The Greek king Pheidon is widely recognized as the creator of the first set of agreed common weights and measures. Hannibal did the same for Carthage and provided a fixed system that would benefit the trade in his whole Republic and their trade partners. Throughout the ancient period there was a drive to find new exploitable land, either through clearing forests or, more frequently, draining lakes, marshes and flooded plains. The Greeks set their sights on draining Lake Copais, a swampland north of Athens that was flooding fertile land around it as the natural flow of water was blocked due to regular earthquakes. In 325BC an engineer, Crates, sought to solve the problem by supplementing the natural drainage in the area with a long tunnel. The work was halted by the military ambitions of Alexander the Great but resumed centuries later. In 1890 the lake was finally drained and the area is now used for farming. Hannibal's had similar goals in Libya as he cultivated and watered more and more land for use by the new colonists. Additional there was a simple principle of seed selection, sowing the best quality seeds provided the best quality crop. The strength of a crop was affected by the seed from which it was grown and through seed selection a farmer could develop a crop free of disease that offered a more profitable yield. The farmer had to take the time to select only seeds from the most healthy and strong plants in a crop, removing the small, withered, discolored or inferior seeds. Selecting the seed was usually simple: the best seed was the heaviest, and would therefore be found settled on the very bottom of the grain on the threshing floor.

There is some debate as to the exact origins of the first coins, although it is widely accepted that some of the Mediterranean’s earliest coinage came from Lydia in Asia Minor. The first Greek coinage was produced on the island of Aegina, some 24 km south of Athens. Aegina was a trading nation that minted a coin known as the 'turtle', named for the sea-turtle design punched into it. Pebble-like in appearance, these early coins were made from electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. The Barcas family of Hannibal under their separate Empire of Nova Carthago had begun to make their own coinage and Hannibal later did so too for all of Carthage. In 420BC the Greeks made their first attempt to introduce a standardised currency. The Carthaginians under Hannibal soon realized the need for a system of fixed coinage and minted their coins to be worth the weight of their gold and silver 'bullion' content. This, unfortunately, lent itself to a gradual debasement as the more corrupt states began to mint their own - alloying the metals in the coins to maintain weight while using the spare gold and silver to make more debased ones. As ever-increasing populations demanded more goods it became necessary to explore the principles of mass-production. This led to the development of piecework: the construction of component parts that could be produced quickly and in large quantities. Teams of workers would then assemble these parts into goods. Punic philosopher and writer, Melkharbal the Elder, tells of shops dedicated to the production of individual chandelier parts. There is also evidence to suggest that factory-like production was used in urban areas for the manufacture of pots, building parts and military items like near the harbor of Carthage.

The Romans inherited their knowledge of brickmaking from the Etruscans. Distrustful of a foreign technique, early Roman fired bricks were made from roof tiles which had already proved durable. By the Republican era fired bricks were widely used due to the perfection of a baking process whereby the mortar was absorbed. Roman bricks were standardized and came in four sizes, ranging from the 'bassalis' which was eight Roman inches square or around twenty centimeters, right up to the 'bipedailis' which was two Roman feet square, around sixty centimeters. Brickmakers often stamped their wares with their names and dated them by adding the names of the Consuls in office at the time. After his Second Roman War in Italy, Hannibal adapted the Etruscn technique and traded bricks and technologies with them for his own building projects. Hannibal also imported modern sewers as an engineering achievement more stupendous than any. The system grew into a complex network of sewers that expanded with the cities of Carthage and collected the excrement to later use them as fertilizer.

During the Second and Third Roman War, Hannibal introduced radical reforms which changed how the Carthaginian army was recruited and structured, and therefore how it fought in battle. Regular soldiers instead of Mercenaries were trained. The Falcaten (Carthaginian Legion) organization was scrapped with the group becoming the basic unit. Hannibal also reformed the weaponry and fighting methods of the Carthaginian army. Not every man was equipped identically, but the most common used types of weapons and armor became standardized and groups with such units were educated in Punic commands. Many groups from areas all over the Carthaginian territories in one army did not understand each others tongue, but they had learned basic Punic and followed their Carthaginian Commanders loyal. Traditionally, the citizen armies of the ancient world were supplied by a combination of mercenaries, levies and volunteer troops. Often farmers and landowners, these men ultimately looked to return to their plots and families, comforted by the spoils of war. The professional solider was a different beast entirely. He gave his life to the army, never wavering to think on what awaited him back home. However, when a state discharged these men without suitable reward, they often turned to their generals. If successful in finding the spoils to offer his men, a general could exert huge influence and power. Hannibal used such troops in the last years of his life in exile away from Carthage, but this tactics and army type traveled back to Carthage with his body after his death, well preserved in his written texts about state and military art.

Wooden ships routinely sprang leaks and the accumulation of water within a large hull had to be bailed out by hand, a slow and sometimes dangerous task. It was a job made easier by the invention of the screwpump. The Greek inventor,Archimedes of Syracuse invented the Archimedean screw or screwpump. With this device bigger and better trade ans warships would be build in the Greek states and Carthage. All states built their navies to safeguard their merchants' vital trade across the Mediterranean. The Carthaginians were the most daring seafarers of the ancient world, preferring to hire mercenaries for their land wars whilst concentrating on the construction of a huge fleet of ever-larger ships. As Carthaginian trade and the need to transport troops increased, so did the importance of sea control. They built vast war galleys manned by citizen rowers. Alongside Greek-style triremes, quinqueremes ('fives') and septiremes ('sevens'), reinforced for ramming, were constructed. Even so, the largest ship of the ancient world was the Syracusia, designed by Archimedes and built in 240 BC by King Hiero II. It used some sixty times the resources needed for an average trireme and took 300 skilled workmen over a year to build. The palace ship later used to travel the body of the dead Hannibal from Quart Hnba'albrq (Quart Hannibal Barkas) back to Carthage had a similar design.

Last edited:

:origin()/pre00/9689/th/pre/i/2017/064/6/f/siege_of_akragas__agrigentum___by_sheldonoswaldlee-db19crk.png)