Chapter 142: Second Battle of Herdonia

Chapter 142: Second Battle of Herdonia

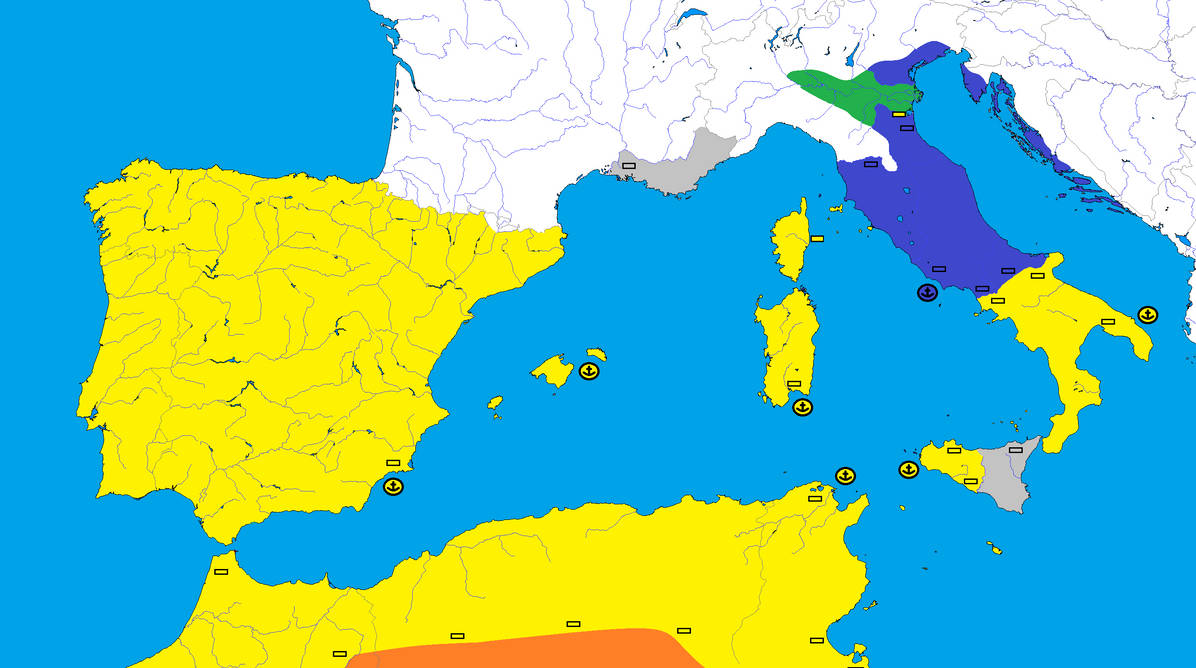

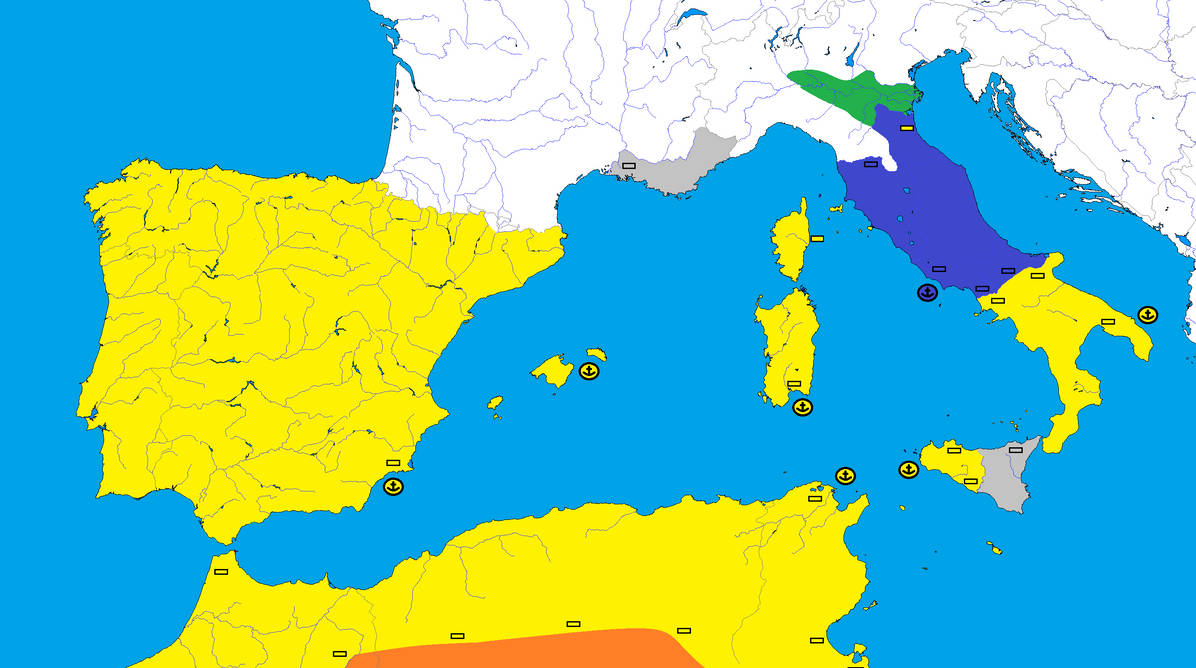

The Second Battle of Herdonia was actually a battle nearby Herdonia when the Roman Forces intruding into Apulia meat with the Carthagoan cavalry and infantry heading north to stop them, supported by a group of local Apulian, Calabrian and Samnitian forces, mainly militia joining them. They meat with Roman Legionaries, at first only cavalry scouting then infantry as well in the Second Battle that took place outside Herdona in the farmlands and hedges nearby the city. This made movement for the original cavalry engagement hard and the infantry had it even harder, as half the time they were unable to directly see the enemy and how he moved. Therefore the Second Battle of Herdonia was a confusing mess and the Punic general actually lead his forces from the top of one of four elephants participating in the battle to have a better overview, while also staying closer to the forces themselves, unlike the Roman commander who watched from afar atop of a nearby hill, so that his orders took some time to reach his Legionaries. Still many infantry forces were limited in their sight and even the cavalry had problems with their movements in this maze of farmland and hedges. This confusion not only slowed down the battle, but actually lead to some confusion overall were some smaller groups of both sides ended up completely surrounded by the enemy. The strangest thing was that some of these forces managed to get back to their own lines in all of the confusion, sometimes even without actually clashing and fighting enemy forces at all. The Punic forces then retreated the best they could as they started to lose coordination and overview of the battle themselves and started to burn down the estates and farms belonging to Roman senators and noble families while leaving alone those that belonged to the locals and Punic allies alike. This lead to the Roman commander fearing the Punic forces and their allies might burn down most of Herdona and the surrounding farmlands in a scorched earth tactics, so he pushed after them, right into the burning hedges, farms and town itself. By doing so he left his overview position and leading to even further confusion of the Roman forces near Herdona. Once the Punic commander saw this move, he let his forces turn around and surround the Roman Legionaries who had now a confused forward march trough smoke and hedges.

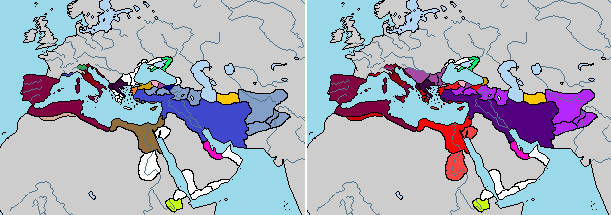

Unlike they had formerly believed however, the Punic forces had not retreated so they could take out the fire, but actually moved around, allowing the Punic soldiers and allied militia to surprisingly turn around them and actually flank the Roman sides. The Roman legionaries were stunned and completely surprised by this unexpected move and together with the partly still burning hedges and farms around them, they soon routed, turning into a full routing that became a complete chaos were several Roman Legionaries would be overrun and stepped to death while trying to escape, while a few others burned in the fire. The Second Battle of Herdona thereby was a completely disaster for the inexperienced Roman Commander, loosing 16,000 of 18,000 total Roman forces, but helped the Romans to keep the siege of Brundisium going for longer, as well as helping them deal with the Punic Army of Hasdrubal Barca coming from the North with Gallic mercenaries. Their goal was to catch and fight his Punic army before they would be able to unite with those in the South of Italy. To delay the Siege of Brundisium or maybe even relief the city, so that Hannibal was forced to let a army stay in the south to deal with it, leaving him less forces to unite his armies with Hasdrubal and march into Rome itself. Hannibal knew this danger as well and marched with his northern army between Capua and Sarguntum in hope of tricking the Romans into believing that they marched onto Rome or at least could put it in direct danger, thereby forcing the Roman Legions here to remain in Central Italy, instead of heading north and combining forces to crush Hasdrubal's army heading down south towards them. This still meant that Hasdrubal's forces needed to engage and defeat at least one Roman army himself, but Hannibal believed that he would be up for such a task, otherwise the Punic position in Italy would be compromised and in need of further reinforcements from Hesperia and Libya.

The Second Battle of Herdonia was actually a battle nearby Herdonia when the Roman Forces intruding into Apulia meat with the Carthagoan cavalry and infantry heading north to stop them, supported by a group of local Apulian, Calabrian and Samnitian forces, mainly militia joining them. They meat with Roman Legionaries, at first only cavalry scouting then infantry as well in the Second Battle that took place outside Herdona in the farmlands and hedges nearby the city. This made movement for the original cavalry engagement hard and the infantry had it even harder, as half the time they were unable to directly see the enemy and how he moved. Therefore the Second Battle of Herdonia was a confusing mess and the Punic general actually lead his forces from the top of one of four elephants participating in the battle to have a better overview, while also staying closer to the forces themselves, unlike the Roman commander who watched from afar atop of a nearby hill, so that his orders took some time to reach his Legionaries. Still many infantry forces were limited in their sight and even the cavalry had problems with their movements in this maze of farmland and hedges. This confusion not only slowed down the battle, but actually lead to some confusion overall were some smaller groups of both sides ended up completely surrounded by the enemy. The strangest thing was that some of these forces managed to get back to their own lines in all of the confusion, sometimes even without actually clashing and fighting enemy forces at all. The Punic forces then retreated the best they could as they started to lose coordination and overview of the battle themselves and started to burn down the estates and farms belonging to Roman senators and noble families while leaving alone those that belonged to the locals and Punic allies alike. This lead to the Roman commander fearing the Punic forces and their allies might burn down most of Herdona and the surrounding farmlands in a scorched earth tactics, so he pushed after them, right into the burning hedges, farms and town itself. By doing so he left his overview position and leading to even further confusion of the Roman forces near Herdona. Once the Punic commander saw this move, he let his forces turn around and surround the Roman Legionaries who had now a confused forward march trough smoke and hedges.

Unlike they had formerly believed however, the Punic forces had not retreated so they could take out the fire, but actually moved around, allowing the Punic soldiers and allied militia to surprisingly turn around them and actually flank the Roman sides. The Roman legionaries were stunned and completely surprised by this unexpected move and together with the partly still burning hedges and farms around them, they soon routed, turning into a full routing that became a complete chaos were several Roman Legionaries would be overrun and stepped to death while trying to escape, while a few others burned in the fire. The Second Battle of Herdona thereby was a completely disaster for the inexperienced Roman Commander, loosing 16,000 of 18,000 total Roman forces, but helped the Romans to keep the siege of Brundisium going for longer, as well as helping them deal with the Punic Army of Hasdrubal Barca coming from the North with Gallic mercenaries. Their goal was to catch and fight his Punic army before they would be able to unite with those in the South of Italy. To delay the Siege of Brundisium or maybe even relief the city, so that Hannibal was forced to let a army stay in the south to deal with it, leaving him less forces to unite his armies with Hasdrubal and march into Rome itself. Hannibal knew this danger as well and marched with his northern army between Capua and Sarguntum in hope of tricking the Romans into believing that they marched onto Rome or at least could put it in direct danger, thereby forcing the Roman Legions here to remain in Central Italy, instead of heading north and combining forces to crush Hasdrubal's army heading down south towards them. This still meant that Hasdrubal's forces needed to engage and defeat at least one Roman army himself, but Hannibal believed that he would be up for such a task, otherwise the Punic position in Italy would be compromised and in need of further reinforcements from Hesperia and Libya.