Chapter 39: Corsica and Sardinia:

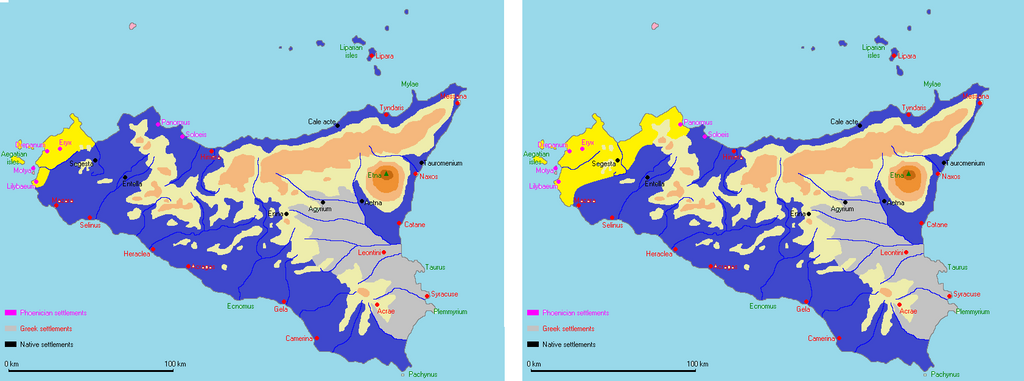

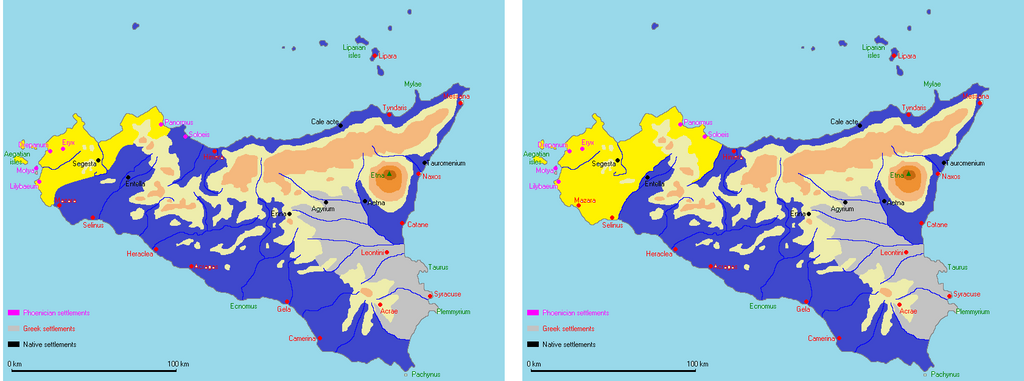

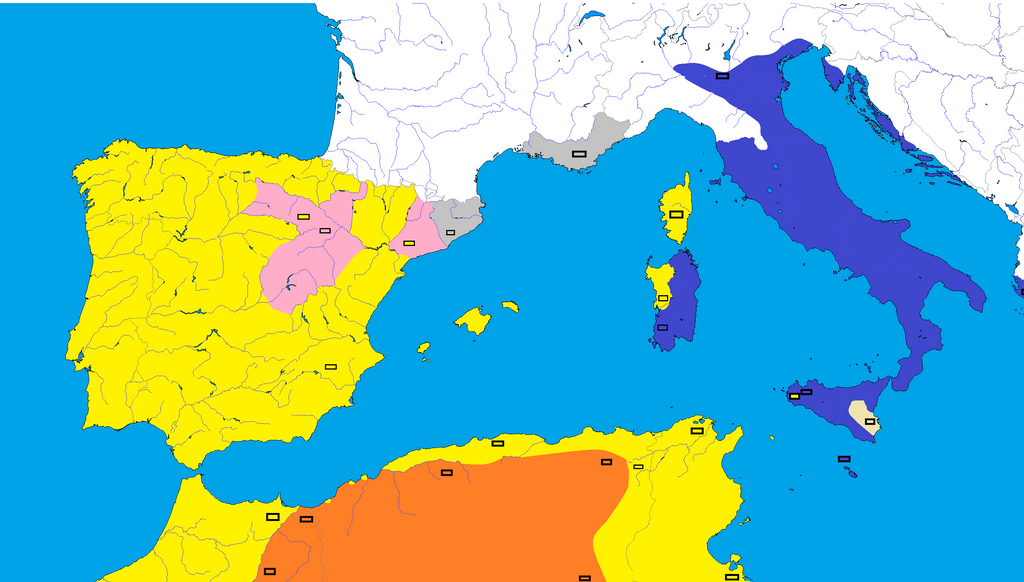

It was said that the Phoenicians (Libyans) first colonized Corsica, but that the Greeks had a brief foothold in Corsica with the foundation of Aleria in 566 BC. They were expelled by an alliance of the Etruscans and the Carthaginians. For a few centuries Carthage dominated the island until it was lost to the Roman Republic after the Mercenary War. While the Phoenicians establish several commercial stations in Corsica and Sardinia, the Greeks arrived after them and build own colonies. The Carthaginian colony with the help of the Etruscans, conquered the Greek colony of Alalia, on Corsica in 535 BC. After Corsica, even Sardinia came under control of the Carthaginians. With the loss of the Mercenary War the Carthaginians lost Corsica and Sardinia right after they had already lost Sicily to the Romans. Corsica and Sardinia soon became a roman province but were far from being controlled properly. While the Romans settled in both Islands on the coast, the interior areas remained under the control of the native population. Revolts occurred but as the interior area was densely forested, the Romans avoided fighting there and set these territories aside as the land of the barbarians. Some even called the annexation of both Islands a mistake, since they were viewed as backward and unhealthy. Corsica was the worst since the Romans did not receive much spoil nor were the prisoners willing to bow to foreign rule, and to learn anything Roman. They soon became known as bestial people resorting to live by plunder, said that “whoever has bought one (Corsican), aggravating their purchasers by their apathy and insensibility, regrets the waste of his money”. Many Romans agreed that the same goes for the Sardinians, who acquired an infamous reputation for being untrustworthy and killing their master if they had a chance. Since the Sardinian captives were flooding the Roman slave market after one of the Roman victories over a serious outbreak from the mountain tribes, the proverb Sardi venales ("Sardinians for cheap") became in fact an everyday Latin expression to indicate anything cheap and worthless. The Romans referred to the Sardinians, as ill-disposed as no other towards the Roman people, as "every one worse than his fellow" (alius alio nequior), even more as their rebels in the highlands, that kept fighting the Romans in guerrilla-style, as "thieves with rough wool cloaks" (latrones mastrucati) The Roman orator linked in fact the Sardinians to the ancient Berber tribes of Libya, a Poenis admixto Afrorum genere Sardi ("from the Punics, mixed with African blood, originated the Sardinians"), Africa ipsa parens illa Sardiniae ("Africa itself is the parent of Sardinia"), using also the name Afer (African) and Sardus (Sardinian) as interchangeable, to prove their supposed cunning and hideous nature inherited by the former Carthaginian masters.

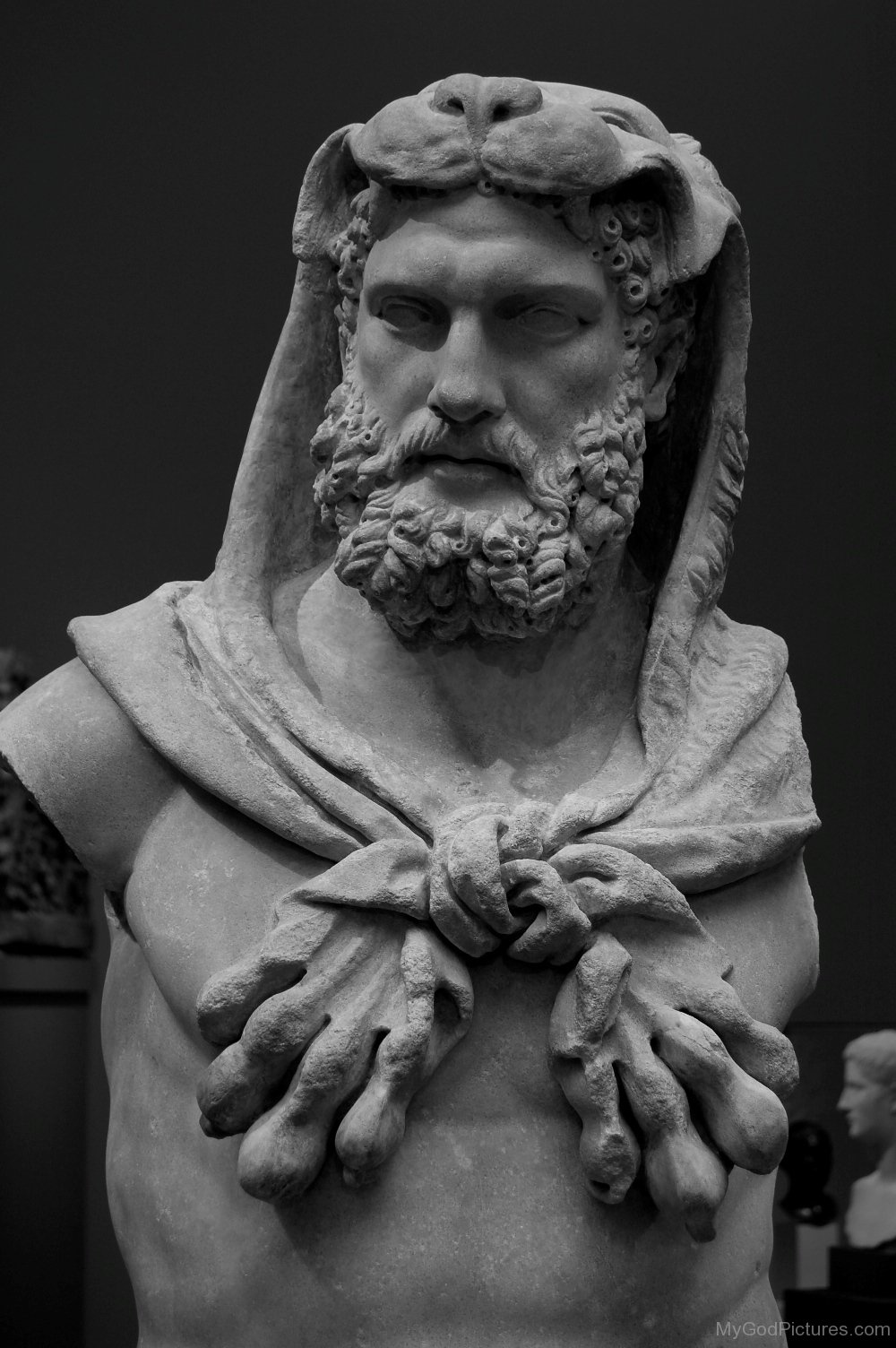

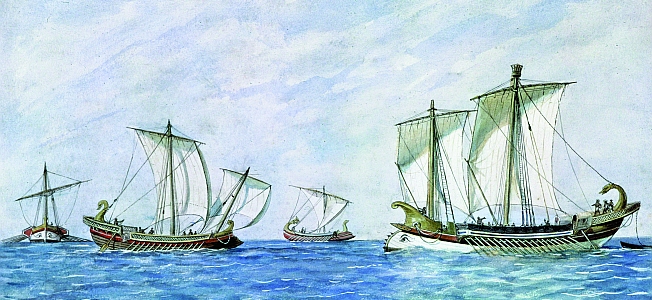

These rebellious behavior was the main reason, the Carthaginians under Hampsicora landed an invasion force with 8.000 infantry and 700 cavalry from the Baleares in Corsica. Hampsicora was one of the richest landowners of Sardinia and directly subject of Carthage, as the Romans attacked and conquered the Island. While the mountainous inland area was still ruled by the native Nuragic populations, which, although become tolerant of the Carthaginians after many hostilities, were obviously hostile to the Roman conquest. Hampsicora who had lost land and wealth to roman landowners saw his opportunity to retake Corsica for Carthage in the Second Roman War and was more than willing to attack the Romans together with a native revolt and incoming Carthaginian fleets and armies. Hampsicora and Hanno of Tharros disguised as merchants landed before the main Carthagian invasion forces and animated a revolt of the coastal cities of Sardinia against Roman rule. Many Sardinians, especially the tribe of the Ilienses allied with Carthage. The senators of Cornus of witch Hampsicora was the chief magistrate even allied with Carthage since they had heard from Hannibals stunning victories in Hesperia and rumors spread that a Carthaginian invasion of the island was planned and asked for aid in their cause. The original plan was to land both forces in Sardinia, but Hampsicora who was reuniting with the fleet to lead it directly in the harbor of Cornus for a stunning victory was driven north by the wind and with him the whole Fleet under Mahar (later called the Skilled). Their army of 8.000 infantry and 700 cavalry landed in Corsica, while Hasdrubal the Bald an his army from Libya with 15.000 infantry, 1.500 cavalry and twenty elephants landed in Sardinia just as planned.

Thanks to that Hannibal's original plan to crush the Roman forces with superior numbers in Sardinia and then turn north to liberate Corsica was failed from the beginning. Not willing to give up just jet or to delay the invasion, Hasdrubal the Bald, landed his army in Tharros, since the Roman army from Carales was already marching northwest to fight the rebellious cities. Quintus Mucius Scaevola the Roman consul was gathering his troops in Caralis to face the enemy and started to march on the western cities before the Carthaginians would arrive. He had one and a half Legions at his disposal, 7,500 Legionaries and 450 cavalry as well as the same number of allied troops. Since he told the senate in Rome of the revolting cities and that he assumed an Carthaginian invasion could occur any moment there were hot tempered debates weather or not the reserve armies should be sent to Sardinia immediately instead of invading Hesperia and helping Messilia again. After all Titus got his wish, two other roman armies should immediately send to Sardinia to reinforce his position and to fight the rebels, but a Carthaginian navy prevented these supplies from landing at the island an forced them back to Italy.

Josto, son of Hampsicora ready to welcome Hasdrubal in Cornus was eager to fight the Romans without waiting for his fathers return or for the second Carthaginian army. Corno itself had just a few troops, but Josto assuring that he knew the Roman commander and the terrain of Sardinia itself convinced Hasdrubal to battle the Romans outside of the city. Quintus Mucius Scaevola was fighting the rebels and Carthaginians at the Battle of Othoca, where neither side could win. Thanks to Josto who didn't knew the terrain or the roman commander as good as he thought and was no skilled tactician or strategy the army of Hasdrubal got into a bad position and nearly lost the battle. Thanks to Baal, Hasdrubal the Bald was able to counterattack and even if neither side did win he saved parts of his army and also crippled the roman army badly with heavy losses. With this outcome, the western cities of the Isle remained under Rebel/Carthago rule, while the south and the east remained under Roman domain. Each side was now willing to trade and supply their coastal regions while landing fresh troops to drive the enemy of the island.

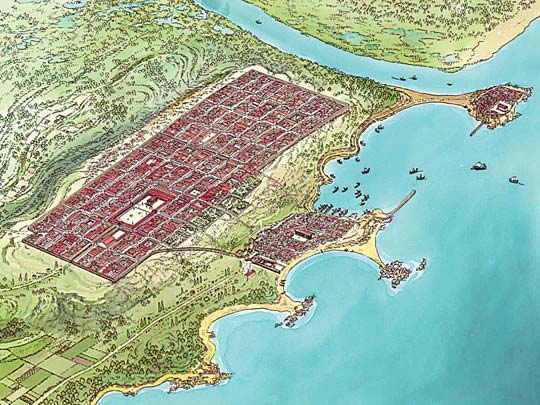

Hampsicora himself immediately recognized that he was driven away from home island and had instead landed in Corsica. Hampsicora knew that they had to sail back to supply Hasdrubals army if they wanted to beat the Romans in Sardinia, but Mahar still commander of the fleet and army refused, as he saw the opportunity to totally destroy the roman position in Corsica together with the native rebellious mountain tribes. By doing so he hoped to force the Romans to send new troops and supplies to retake Corsica so that the Invasion of Sardinia would relieved. The roman troops in Corsica had just 2,500 Legionaries and 200 cavalry that were occupied with securing the town of Aleria/Alalia from raids of the mountain barbarians. Mahar send negotiators to these tribes and promised them that under new carthaginian rule they could live by their own rules and rites as promised by Shophet Hannibal while profiting from trade with Carthage and their goods. Mahar's plan nearly was failing as one of the mountain tribes tried to attack him, but failed in his ambush. Mahar managed to beat them, sold them into slavery via Aiacium to Carthaginian traders and impressed the other tribes by doing so without many own losses. Now was his greatest hour, as Mahar married a local queen/ or princess, allied himself with all the other tribes that were fighting the Romans and marched over the mountain road from Alacium to Aleria. The romans were outnumbered by this Carthaginian/Corsican army and forced to evacuate the city -army and roman settlers and traders alike- if they wished to survive the fall of Corsica. Mahar was now called Mahar the Skilled and resided in the freshly conquered city of Aleria, where he and his Corsican allies plundered the Roman treasures, goods and weapon depots and split them fair. To Romans and Carthaginians alike Mahar would later be known as the man that united the Punics and Corses as a unified tribe on Corsica and as the first fair and just ruler of the whole Island in it's history. Corsica under Mahar would later become part of an autonomous confederate province within the administration of the Isles in the Mediterranean between Italy and Africa.

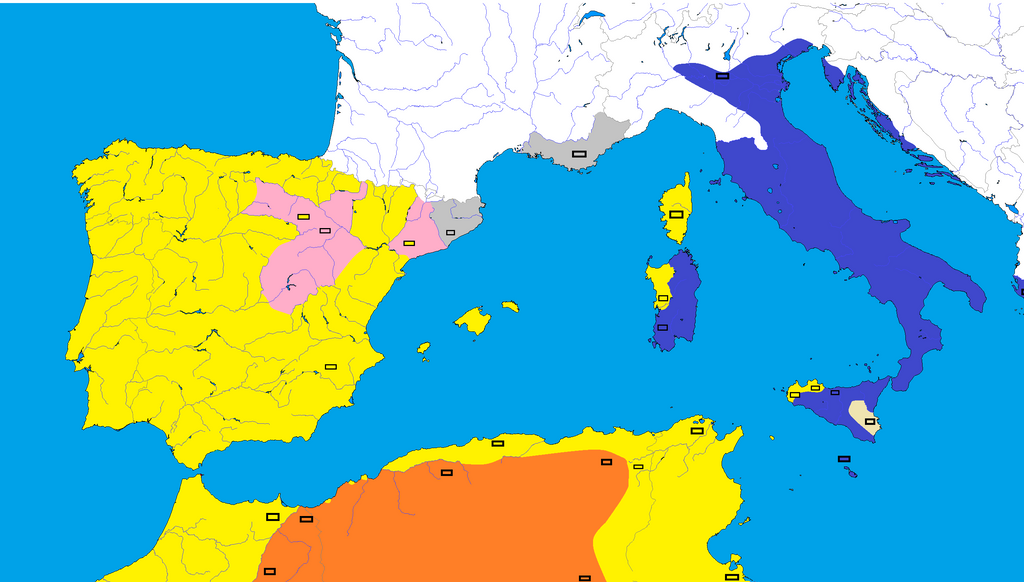

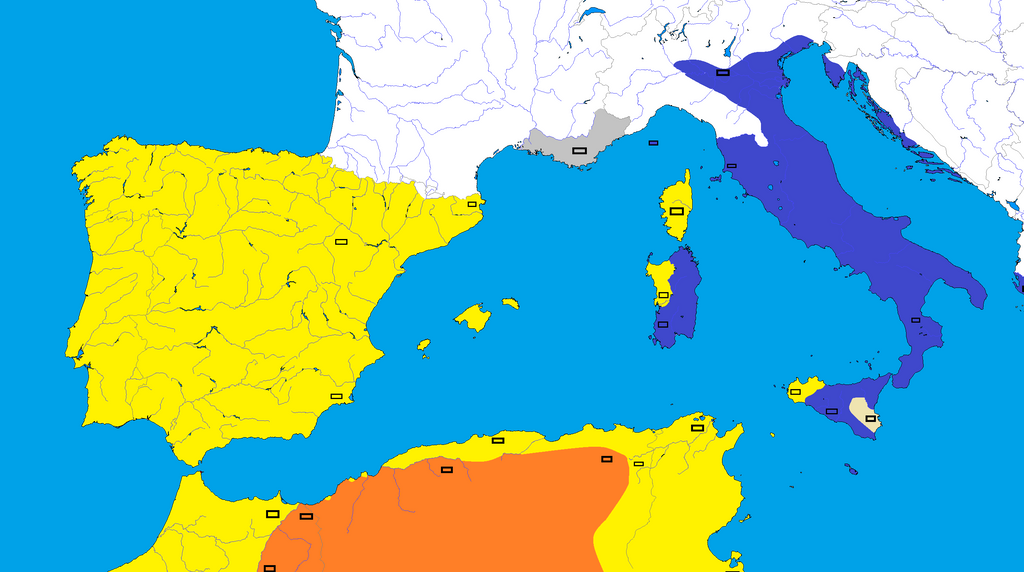

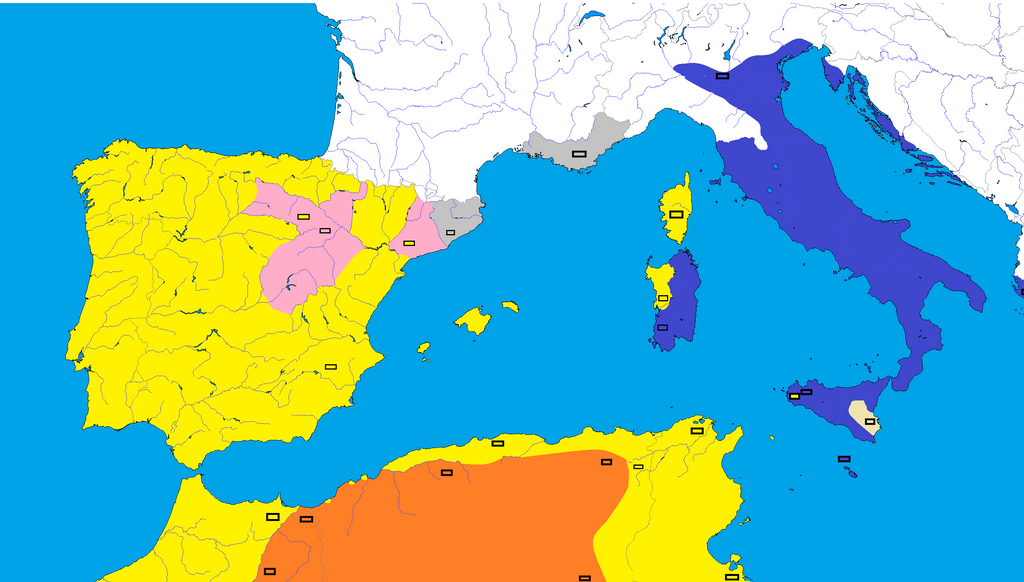

(current world map)

It was said that the Phoenicians (Libyans) first colonized Corsica, but that the Greeks had a brief foothold in Corsica with the foundation of Aleria in 566 BC. They were expelled by an alliance of the Etruscans and the Carthaginians. For a few centuries Carthage dominated the island until it was lost to the Roman Republic after the Mercenary War. While the Phoenicians establish several commercial stations in Corsica and Sardinia, the Greeks arrived after them and build own colonies. The Carthaginian colony with the help of the Etruscans, conquered the Greek colony of Alalia, on Corsica in 535 BC. After Corsica, even Sardinia came under control of the Carthaginians. With the loss of the Mercenary War the Carthaginians lost Corsica and Sardinia right after they had already lost Sicily to the Romans. Corsica and Sardinia soon became a roman province but were far from being controlled properly. While the Romans settled in both Islands on the coast, the interior areas remained under the control of the native population. Revolts occurred but as the interior area was densely forested, the Romans avoided fighting there and set these territories aside as the land of the barbarians. Some even called the annexation of both Islands a mistake, since they were viewed as backward and unhealthy. Corsica was the worst since the Romans did not receive much spoil nor were the prisoners willing to bow to foreign rule, and to learn anything Roman. They soon became known as bestial people resorting to live by plunder, said that “whoever has bought one (Corsican), aggravating their purchasers by their apathy and insensibility, regrets the waste of his money”. Many Romans agreed that the same goes for the Sardinians, who acquired an infamous reputation for being untrustworthy and killing their master if they had a chance. Since the Sardinian captives were flooding the Roman slave market after one of the Roman victories over a serious outbreak from the mountain tribes, the proverb Sardi venales ("Sardinians for cheap") became in fact an everyday Latin expression to indicate anything cheap and worthless. The Romans referred to the Sardinians, as ill-disposed as no other towards the Roman people, as "every one worse than his fellow" (alius alio nequior), even more as their rebels in the highlands, that kept fighting the Romans in guerrilla-style, as "thieves with rough wool cloaks" (latrones mastrucati) The Roman orator linked in fact the Sardinians to the ancient Berber tribes of Libya, a Poenis admixto Afrorum genere Sardi ("from the Punics, mixed with African blood, originated the Sardinians"), Africa ipsa parens illa Sardiniae ("Africa itself is the parent of Sardinia"), using also the name Afer (African) and Sardus (Sardinian) as interchangeable, to prove their supposed cunning and hideous nature inherited by the former Carthaginian masters.

These rebellious behavior was the main reason, the Carthaginians under Hampsicora landed an invasion force with 8.000 infantry and 700 cavalry from the Baleares in Corsica. Hampsicora was one of the richest landowners of Sardinia and directly subject of Carthage, as the Romans attacked and conquered the Island. While the mountainous inland area was still ruled by the native Nuragic populations, which, although become tolerant of the Carthaginians after many hostilities, were obviously hostile to the Roman conquest. Hampsicora who had lost land and wealth to roman landowners saw his opportunity to retake Corsica for Carthage in the Second Roman War and was more than willing to attack the Romans together with a native revolt and incoming Carthaginian fleets and armies. Hampsicora and Hanno of Tharros disguised as merchants landed before the main Carthagian invasion forces and animated a revolt of the coastal cities of Sardinia against Roman rule. Many Sardinians, especially the tribe of the Ilienses allied with Carthage. The senators of Cornus of witch Hampsicora was the chief magistrate even allied with Carthage since they had heard from Hannibals stunning victories in Hesperia and rumors spread that a Carthaginian invasion of the island was planned and asked for aid in their cause. The original plan was to land both forces in Sardinia, but Hampsicora who was reuniting with the fleet to lead it directly in the harbor of Cornus for a stunning victory was driven north by the wind and with him the whole Fleet under Mahar (later called the Skilled). Their army of 8.000 infantry and 700 cavalry landed in Corsica, while Hasdrubal the Bald an his army from Libya with 15.000 infantry, 1.500 cavalry and twenty elephants landed in Sardinia just as planned.

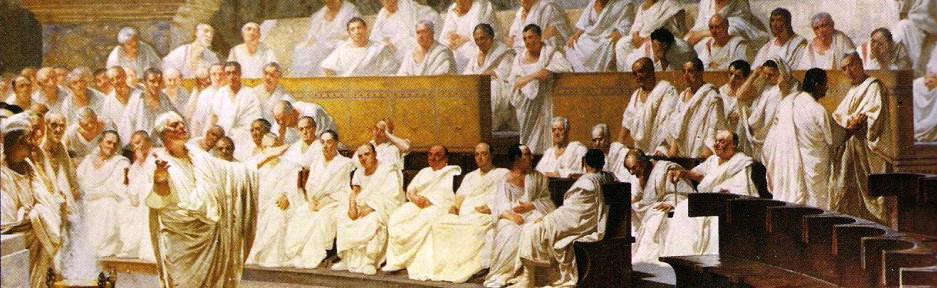

Thanks to that Hannibal's original plan to crush the Roman forces with superior numbers in Sardinia and then turn north to liberate Corsica was failed from the beginning. Not willing to give up just jet or to delay the invasion, Hasdrubal the Bald, landed his army in Tharros, since the Roman army from Carales was already marching northwest to fight the rebellious cities. Quintus Mucius Scaevola the Roman consul was gathering his troops in Caralis to face the enemy and started to march on the western cities before the Carthaginians would arrive. He had one and a half Legions at his disposal, 7,500 Legionaries and 450 cavalry as well as the same number of allied troops. Since he told the senate in Rome of the revolting cities and that he assumed an Carthaginian invasion could occur any moment there were hot tempered debates weather or not the reserve armies should be sent to Sardinia immediately instead of invading Hesperia and helping Messilia again. After all Titus got his wish, two other roman armies should immediately send to Sardinia to reinforce his position and to fight the rebels, but a Carthaginian navy prevented these supplies from landing at the island an forced them back to Italy.

Josto, son of Hampsicora ready to welcome Hasdrubal in Cornus was eager to fight the Romans without waiting for his fathers return or for the second Carthaginian army. Corno itself had just a few troops, but Josto assuring that he knew the Roman commander and the terrain of Sardinia itself convinced Hasdrubal to battle the Romans outside of the city. Quintus Mucius Scaevola was fighting the rebels and Carthaginians at the Battle of Othoca, where neither side could win. Thanks to Josto who didn't knew the terrain or the roman commander as good as he thought and was no skilled tactician or strategy the army of Hasdrubal got into a bad position and nearly lost the battle. Thanks to Baal, Hasdrubal the Bald was able to counterattack and even if neither side did win he saved parts of his army and also crippled the roman army badly with heavy losses. With this outcome, the western cities of the Isle remained under Rebel/Carthago rule, while the south and the east remained under Roman domain. Each side was now willing to trade and supply their coastal regions while landing fresh troops to drive the enemy of the island.

Hampsicora himself immediately recognized that he was driven away from home island and had instead landed in Corsica. Hampsicora knew that they had to sail back to supply Hasdrubals army if they wanted to beat the Romans in Sardinia, but Mahar still commander of the fleet and army refused, as he saw the opportunity to totally destroy the roman position in Corsica together with the native rebellious mountain tribes. By doing so he hoped to force the Romans to send new troops and supplies to retake Corsica so that the Invasion of Sardinia would relieved. The roman troops in Corsica had just 2,500 Legionaries and 200 cavalry that were occupied with securing the town of Aleria/Alalia from raids of the mountain barbarians. Mahar send negotiators to these tribes and promised them that under new carthaginian rule they could live by their own rules and rites as promised by Shophet Hannibal while profiting from trade with Carthage and their goods. Mahar's plan nearly was failing as one of the mountain tribes tried to attack him, but failed in his ambush. Mahar managed to beat them, sold them into slavery via Aiacium to Carthaginian traders and impressed the other tribes by doing so without many own losses. Now was his greatest hour, as Mahar married a local queen/ or princess, allied himself with all the other tribes that were fighting the Romans and marched over the mountain road from Alacium to Aleria. The romans were outnumbered by this Carthaginian/Corsican army and forced to evacuate the city -army and roman settlers and traders alike- if they wished to survive the fall of Corsica. Mahar was now called Mahar the Skilled and resided in the freshly conquered city of Aleria, where he and his Corsican allies plundered the Roman treasures, goods and weapon depots and split them fair. To Romans and Carthaginians alike Mahar would later be known as the man that united the Punics and Corses as a unified tribe on Corsica and as the first fair and just ruler of the whole Island in it's history. Corsica under Mahar would later become part of an autonomous confederate province within the administration of the Isles in the Mediterranean between Italy and Africa.

(current world map)

Last edited: